What Is an IT Policy Framework?

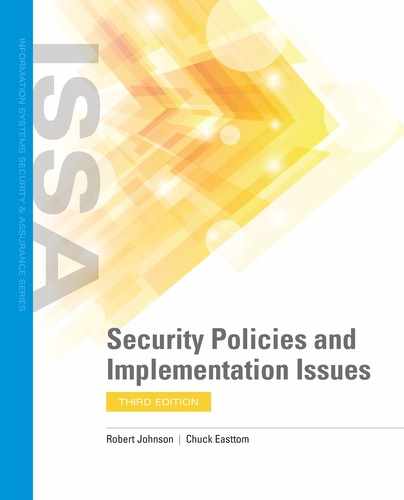

An IT policy framework includes policies, standards, baselines, procedures, guidelines, and a taxonomy. Many frameworks resemble a hierarchy or tree. At the top of the tree is a charter or program framework policy, followed by additional policies. Then there are several standards. Under standards are many guidance and procedure documents. Getting the framework right is key to a successful security program.

NOTE

NOTE

You will often hear the framework documents referred to as policies. In practice, the framework includes policies, standards, and other documents. Each type of document has a specific purpose.

FIGURE 6-1 offers one view of how you might structure an information security policy and standards library. For the framework to be useful, it must be accessible and understandable. Although most frameworks are available online, it’s not enough just to provide access. It’s equally important to ensure the documents are written at a level that is well understood and can be navigated easily. The documents must be well organized, so that users can find what they are looking for quickly.

FIGURE 6-1 A policy and standards library framework.

Building a policy framework is also like growing a tree. The roots and branches of the tree are established; then, you water the tree and allow it sufficient time to grow. Eventually it provides coverage for everyone. Over time, tree branches die off, leaves fall to the ground, new branches grow, and the tree needs pruning. A policy framework works in the same way. You give it ongoing attention to nurture the process and document content. This assures that it provides the coverage your organization needs and demands. What this means from a practical standpoint is that a policy framework does not have to be comprehensive on Day One. For example, you might have a policy that outlines the security requirements for managing encryption keys. As mobile technologies are introduced for the first time, these requirements may not provide adequate guidance or simply may not work with these new technologies. It may become clear that you need to create a separate mobile technology encryption policy.

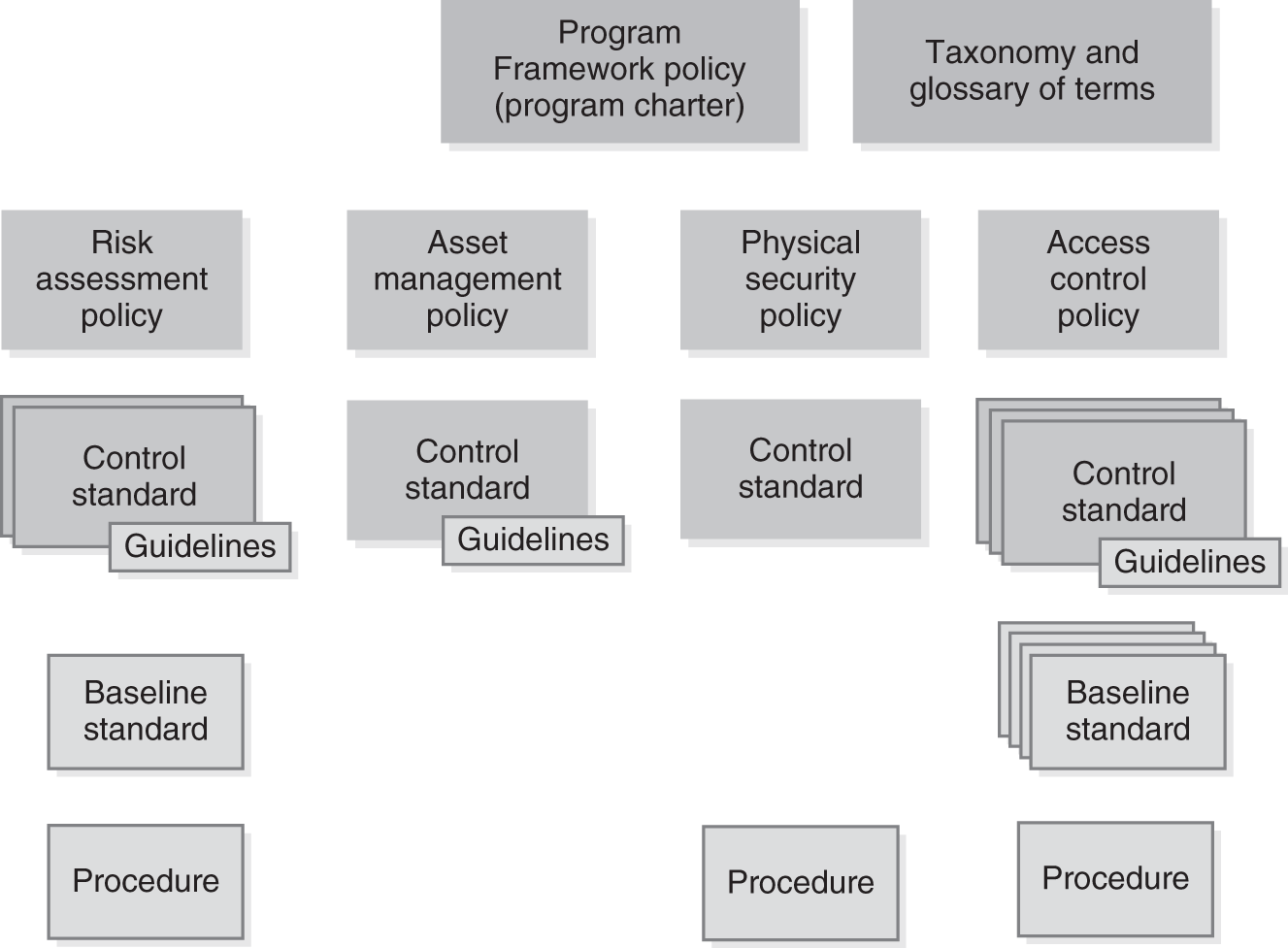

An organization’s security posture is often expressed in terms of risk appetite and risk tolerance. These two terms are sometimes misused and assumed to mean the same thing. They are not the same. Although they both are used to measure how much risk an organization is willing to accept, they have two very different purposes. Risk appetite generally refers to how much risk an organization is willing to accept to achieve its goal. This is often expressed by the impact on the organization and the likelihood of something bad happening. FIGURE 6-2 illustrates this point. Ideally you would like to face only risks in which the likelihood of the negative event is low, and even if it did happen, the impact to the organization would be minimal. But this is not an ideal world. Many security risks will have significant impact on customers and the profits of a business, so they must be understood and managed.

FIGURE 6-2 Charting risk appetite.

Typically, the security risks are managed by adding controls. Eventually a set of risks becomes simply too great for an organization to accept. These risks may relate to life and safety, or their potential impact would put the organization out of business. A security framework must have policies that clearly draw the lines to define acceptable behavior that ensures activities fall within the limits of risk appetite. As the levels of risk increase, so must the levels of control.

Risk tolerance relates how much variance in the process an organization will accept. This is often expressed in term of a percentage, such as plus or minus 10 percent. For example, assume you own a company that buys, renovates, and sells real estate. Assume your company specializes in residential real estate. As a result, there may be no risk appetite for buying a commercial office building. That is because your company, lacking expertise in the commercial sector, is at greater risk of making a mistake if it tries to make a commercial deal. The higher costs of commercial properties and fluctuations in the market could result in huge losses that put your company out of business. Consequently, commercial properties may be outside your risk appetite. Within the residential properties you do control, you set a budget for renovations. You watch every dollar spent and put in controls to ensure you come in within 10 percent of budget. You’re comfortable that as long as you manage to this risk tolerance, you can make a healthy profit.

In an information security context, it’s not always clear when and how to apply these concepts. You cannot apply risk appetite and risk tolerance to every control. You must select those controls (or group of controls) where key risk decisions must be made. For example, consider the group of controls related to security patch management. A decision must be made balancing information security and business needs over how much risk will be accepted to allow systems to run without patches to close security vulnerabilities. A risk appetite may not allow any systems with critical patches to run in production beyond five days. This would address immediate threats, and there could be a risk tolerance of 30 days (plus or minus 10 percent) established for all remaining security patches to be applied.