Overview

When a salesperson is asked about their product or service, it is often seen less about truly understanding the product, rather an opportunity to recall and recite product facts. Knowing the load weight of a commercial vehicle or the internal cubic volume of a fridge may be useful to the conversation as pieces of factual content, but they hardly smack of detailed product knowledge when applied to the customer and their needs, when applied to the market and its needs, and when applied to future customers and future markets.

A chapter on the product or service, therefore, is not about the importance of learning by rote facts and figures but is instead about the importance of positioning the product against the competition, knowing where you sit and they sit, know where to go next, where to pursue, and where not to engage.

In this chapter, we will look at the product as it is today and what the potential is for the future. How to understand the market changes that impact on a product and how to react to them, or better still how to make them work in your favor. Simply knowing the product of today and the direction a company wants to take it requires a structured approach. When this direction is taking on a new competitor, it matters to understand how the customer sees your product, not just how the marketing team wants to position it. The largest companies and the smallest businesses are all prone to failure.

In September 2013, Microsoft acquired Nokia. At the press conference to announce the $7.17 billion takeover Nokia then CEO Stephen Elop announced “We didn’t do anything wrong, but somehow, we lost.” What Nokia did was simply not to understand the future direction of the market and the needs of the customer and not keep up with future trends and current needs.

International expansion, for any company, is fraught with danger. It can have a dramatic impact on the overall performance of the company and, on occasions, may even bring down a company. Cultural differences in the customer, buying behaviors and even the name all need to be understood. A market entry strategy defined only once the likelihood of success is known and seen as worth the risk. But that does not mean it is a slam dunk, and some great companies have found, to their cost, that a lack of preparation has dramatic consequences.

Knowledge About Your Product Not Product Knowledge

It might seem obvious that, at some point in the Sales Process, we should consider the product(s) or service(s) we are selling. Knowing what the best products and services are, which of these benefit the company the most and which add little value, financially or otherwise, is not always obvious and, for more than a few companies, something they fail to fully understand.

In 1957, the prototype “Orange Box” was produced and by 1959 went into production as the BMC Mini. In its day, a much-loved car. Unbelievably the car stayed in production until 2000. We are talking here about the 3-m long, 1.4-m wide box on wheels, not the modern, BMW variant. The car was a reaction to the changing demands because of the then current fuel crisis.

Prior to launch, BMC never realized what a huge success the car would go on to be. What makes the story of the Mini interesting is how Ford reacted. Aware that BMC was working on a new car and having seen it in the flesh some years before it went on sale, Ford too were working on upgrading a successful small family saloon and, in 1959 introduced the new Ford Anglia.

The Anglia had an oddly designed rear-raked rear screen and came pretty spartan, no glove box door, or passenger sun-visor; even the heater was extra. In bringing this to market, Ford realized they had a fight on their hands and so the price was a very keen £589 0s 11d—it matters nought if you cannot work out your Pounds, Shillings, and Pence. For every Anglia sold Ford made a loss.

What Ford saw with the Mini was a small saloon car trying to take some of their market. As a result, they shaved off some of the product features and set their price at a level that would sell, it was marginally more expensive than the Mini.

We can accept that in the 1950s the technology did not exist and the attention to detail on the supply chain did not allow them the level of cost detail we would expect today. However, instead of making the Anglia a higher value product, adding in heating, and so on (later they added a rear wiper at no cost!) and setting the price accordingly Ford decided to go against a car that, today, few people would agree they were direct market competitors.

Knowing your product or service, its value to your clients, the position you sit in the marketplace and the competition you are truly up against is key to any sale.

I was working for a client, a successful business, growing and profitable. However, despite several reviews and changes they had not achieved the profitability they felt they deserved. The company was, in all other respects, a great company.

The investigation we undertook pared every cost right back and broke apart the entire sales process. Every won deal and lost deal was measured, and costs applied. For fixed costs, these were even split differently based on the complexity of contracting or different regional requirements, even down to the time to draft special clauses. A weighty piece of analysis but with good reason.

The final report demonstrated that one sector they felt was successful, did indeed bring in a good level of income. But, because of the additional requirements, the more complex sales cycle and even local culture, the margin was considerably less than most other sales. Had this been a small part of their business the impact would have been less. Because it accounted for a significant part of their business, they were generating revenues that did little to add profit to the business.

To address this, my client simply changed their approach to this market. They played hard with new clients in the sector. They chased less deals and won less deals but the deals they won cost less to serve and had better margin. The time saved enabled them to focus on other sectors and even develop two new product offerings to another market.

The financial results showed a significant uplift and, with new products coming onstream the company ramped up its recruitment so they could sell even more of the good stuff.

It is important to understand what is really adding to the performance of the company and what is a successful sale that adds little incremental value. Being successful is not about winning more deals, it is about winning more of the right kind of deals.

Understanding the products and services you sell is not about reading the fact sheets or knowing what the Unique Selling Points (USPs) are. It encompasses the market fit, the competition, what is the best use of resources, be that financial or human resource.

Being able to identify the best product to lead with, it may even be loss-making. Knowing what the best cross-sell or upsell is, for the supplier and for the customer. Recognizing that not all products should be sold in all markets and that pricing may vary from one to another—and how to manage that when a client points it out.

Knowing when to launch a product, and when to pull one is also a part of understanding your product strategy. Knowing what product comes next in the sale to an existing client; and knowing when to enter new markets and which product to lead with. All these are elements required to understand your product. Knowing your product is not about what you sell today to whom, but what you can sell tomorrow as well and to whom else.

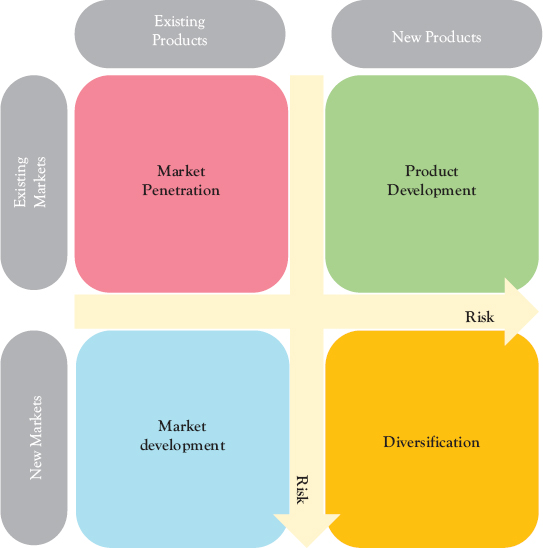

Figure 2.1 The Ansoff Matrix (Ansoff 1957)

In 1957, Russian-born, now U.S. citizen Igor Ansoff’s article in the Harvard Business Review entitled “Strategies for Diversification” developed what we now know as the Ansoff Matrix (see above, Figure 2.1). It focused on four areas: market penetration, market development, product development, and diversification.

Existing Products in Existing Markets

Developing your existing market from your existing product range is the lowest risk and, very often, least rewarding way to grow a business. This is less about product development more about market share and, sometimes, a greater market share does not mean greater profits and rarely means improved profit margins.

Sales is simply about selling more stuff. It does not have to be the same stuff or indeed to the same people. But to sell more stuff, you need to find new buyers and, in an existing market that requires one, or more, of the following:

• Price decrease

• Increase in promotion, advertising, and marketing

• Improved distribution capabilities/ability to serve

• Acquisition of a product/service rival in the same market

• Small product refinements/enhancements/development

Some of these will deliver greater results; numbers of units sold, revenues, or profits. To understand what will work the best and what will deliver what you wish may require some market testing.

It may well be that you serve one market well but not all the market segments. Whether that constitutes new markets or existing markets is an opinion often hotly debated between the sales team and the marketing team. But making sure you have achieved what you can from the market means reviewing the market segments first. Segmentation can come in many forms, but the standard approaches are as follows:

• Geographic

• Cultural

• Sociodemographic

• Behavioral

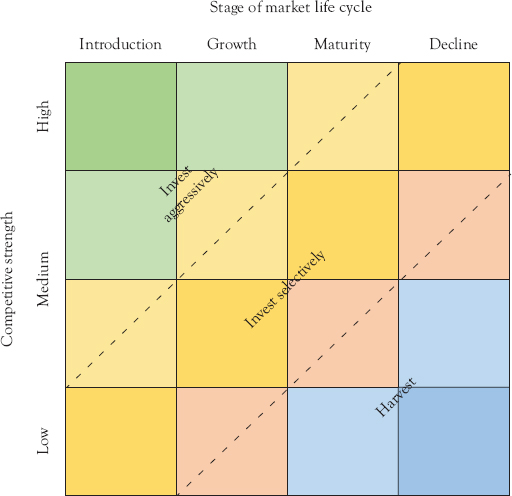

We should step away from the Ansoff Matrix at this point and look at the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) Matrix, Figure 2.2.

Occasionally referred to as the Growth-Share Matrix, it was developed by BCG Founder Bruce Henderson in 1968 to help companies focus their production lines and marketing on their most profitable products. As a tool the BCG Matrix is quite a blunt instrument and, for that reason, better serves when working with other tools.

The BCG Matrix considers only the current market and current products. Accepted that is its purpose but, it does so without consideration for cashflow, limits of production capacity or scarce resources, supply chain limits, and total demand for products or services.

BCG lacks an understanding of seasonality and of short-term spikes in demand. A Cash Cow may seem a good thing for income but there could be other products developed that, over time, become more profitable but do not get the resource needed because the focus is on serving the current cash generator.

Figure 2.2 The BCG Matrix

Cash Cows are there to be “milked” as they are, they are not really going anywhere unless others are willing to invest in winning business in a static market. Income generated from Cash Cows gives companies the opportunity to invest in new products or new markets for further growth. Despite the term “cash” net margin makes better sense than income. Generally, Cash Cows should not gain significant additional investment other than to keep them current or to maintain market share.

Where a company has a low market share compared to competitors and operates in a slowly growing market it can be a Dog. While general thinking is that they are not worth investing in, a view of potential future market growth should always be taken, not just current market position. What is a Dog today may become A Question-Mark tomorrow. For Dogs, it is always important to perform deeper analysis of each market to make sure they are not worth investing in for future potential.

High growth markets where companies have a low market share are something that requires better understanding of the future potential and whether to pursue. Question-Marks are the products that require closest attention as they could be the Stars of the future. Often referred to as a Problem Child, these markets can very often consume large amounts of investment incurring losses, at least in the short, or short-to-medium term. Not every Question-Mark pays off and knowing when to quit is a difficult decision to make.

In recent years, we have seen companies such as WeWork, Uber, Snap, AirBnB, Deliveroo, Pinterest, Slack, and many more, continually lose eye-watering sums of money. For investors this is a long play and for many will one day hopefully turn a profit. Question-Marks and Problem Child have never been more apt.

A Question-Mark has the potential to gain market share and become a star, which would later, perhaps, become a cash cow. Question-Marks do not always succeed and even after large amount of investments they struggle to gain market share and eventually become dogs. Therefore, they require very close consideration to decide if they are worth investing in or not.

Stars, as well as generating good income they also demand investment to maintain share and profits. It is important here to understand two things for a Star market. The cost required to maintain market share and the investment required to grow market share. Some star markets can be extremely demanding financially.

In rapidly changing industries, where innovation is key to stay at the forefront and where new products and technology can quickly change the market it is vital to keep investing. Investment can be in research and/or development (R&D), marketing, acquisition of competitors or suppliers, and changes to your market approach. To remain a Star, it can require consistent and significant investment as a result.

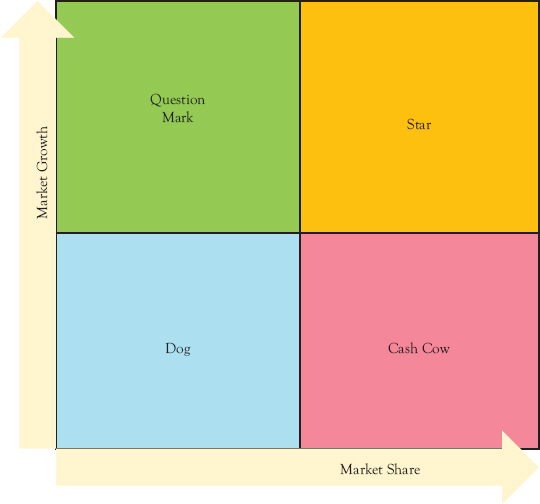

The BCG Matrix has been used as a basis for other models. Originally called the General Electric Multifactorial Analysis, later the GE-McKinsey Matrix (Figure 2.3), offers a slightly more complex view of product or service strength set against attractiveness to invest in a market. It follows many of the same principles but is more nuanced and gives a more detailed assessment of options.

Both these matrixes are a place to start rather than a final assessment of what course to follow. A decision on the course of action should be based on detailed analysis of the market today and future potential, the demand and what is required for future product development. It should also be something reviewed periodically to understand what has changed and the impact thereof.

Figure 2.3 The GE-McKinsey matrix

Taking a forward-looking view, the Life Cycle-Competitive Strength Matrix (see Figure 2.4) analyses the competitive strength of your product offering against the maturity of the product itself. Almost all products have a life cycle, whether it is the latest technology, restaurants, cars, even houses. True the house may still be standing when we sell it but as life changes and family demands change the individual demand for that specific product changes. Few items have a never-ending life cycle, typically this would only be staple foods such as bread, rice, and so on.

Starbucks opened its first store in 1971. It was not until 1988 that it opened its first store outside Seattle. That’s a very slow start to what is a huge company today. Rovio Entertainment Oyj developed 51 games before it developed Angry Birds.

Figure 2.4 The Life Cycle-Competitive Strength Matrix

The stage of the product life cycle is another indicator that can be used to make investment decisions, whether that is investment in the market to grow the business or market share or investment in the product to retain or gain new customers.

For most products, the maturity curve is shortening. Typically, a product will go through four stages: Introduction, Growth, Maturity, and Decline. Introduction for start-ups is proving more difficult and the number of failures at this stage is increasing. Once growth is reached very often the need to innovate and develop to maintain at the top becomes more demanding as product life cycles shorten.

Moving away from Existing Products in Existing Markets, we can focus on the other three portions of the Ansoff Matrix.

Market Development

Taking an existing product to a new market may not seem the most high-risk approach to growing your product sales but a lack of local knowledge can cost you dearly as Starbucks found out when they launched in Australia. They are not the only big company to get it wrong.

Tesco is a dominant player in the UK supermarket sector with over 7,000 stores worldwide and revenues, in 2019, of £63.9 billion. In 2007, Tesco launched into the United States. Timing was bad just before the 2008 financial crisis but, with the deep pockets Tesco had, they can afford to weather the storm. Unlike their competitors, Tesco did not see the value in coupons and had no loyalty card, well not until their last year of trading in the United States. In hard times, coupons become a required element for the shopper, certainly much more so in the United States than in Europe. Something Tesco failed to understand.

The Tesco, Fresh and Easy stores were more local than the big supermarkets. Suited to European shoppers, but not what the American shopper is used to and not what the American shopper wants in the main from a supermarket. There are several other errors Tesco made, self-checkouts, own-brand, low population density states, and so on.

In 2012, five years after launching, Tesco quit the United States. selling 150 of its approximately 200 stores. Tesco racked up losses of $1.6 billion for their troubles. Proof that if a company this big and successful can get it wrong, then anyone can. Size is no guarantee of success.

Before entering a new market, research is needed. Research what the customer wants and what the competition offers. Make sure you have a product that will sell and a way to sell it that will appeal. Entering a new market may be low risk but that does not mean it is no risk.

As well as new territories, new markets may include new market segments. Some may argue that it is the same market, but we will come back to that at the end.

CAGE Distance Framework

In 2011, Professor Pankaj Ghemawat, developed the CAGE Distance Framework, made up of Cultural, Administrative, Geographic, and Economic Distances to be measured Unilaterally, Bilaterally, and Multilaterally. Figure 2.5, gives a more detailed graphical representation.

To undertake a CAGE Distance, assessment can require a considerable amount of work and requires much local knowledge. Companies, some quite large, have either failed to do this well or have not used it effectively before embarking on an international expansion. For most of us, however, it may be a useful thing to know perhaps more than something used with definite intent.

Figure 2.5 CAGE Distance Framework

Cultural refers to language, beliefs, cultural norms, social hierarchy, and framework, religious, and attitudes toward both domestic and international matters. In the Tesco example previously, the cultural requirements of shoppers in the United States and their commitment to vouchers, the location of stores and shopping preferences would, or should, have all been identified had the company conducted a thorough assessment using the CAGE Distance Framework. Despite the fact the UK and United States share a common language and have many cultural similarities that does not guarantee all other cultural alignments remain the same.

Administrative differences consider not just governmental and political but historical norms, such as the past relationship between the two countries, especially relevant in countries with colonial ties. Beyond that it also refers to complexity of trading including currencies, tax, and law.

Of course, Geographical Distance is often a part to play in international expansion. However, think not only of distance but also topographical features, climate, border issues, and the ability to serve the new market not just reach it. Consideration should be given to the internal geography and supply chain requirements.

Finally, the Economic Distance between the two markets such as the cost of doing business as well as the affordability of your product in the new market.

All of this is set against Bilateral and Unilateral considerations. Consider how the two markets (countries perhaps) compare. How they trade between, and that the relationship is between the two. For Unilateral, how the new market stands not regarding your current market or point of origin.

Anyone who has travelled internationally can readily recall things that had novelty appeal and those that would never work back in their own country. Enjoying a German Bratwurst in many Western countries perhaps has greater appeal than a curried donut from Japan or chickens’ feet from China. Similarly, pickled herring has more appeal in Scandinavia and central Europe than the Middle East and south Asia. For companies looking to expand it is not enough to simply have a general understanding it requires a structured approach and detailed understanding. It relates also not just to retail but it is perhaps, where it comes into sharpest focus just how important it is to get right.

The pandemic that started in 2020 had a dramatic impact on the automotive industry. Sales of cars disappeared overnight as retailers were forced to close the supply chain as well as production and assembly plants were impacted by labor issues. Since 2021, it has allowed motor manufacturers to review their models and their markets. Holden, part of GM, retired from Australia and New Zealand, Mitsubishi announced it was “pulling back,” from North America and left Europe altogether; Renault and Nissan agreed to divide up their respective markets rather than compete. Other companies took similar approaches to certain markets or certain products. All these decisions were based on market share, product rationalization, future potential, cost, and return. However, not all automotive decisions are thus.

In 2007, Suzuki entered the North American automotive (car) market. They were already well established there through their motorcycles and, as Japan’s then fourth largest car manufacturer they had not only the financial muscle to edge their way in and survive but they also had a highly regarded brand and knew the territory. While it may be true that North American tastes and Japanese tastes in motor cars are different, that is much less the case today than in 1962 when GM produced 51 percent of all cars sold in the United States.

Honda entered the U.S. market in 1959 and by 2007 had revenues of $99 million. Suzuki accepted it would take a while to break into North America, but they believed they had a good start and, in the XL7 a good car that would appeal to their new target market. The company did its homework and believed it had a product that fitted the needs of the buyer and knew much about the buyer (Cultural).

Suzuki until 2006 had a partnership with GM and had established an assembly plant in Canada for their new vehicle. Through their motorcycle division they knew the market well and combined they therefore believed they could manage the Administrative challenges that awaited them.

Geography was not an issue for Suzuki as they had a plant in the territory and much experience of managing complex supply chains and distribution channels—online, direct, and through dealerships. In addition, there was no issue with the Economic distance as they were already established in North America.

Toyota was selling around 100,000 Highlanders per annum in North America at the time Suzuki entered the market. It looked like an ideal market for a GM-based product with some unique features (e.g., a third row of seats) and from an established brand. Total sales in 2007 and 2008 were 22,761 and 22,548, respectively. In 2009, Suzuki declared it was leaving the market.

Despite Suzuki ticking all the boxes for a CAGE assessment, it lacked the one thing that this did not cover. The Suzuki XL7 was a good product but was not a standout product able to take on established products in a competitive market. Even when you do have a great product, it still does not guarantee success.

It need not be complex products that fail. Certain products and services are ubiquitous around the world, from waiting and hospitality to travel and transport. But, of all products and services perhaps the ones that are seen most globally are some basic staple foods and beverages. So, in July 2000 when Starbucks opened its first shop in Australia, it did not seem such a big leap.

Starbucks assessed that coffee is drunk everywhere and, aside for personal preferences and sourcing the right mix of key ingredients, it is a relatively simple concept and a simple brew. For Starbucks, Australia represented a more local expansion than some of its already international offerings and even the language and culture were very similar.

Australia offered one of the biggest markets for coffee in the world and one would think an organization such as Starbucks would be professional enough to really do its homework, understand the market, identify buying habits, cultural differences, flavors, and wants of the customers and, potentially, buy a local coffee shop or two and learn from them. Sadly, for Starbucks, although perhaps not the consumers, they simply looked at Australia as similar to the United States and, because of much of its recent heritage, Europe. It followed that copying what they had done before would simply work.

By late 2007, Starbucks had amassed 87 stores across Australia. Their financial muscle helped accelerate their expansion across this vast country and, with deep pockets they could weather the short-term financial losses. In the first seven years, these losses were estimated to be US$54 million.

What Starbucks missed was that Australians prefer independent, local chains. Also, Starbucks also was more expensive than small cafes. Eight years after it entered the market, Starbuck eventually gave up and closed 61 stores. That they stayed eight years is remarkable. Some years later, in 2014, Starbucks eventually learnt to adapt rather than admit defeat completely. Their last remaining outlets were handed over to Withers Group which, until 2019 owned 7-Eleven in Australia. Accounts for 2020 show that Starbucks is still losing money in Australia.

When Starbucks entered China, it invested heavily in understanding Chinese family values and cultural norms of their new market. It tailored its offering not just the beverages but also how it managed its staff (“partners”) and treated its customers. Knowing China was going to be different ensured Starbucks fully investigated and understood. Thinking Australia was the same as Europe and North America meant a lot less due diligence was done.

Not understanding the Environment into which you are going can be costly, and if Starbucks can get it wrong then so can anyone.

CAGE could be applied regionally as well as internationally. In countries as large as the United States, Russia, China, and India, there can be significant differences in many elements from one region or state to another. Indeed, even climate can have an impact, so it could be you want to apply the CAGE Distance Framework to not just international expansion.

Creating new products and services to appeal to the existing market or client base is an effective way to expand the product portfolio. The challenge often is finding the right product that complements the existing product and does not cannibalize the existing revenue streams.

The most obvious way to achieve this is to develop new products or services but this requires research and development and does not guarantee success. Acquisition of rights to produce another company’s products or to secure rights to sell in your region or territory is a way to acquire a new product without the R&D. However, as we have seen, the success of a product or service in one market does not guarantee the same in another.

Of course, buying a competitor that has a broader product range or buying a company that has a divergent range but one that sits well in your market could also prove beneficial.

Apple went from developing desktop computers to laptops, phones, personal devices, wearables, and much more. Away from the hardware side, they have developed significant revenue streams in application downloads and music streaming services. By evolving the brand and by adding products incrementally that have created a loyal customer base eager for the next product.

Diversification

We have mentioned taking an existing product to a new market or tasking a new product to the existing market. But taking a new product to a new market is extremely high risk and rarely done. It has succeeded but rarely.

The Colgate brand is well known, the true pioneers of toothpaste. In 1982, Colgate Palmolive, under the Colgate brand, introduced frozen ready meals. Perhaps they were trying to stimulate demand for their main product! Of course, it did not work.

Where the brand name is powerful it can work. Virgin Group has diversified into many different products and services appealing to different markets. In the UK Tesco, a food retailer, branched out into various financial services, mobile phones and is always looking to diversify further.

Brand value and customer loyalty can help significantly when companies develop new product offerings. For most companies, there is only a certain amount of brand stretch. Had Tesco offered banking services in the 1960s it would most likely have failed, who would trust a grocery store with their savings and investments?

Understanding what is possible in terms of stretching your customers to buy new products or services requires an understanding of your clients and the way they buy and what else they may be willing to buy.

A client of mine had run a successful commercial cleaning and maintenance company. It had grown over several years and had achieved great success in a large part of the UK. It had acquired competitors either to remove the competition or to grow their client list and order-book. However, the next step was more challenging.

To continue in their chosen field and expand further geographically would pose a logistical challenge for them and their in-house supply chain as well as push their flexible part-time and contingent workforce even farther afield.

We proposed they buy several small, local office supply companies. This would complement their product offering and not challenge their geographical scope. They were already used to dealing with the buying departments of their clients and had several regional and local governmental organizations as well as multiple medium-sized commercial businesses. This approach would allow them to grow their revenues and profits, whilst not challenging their regional structure. It would strengthen their existing relationship with their buyers too.

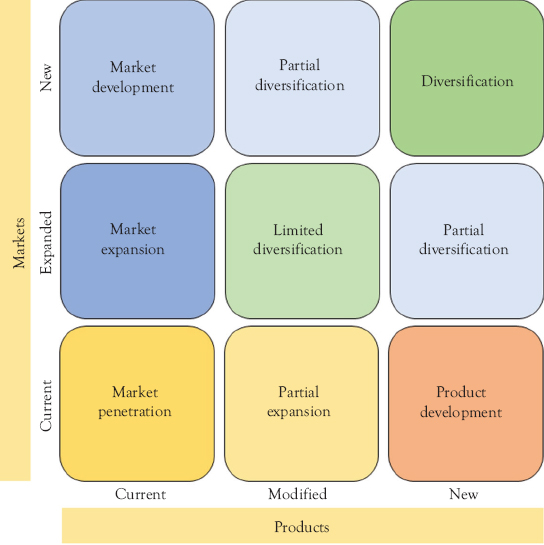

The Ansoff Matrix is a relatively simple model that, perhaps, does not suit well the complex businesses of today. As a result, you may see a developed version of the Matrix where it is not simply a 2×2 matrix of yes or no but something with a more granular view of the options open to a company. An example of this is the Expansion and Diversification market strategies matrix, as demonstrated in Figure 2.6.

It is not uncommon that companies do not fully understand their product or service. It is also not uncommon for companies to undertake multiple market or product expansions/developments at the same time. Equally not every foray ends in failure, but it is true that success is better achieved if you really understand your product and where you can take it, what you can do with it next.

Figure 2.6 Expansion and Diversification market strategies

Cross-Sell and Upsell

Cross-selling and upselling are as much about sales ability as product and product development. Neither of them fit well in the Ansoff Matrix but it would be remiss to leave them both out.

Cross-selling is when one product leads to another that is related and can be sold alongside. Upselling is when a better product is sold in replacement of the one the customer opted for first. It is an often-argued point whether Upselling and Cross-selling fit into Product Development or are outside the Ansoff Matrix. To my mind if you sell something in addition that is clearly Product more than Market development and if Upselling then it is the same product to some degree just with a higher ticket price or better margin, or both.

Salespeople should be targeted on their Upsell and Cross-sell performance specifically, not just on new name business or account retention. Accepted it may not always be easier, or indeed always possible, but to ignore these two vital opportunities is to ignore the potential for improved sales performance.

How you target salespeople on Cross-sell and Upsell really depends on the product and services you sell.

Cross-sell may not happen immediately. As people moved to working from home more consistently in 2020, the demand for bigger monitors and laptops sharply increased. But this was long after the initial surge of demand for laptops and basic peripherals. The demand for additional equipment and even larger monitors maintained and other peripherals such as better audio recording and playback equipment continued to grow. Companies in the hardware supply industry focused first on satisfying the demand for new homeworkers and then began following up later, once people were established at home, to sell bigger and better hardware. The year 2020 began as a huge opportunity for new hardware and ended with a huge opportunity for Upsell and Cross-sell.

Key Takeaways

Product knowledge is a key part of any salesperson’s arsenal. Not so much the detailed facts and figures rather how it benefits the end customer, how it compares the competition, and what USPs it brings to the conversation. Understanding the product or service allows the salesperson to elevate their offering above the rest. It allows the customer to make the decision in favor of our salesperson and it ensures that any later scrutiny supports the initial decision.

In the world of complex sales, marketing teams will spend considerable amounts of time developing competitor analysis reports. Often in the form of a simple chart to compare ours to theirs. Typically, these would be one per (major) competitor and perhaps a general report for the lesser competitors. Whether a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) Analysis or other should not matter if it serves the purpose of helping the salesperson present their product in an advantageous light.

Product knowledge is not just about the product or service as an island, as we have seen, but how it fits into the current market and whether it serves the needs and demands of the customer. Merely having the best product and significant market share is not sufficient. Understanding where the market is going and what the future looks like for the customer and for our product, and how these two align is important.

Understanding what differences there are between the market we serve today and where the customer wants to take it tomorrow also matter. Simply selling a solution in one territory or country that is ill-suited to another needs to be managed, either in how the solution is sold or in the future product roadmap. Tools such as Ansoff, BCG, and GE-McKinsey help us identify the state now as a potential strategy for tomorrow.

To know where the customer is heading and what they want from the future and being able to address that requires a detailed understanding of the product and the future of the product. The CAGE Distance Framework examples we have provided were international, but it can be easily applied to regional and even local markets.

Knowing product strengths and that of the competition are important. Knowing the future direction and potential of a competitor can be a hard question to answer. It matters that salespeople feedback what they learn and understand to their sales colleagues and to marketing to build a picture not just of the competitive landscape today but also of tomorrow. It also matters that the company uses simple tools to gather feedback and formulate an understanding and always stay one step ahead of the market.

Great salespeople spend time not to learn their product but to understand their product. They spend time understanding the competition and they invest in understanding the customer. They know not only what the customer wants but what the customer wants next or how to sell more. Where all these combine is where great salespeople shine and where deals are made bigger or are won and lost. It is not just enough to merely know your product anymore.

Sales Opportunity Management is a step-by-step approach moving from the first conversation through to sales success. It is a structured and disciplined approach led by the salesperson. Without a good understanding of our product strengths and weaknesses and that of the competition, and without an understanding of the needs of the customer and the market means even the best management of a sales pursuit will fail. Sales Opportunity Management cannot operate effectively as a standalone process, detached from the customer needs.