In his book, Team of Teams, (Ret.) General Stanley McChrystal talks about how the military structure in Iraq had to adapt to a decentralized enemy in Al-Qaeda. This involved not only the creation of cross-functional units that could be deployed (teams). It meant that the command structure also needed to be cross-functional (team of teams). (McChrystal, 2015)

Selling organizations clearly are different from military organizations whose aim is to vanquish an enemy. The crossover point between General McChrystal’s team of teams approach and selling squads is that conditions required a change in strategy (Part I of this book), and that groups that had previously eyed each other with suspicion were forced to find ways to work together effectively in smaller units to accomplish the broader mission (Part II of this book).

In this chapter of Part III, we begin to talk about what barriers to collaboration may exist in your organization. And how you can create change in order to drive better teamwork so that you can win more significant opportunities.

You may be aware of many barriers in your organization that prevent the kind of collaboration we have been discussing in this book. In a New York Times interview, Lars Dalgaard, general partner of the $4 billion venture capital firm Andreesen Horowitz, was asked about what he looks for in a company’s culture. His response was, “If you can get organizational siloes to talk to each other, then you can have power in your organization.” (Bryant, 2015) If you could find ways to remove these barriers, how much easier, more fun, and more effective would it be to build excellent selling squads?

If you’re a senior leader or sales manager, we will talk in this chapter about some of the ways you can begin changing your organizational setting to facilitate the sort of teamwork that produces better selling squad performance. Doing that sets the stage for more effective cross-selling and enterprise-selling.

If you’re a salesperson who leads or contributes to selling squads, we will cover actions you can take starting today that will begin changing the type of collaboration you experience.

Barriers to Cross-Organization Collaboration

To set the proper context for all of these ideas, it’s important to first understand what you’re up against by identifying the barriers commonly faced by leaders and salespeople.

Imagine this . . .

Your organization has successfully executed its business plan and grown dramatically, and it now encompasses more than 20 lines of business, solution areas, or disciplines. You hear about the importance of cross-selling and, in fact, it is one of the metrics against which you will be measured next year. You also feel the pressure to drive revenue to higher and higher levels as your company recovers from the financial crisis and must show returns on the investments it has made in building out new business lines —through talent and business acquisitions. People from other areas of the business are feeling the same pressure, as you are deluged by calls to gain access to several of your clients and people you know well. And those are the cordial ones.

Maybe the more aggressive salespeople from other parts of your company show little regard for connecting with you and learning about the client relationship you have built and instead, contact the company directly, which in your opinion, hurts your own credibility as well as the firm’s. It may feel like anarchy at times. With the firm’s larger clients, or key accounts, your organization may have put together account planning “teams.” These groups are large, especially for the best client relationships; and the discussion is probably focused on completing a template for senior management and ensuring that all possible products or services that could be sold to them are included. When asked, you may have tried your best to coordinate introductions between your colleagues from other disciplines and the right people at the client company. In the process, you may also discover that your colleagues seem to have some widely different ideas about sales process and execution. As a result, these introductions tend not to go very well or far beyond that first meeting. You’re not sure what to do.

That scenario reflects what often happens when an organization finds its own structure to be out of sync with its desired behaviors. In this case, as the account manager, you sincerely desire to do the right thing and have the capability and interest to lead an effective account team. Yet, you may find yourself surrounded by disjointed energy and activity.

In my research, coaching work, and experience, there are a number of common barriers to building effective teamwork among account teams reflecting different product or practice areas within the organization and across different functional roles. They all branch off the same issue: organizational structure. In fact, consultants Baker Tilly published a 2014 white paper in which the authors posit that “siloed structures are inherent in many organizations and are not conducive to effective collaboration and cross-selling.” (Hanson, et al., 2014, p. 2)

Lines of business or practice areas may be a logical and efficient way to manage the enterprise. Before we discuss the various ways that you can drive collaboration, consider the ways in which silos impede teamwork among different departments:

![]() Wide spectrum of sales effectiveness: Talent recruiting and development is left by many organizations to their various divisions. This enables leadership at the divisional level to decide the types of skills, behaviors, and experiences they seek in candidates. This structure also allows decisions to be made on what type of development, if any, is needed within that part of the organization. It is not hard to imagine that, across divisions, there exist different philosophies about selling and client-facing activities, among other things. One division believes in the star producer model and that the best thing management can do is get out of the way so this division can close deals. Another line of business believes that sales is process driven, and rallies around a sales process, best practices, and skills training. To the extent that divisional leaders disagree on the value of teamwork and collaboration, one can easily see how two people from different lines of business within the same organization can arrive at the same meeting with conflicting ideas about how it should be managed.

Wide spectrum of sales effectiveness: Talent recruiting and development is left by many organizations to their various divisions. This enables leadership at the divisional level to decide the types of skills, behaviors, and experiences they seek in candidates. This structure also allows decisions to be made on what type of development, if any, is needed within that part of the organization. It is not hard to imagine that, across divisions, there exist different philosophies about selling and client-facing activities, among other things. One division believes in the star producer model and that the best thing management can do is get out of the way so this division can close deals. Another line of business believes that sales is process driven, and rallies around a sales process, best practices, and skills training. To the extent that divisional leaders disagree on the value of teamwork and collaboration, one can easily see how two people from different lines of business within the same organization can arrive at the same meeting with conflicting ideas about how it should be managed.

![]() Different P&Ls: One of the greatest levers a leader can pull is that of his or her budget. Allowing budgets to be created and managed by divisions gives each leadership team the ability to use resources as the team sees fit given the division’s goals. So the budget is a reflection of the team’s beliefs about driving revenue and managing costs. Training budgets, typically part of divisional budgets, also allow skill gaps that exist between divisions to grow over time.

Different P&Ls: One of the greatest levers a leader can pull is that of his or her budget. Allowing budgets to be created and managed by divisions gives each leadership team the ability to use resources as the team sees fit given the division’s goals. So the budget is a reflection of the team’s beliefs about driving revenue and managing costs. Training budgets, typically part of divisional budgets, also allow skill gaps that exist between divisions to grow over time.

![]() Divergent access to technology, information, and tools: Sitting in the present day, think about how networked you are personally and professionally, how much more quickly information flows to and from you compared to even 10 years ago. There has been tremendous adoption of customer relationship management (CRM) platforms and, with them, far greater ability for information sharing and analytics. Now what if, say, one line of business religiously uses a CRM and its people are well networked within their own division. Yet the information sharing does not go beyond this division to and from the company’s other lines of business. Even with an enterprise-wide platform, information gained by one division may not be shared when different parts of the business pressure to compete rather than collaborate with one another. How would these types of scenarios impact selling squad collaboration before and teamwork during a customer meeting? In fact, Salesforce, in its “2015 State of Sales” research study, surveyed more than 2,300 global sales leaders across industries. Among their findings was that high-performing organizations are three times more likely than underperformers to view sales as an organization-wide, rather than an individual, responsibility. (Salesforce, 2015)

Divergent access to technology, information, and tools: Sitting in the present day, think about how networked you are personally and professionally, how much more quickly information flows to and from you compared to even 10 years ago. There has been tremendous adoption of customer relationship management (CRM) platforms and, with them, far greater ability for information sharing and analytics. Now what if, say, one line of business religiously uses a CRM and its people are well networked within their own division. Yet the information sharing does not go beyond this division to and from the company’s other lines of business. Even with an enterprise-wide platform, information gained by one division may not be shared when different parts of the business pressure to compete rather than collaborate with one another. How would these types of scenarios impact selling squad collaboration before and teamwork during a customer meeting? In fact, Salesforce, in its “2015 State of Sales” research study, surveyed more than 2,300 global sales leaders across industries. Among their findings was that high-performing organizations are three times more likely than underperformers to view sales as an organization-wide, rather than an individual, responsibility. (Salesforce, 2015)

![]() Competing goals: Across different organizational siloes—whether they be by discipline or by functional role—objectives are set to advance their goals. Those objectives generally flow down the reporting lines and into performance goals, against which individuals are evaluated and compensated. What if the performance goals differ across divisions, as they likely will? What if one division, which has set enterprise-selling as a target, includes teamwork as a qualitative component in performance reviews, while another division sets goals that exclude any mention of team-based, cross-discipline, multiproduct, or cross-selling activity? Consider how that impacts a selling squad leader in recruiting group members and turning them into a team for an effective sales or client meeting.

Competing goals: Across different organizational siloes—whether they be by discipline or by functional role—objectives are set to advance their goals. Those objectives generally flow down the reporting lines and into performance goals, against which individuals are evaluated and compensated. What if the performance goals differ across divisions, as they likely will? What if one division, which has set enterprise-selling as a target, includes teamwork as a qualitative component in performance reviews, while another division sets goals that exclude any mention of team-based, cross-discipline, multiproduct, or cross-selling activity? Consider how that impacts a selling squad leader in recruiting group members and turning them into a team for an effective sales or client meeting.

Matrix reporting lines can represent even greater confusion for individual team members. When the multiple masters they serve harbor different goals, they must reconcile them in choosing how to structure their activities.

![]() Varied geographies, culture, and language: Think about the many ways in which organizations deploy their sales, marketing, and support resources. Certain functions may be centralized, others distributed. Especially after the most recent economic crisis in 2007–2008, many organizations worked to protect their profit margins by redefining roles and avoiding—or at least minimizing—duplication of resources. This experience also refocused many companies on driving revenue from more sources. This caused many companies to expand distribution into new channels and new geographic markets. For an intact team all located in the same office, this is tough enough to pull off. When resources are distributed, think about how much harder it has become to assemble a team—keeping up with all the capabilities you need, finding people whom you can partner with, and then pulling them together onto a selling squad. You must now be able to factor in and navigate around a higher cost of sales, greater travel time, and higher communication barriers.

Varied geographies, culture, and language: Think about the many ways in which organizations deploy their sales, marketing, and support resources. Certain functions may be centralized, others distributed. Especially after the most recent economic crisis in 2007–2008, many organizations worked to protect their profit margins by redefining roles and avoiding—or at least minimizing—duplication of resources. This experience also refocused many companies on driving revenue from more sources. This caused many companies to expand distribution into new channels and new geographic markets. For an intact team all located in the same office, this is tough enough to pull off. When resources are distributed, think about how much harder it has become to assemble a team—keeping up with all the capabilities you need, finding people whom you can partner with, and then pulling them together onto a selling squad. You must now be able to factor in and navigate around a higher cost of sales, greater travel time, and higher communication barriers.

![]() Different rewards: Across the enterprise, there may be wildly different ideas about how rewards should be structured. Rewards could be financial and be reflected in the form of a compensation program design, or even nonfinancial, including what behaviors are acknowledged. Compensation consultants ZS Associates reflected on their work in developing more than 700 sales force compensation plans and found that “when poorly designed or implemented, these (incentive compensation) models can result in dramatically inflated cost of sales, destructive conflict between team members, weakened accountability for results and high levels of customer confusion.” (Moorman & Albrecht, 2008, p. 33) They explain that a poorly designed comp program cannot counter “tension regarding what is the right customer solution, who has decision authority and who should be involved in a given opportunity.” but instead leads to suboptimal outcomes all around. (Moorman & Albrecht, 2008, p. 34) Yet, many leaders over-rely on their comp program and hope that their teams will somehow find their way to collaboration and team selling success. Harvard professor Heidi Gardner, whose research focuses on professional services firms, feels that all of the following can discourage collaboration: commissions, producer recognition groups like “president’s club,” third-party star-ranking lists, and even what sales wins get the spotlight in firm-wide meetings and communications discourage collaboration. (Gardner, HBR, 2015, p. 78)

Different rewards: Across the enterprise, there may be wildly different ideas about how rewards should be structured. Rewards could be financial and be reflected in the form of a compensation program design, or even nonfinancial, including what behaviors are acknowledged. Compensation consultants ZS Associates reflected on their work in developing more than 700 sales force compensation plans and found that “when poorly designed or implemented, these (incentive compensation) models can result in dramatically inflated cost of sales, destructive conflict between team members, weakened accountability for results and high levels of customer confusion.” (Moorman & Albrecht, 2008, p. 33) They explain that a poorly designed comp program cannot counter “tension regarding what is the right customer solution, who has decision authority and who should be involved in a given opportunity.” but instead leads to suboptimal outcomes all around. (Moorman & Albrecht, 2008, p. 34) Yet, many leaders over-rely on their comp program and hope that their teams will somehow find their way to collaboration and team selling success. Harvard professor Heidi Gardner, whose research focuses on professional services firms, feels that all of the following can discourage collaboration: commissions, producer recognition groups like “president’s club,” third-party star-ranking lists, and even what sales wins get the spotlight in firm-wide meetings and communications discourage collaboration. (Gardner, HBR, 2015, p. 78)

![]() Inconsistent leadership messages: Oftentimes, senior leaders want to forge change in how their organization collaborates to capture the benefits of team selling—including larger, cross-discipline mandates that carry a lower acquisition cost and better senior-level access. Yet, what gets communicated is at odds with the goal. John Kotter, Harvard Business School professor and author of Leading Change, has found that the majority of change efforts fail, largely due to inconsistent messaging and lack of leadership support. (Kotter, 2014)

Inconsistent leadership messages: Oftentimes, senior leaders want to forge change in how their organization collaborates to capture the benefits of team selling—including larger, cross-discipline mandates that carry a lower acquisition cost and better senior-level access. Yet, what gets communicated is at odds with the goal. John Kotter, Harvard Business School professor and author of Leading Change, has found that the majority of change efforts fail, largely due to inconsistent messaging and lack of leadership support. (Kotter, 2014)

So how do you get beyond these obstacles in trying to win more consistently when selling squads are the required path to get you there?

Organizational Climate

The research on high-performing teams is unequivocal: the organizational setting in which teams perform is a major factor in going from group to team. It is what Susan Wheelan calls “organizational support” (Wheelan, 2010, p. 2), what Richard Hackman refers to as the “enabling structure” (Hackman, 2002, p. 93), and what LaFasto and Larson label the “the organizational environment.” (LaFasto & Larson, 2001, p. 157) Boston Consulting Group, in its white paper “The Three Golden Rules of Cross-Selling,” state their position that “the fundamental driver of cross-selling is getting the organization right.” (Cainey, et al., 2002, p. 1)

As I share some ideas for you to consider in your own organization, I will group them into those that apply to leaders in considering top-down adjustments; and those that can be leveraged by selling squad members—team leaders, subject matter experts, and even extended group members—to modify their own actions from the bottom up within the organization.

For Senior and Sales Managers

Let’s start organizationally from the top down. Getting the organization right, to use Boston Consulting Group’s phrase, involves looking at three components—communication, coaching, and compensation—within your own organization to see if they are contributing to or detracting from your desire to facilitate better teamwork across your own organization—for the purpose of producing more effective cross-selling and, even further, true enterprise-wide or cross-discipline solutions for clients across your organization’s channels and geographical footprint. (See Figure 18.1.)

FIGURE 18.1 Three C’s of Building Organizational Collaboration

Communication

There are two components of management communication that I’d like to address here—from senior managers down into their groups, and for managers across the organization’s divisions, whether they be separated by product, business line, and/or geography.

Referring back to Kotter’s work on change leadership, if as a leader you strive for your organization to be among the minority that successfully creates change, what message you deliver, and how and when you communicate it, are all significant components. (Kotter, 2014) Communicating generic messages that vary by leader and seem to come and go with the wind conveys one thing quite clearly: whatever you are attempting to communicate is being received as not relevant and not important and will disappear as quickly as it arrived.

Asking managers and their people to change current behavior is big. People engage in their activities because they believe them to be—rightly or wrongly—linked to producing results and success. Operating in a way that differs from their current path is risky: it may not work, they may be embarrassed in front of colleagues, and they may fear failure, which could cost them compensation and even their job. One of the biggest mistakes I see leaders make in forging any change initiative—including to promote more teamwork—is to use what I like to call the Bruce Willis method of management communication: toss it like a grenade over the shoulder and walk away. Communicating the need for behavior change in individuals must be clear and compelling; connected to the organization’s goals, challenges, and initiatives; consistent within the team and across the organization; and specific to individuals. And repeating messages allows full absorption by the recipient.

Let’s unpack that. Messaging effectively requires empathy. Ernest Wilson III, dean of University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, states that empathy, compared to all the other leadership attributes most commonly cited in his research among business executives, was most important. (Wilson, 2015) Let’s play this out from the top down. This means that as the CEO, you are able to convey to your senior leadership team an understanding for their concerns about changing current practices; that your senior leaders are able to do the same within their own management teams; and that your first-line managers are able to empathize and message as well.

For a leader to be clear and compelling in his or her messaging sounds about as disagreeable as motherhood and apple pie could. What does it really mean? The message that begins with the CEO and flows down and across the organization is simple and important. This requires preparation, practice, and feedback to ensure that what gets received aligns with your intent. This transmits through your organization that regardless of what was understood in the past, it is no longer acceptable to act as a solo performer and sends the message that there is a new expectation of teamwork both within and across business lines.

Why devote space in your messaging to the organization’s goals, challenges, and initiatives? Two reasons: (1) this is another opportunity to remind people that there are goals, challenges, and initiatives; and (2) you set the context within which team-based selling is important. For example:

![]() Goal: “As you know, we are aiming to grow the organization organically by 10 percent over the next two years.”

Goal: “As you know, we are aiming to grow the organization organically by 10 percent over the next two years.”

![]() Challenge: “This is not going to be a cakewalk. Competition has grown in every direction, and we have several product gaps and deficiencies.”

Challenge: “This is not going to be a cakewalk. Competition has grown in every direction, and we have several product gaps and deficiencies.”

![]() Initiative: “This is why the leadership team has put together an initiative to promote and monitor cross-product collaboration across the organization.”

Initiative: “This is why the leadership team has put together an initiative to promote and monitor cross-product collaboration across the organization.”

The message must also be specific to the audience with whom you are communicating. This group might be large, as in the case of a companywide or national sales meeting; it might be a small group, as in the case of a specific team; or it might even be one person, as part of a scheduled one-on-one meeting. Regardless of the audience’s size, what is your ask? You may want people to work together differently, perhaps within their own selling squads, and maybe with others across the broader organization. Consider what success would look like for you. Perhaps it is people committing time, especially over the next 120 days, to prepare together longer and more intentionally. Maybe you would like to see people broadening their contacts by the end of this year across the company that will strengthen their solution set and increase the number of potential partners that can help craft, explain, and deliver solutions that cross organizational lines.

Effective messaging is also consistent. This means a few things. First, a similar version of the message that a manager hears in one part of the company squares with what a friend, who leads a team in another division, also hears. Second, it means that the message is repeated. It’s been said that for messages to be fully understood they need to be repeated five to seven times. Even if the team you lead is a group of brilliant PhDs in molecular biology, repeated messaging allows them to gain increasing focus as they filter out other thoughts, and be certain that this is one of those messages that is here to stay. Third, connected with your specific ask, check in consistently to seek among your leaders, managers, and individual performers evidence and examples of consistent, collaborative, and cross-organizational behavior change. What examples are they able to cite of selling teams preparing together differently? What evidence can they provide of meetings they have held with people outside their past internal network, and what commitments to collaborate were made?

The final component of communication is the action you take as a leader to facilitate collaboration on your team, with channel partners, and across the organization. These might include:

![]() A CRM tool deployed across the organization: Incomplete deployment limits communication and collaboration. If in your own little part of the world, you consistently communicate your expectation that people leverage the CRM tool that you’ve deployed, it will get used. With that as a starting point, there are a number of functionality tools within most CRMs that allow selling squads to effect knowledge leveling across their core or extended team colleagues, and to help bring others into the fold to advance existing opportunities, retain existing client mandates, and find and plan around new ones.

A CRM tool deployed across the organization: Incomplete deployment limits communication and collaboration. If in your own little part of the world, you consistently communicate your expectation that people leverage the CRM tool that you’ve deployed, it will get used. With that as a starting point, there are a number of functionality tools within most CRMs that allow selling squads to effect knowledge leveling across their core or extended team colleagues, and to help bring others into the fold to advance existing opportunities, retain existing client mandates, and find and plan around new ones.

![]() Bilateral networking events: Forging a relationship with another business line that you have done very little work with in the past offers benefits on two levels. On one level, it is an opportunity for you as a leader to model your request for new and better collaboration. It also provides a platform where your people can better understand another capability and become better acquainted with the people you would be partnering with. On the first point, a lunch-and-learn format is widely used to broadcast product or service type of information. In my experience, these events can succeed or fail based on the effectiveness of one sales rep who is delivering his or her standard internal cross-sell pitch. Consider partnering him or her with one or more people from your own team to properly prepare for the opportunity and to be sure comments are customized, including the benefits, to your team and the market you cover. You could also consider organizing a networking event, such as a happy hour that allows the individuals on your team to connect with one or more individuals on another team. Successful teams are built on a foundation of credibility and trust. Providing the platform for people to connect personally and professionally allows them to begin developing credibility and trust in one another. This is essential if they are going to consider entrusting each other with something as precious as an introduction to a client relationship they have built, in some cases, over many years.

Bilateral networking events: Forging a relationship with another business line that you have done very little work with in the past offers benefits on two levels. On one level, it is an opportunity for you as a leader to model your request for new and better collaboration. It also provides a platform where your people can better understand another capability and become better acquainted with the people you would be partnering with. On the first point, a lunch-and-learn format is widely used to broadcast product or service type of information. In my experience, these events can succeed or fail based on the effectiveness of one sales rep who is delivering his or her standard internal cross-sell pitch. Consider partnering him or her with one or more people from your own team to properly prepare for the opportunity and to be sure comments are customized, including the benefits, to your team and the market you cover. You could also consider organizing a networking event, such as a happy hour that allows the individuals on your team to connect with one or more individuals on another team. Successful teams are built on a foundation of credibility and trust. Providing the platform for people to connect personally and professionally allows them to begin developing credibility and trust in one another. This is essential if they are going to consider entrusting each other with something as precious as an introduction to a client relationship they have built, in some cases, over many years.

![]() Recognition: Be intentional with the success stories you broadcast to your teams in group meetings, in calls, or via other forms of communications. If you are messaging more teamwork but always seem to highlight successes that attach to one person, you can see how that can sabotage your own efforts for behavior change. Find small wins to start, and look for larger ones as they happen. Recognize these wins in team settings, being sure to discuss in advance with the people responsible for that win so that it is messaged in a way that works well for you both. And in one-on-one settings, be sure to acknowledge even unsuccessful attempts at new behaviors. Done properly, this rewards progress toward a desired behavior and, unlike changes to a compensation plan, is done easily and at no cost.

Recognition: Be intentional with the success stories you broadcast to your teams in group meetings, in calls, or via other forms of communications. If you are messaging more teamwork but always seem to highlight successes that attach to one person, you can see how that can sabotage your own efforts for behavior change. Find small wins to start, and look for larger ones as they happen. Recognize these wins in team settings, being sure to discuss in advance with the people responsible for that win so that it is messaged in a way that works well for you both. And in one-on-one settings, be sure to acknowledge even unsuccessful attempts at new behaviors. Done properly, this rewards progress toward a desired behavior and, unlike changes to a compensation plan, is done easily and at no cost.

How can a management team communicate a message consistently if it doesn’t agree as a leadership team in the substance of the message? As it relates to team selling, this could reflect different views on the importance of preparation, practice, post-mortems, cross-selling, enterprise-wide or cross-discipline solutions, training, one CRM, and so on. This is the point at which a management team shows whether it operates as a high-performing team or simply a group of individual performers. Among the many lessons in this book, consider how high-performing teams rally behind a unified performance goal and seek, not consensus, but rather how to work through conflict and to forge agreement, giving decision rights to those on the team who are best positioned to make that call. It is important to set time for the team to discuss and debate the topic, so it can get to a place of appreciation on the importance of better teamwork. This is not a “let’s all sit in a circle, join hands, and sing ‘Kumbaya’ activity” or a “fall backward and see if others will catch you exercise.” Rather, this is an important path to accomplish the management or leadership team’s mission. Expect conflict. Managers get to a position of authority based on the strong views they hold. Resolve these conflicts in private and seek unified commitment on the message as an outcome.

Coaching

After you communicated your message, you checked in for evidence and examples of take-up on your ask. Invariably there will be gaps between your expectations—what you thought you communicated—and the behaviors and activity you see. These gaps form the input for coaching, the second of the three C’s of setting an appropriate organizational climate. How do you do it effectively?

You know the story . . . as a mild-mannered sales manager, you have a one-on-one meeting with an ordinary sales citizen to check in on how this citizen has changed his or her process for creating and leading selling squads. A problem arises and—WHAM!—you make a beeline to the phone booth (yes, they still exist) and out comes super sales manager, complete with red cape. (Did you think superhuman abilities were limited to the super sellers we discussed in Chapter 1?) Faster than a speeding sales cycle, more powerful than a strong pipeline, and able to leap tall revenue goals in a single bound. In your rush to rescue Metropolis and solve the salesperson’s dilemma, however, you may not realize that this method of coaching for sales teams is not really coaching at all; it is kryptonite to your team’s performance.

Before we talk about how to properly provide sales coaching to a team leader or team, it’s important to be aware of several dynamics at play:

![]() Salespeople and selling teams come to you with a wide range of skills and talents. They know at least one thing far better than you do: themselves.

Salespeople and selling teams come to you with a wide range of skills and talents. They know at least one thing far better than you do: themselves.

![]() As a sales manager, you probably came to the position based on your success as a salesperson. You likely take pride in how you used to help clients. Now that you’re in a management role, you genuinely want to help your team by sharing with them your experience and insights.

As a sales manager, you probably came to the position based on your success as a salesperson. You likely take pride in how you used to help clients. Now that you’re in a management role, you genuinely want to help your team by sharing with them your experience and insights.

![]() How you “help” salespeople may create unintended consequences:

How you “help” salespeople may create unintended consequences:

• Being the superhero problem solver is not scalable, and leads to manager burnout.

• Solving the immediate problem, while expedient, makes your team dependent (rather than independent), reduces their sense of ownership, stunts their results and professional growth, and slows down the sales process.

Asking—rather than telling—takes patience and restraint, not natural strengths for most sales leaders. Effective sales managers realize that coaching for sales teams requires processes and skills that may be a departure from those you used in a selling role.

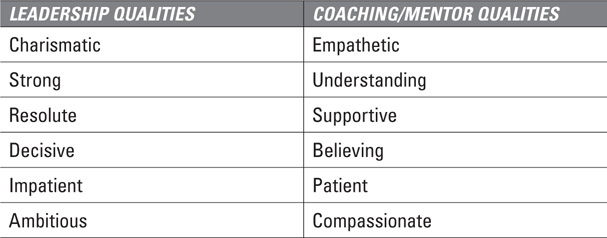

In my work with sales leaders, there is universal agreement that coaching is important and should be done more often. Many, however, don’t fully appreciate how different the qualities needed to coach effectively are from simply leading. Who are the leaders you most admire? Who were your favorite coaches? Think for a moment about the qualities those leaders possessed, versus those of the mentors or coaches you have had in your life. Which of the following did you include? (See Figure 18.2.)

FIGURE 18.2 Leader vs. Coach Qualities

Quite a gap, huh?

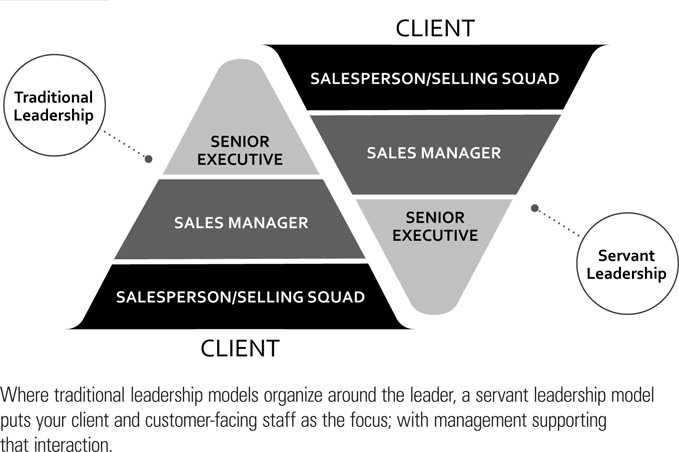

Coaching, in my view, falls under the heading of servant leadership. Since the 1970s, the topic of servant leadership has largely been ascribed to management thinker Robert Greenleaf. (Greenleaf, 1977) The concept has ancient roots and involves a leader’s belief in his or her mission and people, over oneself and one’s own ambitions. In the case of sales leadership, it involves turning the organization chart upside-down, so that the client supersedes all—the sales organization seeks to serve the client, and the leader serves the client indirectly through his or her work supporting the sales team.

SERVANT LEADERSHIP AND COACHING

An effective leader who is also an effective coach is aware of those moments when you are performing one role versus the other. (See Figure 8.3.) The levers you learn to pull in order to downshift into coaching mode are patience and restraint, regardless of whether your direct reports are salespeople who lead selling squads, or sales managers who manage a team of salespeople who at times create selling squads. You may find this difficult at first, but it takes a good process and practice to do effectively—remember, your sense of urgency and action orientation are prized as a leader. Patience and restraint may not be qualities that your manager was seeking when he or she first hired you as a sales leader; in fact, he or she may have been looking for the opposite. Possessing a willingness to jump in quickly and knowing when to do so can be invaluable when, for example, you’re setting strategy for a struggling business unit and when providing leadership to a team going through industry or organizational change. When coaching sales teams, however, you need to be able to find and draw on both of these qualities: patience, to provide space for the salesperson or selling squad to self-discover the issues, causes, and solutions; and restraint, to hold yourself back from putting on your super sales manager cape and solving the problem and therefore missing the opportunity to build the salesperson’s independence and investment in change.

FIGURE 18.3 Traditional vs. Servant Leadership

DEVELOPMENTAL SALES COACHING

How do you share developmental coaching feedback? Recall that we talked in Chapter 8 about the importance of giving and receiving balanced, specific, and honest feedback and in Chapter 9 about how to share peer-to-peer feedback in a selling squad’s Practice session.

Developmental coaching is typically done between a manager and a direct report. For example, this could include these scenarios:

![]() A sales manager coaching a salesperson on how to grow stronger as a selling squad leader

A sales manager coaching a salesperson on how to grow stronger as a selling squad leader

![]() A manager of a product area coaching a subject matter expert (SME) on how to elevate his or her contributions to a selling squad meetings

A manager of a product area coaching a subject matter expert (SME) on how to elevate his or her contributions to a selling squad meetings

![]() A senior executive coaching a line of business leader on how to create more collaboration across business lines

A senior executive coaching a line of business leader on how to create more collaboration across business lines

Developmental coaching tends to be longer term in nature than the type of peer-to-peer feedback that is limited to one’s contributions to a specific pitch, for example. This type of coaching focuses on one developmental area at a time—such as, how to conduct more effective Organize meetings—to foster incremental and sustainable change that may take several coaching sessions. And developmental coaching is best managed between trusted parties.

Good coaches are also willing to receive feedback on their coaching. Be willing to empower your direct reports with the same process and guidelines. Who knows? The master may become the student and vice versa.

Without a process, you may find that as a manager you stumble your way through coaching conversations. Servant leaders find their way to a process that works but, speaking from my own journey as a manager, trial and error can be painful for all involved and take time that you don’t have. You may be the kind of leader who is quick to ditch coaching until you are shown a process that works, get the space and support to practice it, and are asked regularly by your own manager for evidence and examples of your coaching experiences and results (as discussed above in the first of the three C’s: communication). Moving to a more team-based selling process is an example of behavior change that may be significant for many in your organization. As mentioned, behavior change can feel scary and risky, especially when it affects compensation, promotion, and even employment decisions. Engaged coaching is the medium to help people feel confident enough to bridge that gap.

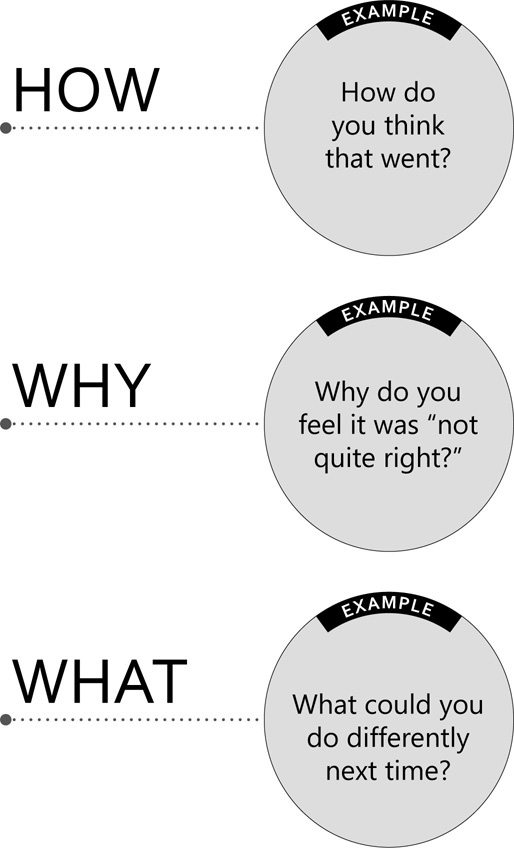

THE HOW, WHY, AND WHAT OF DEVELOPMENTAL COACHING

The words how, why, and what—in that order—are far more powerful tools in coaching sales teams than are speed, power, and leaping ability. (See Figure 18.4.)

FIGURE 18.4 Feedback Dialogue

Let’s look at how each of these three words prompts an important question in an effective sales coaching dialogue with one of your managers, selling squad leaders, or contributors:

![]() How: How did your selling squad perform during the sales call? How are your selling squad leaders progressing in their ability to create winning selling squads? How do you see the trends changing in your division’s win rates on the larger, more complex deals that require multiple selling partners? The how question leads, or forces in some cases, self-reflection by the manager, salesperson, or contributor. For you as a coach, it provides a view into your colleague’s level of awareness.

How: How did your selling squad perform during the sales call? How are your selling squad leaders progressing in their ability to create winning selling squads? How do you see the trends changing in your division’s win rates on the larger, more complex deals that require multiple selling partners? The how question leads, or forces in some cases, self-reflection by the manager, salesperson, or contributor. For you as a coach, it provides a view into your colleague’s level of awareness.

![]() Why: Why do you feel progress has been slow? Why was the team able to create that result? Why are we not seeing even stronger win rates? The why question allows you to guide the manager, salesperson, or contributor to identify the trigger that is causing the current state. As with your how question, asking a why question —rather than telling—provokes self-discovery and makes your colleague accountable for discovery.

Why: Why do you feel progress has been slow? Why was the team able to create that result? Why are we not seeing even stronger win rates? The why question allows you to guide the manager, salesperson, or contributor to identify the trigger that is causing the current state. As with your how question, asking a why question —rather than telling—provokes self-discovery and makes your colleague accountable for discovery.

![]() What: What are some ideas you could try to generate progress? What could you do to replicate this team’s success? What actions could you take to escalate your group’s win rate? The what question puts the manager, salesperson, or team in the driver’s seat with regard to their own development. And working with the ideas they generate increases ownership and commitment to follow-through. You’re able to monitor and watch—as servant leaders do—how the plan plays out, and are able to move on to other things.

What: What are some ideas you could try to generate progress? What could you do to replicate this team’s success? What actions could you take to escalate your group’s win rate? The what question puts the manager, salesperson, or team in the driver’s seat with regard to their own development. And working with the ideas they generate increases ownership and commitment to follow-through. You’re able to monitor and watch—as servant leaders do—how the plan plays out, and are able to move on to other things.

Your how, why, and what questions initiate and guide dialogue. As a coach, your next-level managers, salespeople, or contributors will expect you to have a view as well, so you should come prepared with that. The important point here is that each question kicks off that part of the conversation. It allows the salesperson or team the space for self-discovery of the issues, drivers, and potential solutions—prior to your sharing your views on the how, why, and what of the situation.

BEST PRACTICES IN DEVELOPMENTAL SALES COACHING

Even the most super of super sales managers among us have been able to find within themselves patience and restraint, and to use the above questions, employing the following eight simple tips:

1. Set a clear objective for each sales coaching session, focusing on outcomes that will gain the change you need to accomplish your goals.

2. Prepare for sales coaching sessions, especially those how, why. and what questions that will guide the person you’re coaching through a self-discovery process.

3. Provide a safe and supportive environment, encouraging honesty and reflection without judging, criticizing, or looking for “right” answers.

4. Listen more, talk less. One of the senior executives I coach writes two simple words on his notepad as a sales coaching reminder: “Shut up!”

5. Be more curious about each of your direct reports, and have the courage to ask “Why?” in response to their comments. Be willing to ask two to three questions before providing your views. You know from your own experience: people learn best from themselves.

6. Acknowledge that moving even an accomplished person out of a comfortable performance pattern will be, by definition, uncomfortable. Expect him or her to struggle, using silence when needed and providing support when appropriate.

7. See how developmental coaching benefits your team; including greater empowerment, independence, excitement, and vision to get to a higher performance level.

8. Realize what you gain by coaching your team; including increased skill level and performance from your team as well as more time for you to focus on higher value activities.

Coaching sales managers, selling squad leaders, and contributors is one of your key performance drivers as a manager. Leveraging it requires a process and some qualities you may not have needed to succeed in the past. So the next time you hear the cry for help from somewhere in Metropolis, hold off putting on the red cape and remind yourself that the ordinary sales citizen may just be smart enough to save himself or herself. In the process this will free up your time to tackle more important issues facing the great city.

WHO SHOULD BE COACHED?

Who in your organization needs coaching? Once you become accustomed to downshifting to coaching, and know how to do it, it’s like having a true superpower that you want to use wherever possible because you know that—other than hire-fire decisions —it drives the most significant impact in results. On one level, the question of who to coach is easy. Of your direct reports, you coach those who want to be coached. As it relates to selling squads, team leaders tend to need it the most. Because with every new opportunity and pivotal meeting, there may be a different team that needs to be created and organized. But who should coach members of the selling squad that, because of their role or product area, fall outside the scope of your management? The most effective selling organizations with which I work create vibrant feedback cultures, where people are used to skillfully exchanging feedback with one another—whether their selling partner resides above, below, or to the side of them on an organization chart. People who participate on sales calls, leader or contributor, should be coached regularly to refine and improve their impact in team sales meetings.

DEAL COACHING VS. DEVELOPMENTAL COACHING

Another form of coaching is deal coaching. Someone outside the core team is recruited as a coach to guide the team on a winning path. An organization that promotes collaboration encourages selling squads to use a coach to provide a feedback loop, allowing the team to course correct as its work proceeds. A selling squad’s coach can be internal or external, as discussed in Chapter 7.

WHEN SHOULD YOU COACH A SELLING SQUAD?

In this book, you have learned the process for building a winning selling squad—Create, Organize, Practice, Execute, Re-group. If you are a selling squad’s designated coach, your role is to coach to gaps in the team’s use of that process. There is an important role for you to play before and after that important client meeting. Consider participating in the team’s Organize, Practice, and Re-group meetings. The coach should be serving the core team as it prepares as a unit. This can include providing feedback on their work on knowledge leveling; the state of their planning for materials and logistics; and for each team member given his or her performance during team Practice sessions.

According to Hackman, there are three types of coaching “interventions” that can impact team effectiveness: the energy team members are contributing to the collective effort, the strategy they are using to carry out their work, and the knowledge and skill they bring to the party. (Hackman, 2002, p. 167) In terms of how as a leader you coach selling squads, it’s valuable to keep in mind two other concepts. First, you may recall Heidi Gardner’s research with professional services firms from earlier in this book, and her findings that it’s important to draw out and give weight to client knowledge, even when that knowledge is held by members of the selling squad who may hold junior roles in your firm relative to others on that team. (Gardner, 2012) Second, you may recall from earlier in the book my references to the work of MIT’s Sandy Pentland in the arena of social physics. (Pentland, 2012) That notion of equal talk time can help you as a selling squad coach ensure that the team’s decisions are based on all, not just the loudest, voices at the table. A coach can help guard against dominating influences in the group and solve for the free rider problem to ensure that the best ideas get surfaced by the people who are in the best position to know. This also helps make sure that the team is receiving equal contributions among its members and still factoring in external information.

Psychologist Ivan Steiner talks about “synergistic process gains and losses,” where the collective produces up to or below its potential. (Steiner, 1972) Hackman posits that coaches should seek to coach around these process gains and losses, and that there are three times when teams seem to be most receptive to coaching interventions: at the start, in the middle of the team’s collective work, and at the end of their work. (Hackman, 2002, p. 179) This confirms our earlier discussions on the importance of a selling squad’s feedback loop, and clarifies the pivotal role an effective coach can play.

SELLING SQUAD COACHING INTERVENTIONS

Let’s take another look at what a coach can do at each stage:

![]() During an Organize meeting or call, a coach can—directly with a selling squad or by supporting its leader—ensure the team is aimed properly at the start, and help the team refine preliminary ideas and scan for new information that may have become available since the selling squad’s work together began.

During an Organize meeting or call, a coach can—directly with a selling squad or by supporting its leader—ensure the team is aimed properly at the start, and help the team refine preliminary ideas and scan for new information that may have become available since the selling squad’s work together began.

![]() During a Practice session—ideally scheduled far enough in advance of a pitch or meeting—the coach can facilitate the incorporation of feedback and new information in the selling squad’s final work.

During a Practice session—ideally scheduled far enough in advance of a pitch or meeting—the coach can facilitate the incorporation of feedback and new information in the selling squad’s final work.

![]() During a Re-group meeting, the coach might enable the team—before it disbands—to learn from their work together so that the selling squad and its members grow more effective in future outings.

During a Re-group meeting, the coach might enable the team—before it disbands—to learn from their work together so that the selling squad and its members grow more effective in future outings.

Being an effective selling squad coach requires trust and credibility with team members. We talked earlier about the importance, qualities, and process for delivering peer-to-peer feedback effectively. That same concept of delivering balanced, specific, and honest feedback while leveraging the how, why, and what questions mentioned earlier, will enable you as a selling squad’s coach to effect a coaching intervention for the team, its leader, or team members in a way that allows them to maximize their impact on a high-stakes meeting and to grow professionally. When handled poorly, not only can a coaching intervention throw a team off-course, it can also destroy trust and damage relationships. This is especially important to note if you as a manager seek to coach people in your reporting structure.

WHERE SHOULD COACHING OCCUR?

Choosing an appropriate location for coaching is worth touching upon. Intact teams whose members trust one another enough to allow feedback to be given and received collectively are rare. Short of that, team feedback should not be given to the team as a collective. Individual feedback on member contributions is best given one-on-one, in a private setting to ensure attention and receptivity. Team feedback should also be delivered in a setting that minimizes onlookers and keeps everyone open and focused. When time is short, selling squads have a habit of giving feedback as a collective. It is important to note that while this process is expedient and usually feels good to the team leader, it is not the most effective way to produce behavior change among team members. Those who are struggling, and who may be outside their comfort zone already, may feel overwhelmed and this may further increase their sense of pressure. The result may be an even weaker performance during the client meeting than what would have been possible had they been coached in a safe setting.

WHO SHOULD COACH?

If your organizational climate facilitates strong collaboration, you and your fellow leaders and managers ought to be able to discuss and decide amongst yourselves, resolve any conflicts, and reach agreement on who coaches which selling squads, modeling the behaviors you seek on your own individual teams.

Hackman’s view is “what is critical is that competent coaching is available to a team, regardless of who provides it or what formal position those providers hold.” (Hackman, 2002, p. 194)

Selling squads have options in choosing a coach for their team. The team might have access to an internal coach who is a manager, designated sales coach, or salesperson outside the core and extended teams, or an external sales coach.

Internal or external, “competent” coaching means credibility. If you seek to coach a selling squad effectively, you should bring to your work with a selling squad the following six qualities:

1. You should have or be able to establish a trusting and trusted relationship with each member of the team.

2. You should be able to coach skillfully, bringing the qualities mentioned earlier including being supportive, patient, and discreet.

3. You should be experienced—to understand the domain in which the selling squad operates and to appreciate what an effective team sales meeting looks like.

4. You should be skillful and use an effective coaching process, akin to the one described above, that allows the team members to, first, learn from themselves and each other and, then, from you as an engaged and insightful observer. Facilitating an internal feedback loop—with a team or one-on-one—enables the selling squad and its members to better meet their performance goal while growing professionally in the process.

5. You must be available. A great coach who is credible but too busy to engage as and when needed by the team in the lead-up to a critical sales meeting offers little value.

6. You must be objective. Because you reside outside the core and extended teams, you are able to deliver feedback that is unbiased and avoids a group’s tendencies to fall in love with its own ideas.

Compensation

The final of the three C’s is compensation. Even if you are not a compensation expert, you will probably recognize the truth behind the following two statements:

1. Not changing your compensation plan is unlikely to fully change behaviors.

2. Changing your compensation plan on its own is unlikely to fully change behaviors.

As it relates to compensation, an old manager of mine was fond of the saying, “You don’t play games with people’s comp.” What’s true about this statement is that money is a very personal topic. And changing how it’s delivered can impact a person’s current obligations and future plans. For many it also sends a message, intended or not, about their worth to you and your organization.

Those are not reasons to leave a compensation program in place that has fallen out of step with the realities of your business plan today and going forward. Choosing to not adjust the plan but expecting different behaviors is, well, wishful thinking. According to ZS Associates, “sales force incentives play a big role in reinforcing what’s important.” (Moorman & Albrecht, 2008, p. 33) It’s hard to ignore the power of a leadership team that, as described above, is unified, relevant, specific, and engaged in its messaging about why behavior change is needed and what is expected; and supporting it with coaching. It’s easy to see how a compensation plan that continues to reward individual performance focused on one’s own silo might send an even more important message that people should carry on with their current behaviors.

On the other hand, changing a compensation plan alone to reward better teamwork in sales and customer meetings is equally unlikely to change behaviors. Picture this: a sales manager has violated the “don’t play games with people’s comp” rule and, through the changes, has sent some type of message about more collaboration, cross-selling, and team-based selling. Yet individual performers have succeeded based on the old rules, and they’re all of a sudden being asked to change. They are not being told why change is needed, what they personally need to change in order to be effective, or how to accomplish it. In addition, the manager and his fellow leaders are changing none of their own behaviors in working together. The sales manager is neither addressing the risks his people feel about changing nor helping them, through engaged coaching, as they try to adapt to this new compensation plan.

You can see how these mismatches are likely to create all sorts of random results, including people gaming the system without any changes to their go-to-market behaviors, groups of people mangling the process of trying to work together, and solid individual performers deciding to jump ship after concluding that they are no longer wanted in this system.

Consultants Michael Moorman and Chad Albrecht from ZS Associates suggest the following best practices on sales incentive plans to facilitate better team selling across the organization:

![]() Sales force structure: This involves defining or redefining roles so that people can better understand what actions fall at their feet versus those of their colleagues. This might include appointing someone as a key account manager who helps the team organize its activities, including cross-selling and looking for broader opportunities that cross the different product areas in which individual team members are focused.

Sales force structure: This involves defining or redefining roles so that people can better understand what actions fall at their feet versus those of their colleagues. This might include appointing someone as a key account manager who helps the team organize its activities, including cross-selling and looking for broader opportunities that cross the different product areas in which individual team members are focused.

![]() Sales process: Helping people see the stages of a sale, and even the parts of a client-focused meeting or call, is foundational to facilitating better collaboration. For some in your organization, this type of investment may seem like it’s not needed since this is how they sell today. For others, it’s urgent as the gaps have grown large between their product-pushing style and the way customers buy today and how other parts of your organization go to market. Despite the groaning, everyone will appreciate a unified process they can collaborate around for more effective sales meetings that produce more, different, and better opportunities.

Sales process: Helping people see the stages of a sale, and even the parts of a client-focused meeting or call, is foundational to facilitating better collaboration. For some in your organization, this type of investment may seem like it’s not needed since this is how they sell today. For others, it’s urgent as the gaps have grown large between their product-pushing style and the way customers buy today and how other parts of your organization go to market. Despite the groaning, everyone will appreciate a unified process they can collaborate around for more effective sales meetings that produce more, different, and better opportunities.

![]() Sales force deployment: How well organized are resources in the field to allow for collaboration versus competition? Thought should be given to how people will cover a territory—whether that’s defined by geography, channels, and/or accounts. Free-for-alls can be interesting to watch if you’re not part of them. Define the ground rules for how teams will operate within that territory. Examples of this include key account team and “mirroring,” which means representatives from different lines of business jointly own a territory.

Sales force deployment: How well organized are resources in the field to allow for collaboration versus competition? Thought should be given to how people will cover a territory—whether that’s defined by geography, channels, and/or accounts. Free-for-alls can be interesting to watch if you’re not part of them. Define the ground rules for how teams will operate within that territory. Examples of this include key account team and “mirroring,” which means representatives from different lines of business jointly own a territory.

![]() Incentives: ZS Associates shares the following best practices in aligning the compensation program with the above best practices to produce better collaboration in finding, developing, and managing accounts and opportunities:

Incentives: ZS Associates shares the following best practices in aligning the compensation program with the above best practices to produce better collaboration in finding, developing, and managing accounts and opportunities:

1. Make the plan simple to understand.

2. Keep the group of metrics small (three priorities or fewer).

3. Make the measures felt at the individual level. Setting a metric too broadly, say at the regional level, can be easy to administer but may feel too distant for any person within that region to impact. Structure incentives to pay out to the team’s members when they achieve a performance goal set for a dedicated or “mirrored” account team. For organizations that are unable to structure teams in dedicated or mirrored territories, getting incentives right is trickier. Balancing levels of contribution to, and payment for, that success is tough to administer and can cause disagreements about who contributed how much to which sale.

4. Be sure that incentives line up with (1) overall compensation packages that remain competitive for specific markets and roles and (2) line of business goals so that associated members continue to stay focused on that line of business rather than promoting other product areas that may produce better incentives.

5. Align sales incentives with those of senior management to avoid conflicts between leadership and salesforce behaviors. (Moorman & Albrecht, 2002)

Communication, coaching, and compensation. These three C’s allow you as a leader to set the organizational climate within which effective selling teamwork happens within your span of control.

Tips for Selling Squad Leaders and Members

The organizational setting in which groups are formed—for selling and other work tasks—play a big role in creating the conditions that allow your selling squads to come together as high-performing teams. The company you represent exists in its current state; change, as described here, requires leadership teamwork, time, shared commitment, and energy. As a passionate client advocate, you realize that there must be actions you can take today with your colleagues that will produce better outcomes in this new selling environment, and within your organization to influence change that will lead to better conditions for teamwork across disciplines.

Let’s look first at things you can own today that will produce better outcomes in your selling squad meetings.

Build Your Network

Many professional services firms, for example, have grown in their appreciation for how important internal relationships are in producing better client outcomes. They encourage and provide forums for networking. The more consultants within a firm know one another, the more effective they can be in building engagement teams well suited for client needs and identifying opportunities to serve clients outside their own discipline. Even in such firms, many consultants focus only on the work, rather than both the work and the relationships that will allow them to find and deliver that work. You don’t have to work for a consulting firm to begin adopting this best practice.

What if you work for an organization that neither encourages nor facilitates internal networking? Uh, you’re a sales or client-facing professional, you make your living figuring whom you need to connect with at client organizations and then getting after it. Building your internal network takes the same sort of discipline. As with prospecting, this is not networking for networking sake; it has intention. How well do you know your organization’s capabilities? Who are those people connected to far-flung capabilities that would help you to better understand what customer demand that capability is tapping into? Knowing those people will allow you to bring a broader scope to client meetings. And, when appropriate, these same people may be instrumental in developing solutions to client needs that cross your organization’s product siloes. They can also become a part of a selling squad that prepares and practices with you as a cohesive team in making a compelling and winning case to a client. None of these things can happen without a broad network within your organization.

Invest in Your Internal Relationships

We touched on this subject in Chapter 5 when we discussed the importance of developing mutual trust and credibility as a foundation for strong selling partner relationships. Consider the time, thought, and energy you invest in cultivating external relationships. You initiate contact, you stay in touch, you prepare, you seek to understand them better professionally and personally, you help them accomplish their goals so that you can reach yours, you follow up diligently. How does that compare with the way in which you manage your internal relationships?

Most sales professionals, when asked, admit there is a large gap between the two. And it is easy to see why. On its surface, you as a client-facing professional are deployed and compensated to go out and gain distribution for the products and services that your company offers. Your sales manager encourages you to build external relationships since, as many sales managers are fond of saying: “You don’t meet your next million-dollar prospect in your office or living room.” Your manager may even try to promote more calling activity by including in your goals specific metrics for prospect, customer, and center of influence (referral source) meetings or calls. So it can feel as if time spent with internal colleagues is unproductive and takes you away from meeting your sales goals.

One successful salesperson I coached told me a story about a company she worked for. Leadership prohibited her from being in the office between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. and installed a GPS tracking device on her car so they could see her whereabouts whenever they desired. When she visited another office belonging to that company or its affiliates, she was instructed to “stop wasting her time.” It’s hard, even for a thick-skinned salesperson, to not get frustrated by contrasting messages of sell more and sell bigger with sell solo.

At one extreme, consider first that if you are out of the office all day, every day, you will likely exceed your activity metrics for sales calls. Where you may falter, however, is cross-selling other parts of the company and finding larger enterprise sales.

At the other extreme, let’s say you’re a salesperson who has a great internal network, and knows everyone in the company. You are considered a great team player and are given high marks for referrals you make to other parts of the company. However, perhaps your pipeline is relatively empty, your win rate is low, and your calling activity is far below the activity metrics set for your position.

How do you find the optimal point between those two extremes and enable yourself to keep your internal relationships and knowledge current, while executing a sales calling plan that connects this network into the best external opportunities? There is certainly a lot of room between these extremes. Taking into account how the market has changed, and even how your own organization has evolved over time, is it possible to update your view of a “day in the life of” a salesperson? That by not just knowing the names of the salespeople in other parts of your company, you knew them. Took the time to really connect with them. Grabbed lunch or dinner and, as you would with a prospect or referral source, prepared for that time, came to understand their ambitions and challenges, the things that matter most to them personally. Understood where your interests were aligned, how you could help one another find prospects, how you might be able to collaborate on the same opportunities to create broader solutions, how you could work together on team pitches, or just stay in touch.

Address Conflicts

It’s easy to avoid conflict as a salesperson in a large organization. There are a limitless number of workarounds, including working with colleagues you find to be more receptive. Effective teams are able to work through conflicts and disagreements. As you build your network and invest in your internal relationships, what are the odds that between engaged, candid colleagues there will only be moments filled with rainbows and puppy dogs?

Forging larger relationships that span siloes works in many ways against the daily momentum within your own organization. It also means creating solutions that don’t yet exist as an off-the-shelf capability. That friction can create conflict among colleagues. You may even discover that in working with a colleague from another group for the first time his or her ideas for meeting preparation differ markedly from your own. As a sales and client professional, you resolve objections from clients, prospects, and centers of influence every day. How come it’s so easy to get frustrated with our internal colleagues when they don’t immediately snap to attention and do what we think they should do? What if we showed the same patience we do with external parties when we are able to resolve their concerns effectively? Instead of ignoring the conflict, what if we acknowledged it, and sought to understand it better before trying to find a way to resolve it? When channel partners are able to know, trust, and work through issues together, imagine how clients view those relationships as they are sizing you up across the table and considering whether to place significant work that involves cross-organization collaboration to deliver it.

Invest in Process

This book is all about going to market as a team, using a team sellingprocess. Now sales process can differ across disciplines within the same firm. Where one discipline has spent the time to carve out and define a sales process, one uses a different process, and another one uses no process at all. Effective business development professionals use a process—both in shepherding an opportunity over the course of its life, and in managing client touchpoints. It can be frustrating when colleagues with whom they need to work use a different or no process at all.

Teams win together, and teams lose together. Processes that are built on best practices, and applied skillfully and cohesively by a team, will produce consistent results. Random processes or routines produce random outcomes. The team must rally behind a process to win. So how will you close those gaps so the team can be both effective and efficient in its work? We talked earlier about how winning teams work together to resolve conflict; this may be one of those cases. Though we may describe the process around a client meeting in different words, it’s tough to imagine anyone disagreeing that this process should include at a high level: time to prepare and practice before the meeting; during the meeting, time allocated to start, discover, present, and end the meeting; and afterward, time to debrief. Establishing expectations at the start sets for members of your selling squad a clear picture of their roles before, during, and after the sales meeting. It allows everyone to visualize, in their own unique way, what that journey looks like.

Create a Feedback Loop

As selling squads come together for important client meetings, the cohesion that is created can form an insular circle that prevents teams from making adjustments needed to win. As an external sales coach, I see—sometimes even within the same organization—widely different examples of feedback cultures. In some groups, feedback comes at you from every angle all the time. In others, it’s the Sahara Desert of feedback.

So how do you bridge those gaps to create a feedback exchange with colleagues and business units that you work with today, and those with whom you would like to work in the future? You already understand the importance of keeping your network current and investing in those relationships. You also recognize the importance of working effectively with these colleagues as you team up on selling squads before, during, and after an important client meeting. Effective teamwork includes communicating with one another to help each other maximize your contributions to the team and your impact in the customer meeting.

We have talked about the importance of feedback among selling partners around the selling squad Build Process. We discussed how “P-ER” can be used to develop stronger partnerships through: pre-invest (before the Build Process begins); engage (during the five stages of the Build Process); and re-invest (after the Build Process for a client meeting or pitch is complete. As the team leader in recruiting team members, remember to ask people about their views on and comfort level with feedback. As the group begins to form, set expectations, and gain agreement about when and how feedback will be given, so your colleagues know it will be real feedback, rather than criticism labeled as “feedback.” Linking it to the group’s performance goal—say, winning a new account that will allow the firm to begin penetrating a high-growth market—makes it feel less personal, and more about a mutual exchange of information intended to allow us to work together more effectively and to win. And a nice by-product of this feedback is that it allows team members to grow individually, and your team, if it works together again, to grow even more effective in future meetings.

Now, let’s say you have taken ownership where you are able to. Yet, the organizational climate in which you operate is not conducive to cross-silo teamwork. What actions can you take?

When Your Organization Lacks a Feedback Culture

SEEK COACHING