Target State

Target state is a general term used in technology to describe a future state in which specific goals and objectives have been achieved. It is the state you want the system to be in. In security policy terms, this future state generally describes which tools, processes, and resources (including people) are needed to achieve the goals and objectives. So, describing policy in terms of goals and objectives is important to get agreement on the target state.

NOTE

NOTE

Threat vector is a general information security term to describe a tool or path by which a hacker can gain unauthorized access. For example, accessing a website through the Internet and adding SQL injection code into an input field on a webpage would be considered a threat vector.

There are different ways to describe policy goals and objectives. The value of the policy will often be judged by how well you can describe the goals and objectives. The more persuasive the descriptions, the more people will value the policy. One of the more effective techniques is to describe goals and objectives in the following ways:

- Business risk—Describes how the policy will reduce risk to the business and, more specifically, how it will reduce risk to an acceptable level.

- Compliance—Describes how the policy will ensure the business is compliant with laws and regulations. This is particularly important with regulated industries such as health care and credit cards.

- Threat vectors—Describe how the policy will prevent, mitigate, or detect IT security threats.

Business risk can be expressed in terms of how the policy either enables the business or reduces business disruptions. This risk can also be described in business risk terms such as expressed in the risk and control self-assessment (RCSA). The RCSA is typically produced annually by the business and describes its top risks, controls, and barriers to their objectives.

For example, assume a company wants to start selling product over the Internet to overseas customers. In this case, there might be an elevated risk of fraud. Some overseas regions, such as Eastern Europe, Africa, Malaysia, Indonesia, Turkey, and Pakistan, are considered higher-risk areas. In the event of fraud, options for recovery and legal action by the merchant are limited. Taking additional security measures to prevent or detect that fraud would be seen by the business as added value. For example, a company may choose to limit sales to specific countries or regions where the perceived risk is lower, such as Western Europe or Japan. This can be accomplished, in part, by blocking certain IP addresses.

Compliance relates to the legal and regulatory mandates a business must follow. Certain security policies are required by laws and regulations. Describing how the security policies help the organization to meet legal mandates is another valuable addition to the business. It should be noted that compliance to a regulation or industry standard is a minimum level of security, not ideal. Organizations sometimes make the error of assuming that if they are in compliance with a given standard, then they are secure. Compliance should be viewed as just a baseline, minimum level of security.

Threat vectors are a business concern. A threat vector is the way in which an attack is launched. Often these are more technical threats that the business might not understand well. Describing a SQL injection attack, for example, might not have much meaning to the business executive. However, describing the results and impact to the business will be important to him or her. You can explain a SQL injection attack, for instance, as leading to the theft of customer credit card information or the takedown of the company’s website.

There should also be a policy regarding the company cybersecurity team keeping updated on current threats. This is a part of what is generally referred to as cyberthreat intelligence. Several services and websites can help a cybersecurity professional stay current with threats. A few are listed here:

- SANS Internet Storm Center: https://isc.sans.edu

- Cyware: https://cyware.com/category/cyber-threat-intelligence-news

- Threatpost: https://threatpost.com

- Cyber Threat Intelligence Feeds: http://thecyberthreat.com/cyber-threat-intelligence-feeds/

Regardless of the method used, the target state must describe in clear terms the technology, tools, and resources needed to implement the process. Additionally, to sell the need for the policy, the target state must describe the value in terms of the goals and objectives it will achieve.

TIP

TIP

Brown bag sessions are good opportunities for senior leaders to convey expectations related to information security policies. This is especially true for the chief information security officer (CISO). Such sessions provide a nonthreatening forum for the CISO to connect with various levels within the organization.

Target state describes how policy implementation is closely tied to technology controls. You can have the best policies, but if they cannot be implemented, they’re useless. The following section outlines several common technology challenges that can hinder the implementation of security policies.

Distributed Infrastructure

Security policies apply throughout the enterprise. As such, they rely on a centralized view and control of risks. You design a central set of policies and apply them across the enterprise. However, today’s technology is highly decentralized. Smart devices are mobile. Users’ laptops and desktops have tremendous computing power. Remote offices have servers and complex data closets supporting local networks. These are just a few examples. Today, many organizations also have substantial resources stored in a cloud.

All these add up to what’s known as distributed infrastructure. That’s a term for an organization’s collection of computers—including laptops, tablets, and smartphones—networked together and equipped with distributed system software so that they work together as one, even from various locations.

For many organizations, the amount of technology outside the data center is significant. How do you implement centralized security policies in a decentralized environment? It’s challenging. The target state must describe how to accomplish this. You first look at the administration of the distributed infrastructure.

Fortunately, although many technologies are distributed, many administration tools are centralized. Centralized administration tools allow for policies to be centrally distributed. A classic example is malware protection. Most organizations use a central malware management tool that keeps malware scanners up to date. The updating typically occurs when the desktop or laptop is connected to the network. An agent on the devices communicates with the central server and downloads the latest updates.

A distributed infrastructure is typically managed through an agent or an agentless central management tool. An agent is a piece of code that sits on the distributed device. As in the case of the virus scan, the agent software periodically reports back to the central management tool. An agent typically has multiple functions. The most common function is to report the state of the device back to the central server. It also receives commands and updates. In the case of the malware scan, the agent would report any malware detected and receive updates to the scanner.

An agentless central management tool has the ability and permission to reach out and connect to distributed devices. Unlike in the malware example, where the agent software pulls the updates onto the device, the agentless software is centrally housed. It pushes the changes to the device. Agentless management products use standard interfaces within the operating system or devices. They then authenticate, which grants them rights to perform their function. For example, Intelligent Platform Management Interface (IPMI) can be used as an agentless interface to Dell’s OpenManage IT Assistant tool. This tool can be used to monitor and maintain a server’s performance.

A current inventory is key to implementation in a highly distributed infrastructure. You need to know how many devices are on the network. You also need to know which devices adhere to security policies. Many organizations use discovery and inventory tools to capture and track this information. These tools track devices connecting and disconnecting from the network. They can also capture key security control information.

The combination of a good inventory count and good configuration information allows you to implement security policies in a distributed infrastructure. This is because you can assess the population of network devices and compare compliance with security policies. For example, a typical policy might state that all desktops must have updated virus protection. The inventory might indicate 2000 desktops. The central malware management tool might indicate that about 1800 desktops have updated malware protection. You can now assess the effectiveness of the security policy implementation. Approximately 90 percent of your desktops comply with the policy.

Outdated Technology

Another challenge for describing a target state is how to deal with outdated technology. Outdated technology is hardware or software that, because obsolete, makes it difficult to implement best practices consistently. Outdated technology generally does not adhere to current best practices. When that occurs, you must decide how to address the lack of security controls within policies. You have four basic choices:

- Replace the outdated technology.

- Write security policies to best practices and issue policy waivers for outdated technology that inherently cannot comply.

- Write security policies to the lowest, most common standard that the technology can support, even if it’s outdated.

- Write different sets of policies for the outdated technologies.

The ideal solution is to replace all outdated technology; however, that’s not always an option, especially in a declining economy when many organizations are cutting costs. You should, however, be aware that if you are using outdated technology, there are security threats you cannot defend against. Continuing to use outdated technology is always a last option.

Of the three remaining choices, none is good. Generally, the least objectionable choice is option 2. The technology that is not outdated will conform to policies. The technology that cannot conform is typically granted a waiver with additional hardening to mitigate risk as much as possible. Waivers provide transparency on the risks the business is accepting. At a minimum, any waiver granted should require annual renewal. This will provide an opportunity to review the waiver and the risk—and the additional cost it introduces into the control environment.

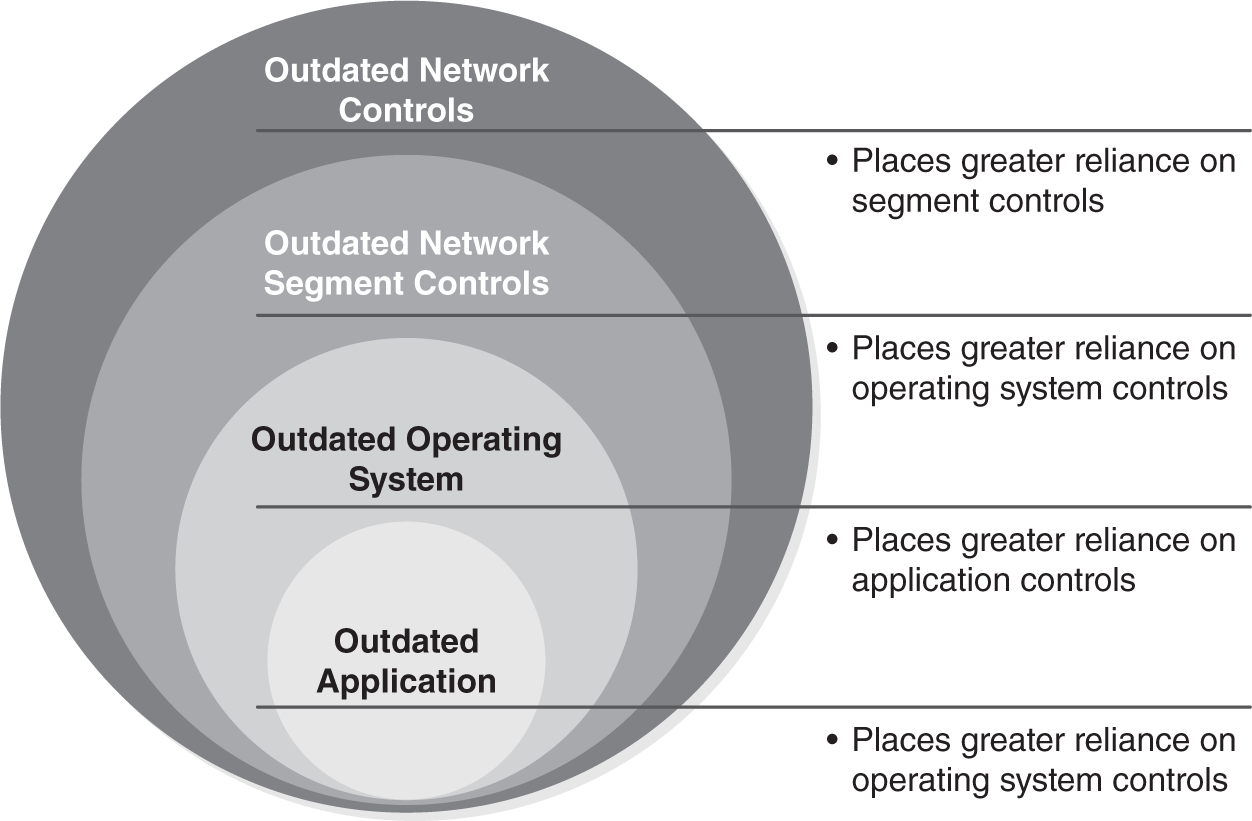

It’s sometimes less expensive to replace technology than to upgrade its security. FIGURE 13-2 illustrates that point. Assume you had outdated technology in your network. One response would be to improve segmentation controls to compensate. If you had outdated technology in the segment’s network controls, you would place more reliance on operation system controls. If your operating system technology was outdated, you would place greater reliance on application controls. Any combination of the enhanced controls might mitigate some of the risk of outdated technology. Of course, all these additional layers of controls would increase costs to the organization.

FIGURE 13-2 Expanded layers of control required for outdated technology.

Outdated technology creates security vulnerabilities. Vendors usually do not support outdated technology, so new security vulnerabilities will not be patched. Even adding additional layers of security can only go so far. There’s significant risk to having outdated operating systems. Once the operating system is breached, it’s likely the application will be breached.

Lack of Standardization Throughout the IT Infrastructure

Another technical challenge is the lack of standardization within the infrastructure. This can have several causes, but two common causes are 1) a lack of consistency with configurations; or 2) deployment of a diverse population of technologies.

The lack of a consistent configuration is a problem that arises when similar technologies are used in different ways by different lines of business. Each line of business has its own technologists applying different standards to similar technology. Assume, for instance, you have a company with physical stores and an online presence. Both lines of business have an inventory application that the public cannot access. The application may be on the same operating system and perform the same basic functions. Yet the configuration may look completely different if two different groups of administrators maintain the application.

This diversity in security approaches can be overcome in time, but it may create delays in the implementation of the security policies and increase costs. Both administration groups need to agree on a common approach to security. An implementation plan is needed so both types of configurations can migrate to the new policy in an orderly fashion.

When you have a diverse number of technologies deployed, security policies must be more generic. The policies must ensure that as much of the technology as possible can comply. That means that if one set of technologies has a weakness, the policy may choose to apply the weaker standard across the broadest set of technologies. Security policies often consider minimum standards. So, although one set of technologies has a weakness, the remaining technologies can add security beyond what’s called for in the policies. The drawback is that policies are mandatory. By removing a security requirement from policy, there’s no certainty that those additional controls will ever be applied.

Consequently, having a diverse population of technologies creates a set of tradeoffs. You want security policies to be as inclusive of the technology within the organization as possible. That may mean lowering some of the security standards at times. One option is to publish a security policy with an effective date that’s in the future. This gives the organization time to upgrade technology and configurations. Whatever approach is selected, it’s important that security policies be realistic in their expectations. Security policies should not be a theoretical exercise or an ideal state. They should reflect realistic expectations on how the organization needs to control risks.

Executive management support is critical in overcoming hindrances. A lack of support makes implementing security policies impossible. It takes a strong partnership between management and the IT security team to implement security policies. Consequently, it’s vitally important to gather support for the security program by including senior management in building the target state. Listen carefully to the executives’ needs. For example, if executives are particularly concerned about regulatory compliance, be sure the policies address compliance thoroughly. The more you can convey that the policy target state solves real problems for executives, the more likely they will be to support it.