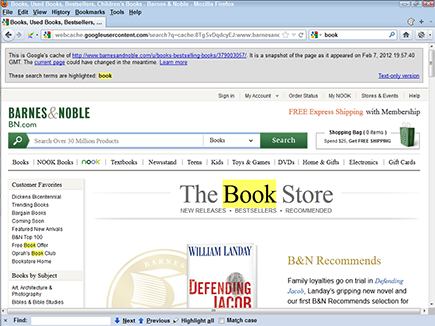

Figure 3-1: A page stored in the Google cache.

Chapter 3

Your One-Hour, Search Engine–Friendly Web Site Makeover

In This Chapter

![]() Finding your site in the search engines

Finding your site in the search engines

![]() Choosing keywords

Choosing keywords

![]() Examining your pages for problems

Examining your pages for problems

![]() Getting search engines to read and index your pages

Getting search engines to read and index your pages

A few small changes can make a big difference in your site’s position in the search engines. So instead of forcing you to read this entire book before you can get anything done, this chapter helps you identify problems with your site and, with a little luck, shows you how to make a significant difference through quick fixes.

It’s possible that you may not make significant progress in a single hour, as the chapter title promises. You may identify serious problems with your site that can’t be fixed quickly. Sorry, that’s life! The purpose of this chapter is to help you identify a few obvious problems and, perhaps, make some quick fixes with the goal of really getting something done.

Is Your Site Indexed?

It’s important to find out whether your site is actually in a search engine or directory. Your site doesn’t come up when someone searches at Google for rodent racing? Can’t find it in Bing? Have you ever thought that perhaps it simply isn’t there? In the next several sections, I explain how to find out whether your site is indexed in a few different systems.

I’ll start with the behemoth: Google. Here’s the quickest and easiest way to see what Google has in its index. Search Google, either at the site or through the Google toolbar (see Chapter 1) for the following:

site:domain.com

Don’t type the www. piece, just the domain name. For instance, say your site’s domain name is RodentRacing.com. You’d search for this:

site:rodentracing.com

Google returns a list of pages it’s found on your site; at the top, underneath the search box (or perhaps somewhere else; it moves around occasionally), you see something like this:

2 results (0.16) seconds

That’s it — quick and easy. You know how many pages Google has indexed on your site and can even see which pages.

Here’s another way to see what’s in the index — in this case, a particular page in your site. Use the following method if you’re using the Google toolbar (http://toolbar.google.com), available for Internet Explorer, Google Chrome, and some early versions of Firefox. Open your browser and load a page at your site. Then follow these steps:

1. Click the PageRank button on the Google toolbar.

A little drop-down menu appears.

2. Choose Cached Snapshot of Page from the drop-down list that appears.

If you’re lucky, Google loads a page showing you what it has in its cache, so you know Google has indexed the page (see Figure 3-1). If you’re unlucky, Google tells you that it has nothing in the cache for that page. That doesn’t necessarily mean that Google hasn’t indexed the page, though.

If you don’t have the Google toolbar, you can instead go to Google (www.google.com) and type the following into the Google search box:

cache:http://yourdomain.com/page.htm

Replace yourdomain.com with your actual domain name, and page.htm with the actual page name, of course. When you click Search, Google checks to see whether it has the page in its cache.

What if Google doesn’t have the page? Does that mean your page isn’t in Google? No, not necessarily. Google may not have gotten around to caching it. Sometimes Google grabs a little information from a page but not the entire page.

Yahoo! and Bing

And now, here’s a bonus. The search syntax I used to see what Google had in its index for RodentRacing.com — site:rodentracing.com — not only works on Google but also Yahoo! and Bing. That’s right, type the same thing into any of these search sites and you see how many pages on the Web site are in the index (though doing this at Yahoo!, of course, gets you the Bing results because they share the same index).

There’s one caveat: The results are a little flaky. For instance, it may initially show, say, 750 results, but as you move through the results pages, in either Yahoo! or Bing, you’ll see a different number — 546, perhaps. Sometimes that number increases, sometimes it decreases. Bing has been acting like this for years (and Yahoo! started doing the same when it began using Bing results), so it may — or may not — be fixed at some point. (Yes, Google has the same problem, but not as bad.)

Yahoo! Directory

You should check whether your site is listed in the Yahoo! Directory. You have to pay to get a commercial site into the Yahoo! Directory, so you may already know whether you’re listed there. Perhaps you work in a large company and suspect that another employee may have registered the site with Yahoo! Here’s how to find out:

1. Point your browser to http://dir.yahoo.com.

This takes you directly to the Yahoo! Directory search page.

2. Type your site’s domain name into the Search text box.

All you need is yourdomain.com, not http://www. or anything else.

3. Ensure that the Directory option button is selected and then click Search.

If your site is in the Yahoo! Directory, your site’s information appears on the results page. You may see several pages, one for each category in which the site has been placed (although in most cases, a site is placed into only one category).

Open Directory Project

You should also know whether your site is listed in the Open Directory Project (www.dmoz.org). This is a large directory of Web sites, actually owned by AOL although volunteer run; it’s important, because its data is “syndicated” to many different Web sites, providing you with many links back to your site. (You find out about the importance of links in Chapter 15.) If your site isn’t in the directory, it should be.

Just type the domain name, without the www. piece. If your site is in the index, the Open Directory Project will tell you. If it isn’t, you should try to list it; see Chapter 13.

Taking Action If You’re Not Listed

First, if your site isn’t in Yahoo! Directory or the Open Directory Project, you have to go to those systems and register your site. See Chapter 13 for information (including a discussion on whether it’s worth the $299 a month for Yahoo!). What if you search for your site in the search engines and can’t find it? If the site isn’t in Google or Bing, you have a huge problem.

Here are two possible reasons your site isn’t being indexed in the search engines:

![]() The search engines haven’t found your site yet. The solution is relatively easy, though you won’t get it done in an hour.

The search engines haven’t found your site yet. The solution is relatively easy, though you won’t get it done in an hour.

![]() The search engines have found your site but can’t index it. This is a serious problem, though in some cases you can fix it quickly.

The search engines have found your site but can’t index it. This is a serious problem, though in some cases you can fix it quickly.

For the lowdown on getting your pages indexed in search engines — to ensure that the search engines can find your site — see the section “Getting Your Site Indexed,” later in this chapter. To find out how to make your pages search engine–friendly — to ensure that when found, your site will be indexed well — check out the upcoming “Examining Your Pages” section. But first, let me tell you how to check whether your site can be indexed.

Is your site invisible?

Some Web sites are virtually invisible. A search engine might be able to find the site (by following a link, for instance). But when it gets to the site, it can’t read it or, perhaps, can read only parts of it. A client of mine, for instance (before he was a client), built a Web site that had only three visible pages; all the other pages, including those with product information, were invisible.

How does a Web site become invisible? I talk about this subject in more detail in Chapter 8, but here’s a brief explanation:

![]() The site is using some kind of navigation structure that search engines can’t read, so they can’t find their way through the site.

The site is using some kind of navigation structure that search engines can’t read, so they can’t find their way through the site.

![]() The site is creating dynamic pages that search engines choose not to read.

The site is creating dynamic pages that search engines choose not to read.

Unreadable navigation

Many sites have perfectly readable pages, with the exception that the searchbots — the programs search engines use to index Web sites — can’t negotiate the site navigation. The searchbots can reach the home page, index it, and read it, but they can’t go any further. If, when you search Google for your pages, you find only the home page, this could be the problem.

Why can’t the searchbots find their way through? The navigation system may have been created using JavaScript, and because search engines mostly ignore JavaScript, they don’t find the links in the script. Look at this example:

<SCRIPT TYPE=”javascript” SRC=”/menu/menu.js”></SCRIPT>

In many sites, this is how navigation bars are placed into each page: Pages call an external JavaScript, held in menu.js in the menu subdirectory. Search engines generally won’t read menu.js, so they’ll never read the links in the script.

![]() Create more text links throughout the site. Many Web sites have a main navigation structure and then duplicate the structure by using simple text links at the bottom of the page. You should do the same.

Create more text links throughout the site. Many Web sites have a main navigation structure and then duplicate the structure by using simple text links at the bottom of the page. You should do the same.

![]() Add an HTML sitemap page to your site. This page contains links to most or all of the pages on your Web site. Of course, you also want to link to the sitemap page from those little links at the bottom of the home page.

Add an HTML sitemap page to your site. This page contains links to most or all of the pages on your Web site. Of course, you also want to link to the sitemap page from those little links at the bottom of the home page.

Dealing with dynamic pages

In many cases, the problem is that the site is dynamic — that is, a page is created on the fly when a browser requests it. The data is pulled from a database, pasted into a Web page template, and sent to the user’s browser. Search engines sometimes won’t read such pages (though this is nowhere near as serious a problem as it was a few years ago), for a variety of reasons explained in detail in Chapter 8.

How can you tell if this is a problem? Take a look at the URL in the browser’s location bar. Suppose that you see something like this:

http://www.yourdomain.edu/rodent-racing

This address is okay. It’s a simple URL path made up of a domain name, two directory names, and a filename. Now look at this one:

http://www.yourdomain.edu/rodent-racing/

The filename ends with ?prg=1. This parameter is being sent to the server to let it know what information is needed for the Web page. If you have URLs like this, with just a single parameter, they’re probably okay, especially for Google; however, a few smaller search engines may not like them (though that’s usually no big deal, as the smaller search engines are not very important). Here’s another example:

http://yourdomain.com/products/index.html

This one may be a real problem, depending on the search engine. This URL has too much weird stuff after the filename:

?&DID=18&CATID=13&ObjectGroup_ID=79

That’s three parameters — DID=18, CATID=13, and ObjectGroup_ID=79 — and that’s too many. Some systems cannot or will not index this page.

Another problem is caused by session IDs — URLs that are different every time the page is displayed. Look at this example:

http://yourdomain.com/buyAHome.do

Each time someone visits this site, the server assigns a special ID number to the visitor. That means the URL is never the same, so Google probably won’t index it.

If you have a clean URL with no parameters, the search engines should be able to get to it. If you have a single parameter in the URL, it’s probably fine. Two parameters may not be a problem, although they’re more likely to be a problem than a single parameter. Three parameters may be a problem with some search engines. If you think you have a problem, I suggest reading Chapter 8.

Picking Good Keywords

Getting search engines to recognize and index your Web site can be a problem, as the first part of this chapter makes clear. Another huge problem — one that has little or nothing to do with the technological limitations of search engines — is that many companies have no idea what keywords (the words people are using at search engines to search for Web sites) they should be using. They try to guess the appropriate keywords, without knowing what people are really using in search engines.

In Chapter 6, I explain keywords in detail, but here’s how to do a quick keyword analysis:

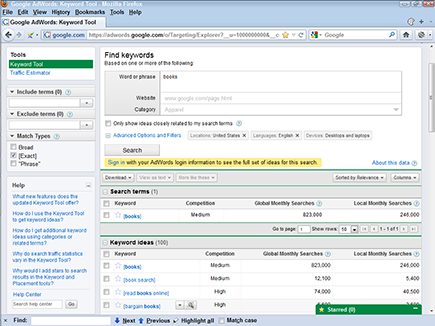

1. Point your browser to https://adwords.google.com/select/KeywordToolExternal.

You see the Google AdWords Keyword Tool. AdWords is Google’s PPC (pay per click) division.

2. In the search box, type a keyword you think people may use to search for your products or services and then click Search.

3. Click the Get Keyword Ideas button.

The tool returns a list of keywords, showing you how often that term and related terms are used by people searching on Google and partner sites (see Figure 3-2).

4. Reset the Match Type check boxes.

Clear the Broad Match check box in the left column and select the Exact Match box. (I explain why in Chapter 6.) The keyword list reloads.

You may find that the keyword you guessed is perfect. Or you may discover better words, or, even if your guess was good, find several other great keywords. A detailed keyword analysis almost always turns up keywords or keyword phrases you need to know about. Just recently, I spoke with someone whose site was ranking really well for his chosen keywords, but he was totally unaware that he was missing some other, very popular, terms; it’s a common problem.

Don’t spend a lot of time on this task right now. See whether you can come up with some useful keywords in a few minutes and then move on; see Chapter 6 for details about this process.

Figure 3-2: The Google AdWords Keyword Tool provides a quick way to check keywords.

Examining Your Pages

Making your Web pages “search engine–friendly” was probably not uppermost in your mind when you sat down to design your Web site. That means your Web pages — and the Web pages of millions of others — probably have a few problems in the search engine–friendly category. Fortunately, such problems are pretty easy to spot; you can fix some of them quickly, but others are more troublesome.

Using frames

To examine your pages for problems, you need to read the pages’ source code. Remember, I said you’d need to be able to understand HTML! To see the source code, choose View⇒Source or View⇒Page Source in your browser. (Or use a tool such as Firebug, an add-on designed for Firefox but available, in a lite form, for other browsers. See www.getfirebug.com.)

When you first peek at the source code for your site, you may discover that your site is using frames. (Of course, if you built the site yourself, you already know whether it uses frames. However, you may be examining a site built by someone else.) You may see something like this on the page:

<HTML>

<HEAD>

</HEAD>

<FRAMESET ROWS=”20%,80%”>

<FRAME SRC=”navbar.html”>

<FRAME SRC=”content.html”>

</FRAMESET>

<BODY>

</BODY>

</HTML>

When you choose View⇒Source or View⇒Page Source in your browser, you’re viewing the source of the frame-definition document, which tells the browser how to set up the frames. In the preceding example, the browser creates two frame rows, one taking up the top 20 percent of the browser and the other taking up the bottom 80 percent. In the top frame, the browser places content taken from the navbar.html file; content from content.html goes into the bottom frame.

Framed sites don’t index well. The pages in the internal frames get orphaned in search engines; each page ends up in search results alone, without the navigation frames with which they were intended to be displayed.

![]() Add

Add TITLE and DESCRIPTION tags between the <HEAD> and </HEAD> tags. (To see what these tags are and how they can help with your frame issues, check out the next two sections.)

![]() Add

Add <NOFRAMES> and </NOFRAMES> tags between the <BODY> and </BODY> tags and place 200 to 300 words of keyword-rich content between the tags. The NOFRAMES text is designed to be displayed by browsers that can’t work with frames, and search engines will read this text, although they won’t rate it as highly as normal text (because many designers have used <NOFRAMES> tags as a trick to get more keywords into a Web site, and because the NOFRAMES text is almost never seen these days, because almost no users have browsers that don’t work with frames).

![]() In the text between the

In the text between the <NOFRAMES> tags, include a number of links to other pages in your site to help search engines find their way through.

![]() Make sure every page in the site contains a link back to the home page, in case it’s found “orphaned” in the search index.

Make sure every page in the site contains a link back to the home page, in case it’s found “orphaned” in the search index.

Looking at the TITLE tags

TITLE tags tell a browser what text to display in the browser’s title bar and tabs, and they’re very important to search engines. Quite reasonably, search engines figure that the TITLE tags may indicate the page’s title — and, therefore, its subject.

Open your site’s home page and then choose View⇒Source in your browser to see the page source. A window opens, showing you what the page’s HTML looks like. Here’s what you should see at the top of the page:

<HTML>

<HEAD>

<TITLE>Your title text is here</TITLE>

Here are a few problems you may have with your <TITLE> tags:

![]() They’re not there. Many pages simply don’t have

They’re not there. Many pages simply don’t have <TITLE> tags. If they don’t, you’re failing to give the search engines one of the most important pieces of information about the page’s subject matter.

![]() They’re in the wrong position. Sometimes you find the

They’re in the wrong position. Sometimes you find the <TITLE> tags, but they’re way down in the page. If they’re too low in the page, search engines may not find them.

![]() There are two sets. Now and then I see sites that have two sets of <

There are two sets. Now and then I see sites that have two sets of <TITLE> tags on each page; in this case, the search engines will probably read the first and ignore the second.

![]() Every page on the site has the same

Every page on the site has the same <TITLE> tag. Many sites use the exact same tag on every single page. Bad idea! Every <TITLE> tag should be different.

![]() They’re there, but they’re poor. The

They’re there, but they’re poor. The <TITLE> tags don’t contain the proper keywords.

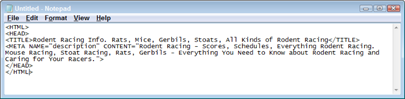

<TITLE>Rodent Racing Info. Rats, Mice, Gerbils, Stoats, All Kinds of Rodent Racing</TITLE>

Find out more about keywords in Chapter 6 and titles in Chapter 7.

Examining the DESCRIPTION tag

The DESCRIPTION tag is important because search engines may index it (under the reasonable assumption that the description describes the contents of the page) and, in many cases, use the DESCRIPTION tag to provide the site description on the search results page. Thus you might think of the DESCRIPTION tag as serving two purposes: to help with search rank and as a “sales pitch” to convince people viewing the search-results page to click your link. (Google says it doesn’t use the tag for indexing, but it’s still important because Google will often display the tag contents in the search-results page.)

Open a Web page, open the HTML source (select View⇒Source from your browser’s menu), and then take a quick look at the DESCRIPTION tag. It should look something like this:

<META NAME=”description” CONTENT=”your description goes here”>

Sites often have the same problems with DESCRIPTION tags as they do with <TITLE> tags. The tags aren’t there, are hidden away deep down in the page, are duplicated, or simply aren’t very good.

Place the DESCRIPTION tag immediately below the <TITLE> tags (see Figure 3-3) and create a keyworded description of up to 250 characters (again, including spaces). Here’s an example:

<META NAME=”description” CONTENT=”Rodent Racing - Scores, Schedules, Everything Rodent Racing. Mouse Racing, Stoat Racing, Rats, Gerbils - Everything You Need to Know about Rodent Racing and Caring for Your Racers.”>

Figure 3-3: A clean start to your Web page, showing the <TITLE> and <DESCRIP TION> tags.

Sometimes Web developers switch the attributes in the tag, putting the CONTENT= before the NAME=, like this:

<META CONTENT=”your description goes here” NAME=”description”>

Giving search engines something to read

You don’t necessarily have to pick through the HTML code for your Web page to evaluate how search engine–friendly it is. You can find out a lot just by looking at the Web page in the browser. Determine whether you have any text on the page. Page content — text that search engines can read — is essential, but many Web sites don’t have any page content on the front page and often have little or none on interior pages. Here are some potential problems:

![]() Having a (usually pointless) Flash intro on your site

Having a (usually pointless) Flash intro on your site

![]() Creating a totally Flash-based site

Creating a totally Flash-based site

![]() Embedding much of the text on your site into images, rather than relying on readable text

Embedding much of the text on your site into images, rather than relying on readable text

![]() Banking on flashy visuals to hide the fact that your site is light on content

Banking on flashy visuals to hide the fact that your site is light on content

![]() Using the wrong keywords (Chapter 6 explains how to pick keywords.)

Using the wrong keywords (Chapter 6 explains how to pick keywords.)

If you have these types of problems, they can often be time consuming to fix. (Sorry, you may run over the one-hour timetable by several weeks.) The next several sections detail ways you might overcome the problems.

Eliminating Flash

I suggest that you kill the Flash intro on your site. They don’t hurt your site in the search engines (unless, of course, you’re removing indexable text and replacing it with Flash), but they don’t help, either, and I rarely see a Flash intro that actually serves any purpose. In most cases, they’re nothing but an irritation to site visitors. (The majority of Flash intros are created because the Web designer likes playing with Flash.) And a site that is nothing but Flash — no real text; everything’s in the Flash file — is a disaster from a search engine perspective.

If you’re really wedded to your Flash intro, though — and there are occasionally some that make sense — there are ways to use Flash and still do a good job in the search engines; see Chapter 8 for information on the SWFObject method. Just don’t expect Flash on its own to work well in the search engines.

Replacing images with real text

If you have an image-heavy Web site, in which all or most of the text is embedded onto images, you need to get rid of the images and replace them with real text. If the search engine can’t read the text, it can’t index it.

![]() Try to select the text in the browser with your mouse. If it’s real text, you can select it character by character. If it’s not real text, you simply can’t select it — you’ll probably end up selecting an image.

Try to select the text in the browser with your mouse. If it’s real text, you can select it character by character. If it’s not real text, you simply can’t select it — you’ll probably end up selecting an image.

![]() Right-click the text, and if you see menu options, such as Save Image and Copy Image, you know it’s an image, not text.

Right-click the text, and if you see menu options, such as Save Image and Copy Image, you know it’s an image, not text.

Using more keywords

The light-content issue can be a real problem. Some sites are designed to be light on content, and sometimes this approach is perfectly valid in terms of design and usability. However, search engines have a bias for content — that is, for text they can read. (I discuss this issue in more depth in Chapter 10.) In general, the more text — with the right keywords — the better.

Using the right keywords in the right places

Suppose that you do have text, and plenty of it. But does the text have the right keywords? The ones discovered with the Google AdWords Keyword Tool earlier in this chapter? It should.

Where keywords are placed and what they look like is also important. Search engines use position and format as clues to importance. Here are a few simple techniques you can use — but don’t overdo it!

![]() Use keywords in folder names and filenames, and in page files and image files.

Use keywords in folder names and filenames, and in page files and image files.

![]() Use keywords near the top of the page.

Use keywords near the top of the page.

![]() Place keywords into

Place keywords into <H> (heading) tags.

![]() Use bold and italic keywords; search engines take note of these.

Use bold and italic keywords; search engines take note of these.

![]() Put keywords into bulleted lists; search engines also take note of this.

Put keywords into bulleted lists; search engines also take note of this.

![]() Use keywords multiple times on a page, but don’t use a keyword or keyword phrase too often. If your page sounds really clumsy through over-repetition, it may be too much.

Use keywords multiple times on a page, but don’t use a keyword or keyword phrase too often. If your page sounds really clumsy through over-repetition, it may be too much.

Ensure that the links between pages within your site contain keywords. Think about all the sites you’ve visited recently. How many use links with no keywords in them? They use buttons, graphic navigation bars, short little links that you have to guess at, click here links, and so on. Big mistakes.

To reiterate, when you create links, include keywords in the links wherever possible. For example, on your rodent-racing site, if you’re pointing to the scores page, don’t create a link that says To find the most recent rodent racing scores, click here or, perhaps, To find the most recent racing scores, go to the scores page. Instead, get a few more keywords into the links, like this: To find the most recent racing scores, go to the rodent racing scores page. That tells the search engine that the referenced page is about rodent racing scores.

Getting Your Site Indexed

So your pages are ready, but you still have the indexing problem. Your pages are, to put it bluntly, just not in the search engine! How do you fix that problem?

For Yahoo! Directory and the Open Directory Project, you have to go to those sites and register directly, but before doing that, you should read Chapter 13. With Google, Bing, and Ask.com, the process is a little more time consuming and complicated.

The best way to get into the search engines is to have them find the pages by following links pointing to the site. In some cases, you can ask the search engines to come to your site and pick up your pages. However, if you ask search engines to index your site, they probably won’t do it. And if they do come and index your site, doing so may take weeks or months. Asking them to come to your site is unreliable.

So how do you get indexed? The good news is that you can often get indexed by some of the search engines very quickly.

Find another Web site to link to your site, right away. I’m not talking about a full-blown link campaign here, with all the advantages I describe in Chapters 15 and 16. You simply want to get search engines — particularly Google, Bing, and Ask.com — to pick up the site and index it. Call friends, colleagues, and relatives who own or control Web sites, and ask them to link to your site; many people have blogs these days, or even social-networking pages they can link from. Of course, you want sites that are already indexed by search engines. The searchbots have to follow the links to your site.

By the way, I recommend that you use simple characters in your link text; use a single hyphen to separate words, as I did here, not typographic characters, such as em dashes or en dashes.

After the sites have links pointing to yours, it can take from a few days to a few weeks to get into the search engines. With Google, if you place the links right before Googlebot indexes one of the sites, you may be in the index in a few days. I once placed some pages on a client’s Web site on a Tuesday and found them in Google (ranked near the top) on Friday. But Google can also take several weeks to index a site. The best way to increase your chances of getting into search engines quickly is to get as many links as you can on as many sites as possible.

You should also create an XML sitemap, submit that to Google and Bing, and add a line in your robots.txt file that points to the sitemap so that search systems — such as Ask.com — that don’t provide a way for you to submit the sitemap can still find it. You find out all about that in Chapter 12.

Various browser add-ons, such as SEOQuake, automatically tell you the number of indexed pages when you visit a site.

Various browser add-ons, such as SEOQuake, automatically tell you the number of indexed pages when you visit a site. A

A  Your

Your