CHAPTER 14

PEOPLE MANAGEMENT: INTERNAL MARKETING AS A PREREQUISITE FOR SUCCESSFUL CUSTOMER MANAGEMENT

“Without good and well-functioning internal relationships, external customer relationships will not develop successfully. Engaging and motivating employees – on all levels – is a true test of managing an organization.”

INTRODUCTION

In service businesses in particular the role of employees is paramount for success. In spite of the growing importance of technology, customer-centric and service-minded employees are needed for high-quality service experiences. Therefore, successful people management is a prerequisite for successful customer management. This chapter will discuss a phenomenon that was originally highlighted by the research into service marketing; that is, internal marketing.1 Throughout this book, the issue of internal marketing has emerged in several contexts. The term was coined as an umbrella concept for a variety of internal activities and processes that are not new but, focused upon as here, offer a new approach to developing a service orientation and an interest in customers and marketing among an organization’s personnel. Internal marketing starts from the concept that employees are a first, internal market for the organization. If a service perspective, goods, services, planned marketing communication, new technologies and operational systems cannot be marketed to this internal target group, marketing to ultimate, external customers cannot be expected to be successful either. Internal marketing is a prerequisite for successful external and interactive marketing. The latter part of the chapter will focus upon two concepts that are closely related to internal marketing, empowering and enabling employees. After reading this chapter the reader should understand the role of internal marketing in service management and know how to develop an internal marketing process, as well as understand the opportunities for empowerment and the risks related to half-hearted empowerment processes.

INTERNAL MARKETING: A SUMMARY

Internal marketing is not a new phenomenon, and it was not new when the term was first used in the service marketing literature in the 1970s.2 Firms have always used morale-boosting activities and campaigns, and employees’ attitudes and motivation have long been a concern of management and human resources staff. However, the notion of internal marketing has brought three new aspects to human resources management in a firm:

The employees are a first, internal market for the firm’s offerings to external customers as well as for its external marketing programmes.

An active, co-ordinated and goal-oriented approach to all employee-oriented efforts, which combines these internal efforts and processes with an external orientation of the firm (that is, with creating a preparedness and motivation for good interactive marketing behaviour and provision of good perceived service quality).

An emphasis on the need to view people, functions and departments internal to the firm as internal customers, to whom internal service has to be provided in the same customer-focused manner as to external customers.

The first observation is important, because it points out the fact that everything the service provider does for its external customers (planned marketing communication, service offerings, etc.) is first perceived and evaluated by its own personnel. If employees do not believe in the promises made by external marketing activities and campaigns, do not know how to implement a service offering or how to make use of technology or systems in the service process – if they do not accept them, or feel that they do not have the skills to perform according to what is required of them, they will not ‘buy the offering’. In that case they will not be able or willing to perform as effective part-time marketers and contribute to a good interactive marketing impact and successful brand fulfilment. The employees form an internal market that should be attended to first.

The second notion is equally important, because it emphasizes the fact that all internal efforts, programmes and processes have to be geared towards maintaining or improving external effectiveness and the firm’s external performance. Human resource management is not only an internal matter, but is also a matter of making sure that employees contribute to the service provider’s external performance. Such efforts and processes have to be planned and implemented with a similar approach as external marketing, that is, in a co-ordinated, active and goal-oriented way.

The third observation – that internal customers exist and that they have to be treated in the same way as external customers – has an important impact on the internal relationships of an organization.3 Fellow employees must not be provided with slow, inattentive and careless service and support, because if this is the case their ability to provide the firm’s ‘real’ customers with good service and to create high perceived service quality is seriously jeopardized.

Internal marketing studies4 have emphasized a need to view people in an organization not only as individuals but as relationship partners, and moreover pointed out that people management has to reach out to people in relationships with other organizations in the network as well.5

What is required of the employees in a customer-focused and service-oriented organization.

General requirements: • Understand the full relationship the firm has with its customers (or other stakeholders). • Understand and accept their role and obligations in maintaining these relationships. • Be customer-focused in their work environment. Specific requirements: • Have the skills to interact and communicate with customers (or other stakeholders). • Be motivated to interact and communicate. • Feel rewarded for interacting and communicating in ways that support customer-focused behaviour and thus successful interactive marketing performance. |

The first observation emphasizes the need to view employees not as subordinates but from a win–win partnering perspective, where people feel that they are working for an organization that provides them with something in return, such as opportunities to develop, an encouraging environment, access to skills, information and support from a knowledge-generating team, and of course an acceptable salary.6

The second observation demonstrates that the borderline between what is inside an organization and what is outside it becomes blurred. The distinction between relationships with employees internal to a firm or to a network and relationships with customers and other stakeholders becomes blurred as well. Suppliers, service providers and their customers become one interactive organization, where value for customers is created jointly in interactive relationships.

Recent research into internal marketing has pointed out that the notion of motivating employees and creating motivated employees, which has been suggested as a key goal of internal marketing, easily becomes an obstacle for lifting people management onto a strategic level in an organization.7 Neither top management nor marketing specialists tend to consider motivating employees part of their responsibilities, or even an issue they should be concerned about. As a consequence motivating employees remains a tactical issue in the firm. This observation is important, because the internal marketing approach to people management considers motivating employees for customer-focused and service-minded behaviour of such importance to success that it should be given strategic attention.

In Table 14.1 what is required of employees for a service firm to be customer-focused and service-oriented is illustrated. These requirements can be divided into general requirements and specific requirements. In subsequent sections, means of achieving the goals set by these requirements will be discussed at length.

INTERNAL MARKETING: A STRATEGIC ISSUE

The term internal marketing was originally derived from the notion of the internal market of employees, and from this point of view internal marketing is a logical term. However, it can be argued that this term is not very appropriate. Often employees who have no marketing training and who do not consider themselves part of marketing, and normally have not been appointed to be concerned with customers as part-time marketers, have a negative view of marketing and do not want to be involved in anything labelled marketing. Why should they want to be involved in something called ‘internal marketing’? If the term becomes a problem internally, one can always choose another name for this phenomenon for internal use. Many firms have done so, and any term or slogan that functions well will do. However, the term internal marketing is used to describe this approach to people management in principle, what it includes and how it can be implemented. Therefore, the term internal marketing is used in this book as well.

Human resources form a strategic resource for any firm. With employees who are inadequately trained, have poor attitudes towards their job and towards internal and external customers, and who get inadequate support from systems, technologies, internal service providers and their managers and supervisors, the firm will not be successful. Therefore, internal marketing is a management strategy.8 It is a strategic issue, in spite of the development of information technology and the growth of high-tech service. If top management does not understand the strategic role of people and consequently also of internal marketing, money invested in internal marketing efforts and processes will not pay off. In that case money invested in information technology and systems often does not pay off very well either. The active and continuous support of top management, not merely lip service to the importance of employees, is a necessity for successful internal marketing.

In internal marketing the focus is on good internal relationships between people at all levels in the organization, such that a service-oriented and customer-focused mindset is created among customer contact employees, support employees in internal service processes, team leaders, supervisors and managers. However, such a mindset is not enough. Adequate skills (for example, for how to interact and communicate with customers) and supportive systems and leadership are also required. If employees do not have the knowledge and skills needed to provide good service and create a favourable marketing impact, they will not be motivated to perform in that way.

Top management, human resource management and marketing all contribute to the implementation of internal marketing processes. They do so in close collaboration with service operations and other departments, where part-time marketers work.9 As will be seen later in this chapter, on a tactical level many of the activities of internal marketing already exist in firms. It is only a matter of refocusing, co-ordination, and active and goal-oriented implementation. However, on a strategic level the role and importance of internal marketing is often not yet properly recognized.

Internal marketing thus operates as a holistic management process to integrate multiple functions of the firm in two ways. First, it ensures that employees at all levels in the firm (including management) understand the importance of a customer focus in the business and its various processes, activities and campaigns. Second, it ensures that all employees have adequate knowledge and skills for complete customer support and are prepared and motivated to act in a service-oriented manner.

THE INTERNAL MARKETING CONCEPT

The emerging importance of service to almost every business has enhanced the notion that a well-trained and service-focused employee, rather than raw materials, production technology or the products themselves, is the most critical resource. These employees will be even more critical in the future in an increasing number of industries. The more information technology, automated and self-service systems are introduced in service processes, the more important will be the service orientation and customer-consciousness of the employees who remain. The customer contacts that occur from time to time will have to be consistently perceived favourably by the customers. In such service processes, the high-tech processes are largely taken for granted, whereas contacts with service employees, when they occur, either make or break the customer relationship.

Marketing specialists in the marketing department are not the only human resource in marketing; often they are not even the most important resource. In customer contacts, these full-time marketing specialists are almost always outnumbered by employees whose main duties are production and operations, deliveries, repair and maintenance services, claims handling or other tasks traditionally considered non-marketing. However, the skills, customer focus and service-mindedness of these individuals are all critical to customers’ perception of the firm and to their future patronage. Hence, customer focus and a willingness to serve customers in a marketing-oriented fashion and to provide customer satisfaction have to be spread throughout the organization, to every department and work group.10

The internal marketing concept states that:

The internal market of employees is best motivated for service-mindedness and prepared for customer-focused performance by an active, goal-oriented approach, where a variety of activities and processes, on a strategic as well as operational level, is used internally in an active, marketing-like and co-ordinated manner. In this way, internal relationships between people in various departments and processes (customer contact employees, internal support employees, team leaders, supervisors and managers) can best be enhanced and geared towards service-oriented management and implementation of external relationships with customers and other parties.

Internal marketing is the management philosophy of treating employees as customers.11 They should feel satisfied with their job environment and relationships with their fellow employees on all hierarchical levels, as well as with their relationship with their employer as an organization. Human resource management (HRM) and internal marketing are not the same thing,12 although they have a lot in common. HRM offers tools that can be used in internal marketing, such as training, rewarding, hiring and career planning, and adds more tools. Internal marketing offers guidance on how these and other tools should be used, that is, to improve interactive marketing performance through customer-focused and skilful employees. Successfully implemented internal marketing requires that marketing and HRM work together.13

What is new with the internal marketing concept as described in this chapter is the introduction of a unifying concept for more effectively managing a variety of interfunctional and well-established activities as part of an overall process aimed at a common objective. The importance of internal marketing is the fact that it allows management to approach all of these activities in a more systematic and strategic manner and gear them towards the external performance of the firm. Internal marketing is not legitimated by its methods – any activity could be part of internal marketing – but by its purpose of gearing internal personnel-oriented processes towards their external customer-focused effects (or internal customer-oriented effects).14

TWO ASPECTS OF INTERNAL MARKETING: CHANGING ATTITUDES AND COMMUNICATING CHANGES

Internal marketing means two types of management processes, changing attitudes (attitude management) and communicating changes (communications management). First of all, the attitudes of employees and their motivation for customer-focus and service-mindedness have to be managed. This is often the predominant part of internal marketing.

Second, managers, supervisors, contact people and support staff need information to be able to perform their tasks as leaders and managers and as service providers to internal and external customers. They need information about job routines, goods and service features, promises given to customers by, for example, advertising campaigns and salespersons, and so on. They also need to communicate with management about their needs and requirements, their views on how to improve performance, and their findings of what customers want. This is the communications requirement of internal marketing.

Both attitude management and communications management are necessary if good results are to be expected. Too often only the communications issues are recognized, and perhaps only as a one-way information task. In such cases, internal marketing typically takes the form of campaigns and activities. Internal brochures and booklets are distributed to personnel, and staff meetings are held where written and oral information is given to the participants and very little communication occurs.15 Also, managers and supervisors typically take limited interest in their staff and do not recognize their need for feedback information, two-way communication, recognition and encouragement. The employees receive an abundance of information but very little encouragement. As a result, there is not much mutual understanding

This, of course, means that much of the information they receive has no major impact on the staff. The necessary change of attitudes and enhancement of motivation for good service and customer consciousness is lacking, and employees are, therefore, not receptive to the information.

If the need for and the nature of the attitude management aspect of internal marketing is recognized and taken into account, internal marketing becomes an ongoing process instead of a campaign or series of campaigns, and the role of managers and supervisors, on every level, is much more active. Also, much better results are achieved.

Changing attitudes always includes an element of reinforcing newly instilled attitudes, and is, therefore, a continuous process, whereas communications management may be more of a discrete process including activities at appropriate points in time. However, these two aspects of internal marketing are also intertwined. Naturally, much or most of the information shared with employees has an effect on attitudes. For example, customer contact personnel who are informed in advance about an external advertising campaign develop more positive attitudes towards fulfilling the promises of that campaign. The tasks of managers, supervisors and team leaders include, as integral and often inseparable parts, both communications management aspects and attitude management aspects.

PURPOSE AND OVERALL OBJECTIVES OF INTERNAL MARKETING

Internal marketing has almost always been described as a means of motivating employees to be customer-focused and service-minded in their customer contacts. This makes sense, but given that internal marketing should be on top management’s agenda as a strategic issue, and that top management does not usually take an explicit interest in motivating employees, defining internal marketing in this way does not seem appropriate. Instead, as Laura Cacciatore16 suggests in her study of the subject the lack of adequate knowledge and skills, which is a major reason for lack of motivation for customer-focused and service-minded behaviour among employees, could be the key focus of internal marketing. The competence level and the development of appropriate knowledge, skills and abilities among the employees are issues which have the potential to draw top management’s attention and turn internal marketing into a strategic issue.

A main reason why employees are not motivated to perform in a certain manner – customer-focused, service-minded, or any other way – is a lack of knowledge and skills that would be required for them to feel comfortable with a given behaviour. Provided that a wanted behaviour is considered generally acceptable by the employees, closing this competence gap can be expected to create motivation and a willingness to perform. However, as will be discussed in subsequent sections of this chapter, closing such a competence gap is a continuous process, where a number of strategic and tactical issues have to be considered. On a general level the purpose of internal marketing can be defined as follows:17

The purpose of internal marketing is to close the gap between the skills, knowledge and competencies that employees need to successfully provide customers with good service, and the current competence level (e.g. knowledge and skills) and support provided (e.g. management, information and physical support) in the organization.

Closing the competence gap can be expected to contribute to the desired motivation for a wanted behaviour. There are of course also other reasons for a lack of motivation. However, as will be shown in subsequent sections, creating, reinforcing and maintaining adequate knowledge and skills demand a set of actions which address other motivators as well, such as management and supervisory behaviour, communicating with employees and ways of disseminating information, and ways of including employees in planning processes.

Based on the purpose of internal marketing formulated above, from a relationship perspective, the objective of internal marketing is:

...to create, maintain and enhance internal relationships between people in the organization, regardless of their position as customer contact personnel, support personnel, team leaders, supervisors or managers, so that they have the skills and knowledge required as well as the support needed from managers and supervisors, internal service providers, systems and technology to be able to provide service to internal customers as well as to external customers in a customer-focused and service-minded way, and feel motivated to perform in such a manner.18

Such internal relationships can only be achieved if employees are comfortable with what is required of them and feel that they can trust each other, and above all trust the firm and its management to continuously provide the physical and emotional support required to perform in a customer-focused and service-minded way.19

From the relationship-oriented objective of internal marketing, four more specific overall objectives can be derived:

To ensure that employees are motivated for customer-focused and service-minded performance and thus successfully fulfil their duties as part-time marketers in the interactive marketing process.

To attract and retain good employees.

To ensure that internal service is provided in a customer-oriented manner in the organization or between partners in a network.

To provide people who render service internally or externally with adequate managerial and technological support, which enables them to fulfil their responsibilities as part-time marketers.

The main objective is, of course, to create an internal environment and implement internal actions, processes and programmes so that employees feel motivated to carry out part-time marketing behaviour. However, the second objective follows on from the first one: the better its internal marketing works, the more attractive the firm is considered as an employer. The third objective is, of course, only an extension of the first one, and the fourth objective is a requirement for maintaining a motivation for customer orientation as well as for making it possible to perform well in a practical situation as a part-time marketer. These overall objectives can be developed into more specific goals depending on the situation at hand. This will be discussed in the following sections.

THE THREE LEVELS OF INTERNAL MARKETING

In principle, three different types of situation can be identified where internal marketing is called for:

When creating a service culture in the firm and a service orientation among personnel as the fundamental requirement for the existence of customer-focused and service minded behaviour among employees on all levels.

When maintaining a service orientation among personnel.

When introducing a service perspective, new goods and services or external marketing campaigns and activities or new technologies, systems or service process routines to employees.

These situations represent three levels of internal marketing. Each of the situations will be discussed below.

CREATING A SERVICE CULTURE

As will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 15, a service culture exists when a service orientation and an interest in customers are the most important norms in the organization.

In many firms a service culture is lacking or weak. Internal marketing is a powerful means of developing a service culture in connection with other activities. In Chapter 16 service culture and how to create such a culture is discussed. In general, internal marketing goals in this situation are:

To enable employees – managers, supervisors, customer contact employees and support employees – to understand and accept the service perspective and business mission, strategies and tactics as well as the goods, services, external marketing campaigns and processes of the firm.

To create positive relationships between people in the organization.

To develop a service-oriented management and leadership style among managers and supervisors.

To teach all employees service-oriented communications and interaction skills.

It is essential to achieve the first goal, because one cannot expect employees to understand why service, service orientation and customer consciousness are important and why they have responsibilities as part-time marketers, unless they are aware of what the firm wants to achieve, and accept this. The second goal is important, because good external relationships with customers and other parties are dependent on the internal climate in the organization. The third and fourth goals are important because service-oriented management methods and communication and interaction skills are fundamental requirements of a service culture.

MAINTAINING A SERVICE CULTURE

The second situation where internal marketing can be useful is when a service culture should be maintained. Once such a culture has been created it has to be maintained in an active manner, otherwise employees’ attitudes will easily revert to a culture where non-service norms and a lack of customer focus dominate. Internal marketing goals for helping to maintain a service culture include the following:

To ensure that management methods are encouraging and enhance the service-mindedness and customer focus of employees.

To ensure that good internal relationships are maintained.

To ensure that an internal dialogue is maintained and employees receive continuous information and feedback.

To continuously market new goods and services as well as marketing campaigns and processes to the employees before they are launched externally.

The most important internal marketing issue here is the management support of every single manager and supervisor. Management style and methods are of extreme importance at this point. Employees seem to be more satisfied with their jobs when supervisors concentrate on supporting how problems for customers are solved rather than enforcing existing rules and regulations.

Because management does not have the ability to directly control service processes and the moments of truth of the service encounters, it has to develop and maintain indirect control. Such indirect control can be established by maintaining a culture that makes employees feel that service should guide their thinking and behaviour.20 In this continuous process, every single manager and supervisor is involved. If they are able to encourage their staff, if they can open up communication channels – both formal and informal – an established service culture can be expected to continue. Managers and supervisors are instrumental in maintaining good internal relationships.

INTRODUCING NEW GOODS, SERVICES, EXTERNAL MARKETING ACTIVITIES, CAMPAIGNS AND PROCESSES

Internal marketing initially emerged as a systematic way of handling problems when firms planned and launched new goods, services or marketing campaigns without properly preparing their employees. Contact employees especially could not perform well as part-time marketers when they did not know what was going on, did not fully accept new goods, services or marketing activities, or learned about new services and advertising campaigns from newspaper adverts or TV commercials or, even worse, from their customers.

It should be noted that this third level of internal marketing is interrelated with, and reinforces, the other two. These introductions, however, form an internal marketing task in their own right. At the same time, they enhance the maintenance of an established service culture or support the establishment of such a culture. The internal marketing goals for helping with these introductions of new goods, services and external marketing campaigns and processes include the following:

To make employees aware of and accept new goods and services being developed and offered to the market.

To make employees aware of and ensure their acceptance of new external marketing campaigns and activities.

To make employees aware of and accepting of new ways – utilizing new or renewed technologies, systems, routines, etc. – in which various tasks influencing internal and external relationships and interactive marketing performance are to be handled.

PREREQUISITES FOR SUCCESSFUL INTERNAL MARKETING

If internal marketing activities are implemented purely as isolated programmes or campaigns, or, even worse, as separate activities without connections to other management factors, the risk that nothing enduring will be achieved is overwhelming. The organizational structure and the strategy of the firm have to support the establishment of a service culture. Moreover, management methods and the management and leadership style of managers and supervisors have to be supportive if they are to be expected to fulfil their tasks in internal marketing.

The three prerequisites for successful internal marketing are:

Internal marketing has to be considered an integral part of strategic management.

The internal marketing process must not be counteracted by the organizational structure of a firm or by lack of management support, or systems and physical support.

Top management must constantly demonstrate leadership and active support for the internal marketing process.

In order to be successful, internal marketing starts with top management. Next, middle management and supervisors have to accept and live up to their role in a marketing process. Only then can internal marketing efforts directed towards contact employees and support employees be successful. Employees’ ability to function as service-minded part-time marketers depends to a large extent on the support and encouragement they get from supervisors. Genuine customer-focused leadership at all levels in the organization is a necessity if customer contact and support employees are expected to be committed to good service.

In conclusion, all other categories of employees have to be involved as well. The contact personnel form a natural target market for internal marketing. They have the immediate customer contacts and are instrumental in the interactive marketing process. However, they often depend on support from other employees and departments in the firm. The ability of contact employees to perform their interactive marketing tasks depends to a large extent on the service-mindedness of employees who do not come into contact with customers themselves. Such groups of employees, the support personnel, should perform in a customer-focused manner when they serve their internal customers (for example, contact employees). They are part-time marketers as well, although their customers are internal and not external. In summary, the four main target groups for internal marketing are:

Top management.

Middle management and supervisors.

Customer contact personnel.

Support personnel.

It should be noted that the same person may occupy several positions. A support person may sometimes be a contact person. A supervisor who, for example, is supposed to support and encourage contact people may be a contact person serving customers, or a support person serving internal customers, regularly or occasionally. Middle or top management may also have customer contacts. When they have such contacts they, too, are part-time marketers in the firm’s marketing process.

STRATEGIC AND TACTICAL INTERNAL MARKETING

As internal marketing is part of strategic management, and therefore should be a management philosophy, implementing internal marketing includes strategic aspects as well as tactical ones. On a strategic level internal marketing requires that management creates a job environment which is encouraging and motivating for customer-focused and service-minded behaviour.21 On a tactical level, internal marketing activities which aim at implementing a customer-focused, service-minded behaviour are planned and executed.

STRATEGIC INTERNAL MARKETING

In order for management to create a motivating and encouraging environment for service-oriented and customer-focused behaviour, four management areas are important. These are:

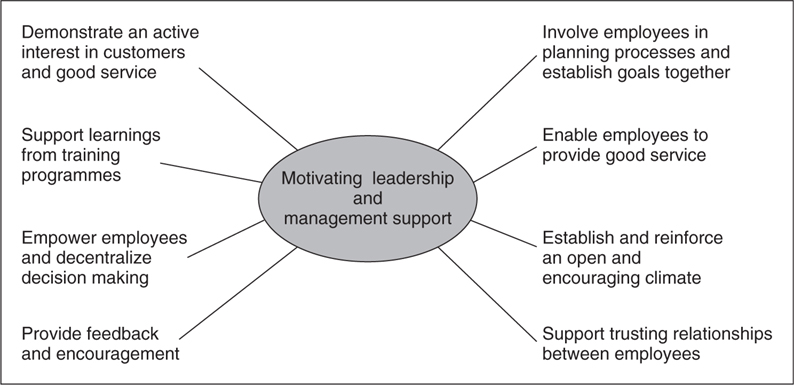

Motivating leadership and management support.

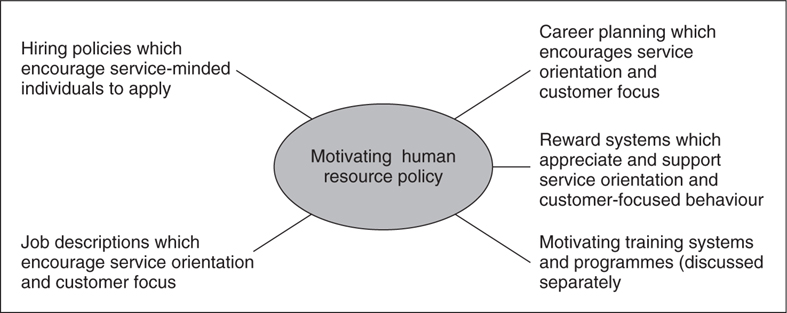

Motivating human resource policy.

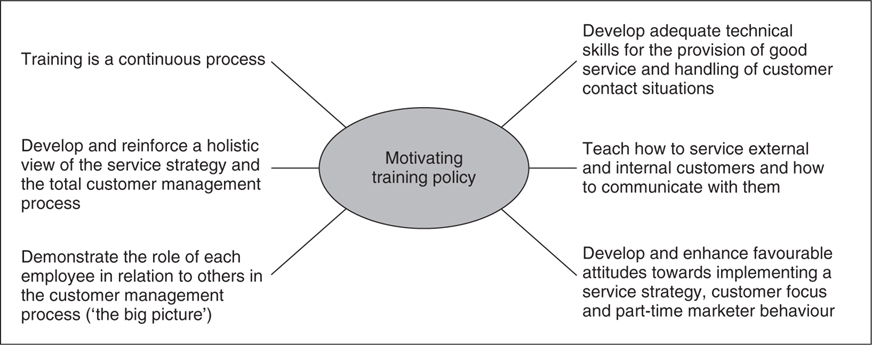

Motivating training policy.

Motivating planning systems.

In the following sections we shall discuss these in some detail.

MOTIVATING LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT SUPPORT

Training is an important internal marketing activity. However, no training programme alone is enough in an internal marketing process. In order to achieve continuity in such a process, the role of top management, middle management and supervisors is paramount. Managers, supervisors and team leaders have to show leadership, not only administrative ‘managing and controlling’.

Management support can be of various types, for example:

• Continuity of formal training programmes by everyday management actions.

• Demonstrating an active interest in customers and in providing good service.

• Actively encouraging employees as part of everyday management tasks.

• Empowering employees by giving them decision-making authority, and thereby showing trust in them.

• Involving employees in planning and decision-making.

• Feedback to employees and flow of information and two-way communication in formal and informal interactions.

• Establishing an open and encouraging internal climate.

• Creating trusting relationships among employees.

Frequently, employees returning from a course or a training session have no follow-up on the course message. Their supervisor is not interested in what they have learned or how to make use of new ideas and knowledge. Employees are usually left alone to implement what they have learnt. Sometimes employees get the impression that the fact they have been away for training has only created problems, for example with undercapacity. Nobody seems to care about any positive and potentially useful learnings. In such situations, employees are alienated, any new idea and favourable attitude effects are rapidly destroyed.

Instead, the manager or supervisor should encourage employees to implement new ideas and help them to realize how they could be applied in their specific environment. Recognition is a critical part of management support. The management style demonstrated daily by managers and supervisors has an immediate impact on the job environment and internal climate, thus management style is an internal marketing issue.

FIGURE 14.1

Strategic internal marketing: Motivating leadership and management support.

Joint planning and decision-making with the employees involved is a means of achieving commitment in advance to further actions that emerge from the planning process. Customer contact employees have valuable information and knowledge of the needs and desires of customers, so the involvement of these employees in the planning process leads to improved decision-making.

The need for information and feedback has been discussed already in this book. Here, managers, especially supervisors, have a key role. Moreover, they are responsible for creating an open climate where service-related and customer-related issues can be raised and discussed in a relationship-enhancing internal dialogue.

Management support and internal dialogue are the predominant tools of the attitude management aspect of internal marketing, but they are also key ingredients of communications management.

Key aspects of motivating leadership and management support as part of strategic internal marketing are summarized in Figure 14.1.

MOTIVATING HUMAN RESOURCE POLICY

The human resource management approach must motivate the employees to take a customer-focused and service-oriented approach when pursuing their tasks. This includes:

• Hiring policies which encourage service-oriented persons to apply.

• Job descriptions which encourage a service orientation and customer focus.

• Career plans that encourage a service orientation and customer focus.

• Reward systems that appreciate service-orientation and customer-focused behaviour.

These aspects of human resource management aim at supporting a service culture and an interest in internal and external customers. If they are mismanaged, the culture will not enable a service orientation and an interest in customers, which are prerequisites for successful interactive marketing and customer-focused part-time marketer behaviour.

It is essential to hire and keep the right kind of employees in a firm. Successful internal marketing starts with recruitment and hiring. This, in turn, requires proper job descriptions where the part-time marketer tasks of contact and support employees are recognized. Job descriptions, recruitment procedures, career planning, salary, bonus systems and incentive programmes, as well as other HRM tools, should be used by the organization to pursue internal marketing goals.

FIGURE 14.2

Strategic internal marketing: motivating human resource policy.

None of the HRM-related tasks is new. However, they are often used passively, more like administrative procedures than as active marketing tools to achieve internal objectives. The external marketing implications of these tasks are also all too often neglected. Because of the traditional management approach, most employees are considered costs only, and not revenue-generating resources, and the human resource policy is developed accordingly.

Rewarding employees for good service is also an important internal marketing instrument.22 People should know that good service is appreciated by the firm and this should be recognized in the reward system. Far too often cost-efficiency achievements and other internal efficiency factors are the basis for reward systems. If a high number of phone calls dealt with is considered good and rewarded in spite of the fact that customers may be dissatisfied because they feel that they received too little attention, good service is not encouraged.

In many service businesses, the important customer contact jobs are placed in the hands of the newest, least-trained employees, who are often hired on a part-time basis only. Quite often they are unskilled and paid little. Their job can be monotonous. No positive relationships with the employer can develop under such circumstances, although such employees can have a major influence on customer experiences of service quality. Their impact on profits can be equally important.23

Key aspects of motivating human resource policy as part of strategic internal marketing are summarized in Figure 14.2.

MOTIVATING TRAINING POLICY

Educating employees and training programmes are part of human resource management. However, because of the central importance of training for successful internal marketing, training policies and programmes are discussed in a separate section. Training is the most frequently used internal marketing activity, and it is almost always required. However, the training policy is of strategic importance. Strategically, it has to be geared towards the creation and maintenance of a service culture, which enables and reinforces service-mindedness and a customer focus within the organization. A lack of understanding of the firm’s strategies and of the importance of part-time marketers’ responsibilities is almost always present. ‘Service knowledge’ and adequate skills are lacking. This is partly due to insufficient or non-existent knowledge of the meaning of a service strategy, of the nature and scope of marketing in a service and relationship context, and of the employees’ role with dual responsibilities in the firm. This often goes for managers on all levels as well as for contact and support employees.

Partly, this is an attitude problem. Indifferent or negative attitudes have to be changed. On the other hand, attitude problems normally follow on from a lack of understanding of facts and a lack of adequate skills. Therefore, the tasks of improving employees’ knowledge and changing attitudes are intertwined.

Training, either internal or external, is most frequently needed as a basic component of an internal marketing process. Three types of training tasks can be included:

Developing a holistic view of a service strategy and of the total customer management or marketing process, as well as of the role of each individual in relation to other individuals and processes in the firm, and in relation to customers.

Developing adequate technical knowledge and skills about how to provide good service and how to handle customer contact situations.

Developing and enhancing favourable attitudes towards a service strategy, a customer focus and part-time marketer performance.

Developing and enhancing communications, sales and service skills among employees.

Training, together with internal communication support, are the predominant tools of the communications management aspect of internal marketing. However, at the same time they are also part of the attitude management process. If the first type of training goal is overlooked, it will be very difficult or impossible to create conditions for favourable attitudes towards service and part-time marketing responsibilities, or to make employees interested in acquiring the skills required to perform as good part-time marketers. An individual who does not recognize and appreciate the whole picture will not understand why he should change his behaviour towards fellow employees and customers and bother to acquire new skills unrelated to his traditional tasks. Because employees need to feel that there is a trusting relationship between fellow employees and management as well as customers, training programmes must also include elements focusing on the fair treatment of both employees and customers.24

Key aspects of motivating training policy as part of strategic internal marketing are summarized in Figure 14.3.

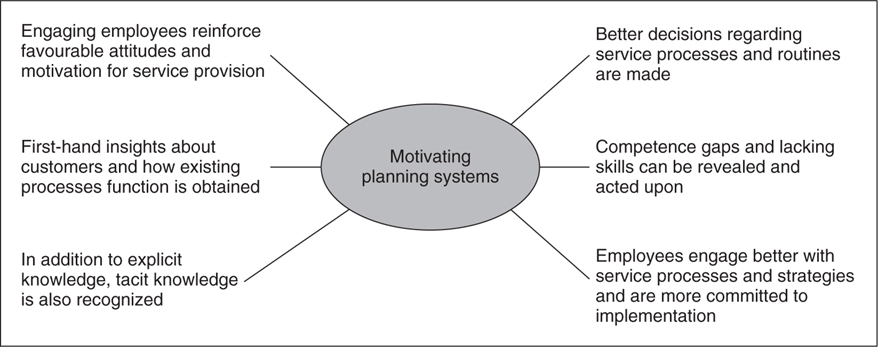

MOTIVATING PLANNING SYSTEMS

Often employees feel frustrated because they cannot influence how work routines and processes are developed. They know from experience and firsthand customer feedback what could be improved. Therefore, employees on many levels in an organization should be actively involved in the planning of their work environment and job routines. The employees have knowledge and insights which are often valuable for planning their jobs. Of course, suggestions based on such knowledge must be evaluated in accordance with the firm’s strategy. In a later section, a relationship-mediated model of internal marketing relying on a motivating planning system will be described.

Firms seldom make use of the firsthand knowledge of customer processes, needs and expectations held by customer contact employees. As a consequence, actions needed to correct or improve service processes and employee skills are not taken, or processes and skills are developed in a less than optimal way, sometimes in a counterproductive direction. This is also true in the case of internal processes, where the insights of support employees go unnoticed.

FIGURE 14.3

Strategic internal marketing: motivating training policy.

Including employees in planning processes has at least the following benefits:

• Knowledge of how service processes function and problems with practical implementation, and about opportunities to improve them, is used.

• Knowledge about internal and external customers’ views of existing processes and how such processes could be improved is used.

• Tacit knowledge as well as explicit knowledge is recognized and can be used.

• Employees who have been actively involved in planning and development processes easily feel more committed to executing new plans than other employees.

From an internal marketing perspective, the main reason to include employees in planning processes is to create and reinforce customer-centric and service-oriented attitudes in the organization. However, at the same time, better insights into how existing processes work (and why they sometimes do not work well) and knowledge about the firm’s customers are obtained to improve existing processes. These insights exist in the form of tacit knowledge, which is made explicit only by deliberate actions. Furthermore, employees who have been engaged with planning processes which they are part of can be expected to commit themselves to implementing these processes more wholeheartedly than otherwise.

Engaging employees with planning processes can of course be done in many ways, both through formal routines and in informal ways. Whenever possible formal planning routines can be used, but informal contacts between a manager or supervisor and contact employees may often both enhance motivation for good service and reveal useful insights about customers and how service processes function and could be improved.

Key aspects of motivating planning processes as part of strategic internal marketing are summarized in Figure 14.4.

FIGURE 14.4

Strategic internal marketing: motivating planning systems.

INTERNAL MARKETING ACTIVITIES ON THE TACTICAL LEVEL

There is no exclusive list of activities that should belong to an internal marketing process. Almost any activity that has an impact on internal relationships and on the service-mindedness and customer focus of employees can be included.

Typical internal marketing activities can be identified, however. The following list is not intended to be inclusive, nor does it distinguish between activities to be used in developing or maintaining a service culture or in introducing new goods, services and marketing campaigns internally. Many of the activities are common to two or three of these situations.

TRAINING

As mentioned above, training is the most frequently used tactical internal marketing activity, and is almost always needed. However, it is important to remember that training is seldom enough to achieve lasting, or even short-term, results. Training must always be supported by other actions, out of which leadership and management support are most important. Training was discussed extensively in the context of strategic internal marketing, and will therefore not be discussed here any further.

INTERNAL MASS COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION SUPPORT

Most managers and supervisors realize that there is a need for them to inform employees about new service-oriented strategies and new ways of performing in internal and external service encounters, and to make them understand and accept new strategies, tasks and ways of thinking. However, many people do not know how to do this. Therefore, it is important to develop various kinds of support materials. Computer software, PowerPoint presentations and other audio-visual and written material explaining new strategies and ways of performing can easily be used by managers during staff meetings.

Brochures, internal memos and magazines, as well as other means of mass-distributed communications material, can of course also be used in internal marketing.

HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

HRM activities are also part of an internal marketing process. However, such tasks were discussed in the section on a motivating human resource policy and will therefore not be discussed any further here.

EXTERNAL MASS COMMUNICATION

The internal effects of any external mass communication are seldom fully recognized. However, employees almost always form an interested and responsive target audience for advertising and other marketing communication campaigns. Such activities and campaigns, and the customer promise inherent in them, should be presented to employees before they are launched externally. This may create commitment and decrease confusion. One step further would be to develop such campaigns in co-operation with the employee groups affected by the external communication effort. This can be expected to commit employees to the fulfilment of promises made in planned external marketing communication.

DEVELOPING SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY SUPPORT

The development of customer information databases, systems for effective internal service support, and other types of systems and technologies that make it possible for the contact employees to provide good service are important parts of internal marketing. If such support is lacking, even the most customer-focused and service-minded employees will eventually start to feel frustrated and lose interest in being good part-time marketers.

Information technology and the development of intranets have had a tremendous impact on internal processes and provided an effective support system in internal marketing. Through easy access to databases, websites and e-mail, and also social media, people and internal processes can reliably and quickly connect to each other. The feeling of being connected to the same body of information as everyone else may create a commitment to a mutual cause among employees, which has a positive influence on internal relationships.25 However, there is also a risk that the use of e-mail and intranets may alienate employees from each other and from the work community. It is too easy to be antisocial and only communicate using information technology. Such negative aspects of this technology are also enhanced by a surplus of information, much of which may be totally irrelevant.26

INTERNAL SERVICE RECOVERY

From time to time customer contact employees and support employees face service encounters where a service failure has occurred, or have to interact with customers who are having a bad day. The situation may be frustrating and sometimes also humiliating for the contact person. Furthermore, the less empowered they are, the more they may experience feelings of low perceived control of the tricky situation and helplessness in dealing with the service failure. The customers may have been emotionally upset, frustrated or angry. Internal customers may react in similar ways. Contact persons who have had to cope with situations like these may need help to recover from the mental stress they suffer following such encounters and from the pressure that they have been under. The firm must actively address these issues to help employees to recover. Bowen and Johnston call this internal service recovery.27 Managers and supervisors have a decisive role in handling such internal recovery situations. Support from the whole work group can be valuable for fellow employees in such stressful circumstances. Management may need to a create a system which guarantees that a support network exists and functions.

MARKET RESEARCH AND MARKET SEGMENTATION

Both internally and externally, market research can be used to find out, for example, attitudes towards part-time marketing tasks and service-oriented performance. Market segmentation can be applied in order to find the right kind of people to recruit for various positions in the organization.

In Table 14.2 internal marketing activities are summarized.

Internal marketing activities.

Training • Target groups: employees on all levels from top management to middle management, supervisors and support and contact personnel. • Understanding of the employees’ role in the total relationship with a customer and of each and everyone’s role and tasks in maintaining and enhancing this relationship. • Interaction and communication skills. Leadership and management/supervisory support • Leadership and management/supervisory support is a continuation of training sessions, which either brings the messages of such sessions alive or kills them. • Top management must personally demonstrate customer-focused and service-oriented attitudes and behave accordingly. • Every manager/supervisor must live up to customer- and service-focused standards. • They must support and not counteract the motivation of and possibilities for their people to perform in a customer-oriented and service-focused manner. Internal communication and dialogue • No memos must be used. • As little one-way information as possible. • As much personal contact as possible. • As much dialogue as possible. • Use intranets for key information. • E-mail can be used, but avoid overload and if appropriate enable e-mail response. Make use of internal effects of external communication • The employees are always an eager audience for external communication. • Emphasize the role of your employees in advertising and in other external campaigns. Involve your employees in planning • Your employees are a source of tacit knowledge about customer preferences and customers’ everyday activities, expectations and requirements. • Involvement has a motivating effect. • The marketing communication effort that is developed can be better than it would have been otherwise. Reward your employees for successful performance • Encourage employees, show respect for them and acknowledge good performance. • Correct mistakes and give advice for the future in a positive and encouraging manner. • Although encouragement and job satisfaction are good motivators, bonuses and rewards are also supportive. Develop supportive technologies and systems • Make sure that support systems, databases and physical instruments required in the service process are supportive to service-focused and customer-oriented behaviour and performance and do not become a hindrance to such behaviour. Use human resource management instruments • Use HRM activities in an active way that not only helps create job satisfaction and a satisfying work environment, but at the same time directs the interests of employees towards customers and customer-focused behaviour so that they become good part-time marketers. Do internal market research and segmentation • Job satisfaction usually correlates with customer satisfaction. • Study the employees’ attitudes and preferences towards the work environment, their tasks and the challenge of customer-focused and service-oriented behaviour. • Use qualitative as well as quantitative methods; make use of information and feedback from encounters that managers and supervisors have with their team members. • Remember that employees also form a heterogeneous group and therefore may have to be segmented into subgroups that in some respects are approached in different ways. |

A RELATIONSHIP-MEDIATED APPROACH TO INTERNAL MARKETING

In his research David Ballantyne has taken a relationship approach to internal marketing, where he views it as knowledge renewal.28 Groups of customer contact employees have accumulated knowledge about customers’ behaviour and preferences as well as about how, and with what means, to best serve customers and create a good service quality perception. However, this knowledge has the form of tacit knowledge, which is not documented in formal procedures or even known to management. And it is probably not known to everyone who serves customers and perhaps not widely used in the organization. This knowledge may be actively used or, if restricted by company policies, reward systems or supervisory control, not used other than marginally or not at all. If that is the case, it probably frustrates the employees and has a negative impact on their service orientation and customer consciousness. According to Ballantyne, this tacit knowledge has to be interpreted and codified, and if found useful as explicit knowledge circulated in the organization for use by everyone serving internal or external customers. If based on strategy and cost–benefit considerations found appropriate, this tacit knowledge made explicit could change company policies. In the best case scenario the new explicit and authorized knowledge about how to serve customers becomes part of the corporate culture and as tacit knowledge steers the employees’ attitudes and behaviours.

According to Ballantyne, this process of knowledge renewal has four stages.

Energizing: revealing common knowledge by exploring tacit knowledge.

Code breaking: discovering new knowledge by turning tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge.

Authorizing: making cost–benefit and policy considerations and transforming tacit-made-explicit knowledge into explicit knowledge that from a strategic and commercial perspective can be put to use.

Diffusing: integrating the new explicit knowledge with corporate culture and behaviour by disseminating the new explicit knowledge in the organization.

In the first phase of the process, the energizing phase, groups of employees are gathered to discuss customer service and various means of servicing customers as well as obstacles and challenges related to this. Such obstacles can be related to anything, for example, existing skills, IT and physical support, atmosphere, company policies, reward systems and supervisory control. The groups are given the opportunity to meet regularly and discuss freely. This first energizing phase should not necessarily lead to any conclusions or suggestions yet. At the same time as tacit knowledge held by the participants is explored it is a socialization process where the participants should create a willingness to pass on to other group members the knowledge and experiences they have gathered in their job. A mutual trust among the participants should develop, otherwise discussions and knowledge transfers will be constrained.

In this and the next phase of the process discussions, role play and group-based dialogue could be used. Of course, any other way of comparing experiences and making knowledge and thoughts explicit could also be used.

After the initial phase the code breaking phase follows. There, when the group members have already familiarized themselves with other participants and developed a trust in each other, the main task is to discover knowledge that, based on their experience, the members have gained and perhaps made use of. Old codes should be broken and new opportunities explored. In this way the tacit knowledge held by the group members is turned into explicit knowledge. As the participants know that their task is to develop new ways of serving customers (or of performing any task), a mutual obligation to drive the task through should keep the process going.

In the authorization phase the developments and suggestions created in a group are analysed from a company policy and cost–benefit point of view. This analytical task can to some degree be done in the group, but other than in special cases, the final analysis and decisions have to be made on a management level. This is, of course, due to the fact that company strategies, budget restrictions and other management considerations have to be taken into account. This is a process where tacit-made-explicit knowledge about service procedures and cost–benefit and policy considerations are brought together. Through this process, explicit knowledge created by the groups is further developed into new procedures and routines to be used in the organization. It is probable that some developments and suggestions by the group cannot be transformed into new procedures. This can be due to, for example, cost–benefit considerations and company strategies or policies that would be violated, and according to management should not be changed.

In the final stage of the process, the diffusing phase, the new authorized knowledge is integrated with corporate culture through, for example, new designs, support systems and procedures as well as training programmes and new supervisory methods and leadership. The goal is not only to make the new knowledge and the changes in the organization known to everyone concerned, but also to achieve personal commitment by the employees. In this way the new explicit knowledge is transformed back into tacit knowledge that consciously and unconsciously steers the behaviours of the employees in the organization. It is integrated with and reinforces the company culture and in some cases even alters it.

Input to this internal marketing process is the personal knowledge of employees, possibly supported by market intelligence. The output can be expected to be a higher level of customer consciousness in the organization and, as a consequence, improved customer-perceived service and relationship quality as well as enhanced market performance of the firm.29

EMPOWERING AND ENABLING EMPLOYEES

Two concepts that are closely related to internal marketing are empowering and enabling. An understanding of both concepts and their meaning is important for the effective implementation of internal marketing.

Empowering employees means to give people in an organization, some of whom are customer contact employees, the authority to make decisions and take action in a large number of potentially problematic situations.30 The main reason for empowerment is the employee motivation effect that can be achieved.31 There will probably be limits on how far this authority can go, and these limits must be carefully determined. For example, decisions where legal matters have to be considered and/or large sums of money are at stake probably need to be taken to a higher management level. Management must set clear and acceptable boundaries for frontline employees’ service recovery latitude.32 The main thing is that the contact (or support) employee knows his responsibilities and is encouraged to perform more effectively and in a more customer-focused fashion. The ultimate goal is, of course, to improve the part-time marketing performance of the customer contact and support employees.

Correctly implemented empowerment as part of an internal marketing process can have a decisive impact on the job satisfaction of employees, which in turn may improve the part-time marketing impact of employees in customer contacts. Through improved customer retention and more cross-sales this can be expected to have a positive effect on profit.33

The empowerment concept has, however, also been criticized. It has been claimed that little real empowerment take place,34 and that change programmes which aim at empowering employees are full of inner contradictions that have a negative impact on motivation. Managers consciously and unconsciously by their actions and attitudes counteract efforts to empower personnel. In practice they rely more on standardized processes that steer the performance of the employees in a predetermined direction. This does not create an environment for self-governance or for motivated employees to take responsibility for their actions, especially for actions that deviate from the normal route.

However, if empowerment is successfully introduced, the results can be good. Empowerment demands a continuous nurturing of trusting relationships between management and employees.35 Managers must show that they respect employees’ authority to analyse situations and make decisions. In this way a mutual trust between management and employees can be instilled. It is also important to realize that empowerment cannot happen overnight. Rather, management must create and maintain the conditions needed so that an employee can feel that he has power and can use his power in customer interactions.36 The enabling concept is part of the process of creating the conditions required for empowerment.

Bowen and Lawler37 put empowerment in a larger context. They claim that empowering employees means (1) providing them with information about the performance of the organization, (2) rewarding them based on the organization’s performance, (3) creating a knowledge base that makes it possible for employees to understand and contribute to the performance of the organization, and (4) giving employees the power to make decisions that influence organizational directions and performance.

Empowerment cannot function without simultaneously enabling employees so that they are prepared to take the responsibility that goes with the new authority. Much of the concern about empowerment in the literature seems to be due to lack of enabling. The employees must understand what goals they should be aiming at by making empowered decisions, and feel that they have the capacity and knowledge required for such behaviour. Enabling means that employees need support to be able to make the independent decisions effectively in the service process. Without such support, proper conditions for empowered employees do not exist. Enabling includes:

Management support, so that supervisors and managers give information and also take over decision-making when needed but do not interfere unnecessarily with the decision-making authority given to employees.

Knowledge support, so that employees have the skills and knowledge to analyse situations and make proper decisions.

Technical support, from back-office support staff, systems, technology and databases that provide contact employees with information and other services and tools required for handling a wide variety situations.

It is important to realize that empowerment without enabling creates more confusion and frustration than job satisfaction and motivation among employees. People who are required to take responsibility for customers but who are not enabled to do so will feel confusion, frustration and anger, and they will probably make bad decisions. The connections between empowerment and internal marketing can easily be seen. Among the objectives of internal marketing is the development of management support, knowledge support and technical support so that empowered employees have the tools and assistance they require and will feel motivated to perform effectively as part-time marketers.

The benefits of empowerment of service employees are as follows:38

Quicker and more direct response to customer needs in the service process, because customers will not have to wait for a decision until a supervisor can be found in unusual situations. At the same time, customers will experience a feeling of spontaneity and willingness to help which has a positive effect on perceived service quality.

Quicker and more direct response to dissatisfied customers in service recovery situations, again because customers will not have to wait for a decision until a superior can be found, or will not have to file a formal complaint in situations that do not warrant such a complicated procedure.

Employees are more satisfied with their job and feel better about themselves, because they take ownership of their job and know that they are trusted employees. This may also decrease absenteeism and employee turnover.

Employees will treat customers more enthusiastically, because they are more motivated to do their job. This of course requires that they have been made aware of their part-time marketing responsibilities.

Empowered employees can be a valuable source of new ideas, because they have direct customer contacts, see the problems and opportunities experienced in service encounters, and the customers’ behaviours, needs, wishes, expectations and values. As empowered employees they are more inclined to notice these problems and opportunities and to share the findings and ideas they get from them with supervisors and managers.

Empowered employees are instrumental in creating good word-of-mouth referrals and positive comments in social media, and increasing customer retention, because they can be expected to serve customers in a quick, skilful and service-oriented manner, thus surprising customers and making them more inclined to spread the word and stay with the same service provider.

Empowerment does not mean that managers and supervisors should have less managerial responsibility.39 The nature of this responsibility will change, however: there will be more leadership orientation instead of mere managing, more independent judgement instead of managing by the book, and a clear understanding when decisive action on the part of the manager or supervisor is required.

Sometimes empowering employees may incur some extra costs. Additional employee training may be required and it may be necessary to pay empowered employees better. There is also, of course, the risk that empowered customer contact employees will make bad decisions that may cost the firm money and perhaps also have a negative effect on customers. This can, however, be avoided by recruiting and enabling personnel carefully. It should also be remembered that not all employees can be empowered, because not everyone will want to have the responsibility that goes with it. Some seemingly unnecessary costs that make customers happy, for example, in service recovery situations, will probably pay off in the long run.

AN APPROACH TO MOTIVATING EMPLOYEES

Berry and Parasuraman40 offer a number of guidelines for firms that want to practice internal marketing effectively:

Compete for talented employees.

Offer a vision that brings purpose and meaning to jobs.

Make sure that employees have the skills and knowledge needed to do their job excellently.

Create teams of people who can support each other.

Leverage the freedom factor.

Encourage achievements through measurement and rewards.

Base job design decisions on research.

These seven guidelines make good sense; however, it is not always easy to implement them.41 Employees need to be empowered to perform, but they also need the support of good management, support systems, technology and information. They also need training so that they have the skills needed to perform effectively. Most people feel motivated to perform better if they have the freedom to think, analyse, make decisions and act. To be able to do that they need knowledge and skills, so that they feel secure in an empowered position. It all starts with recruitment procedures. The better people the firm can hire from the outset, the more effectively they will perform as part-time marketers and in their other duties. In spite of all its technology, a firm is only as good as its people. However, how often do firms violate some or all of these guidelines when hiring and managing customer contact employees or support employees and their supervisors and managers?

HOW TO IMPLEMENT AN INTERNAL MARKETING PROCESS

When starting to plan and implement an internal marketing process, a few guidelines should be observed. First of all, the internal focus of internal marketing has to be recognized and fully accepted by management. Employees sense that management considers them important when they are allowed to participate in the process, both in an internal research process and in planning their work environment, the goals and scope of their tasks, information and feedback routines and external campaigns. When employees realize that they are able to involve themselves in improving something that is important to them, they will be more inclined to commit themselves to the business and the goals of the internal marketing strategy.

However, the external focus of an internal marketing strategy process should never be forgotten. Improving the work environment and tasks for the employees is, of course, an important objective in its own right. It is, nevertheless, the external marketing impact of every employee that is the ultimate focus of internal marketing. The ultimate objective is to improve customer consciousness and service mindedness and thus, in the final analysis, the interactive marketing abilities and the part-time marketing performance of the employees. Consequently, the internal and the external focus of internal marketing go hand in hand.

Furthermore, it should always be remembered that if the internal marketing process is viewed as being simply tactical and initiated only at the customer contact level involving only contact employees, it will fail. This level alone cannot breed a service culture for the organization, nor reach the many support employees who also have to function as part-time marketers internally. Only in a situation where a solid service culture has been established can the internal marketing of, for example, an advertising campaign or a new service be directed towards a specific target group of, say, contact employees in a certain department. In all other situations, internal marketing has to involve everyone in the organization, and start with top management and include middle management and supervisors. As has been said, continuous management support, not only by paying lip service to internal marketing, but by active involvement in the process, is an absolute necessity.

Finally, internal marketing is a continuous process. The organization needs constant attention from management. Changes in strategy, in technologies used in service processes and in external marketing must always be carefully introduced to the organization. Changing a corporate culture in a service-oriented direction takes time, and management must understand that it has to be given the time it takes. After that the service culture has to be continuously nurtured.

NOTES

1. The ultimate idea of internal marketing, to make sure that employees make a good impression on a firm’s customers and support customers’ perception of quality, is growing in importance. Internal marketing has been the subject of continuous academic research. For some recent publications where internal marketing is studied in various contexts, see for example Peltier, J.W, Schibrowski, J.A. & Nill, A., A hierarchical model of the internal relationship marketing approach to nurse satisfaction and loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 47(5-6), 2013, 899–916; Ting, S-C., The effect of internal marketing on organizational commitment: job involvement and job satisfaction as mediators. Educational Administration Quarterly, 47(2), 2011, 353–382; and Papasolomou, I., Kountouros H. & Kitchen, P.J., Developing a framework for successful symbiosis of corporate social responsibility, internal marketing and labour law in a European context. The Marketing Review, 12(2), 2012, 109–123.

2. The observation of the existence of an internal market and of the need for service firms to market their campaigns and offerings internally was probably first made by Eiglier and Langeard in France in a working paper published in 1976 (Eiglier, P. & Langeard, E., Principes politique marketing pour les enterprises des services. Working Paper, Institute d’Administration des Enterprises, Université d’Aix-Marseille, December, 1976), although they did not explicitly use the phrase ‘internal marketing’. In the same year Sasser and Arbeit addressed the issue of ‘selling jobs to the employees’ and discuss recruitment, training, motivation, internal communication and retention of service-minded personnel as aspects of this internal task (Sasser, W.E. & Stephen P., Selling jobs in the service sector. Business Horizons, 19(3), 1976, 61–65). In the 1970s, Christian Grönroos also pointed out the need for internal marketing (Grönroos, C., A service-orientated approach to the marketing of services. European Journal of Marketing, 12(8), 1978, 588–601). Leonard Berry was another early proponent of internal marketing (Berry, L.L., The employee as customer. Retail Banking, March, 1981).

3. In some publications on internal marketing the relationship between internal suppliers and internal customers (that is, the marketing of goods and services internally in the organization) is considered the main or only domain of internal marketing. See, for example, Ling, I.N. & Brooks, R.F., Implementing and measuring the effectiveness of internal marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 14, 1998, 325–351 and Reynoso, J.F. & Moores, B., Internal relationships. In Buttle, F. (ed.), Relationship Marketing: Theory and Practice. London: Paul Chapman Publishing, 1996, pp. 55–73. In this book, the authors have a much broader perspective.

4. See, for example, Voima, P., Negative Internal Critical Incident Processes. Windows on Relationship Change. Helsinki: Hanken Swedish School of Economics, Finland, 2001 and Ballantyne, D., A relationship-mediated theory of internal marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 37(9), 2003, 1242–1260.

5. Varey, R.J., Internal marketing: a review of some inter-disciplinary research challenges. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 6(1), 1995, 40–63; Voima, P. & Grönroos, C., Internal marketing – a relationship perspective. In Baker, M.J. (ed.), The IEBM Encyclopedia of Marketing. London: International Thomson Business Press, 1999, pp. 747–751; Gummesson, E., Internal marketing in the light of relationship marketing and virtual organizations. In Lewis, B. & Varey, R.J. (eds), Internal Marketing. London: Routledge, 2000; Voima, P., Internal relationship management – broadening the scope of internal marketing. In Lewis, B. & Varey, R.J. (eds), Internal Marketing. London: Routledge, 2000.

6. Gummesson, op. cit. See also Ballantyne, D., Internal marketing for internal networks. Journal of Marketing Management, 13(5), 1997, 343–366.

7. Cacciatore, L., När företagets och servicepersonalens uppfattning om det riktiga i företagets strategi kolliderar. En studie i användningen av intern marknadsföring för att motivera kontaktpersonalen i en bank i Finland. Helsinki: Hanken School of Economics, Finland, 2014.