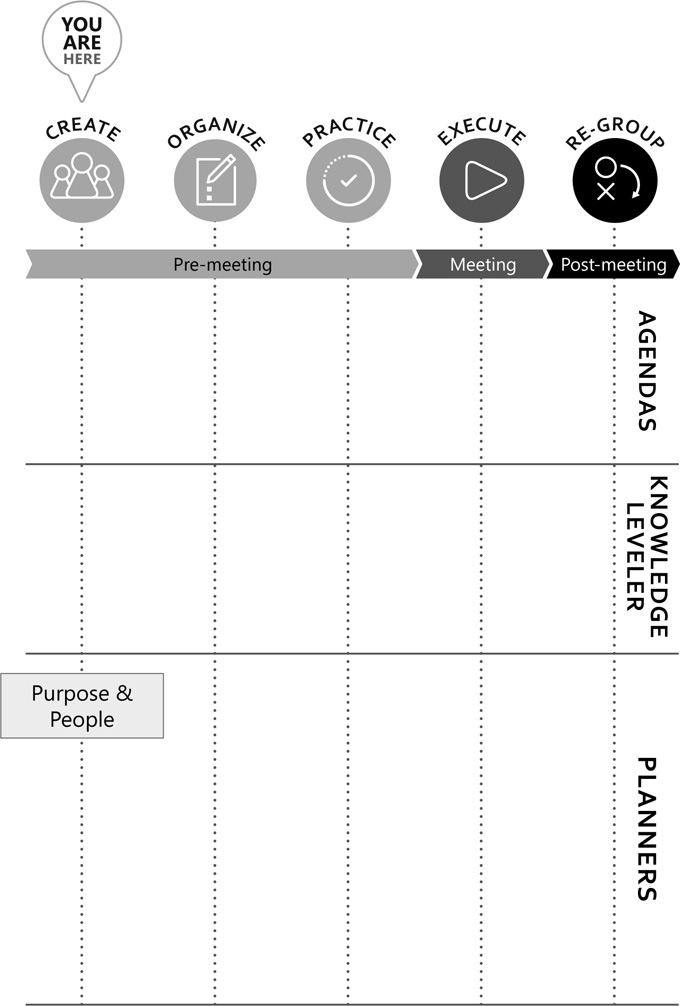

FIGURE 7.1 Create Stage of a Selling Squad

More is always better, right?

Earlier, you were introduced to the University of Washington men’s crew team. Coach Al Ulbrickson faced a classic leadership challenge: who should be on the boat? Each fall, more than 100 able-bodied undergraduates show up at the boathouse for tryouts. One of his first challenges was to push those students to their limits and find the best candidates for the university on the varsity, JV, sophomore, and freshman boats.

His next challenge was to find the right mix of eight men for each of the boats. Using size and strength as the criteria misses the X factor: the magic that happens in high-performing teams that allows them to produce a result that is greater than the sum of the parts. In rowing, the synchronicity that makes it seem as though the boat is flying over the water is called “swing.” (Brown, 2013, p. 275) In the years prior to the Olympic Games in Berlin, the coach made countless adjustments in the lineups for all four boats. He knew he had created the perfect combination when the eight men in the varsity boat began to beat the competition with a stroke rate that seemed much lower in contrast to the physical exertion of the rowers. They appeared to be rowing effortlessly.

As part of their reward for winning the national championships, they were given the opportunity to represent America at the games. As part of the Olympic competition, there were two rounds—a preliminary round and a medal round. After the preliminary round, the fastest boats from the preliminary round competed for gold in the next, medal round.

During the preliminaries, the Japanese boat quickly took the lead and rowed at a feverish 50 strokes-per-minute pace at its peak, splashing water everywhere. Team USA remained composed and found its swing at a much lower stroke rate in the low 30s, which allowed the Americans to methodically close the gap and seal the victory.

How did they do it? Every position in the boat certainly required a significant element of physical strength, endurance, mental fortitude, and excellence, but all elite rowers are strong and capable. This team of men learned to trust and care about one another so much that they would rather endure physical stress beyond their individual limits than let their team down. They were so deeply focused on one another as a collective unit that they were able to propel that wooden rowing shell as if it was a well-synchronized machine.

Think about those times that you were part of a selling squad that found its “swing.” How did that happen? It most likely wasn’t the four people who met for the first time in the parking lot, then, after some quick handshakes, walked into the customer’s office. Grouping together the most effective combination of people, rather than purely the strongest individuals, so that they can find their swing in high-stakes sales meetings is the fundamental challenge in creating selling squads.

Think back to a time when you were notified by a customer that your proposal was successful and you were invited to present to the committee as a finalist. You were elated. Think about the process you went through to decide who should join you at the pitch. You mentally scrolled through and chose from your database of trusted and credible colleagues who could potentially help you win this deal. You selected each person for a reason, for the contribution you hoped they would make to a winning effort. How much thought did you give to what they would be like to work with on this pitch, or how they would mesh with the others you asked?

Early in my sales career, I was asked to join a major pitch to a large university that had selected our organization as a finalist in a multiservice provider search. Our firm was at that time highly focused on cross-selling. So the lead salesperson dutifully matched the client’s various interests, as outlined in the request for proposal, with people from the firm that could address those needs, for a two-hour pitch. I was to represent one aspect of our capabilities. Members of our group were all arriving from different places for the pitch, so we were asked to meet in the hotel lobby at 7:30 that morning. It turned out that there were 12 of us, many of whom had never met before. And because of our numbers, the lead salesperson had arranged for a minibus to transport us from the hotel to the building where the presentation was to be held. Getting settled in the conference room was no easy task. There were six decision makers representing the university. Given the numbers and size of the conference room table, some of us were seated around the table but some had to take chairs against the wall. In the end, a few of us talked for about 60 seconds in the moments before the lead person wrapped up. In reality, two or three people from our group did the majority of the talking. We failed to win the business.

Based on what we’ve covered so far in this book, what went wrong? The opportunity was not fully qualified, and the salesperson glommed together 12 random people among whom there were varying degrees of established trust and credibility. For each of the 12 members of this group who committed to this presentation, there were substantial investments in preparation and travel time, in addition to the hard dollar cost of lodging and transporting each person to and from the pitch. You can imagine how that decision might have been made. “Gee, we don’t have much time and I don’t want to miss something. Better to be safe than sorry.”

What would have been a better approach?

It took Coach Al Ulbrickson at the University of Washington three years to assemble the winning formula for his eight-man varsity boat. And nearly a year for that crew to come together as a unit to find its swing. What would have been a better approach for the university pitch above?

Two fundamental questions face selling squad leaders after they’ve scored a vital meeting with a potential client: Who? and How many people should I bring? These decisions are often made with far too little thought. Conducting an effective and successful sales meeting is tough, even for a super seller who is 100 percent effective in a one-on-one meeting. What happens to sales effectiveness when the super seller adds senior managers, salespeople from other disciplines, subject matter experts, and technical experts—each of whom may be less than 100 percent sales-effective? And even if all meeting participants are at the extreme 100 percent effective, are you guaranteed that the collective unit will perform effectively? Without synchronicity or swing in your eight-man boat or on your selling squad, there is no magic and winning is an unlikely outcome.

Roles

Jon Katzenbach and Douglas Smith, former McKinsey partners and coauthors of both The Wisdom of Teams (1993) and The Discipline of Teams (2001), point out that high-performing teams are not “limitless groups of helpful people.” (Katzenbach & Smith, 2001, p. 96) They break down membership into four categories: core group, sponsor, ad hoc, and formal. (Katzenbach & Smith, 2001, pp. 94–95) For selling squads, I break this into three categories:

![]() Core group: These are the people who will be presenting at the sales meeting. This group includes those members essential for a successful meeting.

Core group: These are the people who will be presenting at the sales meeting. This group includes those members essential for a successful meeting.

![]() Extended group: This combines what Katzenbach and Smith call “ad hoc” and “formal” members. These are colleagues who contribute unique inputs to the group planning, practice, and follow-up efforts, but whose presence at the client meeting is not required. These people are the enablers who ensure that the core group accomplishes their mission at the pitch. Examples could include a product specialist who joins one of your prep sessions to share several industry and competitive insights or an associate who has committed to play an important role in pulling together presentation materials, coordinating technology, and lining up travel arrangements.

Extended group: This combines what Katzenbach and Smith call “ad hoc” and “formal” members. These are colleagues who contribute unique inputs to the group planning, practice, and follow-up efforts, but whose presence at the client meeting is not required. These people are the enablers who ensure that the core group accomplishes their mission at the pitch. Examples could include a product specialist who joins one of your prep sessions to share several industry and competitive insights or an associate who has committed to play an important role in pulling together presentation materials, coordinating technology, and lining up travel arrangements.

![]() Coach: This is someone who is able to contribute direction and feedback as needed by the team. This person should be available, objective, and skilled at coaching. He or she may be internal to your organization, such as a sales manager or practice leader. A sales coach can also be external—a professional like me, for example, whom your organization retains to support you or your selling team in your interactions before and after an important sales meeting or pitch.

Coach: This is someone who is able to contribute direction and feedback as needed by the team. This person should be available, objective, and skilled at coaching. He or she may be internal to your organization, such as a sales manager or practice leader. A sales coach can also be external—a professional like me, for example, whom your organization retains to support you or your selling team in your interactions before and after an important sales meeting or pitch.

How do you decide who should be on the core team and who should be on the extended team?

Core = critical to having a successful meeting

Extended = enables others to have a successful meeting

Once you have established the membership of your selling squad’s core group, it’s important to think through and define the role each member will play within that group. If roles are left undefined, people will sort themselves into the roles they seek or with which they are most comfortable; neither of which may suit your objectives as the leader of this unit.

So what roles, beyond the leader, need to be defined for a significant client, prospect, or partner meeting?

![]() Specialists: These team members bring deeper knowledge, beyond what the leader knows, to a client conversation. Choosing the specialist with the right experience and expertise will be an important factor in establishing credibility with your client. The specialist role can be played by subject matter experts (SMEs), business heads, or sales specialists in a specific area of capability. If they focus solely on their respective subject area, specialists risk coming across as arrogant and generic, and detract from your selling squad’s efforts. But, when properly prepared and aligned with the team, specialists can play a big part in helping your team win the business. (Chapter 13 has more on how to best leverage an SME in a sales meeting.)

Specialists: These team members bring deeper knowledge, beyond what the leader knows, to a client conversation. Choosing the specialist with the right experience and expertise will be an important factor in establishing credibility with your client. The specialist role can be played by subject matter experts (SMEs), business heads, or sales specialists in a specific area of capability. If they focus solely on their respective subject area, specialists risk coming across as arrogant and generic, and detract from your selling squad’s efforts. But, when properly prepared and aligned with the team, specialists can play a big part in helping your team win the business. (Chapter 13 has more on how to best leverage an SME in a sales meeting.)

![]() Technicians: These professionals have deep technical knowledge in a very narrow subject area, i.e., IT, systems specialists. The role you may want them to play in a customer meeting is to address your system’s ability to link with the customer’s or comply with certain protocols. Technicians can play an important part in forging connections with those stakeholders most focused on evaluating technical qualifications. The risk in bringing a technician is that either the question the person was brought to answer never comes up (projecting an image of inefficiency and overstaffing in your organization) or the person falls too far down the rabbit hole when addressing the question, taking valuable time and attention away from more relevant areas. Prepared properly, technicians can increase your firm’s credibility in a specific area and help the prospective client to check boxes in your favor on important questions that would not have been addressed otherwise by team members or in a follow-up discussion.

Technicians: These professionals have deep technical knowledge in a very narrow subject area, i.e., IT, systems specialists. The role you may want them to play in a customer meeting is to address your system’s ability to link with the customer’s or comply with certain protocols. Technicians can play an important part in forging connections with those stakeholders most focused on evaluating technical qualifications. The risk in bringing a technician is that either the question the person was brought to answer never comes up (projecting an image of inefficiency and overstaffing in your organization) or the person falls too far down the rabbit hole when addressing the question, taking valuable time and attention away from more relevant areas. Prepared properly, technicians can increase your firm’s credibility in a specific area and help the prospective client to check boxes in your favor on important questions that would not have been addressed otherwise by team members or in a follow-up discussion.

![]() Seniors: This executive is responsible for a business line or practice area, or may steer the overall organization as a partner or C-level executive. You hope this person will convey gravitas and client commitment. Your decision to include this person may be based on what you discovered about the seniority of client stakeholders attending the meeting, or what you feel needs to be conveyed in your team’s comments. Without clarity on their role in this group, seniors can take over as de facto leaders of your selling squad, both in preparation sessions and in the actual customer meeting. In doing so, they can take you away from an otherwise winning game plan. If passive, they can detract from your selling efforts by looking like an overpaid figurehead. Senior-level executives, positioned properly, can play a significant role in a winning selling squad effort and may allow your team to make great strides in differentiating your organization and value proposition. (Chapter 12 has an in-depth discussion on how to make the most of including a senior manager in a sales meeting.)

Seniors: This executive is responsible for a business line or practice area, or may steer the overall organization as a partner or C-level executive. You hope this person will convey gravitas and client commitment. Your decision to include this person may be based on what you discovered about the seniority of client stakeholders attending the meeting, or what you feel needs to be conveyed in your team’s comments. Without clarity on their role in this group, seniors can take over as de facto leaders of your selling squad, both in preparation sessions and in the actual customer meeting. In doing so, they can take you away from an otherwise winning game plan. If passive, they can detract from your selling efforts by looking like an overpaid figurehead. Senior-level executives, positioned properly, can play a significant role in a winning selling squad effort and may allow your team to make great strides in differentiating your organization and value proposition. (Chapter 12 has an in-depth discussion on how to make the most of including a senior manager in a sales meeting.)

![]() Juniors: This may be an analyst or internal salesperson on your team who you feel would benefit from the experience of attending an external client meeting. Juniors can also play an important role on-site at the customer meeting. For example, they could help you stay focused on client introductions and your opening comments by setting up the technology for a demo or presentation slides; they might also be able to assist you by taking primary responsibility for recording notes and coordinating any follow-up. Failing to clarify their role on the selling team could risk an improvised moment during a stressful juncture in the meeting, or their presence may simply distract the buyer.

Juniors: This may be an analyst or internal salesperson on your team who you feel would benefit from the experience of attending an external client meeting. Juniors can also play an important role on-site at the customer meeting. For example, they could help you stay focused on client introductions and your opening comments by setting up the technology for a demo or presentation slides; they might also be able to assist you by taking primary responsibility for recording notes and coordinating any follow-up. Failing to clarify their role on the selling team could risk an improvised moment during a stressful juncture in the meeting, or their presence may simply distract the buyer.

We will talk more about how to calibrate your core group with the right size and mix later in this chapter. For now, just take note that as you build out your selling squad, each member should have a clear role on the team. And although there is no requirement that you must always include a specialist, technician, senior, and junior, attaching a role to each team member will help you determine and describe your expectations for each person.

We’ve yet to define one role that’s key to the team’s success and which may be of particular interest to you. And that’s the role of the selling squad leader.

The Leader Role

High-performing teams have a leader. This section explores the qualities of effective team leadership for a team going into an important customer meeting. In following chapters, we will discuss activities on preparation, execution, and follow-up. Here, we will focus solely on qualities.

The leader of a selling squad establishes overall direction and purpose and facilitates discussion before, during, and after the meeting. For new business meetings, this role is typically played by a salesperson; for existing customer meetings, the leader may be the account manager.

Seniority in the organization is not essential; client knowledge combined with credibility and trust among her teammates are. On winning teams, this person is effective at generating ideas and discussion before the customer meeting, and skilled at managing the conversation during it. Harvard professor and expert on team dynamics Richard Hackman frames it this way in Leading Teams: “Those who create teams . . . have two quite different but equally important responsibilities: to make sure that the team has the best structure that can be provided, and to help members move into that structure.” (Hackman, 2002, p. 130)

I did some work with a salesperson from a large consulting firm that was getting organized for a big pitch, or what consultants call “orals.” This opportunity was connected to a project being done for a different division of a company that had been a client of this firm for many years. Firm leadership really wanted the work and was thrilled when its request for proposal response led to an invitation to present at orals. As in many professional services firms, the members of this group were a sharp bunch—recognized for their expertise not just within this firm but in the industries they serve. The salesperson was charged with organizing this group. He had a good track record of sales results but lacked the advanced degrees and technical experience that his group members brought. So how did he take on the leadership role? Because this opportunity had been green-lighted using the four Why’s to qualify covered in Chapter 3, he was able to prioritize this opportunity over others in his pipeline. This clarity also gave him confidence to spend extra time preparing for this role. I later learned that he dominated the decisions necessary to develop and coordinate the team’s work and discussions. During the pitch, everyone made the key points he had scripted for them, and everyone strictly followed the agenda the leader developed.

The salesperson was notified a few days following orals that his team had lost the business. Per the firm’s standard practice, they sent someone separate from the orals team to meet with one of the client stakeholders to get feedback on the presentation and their decision. In their internal debrief, the selling squad realized that there had not been much reaction or interaction from the client contacts during the meeting. Here’s what the client said in their feedback:

Your team had by far the most experience of any of the firms we were considering and, in fact, was the front runner going into the meeting. Your presentation was solid and everyone was impressed with how well prepared everyone was. At times, however, members of your team came across as arrogant and didn’t seem to interact as a team. Some of their comments were not connected to the things we are struggling with. And the business development person seemed to block his colleagues from going off script. In the end, your firm lost the business because, though you were qualified and well prepared, our buying team felt your firm would be rigid in its rules and tough to work with versus other options we were considering.

That feedback was shocking to some on the team. The team leader felt confused by this feedback. In our discussions afterward, he realized that, while he was better organized for this meeting than any other he had led, his increased focus on organization and details disconnected him from some of his teammates and what was actually happening during the client meeting.

He is not generally a command-and-control personality type, but he took on that persona during the team’s interactions. He came across as inflexible to his colleagues, and this pervaded how the team came across to the client. In conversations with individual group members afterward, some felt disengaged and that their ideas were not welcomed on how to make the presentation even better. That is one extreme—the command-and-control leader.

The other extreme is lack of leadership. If we took the same firm, same opportunity, and same group and made one change—exchanging the domineering leader for a weak one—you can imagine how that might have played out. The loudest voice might have won and brought the group down a different but equally fruitless path.

So what are the qualities of an effective leader of a selling squad? The most common responses I get when I pose this question to groups are: strong, charismatic, and resolute.

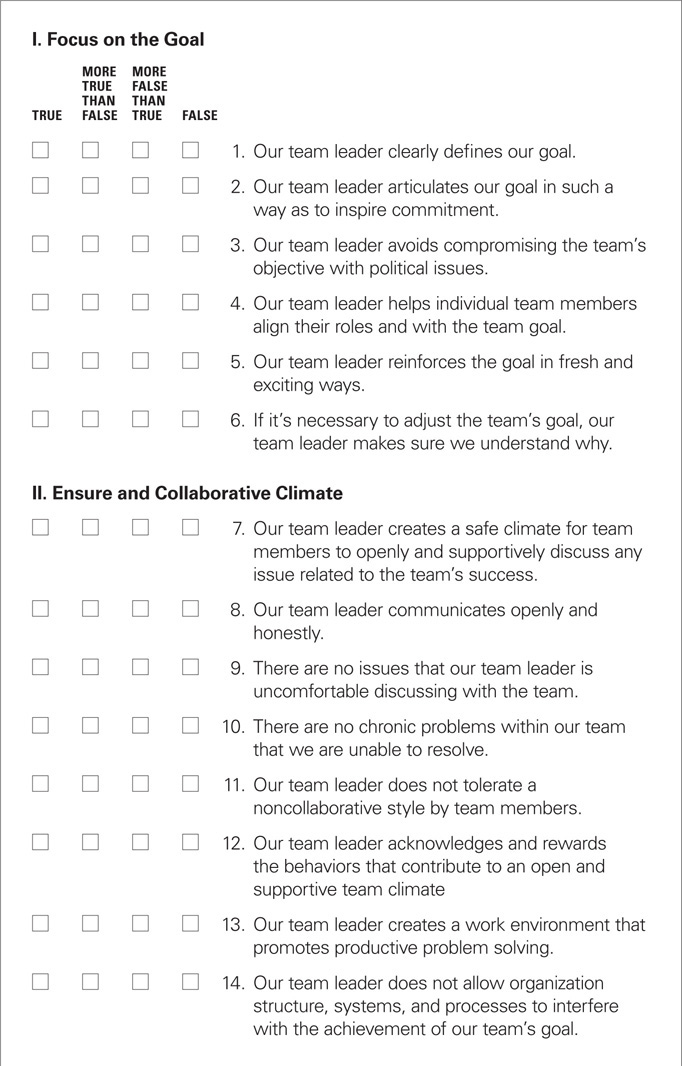

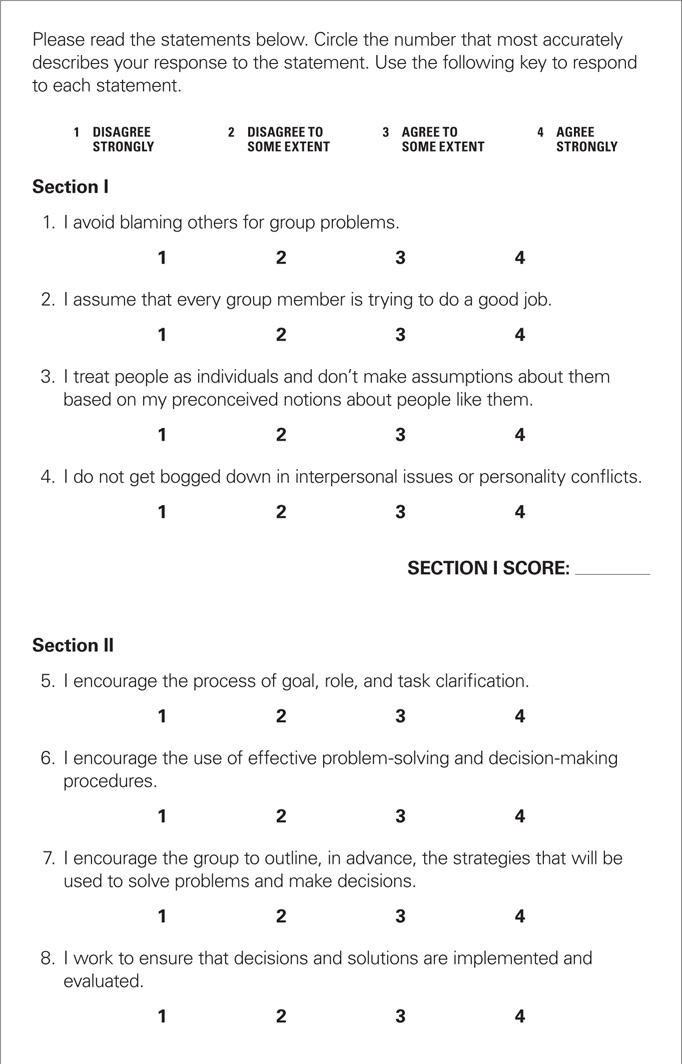

According to Susan Wheelan, author of Creating Effective Teams, “social scientists reject the notion of inborn traits” and, further, that a charismatic leader may actually “inhibit group progress and reduce member participation.” (Wheelan, 2010, pp. 77, 79) So if traits are not predictive, let’s look instead at behaviors. Frank LaFasto and Carl Larson, in their work covering 6,000 team members and leaders, offer an interesting view. They asked both work group members and leaders to define what they thought were the qualities of an effective leader. Leveraging this research, here are six best practices associated with effective selling squad leaders (LaFasto & Larson, pp. 98–149):

1. Focus on the goal: You must be able to communicate the collective goal so that it’s clear, meaningful, and current. If your team is preparing to go into an important meeting with an unhappy existing client, the goal may seem apparent—to retain the client. A collective goal is like a mantra, it inspires you and your team members. Think more broadly about the reasons that make retaining this client so important right now. What would success mean to us? Why is this critical to the firm? What are the implications if we are unsuccessful? Your performance goal might sound something like this:

Our goal is to hold on to this client for three reasons: (1) They are influential industry experts. (2) We want to position our company for a significant opportunity next year. (3) We want to shut down Competitive Industries’ efforts to take our turf.

Aligning strong, accomplished people in a group that may have never worked together before can be a steep challenge for selling squad leaders. As an effective leader, you should be able to keep the team members on task, despite many distractions, by inspiring them to stay focused on an important performance goal.

2. Create a collaborative climate: Organizational behavior researchers use word like open and supportive to describe leaders that drive collaboration. Create a space where information can flow freely and safely among individual members. Facilitate the production and communication of ideas in a way that surpasses what any one of the members could achieve on their own. Strive for equal contributions during core team discussions. In “The New Science of Building Great Teams,” MIT’s Dr. Alex “Sandy” Pentland discusses this notion of “equal talk time.” (Pentland, 2012, p. 68) This notion can be a powerful one in enabling selling squad leaders to talk less, facilitate more, and seek equal contributions from all members. Pentland employs a “big data” approach to assessing team communication patterns, collecting data on how often and for how long team members are communicating with one another, using electronic badges. (Pentland, 2012) Figure 7.2 shows the communications patterns for one geographically dispersed work team at the beginning and end of a week during the observation. The group’s members were shown updated maps daily that allowed them to grow more aware of and fix their communication biases. When you think about the selling squads you have led or contributed to, which of the pictures in Figure 7.2 would most resemble the communication pattern among members?

FIGURE 7.2 Mapping Communication Improvement

3. Build confidence: Communicate results in a way that is both fair and factual, and acknowledges member contributions. For complex, multidisciplinary, enterprise-wide new business pitches, there are countless things to be planned, practiced, developed, delivered, measured, and executed upon. In such instances, call attention to the progress that has been made, rather than endlessly focusing on what still needs to be done. This helps core and extended group members build momentum and stay on a winning course.

4. Demonstrate sufficient technical know-how: As a selling squad leader you don’t need to know everything, but you must have enough knowledge to be a credible member of the team, who can understand how and when to best leverage the team’s talents. How is your credibility with your fellow team members? Do you consider your role in customer meetings to be limited to bringing the pitch books, making opening introductions, and thanking the customer at the meeting’s close? Think about what skill and knowledge you bring to your selling squad in a winning effort. It might be your customer knowledge, your track record at delivering for the customer, or your skill at coordinating the team’s efforts. It’s important to recognize that you need your fellow team members, just as much as your team needs you, to win.

5. Set priorities: As your team moves deeper and deeper into its preparation for a critical client meeting, keep the team laser focused on the goal (#1 above). As time passes and new information emerges, facilitate discussions that may restack the team’s priorities, so you can all reach your collective end goal.

6. Manage performance: In the context of a sales or client meeting, you may very well have no reporting authority over any of the team’s members. So how can you manage performance without a manager’s typical toolkit of performance evaluations, compensation, incentives, and promotions? Consider embracing and recognizing the contributions that bring the group closer to attaining its goal. Acknowledging individual contributions by team members and, where appropriate, informing their managers of how well their employees are doing, can be huge motivators.

What would your colleagues say about the qualities you bring to your leadership role? LaFasto and Larson assess the effectiveness of a team leader by surveying team members on each of the six criteria above. (LaFasto & Larson, 2001) (See Figure 7.3.)

FIGURE 7.3 The Collaborative Team Leader (Team Version)

Leverage the six best practices above to drive focus, collaboration, confidence, credibility, progress, and performance as the leader of your selling squads.

You’ve identified potential members of your selling squad, and are focused on how to lead the team effectively. Now, let’s begin to build your team.

How Many

Earlier in this chapter, you may recall that I recounted the story of a 12-person pitch to a large university for the management and administration of their endowment assets. The challenge the salesperson in that story faced is one that you may have encountered: How do you strike the right balance between being selective and inclusive? Remember that membership in your core group is selective; they are the people who must be at the customer meeting for you to win. Your extended team can be inclusive. Anybody who is able and willing to support and guide the core team is welcome to play an important role.

Katzenbach and Smith explain that a core group should contain a small number of members, “with complementary skills, who are equally committed to a common purpose, common goals, and a commonly agreed upon working approach, to all of which team members will hold each other mutually accountable.” (Katzenbach & Smith, 1993, p. 96)

Losing Free Riders

There have been many studies on the optimal size of work groups, though none specifically for a selling team. Many organizational behavior specialists refer to “The Ringelmann” effect to decide group size. Max Ringelmann was a French agricultural engineer in the early 1900s whose research was aimed at maximizing team productivity and minimizing what economists often refer to as “social loafing” or as the “free rider” problem. Rather than increasing with each addition to a team, productivity increases slightly at first, but ultimately decreases as members of the larger and larger group allow others to shoulder the work. When my daughter, Melissa, was young, I coached her basketball team. She was a talented, focused, and very competitive young athlete, and would often carry the team. The more the other girls realized how Melissa could take over the game and lead them to victory, the more they allowed her to take control. At one point, it became a team of one with multiple free riders. Wheelan put it best: “successful teams contain the smallest number of members to accomplish goals and tasks.” (Wheelan, 2010, p. 47)

Less Is More

Sometimes more can produce less, and less can produce more. A selling squad’s core team should include only those members who will play a material role and whose presence is required to accomplish the team’s goals—whether that is to win the business, to secure another meeting, or to successfully renew an agreement. Effective selling squad leaders are aware that each person added to the core team changes the unit’s chemistry and can make the collective tougher to manage. Remember stacking blocks as a child? You and your siblings or friends would take turns adding a block creating a bigger and bigger tower until it finally collapsed and crashed down. My housemates and I, during our junior year as undergraduates, played a similar game with dirty dishes in the sink. Whether we’re talking about stacking blocks, dirty dishes, or selling squads, the principle is the same. Think carefully about the impact of each addition when you assemble your selling squad—will they strengthen the group or cause it to crumble?

Also, consider what messages the size of your group conveys to customers. Large groups can give the impression of low confidence, limited knowledge per person, bloated fee schedules, and confusing contact points. And outnumbering customer stakeholders can be intimidating to the client, which works against the type of free-flowing dialogue you know reflects an effective sales meeting. On the complete opposite end of the spectrum, showing up alone to a meeting with multiple buyers gives off the impression of overconfidence, and conveys that the person has little influence with his or her colleagues, that this business venture is a low priority, and that your company lacks the means to obtain needed resources.

Do the Math

Between those two extremes, how many people should attend your sales meeting? Let’s look at it from another angle. Think about how much time has been allotted by the customer to your team for this meeting. We can use a simple example of a 60-minute meeting or presentation, with three client stakeholders attending. If we assume that to be successful the client should be talking at least 50 percent of the time, that leaves your team with 30 minutes of talking time to allocate. This includes not only items on the agenda, but also time needed to respond to customer questions.

If you’re a math geek, you might want to play with the following formula:

N = 0.5 × T/P

Where:

N = number of team members

T = total time slot for pitch, meeting, or call

P = amount of talk time per selling squad member

I feel compelled to say that I developed this formula based on my experience building and coaching selling squads. This formula has only been validated by me as a sales geek and coach. I’ve found that doing the math helps teams focus their attention on answering “how many” before “who,” and to start their discussion with a solid benchmark. Starting with the “who” question can burn a lot of time on unnecessary back and forth about who did or didn’t do what at this or that sales pitch.

If you assume P = 15 minutes/person, the formula can be simplified to:

N = 0.033 × T

Road testing this formula with a 60-minute meeting (T = 60), N = 0.033 × 60 = 2. Changing P from 15 to 10 minutes per person would change the factor in the simplified formula from 0.033 to 0.05 and change your answer from two people to N = 0.05 × 60, or 3 people. In terms of the visuals, this matches up nicely with the three customer stakeholders.

Remember that 12-person university pitch I participated in and mentioned earlier? Let’s do the math on that two-hour presentation. So breaking down 60 minutes of talk time for our team, shared by 12 people, leaves five minutes per person. Hardly enough time for anyone to make a meaningful contribution. The formula above suggests four to six selling squad members.

How would the math have worked out for your last selling team meeting?

In meetings where the customer group is larger, things get trickier. Effective sales meetings are those in which stakeholders are engaged. And, if they are engaged, that means they are talking. The more talk time they use, the less you and your team will have. That means even fewer members, and a tougher call on who goes as part of the core team and who stays behind.

Who Goes?

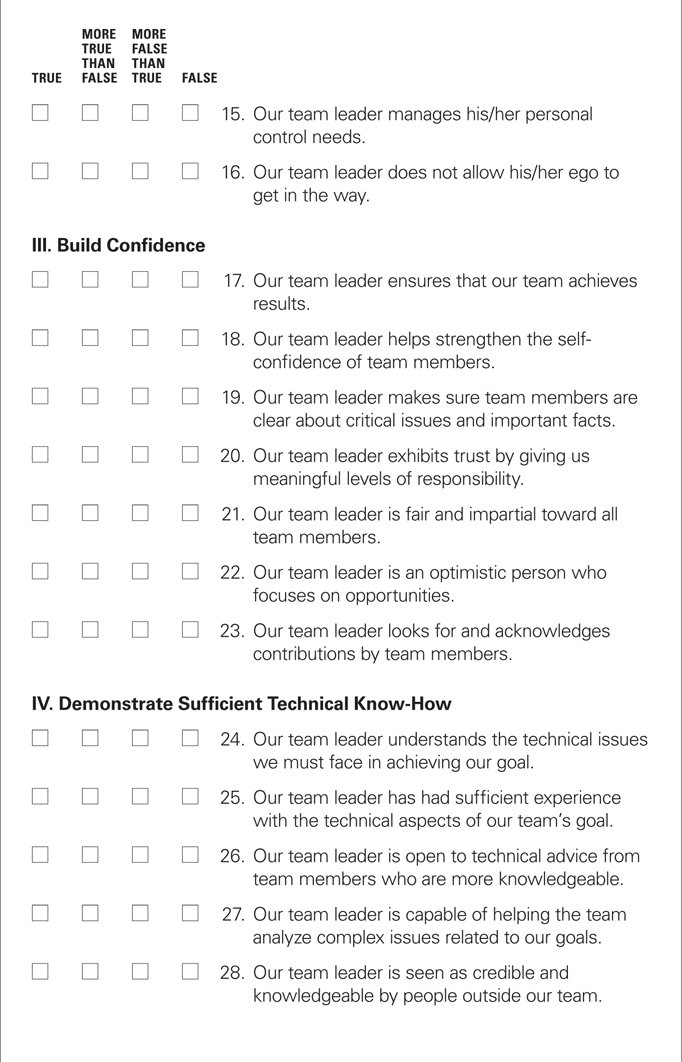

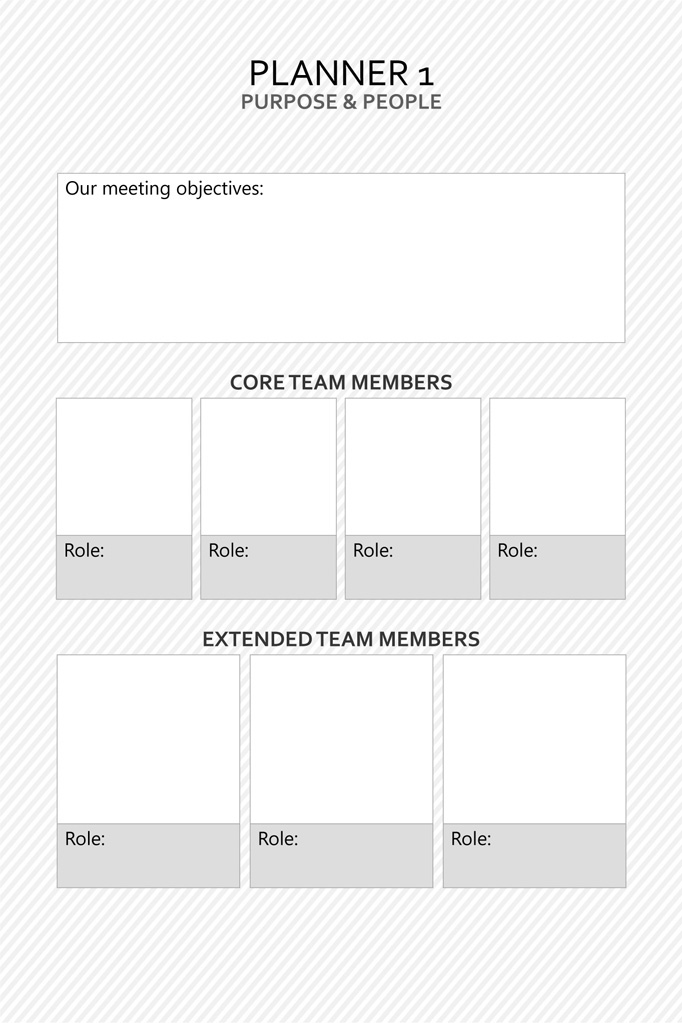

So far in this chapter, we’ve covered the components of a selling squad (core, extended, coach) in an effective work group. We’ve also talked about the different potential roles within your core group (leader, specialist, technician, senior, junior), and the implications of group size. This still leaves open the question of exactly whom you should include on your selling squad. (See Figure 7.4.)

FIGURE 7.4 Planner 1: Purpose & People

Many salespeople, once they have successfully scheduled an important meeting, begin pulling in bodies for the effort. Out of habit or routine, can you think of times you turned to some or all of the following?

![]() A-listers: Colleagues and partners who have a reputation for being big hitters and client friendly. They are frequently asked to participate in big meetings and have been connected to blockbuster wins.

A-listers: Colleagues and partners who have a reputation for being big hitters and client friendly. They are frequently asked to participate in big meetings and have been connected to blockbuster wins.

![]() Big guns: Senior leaders, including those from the C-suite (to show “senior management commitment”) and celebrity thought leaders to bring some star power to the event.

Big guns: Senior leaders, including those from the C-suite (to show “senior management commitment”) and celebrity thought leaders to bring some star power to the event.

![]() I-dotters and T-crossers: Specialists to answer every possible question that stakeholders may ask. You know, just in case.

I-dotters and T-crossers: Specialists to answer every possible question that stakeholders may ask. You know, just in case.

![]() Friend zone: People you like.

Friend zone: People you like.

![]() The swarm: The shock-and-awe strategy, showing all—literally all—of your resources.

The swarm: The shock-and-awe strategy, showing all—literally all—of your resources.

You may also have fallen into the common trap of passing over someone with a quieter personality who, despite not commanding attention the way an A-lister or big gun might, could have made significant contributions to your extended or core group.

Just like military maneuvers call for situational awareness, the same is true in building the membership in your team. There is no single approach that works in every instance, and, truly, there is merit in each of the above approaches. Being successful, senior, smart, or likeable doesn’t necessarily make someone right for you as the leader, for your team as a whole, for your customer, and for this particular opportunity or meeting.

Sometimes your partners are predetermined by your organization, but often this is your call.

For your next sales meeting with multiple stakeholders, what if you paused before immediately turning to an A-lister or big gun? High-impact selling squads, as you have come to appreciate, are not random groups of smart people who magically show up at go-time and shine. They are thoughtfully constructed teams that work to get in sync so that they can sell. If you are aiming to put together a selling squad that finds its swing at an all-important customer meeting or pitch, what qualities would you seek in colleagues that will collaborate not just during, but before and after, an important sales meeting? Consider looking for the following qualities when determining who you should ask to join your selling squad:

1. Interpersonal skills: This goes beyond whether someone can put together and speak in complete sentences. In their research of 6,000 workplace team members and leaders, LaFasto and Larson found that effective team members were not only technically competent. They exhibit four qualities: openness, supportiveness, an action orientation, and positive personal style. (LaFasto & Larson, 2001, pp. 9–25) Viewed another way, each person you add will contribute to or take away from your efforts to win the business. Beyond their smarts, what will it be like for you and the other group members to work with them in the lead up to and the execution of an effective client meeting?

2. Complementary skills: Author and Harvard professor Hackman conducted decades-long research on high-performing small groups in business and nonbusiness settings. He found that among the biggest mistakes in selecting team members was little to no attention paid to diversity. (Hackman, 2002, pp. 123–125) Homogeneous groups can be fun and get through meetings quickly because there are no conflicting ideas. It’s that same expediency that can create huge gaps in the team’s work. Diversity of thought, including a devil’s advocate, can feel inefficient at times. However, it’s the inevitable push and pull that can call out missed opportunities and unleash the sort of creativity that transcends what each member could produce individually. So consider what each candidate for your group would bring to the collective effort that’s different in terms of skills, knowledge, and experience.

3. Client-specific expertise: When a buyer invites you to present, it is safe to assume they feel your organization has the general qualifications to perform the work. Client-specific expertise refers to someone’s knowledge about a client. Heidi Gardner, in a Harvard Business, reported her findings from a multiyear study of 78 audit and consulting teams in two separate professional services firms. She distinguishes between “general professional expertise” (subject matter knowledge) and domain-specific expertise (knowledge about a specific organization or client). (Gardner, HBR, p. 80) When faced with performance pressure, such as in a high-stakes meeting or pitch, she found that groups tend to favor the input of those with general subject matter knowledge (the tried and true) over those with customer knowledge. But it is customer knowledge that allows a team to customize the design of solutions and how they are presented in a high-stakes meeting.

Have you ever seen leaders exclude from a selling squad people with exceptional client knowledge and a willingness to participate? I have. It can be done for reasons of ego, convenience, or to keep the group like-minded. And I cannot remember a time when such a decision produced anything other than a loss. The more client knowledge to be leveraged by your team before and during the pitch, the better.

4. Collective intelligence: Groups operate as a unit with a level of intelligence. This collective intelligence can be measured and used to predict success. The more experts you add, the better . . . right? According to work published by Dr. Anita Woolley of Carnegie Mellon University, and several co-authors, in Science in 2010, the intelligence scores of individuals were not significantly correlated with the group’s collective intelligence. What was? Among the factors: social sensitivity of group members and (sorry, fellas) the proportion of females. (Woolley, et al, 2010, pp. 686–688) Think about how potential group members who bring strong social intelligence (i.e., insight, empathy, etc.) will benefit your team’s decision making, both in its preparation and during a pivotal client meeting.

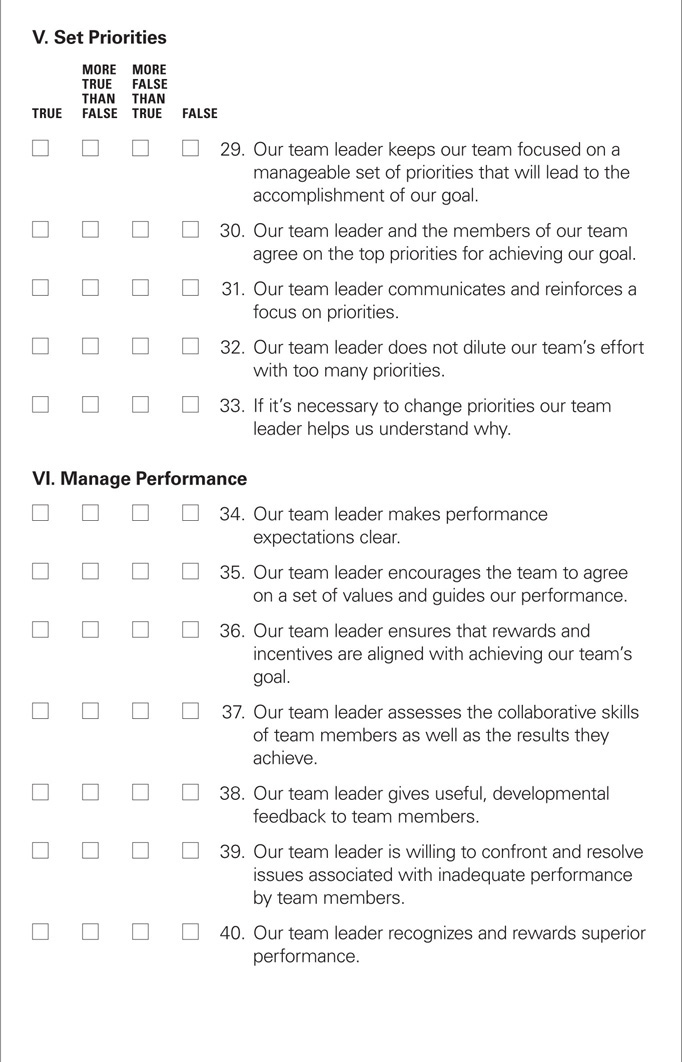

Figure 7.5 is an Effective Member Checklist used by researcher Wheelan. It will help you assess how well team members will assist with coordinating and facilitating group efforts, how frequently they will volunteer to take on tasks, and how willing they will be to bring full engagement to team interactions.

FIGURE 7.5 Effective Member Checklist

In my experience, the most effective selling teams are able to see each other— despite organizational hierarchy, siloes, or roles—as peers, or teammates, for the purposes of a meeting or pitch. Organizational reporting lines may feel significant to you and your team members since you are employees of that company. Reporting lines, however, have little use to clients. They are most likely seeking help to solve a problem that will help them accomplish their own goals. They are trying to see whether your organization is the one to do that. The pitch is your opportunity to demonstrate this. How your team interacts with the client and with one another conveys more than your words will. The process for being able to demonstrate this in front of a client begins far before the meeting. Set a standard for equal partnership among team members, and seek to address quickly any team member expectations for preferential status.

Recruiting

Sometimes the most valuable teammates need to be convinced to join your cause. And that can feel frustrating, especially when time is short and a big sale is on the line.

It is easy to fall into the trap of making one or more of the following assumptions about potential members of your selling team as you begin the recruiting process:

![]() They care about winning the deal as much as you do.

They care about winning the deal as much as you do.

![]() They see things exactly as you do.

They see things exactly as you do.

![]() They like you and trust you.

They like you and trust you.

![]() They should sign on since you’re all part of the same company.

They should sign on since you’re all part of the same company.

![]() They see a return on their investment (ROI) in working with you on this pitch or meeting.

They see a return on their investment (ROI) in working with you on this pitch or meeting.

As with any assumption, the facts may be quite different. A potential candidate may be hampered by time constraints, competing priorities, and perhaps even their own lack of confidence in their sales or presentation skills. Much as they might like to help, they may feel their time is better spent in other areas, especially given the time it takes to prepare for and travel to and from a customer meeting. If past work together has yielded no positive results, it is possible they see little, or even a negative, return in investing time in your selling effort.

Successfully persuading prospects and clients to take action requires a solid selling process and skills. The same process and skills can also be leveraged in recruiting colleagues to your selling team. Here are some reminders and best practices:

1. Know where you stand: Before asking for anything, it serves you to know where you stand with your colleague and deal with facts, not assumptions. Remember that the foundation of an effective team selling is mutual trust and credibility. If you’re not sure where you stand with a potential candidate, find out. Because even if the answer is no on this pitch, you may want to take actions that lay the groundwork for a yes on future ones.

2. Convey the mission: This connects back to the performance mission, goal, or mantra that you use to inspire your selling squad. Link your task to the work you have done to qualify this opportunity. Understanding what makes this opportunity real, winnable, and worthwhile to pursue will put conviction behind your recruiting pitch.

3. Connect to their ROI: In what way will their participation help accomplish their own objectives? As mentioned earlier, investing time and investing early in these relationships helps you understand how your sales opportunity aligns with their own goals.

4. Ask: Just as any effective sales meeting ends in an ask, in your recruiting pitch you need to ask for their participation if you want it. Remember you are not looking for people who will only show up at go-time, pull the cord on their back, and play a canned recording. The commitment you are seeking is to the mission and to become part of a group that, through its work together, will become an effective team for a critical customer meeting. How comfortable are you seeking such a commitment? Here is an example of what that might sound like:

As you may know, we are meeting with ACME Pellets in three weeks to retain their business. There is even more on the line, with a significant enterprise-wide sales opportunity coming up next year, and Competitive Industries trying to break into our space. Your participation on the team for this meeting will convey ACME’s importance to our company and position us as a solid partner both for the existing business and the future opportunity. So that you can make an informed decision before joining us, this team is investing time in preparing together to demonstrate during the meeting the teamwork our company is known for. Will you join us?

Take the time to sort through, practice, and even get feedback on how you will ask.

5. Go live: It’s way easier for someone to say no to a text, e-mail, or voice mail. In addition, think of how insignificant your request seems when it’s made with a few keystrokes or words on a recording. If it’s feasible, go see them and ask them to join you. If that’s not possible, schedule phone time, so that you can review the opportunity fully.

In a perfect world, people in your own organization should make themselves available to you whenever you need them. As a salesperson who has likely encountered rejection at least once in your life, you probably have come to realize that the world is imperfect. You’ve qualified this opportunity. You’ve given thought to the size of your team, and who the best candidates for each role could be. Take the steps above, find your conviction, and deliver your most compelling recruiting pitch so that you can put together a selling squad that wins the work.

As a reminder, Figure 7.6 is the tool to leverage during the Create stage of the selling squad Build Process.

FIGURE 7.6 Create Tools