CHAPTER 17

CONCLUSIONS: MANAGING SERVICE AND RELATIONSHIPS

“Good intellectual analysis and thorough planning of a service-oriented business is valueless unless management has the determination, courage and strength needed to implement their visions and plans.”

INTRODUCTION

This final chapter will summarize the essence of service management and service strategy. First, implications for management of the Service Profit Logic are presented. Then, the scope of service management and marketing is summarized. Thereafter, consequences for marketing of the service and relationship approach are discussed, followed by seven ‘rules’ of service. Finally, barriers to achieving results in an organization are presented.

A SUMMARY OF MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS OF THE SERVICE PROFIT LOGIC

From a commercial point of view, adopting a service logic and applying service management principles in business requires a clear understanding of the Service Profit Logic and its implications for management. As we have demonstrated throughout this book, in a service organization the economic result is generated in a dramatically different way as compared to conventional product manufacturing. Therefore, the Service Profit Logic requires equally dramatic rethinking about several management issues. This rethinking, pointed out and discussed in the previous chapters, is summarized in Table 17.1.

Managerial implications of the Service Profit Logic.

Marketing management |

Holistic customer management through Promise Management instead of functionalistic marketing management. |

Human resource management |

Externally-oriented Internal Marketing instead of internally-oriented HRM only. |

Quality management |

Management of Customer Perceived Quality instead of internally-oriented quality assurance and management only. |

Productivity management |

Holistic externally-oriented management of profit effectiveness instead of internally-oriented cost efficiency management only. |

Operations management |

Customer-focused management of operations; management of service production processes as well as of systems and resources used, including customers. |

AN OVERVIEW OF A CUSTOMER…FOCUSED SERVICE STRATEGY

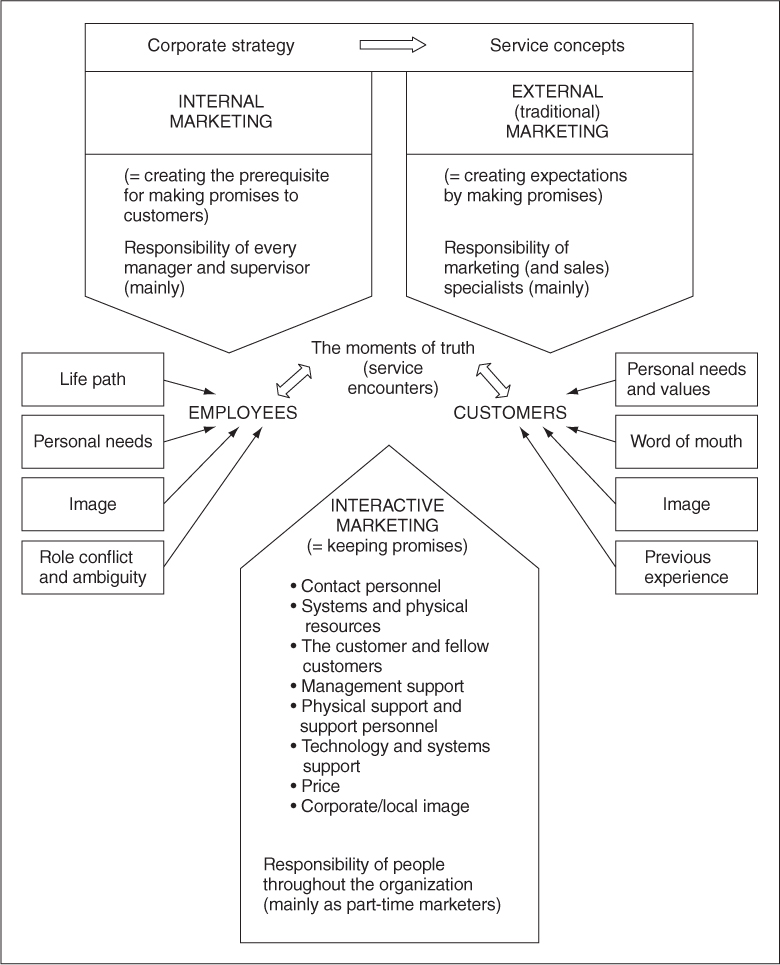

In Figure 17.1 the essence of service management and marketing is summarized. The core of the process is the series of moments of truth of service encounters, where the employee and the customer, supported by systems and technology and physical resources, meet and interact. Employee–customer interactions are not always the normal form of interaction. In many cases the customer interacts with IT and other systems, infrastructures or fellow customers and only on certain occasions, such as when a failure has occurred or the customer needs advice, interactions with contact employees take place. These service encounters influence customers’ value-creation. If they are not well taken care of, the perceived service quality (service quality as perceived by the customer) is damaged, and the service provider may lose business. The main focus in service competition is the continuous management of the series of moments of truth in service processes, as well as adequate support from managers and supporting functions and from investments in technology, operations and administrative systems. If the ongoing moments of truth are well taken care of, the service encounters will turn out well, and the relationship will probably develop satisfactorily and lead to continuous business and loyal customers.

Value for customers is not, of course, entirely dependent on what takes place in service encounters. Much value support may have been pre-produced by the supporting part of the organization. The final value for the customers emerges in the consumption or usage of the service. From the customer’s point of view, however, what happens in the service encounter is always decisive. If the customer is not satisfied with what he experiences, then the pre-production efforts in back offices, or by manufacturers in factories, have been in vain.

FIGURE 17.1

An overview of a customer-focused strategy.

MAKING PROMISES: TRADITIONAL EXTERNAL MARKETING

Customers’ experiences of service encounters do not take place in a vacuum. They go into them with certain expectations, which are partly created by the service provider itself. By its external marketing process, involving traditional marketing efforts, such as market research, personal selling, advertising, Internet communication, direct mail, sales promotion and pricing, the organization makes promises that should correspond to the customers’ everyday activities and processes and their personal needs, values and wishes. The full-time marketers inside the organization or outside of it (for example, in advertising agencies and market research firms) are usually responsible for this type of traditional external marketing.

These promises are enhanced or counteracted in the minds of the customers by their previous experiences, if they have had any, by word-of-mouth communication, and by postings on various websites and discussion in various social media, and by customers’ conceptions of the image of the service provider.

ENABLING PROMISES: INTERNAL MARKETING

Employees’ abilities, skills and motivation to meet the expectations of customers are backed up by internal marketing efforts. By creating and maintaining a service culture, as well as by actively marketing the service perspective as well as new goods and services, systems and processes to the employees, and by making use of all available means of motivating the employees and enhancing their skills for service-oriented and customer-focused performance, the organization can prepare its employees for part-time marketing responsibilities. Thus, internal marketing is a must for creating the prerequisite conditions for keeping promises.

Internal marketing is a top management responsibility, but it is also the responsibility of every manager and supervisor. Of course, the personal needs of the employees and their perceived job satisfaction and supervisors’ encouragement, as well as their life path and their image of the employer, also have an impact on the employees’ performance as part-time marketers. Moreover, employees are influenced by role ambiguity, related to, for example, what they perceive customers and the organization expect them to do. Employees are also influenced by role conflicts, for example, when what management says the employees should consider important in their jobs conflicts with the opportunities to live up to these intentions that management provides in terms of skills, support and incentives, and with their personal beliefs and values. Grocery retailers sometimes make promises in their advertising about products and additional service, for example cooking advice, that customers can get in the store. If there are not products left on the shelves or if employees, a large proportion of whom may be working on a low-pay, part-time basis, do not have the cooking knowledge or interest needed to give such advice to customers, who may often be better cooks than they are, they will be put in an awkward situation which they cannot handle. If they get information from customers about what they are supposed to do, which is not uncommon, the situation is even more frustrating for the employees. Bad internal relationships and bad external relationships with customers follow from this.

Another aspect of how well promises are enabled is the support of systems and technology – information technology and other – on which the employees depend. If customer information is difficult to retrieve from databases, or if files are not properly updated, contact employees have difficulty in providing customers with attentive, prompt and accurate service. Moreover, a lack of systems support also has a counterproductive impact on internal marketing processes in the organization.

Empowering employees is another key aspect of enabling promises. Employees who have the authority to handle customer contact situations themselves, and who have the technical skills and the motivation to take this responsibility, will keep promises effectively and in a customer-oriented manner. Here again, a lack of systems support can seriously diminish the potential positive effects of empowerment. However, it must always be remembered that empowerment without enabling does not work and may even be counterproductive and discourage employees. Enabling means that empowered employees are supported by necessary supervisory and physical support, and have been provided a required level of knowledge and skills to handle customer contact situations.

KEEPING PROMISES: INTERACTIVE MARKETING

What actually happens in the moments of truth of the service encounters, where customers and employees meet and interact, determines whether customers’ experience meets their expectations. If experiences are equal to or higher than expectations, the perceived service quality is probably good; otherwise, there may be a quality problem. Good quality is a strong basis for a long-term customer relationship, including resales and cross-sales, as well as for favourable word of mouth and image.

Thus, keeping promises is one major aspect of the interactive marketing process. The customer contact employees are most often the key to success. However, information systems, operational systems and physical resources, and the customers, all influence interactive marketing performance. Although the role of the employees is most often paramount, other resources must not be neglected. First of all, there is a range of situations in which customers interact only with systems and physical resources. Using an ATM, making a local telephone call, sending a text message (SMS) from a mobile phone, playing digital games or making a purchase on the Internet are examples of such situations. Second, employees need a service-oriented operational system and proper computer technology, customer databases and other physical resources to be able to create positive moments of truth. However, one should never forget that if the technology or automatic service production system does not work, breaks down or cannot be operated, the key to recovering the situation is a service-minded and customer-focused employee. As has been discussed in previous chapters, if there is a problem of any sort, the service provider most often gets a second chance. However, in such service recovery situations the contact employees’ role and responsibility for success is paramount.

The physical support of support personnel and functions, as well as management support and leadership, are critical to the service orientation of the customer contact employees and systems of the visible part of the service process. Furthermore, customers’ experiences in service encounters are influenced by the corporate and/or local image of the service provider. Finally, the price level and possible price offerings have an impact on the level of customer satisfaction. This is not always altogether true, however. For example, if a manufacturer needs service and spare parts in order to keep its machines running, and if every hour of delay means thousands of euros, pounds or dollars of lost production and sales, he will probably be willing to pay almost anything to get the service.

Interactive marketing and keeping promises is almost entirely the responsibility of operations and other traditionally non-marketing functions. Therefore, employees involved in such functions are called part-time marketers, with dual responsibilities … for operations, or whatever their tasks concern, and for the marketing impact of their performance as well. To some extent, full-time marketers are also involved, but their role is marginal. Of course, in most business-to-business relationships the sales representatives have continuous responsibility for their customers. They cannot, however, do much to rescue a customer relationship if the organization has made a customer sufficiently dissatisfied with the service quality. In the short term the organization may be able to hold on to the customer’s business; in the long term it loses customers.

Keeping promises is also dependent on how productivity management is understood. If productivity is predominantly considered a cost efficiency management issue and not a profit management issue, where external effectiveness and internal efficiency considerations are integrated in decision-making, service quality is easily hurt and the interactive marketing performance deteriorates.

FROM TRANSACTIONS TO RELATIONSHIPS IN MARKETING

Service processes are inherently relational. Normally, interactions between the customer and the service provider occur and continue for some time. In many cases, service is consumed or used on a continuous basis. The same customer meets the same service provider over and over again. Service marketing has often been difficult and considered less effective because service firms have not recognized that service is inherently relational and have instead taken a transactional approach in their marketing strategies.

There are certainly situations where a transaction marketing approach leads to good results, and there are customers who do not appreciate relationships in commercial contexts, but as a principle, a relationship approach can be expected to lead to better results in service competition. Because markets are maturing and new customers are difficult to acquire, other than by poaching them from competitors, long-lasting relationships with existing customers become exceedingly important. It is much more difficult to compete with a core solution, whether it is a physical product or a service process, than before. Firms have to develop total service offerings to support competitive value for their customers. This means that more and more businesses have become service businesses and that service competition has taken over. Sometimes a transaction approach can work, but generally speaking these developments require a relationship approach to managing customers (and other stakeholders, such as wholesalers, retailers and other distributors).

CONSEQUENCES FOR MARKETING IN SERVICE COMPETITION

Because of the transaction marketing traditions, the marketing mindset and mainstream marketing concepts and models do not fit service competition very well. In this section consequences for marketing in service competition of its transaction-oriented traditions and the requirements of a service and relationship-focused perspective,1 respectively, are discussed. In Table 17.2 summarizes these consequences and requirements.

Diffusion of customer-focused activities (that is, the existence of marketing-like behaviour). Due to the transaction-oriented traditions of marketing, a customer focus normally exists only among full-time marketers and salespeople, who have been trained and appointed for marketing and sales tasks. When performing their jobs people outside these groups are generally not focused on customers. However, a service perspective demands that a customer focus is present throughout the firm. Wherever customer interfaces occur and customer contacts take place, a customer focus and marketing-like behaviour should exist. People who are engaged in such activities are part-time marketers. This goes for internal customers as much as for ultimate, external customers. All customer contacts have to be taken care of in a customer-focused or marketing-like manner, otherwise the total marketing process fails.

Dedication to customer management and a customer focus (that is, the existence of marketing attitudes in the firm). Normally, only a limited part of the organization, outside the group of full-time marketers and salespeople, takes a genuine interest in the firm’s customers. A firm that faces service competition and adopts a service perspective has to be customer-focused throughout the organization. Everyone who interacts with external or internal customers, including support persons whom customer contact persons are relying upon, have to be dedicated to a customer focus and have a marketing mindset. If they are not, the customer contacts will be taken care of in an inconsistent manner and customer perceived service quality will suffer, and in the end marketing will fail.

Consequences for marketing in service competition of its transaction-related traditions and of a service and relationship-focused perspective, respectively.

Aspect of marketing |

Consequences of transaction-related traditions |

Requirements of service and relationship-focused perspective |

Diffusion of customer-focused activities (marketing) |

A customer focus normally exists only in some of the places where customers interact with the firm. |

A customer focus has to be present throughout the organization, wherever external or internal customers are present. |

Dedication to customer management (marketing) |

Only a limited part of the organization is engaged in customer-focused behaviours and has a customer-focused attitude. |

In addition to full-time marketers and salespeople, a major part of the organization must be committed to customer-focused attitudes and behaviours. |

Organising for customer mangement (marketing) |

Marketing is normally a hostage of marketing and sales departments. Marketing is normally organized in marketing departments consisting of full-time marketers only. |

All marketing cannot be organized in a traditional sense. Only full-time marketing can be organized in a specialized department. In part-time marketers a customer-focused (marketing) attitude can only be instilled. |

Planning and preparing budgets for customer management (marketing) |

Plans and budgets for customer management (sales and marketing) are normally plans of sales and marketing departments only. |

Planning and preparing budgets for customer management must be part of all planning in a firm and co-ordinated in the business plan. |

Commitment to internal marketing |

All marketing and sales people are considered marketing professionals. Hence, no internal marketing is needed. |

Part-time marketers outnumber full-time marketers several times. Hence, internal marketing is of strategic importance. |

The term used for customer management (marketing) |

For a century marketing has been used as the term for customer management. |

Marketing as a term may relate too much to customer acquisition only. Moreover, part-time marketers often do not accept being involved in something called marketing. Hence, this term may be outdated and psychologically wrong and therefore not useful as an overall label for the process of acquiring, keeping and growing customers (customer management). |

Organising for customer management and customer-focused performance (that is, organizing marketing in a service business). In most firms marketing is the hostage of marketing departments. Firms have marketing departments staffed with full-time marketers who are highly visible in the organization and often run large external marketing campaigns. People outside the marketing department easily believe that the firm’s total impact on the customers, that is, total customer management, is taken care of by that department, and by sales departments. However, a service perspective requires that almost everyone as part-time marketers take responsibility for customers. Of course, not everyone can be placed in the marketing department and report to its director. It is impossible to organize marketing in a similar manner to its traditional arrangement in consumer goods marketing firms. Only the fulltime marketers, the specialists on customers, can be organized in one department totally dedicated to marketing and customer-focused behaviour. Everyone else, the customer contact employees and support employees as part-time marketers, whose main job after all is to produce a service or take care of some administrative tasks, albeit in a marketing-like fashion, belongs to their own department or processes. However, in spite of this, they have dual responsibilities. A marketing attitude of mind has to be instilled in them so that when doing their main jobs, they have the skills and motivation needed to perform them in a customer-focused manner. Hence, marketing can only partly be organized. Mostly it is instilled in the organization as an attitude of mind.

Planning and preparing budgets for customer management and customer-focused performance (that is, preparing marketing plans and budgets). Normally, what are called marketing plans and marketing budgets are prepared within the marketing department and mostly only cover activities planned and implemented by that department. Then the marketing plan becomes a plan for traditional external marketing only and the budget prepared for marketing becomes a budget for external marketing. In the plans governing other customer-contact activities performed in other departments and processes, that is, in plans governing the remaining parts of customer management, a customer focus is normally marginal or even lacking. Everyone knows that activities that have an impact on the firm’s customers are planned in the marketing department and budgets for such activities are prepared there. Therefore, marketing plans and budgets truly become hostages of the marketing department. In a firm that adopts a service perspective, a customer focus has to be present in all plans developed in the organization and in all budgets. Hence, the plan and budget prepared by the marketing department is only a minor part of the total customer management (that is, total marketing) planning and budgeting in the firm. Ultimately, all these sub-plans have to be co-ordinated, and probably this can best be done in the firm’s business plan.

Commitment to internal marketing. By definition, full-time marketers and salespeople are, or should be, customer-focused. They are also trained and motivated for marketing-like performance. Traditionally, no additional marketing-focused training for other people in the firm is considered necessary. However, when adopting a service perspective the firm has part-time marketers throughout the organization in a number of different organizational units and processes, who from the outset are not appointed for customer-focused behaviour and whose basic training is not related to handling customer contacts in a marketing-like fashion. Neither can they be expected to have a customer-focused attitude. However, they have customer contacts on a regular basis and they outnumber the full-time marketers several times. Hence, internal marketing is not only a tactical issue, it is of strategic importance to the firm. If internal marketing is lacking or less effectively managed and implemented, customer contacts will be handled badly, perceived service quality will suffer and the total marketing process fails.

The use of the term ‘marketing’ for customer management. Customer management, that is, being focused on customers and taking care of customers, is as old as the history of trade and commerce. The term marketing has been used for this process for roughly 100 years. Hence, it is a very new term. On no tablets of stone is it written that marketing, under all circumstances, is the best label to use. Indeed, marketing may turn out to be a problematic term in firms adopting a service and relationship approach, where the commitment to customers is required of a host of part-time marketers in almost every corner of an organization. First of all, this label has developed as a term describing the act of acquiring customers, persuading customers to buy and creating sales. It is an inside-out label. The very word ‘marketing’ refers to a movement, moving out onto the market. Today in service competition, when forming and maintaining longer-term relationships are a major part of customer management, customer acquisition and persuading customers to buy are still important tasks, of course, but so much else related to keeping and growing customers and creating a sense of connectedness with customers (and other stakeholders) is also important, and perhaps an even more important part of the customer management process. Hence, the term marketing refers only to a part of what ‘marketing’ is today, and perhaps often to the less important part.

Secondly, in the minds of people with part-time marketing responsibilities, marketing as a term is frequently loaded with negative associations. According to them, marketing is far too often equal to persuasion, pushing and making people buy things they do not need. And who would like to be part of that? So, for potential part-time marketers the very term ‘marketing’ easily creates resistance to adopting a customer focus. They simply do not listen to internal efforts aimed at explaining why they, as part-time marketers, are part of the firm’s total marketing process. Therefore, for a firm in service competition to become truly customer-focused it may even be necessary to abolish the label ‘marketing’ for customer management. Psychologically this label is wrong and may become a hindrance for change processes, and it does not refer to the whole customer management process of acquiring, keeping and growing customers, where the latter two aspects are frequently more important than the first one (to which the term marketing originally referred).2

Throughout this book the term ‘marketing’ has been used for customer management. As a more appropriate term that would be even to some limited extent agreed upon or understood in a more or less similar way does not seem to exist, for the time being we have chosen to label the customer management process ‘marketing’.3 However, we suggest that firms seriously consider taking another, more appropriate and psychologically less problematic label for the customer management process in use.4 Of course, this also goes for the label ‘internal marketing’.

GUIDELINES FOR MANAGING SERVICE COMPETITION

In this last section of this concluding chapter a set of guidelines for service management are presented. The situation differs, of course, between firms and industries. However, some general guidelines for implementing a service strategy can be put forward. These guidelines start from the idea that people are still the critical resource and the bottleneck in most service businesses. However, information technology, the Internet, operational systems and physical resources are increasingly important. So technology and an understanding of how to use it may also be the bottleneck in a service process. As business is a social phenomenon it is, of course, incorrect to talk about any rules of service in a strict sense. Nevertheless, in order to emphasize the common characteristics of the customer relationships in most organizations in service competition, these concluding guidelines have been labelled the seven rules of service. The reader is asked to bear in mind that these rules are general and overemphasize the role of the employees for some situations. The fifth and sixth rules, however, focus on other aspects of service management.

The seven rules of service are as follows:

First rule: The general approach.

Second rule: Demand analysis.

Third rule: Quality control.

Fourth rule: Marketing.

Fifth rule: Technology.

Sixth rule: Organisational support.

Seventh rule: Management support.

FIRST RULE: THE GENERAL APPROACH

The importance of service elements in customer relationships grows over time and customers – business customers as well as individuals – increasingly demand individual and flexible responses from the service provider. Success in the market requires that the firm can offer advice and guidance; for example, technical advice needed to start operating a printer or a production machine, as well as small details, for example, a quick response on the telephone about airplane departure times. If employees are authorized to make their own judgements and have the knowledge needed to do that, and in addition have a service-focused approach to their job and to their customers, and if the firm is competitive in other respects, this will give good results in the marketplace. In spite of automated service systems, the increased use of information technology and the Internet, the creativity, motivation and skills of people are still the drivers behind successful development of new service, the implementation of service concepts and recovery of service failures that occur from time to time. Hence, the first rule of service can be expressed as follows:5

People develop and maintain good and enduring customer contacts. Employees ought to act as consultants, who are prepared to do their duty when the customer needs them and in a way the customer wants. The firm which manages best to do this strengthens its customer relationships and achieves the best profitability.

SECOND RULE: DEMAND ANALYSIS

Service is either rendered directly to people or organizations, or services are made on equipment owned by people (or organizations). In all cases the customer is present, extensively or occasionally, in the service process. Direct interactions between customer contact employees and customers occur, and in such situations immediate actions may have to be decided upon and taken by the contact person, or they may have to provide some information or change their way of doing the job according to the needs of the customer. Such a reaction may be, for example, changing the level of a customer training seminar to better meet the requirements or level of knowledge of the attendees, or a quick decision by a telephone receptionist about whom to put on the phone when the person a customer is asking for is absent. If corrective actions are to be taken immediately, nobody other than the person who produces the service can recognize the perhaps unexpected shift in the needs or wishes of the customer. As has been discussed in previous chapters, in such situations prompt action is called for.

Market demand can, of course, be measured in advance using standard market research. However, the changing needs and wishes of customers at the point and time of service production and consumption cannot be measured in advance. Nor can this be reacted to later on, when somebody else has detected the need for changes in the service process. If the need for a reaction is detected afterwards, the customer relationship was affected long ago. Only customer contact personnel can manage such a situation in a satisfactory manner. Hence, the second rule of service can be expressed as follows:

The customer contact persons producing the service in contact with customers will have to analyse the customers’ activities and processes and their needs, values, expectations and wishes at the point and time of service production and consumption.

THIRD RULE: QUALITY CONTROL

According to traditional manufacturing quality control models, the quality of a product is controlled by a separate unit, which checks the pre-produced goods. This view is no longer valid in modern quality management. Everyone, in manufacturing as well as in service production, has a responsibility for quality, and producing good quality is based on the notion that things will have to be done correctly the first time. Because of the characteristics of service and the nature of service production and consumption, post-production control cannot prevent failure; it can only be observed that bad service quality has been produced and experienced by the customer. Moreover, if things are not done correctly the first time, the cost of correcting quality problems, which have occurred either in the back office or in the service encounter, is frequently high, especially if problems and failures are not rectified immediately. In this scenario the quality goal is often less than 100% and mistakes are therefore tolerated, and these costs easily become ‘hidden costs’, which are taken for granted and considered a necessary evil. It is not possible to have a separate quality control unit following every production step; instead, everyone has to control the result of his job.

In service operations this is very true. In manufacturing, one has to do things right the first time according to static specifications. In service production, as was demonstrated by the discussion of the second rule, the specifications may change during the service process. The customer may change his mind. Technology may break down, or almost anything may happen to change the situation and demand new or unforeseen actions.

The customer contact employee will have to check the quality of the service at the time it is produced and delivered. For example, when goods are delivered to a customer, an elevator is repaired, or a customer in a restaurant is being served, the quality of that service operation cannot be controlled and managed by anyone other than the person who has contact with the customer. Normally, there are no supervisors physically present in employee–customer interactions who can monitor quality on a continuous basis. Afterwards the quality can, of course, be checked, for example by market research, but then the mistake has already been made and the customer relationship may have been damaged.

On the other hand, the contact person must not be left totally alone. ‘Common sense’ may not be sufficient guidance. Management must provide employees with the knowledge, skills and directions needed to manage quality on their own with their customer contacts (internal or external). Moreover, management has to enhance the attitudes and mental capabilities of the employees to manage quality. Hence, the third rule of service can be expressed as follows:

The customer contact person producing the service in contact with customers will have to control the quality of the service at the same time he produces the service.

FOURTH RULE: MARKETING

In service competition the nature of marketing changes as well. Although traditional external marketing activities, such as market research, advertising campaigns, pricing, personal selling by a professional salesforce and sales promotion, are as important as ever, they are not the only activities to be performed as marketing activities. The marketing process is much broader and is spread throughout the organization. When ongoing relationships are to be maintained and strengthened, traditional marketing efforts are of less importance. In order to develop existing customer relationships, the exchange of goods, services and information, as well as financial and social exchange, is of critical importance. Personal selling, advertising and sales promotion activities are, of course, used in such situations, too, but their impact is often minor. Price is important at all stages of the customer relationships lifecycle.

In service competition every contact between a contact person and a representative of a customer includes an element of marketing. These contacts are the moments of truth or the moments of opportunity where the success of the service provider is determined, and resales and cross-sales opportunities can be utilized. If these moments of truth give the customer a favourable impression of the contact person, of the systems and resources used, and thus of the total organization, the customer relationship is strengthened. The probability that it will last longer and lead to further business increases. However, the opposite is also true. Badly-handled service encounters – that is, negatively experienced moments of truth – damage customer relationships and lead to lost business. They are truly missed moments of opportunity.

Any service organization has a large number of part-time marketers. However, marketing is only their second responsibility, beside the tasks they are set to perform. If the marketing aspect of their job is neglected, customers will perceive the quality of the service more negatively. Furthermore, in almost every service organization the part-time marketers outnumber the full-time marketers and salespeople several times over.6 Consequently, the marketing impact of what they do and how they perform their tasks has to be recognized by management, because their role in the total marketing process is critical. If the interactive marketing performance of the part-time marketers fails, the marketing process fails, irrespective of whether the efforts of the salesforce or the advertising campaigns or other traditional external marketing efforts have been successful or not. This is the essence of service marketing. Marketing the service as a part-time marketer in the interactive marketing sense does not necessarily mean that the contact person would have to actively sell or offer the service, although this may also occur. Normally good part-time marketing behaviour means that the job is done skilfully, in a flexible manner, without unnecessary delays, and with a service-focused attitude. Hence, the fourth rule of service can be expressed as follows:

The customer contact person has simultaneously to be a marketer of the service he produces.

FIFTH RULE: TECHNOLOGY

Information technology is becoming exceedingly important for more and more service processes. If a website is designed so that users find it complicated or uninteresting, or if people using a website do not get a quick response to their inquiries, they quickly lose interest in the firm and its offerings; it is so easy to jump to the next website. Information technology should also enable contact employees to get easily retrievable and reliable information about the customers they are serving. If that is not the case, interactions between contact employees and customers are affected and bad perceived quality created.

All kinds of technology and physical resources used in service processes must be customer-friendly and reliable. A technological solution, or a physical resource that is geared to the needs and wishes of the user and that fits the situation in which it is to be used, may well enhance the quality of the service. It can improve the efficiency of operations and profitability as well. Even more frequently, technological support enables personnel to produce a better service. Appropriate technology and physical resources, such as computer systems, documents, tools and equipment, may at the same time improve working conditions and enhance the motivation of the employees to give good service. On the other hand, technology that employees do not understand or are not willing to use has a negative effect both on internal relationships in the organization and on external customer relationships. Employees need adequate technological support.

Hence, the fifth rule of service can be expressed as follows:

The impact on customers’ ability and willingness to use technology, systems and physical resources (of any kind), as well as the impact of such resources on the employees in interactive and supporting parts of the organization, and on their ability and willingness to serve customers, have to be taken into account when investments in such resources are made, so that the service orientation of employees and the service quality perceived by customers are not affected in a negative way.

SIXTH RULE: ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE SUPPORT

In many firms the organizational structure does not support customer-focused and high-quality service operations. Contact employees and departments that have to interact with each other in order to produce a service may be geographically or physically far apart in the organization. Often decisions concerning even minor details are made too far away from the service encounter which, of course, can have a negative impact on the perceived service. Internal regulations may restrict the flexibility of the contact staff. For example, hotels frequently have their employees say, ‘No, sir, we cannot do that – management regulations, sir’ to customers who ask for a service outside the normal procedures. Trousers cannot be ironed on a Sunday, or pyjamas cannot be supplied for a guest whose luggage has been left behind by an airline, or because designated exit gates are elsewhere an entry gate to an attraction cannot be opened to let an exhausted visitor out quickly. Management does not trust employees to think for themselves and make sensible decisions.

In many manufacturing firms, service elements are considered to be low priority. This means that services are not, like goods, an integral part of the total offering to the market. They receive fewer resources and less of management’s time.

The employees and their managers alike often feel that service is not important. A company’s organizational structure may not be geared to the demands of the new service competition. The result is inevitable, of course. Employees involved in the firm’s variety of service operations feel no pride in their job, nor do they feel motivated to provide good service to customers. In order to develop their service into powerful means of competition, firms will have to adjust their structure so that the organization supports employees in their efforts to provide good service. An organizational structure support is needed.

Hence, the sixth rule of service can be expressed as follows:

The organizational structure must enable internal collaboration between employees and departments and motivate customer contact personnel and support personnel alike, such that good service can be provided to internal and external customers.

SEVENTH RULE: MANAGEMENT SUPPORT

It is well known that managers and supervisors get the staff they deserve. They have an important effect on the values that guide the overall way of thinking and behaving in the organization. In service competition this is as true as it ever was, and even more important to realize than before, because of the immediate impact that contact persons have on demand analysis, quality control and marketing.

Managers and supervisors have to be true leaders, not simply technical managers. There are too many rules and restrictions that managers and supervisors use as managing devices. If employees are well informed and have required skills, they are normally able to think for themselves, act spontaneously and in a flexible manner, and still make good judgements. Such service-oriented attitudes are effectively damaged by too much rules-and-regulation management and too little leadership.

Managers have to be able to motivate their people to be service-oriented and customer-focused, by, for example, their leadership style, their way of sharing information and giving feedback to people in their organizational unit, and their way of encouraging, supporting and guiding employees. They will have to demonstrate, by the way they do their job, that they, too, consider good service and satisfied customers important. It goes without saying that this attitude is required of every manager in the firm, irrespective of their hierarchical position and their own involvement in service operations.

Unclear visions and/or badly defined or undefined service concepts (one or several) make it difficult for managers, supervisors and support and customer contact employees to decide in which direction they should go, what leads to fulfilling goals, and what is contradictory to the objectives of the organization. If service concepts are not well stated, no clear goals can be set. In such situations there will be disarray both in planning and in the everyday implementation of plans. To sum up, the employees need the management support of their managers and supervisors. Moreover, clearly defined service concepts are a necessity if the organization is to avoid a chaotic situation where nobody knows what to do in certain situations or how to react to changes in the environment and to unexpected customer behaviour. Hence, the seventh rule of service can be expressed as follows:

Every manager and supervisor, and explicitly defined service concepts, have to provide the guidance, support and encouragement needed to enable and motivate customer contact persons and support persons alike to provide good service.

FIVE BARRIERS TO ACHIEVING RESULTS

The last three rules can be made more explicit by adding five additional statements that follow directly from the discussion about these rules. These statements all concern major barriers to successfully implemented service management. Most of these are due to an outdated management philosophy and old organizational structures, which hamper the development of sound and effective management of firms in the post-industrial society of the 21st century.8 They are:

Organizational barrier.

Systems and regulations-related barrier.

Management-related barrier.

Strategy-related barrier.

Decision-making barrier.

Barrier 1 (organizational barrier). Good service, and sound change processes towards a service culture, are effectively destroyed by an old-fashioned and obsolete organizational structure. If an inappropriate organizational structure is left outside a change programme, much of the effort to achieve better service may be in vain. The organization simply is not suitable for service and, thus, becomes a barrier to change.

Barrier 2 (systems and regulations-related barrier). Employees would normally like to treat their customers well and provide good service, but internal rules and regulations, the systems of operating, and the technology used may make this an impossible task. It is only natural that most people would prefer to treat their customers well and provide good service, but if management regulations, operational or administrative systems, or the technology used counteract good service, they cannot do this. The internal infrastructure becomes a barrier to change. This typically happens when training efforts are used in isolation as the major or only means of developing a service culture in an organization, and no attention is given in the change process to this infrastructure provided by regulation, systems and technology.

Barrier 3 (management-related barrier). How managers treat their staff is the way the customers of the organization will be treated. If a change process focuses predominantly or only on contact and support personnel and top and middle management are left outside, there is a risk that the superiors of those involved in customer contacts will not be fully aware of what should be emphasized in these contacts and how the moments of truth should be handled and managed. Supervisors can easily encourage the wrong aspects of a task, and a role conflict emerges for the employees. They would like to implement new ideas, but their bosses have become a barrier to doing this.

Barrier 4 (strategy-related barrier). If well-defined and easily understood service concepts are lacking, chaos will reign in the organization, and managers and customer contact and support persons alike will be uncertain about how to act in specific situations, in planning as well as in implementing plans. If the organization throws itself into a change process without first clearly analysing the benefits sought by the customers in the organization’s target segments, and decides what it should do, and how corresponding goals should be accomplished, there is no solid foundation for a consistently pursued change process. A number of projects are initiated and programmes started without anyone really knowing why this is being done and what the ultimate objectives are. In short, there is no strategic approach, and this becomes a barrier to change.

All of the four barriers above, as well as the six rules, are easy to accept, and generally it is not difficult for managers to admit that these rules have been broken and/or several barriers to change are present in their organizations. However, there is a big step from understanding a phenomenon and accepting that a problem may exist to doing something about it. Therefore, a fifth barrier is finally offered as the key to success.

Barrier 5 (decision-making barrier). Good intellectual analysis and thorough planning is of no value unless there is the determination, courage and strength needed in the organization to implement new visions and intellectually sound plans. To put this another way, weak management is always a barrier to implementing change processes.

NOTES

1. See Grönroos, C., Relationship marketing: challenges for the organization, Journal of Business Research, 46(3), 1999, 327–335.

2. Grönroos, op. cit. One of the major Scandinavian banks referred to in previous chapters of this book has long ago abolished the use of the term ‘marketing’ for the customer management process. In that bank the term ‘active customer contact behaviour’ was introduced instead. This change of terminology turned out to be successful. There are also other examples.

3. However, as the author believes that it is only fair to say that the term ‘marketing’ is outdated and does not fit an era of service competition and a service and relationship perspective in customer management, he would have liked to use another term which more appropriately would fit today’s situation in the marketplace.

4. See Strandvik, T., Holmlund, M. & Grönroos, C., The mental footprint of marketing in the boardroom. Journal of Service Management, 25(2), 2014, 241–252, where problems with the term ‘marketing’ are discussed.

5. The logic underpinning this general rule of service was discussed by Gösta Mickwitz in an essay on the role of service in business. See Mickwitz, G., Arbetstid och service (Working hours and service). Ekonomiska Samfundets Tidskrift (The Journal of the Economic Society of Finland), 38(4), 1985, 163. In Swedish. Gösta Mickwitz is a former Professor of Marketing and Economics at Hanken School of Economics and Helsinki University in Finland and my mentor, who taught me to think laterally and seek solutions outside the limits set by the prevailing opinion.

6. Gummesson, E., Marketing revisited: the crucial role of the part-time marketer. European Journal of Marketing, 25(2), 1991, 60–67.

7. Murphy, P., Front stage transactions lead to backstage relationships: a study of role repertoires in hospital service provision. Unpublished research paper. Dundee University, Scotland, UK, 2000.

8. Grönroos, C., Företagsledningens tvångströja (The management straitjacket). Ekonomiska Samfundets Tidskrift (The Journal of the Economic Society of Finland), 52(3), 1999, 115–116. In Swedish.

9. See, for example, Grönroos, C., Adopting a service logic for marketing. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 2006, 317–333, and Grönroos, C. & Voima, P., Critical service logic: making sense of value creation and co-creation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(2), 2013, 133–150.

FURTHER READING

Grönroos, C. (1999a) Relationship marketing: challenges for the organization. Journal of Business Research, 46(3), 327–335.

Grönroos, C. (1999b) Företagsledningens tvångströja (The management straitjacket). Ekonomiska Samfundets Tidskrift (The Journal of the Economic Society of Finland), 52(3), 115–116. In Swedish.

Grönroos, C. (2006) Adopting a service logic for marketing. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 317–333.

Grönroos, C. & Voima, P. (2013) Critical service logic: making sense of value creation and co-creation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(2), 133–150.

Gummesson, E. (1991) Marketing revisited: the crucial role of the part-time marketer. European Journal of Marketing, 25(2), 60–67.

Mickwitz, G. (1985) Arbetstid och service (Working hours and service). Ekonomiska Samfundets Tidskrift (The Journal of the Economic Society of Finland), 38(4), 163.

Murphy, P. (2000) Front Stage Transactions Lead to Back Stage Relationships: A Study of Role Repertoires in Hospital Service Provision. Unpublished research paper. University of Dundee, Scotland, UK.

Strandvik, T., Holmlund, M. & Grönroos, C. (2014) The mental footprint of marketing in the boardroom. Journal of Service Management, 25(2), 241–252.