|

12 |

Incident Response Team (IRT) Policies |

NO MATTER HOW WELL YOUR DATA is protected, eventually there will be a breach of security or a natural disaster. It could be the result of a human error. It could be the result of a configuration error. It could be the result of an operating system vulnerability or a host of problems outside your control. No information security program is perfect. What is certain is that at some point, most organizations will have to respond to a security incident. The speed and effectiveness of the response will limit the damage and reduce any losses. When an incident occurs, an organization needs to respond quickly through a well-thought-out process. An effective response can control the costs and consequences resulting from the incident.

Fortunately, day-to-day responding to security events does not typically rise to the level of a recovery event. However, security events do have the potential to create outages that require activation of a business continuity plan. Whether this activation is due to a security event or natural disaster, security response teams need to be aware of how recovery plans are built and executed.

Well-prepared organizations create an incident response team (IRT). This team and its supporting policies ensure that an incident is quickly identified and contained. It’s also the IRT’s responsibility to perform a careful analysis of the cause of the incident. Understanding the nature of an incident can help prevent future attacks. An IRT is the first responder to major security incidents within an organization. It’s not unusual for an attack to be active when the team responds. To ensure the IRT members are effective at what they do, the organization needs to provide the policies, tools, and training necessary for their success.

This chapter will focus on the Incident Response Team. It will define an incident and related policies. It will discuss how to create an IRT. It will discuss various roles and responsibilities within an IRT. The chapter will examine key activities that are performed during an incident. It will also discuss specific policies and procedures ranging from reporting and containing to analyzing an incident.

Additionally, this chapter will look at key aspects and documents related to disaster recovery and business continuity. This understanding is high level and foundational in the event a security incident triggers the activation of a recovery plan. Finally, the chapter will review best practices and explore some case studies.

Chapter 12 Topics

This chapter covers the following topics and concepts:

• What an incident response policy is

• How to classify incidents

• What a response team charter is

• Who makes up an incident response team (IRT)

• Who is responsible for actions during an incident

• Which procedures must be followed to respond to an incident

• What best practices to follow for incident response policies

• What business impact analysis (BIA) policies are

• How business continuity plan (BCP) policies protect information

• How disaster recovery plan (DRP) policies protect information

• What some case studies and examples of incident response policies are

Chapter 12 Goals

When you complete this chapter, you will be able to:

• Explain the purpose of an incident response policy

• Define what an incident is

• Explain various incident classification methods

• Understand key components of an IRT charter

• Describe IRT member roles and responsibilities

• Understand major procedures for responding to an incident

• Explain best practices for incident response

• Apply knowledge learned in case studies to real-world issues

• Describe a BIA, a BCP, and a DRP

• Describe the relationship between a BIA, a BCP, and a DRP

An incident response team (IRT) is a specialized group of people whose purpose is to respond to major incidents. The IRT is typically a cross-functional team. This means the people on the team have different skills. They are pulled together in a coordinated effort. In many organizations, the IRT is formed to respond to major incidents only. Minor incidents are often managed as part of normal operations. When the team is called together, the IRT is said to be “activated.”

It would not be practical to activate the IRT for minor incidents. Policy infractions, for example, are handled by an individual’s manager. Suppose an employee shares his or her password with a second employee. This might occur when that second employee has been approved but is waiting for access to be granted. An incident report may be required in this case but the IRT would not be activated.

The incident response policy must be clear and concise to prevent ambiguity in the response process. The policy must define what an incident is versus an infraction. The policy must define the criteria for activating the IRT. There should be a centralized incident notification process so that appropriate individuals are aware of incidents. These individuals can then make a determination whether to declare a disaster. Most important, the policy and related processes must enable the IRT to respond to incidents quickly. From the point an incident is detected to the point the IRT is activated, as little time should pass as possible. Organizations cannot afford to be slow to respond to an active attack.

There are many types of security incidents. When to declare an incident and activate an IRT depends on the organization’s policy. This chapter focuses on major information security breaches. Major breaches can include incidents such as systems breached from the outside, internal fraud, or a denial of service attack.

What Is an Incident?

An incident is any event that violates an organization’s security policies. An incident may disrupt normal operations of an application, system, or network. An incident may result in a reduction in quality of service and in service outages. These outages may require the activation of a recovery plan. An incident may also result in unauthorized access to or modification of data. Examples of security incidents include:

• Unauthorized access to any computer system

• A deliberately caused server crash

• Copying customer information from a database

• Unauthorized use of computer systems for gaming

It is important that a formal incident definition is included in the incident response policy. This definition is then used to support processes for declaring an incident and activating the IRT.

Incident Classification

The classification of incidents is part of the security policy. The classification approach can be documented as an incident response policy or a standard. By definition, if you have an incident, a weakness in your security has been exploited. By classifying the incident you can better understand the threat and the weakness. Knowing the type of attack can help you determine how to respond to stop the damage. It can also help you analyze the control weaknesses in your environment. This helps reduce the risk of future attacks. There’s no one standard approach to follow in classifying incidents. However, an industry often adopts similar approaches among companies. The key point is to select an approach that meets your legal and regulatory obligations. This should be an approach that provides sufficient detail to analyze an incident. This analysis will help you improve weaknesses that lead to incidents.

As an example, Visa requires its merchants to report security incidents involving cardholder data. This report should be issued whenever a breach is detected that violates the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS). One method of classifying a breach is by attack method. Visa issued examples of these attack vectors in a guidance document in May 2011. The following are examples of attack vectors that Visa identified as methods to gain unauthorized access to systems and sensitive information:

• SQL injection—A technique that allows the alteration of user-supplied input fields that an application uses to build a SQL query.

• Improperly segmented network environment—Related attacks rely on the lack of partitioning or on isolating high-risk assets on their own network segments. For example, in a flat network all portions of the network are accessible from anywhere on the network. A breach in one part of the network exposes the entire network to potential access.

• Malicious code or malware—Programs (such as viruses, worms, Trojan applications, and scripts) added to the platform without a user’s knowledge. These programs can be used to gain privileged access, capture passwords and other confidential information, and destroy or disrupt services.

• Insecure remote access—Attacks gaining access through remote services such as point-of sale (POS) devices, vendor networks, and employee remote access tools.

• Insecure wireless—Attacks accessing the network through wireless points of entry. The wide variety of networked devices that are now wireless ready has increased the risk in recent years. Such devices include copiers, fax machines, inventory systems, POS terminals, IP cameras, and more.

Another example is the federal government. Under the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA), the government uses the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication 800-61. This publication classifies incidents into the following events on a system or network:

• Malicious code—Code that rapidly infects other machines

• Denial of service—An attacker crafting packets to cause networks and/or computers to crash

• Unauthorized access—An exploit to gain access

• Inappropriate usage—Unacceptable use of the computer, such as copying illegal software or inappropriate statements in e-mail

It’s important to use a classification that has meaning to both internal and external stakeholders. In both the Visa and FISMA approaches, incidents must be reported. These breaches are classified within categories that help assess the threat level. Also, they use a taxonomy, or classification system, that is easily understood by external stakeholders. It’s not uncommon to find similarities among many incident-classification approaches. They all share the goal of providing a common language to describe security incidents.

The incident classification is also used to assess the severity of the incident. That is, is an incident minor or major? On this basis, you determine whether the IRT should be activated. What is considered a major incident versus a minor one depends on the organization’s view of risk. Major incidents are generally viewed as incidents that have significant impact on the organization. The impact can be measured in several ways. It might be financial. It may be measured with regard to disruption of service or legal liability. From a practical standpoint, many major incidents are easier than minor incidents to identify. They might cause effects such as a significant number of users unable to process transactions or unauthorized access to millions of customers’ personal data. Any incident related to the protection of human life is considered a major incident. What is considered a minor incident depends on how much risk the organization is willing to accept.

FYI

Incidents can turn into court cases. It’s important that the actions of the IRT be clear and show reasonable due care. Due care refers to the effort made to avoid harm to another party. It’s a legal term that essentially refers to the level of care that a person would reasonably be expected to exercise under particular circumstances. All documents produced during an incident should be written in a straightforward, professional manner.

Typically, organizations require a charter before an IRT can be formed. A charter is an organizational document that outlines the mission, goals, and authority of a team or committee. It’s important that legal review the IRT charter for any language that might create a liability. Always assume an outside party may eventually view the charter.

The first step in writing a charter is to determine the type of IRT model to adopt. This part of the charter determines the authority, approach, and deliverable of the IRT. There several types of IRT models:

• IRT provides on-site response—The IRT has full authority to contain the breach.

• IRT acts in a support role—The IRT provides technical assistance to local teams on how to contain the breach.

• IRT acts in a coordination role—The IRT coordinates among several local teams on how to contain the breach.

Many IRTs provide on-site response. In this case, the IRT is given complete authority to contain the threat. This typically means an IRT member is on-site with hands on the keyboard providing technical response. This IRT model requires its members to have full authority to direct local resources. The IRT members make key decisions in consultation with upper management. The IRT members may be required to have a specific local expert execute a task. However, the expert executes the task under the direction of the IRT member.

When the IRT is in a support role, its members become a resource for the local team. The local team has the responsibility to respond to an incident leveraging the IRT skills. This model is useful in limited circumstances where the local site team has appropriate skills to respond to an incident. This model may also be viable when the application or system is very specialized. In this case, the local team is better equipped to deal with the incident.

When the central IRT is in a coordination role, it becomes a facilitator among parties involved in the incident response. This model is useful when the response covers multiple geographical regions. In that case you might have to coordinate with IRTs in each location. In this model, the central IRT functions as the lead to facilitate the immediate response. The central IRT also coordinates the root cause analysis.

Once you determine the type of IRT model you’ll use, you need to construct the actual charter. This includes setting specific goals. The goals must be simple and realistic. Overly ambitious goals create both a credibility and execution problem. It’s important during an incident that the team focuses on specific achievable goals. These goals can include response times to incidents and level of cost containment. These goals will be used to create policies and processes and influence the selection of tools. For example, if the charter requires an on-site response in 30 minutes or less, the goal will drive a certain staffing level.

The structure of the charter document itself is simple and concise. A typical charter includes the following sections:

• Executive summary—Provides background on incident response and the importance it has to the organization. This section defines why the IRT exists and the type of incidents it handles.

• Mission statement—Defines the overall goals of the IRT. It also describes what the IRT is responsible for achieving. The mission statement is used to gauge the effectiveness of the IRT.

• Incident declaration—Defines an incident. It also describes how an incident is declared. This section becomes the basis for creating a process to activate the IRT team.

• Organizational structure—Documents how the IRT is aligned within the organization. It also indicates how the members are managed during an incident.

• Role and responsibilities—Describes the purpose and types of activities for each IRT member. This is important in the selection of the right team members. It’s essential to remember that you need to fill these roles with capable individuals.

• Information flow—Defines how information will be disseminated. It establishes the central team responsible for collecting, analyzing, and communicating incident information to the upper levels of management. This insures the IRT is accountable for being the central point of contact.

• Methods—Defines the manner in which the goals will be achieved. This may include a list of services the IRT team will provide.

• Authority and reporting—Describes what authority the team has. This section defines the source of the IRT’s authority. For example, the authority can be assigned by upper management in response to specific regulatory requirements.

A charter would not contain a detailed line budget. Funding should be included in the department budget as an annual expense. This avoids having to rewrite the charter every time there are changes in the budget.

Incident Response Team Members

The IRT members typically represent a cross-functional team. These team members are from several departments and bring together multiple disciplines. Being part of this designated team allows members to coordinate their efforts. They can also train together on how to respond to an incident. The team can offer a centralized, full-time service depending on the size of the organization and volume of incidents.

The IRT is comprised of a core team supplemented with specialties, when needed. These specialties are brought in based on the type of incident. Usually, full-time IRT departments exist to support very large organizations and the government.

Most organizations activate the IRT when a major incident occurs. In this case, the management of the process comes out of the information security team. Members outside the security team have normal job responsibilities. In the event of an incident, the team is pulled together to deal with the immediate threat. Once the threat is stopped, the team’s mission shifts to incident analysis. This analysis determines the cause of the incident and formulates recommendations. Once the final report on the incident is issued the team is disbanded.

The IRT usually includes members of the information security team along with representatives from other functional areas. Common IRT members include:

• Information technology subject matter experts (SMEs)—The information technology subject matter experts have intimate knowledge of the systems and configurations. These individuals are typically developers and system and network administrators. They have the technical skills to make critical recommendation on how to stop an attack. The SMEs chosen for each incident response effort will vary depending upon the type of incident and affected system(s).

• Information security representative—The information security representative provides risk management and analytical skills. He or she may also have specialized forensic skills needed to collect and analyze evidence.

• Human resources (HR) representative—The human resources representative provides skills on how to deal with employees. Breaches do not always come from outside attackers. When internal employees are involved, the HR representative can advise the team on proper methods of communicating and dealing with the employees. They are experts on HR policies and disciplinary proceedings or employee counseling.

• Legal representative—The legal representative has an understanding of laws and regulatory compliance. This person can be a valuable advisor in ensuring compliance. His or her work will involve reviewing the incident response plans, policies, and procedures. During an incident the legal representative can help facilitate communication with law enforcement. This person can examine the ramifications of decisions. The representative can also provide expert guidance on legal issues, such as the notification of employees or customers affected by a breach.

Legal representatives can also advise IRT members how to conduct themselves to preserve attorney-client privilege. When investigations are conducted by a legal representative as part of his or her duties to an organization, the communication is considered confidential and not subject to certain disclosure.

• Public relations (PR) representative—The public relations representative can advise on how to communicate with the public and customers who might be impacted by the incident. This is valuable to ensure that accurate information gets out and damaging misconceptions are prevented.

• Business continuity representative—The business continuity representative understands the organization’s capability to restore the system, application, network, or data. This individual also has access to call lists needed to contact anyone in the organization during off hours.

• Data owner—The data owner understands the data and the business. As data owner, he or she understands how the data should be handled. The data owner understands the control environment. Because data owners are business leaders they also understand the data’s impact to the business.

• Management—Management plays a key decision-making role. Management approves the response policy, charter, budget, and staffing. Management also makes the decision to turn to law enforcement and outside agencies. Ultimately, management is held accountable for the outcome of the incident response effort.

“Emergency services” is a broad category related to any outside agency. These agencies might include police, fire, and state and federal law enforcement. They bring government authority. They can also be useful in tracking down the identity of the hacker. It is rare that emergency services are part of the IRT core team. However, it does occur when the sensitivity of the breach requires specialized support. This can happen when there is a breach of a government or financial services firm that requires law enforcement support. More often, emergency services are simply coordinated through the IRT. As can be seen from this list, the IRT team has a vast array of skills available. You can add additional members as needed to deal with an incident. The team’s effectiveness will be determined by how quickly a coordinated and focused effort can be deployed.

Responsibilities During an Incident

The IRT is the single point of contact during an incident. It provides management with information as to what has occurred and what actions are being taken. It serves as the repository for all related incident information. Keeping a repository to determine the root cause of the incident is an important team function.

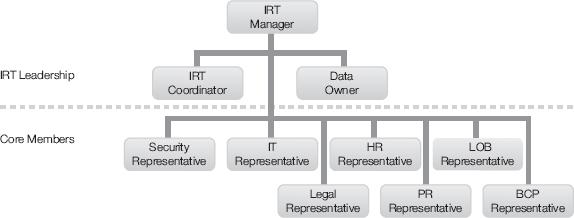

During an incident a core team is formed to respond to the threat. Figure 12-1 depicts a typical IRT core team. Not all members of the core team will be activated for every security event. Some security events are small and localized and thus need a smaller core team. Other events are major and impact the entire enterprise, requiring maximum effort by all core team members. At the time of a security event, the IRT manager makes a determination as to the resources needed to address the specific incident. Additionally, notice that upper management is not considered part of the core team. Instead, upper management is a consumer of the results of the core IRT. Upper management is, however, a critical decision-maker in responding to an incident.

Users on the Front Line

It’s the responsibility of all users in an organization to support the efforts of the IRT. When the IRT responds to an incident, time is of the essence. It’s important that the users on the front line provide quick response to requests for information. Such requests may include preserving evidence. The users may be requested to document events and assist in gathering evidence.

The users on the front line also play an important role in detecting an incident. You increase the likelihood that incidents are detected early when an alert user reports suspicious activity.

System Administrators

The system administrator may be a core member of the IRT team. System administrators help analyze the threat and recommend immediate response. These individuals know the technology and technical infrastructure. They know how it’s been customized. They are in a good position to assist with the response.

System administrators have the authority to make critical changes to repel an attack. The term system administrator can mean system, application, and network administrator. These individuals have the skills to identity anomalies to configuration and ability to respond. For example, they can disconnect devices from the network.

System administrators would also be critical to recovery of the environment. Administrators typically perform reconstruction. This is an important task that often needs to be performed to resume operations.

Information Security Personnel

The information security team has several roles during an incident. Team members may be the first to recognize the security breach. This is because the security team monitors the environment for signs of security breaches, such as intrusion detection alerts. In addition, information security staff members understand the layers of security. They understand the points of potential breach.

The incident response process is typically designed and managed by information security personnel. Security personal are either directly or indirectly involved in most IRT activities. These activities include:

• Discovery

• IRT activation

• Containment

• Analysis and threat response

• Incident classification

• Forensics

• Clean-up and recovery

• Post-event activities

The information security team often provides management and oversight of an incident response. They are facilitators and subject matter experts on security and risk. As such, they may or may not be the individuals tasked with performing the activities listed above. In some organizations, these functions are performed by information security personnel. The security team is often responsible only for ensuring the activity occurs. For example, forensic investigations demand a highly specialized skill set. They require significant training and special tools. Forensic investigations can include the basic review of a desktop for inappropriate content. They can also involve a much deeper review of databases, firewalls, and network devices. Many organizations do not have the skills and tools to do a forensic review. Some organizations have only basic capabilities. Information security personnel often arrange for a forensic review through an outside firm.

Security personnel also ensure reviews are conducted after an incident to ensure lessons are learned and adopted. The role information security personnel most often perform is writing the final incident report to management. This role makes sense because in their oversight role they see all the issues. They track the timeline of the event. They can see the big picture and combine all the incident issues into a single document.

Management

Management provides authority and support for the IRT’s efforts. When parts of the organization are not supporting or reacting quickly enough, it is management’s responsibility to remove barriers.

Management also makes key decisions on how to resolve the incident. It’s important to remember that the IRT recommends and management approves. If a purely technical decision needs to be made, the IRT operates independently. But a decision that significantly affects the business should be escalated to management, if possible. Management should empower the IRT with sufficient authority to take drastic action quickly when time is critical.

One of the early decisions during an active incident is whether to “pursue” or “protect.” In other words, does the organization want to allow the breach to continue for a period of time? This might be done so the attacker’s identity can be traced and evidence of activity gathered. Such evidence would be important to successful prosecution of the attacker. Alternatively, the organization can choose to immediately stop the attack. This approach to “protect” the network means the business could recover more quickly, but the attacker might not be caught and might try again.

The determination to “pursue” or “protect” is a business decision that management must make. This decision affects the response to the attack. Management must make other decisions during an incident, such as approving additional resources.

Support Services

This is a broad category that refers to any team that supports the organization’s IT and business processes. The help desk, for example, would be a support services team.

During an incident the help desk may be in direct contact with customers who are being impacted by the attack. The help desk, at that point, becomes a channel of information on the incident. It’s vital that the help desk provide a script of key talking points during an incident. Such a script can be very short and only refer questions to another area. Or the script can give more detail with the intent of keeping the public informed. These scripts should be developed and distributed by the PR department.

Other Key Roles

The IRT manager is the team lead. This individual makes all the final calls on how to respond to an incident. He or she is the interface with upper management. The IRT manager makes clear what decisions management needs to make. This person also advises management of the ramifications of not making a decision.

The IRT coordinator role is to keep track of all the activity during an incident. This person acts as the official scribe of the team. All activity flows through the IRT coordinator, who maintains the official records of the team. It’s a critical position because what is recorded becomes the basis for the reconstruction of the event to determine a long-term response.

Business Impact Analysis (BIA) Policies

A business impact analysis (BIA) is the first step in building a security response and business continuity plan (BCP). Not all security events will require a recovery plan. However, in the event that a security incident creates outages, you need to know which processes are most important to the business and provide for their recovery first. You can use the BIA to coordinate the security and business responses to minimize losses.

Many BIAs are based on building out multiple scenarios. Each scenario assumes a worst-case situation, such as that the entire infrastructure has been destroyed or disabled. These scenarios can range from hurricanes to security breaches that create an outage. Security breach scenarios should be part of the BIA process.

The main intent of a BIA is to identify which assets are required for the business to recover and continue doing business. This identification of key assets and business priorities can then be used to by the IRT manager to drive key decision making during an incident. These assets include critical resources, systems, facilities, personnel, and records. Additionally, the BIA identifies recovery times.

![]() TIP

TIP

Keep in mind that the BIA process is used to recover from a variety of incidents, not just security breaches. As a result you need to pick and choose the information most relevant for the IRT’s needs.

Once the data is collected, you need to perform an analysis. Compile all requirements and integrate the knowledge into the incident response processes.

Component Priority

Use the BIA to identify adverse effects on the organization. During this process you identify key components. A component can be a function or process. How detailed the component definition is depends on the organization. It must be of sufficient detail that the impact on the business is clear and a recovery strategy can be selected.

The source for this information is the business itself. A BIA cannot be conducted in isolation. It is the business that must establish the priority of components. This phase of the BIA has the following objectives:

• Identify all business functions and processes within the business.

• Define each BIA component.

• Determine the financial and service impact if the component were not available.

• Establish recovery time frames for each component.

One of the most important parts of the BIA is the determination of dependencies—which components depend or rely on other components. This includes dependency on other BIA components. The BIA must also identify specific resources, such as technology and facilities. Other dependencies may include specific skills in short supply. The key objectives of this phase of the BIA are to:

• Identify dependencies, such as other BIA components

• Identify resources required to recover each component

• Identify human assets needed to recover these components

Impact Report

Once you complete the assessment, you compile the results, formulating recommendations and integration points into the IRT process.

With this in hand, the business can make decisions. The BIA impact report is not just issued unilaterally by one office or group. You should develop it as a collaborative effort among key stakeholders. These stakeholders include executive leadership, risk teams, IT, and the business. The process of producing the report creates the consensus. Most important, the collaboration process builds the political will to implement the BIA recommendations.

The key objectives of this phase of the BIA are to:

• Validate findings of the BIA report

• Create consensus for its findings and recommendations

• Provide a foundation for other assessments

• Start educating individuals who are key to recovery

The BIA final report is an essential component of an organization’s business continuity. It becomes the key document in planning the IRT process. It sets the organization’s priorities for IRT responses and for funding IT resiliency efforts. Resiliency is a term used in IT to indicate how quickly the IT infrastructure can recover from an outage.

Development and Need for Policies Based on the BIA

The BIA describes the mission-critical functions and processes. This report leads to further assessments that identify threats and vulnerabilities. You typically produce a BIA annually. Next, you compare the findings to existing security policies. This comparison identifies gaps that may be opportunities to improve policies.

As a business changes over time, the BIA is an excellent way to understand the business. This top-priority list of business processes helps focus security efforts to protect the most vital assets of the business. It also and drives security decisions on how these assets are to be protected and recovered.

Procedures for Incident Response

There are a number of key steps necessary to effectively handle an incident. These steps are outlined in the incident response procedures.

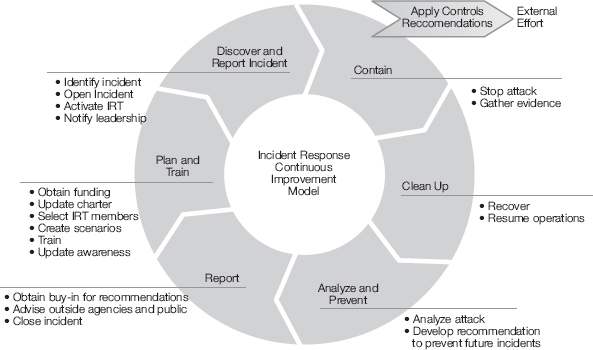

Figure 12-2 depicts the basic steps of an incident response procedure. Notice the model is built as a continuous improvement model. This means that as lessons are learned from incidents they are used to improve the incident response program itself. Notice that the controls in place before the incident are improved by people outside the IRT. Implementation of control recommendations is typically not handled by the IRT members. Each of the steps in Figure 12-2 is discussed in this section of the chapter. The important takeaway is that incident response is not a one-time process. It takes significant time and effort to create and support an IRT. The organization’s commitment and appropriate delegation of authority is essential to responding to incidents quickly and effectively.

Discovering an Incident

Discovering an incident quickly is a complex undertaking. It requires a solid understanding of normal operations. It also requires continuous monitoring for anomalies. It requires that alert employees report unusual events that can be indicators of an incident. An enterprise awareness effort must teach employees how to report suspicious activity.

FIGURE 12-2

Incident response continuous improvement model.

The signs of an incident can be obvious or subtle. The number of possible signs is enormous. The following is a small sampling:

• Suspicious activity of a coworker is noticed, and accounts within the department’s control do not balance.

• An intrusion detection sensor alerts that a buffer overflow occurred.

• The antivirus software alerts infection across multiple machines.

• Users complain of slow access.

• The system administrator sees a filename with unusual characters.

• The system administrator sees an unknown local account on a server.

• The logs on a server are found to have been deleted.

• Logs indicate multiple failed logon attempts.

These signs do not necessarily mean that an incident has occurred. However, each needs to be investigated to make sure there has been no breach. Some incidents are easy to detect. On the other hand, small, unexplained signs may only hint that an incident has occurred. Such a small sign might be a configuration file that has been changed. A well-trained and capable staff is necessary to evaluate the signs of an incident.

Reporting an Incident

It’s important to establish clear procedures for reporting incidents. This includes methods of collecting, analyzing, and reporting data. When you receive a report of an incident, classify it. This process is often called “triage.” Triage is an essential part of the incident response process. The triage process creates an immediate snapshot of the current situation. This is used to assess the severity of the threat. When the incident reaches a certain severity, the IRT is activated. This is the official declaration of an incident.

It’s important to note that many security incidents are isolated occurrences, such as computer viruses. These are easily handled with well-established procedures. When an incident is reported, the triage process must be staffed with well-trained individuals who can classify the incident and its severity. A sample severity classification is as follows:

• Severity 4—A small number of system probes or scans detected. Or an isolated instance of a virus. Event handled by automated controls. No unauthorized activity detected.

• Severity 3—Significant numbers of system probes or scans detected. Or widespread virus activity detected. Event requires manual intervention. No unauthorized activity detected.

• Severity 2—Limited disruptions to business as usual (BAU) operations are detected. Automated controls failed to prevent the event. No unauthorized activity detected.

• Severity 1—A successful penetration or DoS attack detected with significant disruption of operations. Or unauthorized activity detected.

There’s no one standard approach to assessing the severity of a reported incident. You may choose to allow the existing procedures to handle severity 3 and 4. The IRT may be activated to handle severity 1 and 2. You want to have a clear definition of terms. Severity 1 uses the term “significant interruption of operations.” That definition might vary among organizations. You do not want to interpret definitions so strictly that the definitions lose common sense. For example, consider a breach of the scheduling system for lawn care at a major organization. Yes, it’s a successful penetration. However, it is doubtful it would trigger a severity 1. Although it may seem like a silly example, that’s the problem you have with acting on pure definitions. Definitions cannot cover every situation. The best practice is to use professional judgment in assigning severity classifications. Definitions should provide guidance but not prescriptive rules.

A severity classification alone is not used in determining a response. You should also consider the incident classification to understand the nature of the attack. For example, there is a substantial difference between a server being down due to a denial of service and an unauthorized access to your credit database containing millions of customer records.

A senior leader in the information security team is typically called to make the formal declaration decision. This person is the chief information security officer or a delegate. His or her responsibility is to ensure the analysis is sound and appropriate to declare an event. Once an incident is formally declared, the IRT response timeline starts. Triage captures all the actions taken to that point. The process activates the IRT plan and also notifies upper management. The documentation includes what the basis for the severity was.

Containing and Minimizing the Damage

There are several quick actions you can take to contain the incident. This might include blocking the Internet Protocol (IP) from which the attack is being launched. It also might include disabling the affected user ID or removing the affected server from the network.

Before a response can be formulated, a decision needs to be made. This involves balancing the needs of the business and the need to pursue the attacker. The BIA can help facilitate that decision. Depending on the impact documented in the BIA and the assets at risk, you can make a decision to allow the breach to continue to gather information on the hacker, or stop the breach immediately. In simple terms, if low-value assets are being attacked, then you could choose to allow the breach to continue in order to gather information on the attacker. If high-value assets are being attacked, you must stop the breach immediately.

FYI

An organization can use different terms to represent the IRT process and core team. The terms may be different, but the core objectives are the same: Services are to be protected and restored when needed, financial losses are to be minimized, and lessons are to be learned.

You will obviously not know the type of incident in advance. Therefore, you may find that getting preapproval from management to take action is difficult to impossible. A decision on what action to take should come from upper management. However, management needs to understand the damage that will occur by allowing the attacker to continue. Having a protocol with management can establish priorities and expedite a decision. The BIA scenario discussion can help expedite leadership understanding of the organization’s priorities and choices organization. Business leaders should understand in advance the type of decisions they will be asked to make and the range of implications involved.

Allowing an attacker to continue provides you an opportunity to gather evidence on the attack. It also provides an opportunity to work with law enforcement to determine the attacker’s identity. However, many organizations are not equipped to perform such analysis. Also, the legal department will need to be consulted, because allowing a breach could have legal consequences. The most common response is to stop the attack as quickly as possible.

The IRT will work to classify the attack. It will also work to determine the best means to stop it. You should document each step of the decision-making process.

It’s important to have a set of responses prepared in advance. The initial analysis provides the picture of the threat to prioritize a sequence of pre-rehearsed steps. This could range from taking the server offline to blocking outside IP addresses. These predetermined responses should be well documented. Documentation should include what level of authority is needed to execute. For example, management may grant the IRT permission to block overseas IP addresses. Blocking domestic IP addresses, however, may need management approval. In that case, management should be alerted early when domestic IP addresses are involved. Such an alert would advise management of the situation and ensure someone is available to make a quick decision.

An important part of containment is evidence-gathering. Parts of the IRT team will be focused on stopping the attack while others take snapshots of logs, configuration, and other evidence. Remember, a successful breach is a crime scene. If there’s a chance you can prosecute the attacker, it’s important to gather as much evidence as possible. You should also disturb the environment as little as possible. This is very difficult when you’re trying to stop an attack. However, it’s important to be aware of the need to collect evidence.

Cleaning Up After the Incident

A core mission of the IRT is to ensure efficient recovery of the operations. Recovery includes ensuring that the vulnerabilities that permitted the incident have been mitigated.

The recovery phase begins once the threat has been contained. You can implement an effective recovery strategy together with the business continuity plan (BCP) representative. This may require restoring servers and rebuilding operating systems from scratch. The next step would then be to test the affected machines and data. The testing should include looking for any signs of the original incident, such as virus or malware. Once you test the servers and systems, you can certify them to be put back into production.

During the containment phase, you have little time to gather evidence. You have more time in the clean-up phase. However, management may pressure you to resume operations. Image the damaged computer(s), if possible, for further analysis after operations have resumed. That way you know the exact state prior to recovery. There are forensic tools that can perform this function quickly and effectively.

If your organization is successfully attacked, it may be attacked again. It’s important that the security controls are hardened to withstand another attack. It is often a good idea to install additional monitoring after systems are brought back online. You can use the additional monitoring to validate that the systems have been hardened. You can also use additional monitoring to change how management approaches future attempts to breach the same systems.

Documenting the Incident and Actions

As a focal point for the enterprise, the IRT can gather information across the organization. The IRT assesses the information gathered during and after the incident to gain insights into the threat. It’s important that all status reports be issued through the IRT manager. Status reports are internal communications between the IRT and management. However, you should assume that others may end up viewing them. They might even end up in a court of law. You should avoid speculation in these reports. The reports should stay with the basic facts. These include what you know and what you are doing about it.

You should start incident analysis immediately upon declaring an incident. Quickly determine the type of threat. Then determine the scope of the incident and the extent of damage. This will allow you to determine the best response. During this analysis you are collecting information to contain the incident. You are also collecting it for the future forensic analysis.

Collecting forensic evidence is an important part of the IRT’s responsibility. This means collecting and preserving information that can be used to reconstruct events. Analysis depends on gathering as much information as possible about the following:

• What led up to the event

• What happened during the event

• How effective the response was

There are specific tools and techniques used to collect forensic evidence. It’s important that a trained specialist collects the information. This is because the evidence may end up being used in a court of law. The gathering of information must follow strict rules that the court finds acceptable.

Part of these rules involves a chain of custody. It’s not only important that the information be gathered a certain way. It’s also important that the information be stored securely after it’s collected. Chain of custody is a legal term referring to how evidence is documented and protected. Evidence must be documented and protected from the time it’s obtained to the time it’s presented at court.

There is a basic approach to proving that digital evidence has not been tampered with. It is to take a bit image of machines and calculate a hash value. The hash value is obtained by running a special algorithm. This algorithm generates a mathematical value based on the exact content of the bit image of the machine. The hash value is essentially a fingerprint of the image. When the image is submitted to the court, another hash value is taken. When the two digital fingerprints match, it proves the image was not tampered with. If one bit of data on the bit image copy is altered in any way, the hash value would change.

The IRT coordinator should maintain an evidence log. All evidence associated with the investigation should be logged in and locked up. If any evidence needs to be examined, it’s logged out and then logged back in. Where possible, once evidence is logged in, only copies should be logged out for further review. It is important to maintain a chain of custody to be sure the material is not altered or tampered with.

Analyzing the Incident and Response

The goal of the analysis is straightforward. It is to identify the weakness in your control. Knowing the weakness allows you to continuously improve your security. It helps prevent the incident from occurring again. As you examine your control, you may find other weaknesses unrelated to the incident. Ideally, you want to be able to identify the following:

• The attacker

• The tool used to attack

• The vulnerability that was exploited

• The result of the attack

• The control recommendation that would prevent such an attack from occurring again

Each incident is different and may require a different set of techniques to arrive at these answers. There are some steps you can take to help the analysis:

• Update your network diagram and inventory—Be sure to have a current network diagram and inventory of devices available

• Profile your network—Map the network traffic by time of day and keep trending information

• Understand business processes—Understand normal behavior within the network and business

• Keep all clocks synchronized—Be sure the logs all have a synchronized timestamp

• Correlate central logs—Be sure logs are centrally captured and easily accessible

• Create a knowledge base of threats—Create and maintain a library of threat scenarios

Understanding the environment makes it easier to detect suspicious activity. As you become more familiar with the business processes, you can consider new threat scenarios. These new threat scenarios need then to be fed back into the BIA process. Over time, this builds institutional knowledge on what risks the business faces and how to properly respond.

The key point is to use these incident analyses to be proactive in defending against threats. The reports examine how to close a security weakness. The reports also examine why the security weaknesses were not originally considered and closed. Reports improve the risk assessment process as much as they help close a specific vulnerability.

Creating Mitigation to Prevent Future Incidents

Part of the analysis is to trace the origin of the attack. This is important for preventing future incidents. This activity involves finding out how hackers entered the application, systems, or network. The analysis should create a storyboard and timeline of events. The storyboard is a complete picture of the incident. This includes actions taken by the hacker, employees, and IRT team.

The IRT may engage outside help in determining the hacker’s identity. This outside help may include consulting firms that specialize in forensic investigations. It may also include various law enforcement agencies. These outside resources have established contacts with Internet service providers (ISPs). They have the ability to track down online users. Although the exact identity of the hacker may not always be determined, these firms can often identify the point of origin. In other words, you may never know the hacker’s real name. However, there’s a good chance you will know the country and city of origin. These firms can also provide a profile of the attacker. Such a profile might include the attacker’s level of skill and potential motive. The attacker might be a high school student. It might also be a foreign government. This information could be valuable to know in determining a response.

It is vital that an organization learn from incidents to improve its controls. Sometimes that may mean changing its policies and procedures. Other times it may mean improving security awareness to reduce human error. It can also mean making changes in your security configuration standards.

A final IRT incident report should be published for executive management. This report will bring everyone up to date on the risk that was exploited. It will also show how it was mitigated. The report should answer the following:

• How the incident was started

• Which vulnerabilities were exploited

• How the incident was detected

• How effective the response was

• What long-term solutions are recommended

After a major incident, you should hold a lessons-learned meeting with key stakeholders. This meeting will review key points in the IRT incident report. A lessons-learned meeting should also be held periodically for minor incidents. You can use an annual trending report as an effective measure of progress in reducing risk.

The lessons learned should include how to improve the incident response process. These lessons can be used to help training. They can also help improve IRT skills. Skills can be improved using methods such as additional training. They can also be improved through testing using new scenarios built from the lessons learned.

Handling the Media and Deciding What to Disclose

The PR department will play an important role in communicating the incident to the media and impacted parties. The PR department can correct misinformation that could damage the company’s reputation. The decision to release information to the public is often handled through a press release.

The PR department is also a point of contact for press inquires. If a reporter contacts the PR department, it’s important that the PR department have the latest information on the incident. How much information to release is a decision for management. It is the role of the IRT management to make sure the PR representative has the core facts. It’s then up to management and the PR department to work out the type of disclosure that’s appropriate for the situation.

Notification may be required that will impact consumers. Many privacy laws require consumers to be notified if their personal information has been breached. Once again, the PR department will work with management and legal to determine what needs to be disclosed to stay in compliance.

Business Continuity Planning Policies

A business continuity plan (BCP) policy creates a road map for continuing business operations after a major outage or disruption of services. BCP policies establish the requirement to create and maintain the plan. The BCP policies give guidance for building a plan. These include elements such as key assumptions, accountability, and frequency of testing. BCP policies must clearly define responsibilities for creating and maintaining a BCP plan. The BCP plan identifies responsibilities for its execution.

The plan must cover the business’s support structure. The support structure includes things like facilities, personnel, equipment, software, data files, vital records, and relationships with contractors and service providers. When you must have minimum downtimes, BCP planning and documentation must have a high degree of precision.

There’s no room in BCP planning for individuals to start asking, “What does this mean?” A risk assessment from the BIA will help. It can identify control weaknesses that need to be considered in a BCP. The BCP policies and procedures include a review of existing risk assessments. This review determines control weaknesses that could affect recovery of the business. For example, assume a key component of your BCP depends heavily on a strategic vendor relationship. This could include executing your mission-critical application from the vendor’s facilities for a time.

But suppose a recent risk assessment has identified serious control weaknesses based on poor physical security at the vendor’s facilities. Well-defined BCP policies would require a gap analysis along with the risk assessment. This approach allows you to assess the vendor weaknesses as part of the BCP process. These weaknesses can become scenarios discussed in the BIA. In this example, you may choose to continue this strategic relationship but consider how to mitigate the vendor’s physical security risk.

As previously mentioned, the BIA is the initial step in the business continuity planning process. The purpose of a BIA is to identify the company’s critical processes and assess the impact of a disruptive event. The desired results of the BIA include:

• A list of critical processes and dependencies

• A work flow of processes that include human requirements for recovering key assets

• An analysis of legal and regulatory requirements

• A list of critical vendors and support agreements

• An estimate of the maximum allowable downtime

The BIA is the foundation on which a BCP is developed. The individuals accountable for the BCP should be key stakeholders in the BIA process. These include the auditors who must assess the adequacy of the planning process. Poor-quality results in the BIA will lead to poor-quality BCP planning.

Dealing with Loss of Systems, Applications, or Data Availability

The list of critical systems, applications, and user access requirements comes from the BIA. The BIA also includes maximum downtime. This drives the selection of recovery methods and techniques. As the recovery window is shortened, there must be more reliance on technology. People can react only so fast. Speed of reaction can be a problem if a disaster strikes while individuals are most distracted, such as during a long holiday weekend. Key staff may be away for the holidays and out of communication. In that case, you should rely more heavily on automation and well-documented plans that others can execute in the absence of that staff.

In the case of a long holiday weekend, it may take hours to connect with key personnel who have a reasonable understanding of the event. At worst, it may take days. Coping with the loss of systems and technology requires effective planning. It also requires coordination, often with a greater reliance on manual processes. These manual processes must be well defined.

The BCP policies require the same level of care for the information. Assume a clinic faces a disaster. It chooses to capture information by hand. The information captured needs the same level of care as if the information were entered into a computer. The information may be covered by HIPAA and thus require the same diligence in security and handling. The BCP is not just about recovery; it must detail the access controls needed to protect the information during recovery. These controls might include securely storing and transporting the information.

Response and Recovery Time Objectives Policies Based on the BIA

The recovery time objective (RTO) is length of time within which a business process should be recovered after an outage or downtime.

It’s important to understand that the RTO relates to the business process. It does not relate to the dependent components, such as the technology. The RTO is the measurement of how quickly individual business processes can be recovered. The RTO is a natural extension of the BIA. It identifies the maximum allowed downtime for a business process. The maximum allowed downtime is based on the business tolerance for loss. This in turn becomes the RTO. That is why the business continuity planner is part of the BIA process.

The continuity planner understands the capabilities of the organization to recover from a disaster. The planner should be able to catch an unrealistic RTO set by the business during the BIA process. For example, the business may state that it requires near real-time recovery of its applications in the event of a disaster. Few organizations could achieve that goal. The BCP planner facilitates a candid discussion on the cost of recovery and organization’s capabilities. The continuity planner can also push requirements that increase costs.

RTO policies often include a discussion of recovery point objectives (RPOs). The RPO is the maximum acceptable level of data loss from the point of the disaster. The RTO and RPO may not be the same value. Assume that an organization has a maximum RTO of two days. The same organization can also have a RPO of one week. This is to say, the business can afford to lose a week’s worth of data. This is information the IRT manager needs to know in making a decision on how to handle a major breach response. This can be acceptable if the business can take the restored data from a week earlier and reconstruct the lost data from there. An example is financial data based on calculations that can be rerun.

The RPO can be shorter than the RTO. In that case, the business is saying the business process can be down longer. However, when business operations resume, the business needs the data from an earlier point, such as the point of outage. It’s important to understand that the RPO relates to the data, not to a single RTO.

When you look at the RTO and RPO, the requirements to recover a business successfully emerge. These requirements drive the selection of recovery technology and design of the BCP.

Best Practices for Incident Response Policies

Incident response policies recognize that an organization needs to build strong external relationships. The policies need to identify which role is responsible for maintaining these relationships. For example, the legal department often maintains relationships with outside law firms.

The IRT may wish to establish a formal contract with consulting firms that specialize in incident response. These firms can provide a depth of knowledge on specific attacks. Such knowledge may not be available within the organization. Because consulting firms respond to multiple incidents across many customers, they are able to respond to incidents rapidly.

Incident response policies and capabilities need to be tested. Testing can also act as training for the IRT. Training ensures the staff has the required skill set to respond quickly to an incident. Ideally, the test should not be announced, so the activation process can also be tested.

The effectiveness of the IRT and its related policies needs to be measured. This is to ensure that the IRT is achieving its stated goals. The measurement should be published annually with a comparison to prior years. The measurements should include the goals in the IRT charter, plus additional analytics to indicate the reduction of risk to the organization. This might include:

• Number of incidents

• Number of repeat incidents

• Time to contain per incident

• Financial impact to the organization

Disaster Recovery Plan Policies

The disaster recovery plan (DRP) consists of the policies and documentation needed for an organization to recover its IT assets after a major outage. The business impact analysis drives the requirements for the business continuity plan. The BCP drives the requirements for the disaster recovery plan. These include software, data, and hardware. The DRP policies and resulting plan address all aspects of recovering an IT environment.

Disaster recovery planning considers people, processes, and technology. In many cases, laws and regulations outline the requirements for a DRP. In developing a DRP, it’s important to work with your organization’s legal department to ensure requirements are being met. For example, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires organizations with 10 employees or more to have a DRP. The law is meant in part to protect employees’ health and safety during a disaster.

Disaster Declaration Policy

The disaster declaration policy outlines the process by which a BCP and/or DRP is activated. It’s not unusual to have an IT disruption event that is localized in the technology infrastructure.

If an event causes major business outages, the BCP would be activated. Localized technology outages often impact the business. They may not rise to the level of a disaster. Still, in those cases, the DRP portion of the BCP plan would be activated. A server may go down, or a critical file be deleted. This can disable a vital application in a smaller organization. In a large organization, however, many of these events occur each month. They are considered routine and would not trigger a DRP.

The disaster declaration policy defines the roles and responsibilities for assessing and declaring a disaster. Once a DRP is activated, a number of processes and capabilities are launched. You can handle many of these activities, such as notification to staff, through automated systems. The activation of a DRP for a large, complex organization costs thousands of dollars. In this case, the decision about who can declare a disaster is tightly controlled. Once the plans are activated, you want the process to be as automatic as possible. It should be second nature for those involved.

Once a disaster is declared, it’s very hard to stop its early ramp-up stages. These might include notifying key leaders and staging recovery capability. The process for declaring the disaster is contained in the disaster declaration policy. The following is a sampling of activations the plan might also include:

• Emergency notification of personnel, stakeholders, and strategic vendors

• Alternative site activation

• Activation of the emergency control center

• Transport and housing arrangements

• Release of prepositioned assets

Many of these activities will overlap with BCP activities. The difference is that they focus on the recovery of the IT infrastructure, as opposed to business operations.

Assessment of the Disaster’s Severity and of Potential Downtime

Not all disasters are alike. There’s a difference between losing your entire data center to a flood and having a DOS attack that disables a few dozen servers. But both would activate a DRP.

Assessment of the severity occurs throughout the life of a disaster. It starts with the disaster declaration and is continually updated. You forward the information to the emergency control center. Here it’s included in the decision-making process. Performing this continued assessment of the potential downtime is important. It ensures the right resources are being allocated to the problem. Many critical business decisions during a disaster rely on the assessment of the problem’s severity. A small sampling includes:

• Allocation of resources

• Notification to customers

• Assessment of financial losses and costs

Allocation of resources gets the right people to focus on the right problem. Consider a major outage of a vital vendor application. Your IT team estimates the outage at an hour or so. Then you reassess and estimate the potential downtime to be several days. The leadership in the emergency control center may be more patient in the first case. In the second case, the leadership may be on the phone with the vendor and begin flying in additional resources.

Having realistic estimates of downtime is important for customer relations. Overly optimistic recovery estimates often lead to loss of credibility. Suppose air travelers are told they face a flight delay of 20 minutes, but then their plane doesn’t leave until three hours later. This can cause a big public relations problem when it occurs repeatedly. The best professional judgment on potential downtime is expected in a DRP. Unrealistic estimates can overcomplicate and undermine the recovery process. It’s important to keep a complete history and basis for the estimates throughout the recovery process. You can use this information in post-disaster assessments to improve your process.

Assessments during a disaster are needed to determine financial losses and costs. An extended outage will require the infusion of capital to sustain an organization throughout the disaster. The amount of capital required will depend on the duration of the outage. Borrowing money can be expensive. Accurately estimating potential downtime is important to controlling those costs. It’s important to remember this is not just about a security breach or event. Equally, you need to look at a security event as a business disruption. Business relies on an end-to-end process working. From a technology perspective this means that the system, application, and data must all be in place and working. If any one of these components is not recovered or is out of alignment, the process fails. Disaster recovery policies define what to back up, and how often, and how to recover data in case of a disaster. The DRP must align well with the BCP and the BIA.

There are unique requirements for backup and recovery for systems, applications, and data. Systems and applications are easier to recover in some ways. They change less frequently and often rely on software from vendors. Having multiple sources to recover systems and applications makes recovery easier.

The customization of systems and applications is a different story. These customization settings are commonly referred to as configuration. They must also be captured and available during a recovery. The configuration for operating systems and databases includes security controls. The DRP needs to ensure these controls are not disabled during a disaster. A subset of the DRP is a security plan that outlines how security controls will be monitored and maintained during a disaster. The plan may restrict access to key staff to improve performance and stability. Approval for access may have to go through the emergency control center. It may require CISO approval.

The key point is that security planning and execution during a disaster are important considerations when building a DRP. Recovery of mission-critical data can be more challenging than recovery of systems and applications. The value of data is often time-dependent. Data backups taken at the point of the disaster are typically more valuable than data backups from the prior month. The BIA process and data classification effort identifies the data that must be recovered.

The amount of mission-critical data depends on the organization and industry. Mission-critical data should represent a small portion of the total population, such as less than 15 percent. When the percentage is exceedingly small or large, it’s a red flag. The percentage should be challenged. The challenge may reveal weaknesses in the current controls, such as the way backups are taken. Backups should be able to isolate mission-critical data. It’s not uncommon for an error in the backup process to cause you to have to restore large volumes of data to ensure that the mission-critical data is restored. This can cause unnecessary delays.

Case Studies and Examples of Incident Response Policies

The case studies in this chapter examine various organizations that have formal incident response teams established by policies. The case studies examine how effective these teams were during a security breach.

Private Sector Case Study

An online forensic case study was published about a multibillion-dollar publicly traded company. The company is a leader in the IT infrastructure market. The company was not named in the article.

The problem: The company’s servers had been compromised to be the jumping-off point to attack a host of other companies.

The company was notified by another company of what was being attacked. The company’s administrator activated an IRT to assess the threat. The administrators were unable to find that a breach had occurred. They called in a consulting firm named Riptech, which specialized in intrusions and forensic analysis. Riptech discovered that a server had been compromised. The firm wanted to monitor the intruder’s activities. However, Riptech was advised by in-house counsel that the company was not comfortable allowing the breach to continue. Riptech managed to trace the attack to a North Dakota high school.

This case study illustrated weaknesses in the company’s incident response policies and plans. It did point to the skills and tools available to the company. In addition, information response policies were clear on the role and skill requirements to form an IRT. The team did appear to be cross-functional, as the legal department was clearly engaged. Also, the IRT was activated quickly. However, the administrators were unable to find the breach.

The incident was a good example of working with legal specialists to determine the appropriate response. Although Riptech preferred to track down the attacker, the company’s legal counsel was concerned over the potential liability of permitting a breach. The decision was to protect the organization and stop the intrusion.

The case study illustrated how forensic tools are used to gather evidence. A bitmap copy of the infected systems was made prior to the systems’ being restored. This preserved the affected server. The image could then be used as evidence or for further analysis of the incident.

The case study also illustrated the public relations approach that was taken. Because there was no breach of data, the company decided not to publicly acknowledge the attack. The article indicated the concern was public perception. The organization did not want it known that a teenager was able to breach its system.

The final incident report issued by Riptech outlined a series of control weaknesses that allowed the breach. The consulting firm helped the company restore its system and mitigate the threat in the future.

Public Sector Case Study

Northwest Florida State College reported that a data breach occurred between May and September 2012. The breach resulted in 300,000 student and past-employee records being stolen. The data breach reportedly occurred over several months in which the hacker accessed unprotected folders with key information that was then leveraged to exploit other machines.

The release information is unusual as it identified a potential root cause being “Staff not trained in understanding data classification and segregation.” The information release about the breach pointed out that the staff would mix public data and sensitive personal financial records in the same directory. This included storing public information with data containing Social Security numbers and bank routing numbers.

There were clearly multiple breakdowns of policy and security awareness. Among these breakdowns were:

• Lack of BIA planning

• Lack of security awareness

The BIA planning should have identified these student and employee records as having high value. Additionally, planning scenarios should have anticipated this type of breach. The commingling of public and private data is both a classification and process-issue defect. Had the BIA process caught this, there would have been an opportunity to correct it before the breach occurred.

While this was not caught in the BIA, this is a good example of post-incident review. In a post-incident review it’s not enough to talk about what happened. The post-incident review must also identity the root cause. Often this root cause finding is not released to the public. But knowing the root cause would allow the university to make changes to prevent it from happening again.

This is also a good example of the need for a business impact analysis. An effective BIA can be used as an effective security awareness tool. The results of the BIA and scenarios discussed allow both the security team and the business—the college, in this case—to have a common understanding of data breach risks.

Critical Infrastructure Case Study

A case study was published by the Carnegie Mellon CERT program. It described how one of the largest banks in the country started an IRT. The case study concealed the bank’s name, referring to it as AFI. The case study described the process that AFI went through to create the team and related policies.

The need for an IRT was clear to the security manager. He had observed security incidents being handled inconsistently. This was a problem because the bank was governed by certain regulations. The approach was to involve several of the risk groups and key stakeholders. The effort was jump-started by using best practices. It took several years to deploy globally. This was because of the size and complexity of the organization. The effort was initially understaffed. The effort that would be required was underestimated. Requirements were not clearly understood.

This case study is a good example of how regulated industries are required to have effective information response policies. This is also an example of an IRT that is filled with appropriately skilled individuals. There was no indication in the case study that an external firm was engaged to assist the company. It would be a best practice to engage an outside firm to help plan such an effort when internal skills are not available.

You learned in this chapter what incident response policies are needed to respond effectively to security breaches. It’s important that policies define what an incident is. They should also state clearly how to classify an event. You also learned how to build a team charter. The chapter examined the difference between on-site response teams and teams that facilitate responses. The chapter discussed key roles and responsibilities within the team during an incident. The chapter discussed how incident plans are built, including the importance of a BIA assessment. Additionally, the chapter discussed the alignment between the BIA, BCP, and DRP.