|

6 |

IT Security Policy Frameworks |

AN INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY (IT) security policy framework is the foundation of an organization’s information security program. The framework consists of a library of documents. A policy framework is much more than “just” a collection of documents. Organizations use these documents to build process, determine acceptable technologies, and lay the foundation for enforcement. The security policy framework documents and their implementation express management’s view of the importance of information security.

Security policies frameworks can be large and complex, with significant impacts to the organization. Implementation requires strong management support and good planning. There are many individual tasks and issues to resolve along the way. Maintaining a clear line of communication with the executives who demonstrate support for and, ideally, personal commitment to the implementation is important. The implementation is not complete when a policy framework is published. The framework must define the business as usual (BAU) activities and accountabilities needed to ensure information security policies are maintained. You can measure success by how well the framework helps reduce risk to the organization. Implementing the framework is only one of the first steps in managing information security risks.

Organizations cannot afford to be reactive or operate in an ad-hoc fashion regarding information security. There’s increased accountability and liability with regulations. There’s increased demand from senior leadership to demonstrate value. There’s a push from security professionals to measure success. However, before you can measure anything, you need a benchmark. A benchmark allows you to gauge if you’ve reasonably covered the risks. It’s something you can measure against to demonstrate value. The benchmark, and that gauge of success, is a security framework. It captures the experience and knowledge of security professionals from all over the world. It provides a road map to guide an organization through the maze of security issues.

This chapter covers the components of an IT security policy framework. It also helps you understand how to create a framework that meets your organization’s needs. The chapter covers the business and assurance consideration. The chapter also discusses the issues with unauthorized access and their ramifications. Through these discussions you learn better the value and construction of security frameworks.

Chapter 6 Topics

This chapter covers the following topics and concepts:

• What an IT security policy framework is

• What a program framework policy or charter is

• Which business factors you should consider when building a policy framework

• Which information assurance factors and objectives to consider

• Which information systems security factors to consider

• What best practices are for IT security policy framework creation

• What some case studies and examples of IT policy framework development are

Chapter 6 Goals

When you complete this chapter, you will be able to:

• Describe the role of a policy framework in an information security program

• Describe the different types of policies used to document a security program

• Describe what a dormant account is

• Explain the role of policies, standards, guidelines, and procedures

• Explain the organization of a typical standards and policies library

• Explain the personnel roles in a typical security department

• Explain what the C-I-A triad is and why it is important

What Is an IT Policy Framework?

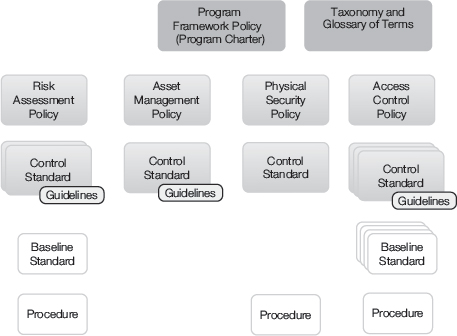

An IT policy framework includes policies, standards, baselines, procedures, guidelines, and taxonomy. Many frameworks resemble a hierarchy or tree. At the top of the tree is a charter or program framework policy, followed by additional policies. Then there are several standards. Under standards are many guidance and procedure documents. Getting the framework right is key to a successful security program.

Figure 6-1 offers one view of how you might structure an information security policy and standards library. For the framework to be useful, it must be accessible and understandable. While most frameworks are available online, it’s not enough just to provide access. It’s equally important to ensure the documents are written at a level that is well understood and can be navigated easily. The documents must be well organized, so that users can find what they are looking for quickly.

Building a policy framework is also like growing a tree. The roots and branches of the tree are established; you water the tree and allow it sufficient time to grow. Eventually it provides coverage for everyone. Over time, tree branches die off, leaves fall to the ground, new branches grow, and the tree needs pruning. A policy framework works in the same way. You give it ongoing attention to nurture the process and document content. This assures that it provides the coverage your organization needs and demands. What this means from a practical standpoint is that a policy framework does not have to be comprehensive on Day One. For example, you might have a policy that outlines the security requirements for managing encryption keys. As mobile technologies are introduced for the first time, these requirements may not provide adequate guidance or simply may not work with these new technologies. It may become clear that you need to create a separate mobile technology encryption policy.

FIGURE 6-1

A policy and standards library framework.

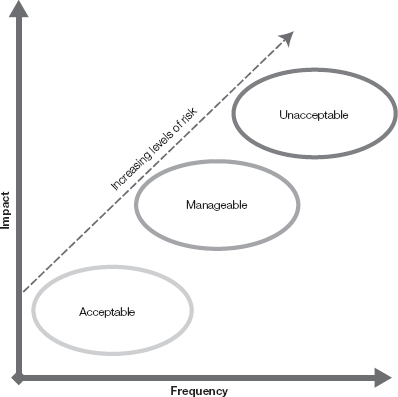

An organization’s security posture is often expressed in terms of risk appetite and risk tolerance. These two terms are sometimes misused and assumed to mean the same thing. They are not the same. While they both are used to measure how much risk an organization is willing to accept, they in fact have two very different purposes. Risk appetite generally refers to how much risk an organization is willing to accept to achieve its goal. This is often expressed by the impact on the organization and the likelihood of something bad happening. Figure 6-2 illustrates this point. Ideally you would like to face only risks in which the likelihood of the negative event is low, and even if it did happen, the impact to the organization would be minimal. But this is not an ideal world. Many security risks will have significant impact on customers and the profits of a business. These risks must be understood and managed.

Typically, the security risks are managed by adding controls. Eventually a set of risks becomes simply too great for an organization to accept. These risks may relate to life and safety, or their potential impact would put the organization out of business. A security framework must have policies that clearly draw the lines to define acceptable behavior that ensures activities fall within the limits of risk appetite. As the levels of risk increase, so must the level of controls.

Risk tolerance relates how much variance in the process an organization will accept. This is often expressed in term of a percentage, such as plus or minus 10 percent. For example, assume you own a company that buys, renovates, and sells real estate. Assume your company specializes in residential real estate. As a result, there may be no risk appetite for buying a commercial office building. That is because your company, lacking expertise in the commercial sector, is at greater risk of making a mistake if it tries to make a commercial deal. The higher costs of commercial properties and fluctuations in the market could result in huge losses that put your company out of business. Consequently, commercial properties may be outside your risk appetite. Within the residential properties you do control, you set a budget for renovations. You watch every dollar spent and put in controls to ensure you come in within 10 percent of budget. You’re comfortable that as long as you manage to this risk tolerance, you can make a healthy profit.

In an information security context, it’s not always clear when and how to apply these concepts. You cannot apply risk appetite and risk tolerance to every control. You must select those controls (or group of controls) where key risk decisions must be made. For example, consider the group of controls related to security patch management. A decision must be made balancing information security and business needs over how much risk will be accepted to allow systems to run without patches to close security vulnerabilities. A risk appetite may not allow any systems with critical patches to run in production beyond five days. This would address immediate threats, and there could be a risk tolerance of 30 days (plus or minus 10 percent) established for all remaining security patches to be applied.

What Is a Program Framework Policy or Charter?

The program framework policy, or information security program charter, is the capstone document for the information security program. The charter is a required document. This document establishes the information security program and its framework. This high-level policy defines:

• The program’s purpose and mission

• The program’s scope within the organization

• Assignment of responsibilities for program implementation

• Compliance management

FYI

The CISO may also be known by many other titles, depending upon the culture of the organization. The CISO role is functionally aligned to the top-ranking individual who has full-time responsibility for information security. Some examples include:

• Director of Information Security

• Chief Security Officer

• Director of Risk and Compliance

• Information Security Program Manager

The chief executive officer (CEO) usually approves and signs the charter. The charter establishes the responsibility for information security within the organization. It’s important that senior leadership of an organization express support for the information security program. This support comes in many forms. For instance, it’s not unusual for the CEO to attach a personal message to the release of an information security program charter, or as part of an annual information security awareness effort. This responsibility is often placed on an individual known as the chief information security officer (CISO). The CISO is responsible for the development of the framework for IT security policies, standards, and guidelines. The CISO also approves and issues these documents. One of the CISO’s primary roles is to ensure adherence to regulations. The regulations may be at the local, state, or federal level. The CISO also sets up a security awareness program. The program helps employees understand and live up to the organization’s information security policies, standards, guidelines, and procedures.

Information security teams must ensure that security policies comply with laws and regulations. However, information security personnel are not lawyers. They work with their organizations’ compliance and legal teams to gain an understanding of legal requirements. That is very different from determining whether an organization is violating a law. That is the task of the legal department—and if it’s not done properly there, the matter may be settled in court.

In other words, the information security team must determine violations of an organization’s security policy, but should never express an opinion on violations of law.

If a law appears to have been broken, a host of complex issues may arise, such as: What was the intent behind the actions taken? Was anyone’s behavior reckless?

It’s best for information security teams to express violations in terms of security policies. Information security leadership should ensure those policies comply with legal requirements. And there should be a process for reporting major violations to compliance and/or legal departments.

Purpose and Mission

This part of the policy states the purpose and mission of the program. You should define the goals of the IT security program and its management structure.

Integrity, availability, and confidentiality are common security-related needs. These needs can form the basis of the program’s goals. For example, most e-commerce systems maintain confidential personal data. In this case, the goals might include stronger protection against unauthorized disclosures.

You should create a structure that addresses alignment with program and organizational goals. Your policies should mirror your organization’s mission and goals. They should describe the operating and risk environment of the organization within this structure. Important issues for the structure of the information security program include:

• Management and coordination of security-related resources

• Interaction with diverse communities

• The ability to communicate issues of concern to upper management

Scope

A policy’s scope specifies what the program covers. This usually includes resources, information, and personnel. In some instances, a policy may name specific assets, such as major sites and large systems.

Sometimes, you must make tough management decisions when defining the scope of a program. For example, you may need to decide how the program applies to contractors who connect to your systems. The same concept applies to external organizations.

Responsibilities

A policy should state the responsibilities of personnel and departments related to the program. This includes the role of managers, users, and the IT organization. This is also referred to as the program’s delegation of authority.

Compliance

Compliance is the ability to reasonably ensure conformity and adherence to both internal and external policies, standards, procedures, laws, and regulations. A program-level policy should address enforcement of the policy. For example, what happens if someone doesn’t comply with computer security policies?

The program-level policy is a high-level document. It usually does not include penalties and disciplinary actions for specific infractions. However, this policy may authorize the creation of other policies or standards that describe violations and penalties. One common strategy for handling this issue is to have the information security policy refer to disciplinary procedures found elsewhere, such as in a human resources (HR) policy that broadly covers disciplinary actions.

Some organizations create a specific consequence model for information security policy violations. A consequence model does not replace the broader HR polices that deal with disciplining individuals. A consequence model is not intended to be punitive for the individual. Its purpose generally is to remove the risk introduced by the policy violation. For example, suppose a security policy has strict control requirements for coding applications that face the Internet. Assume an information security scan of a newly deployed interfacing application found a security weakness in direct violation of the policy. A consequence model (based on level of risk) could give the developer x days to fix the code to be compliance. The consequence of failing to fix the code within the prescribed time would be to take the application offline and remove the risk.

Industry-Standard Policy Frameworks

Policy frameworks provide industry-standard references for governing information security in an organization. They allow you to leverage the work of others to help jump-start your security program efforts. The following areas determine where framework policies are helpful:

• Areas where there is an advantage to the organization in having the issue addressed in a common manner, such as shared IT resources

• Areas that affect the entire organization, such as personnel security

• Areas for which organization-wide oversight is necessary, such as compliance

• Areas that, through organization-wide implementation, can result in significant economies of scale, such as unified desktop computer management

No two organizations are alike. For-profit companies may have different goals and concerns than nonprofit organizations or government agencies. Different needs require different solutions. Therefore, security professionals have a wide variety of policy frameworks to work with. It’s up to each organization to determine the best policy framework that meets the needs of the organization and the threats they face.

Three frameworks stand out because of their scope and wide acceptance within the security community:

• Control Objectives for Information and related Technology (COBIT)—A widely accepted set of documents that is commonly used as the basis for an information security program. COBIT is an initiative from ISACA, formerly known as the Information Systems Audit and Control Association, and is preferred among IT auditors.

• ISO/IEC 27000 series—An internationally adopted standard, the ISO/IEC 27000 series can be found in the information security management program of virtually any organization.

• National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publications, such as (SP) 800-53, “Recommended Security Controls for Federal Information Systems and Organizations”—Geared to U.S. government agencies and their subcontractors.

Many of the regulatory bodies use these standards to develop security guidance and auditing practices. By relying on those who have paved the way for you, you can help to assure compliance with regulations that affect your organization without reworking all of your compliance processes. The following sections offer details on how to use the ISO/IEC 27002 and NIST SP 800-53 standards to describe your policy framework.

ISO/IEC 27002 (2015)

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) develop and publish international standards. These standards are published as ISO/IEC numbered designations. It’s common to see these standards abbreviated as ISO. For example, the ISO/IEC 27002 standard is often shortened to ISO 27002.

ISO/IEC 27002 is titled “Information Technology–Security Techniques–Code of Practice for Information Security Management.” This is a popular industry standard for establishing and managing an IT security program. ISO/IEC 27002 outlines 15 main areas that compose the framework:

1. Foreword—Describes the overall purpose and key references for the document. This includes the following key areas:

• Scope

• Terms of reference

• Structure of the document

2. Information security policy—Describes how management should define an information security policy. Organizations usually maintain detailed security policies in a library. Information security standards, procedures, and guidelines support the library.

3. Organization of information security—Describes how to design and implement an information security governance structure. This section describes the need for an internal group that manages the program, including the governance of business partners.

4. Human resources security—Describes security aspects for employees joining, moving within, or leaving an organization. The organization should manage system access rights. The organization should also provide security awareness, training, and education. Section 4 covers these employment phases:

• Prior to employment

• During employment

• Termination or change of employment

5. Asset management—Describes inventory and classification of information assets. The organization should understand what information assets it holds, and manage their security appropriately. This section covers responsibility for assets and information classification.

6. Access control—Describes restriction of access rights to networks, systems, applications, functions, and data. This section addresses controlled logical access to IT systems, networks, and data to prevent unauthorized use. The following topics are covered:

• Business requirements for access control

• User access management

• User responsibilities

• Network access control

• Operating system access control

• Application and information access control

• Mobile computing and remote employee access

7. Cryptography—Describes the use and controls related to encryption. This includes the following key control areas:

• Cryptographic authentication

• Cryptographic key management

• Digital signatures

• Message Authentication

8. Physical and environmental security—Describes protection of computer facilities. Valuable IT equipment should be physically protected against malicious or accidental damage or loss, overheating, loss of main power, and so on. This section covers:

• Secure areas

• Equipment security

• Critical IT equipment, such as cabling and power supplies

9. Operations security—Describes operational management of controls to ensure that capacity is adequate and performance is delivered. This section includes these key topics:

• Operational procedures and responsibilities

• Protection against malicious and mobile code

• Backups

• Logging and monitoring

• Information systems audit coordination

10. Communications security—Describes securing the network and controlling access to information by third parties. This section includes these topics:

• Third-party service delivery management

• Network security management

11. Systems acquisition, development, and maintenance—Describes building security into applications. Information security must be taken into account in the Systems Development Life Cycle (SDLC) processes for specifying, building/acquiring, testing, implementing, and maintaining IT systems. These activities include the following:

• Security requirements of information systems

• Correct processing in application systems

• Cryptographic controls

• Security of system files

• Security in development and support processes

• Technical vulnerability management

12. Supplier relationships—Describes the policy and procedures needed to monitor suppliers’ information security controls. This includes but is not limited to:

• How suppliers access company information

• How suppliers access the company network

• Monitoring access and activity of suppliers when they are on the organization’s network

• Managing access rights when supplier personnel change roles

• Auditing suppliers to service level agreements

13. Information security incident management—Describes anticipating and responding appropriately to information security breaches. Information security events, incidents, and weaknesses should be promptly reported and properly managed. This section of the standard covers:

• Reporting information security events and weaknesses

• Managing information security incidents and improvements

14. Information security aspects of business continuity management—Describes protecting, maintaining, and recovering business-critical processes and systems. This section describes the relationship between IT disaster recovery planning, business continuity management, and contingency planning, ranging from analysis and documentation through regular exercising/testing of the plans. Controls are designed to minimize the impact of security incidents that occur despite the preventive controls from elsewhere in the standard.

15. Compliance—Describes areas for compliance, which include:

• Compliance with legal requirements

• Compliance with security policies and standards, and technical compliance

• Information systems audit considerations

ISO/IEC 27002 covers the three aspects of the information security management program: managerial, operational, and technical activities. All three must be present in any IT security program for comprehensive coverage. For more information about ISO/IEC 27002, visit http://www.iso27001security.com/html/27002.html.

NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-53

NIST is an agency of the U.S. Department of Commerce. NIST develops information security standards and guidelines for implementing them. NIST SP 800-53, “Recommended Security Controls for Federal Information Systems,” was written using a popular risk management approach. Organizations often rely on NIST publications for reference and to develop internal IT security management programs. NIST SP 800-53 uses a framework similar to ISO/IEC 27002. However, NIST SP 800-53 includes 18 areas that address managerial, operational, and technical controls. Table 6-1 summarizes NIST SP 800-53 rev. 4.

For more information about NIST SP 800-53, visit http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/PubsSPs.html

What Is a Policy?

Policies are an important part of an information security program. They are best defined as high-level statements, beliefs, goals, and objectives. Policies help protect an organization’s resources and guide employee behavior. Security policies help you address critical computer security issues. With effective policies in place, your organization will have better protection of systems and information.

Security policies also provide the “what” and “why” of security measures. Procedures and standards go on to describe the “how” of configuring security devices to implement the policy. The lack of information security policies and enforcement leaves an organization vulnerable to data breaches, business interruptions, and legal liabilities. In fact, in many states not having or not enforcing information security controls in accordance with industry norms could lead to jail time for business owners and executives. There’s a lot at stake. Yet, despite the urgent need and potential legal liabilities, many organizations do not have the defined security policies they need. According to a study in 2012 by Symantec of 1,015 small and mid-size companies in the U.S., 83 percent have no cybersecurity plan. Having a good set of security policies implemented can be major competitive advantage. It ensures the protection of customer information and the stability of the business systems, and protects the company from legal liabilities.

TABLE 6-1 A summary of NIST SP 800-53.

The IT security program begins with statements of management’s intentions. These intentions are documented as policies. Policies describe the following:

• Details of how the program runs

• Who is responsible for day-to-day work

• How training and awareness are conducted

• How compliance is handled

The following is an example of a high-level policy that establishes an IT security program:

Executive Management endorses the mission, charter, authority, and structure of Information Security. The Company’s Executive Management has charged Information Security with the responsibility for developing, maintaining, and communicating a comprehensive information security program to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of Company information resources.

Write policies as broad statements that describe the intent of management, defining the direction for the organization. Make these statements nonspecific as to how that will be accomplished. You should include details about how to meet the policy in a family of documents below the high-level policy.

What Are Standards?

You have many choices when deciding how to protect your computer assets. Some choices are based on quantifiable tradeoffs. Other choices involve conflicting tradeoffs and questions related to your organization’s strategic directions. When making these choices, the policies and standards you establish will be used as the basis for protecting your resources—both information and technology—and for guiding employee behavior.

Standards are formal documents that establish:

• Uniform criteria that you can evaluate and measure

• Methods to accomplish a goal

• Repeatable processes and practices for compliance to policies

Security standards provide guidance towards achieving specific security policies. Although security policies are written at a high level, there’s insufficient detail to explain how people should support them.

Security standards are often related to particular technologies or products. They are used as benchmarks for audit purposes and are derived from:

• Industry best practices

• Experience

• Business drivers

• Internal testing

Standards can come in different forms. Two common forms are: control or issue-specific standards and system-specific technical or baseline standards.

Issue-Specific or Control Standards

An issue-specific standard focuses on an area of current relevance and concern to your company. Be prepared for frequent revision of these standards because of changes in technology and other related factors. As new technologies develop, some issues diminish in importance while new ones continually appear. For example, it might be important to issue a standard on the proper use of a cutting-edge technology even if the security vulnerabilities are still unknown.

A useful structure for issue-specific or baseline standards is to break the document into basic components. Those components are described in the following sections.

Statement of an Issue. This section defines a security issue and any relevant terms, distinctions, and conditions. For example, an organization might want an issue-specific policy on the use of Internet access. The standard would define which Internet activities you permit and those you don’t permit. You may need to include other conditions, such as prohibiting Internet access using a personal dial-up connection from an employee’s desktop PC.

Statement of the Organization’s Position. This section should clearly state an organization’s position on the issue at hand. To continue with the example of Internet access, the policy should state which types of sites are prohibited. Examples of these sites may be pornography, brokerage, and/or gambling sites. The policy should also state whether further guidelines are available, and whether case-by-case exceptions may be granted, by whom, and on what basis.

Statement of Applicability. This section should clearly state where, how, when, to whom, and to what a particular policy applies. For example, a policy on Internet access may apply only to the organization’s on-site resources and employees and not to contractors with offices at other locations.

Definition of Roles and Responsibilities. This section assigns roles and responsibilities. Continuing with the Internet example, if the policy permits private Internet service provider (ISP) accesses with the appropriate approvals, identify the approving authority in the document. The office or department(s) responsible for compliance should also be named.

Compliance. Gives descriptions of the infractions that are unacceptable and states the corresponding penalties. Penalties must be consistent with your personnel policies and practices and need to be coordinated with appropriate management,

Points of Contact. This section lists the areas of the organization accountable for the policies’ implementation. These are typically the subject matter experts (SME). They interpret the policy. Often they are also in charge of ensuring the controls are in place to enforce the policy. It may also identify other applicable standards or guidelines. For some issues, the point of contact might be a line manager. For other issues, it might be a facility manager, technical support person, systems administrator, or security program representative.

System-Specific or Baseline Standards

A system-specific standard, or baseline standard, is focused on the secure configuration of a specific system, device, operating system, or application. Many security policy decisions apply only at the system level.

Examples include:

• Who is allowed to read or modify data in the system?

• Under what conditions can data be read or modified?

• What firewall ports and protocols are permitted?

• Are users allowed to access the corporate network from home or while traveling?

What Are Procedures?

A procedure is a written instruction on how to comply with a standard. A procedure documents a specific series of actions or operations that are executed in the same manner repeatedly. If properly followed, procedures obtain the same results under the same circumstances. Procedures support the policy framework and associated standards by codifying the steps that are proven to yield compliant systems. Procedures should be:

• Clear and unambiguous

• Repeatable

• Up to date

• Tested

• Documented

Examples of procedures include:

• Incident reporting

• Incident management

• User ID addition/removal

• Server configuration

• Server backup

• Emergency evacuation

A single standard often requires multiple procedures to support it. The people responsible for supporting or operating technical equipment in compliance with a standard are often the same people who document procedures to meet compliance requirements. Security department personnel may assist with documenting procedures. Once approved, the procedures are published within the policy and standards library with appropriate controls over who has access to them. Procedures are usually where metrics are collected to monitor compliance. Consequently, it’s important to understand how these new procedures impact any governance and oversight. For example, assume there’s a weekly oversight meeting to review the volume of user ID changes such as adding and deleting accounts. Also assume there’s a dashboard that breaks down weekly activity to itemize the types of changes that occurred. This type of dashboard is common to try to proactively identify problem areas and detect unusual activity. A new procedure may be introduced to remove dormant accounts. A dormant account is typically one that has not been used for an extended period of time. When this new procedure was put in place to remove dormant accounts, it would directly impact the weekly oversight meeting. In other words, not only do you need to implement the new security procedure but also update the weekly dashboard. Additionally, you need to discuss with the members of the weekly oversight meeting the ramification of the process change made.

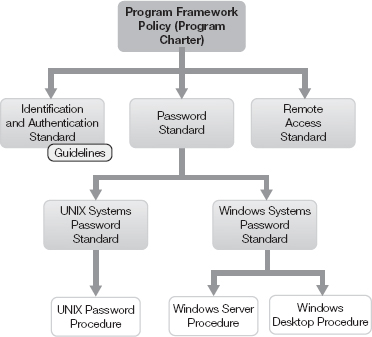

Figure 6-3 illustrates an example of an extract of a policy and standards library. The figure highlights an access control policy, which is one of many security-related policies.

Exceptions to Standards

Situations arise in which your organization cannot meet one or more standards immediately. You must recognize an exception to standards to determine where problems may exist.

Periodic reviews of these exceptions can also lead to improvements to the standards when many exceptions point to a general inability to meet compliance goals. Paying attention to exceptions is vital to ensuring that the policy framework remains relevant and current.

FIGURE 6-3

A possible access control policy branch of a policy and standards library.

Exceptions are seldom approved “forever.” Typically, they are reexamined annually. This allows leadership to discuss whether they are willing to accept the risk for another year or fund the changes needed to ensure compliance with security policies. Exceptions often include a discussion of compensating controls and mitigating controls. Compensating controls mean that while you cannot meet the letter of the policies you can still achieve their goals through other means. Mitigating controls mean that while you cannot meet all the policies’ goals, you can still achieve partial compliance. It’s important to understand when you are approving a security exception how much risk you are accepting.

What Are Guidelines?

IT security managers often prepare guidelines, or guidance documents, to help interpret a policy or a standard. Guidelines may also present current thinking on a specific topic. Guidelines are generally not mandatory—failing to follow them explicitly does not lead to compliance issues. Rather, guidelines assist people in developing procedures or processes with best practices that other people have found useful. A guideline can also clarify issues or problems that have arisen after the publication of a standard.

You can think of guidelines as “standards in waiting.” They are used where possible, and feedback on guidelines is given to IT security managers responsible for policy and standards maintenance. Guidelines provide the people who implement standards or baselines more detailed information and guidance (hints, tips, processes, etc.) to aid in compliance. These documents are optional in a library but are often helpful.

Eventually, a guideline may become a standard when its adoption is widely accepted and implemented. For example, assume you have guidelines outlining five acceptable encryption techniques. Of the five, assume three become so widely adopted by the development teams that they are used in 95 percent of all applications. A decision could be made to make those three the standard for all new development. You can then treat the other two techniques, used in 5 percent of the application, as exceptions; or you can budget to upgrade them.

![]() TIP

TIP

Joining an association focused on IT security is a good way to meet peers and develop skills. There are many associations you can join, including ISACA (isaca.org), ISC2 (ISC2.org), and ISSA (issa.org).

Business Considerations for the Framework

An organization’s collection of security policies, and therefore the entire security framework, shows its commitment to protecting information.

As with security policies in general, a couple of considerations for implementing a framework are:

• Cost—Cost of implementing and maintaining the framework

• Impact—Impact of the controls required by the framework on employees, customers, and business processes

Creating a policy framework from the ground up takes time and effort. It’s important for management to budget for these expenses. In addition, as the number of documents in the framework grows, you may need a content management system to manage the documents. Many organizations already use Microsoft SharePoint Server or a similar product to manage all business-related documents. You can use the same system to manage documents in a policy framework.

Employees often resist change, especially changes that affect how they need to perform their jobs. However, a comprehensive policy framework can help employees do their jobs more efficiently. The framework includes guidelines that employees can follow, and procedures that specify how to perform tasks. Essentially, a policy framework provides a structure within which employees can work more efficiently.

Adding a taxonomy and glossary of terms is critically important. A well-formed taxonomy becomes the “Rosetta stone” for the framework’s policy documents. It’s used to interpret the meaning of the policies and scope efforts. Let’s assume your policies include the terms platform and network infrastructure. What does platform mean?

Complying with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act

As technology further expands, laws and regulations eventually follow to compel positive action to protect information systems.

In 2002, the U.S. Senate passed the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Act, which gained the attention of U.S. corporate CEOs. The act passed in the wake of the collapse of Enron, Arthur Andersen, WorldCom, and several other large firms. SOX requires publicly traded companies to maintain internal controls. The controls ensure the integrity of financial statements to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and shareholders. The act also requires that CEOs attest to the integrity of financial statements to the SEC.

Because of this mandate, controls related to information processing and management are now highly scrutinized. Since the law took effect, the need for a comprehensive library of current operating documents is underscored.

Do platform requirements include a firewall? Maybe. Maybe not. Yes, a firewall sits on a platform. There’s a physical box with an operating system. But the taxonomy and glossary of terms may define platform as devices upon which an application resides, such as application and database servers. All other non-application networked devices may fall under the definition of network infrastructure. In this case, for firewall controls, you would go to the framework’s network infrastructure documents. This distinction is not academic. Most likely the control requirements for platforms would be different from those for network infrastructure. And it is critically important to get the right controls for the different devices.

A policy framework also helps management adhere to compliance requirements. Your security policy framework enables you to show regulators that you are using best practices. Many regulations provide specific details that must be included in your security policies. It’s often helpful to create a “cheat sheet” that cross-references your security documents with the standards. For example, an entry might state that “HR Policy 2010-033 entitled ‘Pre-Employment Screening’ satisfies PCI DSS requirement 12.7.” This will come in very handy if you are ever audited; you can use the cheat sheet to show auditors the exact sections of policy that implement each requirement. The challenge is maintaining these cheat sheets. It’s important to build in a process of updating the cheat sheets anytime you revise the policies they’re based on.

Roles for Policy and Standards Development and Compliance

Developing and maintaining a policy framework is a major undertaking. In large organizations, it usually requires many people. Table 6-2 lists roles commonly found in the development, maintenance, and compliance efforts related to a policy and standards library.

Information Assurance Considerations

To develop a comprehensive set of security policies, start with the goals of information security: confidentiality, integrity, and availability. Information assurance (IA) tenets also include nonrepudiation and authentication.

One of the prime objectives of the information security program is to assure that information is protected. Ensuring confidentiality means limiting access to information to authorized users only. The integrity of the information must also be maintained so that it can be trusted for decision-making. A system is considered to have integrity when you can trust that any modifications to the data were intentional changes made by authorized users or business processes. Availability ensures the information is accessible to authorized users when required. Nonrepudiation ensures that an individual cannot deny or dispute being part of a transaction. Finally, authentication is the ability to verify the identity of a user or device.

TABLE 6-2 Roles related to a policy and standards library.

| ROLE | ACTIVITY |

| CISO | Establishes and maintains security and risk management programs for information resources |

| Information resources manager | Maintains policies and procedures that provide for security and risk management of information resources |

| Information resources security officer | Directs policies and procedures designed to protect information resources; identifies vulnerabilities, develops security awareness program |

| Owners of information resources | Responsible for carrying out the program that uses the resources. This does not imply personal ownership. These individuals may be regarded as program managers or delegates for the owner. |

| Custodians of information resources | Provide technical facilities, data processing, and other support services to owners and users of information resources |

| Technical managers (network and system administrators) | Provide technical support for security of information resources |

| Internal auditors | Conduct periodic risk-based reviews to ensure the effectiveness of information resources security policies and procedures |

| Control partners | Typically in areas such as compliance and operational risk. Ensure that security policies result in operational compliance with risk appetite and regulatory requirements. |

| Users | Have access to information resources in accordance with the owner-defined controls and access rules |

FYI

The goals of information security—confidentiality, integrity, and availability—are often referred to as the C-I-A triad. Some systems security professionals refer to this as the “A-I-C” triad (availability, integrity, and confidentiality) to avoid confusion with the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, which is commonly referred to as the CIA. Either abbreviation is acceptable. However, if you use C-I-A, make sure people understand you’re referring to “confidentiality, integrity, and availability.”

To meet information assurance needs, your framework should include policies for the following:

• Automation of security controls, where possible.

• Implementation of appropriate accounting and other integrity controls.

• Controls that handle potential conditions that appear while a system is operating. This should include error handling that won’t reduce the normal security levels it’s expected to support. Fail-secure rather than fail-safe is better for protecting information systems.

• Development of systems that detect and thwart attempts to perform unauthorized activity.

• Assurance of a level of uptime of all systems.

The following sections address the tenets of IA from a policy framework perspective.

Confidentiality

Confidentially broadly means limiting disclosure of information to authorized individuals. This could include protecting the privacy of personal data and proprietary information. To meet confidentiality requirements, your security objectives must be specific, concrete, and well defined. Consider the goal of confidentiality as applied to e-mail as an example. You might have an objective of ensuring that all sensitive information is protected against eavesdropping. You implement this by requiring that users encrypt all e-mails containing sensitive information and ensuring that only authorized individuals have access to the key to decrypt the messages.

Write objectives so they are clear and achievable. Security objectives should consist of a series of statements that describe meaningful actions about specific resources. These objectives are often based on meeting business functions. In addition, they should state the security actions needed to support the requirements.

Integrity

Integrity refers to guarding against improper modification or destruction of data. One way to meet integrity requirements is to define operational policies that list the rules for operating a system. Access control rules in the form of permissions are often used to achieve this goal. Integrity can be achieved by limiting the type of permission to only certain accounts. For example, you might have a file that is widely accessible to read but that only a few individuals have permission to modify.

Managers must make decisions when developing policies because it is unlikely that all security objectives will be fully met. Consider the degree of granularity needed for operational security policies. Granularity indicates how specific the policy is regarding resources or rules. The more granular the policy, the easier it is to enforce and to detect violations. A more granular policy involves security controls over a specific element of technology. It might describe all the settings needed to configure a device or system securely. Checking it only requires ensuring that the settings are still in place. A less granular policy does not provide many details about a specific control, which allows people to determine how to comply. With less granular policies, it’s more difficult to prove compliance, because each situation differs.

It’s important to find and maintain the right level of granularity in security policies. The advantage of less granular policies is that they can be applied to broad sets of circumstances. Yes, they are subject to more interpretation. But when unknown conditions arise, they can be used broadly to control emerging risks. In contrast, very granular policies most likely will not address emerging risks precisely. They may be less helpful users trying to figure how to deal with new threats.

A formal policy is published as a distinct policy document. A less formal policy may be written in a memo. An informal policy might not be written at all. Unwritten policies are extremely difficult to follow or enforce. On the other hand, very granular and formal policies are an administrative burden. In general, best practice suggests a granular formal statement of access privileges for a system because of its complexity and importance.

Availability

Availability is the timely and reliable accessibility of information. To meet requirements for availability, your policy framework may include documents specifying when and how systems must be accessible to internal and external users. This can lead to different solutions for different needs. For example, external users require different forms of access than internal users. An external user might be required to use a virtual private network (VPN), for instance, to access the internal network.

Information Systems Security Considerations

The success of an information security program depends on the policy produced and on the attitude of company management toward securing information IT systems. The policy framework helps ensure that all aspects of information security are considered and controls are developed. As a policymaker, it’s up to you to set the tone and the emphasis on the importance of information security.

Unauthorized Access to and Use of the System

The proliferation of technology has revolutionized the ways information resources are managed and controlled. Long gone are the days of the “Glass House,” full of mainframe computers under tight centralized control. Internal controls from yesteryear are inadequate in controlling today’s decentralized information systems. Relying on poorly controlled information systems brings serious consequences, including:

• An inability of the organization to meet its objectives

• An inability to service customers

• Waste, loss, misuse, or misappropriation of scarce resources

• Loss of reputation or embarrassment to the organization

To avoid these consequences, risk management approaches are needed. Risk is an accepted part of doing business. Risk management is the process of reducing risk to an acceptable level. You can reduce or eliminate risk by modifying operations or by employing control mechanisms.

The dollars spent for security measures to control or contain losses should never be more than the estimated dollar loss if something goes wrong. Balancing reduced risk with the costs of implementing controls results in cost-effective security. The greater the value of information assets, or the more severe the consequences if something goes wrong, the greater the need for control measures to protect it.

Unauthorized Disclosure of the Information

Maintaining the confidentiality of information is critical to many organizations in the age of knowledge workers. When you consider the economic activity of the world’s more advanced nations, most of the productive output of workers is information, rather than the widgets of yesterday. Consider two examples:

• Market research companies spend thousands of dollars and countless hours gathering business intelligence for their clients. Often, the sole output of these projects is a report summarizing the results. If this got into the hands of the client’s competitors, it would destroy the competitive advantage created by the report. It could also reduce the economic value of the information to the client, and potentially jeopardize the market research firm’s client relationship.

• Manufacturing companies may now produce many of their products in overseas factories where labor is inexpensive. However, they still do the “knowledge work” of developing product plans, formulas, and other trade secrets in developed nations. If those plans got into the hands of competitors, it would be quite simple for the competitor to ship the plans to an overseas factory and produce the same product without any of the research and development expense.

Disruption of the System or Services

The demands for timely and voluminous information are increasing. One major protection issue is the availability of information resources. In some cases, service disruptions of even a few hours are unacceptable. Think about how much revenue Amazon.com or eBay.com loses for every hour of downtime. Reliance on essential systems requires a plan for restoring systems in the event of disruption. Organizations must first assess the potential consequences of an inability to provide their services and then create a plan to assure availability.

If information is modified by any means other than the intentional actions of an authorized user or business process, it could spell disaster for the business. This underscores the importance of integrity controls, which prevent the inadvertent or malicious modification of information. Consider, for example, a product-testing firm that spends many hours testing the optimal settings for a piece of safety equipment used in factories. If a power surge alters the data stored in the testing database, the company might use the incorrect data to recommend equipment settings, jeopardizing the safety of factory workers.

Destruction of Information Resources

In addition to unauthorized modification of information, security controls should also protect against the outright destruction of information, whether intentional or accidental. The most common control used to protect against this type of attack is the system backup. By storing copies of data on backup tapes or other media, the company has a fallback option in the event data is destroyed. Consider the case of an insurance company that stores policy information on servers in a data center. If that data center is destroyed by fire, off-site backup tapes can be used to re-create it. Without those backup tapes, the company would have no way of knowing which policies it had issued, putting the entire business in jeopardy.

Best Practices for IT Security Policy Framework Creation

Your policies need high visibility to be effective. When implementing policies, you can use various methods to spread the word throughout your organization.

Use management presentations, videos, panel discussions, guest speakers, road shows, summits, question/answer forums, and newsletters. Introduce computer security policies in a manner that ensures that management’s support is clear, especially where employees feel overwhelmed with policies, directives, guidelines, and procedures.

Remember that the work of building awareness and gaining acceptance of security policies does not start when the framework is published. Its success will be determined by how it is put together and who is involved. Every organization is different, and differences play out in many ways. Organizations vary as to their industry or field, their regulatory requirements, their culture, and their leadership personalities.

All are necessary considerations as you start to develop a framework. In general, you should state core principles in form of goals upfront. This defines “what” the framework must achieve. These goals are typically nonnegotiable security requirements. First get buy-in on the “what,” and then get others to work together with you on the “how.” You can be more flexible on the “how” than the “what.” Gain ownership from key user groups by offering them choices on how to achieve policy goals. Executives and end users know the business and can usually finds ways to integrate security processes while minimizing operational impact.

Formulating viable computer security policies is a challenge and requires communication and understanding of the organizational goals and potential benefits that will be derived from policies. Through a carefully structured approach to policy development, you can achieve a coherent set of policies. Without these, there’s little hope for any successful information security systems.

Case Studies in Policy Framework Development

This section provides three case studies that help you understand how to develop or implement a policy framework. You will look at cases from the private sector, the public sector, and the critical infrastructure protection area.

Private Sector Case Study

In 2008, Nadia Fahim-Koster, director of Piedmont Healthcare IT Security, reassessed the security compliance of the hospital using a well-established approach. The director decided to start with baseline metrics for IT security risk. This would help her determine whether the systems were already in compliance. It would also provide a baseline when assessing systems in the future. If systems were not in compliance, her IT team could adjust security configurations and controls to bring them into compliance. However, the director faced the following challenges:

• A large, diverse network of systems with over 7,000 devices

• An incomplete inventory of IT assets and their configurations

• No easy way to classify assets

• A broad Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) standard that left elements of reporting open to interpretation

She assembled an IT team to work on the project. They began with asset discovery to create a complete and up-to-date inventory of systems. Next, they looked at system configurations to determine if they complied with regulations and existing hospital policies.

The director decided to measure Piedmont Healthcare’s IT security controls using NIST SP 800-53. The team established a framework for classifying and measuring security controls across the Piedmont Healthcare network.

“Selecting the NIST framework as our measurement framework meant that we had to classify all of our IT assets the same way,” explained Fahim-Koster. “Once this was completed, we could begin to capture the existing security controls and perform a gap analysis to see where we needed to make improvements.”

Using the NIST framework, Piedmont classified its servers as high, medium, or low impact based on the type of information they contained. When IT personnel determined the gaps in compliance controls, they could prioritize which servers to address first and prioritize which controls to use.

In 2006, the State of Tennessee determined the need for a comprehensive information security program. One of the main goals was to protect the state’s revenues, resources, and reputation. The state accomplished this by researching, selecting, and implementing risk management methodologies, security architectures, control frameworks, and security policies.

The policies for Tennessee were based on the ISO/IEC 17799 (now ISO/IEC 27002) standard framework. The policies comply with applicable laws and regulations. The policies in the framework are considered the minimum requirements to provide a secure computing operation for the state.

The framework defines the information security policies for the State of Tennessee and the organizational structure required to communicate, implement, and support these policies. The policy framework was developed to establish and uphold the controls needed to protect information resources against unavailability, unauthorized or unintentional access, modification, destruction, or disclosure.

The policies and framework cover any information asset owned, leased, or controlled by the State of Tennessee. They control the practices of external parties that need access to the State of Tennessee’s information resources. The policies were developed to protect:

• All state-owned desktop computing systems, servers, data storage devices, and mobile devices

• All state-owned communication systems, firewalls, routers, switches, and hubs

• Any computing platforms, operating system software, middleware, or application software under the control of third parties that connect to the State of Tennessee’s computing or telecommunications network

• All data stored on the State of Tennessee’s computing platforms and/or transferred by the state’s networks

Private Sector Case Study

Target is a major retailer, with 1,797 stores in the U.S. and 127 in Canada. Target employs over 360,000 people. Since 1962 it has built its reputation as a trusted member of many communities. It’s hard to imagine there’s anyone who grew up in the United States who doesn’t recognize the brand or hasn’t shopped at Target.

In December 2013, during a very heavy Christmas selling season, the retailer announced that a data breach had occurred. It included the theft of about 40 million credit card records. Additionally, the breach resulted in theft of 70 million records containing personal information such as addresses and phone numbers. The cause of the breach was linked to a vendor who had access to Target’s network, through which point of sale (POS) devices were infected with malware. The malware was on thousands of POS systems for weeks. This was one of the largest retail data breaches of its kind.

When the breach was revealed on December 19, the company’s stock dropped 11 percent. The stock price largely rebounded within a few months, but the retailer is still feeling the impact. In February 2014, Target reported it had incurred $61 million in costs related to the breach. In March 2014 the CIO resigned, and Target announced it would hire a new CIO and, for the first time, a dedicated CSO. Additionally, in March 2014 news stories outlined a lawsuit against Target Corporation and Trustwave Holdings Inc., which provides credit card security services to Target. Two banks are suing for “monumental” losses. Some estimate that the losses could exceed $1 billion for card issuers and $18 billion for banks and retailers combined.

The stakes are high in the case of such a breach. It may put the very survival of a small or midsize company at risk. Even for a large company, the financial impact can be significant. Most important is the impact on the customer. It may be felt for years, given the potential for identity theft and credit problems.

The public may never know exactly what led to the breach. What is known is that there were serious weaknesses in the information security framework and related controls. Take a look at three major impact areas that a security framework, if well implemented, should have been addressed:

1. The lack of a dedicated CSO

2. Lack of vendor access management

3. Lack of network POS controls

With no dedicated chief security officer, information security leadership responsibility was spread around the organization, with the CIO responsible for execution.

This lack of a dedicated CSO created an inherent conflict of interest. The CIO in effect had to wear two hats: one to deliver the latest technology to drive sales throughout the store, and the other to protect the security interests of the customers and the company. All CIOs have this challenge of balance. The difference is that within a large organization, the CSO has a seat at the executive table and can challenge CIO decisions. Full-time CSOs can immerse themselves in the information security discipline. That includes gaining a deeper appreciation of emerging security risks than a CIO can typically achieve.

Vendor access must be properly managed if it is to be limited and monitored. If in fact a vendor was the source of the malware infection of the POS network, that indicates a failure to manage vendors and their access. In an ideal world, the breach of a vendor system or account should not lead to a breach of an organization’s systems. These accounts and connection should be highly controlled. At a minimum, such a breach should be detected and stopped from spreading. But neither preventive nor detective controls seemed to work in this case.

It’s fair to conclude that the network for the POS devices was not segmented effectively. Effective segmentation would have offered several key advantages. It limits access to the devices, which reduces the likelihood of malware infection in the first place. It allows a network to be purpose built, meaning that traffic can be more closely monitored to detect unusual activity such as that of malware. Segmentation also limits egress traffic. This means that even when a malware infection occurs, the information it captures cannot leave the network. This layered security approach using segmentation provides a strong security control.

The public may never know for sure what happened in the case of the Target breach. But it’s clear that these controls, which are part most large-company security frameworks, either did not exist or were not effectively implemented.

![]() CHAPTER SUMMARY

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Policy framework development is needed for the establishment and ongoing operation of the organization’s security program. It establishes the top leadership’s intent as to how information security should be managed. This program begins with documentation in the form of policies, standards, baselines, procedures, and guidance for compliance. The library of documents is arranged as a hierarchy with the highest level consisting of a charter. The next level includes policies, followed by an increasing number of standard and baseline documents. These documents are supplemented with guidelines to aid in implementation. Finally, many procedure documents that explicitly describe how to implement a security control or process are included. The library should be developed and managed by dedicated personnel who are experts in the subject matter related to the organization’s industry or mission.

Any effective IT security program includes top-down sponsorship to establish and enforce these policies and standards. This framework of documents identifies how an organization manages security risk within its risk appetite and risk tolerance. Because information security never stands still for long, most of the documents in a policy and standards library must be considered living documents that are updated as technology and the environment changes.

Compliance

Dormant account

Exception

Granularity

Information security program charter

ISO/IEC 27000 series

Issue-specific standard

IT policy framework

NIST SP 800-53

Risk appetite

System-specific standard

![]() CHAPTER 6 ASSESSMENT

CHAPTER 6 ASSESSMENT

1. An IT policy framework charter includes which of the following?

A. The program’s purpose and mission

B. The program’s scope within the organization

C. Assignment of responsibilities for program implementation

D. Compliance management

E. A, B, and C only

F. A, B, C, and D

2. Which of the following is the first step in establishing an information security program?

A. Adoption of an information security policy framework or charter

B. Development and implementation of an information security standards manual

C. Development of a security awareness-training program for employees

D. Purchase of security access control software

3. Which of the following are generally accepted and widely used policy frameworks? (Select three.)

A. COBIT

B. ISO/IEC 27002

C. NIST SP 800-53

D. NIPP

4. Security policies provide the “what” and “why” of security measures.

A. True

B. False

5. ________ are best defined as high-level statements, beliefs, goals, and objectives.

6. Which of the following is not mandatory?

A. Standard

B. Guideline

C. Procedure

D. Baseline

7. Which of the following includes all of the detailed actions and tasks that personnel are required to follow?

A. Standard

B. Guideline

C. Procedure

D. Baseline

8. Accounts that have not been accessed for a extended period of time are often referred to as ________.

9. List the five tenets of information assurance that you should consider when building an IT policy framework. ________

10. The purpose of a consequence model is to discipline an employee in order to ensure future compliance with information security policies.

A. True

B. False

11. When building a policy framework, which of the following information systems factors should be considered?

A. Unauthorized access to and use of the system

B. Unauthorized disclosure of information

C. Disruption of the system

D. Modification of information

E. Destruction of information resources

F. A, B, and E only

G. A, B, C, D, and E

12. What is the difference between risk appetite and risk tolerance?

A. Risk tolerance measures impact and likelihood, while risk appetite measures variance from a target goal.

B. Risk appetite measures impact and likelihood, while risk tolerance measures variance from a target goal.

C. There is no difference between these two.

13. A mitigating control eliminates the risk by achieving the policy goal in a different way.

A. True

B. False