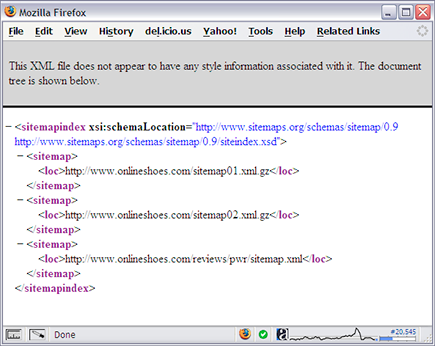

Figure 12-1: A small XML sitemap.

Chapter 12

Getting Your Pages into the Search Engines

In This Chapter

![]() Submitting your pages to the search engines

Submitting your pages to the search engines

![]() Creating, submitting, and pinging sitemaps

Creating, submitting, and pinging sitemaps

![]() Submitting to secondary search engines

Submitting to secondary search engines

![]() Using registration services and software

Using registration services and software

You built your Web pages. Now, how do you get them into the search systems? That’s what this chapter and Chapter 13 explain. In this chapter, I talk about how to get your pages into search engines, and in Chapter 13, I explain how to list your site with search directories.

Search engines can find out about and index your site in essentially three ways:

![]() Links pointing to your site

Links pointing to your site

![]() Simple link-submission pages

Simple link-submission pages

![]() Sitemap submissions

Sitemap submissions

The most important of these is the first — links pointing to your site lead the search engine to it. The second is worthless. And the third is very important and comes with a number of ancillary benefits. In this chapter, I tell you about these strategies one by one.

Linking Your Site for Inclusion

In Chapters 15 through 17, I talk about the importance of — and how to get — links pointing from other sites to yours. The more links you have pointing at your site, the more important the search engines will think your pages are.

Links are also important because they provide a way for search engines to find your site. Without links, you might get your site into search engine indexes, but chances are, you won’t. And being included in the most important index — Google’s — is much quicker through linking than through registration. I’ve had sites picked up and indexed by Google within two or three days of having put up a link on another site. If you simply submit your URL to Google (the next method I look at), you may have to wait weeks for it to index your site (if it ever does).

But one or two links sometimes aren’t enough for some search engines. They often are for Google: If it sees a link to your site on another site that it’s already indexing, it will probably visit your site and index it, too. But other systems are far choosier and may not visit your site even if they do see a link to it. So the more links you have pointing to your site, the better. Eventually, search engines will get sick of tripping over links to your site and come see what the fuss is all about.

Simple Link Submissions to the Major Systems

The top two search engines — Google and Bing — provide a very simple way for you to tell them where your site is. Submit your site for free on these pages:

![]() Google:

Google: https://www.google.com/webmasters/tools/submit-url

![]() Bing:

Bing: https://ssl.bing.com/webmaster/SubmitSitePage.aspx (scroll to the bottom of this page)

Google actually provides a similar method, from within the Google Webmaster account (which I talk about in the next section). The Webmaster account has a Fetch as Googlebot tool (under the Diagnostics menu). You can use this tool to have Google pull a page and show you the code it has crawled. You can then click the Submit to Index link to submit that page to the Google index. Still, it doesn’t guarantee that Google will index the page you submit, though it might be worth trying if you have some particular pages on your site that you can’t seem to get indexed.

How about Ask.com? It offers no way to submit your Web site. It relies on its searchbots to find pages through links.

However, now that I’ve given you these links for submitting your site’s pages, let me say one more thing: Don’t bother.

Using these submission pages is unnecessary and may not even work. As Google says, “We do not add all submitted URLs to our index, and we cannot make any predictions or guarantees about when or if they will appear.”

Bing is a little more positive, perhaps, but still offers no guarantee: “This change will not be reflected immediately, so please be patient and check back periodically.”

I don’t bother submitting URLs to search engines using these simple URL submission pages. But I want you to be aware of them because these submissions are one of the biggest scams in the history of SEO (a business that is rife with scams). Hundreds of submission services convinced many thousands of Web site owners to pay to have their sites submitted to the search engines, often repeatedly. It was a totally pointless waste of money.

You don’t need to use basic URL submission. You need links to your site, and you should submit a sitemap, which I cover next.

Submitting an XML Sitemap

I do recommend one form of site submission. It isn’t a replacement for pointing links to your site, but it can, in some cases, improve indexing of your site. I’m talking about creating XML sitemaps, submitting them to Google and Bing, and making it easy for other search engines, such as Ask.com, to find the sitemap on their own.

In 2005, Google introduced a new submission system and was soon followed by Yahoo! and Bing (and now, of course, Yahoo! and Bing have partnered, so they act as one system). In Chapter 7, I recommend creating an HTML sitemap page on your site and linking to it from the home page. The sitemap is a page that visitors can see and that any search engine can use to find its way through your site.

But an XML sitemap is different: It’s a special file placed on your site that contains an index to help search engines find their way to your pages. You create and place the file and then let the search engine know where it is. This hidden file (visitors never see it) is in a format designed for search engines. I think it’s worth your time to create this file because doing so is not a huge task and may help, particularly if your site is large. Also, after you’ve submitted a sitemap and “verified” your submission, the search engines give you lots of interesting information about your site.

In Google’s words, “Using sitemaps to inform and direct our crawlers, we hope to expand our coverage of the Web and speed up the discovery and addition of pages to our index.” If I can help Google by getting it to index my site more quickly, well, that’s fine by me.

What does this sitemap file look like? Take a look at Figure 12-1.

Don’t worry: XML sitemaps are easy to create; I show you how in the next section.

These sitemaps are typically named sitemap.xml (though different names can be used) and placed into the root directory of the Web site — in the same directory as the home page.

Creating your sitemap

You can create a sitemaps file in various ways. Google provides the Sitemap Generator program (code.google.com/p/googlesitemapgenerator/), which you can install on your Web server; it’s a Python script, so if you don’t know what that means and don’t have a geek who does, consider creating the file another way.

If you’re the proud owner of a large, sophisticated, database-driven site, it’s probably a job for your programmers; they should create a script that automatically builds the XML sitemap.

What if you own a small site, though, and have limited technical skills? No problem: Plenty of free and low-cost sitemap-creation tools are available.

Note that many of the tools call themselves Google sitemap creators, because Google was the first search engine to use sitemaps. All you need, however, is the basic Google XML sitemap format for all the other search engines, so if it creates a “Google” sitemap, it will work fine.

Some of these programs run on your computer, some require installing on your Web server, and some are services run from another Web site. You can find a large list of these sitemap generators here:

code.google.com/p/sitemap-generators/

My favorite sitemap generator for small sites is XML-Sitemaps.com. You simply enter your domain name into a Web page, and it spiders your site, creating the sitemap as it goes, up to 500 pages. If your site is bigger, you can get the service to install a script on your Web server for $20 (assuming that your server can run PHP scripts).

Submitting your sitemaps

You can tell search engines about your sitemaps in three different ways:

![]() Submit a sitemap through the search engine’s Webmaster account.

Submit a sitemap through the search engine’s Webmaster account.

![]() Include a line in the

Include a line in the robots.txt file telling a search engine where the file is.

![]() Ping the search engines.

Ping the search engines.

The last method is pretty much optional. You should definitely submit your sitemap to Google and Bing and use a robots.txt file.

Submitting using the Webmaster account

You should set up an account on both the major systems (Google, and Bing; Ask.com doesn’t currently have Webmaster accounts) and submit your Web site’s XML sitemap. Then review the various tools that are available. Here’s where you can find the Webmaster areas and sitemap-submission pages for the three top systems:

![]() Google:

Google: www.google.com/webmasters

![]() Bing:

Bing: www.bing.com/webmaster

However, in some cases, Web site owners don’t want search engines to know that their sites are associated; for instance, if a site owner has three sites, all of which rank on the first page for important keywords, he may not want it to be obvious that all sites are owned by the same person. In such a case, of course, the owner would set up separate accounts for submitting each sitemap.

Here’s the basic process you use at all these services:

1. Set up an account.

In each case, you have to set up a password-protected account.

2. Add the URL of your Web site.

3. Tell the search engine where the sitemap is.

You provide the URL that points to your sitemap; the search engine checks to see whether it can find the file.

4. Verify your site.

You can verify your site in several ways:

• You can choose to get a verification file, a small text file, that’s stored on your server. For instance, Google provides you with an .html file that you can download and place in your site. The file contains a single line of text, something like this: google-site-verification: googlec4b99698d01b26f2.html.

• You may use a special meta tag that you add to your home page (something like <meta name=”google-site-verification” content=”1bkH4kUFdeKgcMhxOj8e06-7faFDZqAnS2jvGUDITRg” />).

• You can choose to add a record — a snippet of information — to your domain name’s DNS information. Don’t try this unless you’re sure you know what you are doing.

• Google Webmaster also allows you to verify your site by associating it with your Google Analytics account (see Chapter 24).

5. Tell the search engine that the file or meta tag has been added to your site, that you’ve changed your DNS record, or (in the case of Google) tell it that you have a Google Analytics account, and ask it to “verify” the file.

The search engine then checks to see whether the file, meta tag, or DNS record is present (or Google checks to see whether your site contains the correct Google Analytics code). If the search engine finds what it’s expecting, it assumes that you must own or have control over the specified site, and thus is willing to provide you with more information about the site.

Each system is different, so I can’t go into detail about how each works. Spend a little time digging around and you’ll soon figure it out. Remember, the basic process is to add your site URL, add your sitemap URL, and then verify or authenticate.

Using the robots.txt file

You need a robots.txt file in the root directory of your Web site, with the following line inside it:

Sitemap: http://www.yourdomain.com/sitemap.xml

The URL should point to your sitemap, of course. The URL tells the search engines that don’t provide a Webmaster account — such as Ask.com — where your sitemap is, so you’ll want to do this even though you’re submitting your site through the Google and Bing Webmaster account.

Pinging search engines

Pinging a search engine means sending a message to the search engine telling it where a sitemap is, and telling it that the sitemap has changed. As of this writing, you could ping all three of the major systems — Google, Bing, and Ask.com — and some smaller systems, such as didile.com (for your Turkish Web sites).

You can see this process in action for yourself. Create a sitemap and then change the following URL to show the path to your sitemap:

http://www.google.com/ping?sitemap

Copy and paste this URL into a browser and press Enter, and you receive this response from Google:

Sitemap Notification Received

Your Sitemap has been successfully added to our list of Sitemaps to crawl. If this is the first time you are notifying Google about this Sitemap, please add it via http://www.google.com/webmasters/sitemaps so you can track its status. Please note that we do not add all submitted URLs to our index, and we cannot make any predictions or guarantees about when or if they will appear.

These are the sitemap-submission URLS; put the full URL to your sitemap, including http://, after the = sign:

http://www.google.com/ping?sitemap

http://www.google.com/webmasters/sitemaps/ping?sitemap

http://www.bing.com/webmaster/ping.aspx

http://submissions.ask.com/ping?sitemap

http://www.didikle.com/ping?sitemap

You can manually ping sites each time the search engine is updated. If you have a programmer build your sitemaps automatically by pulling data from a database, the programmer should add a ping function to ping the search engines each time the sitemap is updated. And, some sitemap-creation programs that you can buy have built-in ping functions; the version of the XML-Sitemaps.com program that you install on your server can automatically ping for you.

Using Webmaster tools, too

As the previous section notes, the two top search engines — Google, and Bing — now provide Webmaster accounts through which you can submit your sitemap and provide various tools related to your sitemaps. Some of these tools are available even if you don’t submit a sitemap, but if you do submit a sitemap and then prove that you are the owner of the site (through the authentication or verification process I mention earlier), you’ll be provided with more information.

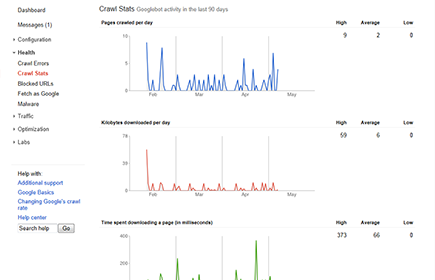

Right now, Google has the best tools and statistics associated with its Webmaster account (see Figure 12-2). Table 12-1 explains some of these tools.

Table 12-1 Google’s Webmaster Tools

|

Tool |

What It Does |

|

The Configuration Menu |

|

|

Settings |

Tells Google that you’re most interested in searchers in a particular country; that you want Google to assume that |

|

Sitelinks |

Lets you tell Google not to use particular pages as Sitelink pages (discussed in Chapter 24). |

|

URL Parameters |

Lets you tell Google to ignore certain URL parameters. |

|

Change of Address |

Allows you to redirect one domain to another, telling Google that, for instance, you’re using a new domain name. |

|

Users |

Allows you to provide access to your Webmaster account to other users. |

|

The Health Menu |

|

|

Crawl Errors |

Shows problems that Google found while crawling your site. |

|

Crawl Stats |

Information about how quickly and how often Google crawls your site (see Figure 12-2). |

|

Blocked URLs |

Lets you create and test a |

|

Fetch as Google |

Lets you get Googlebot to fetch a page from your site so you can see it how Googlebot sees it. |

|

Malware |

Information about malware on your site (which might happen if your site has been hacked). |

|

The Traffic Menu |

|

|

Search Queries |

Indicates which search queries most often returned pages from your site and which ones were clicked. |

|

Links to Your Site |

Shows links from other sites pointing to your site, indicates which page inside the site they point to, and what keywords are used in the links (an excellent tool!). |

|

Internal Links |

Shows links between pages within your site. |

|

The +1 Reports Submenu |

|

|

Search Impact |

The +1 button is a button that you can place onto your Web site to help visitors recommend your site (see Chapter 18). This menu option shows you the effect of using the +1 system — how many people arrive at your Web site through search after clicking on a +1 link. |

|

Activity |

Shows you how often people have clicked on your +1 button. |

|

Audience |

Show you who is clicking on your +1 buttons: how many people, where they are, their ages, and gender. |

|

The Optimization Menu |

|

|

Sitemaps |

This is where you test and submit a sitemap; Google will tell you when it processed it, if it found any errors, and how many pages it found within the sitemap. |

|

Remove URLs |

Lets you remove pages from the Google index. |

|

HTML Improvements |

Problems Google may have found on your site, such as duplicate, long, or short meta description tags, and missing, duplicate, long, short, or noninformative |

|

Content Keywords |

Keywords that Google found while crawling your site and believes are significant, giving you an idea of what Google thinks of your site. |

|

Other Resources |

Links to the Rich Snippets tool, Google Places, and the Google Merchant Center. |

|

The Labs Menu |

|

|

Custom Search |

Helps you create a custom search system for your Web site using Google to provide the search results (see www.google.com/cse). |

|

Instant Previews |

Shows you what the instant previews will look like (the pop-up preview of your site that appears in the search results when you click on the little >> button to the right of your listing in the search results). |

|

Site Performance |

Shows how quickly your site’s pages load. |

Figure 12-2: You can see how often Google crawls your site and how quickly pages download.

This is pretty nifty stuff, eh? Sitemaps are great for big sites; they can really help with indexing. But even if you have a small site, submitting and verifying a sitemap is a great way to get some very useful information about your site. (Actually, strictly speaking, you can create a Webmaster account for your site, verify the site, and then access this information even if you haven’t submitted a sitemap. However, if you’re going to all that trouble, you might as well spend a few minutes with a tool such as XML-Sitemaps.com and submit the sitemap as well.)

Submitting to Secondary Systems

You can also submit your site information to smaller systems with perhaps a few hundred million pages in their indexes — and sometimes far fewer. The disadvantage to these systems is that they’re seldom used, compared to the big systems discussed earlier in this chapter. Many search engine professionals ignore the smaller systems altogether. On the other hand, if your site is ranked in these systems, you have much less competition because they’re so small.

![]() ExactSeek:

ExactSeek: www.exactseek.com/add.html

![]() Gigablast:

Gigablast: www.gigablast.com/addurl

You can find more, including regional sites, listed on the following pages:

![]()

www.searchenginewatch.com/article/2067248/Guides-To-Search-Engines

![]()

http://dmoz.org/Computers/Internet/Searching/Search_Engines

![]() Programmable keyboard: You can assign a string of text — a URL, an e-mail address, and so on — to a single key. Then all you need to do, for instance, is press F11 to enter your e-mail address.

Programmable keyboard: You can assign a string of text — a URL, an e-mail address, and so on — to a single key. Then all you need to do, for instance, is press F11 to enter your e-mail address.

![]() Text-replacement utility: Replace a short string of text with something longer. To enter your e-mail address, for instance, you might type just em.

Text-replacement utility: Replace a short string of text with something longer. To enter your e-mail address, for instance, you might type just em.

Is it really worth submitting to these secondary search engines? As I mention in Chapter 1, somewhere around 95 percent of all search results are provided by the major search engines, so submitting to the secondary search systems may not be worth the trouble. I think it’s one of those “Well, I’ve got the time, so I might as well do it” kind of things.

Using Registration Services and Software Programs

You can also submit your pages to hundreds of search engines by using a submission service or program. Many free services are available, but some of them are outdated, running automatically for a number of years now and not having kept up with changes on the search engine scene.

Many free services are definitely on the lite side. They’re provided by companies that hope you’ll spring for a fee-based full service.

Some free services also combine links and directory registrations, along with search engine registrations. (I discuss directory registrations in Chapter 13.) By providing links pointing to your site, they can guarantee that your site will be picked up by the major search engines; it’s not the submissions to the search engines that are doing the work — it’s the links!

Note also that some submission services increase their submission counts by including all services that are fed by the systems they submit to. Some submission services inflate their numbers by including search engines that don’t even exist any more. In fact, I feel that some (many?) submission services are little more than scams, charging in some cases very high monthly fees for what’s really a service with relatively few benefits.

Still, if you want to try them, here are a couple of services (with more reasonable fees) that you might check out:

![]() AdPro:

AdPro: www.addpro.com

![]() ineedhits:

ineedhits: www.ineedhits.com

There are many, many submission services; search for search engine submission service, and you’ll find a gazillion of them.

A few submission software programs are available as well, such as Submit Wolf (www.trellian.com/swolf). The big advantage of these software programs is that you pay only once rather than pay every time you use a service.

You actually have a couple of reasons to use these automated tools. You may get a little traffic out of these small search engines, but don’t bank on getting much. In many cases, though, the systems being submitted to are not really search engines — they’re search directories, and being listed in a directory may mean that major search engines pick up a link pointing to your site. (Several of the systems listed by AddPro, for instance, are directories rather than search engines.) I talk more about submitting your site to search directories in Chapter 13, and you discover the power of linking in Chapters 15 through 17.

It’s all about links. The search engines believe that they can maintain the quality of their indexes by focusing on Web pages that have links pointing to them. If nobody points to your site, the reasoning goes, why would the engines want to index it? If nobody else thinks your site is important, why should the search engines? They would rather find your pages themselves than have you submit the pages.

It’s all about links. The search engines believe that they can maintain the quality of their indexes by focusing on Web pages that have links pointing to them. If nobody points to your site, the reasoning goes, why would the engines want to index it? If nobody else thinks your site is important, why should the search engines? They would rather find your pages themselves than have you submit the pages. You don’t need a separate account on each system for each Web site you own — you can submit multiple sites through each account, though the number of Web sites that you can manage through each account is limited (Bing limits the number of sites to 125 sitemaps; for Google, it’s around 400 . . . enough for most people!).

You don’t need a separate account on each system for each Web site you own — you can submit multiple sites through each account, though the number of Web sites that you can manage through each account is limited (Bing limits the number of sites to 125 sitemaps; for Google, it’s around 400 . . . enough for most people!). A few sites require that you submit your site with a username and password. Most sites require at least an e-mail address; some also require that you respond to a confirmation e-mail before they add your site to the list.

A few sites require that you submit your site with a username and password. Most sites require at least an e-mail address; some also require that you respond to a confirmation e-mail before they add your site to the list.