Figure 6-1: A page designed for the spelling challenged.

Chapter 6

Picking Powerful Keywords

In This Chapter

![]() Thinking up keyword phrases

Thinking up keyword phrases

![]() Using the free Google Keyword tool

Using the free Google Keyword tool

![]() Using Wordtracker

Using Wordtracker

![]() Sifting for the right keywords

Sifting for the right keywords

I was talking with a client some time ago who wanted to have his site rank well in the search engines. The client is a company with annual revenues in the millions of dollars, in the business of, oh, I don’t know . . . staging rodent-racing events. (I’ve changed the details of this story a tad to protect the guilty.)

I did a little research and found that most people searching for rodent-racing events use the keywords rodent racing. (Big surprise, huh?) I took a look at the client’s Web site and discovered that the words rodent racing didn’t appear anywhere on the site’s Web pages.

“You have a little problem,” I said. “Your site doesn’t use the words rodent racing, so it’s unlikely that any search engine will find your site when people search for that.”

“Oh, well,” was the client’s reply, “our marketing department objects to the term. We have a company policy to use the term furry friend events. The term rodent is too demeaning, and if we say we’re racing them, the animal rights people will get upset.”

This is a true story; well, except for the bit about rodent racing and the furry friends thing. But, in principle, it happened. This company had a policy not to use the words that most of its potential clients were using to search for it.

This is an unusual example, in which a company knows the important keywords but decides not to use them. But, in fact, many companies build Web sites only to discover later that the keywords its potential clients and visitors are using are not in the site. How is that possible? Well, I can think of a couple of reasons:

![]() Most sites are built without any regard for search engines. The site designers simply don’t think about search engines or have little background knowledge about how search engines work.

Most sites are built without any regard for search engines. The site designers simply don’t think about search engines or have little background knowledge about how search engines work.

![]() The site designers do think about search engines, but they guess, often incorrectly, what keywords they should be using.

The site designers do think about search engines, but they guess, often incorrectly, what keywords they should be using.

I can’t tell you how the client and I resolved his problem because, well, we didn’t. (Sometimes company politics trump common sense.) But in this chapter, I explain how to pick keywords that make sense for your site, as well as how to discover what keywords your potential site visitors are using to search for your products and services.

Understanding the Importance of Keywords

When you use a search engine, you type in a word or words and click the Search button. The search engine then looks in its index for those words.

Suppose that you typed rodent racing. Generally speaking, the search engine looks for

![]() Pages that contain the exact phrase rodent racing

Pages that contain the exact phrase rodent racing

![]() Pages that don’t have the phrase rodent racing but do have the words rodent and racing in close proximity

Pages that don’t have the phrase rodent racing but do have the words rodent and racing in close proximity

![]() Pages that have the words rodent and racing somewhere, though not necessarily close together

Pages that have the words rodent and racing somewhere, though not necessarily close together

![]() Pages with word stems; for instance, pages with the word rodent and the word race somewhere in the page

Pages with word stems; for instance, pages with the word rodent and the word race somewhere in the page

![]() Pages with synonyms, such as, perhaps, mouse and rat

Pages with synonyms, such as, perhaps, mouse and rat

![]() Pages that have links pointing to them, in which the link text contains the phrase rodent racing

Pages that have links pointing to them, in which the link text contains the phrase rodent racing

![]() Pages with links pointing to them with the link text containing the words rodent and racing, although not together

Pages with links pointing to them with the link text containing the words rodent and racing, although not together

The process is actually a lot more complicated. The search engine doesn’t necessarily show pages in the order I just listed — all the pages with the exact phrase, and then all the pages with the words in close proximity, and so on. When considering ranking order, the search engine considers (in addition to hundreds of secret criteria) whether the keyword or phrase is in

![]() Bold text

Bold text

![]() Italicized text

Italicized text

![]() Bulleted lists

Bulleted lists

![]() Text larger than other text on the page

Text larger than other text on the page

![]() Heading text (

Heading text (<H> tags)

Despite the various complications, however, one fact is of paramount importance: If a search engine can’t relate your Web site to the words that someone searches for, it has no reason to return your Web site as part of the search results.

Picking the right keywords is critical. As Woody Allen once said, “Eighty percent of success is showing up.” If you don’t play the game, you can’t win. And if you don’t choose the right keywords, you’re not even showing up to play the game. If a specific keyword or keyword phrase doesn’t appear in your pages (or in links pointing to your pages), your site will not appear when someone enters those keywords into the search engines. For instance, say you’re a technical writer in San Diego, and you have a site with the term technical writer scattered throughout. You will not appear in search results when someone searches for technical writer san diego if you don’t have the words San Diego in your pages. You simply will not turn up (unless you are listed in the local search results, a subject I deal with in Chapter 11).

Thinking Like Your Prey

It’s an old concept: You should think like your prey. Companies often make mistakes with their keywords because they choose based on how they — rather than their customers — think about their products or services. For example, lawyers talk about practice areas, a phrase ordinary people — lawyers’ clients — almost never use. You have to stop thinking that you know what customers call your products. Do some research to find out what clients really do call your products and services.

The starting point of any great SEO strategy is a thorough keyword analysis. Check to see what people are actually searching for on the Web. You’ll discover that the words you were positive people would use are rarely searched, and you’ll also find that you’ve missed a lot of common terms. Sure, you may get some of the keywords right; however, if you’re spending time and energy targeting particular keywords, you may as well get ’em all right.

![]() When I use it, I’m referring to what I’m discussing in this chapter — analyzing the use of keywords by people searching for products, services, and information.

When I use it, I’m referring to what I’m discussing in this chapter — analyzing the use of keywords by people searching for products, services, and information.

![]() Some people use the term to mean keyword-density analysis — finding out how often a keyword appears in a page. Some of the keyword analysis tools that you run across are actually keyword-density analysis tools.

Some people use the term to mean keyword-density analysis — finding out how often a keyword appears in a page. Some of the keyword analysis tools that you run across are actually keyword-density analysis tools.

![]() The term also refers to the process of analyzing keywords in your Web site’s access logs.

The term also refers to the process of analyzing keywords in your Web site’s access logs.

Starting Your Keyword Analysis

Perform a keyword analysis — a check of what keywords people use to search on the Web — or you’re wasting your time. Imagine spending hundreds of hours optimizing your site for a keyword you think is good, only to discover that another keyword or phrase gets two or three times the traffic. How would you feel? Sick? Stupid? Mad? Don’t risk your mental health — do it right the first time.

Identifying the obvious keywords

Begin by typing the obvious keywords into a text editor or word processor. Type the words you’ve already thought of, or, if you haven’t started yet, the ones that immediately come to mind. Then study the list for a few minutes. What else can you add? What similar terms come to mind? Add them, too.

When you perform your analysis, you’ll find that some of the initial terms you think of aren’t searched very often, but that’s okay. This list is just the start.

Looking at your Web site’s access logs

Take a quick look at your Web site’s access logs (often called hit logs). You may not realize it, but most logs show you the keywords that people used when they clicked a link to your site at a search engine. (If your logs don’t contain this information, you probably need another program.) Write down the terms that are bringing people to your site.

Examining competitors’ keyword tags

You probably know who your competitors are — you should, anyway. Go to their sites and open the source code of a few pages by following these steps:

1. Choose View⇒Source from the browser’s menu bar.

2. Look in the <META NAME=“keywords”> tag for any useful keywords.

Often, the keywords are garbage or simply not there, but if you look at enough sites, you’re likely to come up with some useful terms you hadn’t thought of.

Brainstorming with colleagues

Talk to friends and colleagues to see whether they can come up with some possible keywords. Ask them something like, “If you were looking for a site where you could find the latest scores for rodent races around the world, what terms would you search for?” Give everyone a copy of your current keyword list and ask whether they can think of anything to add. Usually, reading the terms sparks an idea or two, and you end up with a few more terms.

Looking closely at your list

After you’ve put together your initial list, go through it looking for more obvious additions. Don’t spend too much time on this; all you’re doing here is creating a preliminary list to run through a keyword tool, which figures out some of these things for you.

Obvious spelling mistakes

Scan through your list and see if you can think of any obvious spelling mistakes. Some spelling mistakes are incredibly important, with 10, 15, or 20 percent (sometimes even more) of all searches containing the misspelled word. For example, about one-fifth of all Britney Spears–related searches are misspelled — spread out over a dozen misspellings. I’m not commenting on the intellect of Britney Spears fans . . . it’s just a name that could be spelled several ways.

The word calendar is also frequently misspelled. Look at the following estimate of how often calendar is searched for each day in its various permutations:

calendar: 10,605 times

calender: 2,721

calander: 1,549

calandar: 256

Thirty percent of all searches on the word calendar are misspelled. (Where do I get these estimates, you’re wondering? You find out later in this chapter in the “Using a Keyword Tool” section.)

One nice thing about misspellings is that competitors often miss them, so you can grab the traffic without much trouble.

“But Google recognizes spelling mistakes, doesn’t it?” I can hear you thinking. Yes, it does, and it handles them in a couple of ways. In some cases, when Google is pretty sure that it was a spelling mistake, it goes ahead and searches for the assumed correct spelling and puts a line like this near the top of the page:

Showing results for free currency converter. Search instead for free currancy converter

On the other hand, sometimes Google isn’t so sure, and it displays a couple of entries that have the assumed correct spelling, followed by another eight entries that are misspelled.

Synonyms

Sometimes similar words are easily missed. If your business is home related, for instance, have you thought about the term house? Americans may easily overlook this word, using home instead, but other English-speaking countries use the word house more often. Add it to the list because you may find quite a few searches related to it.

You might even use a thesaurus to find more synonyms. However, I show you some keyword tools that run these kinds of searches for you; see the section “Using a Keyword Tool,” later in this chapter.

Split or merged words

You may find that although your product name is one word — RodentRacing, for instance — most people are searching for you by using two words, rodent and racing. Remember to consider your customer’s point of view.

Also, some words are employed in two ways. Some people, for instance, use the term knowledgebase, while others use knowledge base. Which is more important? Both should be on your list, but knowledge base is used around four to five times more often than knowledgebase. If you optimize your pages for knowledgebase (I discuss page optimization in Chapter 7), you’re missing out on around 80 percent of the traffic!

Singulars and plurals

Go through your list and add singulars and plurals. Search engines understand plurals and often return plural results when you search for a singular term and vice versa, but they still treat singulars and plurals differently, and sometimes this can mean the difference between ranking at #1 and not ranking at all. For example, searching on rodent and rodents provides different results; therefore, it’s important to know which term is searched for most often. A great example is to do a search on book (165,000 U.S. searches per month, according to the Google keyword tool, which I discuss later in this chapter) and books (246,000 searches per day) in Google. A search on book returns Barnes and Noble as the #1 result, followed by Google Books, and then Facebook and doesn’t get to Amazon until position #6 (after a bunch of local results; whereas books returns Amazon in position #3, and Facebook is nowhere to be seen.

Hyphens

Do you see any hyphenated words on your list that could be used without the hyphen, or vice versa? Some terms are commonly used both ways, so find out what your customers are using. Here are two examples:

![]() Google reports that the term e-commerce is used far more often than ecommerce.

Google reports that the term e-commerce is used far more often than ecommerce.

![]() The dash in e-mail is far less frequently used, with email being by far the most common term.

The dash in e-mail is far less frequently used, with email being by far the most common term.

Find hyphenated words, add both forms to your list, and determine which is more common, because search engines treat them as different searches.

Geo-specific terms

Is geography important to your business? Are you selling shoes in Seattle or rodents in Rochester? Don’t forget to include terms that include your city, state, other nearby cities, and so on. (See Chapter 11 for more on this topic.)

Your company name

If you have a well-known company name, add that to the list, in whatever permutations you can think of (for example, Microsoft, MS, MSFT, and so on).

Other companies’ names and product names

If people are likely to search for companies and products similar to yours, add those companies and products to your list. That’s not to say you should use these keywords in your pages (you can in some conditions, as I discuss in Chapter 7), but it’s nice to know what people are looking for and how often they’re looking.

Using a Keyword Tool

After you’ve put together a decent keyword list, the next step is to use a keyword tool. This tool enables you to discover additional terms you haven’t thought of and helps you determine which terms are most important — which terms are used most often by people looking for your products and services.

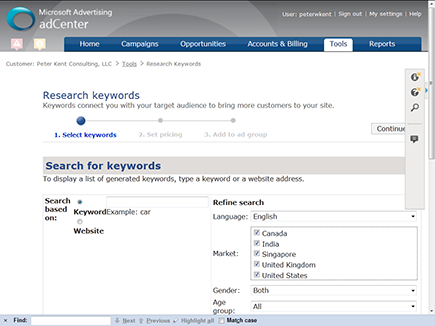

Both free and paid versions of keyword tools are available. Both the major PPC (Pay Per Click) advertising systems provide keyword-analysis tools, though for Bing you have to sign up for a PPC account (or at least begin the process; Yahoo!’s PPC system is now run through the Bing system, Microsoft adCenter). For instance, go to http://adcenter.microsoft.com and begin the signup process for a Bing PPC account. (Don’t worry, you won’t have to pay anything until you get way past the keyword analysis tool.)

You tell Bing where you want to run your ads in the first step, create an ad in the second step, and then, in the third step, you pick your keywords. You see a page similar to that shown in Figure 6-2.

Figure 6-2: The Bing (Microsoft AdCenter) PPC Keyword Analysis tool.

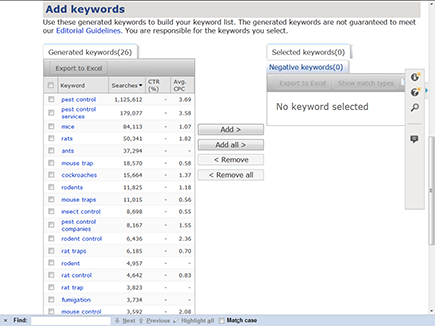

You enter some keywords and then click Next. A screen similar to Figure 6-3 appears.

This screen shows a list of suggested keywords with an estimate of the number of searches for that term in the previous month.

You can go down the list clicking the check boxes next to the keywords you want to use and then click the Add Keywords button at the top of the list to place those keywords into the keywords box top left; you can copy the keywords out of that box if you want.

Using the free Google keyword tool

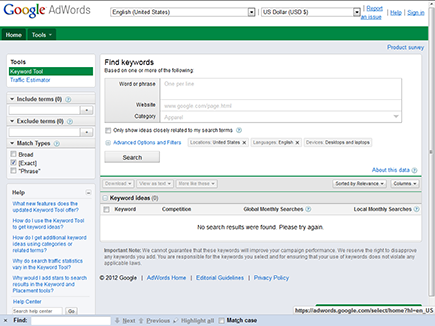

Rather than use one of these half-hidden keyword tools from one of the smaller search engines, you can go directly to Google’s keyword tool, here: https://adwords.google.com/select/KeywordToolExternal. This is a great keyword tool, as long as you understand a couple of things.

Figure 6-3: Bing (Microsoft AdCenter) Analysis tool results.

First, be aware that unless you sign up for a Google AdWords PPC account, Google doesn’t show you all the results; you get only the first 100. You can sign up for an AdWords account (www.adwords.com) without running any ads (and thus without paying for anything).

The other thing to understand is exactly what Google is showing you; there’s a lot of confusion among users here, and you have to select the correct options to get the information you need, so listen closely.

When you first view the Google Keyword tool, you see a page like the one shown in Figure 6-4. You have two ways to get started:

![]() Type a keyword into the Word or Phrase box or type multiple phrases if you like, each on a separate line.

Type a keyword into the Word or Phrase box or type multiple phrases if you like, each on a separate line.

![]() Type the domain name of a Web site into the Website box. Google pulls keywords from this site.

Type the domain name of a Web site into the Website box. Google pulls keywords from this site.

![]() Select one or more categories from the grayed-out drop-down list box under the Web site text box.

Select one or more categories from the grayed-out drop-down list box under the Web site text box.

In effect, you’re telling Google to look through its database of searches — actual keywords typed in by real searchers on its Web site and partner sites — to find searches that it thinks may be related to your keyword phrase, the Web site you entered, or the category you picked. (You can mix these up, too; search for the term queen in the Food & Groceries category, and Google finds terms that mainly seem related to dairy queen.) Note that you can also click the Advanced Options and Filters link under the Word or Phrase box to specify criteria even more. You can

![]() Limit the keywords to searches within a particular country or language.

Limit the keywords to searches within a particular country or language.

![]() Include adult keywords, if you want.

Include adult keywords, if you want.

![]() Limit the information to only searches carried out on mobile devices (not including phones with full browsing capabilities — just those with simple Internet data access).

Limit the information to only searches carried out on mobile devices (not including phones with full browsing capabilities — just those with simple Internet data access).

![]() Filter results by using various criteria, such as “global monthly searches over 100,000” or “show low competition keywords only.”

Filter results by using various criteria, such as “global monthly searches over 100,000” or “show low competition keywords only.”

Figure 6-4: Google’s free keyword analysis tool.

You must understand this!

Remember, this is really an AdWords tool, a service intended to help you work with your Google PPC ads. When you click Search, the tool is going to return with a list of keywords and show you Monthly Searches. The number shown in the Monthly Searches depends on your Match Types box.

Okay, bear with me; those of you who understand PPC probably already know what I’m getting at, but give me a moment and let me explain. First, a very quick explanation of PPC ads. When an advertiser places a PPC ad into one of the ad systems, such as AdWords, she has to say when the ad should run. So, for instance, the ad could be specified to run when someone searches for rodent racing or rodent. The ad is matched to a keyword or group of keywords typed into the search engine by a searcher.

The Match Type check boxes determine how a PPC ad would be matched with a search term:

![]() Broad: This is the default match type. When someone searches for a phrase that Google believes is “similar” or a “relevant variation,” the ad is triggered. Broad match keywords can have very unpredictable results because an ad may be triggered by many different searches. For instance, if an ad were triggered by a broad match of rodent racing, the ad may be triggered when someone searches for not just rodent racing but also squirrels attic, mice trap, and kill rat. That’s pretty darn broad.

Broad: This is the default match type. When someone searches for a phrase that Google believes is “similar” or a “relevant variation,” the ad is triggered. Broad match keywords can have very unpredictable results because an ad may be triggered by many different searches. For instance, if an ad were triggered by a broad match of rodent racing, the ad may be triggered when someone searches for not just rodent racing but also squirrels attic, mice trap, and kill rat. That’s pretty darn broad.

![]() [Exact]: Using an Exact match, the keyword phrase triggers the ad only if someone searches for that exact phrase. For instance, if an ad is triggered by the keyword phrase rodent racing using an Exact match, the ad appears only if someone searches for the exact phrase rodent racing.

[Exact]: Using an Exact match, the keyword phrase triggers the ad only if someone searches for that exact phrase. For instance, if an ad is triggered by the keyword phrase rodent racing using an Exact match, the ad appears only if someone searches for the exact phrase rodent racing.

![]() Phrase: Using Phrase match, an ad appears when someone searches for the exact phrase, or for the exact phrase in combination with other words. For instance, if an ad is set to trigger on the phrase rodent racing set to Phrase match, the ad may be triggered when someone searches for rodent racing scores (though not for racing rodent scores).

Phrase: Using Phrase match, an ad appears when someone searches for the exact phrase, or for the exact phrase in combination with other words. For instance, if an ad is set to trigger on the phrase rodent racing set to Phrase match, the ad may be triggered when someone searches for rodent racing scores (though not for racing rodent scores).

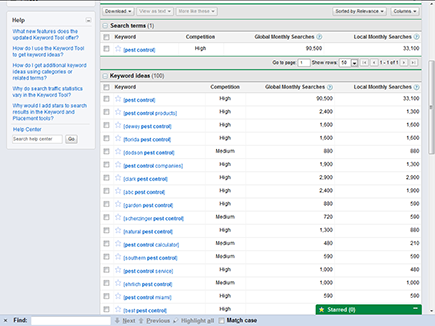

Now you can understand the importance of the Match Type setting. If you search for, for instance, pest control with Broad Match selected, Google may tell you that there are 1,000,000 Local Monthly Searches; search with Exact Match selected, and you’ll find that there are actually 33,100 searches for that phrase each month. (These are the numbers I got when I tried it, with the location set to the United States.) You can, of course, search with both match types selected, and you’ll get both numbers; Google will show the Exact Match keyword enclosed in brackets ([pest control]) and the Broad Match keyword not enclosed. You can search for Phrase match, too (the keywords will be enclosed in quotation marks — “pest control”).

Sorry, this concept takes a bit of explaining, but it’s important. Google’s keyword tool is incredibly popular; it’s free, and it has the best data — Google data. But most users don’t understand what they are looking at, and I don’t want you to be included among that crowd.

Begin your search

When you’ve made all your selections, click the Search button, and Google finds keywords related to your search term. In the case of a category search, Google finds keywords related to that category. In the case of the Web site search, Google looks at the words it finds in the Web site and then finds keywords related to those words. Whichever method you choose, you see something like Figure 6-5.

Figure 6-5: Search results in Google’s free keyword analysis tool.

So, Google has returned perhaps 100 keyword ideas — many more if you logged into your AdWords account first — and you can click the column headings to sort them. Figure 6-5 shows the keywords sorted by Local Monthly Searches. (You can add or remove columns, by the way, using the Views button on the right side of the table.)

The Google keyword tool is great. I keep a button on my browser’s bookmarks toolbar to take me there whenever I feel a sudden urge for more keywords. Note that you can download the list of keywords, or selected keywords, into a spreadsheet (see the Download button, top left of the table), which is very handy for saving keyword analyses. However, Google doesn’t have some of the sophisticated keyword-analysis features that other, commercial keyword-analysis tools have . . . so I look at that subject next.

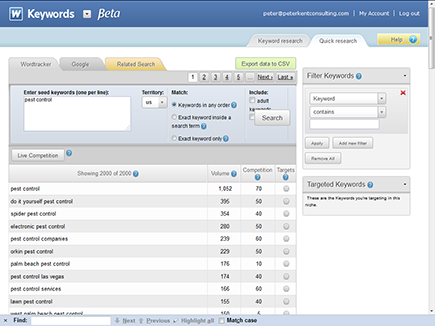

Using Wordtracker

Wordtracker (www.wordtracker.com; see Figure 6-6) is perhaps the most popular commercial keyword tool among SEO professionals. Owned by a company in London, England, Wordtracker has access to data from a couple of large metacrawlers, and a large British ISP. A metacrawler is a system that searches multiple search engines for you. For example, type a word into Dogpile’s search box (www.dogpile.com), and the system searches at Google, Yahoo!, Bing, and Ask.com.

Wordtracker’s database has hundreds of million searches from the last 365 days. Wordtracker allows its customers to search this database. Ask Wordtracker how often someone searched for the term rodent, and it tells you that it was searched for (at the time of writing) 60 times over the last year but that the term rodents is far more popular, with 269 searches over the last 365 days. (Those numbers don’t sound like much, especially when compared to numbers that you’ll find through Google. But Wordtracker is working with a much smaller database than Google is — 700 million or so, compared with over 140 billion in Google’s monthly dataset. In any case, what really counts are the relative numbers; you want to know which keywords are more popular than others.)

Wordtracker also allows queries using the Google keyword tool to get Google’s information, too (though the data is modified slightly).

Figure 6-6: Wordtracker’s Quick Research screen.

Also, some searches may be influenced by the media. While searches for paris hilton were very high in November and December 2003, when I wrote the first edition of this book . . . oh, bad example, they’re still absurdly high, unfortunately. Okay, here’s another example. Early on in a catastrophe getting wide media coverage, such as a revolution in a Middle Eastern country, (such as libya or syria news — although nowhere near as high as for paris hilton . . . no, really!). But such searches drop off quickly when media coverage has waned.

Here’s what information Wordtracker can provide:

![]() The number of times in the last year that the exact phrase you enter was searched for out of 700 million or so searches

The number of times in the last year that the exact phrase you enter was searched for out of 700 million or so searches

![]() How often phrases containing the phrase you entered were searched for

How often phrases containing the phrase you entered were searched for

![]() Similar terms and synonyms, and the search statistics about these terms

Similar terms and synonyms, and the search statistics about these terms

![]() Google’s search statistics for the keywords

Google’s search statistics for the keywords

![]() An estimate of competing Web pages — the number of Web pages it found that are optimized for each keyword; the higher the number in the Competition column, the more optimized pages and the harder the task of ranking your page highly

An estimate of competing Web pages — the number of Web pages it found that are optimized for each keyword; the higher the number in the Competition column, the more optimized pages and the harder the task of ranking your page highly

You can download the list of keywords you find in a CSV file that you can quickly open in your spreadsheet program (such as Microsoft Excel).

On the face of it, Wordtracker may seem much the same as the Google tool, but it does have some additional features that help you manage your keyword lists. It allows you to set up campaigns (each Web site might be an individual campaign, for instance), and, within each campaign, multiple projects (each project could be a particular keyword focus). Then you can search for keywords and save the lists into your projects.

You can also add ranking reports to the projects. In other words, Wordtracker will go and check the position of your site in Google for up to 100 keywords; you can even have Wordtracker tell you how well your competitors rank for those keywords. The project page also contains a panel with some basic information about your Web site; whether Google and Bing have indexed your site and even whether you have errors on your site.

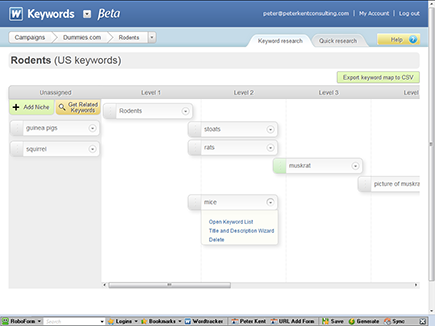

Wordtracker also has an interesting Keyword Mapping screen (see Figure 6-7), which lets you build keyword hierarchies that may help you visualize your site from a keyword perspective, grouping pages according to keywords. This tool is also an interesting way to automate the process of keyword research. Start with a single term (rodents, for instance), and Wordtracker creates a series of lists, based on words associated with your original term. (It may create lists for rats, guinea pigs, mice, muskrat, and squirrel, for instance.) You can then add your own words, and for each word, Wordtracker builds another list. Within seconds, you have a variety of terms, each with a list of dozens, if not hundreds, of associated terms. You then drag the terms onto the hierarchy as you see fit and open each term to view the full list. You then select the keywords within each list that you want to target.

Figure 6-7: Wordtracker’s Quick Research screen.

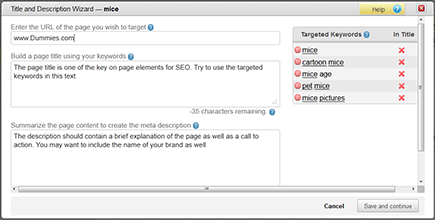

The next step is the built-in Title and Description wizard (see Figure 6-8), which helps you quickly create page URLs, HTML Titles, and Description meta tags (see Chapter 7) for the keyworded pages you’re going to build. This is a great new innovation that fits in nicely with a technique I use when designing a new site.

I build Web sites. And by that, I mean I have other people build Web sites; I’m getting too old to actually work, so I tell other people what to do. So when I’m designing a new, smallish site (this process doesn’t work well for huge sites), for myself or a consulting client, I create a spreadsheet that contains a list of all the pages in the Web site. For each page, I specify the URL I want to use, the page’s Title tag, the Description tag, the heading at the top of the page, where the content will come from (an existing Web page, or a document that will be provided later for instance), and so on. I then give this document to the developer who is going to put the site together, so there’s no question about where all the keywords go. I end up with the URLs I want, the Title tags I want, and so on.

Figure 6-8: The Title and Description Wizard page helps you output a spreadsheet that can be provided to the developer.

Well, Wordtracker’s new Title and Description wizard can be a starting point for this sort of process. You begin by building your lists of keywords and then use the wizard to create the URLs, Titles, and Descriptions for each keyword you want to focus on in the site. (Each keyword will be associated with a particular page.) When you click the Export Keyword Map to CSV button, you end up with a spreadsheet containing a line for each page, with each page’s URL, Title, and so on. Of course, you can then add any information you need before handing it off to the developer.

Wordtracker is well worth the price: $69 for a month or $449 for a year. Anyone heavily involved in the Web and search engines can easily get addicted to this tool.

Yet more keyword tools

Though Wordtracker may be the most popular keyword-analysis tool on the market, it’s certainly not the only one.

Another one is KeywordSpy (www.keywordspy.com). This slick-looking system seems to focus primarily on keywords for pay-per-click campaigns, though some of its tools could be useful for organic campaigns, too. It’s also a useful competitive-analysis tool, because by tracking PPC ads being run on Google, the system can see what keywords your competitors are bidding on. The data it holds related to organic searches comes from “publicly available information from various sources such as ISPs log files” (Web site traffic logs contain keywords that visitors at the site used to find the site). KeywordSpy also has historical data, so you can see how keyword use may have changed over time.

Yet another keyword-analysis tool is Trellian’s Keyword Discovery (www.keyworddiscovery.com). This tool gathers data by monitoring searches carried out by 4 million Web users through the use of the Trellian toolbar (www.trellian.com/toolbar), along with PPC data it pulls from Google and Bing. One of the nice things about Keyword Discovery is that you can gather research keywords regionally; you can discover what keywords people are using in different areas of the world.

You may also want to check out Wordze (www.wordze.com), an interesting service that provides historical keyword data, information on keywords in links pointing to many comparative sites, and so on.

If you are a real keyword junkie, just do a search for keyword analysis; you’ll find plenty to keep you busy.

Choosing Your Keywords

When you’ve finished working with a keyword tool, look at the final list to determine how popular a keyword phrase actually is. You may find that many of your original terms are not worth bothering with. My clients often have terms on their preliminary lists — the lists they put together without the use of a keyword tool — that are virtually never used. You also find other terms near the top of the final list that you hadn’t thought about.

Cam again? You might be missing the target

Take a look at your list to determine whether you have any words that may have different meanings to different people. Sometimes, you can immediately spot such terms.

One of my clients thought he should use the term cam on his site. To him, the term referred to Complementary and Alternative Medicine. But to the vast majority of searchers, cam means something different. Search Wordtracker on the term cam, and you come up with phrases such as web cams, web cam, free web cams, live web cams, cam, cams, live cams, live web cams, and so on. To most searchers, the term cam refers to Web cams — cameras used to place pictures and videos online. The phrases from this example generate a tremendous amount of competition, but few of them would be useful to my client. That’s okay, though, because very few people who are interested in Complementary and Alternative Medicine use the term cam anyway.

Ambiguous terms

A client of mine wanted to promote a product designed for controlling fires. One common term he came up with was fire control system. However, he discovered that when he searched on that term, most sites that turned up don’t promote products relating to stopping fires. Rather, they’re sites related to fire control in the military sense — weapons-fire control.

This kind of ambiguity is something you really can’t determine from a system that tells you how often people search on a term, such as Wordtracker. In fact, spotting such terms is hard even when you search to see what turns up when you use the phrase. If a particular type of Web site turns up when you search for the phrase, does that mean that people using the phrase are looking for that type of site? You can’t say for sure, though such a search can often tip you off that you’re working with an ambiguous term.

Very broad terms

Look at your list for terms that are incredibly broad. You may be tempted to go after high-ranking words, but make sure that people are really searching for your products when they type in the word.

Suppose that your site is promoting degrees in information technology. You discover that around 40 people search for this term each day, but approximately 1,500 people a day search on information technology. Do you think many people searching on information technology are really looking for a degree? Probably not. Although the term generates 40,000 to 50,000 searches a month, few of these returns will be your targets.

Here are a couple of reasons to forego a term that’s too broad:

![]() Tough to rank. It’s probably a very competitive term, which means ranking well on it would be difficult.

Tough to rank. It’s probably a very competitive term, which means ranking well on it would be difficult.

![]() Relevance is elsewhere. You may be better off spending the time and effort focusing on another, more relevant term.

Relevance is elsewhere. You may be better off spending the time and effort focusing on another, more relevant term.

Picking combinations

Suppose that you’re selling an e-commerce system and find the following list in Wordtracker, with the most popular term at the top:

ecommerce

e-commerce

shopping cart

shopping carts

shopping cart software

ecommerce solutions

ecommerce software

ecommerce software solution

e-commerce solutions

e-commerce software

shopping carts and accessories

The term e-commerce is probably not a great term to target because it’s very general and has a lot of competition. But lower on the list is the term e-commerce solutions. This term is a combination of two keyword phrases: e-commerce and e-commerce solutions. If you target e-commerce solutions and optimize your Web pages for that term, you’re also optimizing for e-commerce.

Notice also the term ecommerce (which search engines regard as different from e-commerce) and the term a little lower on the list, ecommerce software. A term even lower encompasses both of these terms — ecommerce software solution. Optimize your pages for ecommerce software solution, and you’ve just optimized for three terms simultaneously.

The keyword analysis procedure I describe in this chapter provides you with a much better picture of your keyword landscape. In contrast to the majority of Web site owners, you’ll have a good view of how people are searching for your products and services.

Understanding how to search helps you understand the role of keywords. Check out the bonus chapter I’ve posted at

Understanding how to search helps you understand the role of keywords. Check out the bonus chapter I’ve posted at