CHAPTER 7

MANAGING THE AUGMENTED SERVICE OFFERING

“Customers deserve more than just a good service package. It has to be made into a functioning service process too.”

INTRODUCTION

Based on discussions of service quality in previous chapters, this chapter presents a conceptual model of how to develop service offerings that are geared to customers’ perception of the quality of services. The conceptual model is called the augmented service offering model. It takes into account the impact of the outcome of the service processes (the technical quality of the service) and the impact of how customers perceive the processes (the functional quality of the process). The effects of brand image and marketing communication on the service offering are also discussed. Then, service design and a model of designing for service are presented, and finally a model of service offering development in the marketspace called the NetOffer model is discussed. After having read this chapter the reader should understand the complexity and scope of service as an offering and know how to develop a service offering. The reader should also understand what such an offering includes in a marketspace context. Finally, the reader should understand what designing for service means and what such a process includes.

THE MISSING SERVICE PRODUCT: SERVICES AS A BUNDLE OF OUTCOME- AND PROCESS-RELATED FEATURES

One of the essential cornerstones in developing service management models is a thorough understanding of the phenomenon to be studied. In other words, what is needed is a good model of services as offerings to be produced, marketed and consumed. Physical products are a bundle of features embedded in the ready-made product. However, as discussed in Chapter 2, services are different. Services are processes, where no pre-produced product to be marketed and consumed exists.

To understand service management and how to market services it is important to remember that all models and concepts are based on the fact that the service emerges in a process, in which the customer participates as a co-producer, and that the production of a service is not separated from the consumption of this service. Moreover, this process forms an essential part of the service. From the service provider’s point of view, some of the service is produced in a back office, but from a quality perception perspective the most critical part of the service is produced at the time when the customer participates, perceives and evaluates the service process.

As discussed in previous chapters, instead of product features embedded in a pre-produced physical product, services consist of a bundle of features which are related to the service process and the outcome of that process. Neither of these exists before the customer initiates the service production process. These characteristics of services have to be taken into account when developing models describing services. We name the bundle of process- and outcome-related features a service offering, and the comprehensive model of a service offering described in this chapter is called the augmented service offering model.1

This chapter will not discuss a new service development process from idea generation to launch.2 Instead, it will concentrate on the core of such a process, that is, how to understand and manage the object of development itself, the service offering. Without a thorough understanding of this core concept, every attempt to design and develop service will fail or at least be less effective.

Any attempt to conceptualize the service offering has to be based on a customer perspective. Far too often internal aspects, too little market research information, or too limited understanding of the customers’ point of view guide the process of conceptualizing services to be offered to the market. However, well planned does not automatically mean well executed. The following sections are going to address, in detail, how to develop the service offering so that all aspects are thoroughly covered. This requires, among other things, that service production and delivery issues (that is, the service process) be incorporated as inseparable parts of the process of planning a service offering. Otherwise, well-planned service offerings may remain theoretical, unless the execution of plans is made an integral part of the undertaking to create a service offering.

THE SERVICE PACKAGE

According to the service package model, which is often used in the literature, the service is described as a package or bundle of different services, tangibles and intangibles, which together form the service.3 The package is divided into two main categories: the main service or core service and auxiliary services or extras, which are sometimes referred to as peripherals or peripheral services, sometimes also as facilitator services. A hotel service may include the accommodation element as the main or core service, and reception service, valet service, room service, restaurant services and the concierge as auxiliary services or peripherals in the package. Such extras are often considered to be the elements of the service package that define it and make it competitive.4

Lovelock developed a model of the service offering which includes supplementary services in addition to a core service. Supplementary services resemble the idea of auxiliary services and extras.5 This is a simple and realistic way of illustrating at least part of the nature of any service. However, it has a few weaknesses if it is to be used for managerial purposes. First, a service is more complicated than this model would suggest. From a managerial perspective auxiliary or supplementary services may be used for totally different reasons. This has to be recognized. Second, the main service/auxiliary service (core service/peripherals, supplementary) dichotomy is not clearly geared to the customer perception of a service and total service quality. Only what is supposed to be done for customers is recognized.

How the service process and the process-related features are to be handled (i.e. the functional quality aspects of a service) is not included.

A model of the service offering has to be customer-centric. It has to recognize all the aspects of a service that are perceived by customers. How customers perceive the interactions with the service provider (the functional quality of the service process) as well as what the customers receive (the technical quality of the outcome) has to be taken into account. In addition to this, the image impact on service quality perception also has to be recognized. What has to be planned and marketed and offered to customers is a comprehensive service offering.

MANAGING THE SERVICE OFFERING

Based on a thorough understanding of the customers’ everyday activities and processes a well-defined customer benefit concept, which states the benefits or bundle of benefits customers appreciate, can be derived. Having gained this knowledge about target customers the firm can develop and manage service offerings. Managing a service offering requires four steps:

Developing the service concept.

Developing a basic service package.

Developing an augmented service offering.

Managing image and communication.

The service concept or concepts determine the intentions of the organization. The package can be developed based on this concept.

The basic service package describes the bundle of services that are needed to fulfil the needs of customers in target markets. This package, then, determines what customers receive from the organization. A well-developed basic package guarantees that necessary outcome-related features are included, and that the technical quality of the outcome will be good. However, even an excellent service package can be destroyed by the way in which the service process functions. Therefore, a good service package does not necessarily mean that the perceived service is good, or even acceptable. According to the quality models of services, the service production and delivery process, especially the customer perception of the buyer–seller interactions or the service encounter, is an integral part of the service. This is the reason why the basic service package has to be expanded into an augmented service offering before we have a description of the service as an offering.

In the augmented service offering model the service process and the interactions between the organization and its customers as well as customers’ co-production efforts are included. In this way the model of the service offering is geared to the total customer perceived quality of services.

Finally, image has a filtering effect on the quality perception. Therefore, the firm has to manage its corporate and/or local image and its marketing communication so that they enhance the perception of the augmented service offering.

THE BASIC SERVICE PACKAGE

As noted previously, in the literature a distinction is often made between core services and supplementary/auxiliary/peripheral services. However, for managerial reasons, it is useful to distinguish between three groups of services:6

Core service.

Enabling services (and goods).

Enhancing services (and goods).

The core service is the reason for a company being on the market. For a hotel it is lodging and for an airline it is transportation. A firm may also have many core services. For example, an airline may offer shuttle services as well as long-distance transportation. A mobile phone operator may, for example, offer phone calls as well as an e-mail facility as its core services.

In order to make it possible for customers to use the core service some additional services are often required. Reception services are needed in a hotel, and check-in services are required for air transportation. Such additional services are called enabling or facilitating services, because they enable the use of the core service.7 If enabling services are lacking, the core service cannot be consumed. Sometimes enabling goods are also required. For example, in order to be able to operate an automatic teller machine, a customer needs a bank card. However, it is often difficult to say whether the physical things involved in the service offering are goods given to the customer as part of the service production process or are physical production resources. For instance, the bank card can be considered a physical thing (an enabling physical good), but it can equally be considered a production resource. The ATM equipment, on the other hand, is definitely a physical production resource and not an enabling good.

The third type of service is enhancing or supporting services. These, like enabling services, are also auxiliary services, but they fulfil another function. Enhancing services do not facilitate the consumption or use of the core service, but are used to increase the value of the service and/or to differentiate the service from that of competitors. Hotel restaurants and airport lounges and a range of in-flight services related to air transportation are examples of enhancing services. Games and wake-up calls are examples of enhancing services offered by a mobile phone operator. In some cases physical things that can be considered enhancing goods are used to enhance the service offering. Shampoo and shoeshine in hotel rooms are such goods.

The distinction between enabling services and enhancing services is not always clear. A service that in one situation is enabling the core service – for example, an in-flight meal on a long-distance route – may become an enhancing service in another context, i.e. on a short flight.

From a managerial point of view it is important to make a distinction between enabling and enhancing services. Enabling services are mandatory. If they are left out, the service package collapses. This does not mean that such services could not be designed in such a way that they differ from the enabling services of the competitors. On the contrary, whenever possible enabling services should be designed so that they also become means of competition and thus help to differentiate the service. Enhancing services, however, are used as a means of competition only. If they are lacking, the core service can still be used. However, the total service package may be less attractive and perhaps less competitive without them.

The basic service package is, however, not equivalent to the service offering customers perceive. This package corresponds mainly to the technical outcome dimension of the total perceived quality. The elements of this package determine what customers receive. They do not say anything about how the process is perceived, which in the final analysis is an integral part of the total service offering customers experience and evaluate. In other words, no process-related features of the service have yet been taken into account.

As the perception of the service process cannot be separated from the perception of the elements of the basic service package, the process has to be integrated into the service offering. Therefore, the basic service package has to be expanded into a more comprehensive model, called the augmented service offering model.

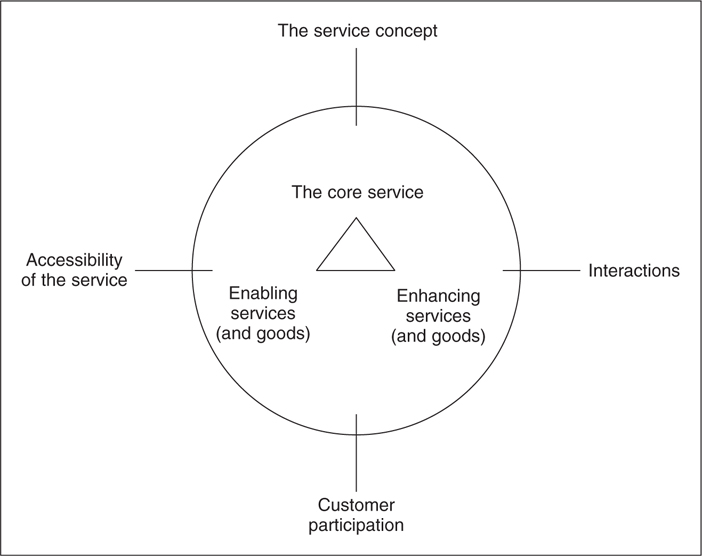

THE AUGMENTED SERVICE OFFERING

The service process, the buyer–seller interactions or service encounters, are perceived in a number of ways, which differ from situation to situation. Due to the characteristics of most services, there are, however, three basic elements, which from a managerial point of view constitute the process:8

Accessibility of the service.

Interaction with the service organization.

Customer participation.

These elements are combined with the concepts of the basic package, thus forming an augmented service offering (see Figure 7.1). It is, of course, essential that these three elements of the service offering are geared to the customer benefits that were initially identified to be sought by customers in the selected target segments, and the service concept based on these benefits.

FIGURE 7.1

The augmented service offering.

Source: Developed from Grönroos, C., Developing the service offering – a source of competitive advantage. In Surprenant, C. (ed.), Add Value to Your Service. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association, 1987, p. 83. Reproduced by permission of the American Marketing Association.

The accessibility of the service depends, among other things, on:

• The number and skills of the personnel.

• Office hours, timetables and the time used to perform various tasks.

• Location of offices, workshops, service outlets, etc.

• Exterior and interior of offices, workshops and other service outlets.

• Tools, equipment, documents, etc.

• Information technology enabling customers to gain access to the service provider and the service process, and to use the service.

• The number and knowledge of consumers simultaneously involved in the process.

Depending on these and other factors customers will feel that it is easy, or difficult, to get access to the services and to purchase and use them. If the telephone receptionist of a repair firm lets the customer wait before answering the telephone, or if he cannot find a service technician for the customer to talk to, there is no accessibility to the service. Even an excellent service package can be destroyed in this way. Even if the service package does not totally deteriorate, the perception of the service may be seriously damaged. Internet sites, help desks and call and contact centres are increasingly becoming accessibility issues for service providers.

For example, in a study of a for-profit laboratory in the southwest United States, the accessibility issue could be broken down into four parts: site accessibility, customer ease of use of the physical resources of the laboratory, contact personnel’s contribution to accessibility, and ease of customer participation. The following variables were identified for each of the four aspects of accessibility:

Site accessibility

• The convenience and ease of access from a major street.

• The amount of parking available adjacent to the facility.

• The number of medical facilities located nearby.

• The relative ease of locating the laboratory inside the building.

• Office hours.

• The ease of getting an appointment.

• The size of the waiting room.

Customer ease of use of the physical resources

• The attractiveness and condition of the exterior and interior of the medical building where the laboratory is located.

• The exterior of the laboratory facility.

• The waiting room.

• The patient rooms.

• The restrooms.

Service employees’ contribution to accessibility

• The response time to phone calls.

• The number of employees.

• The skills of employees.

• The response time to people walking in the front door.

• The response time to patients in the waiting room.

• The professionalism of the employees.

• The care taken to reduce unpleasantness of drawing blood.

• The billing procedures.

• The types of payment accepted.

• The insurance arrangements available.

Ease of customer participation

• The number and difficulty of forms to fill out.

• The instructions given to patients concerning procedures the patient must participate in or do alone.

• The difficulty of these procedures.

Interaction with the service organization can be divided into the following categories:

• Interactive communication between employees and customers, which in turn depends on the behaviour of the employees, on what they say and do, and how they say and do it.

• Interactions with various physical and technical resources of the organization, such as vending machines, computers, documents, waiting room facilities, tools and equipment needed in the service production process, etc.

• Interactions with systems, such as waiting systems, seating systems, billing systems, Internet sites and telecommunication systems, systems for deliveries, maintenance and repair work, making appointments, handling claims, etc.

• Interactions with other customers simultaneously involved in the process.

Customers have to get in touch with employees, they have to adjust to operative and administrative systems and routines of the organization, they may have to use websites, and they sometimes have to use technical resources such as teller machines or vending machines. Moreover, they may get in contact with other customers. All these interactions with human as well as physical resources and systems are part of the service perception. Again, if these interactions are considered unnecessarily complicated or unfriendly, the perceived quality of an excellent basic service package may be low.

In the same study interactions between the organization and its customers were broken down into the following parts:

• Interactions with medical personnel (their attitudes, attention to the customer, skill in drawing blood).

• Interactions with customer service department (attitudes, phone answering promptness, prompt and accurate answers to questions).

• Interactions with waiting room environment (space, cleanliness, crowdedness).

• Interactions with other customers (communication between patients).

• Interactions with payment or billing system (means of payment available to choose from, understandability of invoices and receipts).

• Interactions with scheduling systems (waiting time for service).

• Interactions between physicians (referring patients to the laboratory) and customer service department (attitudes, phone answering promptness, prompt and accurate answers to questions, calling results, follow-up).

Customer participation means that the customer has an impact on the service he perceives. Thus, he becomes a co-producer of the service and therefore also a co-creator of value for himself.9 Often the customer is expected to fill in documents, give information, use websites, operate vending machines, and so on. Depending on how well the customer is prepared and willing to do this, he will improve the service or vice versa. For example, if a patient is unable to give correct information about his problems, the physician will not be able to make a correct diagnosis. The treatment may, therefore, be inappropriate or less effective than otherwise. The service rendered by the physician is thus impaired.

In the study the following questions were asked, to identify aspects of customer participation:

• Are patients knowledgeable enough to identify their need or problem?

• Do patients have a reasonable understanding of the time constraints involved?

• Is the patient willing to co-operate in the process?

• Can additional information be obtained quickly from physicians?

In the case of self-service, customers are required to take a more substantial and active co-producer role, using the systems and resources provided by the service firm.

Thus, in service encounters the core service, enabling services and enhancing services of the basic service package are perceived in various ways, depending on the accessibility of the services, how easily and well the interactions are perceived, and how well customers understand their role in the service production process.

Finally, in Figure 7.1, the service concept is seen as an umbrella concept, to guide development of the components of the augmented service offering. The service concept should thus state what kind of core, enabling and enhancing services are to be used, how the basic package could be made accessible, how interactions are to be developed, and how customers should be prepared to participate in the process.

The service concept should also be used as a guideline when, in the next phase of the planning process, adequate production resources are identified. In a going concern there are, of course, a set of human and physical resources as well as functioning systems already in place. They determine to some extent which resources are going to be used. However, the development of an augmented service offering requires a fresh analysis of the types of resources that are needed. Otherwise, existing resources may unnecessarily restrict the implementation of a new service offering. Existing resources must never become a hindrance to the successful implementation of new ideas.

In summary, developing the service offering is a highly integrated process. A new enhancing service cannot be added without taking into account the accessibility, interaction and customer participation aspects of that service. On the other hand, the well-planned introduction of an additional enhancing service, or an improved facilitating service, may become a powerful source of competitive advantage.

MANAGING IMAGE AND COMMUNICATION AND THE SERVICE OFFERING

As illustrated by the model of perceived service quality, image has an impact as a filter on the service experienced. A favourable image enhances the experience; a bad one may destroy it. Therefore, managing image and communication becomes an integral part of developing the service offering.10 Because of the intangible nature of services, marketing communication activities not only have a communicative impact on customer expectations, but a direct effect on experiences as well. This latter effect is sometimes of minor, sometimes of major, importance.

In the long run, marketing communications such as advertising, websites, sales and public relations enhance and to some extent form images. However, even an advertisement or a brochure (which a customer notices and perceives at the point and time of consumption, or in advance) may have some impact on his quality perception of a service. Moreover, word of mouth is essential in this context. Peer communication between customers at the point and time of purchasing and consumption may have a substantial immediate effect as well as a long-term impact. In the same way, a negative comment from a fellow customer may easily change a given person’s perception of the service he receives.

THE ROLE OF TECHNOLOGY IN SERVICE OFFERINGS

The development of information technology and the increase in Internet and mobile technology use has offered new opportunities for firms to develop their service offerings.11 IT systems and improved databases from which customer information files are easier to retrieve, and which are less complicated to update than before, provide customer contact employees with improved support to help them to be customer-centric in interactions with customers. More accurate, easily retrievable and available information about customers enables employees to increase the quality of customer interactions. In addition, this use of technology also has a positive effect on the accessibility of services. The Internet may also improve employees’ ability to handle customer contacts, for example, when routine interactions can be transferred to an Internet-based help desk.

New technology also gives customers the means to access the services of a manufacturer or service firm more quickly and easily. For example, using the website of a manufacturer, a customer can easily request supportive information about how to handle a problem with a production machine or make arrangements for the maintenance of the machine. The Internet and mobile technologies offer lots of opportunities to make a service more accessible than before, and it may also improve interactions. Of course, customers need to be trained and motivated to use a website for such purposes.

However, although some services, such as the purchase of movie theatre tickets, can be completed on the Internet, in most cases the customer will at some point also interact with employees and more traditional physical resources and technologies of the service provider. It should be kept in mind that well-functioning IT and Internet and mobile service interactions have to be supported by the ‘real’, personal interactions that also take place. Quick and easy arrangements to get a maintenance task done using the Internet have to be followed by prompt, skilful and attentive service, otherwise the high-quality perception of the service provider’s use of new technology in the mind of a customer is destroyed by a low-quality perception created by traditional means of producing the service offering.

Finally, one should remember that new technologies used in service processes may not be accepted and appreciated by all customers of a given service provider. Some customers can be motivated to accept new technologies, for example after having been informed about their benefits or after having been trained to use them. Others may want to continue to use more traditional means of interacting with the service provider. In any case, the firm has to introduce new technologies carefully, otherwise their effect may be negative. Also, it is important to market new technologies internally, so that employees are motivated to use them. Employees too have to be properly informed and trained.

DEVELOPING THE SERVICE OFFERING: A DYNAMIC MODEL

The composition of the augmented service offering in Figure 7.1 is static. The model simply lays out the elements that have to be taken into account and introduces appropriate concepts. In this section the model of the augmented service offering will be placed in a dynamic framework, which illustrates more realistically how the service as a product emerges. Because services are processes in which consumption is inseparable from production and delivery processes, the service offering by definition is dynamic. The service exists as long as the production process goes on. Hence, any model of services, such as the augmented service offering, has to include a dynamic aspect.

The framework can be divided into eight steps:

Analysing target customers’ everyday activities and processes.

Assessing customer benefits required to support these activities and processes.

Defining overall features of an augmented service offering.

Defining a service concept which guides the development of the service offering.

Developing the core service, enabling and enhancing services, and goods of the basic service package.

Planning the accessibility, interaction and customer participation elements of the augmented service offering.

Planning supportive marketing communication.

Preparing the organization for producing the desired customer benefits in the service processes (internal marketing).

First, one has to analyse the customers’ everyday activities and processes where they may benefit from a service that the firm can provide them with or develop for them. For example, Apple’s launch of the iPhone was a result of thorough ethnographic studies of what people in large customer segments were doing and would like to do, for example with the support of a new kind of mobile device, combined with the firm’s innovative knowledge of the possibilities of software technology. Then, an assessment of the customer benefits is needed, so that the development process is geared to customer experiences of total service quality. Next, the desired features of a competitive augmented service offering have to be defined as the basis of further planning. These features, following the model of Figure 7.1, should be related to the service concept, and structured according to the elements of the service package and the augmentation elements, as well as related to corporate and local image and market communication.

The next step is to plan the basic package, including the core service, enabling services and goods, and enhancing services and goods, according to the service concept. Then, the augmented service offering – which materializes through the service process – has to be developed, so that the service is made accessible in a way that reflects the service concept, and interactions and customer participation meeting the same criterion emerge.

The next step is to plan supportive marketing communication, which not only informs customers about the service and persuades them to try it but also has a positive impact on the consumption of the service and enhances a desired image.

If all steps so far are properly carried out, the result should be a concrete offering, which – in the basic package elements as well as in the accessibility, interaction and customer participation aspects of service production and delivery – includes the desired features, which then create the benefits customers seek. This, in turn, should provide the customers with value-creating support to their activities and processes. However, yet another step is required, and that is preparing the organization for producing the desired customer benefits through production and delivery of the augmented service offering.

One of the fatal mistakes that can be made is to believe that the service, once it has been planned, is automatically produced as planned. The discussion of customer perceived quality, and especially of the gap analysis model, in Chapter 5 demonstrated the problems and pitfalls present in producing excellent perceived service quality and showed how complicated a process it is. Hence, the preparation of the organization has to be made an inseparable part of any development of service offerings, otherwise even sound and customer-oriented plans can easily fail.

The preparation of organizations for a desired performance involves the creation of sufficient resources and internal marketing of the new offering to the employees, so that they first understand it, then accept it and feel committed to producing it. In Chapter 14 the concept and phenomenon of internal marketing is covered at some length.

To sum up this discussion of the dynamic model of the augmented service offering, the first stage is always analysis of the customers’ activities and processes and an assessment of what benefits target customers are looking for and would appreciate. Proper market research and use of internal information, for example, from the interface between customers and the organization, should provide management with the necessary knowledge of what customers expect, so that corresponding features can be built into the service. However, innovative market research, such as using ethnographic methods, should be used as well.

The first four steps of the process, analysing the customers’ activities and processes, assessing a customer benefit concept, determining the desired features of the service offering to be produced and defining the service concept, are separate processes. However, the next two phases, developing the basic package and planning the interaction, accessibility and customer participation elements of the augmented service offering in the service process, as well as the last phase, preparing the organization, are inseparable processes. They have to go together, otherwise there is a risk that a good plan will result in a mediocre service. The basic package may include the correct features, but the crucial importance of the accessibility, interaction and customer participation aspects of service production and delivery to total customer perceived quality will not be fully understood or appreciated. Moreover, the need to actively market the new service internally will be neglected, or not taken care of with sufficient attention to detail.

Next, a case study describing a successful development and launching of a new service will be described. The case includes most of the features of the models of the augmented service offering described earlier in this chapter.

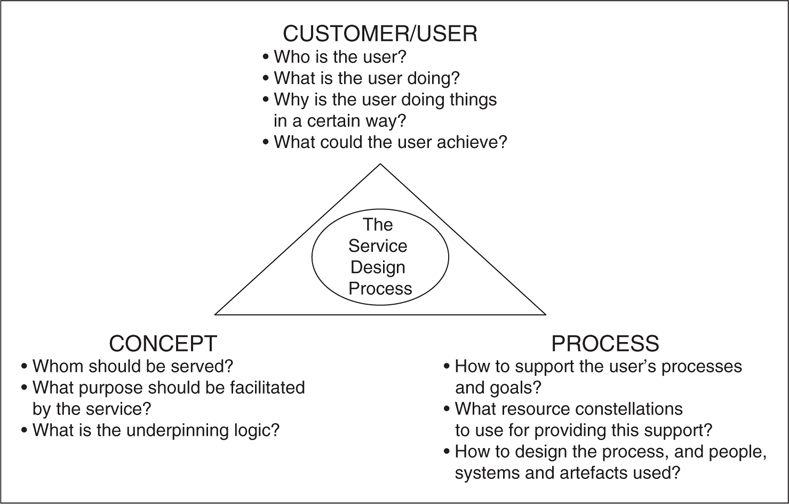

SERVICE DESIGN OR DESIGNING FOR SERVICE

Service design has become an important management issue.15 However, designing services or service activities is too limited a view. It is based on the thought that goods and services are different categories of products, and that service design is developed alongside product design. The service perspective on business, or service logic, does not make such a distinction. Instead it is based on the foundation that service is a way of approaching the firm’s customers in a manner that supports the customers’ everyday processes, in order to facilitate their value creation and contribute to their goal achievement in life or business. Service to customers can be implemented by a firm through any kind of resources or any resource constellations, including any combination of goods, service activities, information, etc.

Following the service logic, designing services is a special case of designing any resource or resource constellation in such a way that they support the customer’s processes. The broader view of designing resources and processes is called design for service.16 Anything, including physical products, can be designed for service, in other words, to serve customers or any users. The opposite is to design a resource, for example, for artistic merit or technical smartness only. However, designing for service does not mean that such goals could not be included in the design process as well.17 Hence, we should distinguish between:

• Design for service.

• Service design.

The latter means designing service activities, whereas design for service means that anything – goods, service activities and constellations of these and other resources – are designed to fulfil the purpose of a service logic:18 to serve the customer or any other user in a value-creating way. Thus, designing for service may include service design, but also design of product elements and other tangible items in an offering. For example, a teapot can be designed to look good, but when used it spills tea onto the table, or it can be designed to function properly without spilling tea outside the cup, and still look good in an artistic sense. In the former situation, the teapot is design as a product only; in the latter situation it is design for service, i.e. to service the user’s tea-drinking habit in a value-supporting manner.

In Figure 7.2 a model of designing for service is schematically illustrated (the designing for service triangle). The three basic parts of the model are the customer/user, whom the resource or offering is designed to serve, the concept guiding the design process, and finally the service process.

As the model indicates, a thorough understanding of the customers’ everyday processes and goals forms the starting point. Such an insight can hardly be gained through traditional market research. Instead ethnographic and similar methods are normally required. The following questions have to be asked and thoroughly answered:

• Who is the user?

• What is the user doing?

• Why is the user acting in a certain way?

• What could the user achieve?

Answers to such questions help the designer understand what opportunities exist to serve the customer, and to serve better than before and perhaps in a totally new way.

FIGURE 7.2

The designing for service triangle.

Then a customer-focused and service-based concept guiding the design process is established. Such a concept can be formulated by answering three simple questions:

• Whom should be served?

• What purpose should be facilitated by the service?

• What is the underpinning logic?

The two first questions provide basic facts for the design process. However, the third question, ‘What is the underpinning logic?’, is the most important one at this stage. Discussing this question and finding a new and unique answer to it, based on the answers to the two customer/user-related questions, may lead to totally new solutions and even revolutionize an industry. This is what Apple managed to do with the iPhone, or what the introduction of the microwave oven decades ago did to cooking. There is an abundance of examples. Not spending time on finding a new logic, when appropriate, only leads to more of the same, and not to a unique new way of serving customer-held purposes.

Finally, the process of designing for service should be attended to. Here the following questions should be answered:

• How to support the user’s processes and goals?

• What resource constellations to use for providing this support?

• How to design the process, and people, systems and artefacts functioning in the process?

When developing the service process and designing the many kinds of resources involved, it is important to take a broad enough look at the process. There are often a whole host of resources and processes involved in providing service. If a required resource or sub-process is neglected and not properly designed, the whole service may fall apart, leading to a dissatisfied and, in the worst case lost, customer. Moreover, when developing and designing resources and processes, their effect on both the technical quality (the outcome of the service process; what the customer is left with) and the functional quality (how the process is perceived) have to be taken into account.

All resources and processes must be developed such that they function as service. They have to be servicized, which means that they are designed and managed in a way that indeed serves the customers. At a minimum the following kinds of resources and processes normally exist in a service process and have to be included in the design process:

Service employees: Employees in customer contacts and in support functions serving internal customers must be trained to do their job technically, but also motivated to perform in a customer-focused and service-oriented manner. Through their leadership managers and supervisors must support such behaviour (internal marketing; see Chapter 14).

Goods and artefacts in the service process: Such resources can be servicized, for example by making them easy to use, easy to maintain, and easily and nicely incorporated in the service process.

Recognized service activities: Activities in a customer relationship which are recognized as service, such as repair and maintenance service and call centres, must be developed so that they successfully support the customer process for which they are designed.

Hidden services: These are service activities that normally are not consider service but administrative, legal, economic, logistical or operational routines, such as complaints handling, invoicing, order-taking and deliveries. Well designed and handled hidden services can have a profound impact on customers’ perception of the service provider and its service. Neglected hidden services, for example resulting in continuous delays in deliveries and unclear or supplier-focused invoices which create problems for customers, can destroy customer relationships and cause much negative word of mouth and discussion in social media.

Servicescapes: The environment where the service process takes place, or the servicescape, includes artefacts, atmosphere-enhancing elements such as music and colours, as well as people, both employees and customers. The way the servicescape looks and functions must be carefully designed to enhance the service experience.

Customers: On the one hand, customers are part of and form the servicescape. On the other hand, customers participate actively in the service process. When designing for service, both these customer roles have to be taken into account. For example, fellow customers must not disturb or in the worst case destroy the service experience of a focal customer, and customers can be given some active roles in service production, such as in Internet banking or self-service stores, or when operating vending machines and digital healthcare control devices.

The goal here is to design and develop a service process that indeed serves the customer. Apple’s iPhone mentioned above is an example of a design and development process where thorough attention was paid to each part of the designing for service process. Another example is the development of a unique elevator system by the Finland-based global elevator company, Kone Corporation. This elevator system serves builders and owners of buildings better than traditional ones. By realizing the need for architects and builders to use as little space for the elevator system as possible, Kone changed the underpinning logic of the elevator concept and came up with the machine room-free system, where the machinery is built into the elevator. This freed space for other use in a building, and in addition it has positive effects on maintenance as well. From only being an elevator and escalator manufacturer, Kone is today known as a service business ‘dedicated to people flow’.

DEVELOPING A SERVICE OFFERING IN THE MARKETSPACE

Today, an ever-increasing number of offerings of goods and services are marketed over the Internet and mobile phones. A large virtual marketspace has developed alongside the traditional physical marketplace. Regardless of whether they are related to physical goods or services, the purchase and consumption of Internet offerings can be described as process consumption and can be seen to reflect the key characteristics of service and service consumption.

The customer has to be able to operate the system in order to be able to get information about goods or services, to order them, to pay for them or arrange for payment, as well as possibly to make detailed inquiries and receive responses to those, and to perform a number of other activities related to the offering that is considered, and in many cases to use the service. In the end this process should of course lead to an outcome as in the case of any service. The quality of an Internet offering is dependent on the perceived quality of the process (the functional quality dimension) of using the Internet as a purchasing and sometimes also consumption instrument as well as on the perceived quality of the outcome (the technical quality dimension). As can be concluded from the description above, the offering of any physical good or service over the Internet is a service. Therefore, marketers who wish to use the Internet to offer their goods or services to customers should take care to design their offerings as service offerings that customers perceive and evaluate as service.

In the following sections the augmented service offering is developed into a service offering for the Internet, called the NetOffer model.19

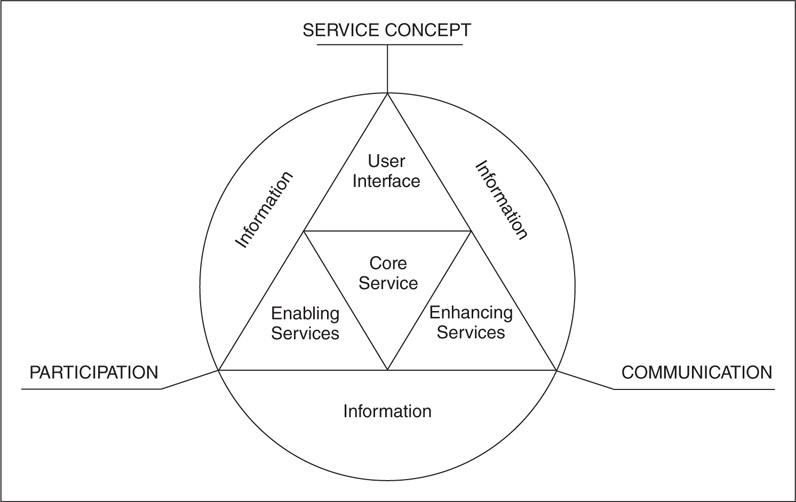

THE NETOFFER MODEL

In this section the full NetOffer Internet offering model is described. The elements of the basic service package, i.e. the core service as well as the enabling and enhancing services, are similar to those in the original model. However, the augmentation elements of the Internet offering are different, because accessibility and interaction aspects of the process cannot be kept apart. Instead, they merge into one communication element in the augmentation process. The NetOffer model is illustrated in Figure 7.3.

The service concept is the foundation for the service package and for the augmentation of the package into an Internet offering. However, unless there is an easy-to-understand and easy-to-use website, i.e. a well-functioning interface between the user and the firm, there is no access to the Internet offering. Therefore, compared with the model for the traditional marketplace, an additional element termed user interface (UI) is included in the service package. The technical as well as the functional quality dimensions of the offering are dependent on the design and functionality of this interface. If the interface between the customer and the computer is not functional, the service that the firm is trying to supply is unusable and therefore worthless. The user interface consists of every aspect of the computerized interaction. The site must be easy to navigate and all the links must be clear and logical. The colours and graphics must be attractive and the text easy to process. Moreover, the speed of the server must be sufficient and the types of fonts must be appropriate. These are all issues that concern the quality of this interface.

The UI is part of the service package, because it more or less has to sell the offering itself. It has to be visually appealing and technically functioning. There are no marketers present who can convince the potential customer about the superiority of the offering. It is easy for a customer to switch to another website, and therefore a visually uninteresting or difficult-to-grasp interface quickly makes a potential customer leave the site. In that case a sales opportunity is lost.

FIGURE 7.3

The NetOffer model.

Source: Grönroos, C., Heinonen, F., Isoniemi, K. & Lindholm, M., The NetOffer model: a case example from the virtual marketspace. Management Decision, 38(4); 2000: p. 250. Reproduced by permission of Emerald Insight.

In an offering on the Internet, information is a critical element. Therefore, the inner triangle in the figure illustrating the service package is placed within a circle of information. This circle represents the information supply that has to be provided when offering goods or services on the Internet. Information is a vital part of any such offering and it is a part of all the different elements of the model. Information provided by the firm as well as by the customer is the fuel that makes the core, enabling and enhancing services function and that drives the UI.

As Figure 7.3 shows, the augmentation of the service package includes two elements instead of the three in the original augmented service offering model. These elements are:

Customer participation.

Communication.

Customer participation denotes the skills, knowledge and interest of customers as far as operating the UI is concerned, i.e. as co-producers of the service, so that they can make a purchase, ask questions and make complaints, receive responses, or go to links offered on the website. Customer participation can also relate to discussion group activities involving customers and potential customers and other users of a given website. Through an easily manageable UI and supportive information about various aspects of the system and the parts of the service package, the firm can assist customers in participating. Thus, customer participation becomes partly a co-production activity, partly a co-creation of a solution for the customer’s value-creating process.

On the Internet, accessibility and interaction involve communicating. Getting access means communicating with the website using the navigation system of the UI, and interacting with the website means communicating with the system through e-mail or other parts of the system. Interacting becomes part of communicating. Hence, interaction and accessibility in the original augmented service offering model merge into one element, where the common denominator is communication. Sometimes communication is two-way, as in the case of inquiries through e-mail. Sometimes it is one-way, as in the case of making a direct purchase or giving credit card information when paying for goods or services. The communication element of the Internet offering illustrates the dialogue that can occur between the service provider and the customer. This dialogue can include all possible media of communication, for example by e-mail, telephone, letters, message boards, etc.

By facilitating user-oriented communication, the Internet marketer helps the customer to purchase and consume goods and services offered on the Internet. Through this communication and assuming appropriate customer participation skills, the functional quality of the Internet offering (the how dimension) is enhanced and the customer is able to perceive the technical quality of what is offered (the what dimension). Good total perceived quality and value are created.

Finally, when goods and services are bought on the Internet, it is not enough that the Internet offering functions well and creates an acceptable perceived service quality. The purchases have to be delivered to the customer as well in a quality-enhancing way. Sometimes the delivery can take place electronically, as in the case of electronic airline tickets that can be printed by the consumer. Sometimes the goods are delivered in the physical marketplace.

NOTES

1. See Grönroos, C., Service Managing and Marketing. Managing the Moments of Truth in Service Competition. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1990. In the service management and service marketing literature, surprisingly little attention has been devoted to the understanding and conceptualization of service or service offerings. An example of one of the few attempts is Storey, C. & Easingwood, C.J., The augmented service offering: a conceptualization and study of its impact on new service success. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 15(4), 1998, 335–351.

2. There is a limited but growing number of publications on the design and development of new services. See, for example, de Brentani, U., New industrial service development: scenarios for success and failure. Journal of Business Research, 32(2), 1995, 93–103; de Brentani, U. & Ragot, E., Developing new business-to-business services: what factors impact performance? Industrial Marketing Management, 25(6), 1996, 517–530; Edvardsson, B., Quality in new service development: key concepts and a frame of reference. Internal Journal of Production Economics, 52(1–2), 1997, 31–46; Edvardsson, B. & Olsson, J., Key concepts for new service development. The Service Industries Journal, 16(2), 1996, 140–164; Martin Jr., C.R. & Home, D.A., Service innovations: successful versus unsuccessful firms. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 4(1), 1993, 49–65. See also Kokko, T., Offering Development in the Restaurant Sector – A Comparison between Customer Perceptions and Management Beliefs. Helsingfors, Finland: Hanken Swedish School of Economics, Finland, 2005.

3. See, for a few early examples, Normann, R., Service Management, 2nd edn. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1991; Langeard, E. & Eiglier, P., Servuction. Les Marketing des Services. Paris: John Wiley & Sons, 1987; Lehtinen, J.R., Quality-oriented Services Marketing. University of Tampere, Finland, 1986.

4. This point of view goes back to the argument put forward by Theodore Levitt: ‘Having been offered these extras, the customer finds them beneficial and therefore prefers doing business with the company that supplies them.’ See Levitt, T., After the sale is over. Harvard Business Review, Sept–Oct, 1983, 9–10.

5. Lovelock, C., Competing on service: Technology and teamwork in supplementary services. Strategy & Leadership, 23(4), 1995, 32–47. Recently this model has been studied and updated in Frow, P., Payne, A. & Ngo, L., Diagnosing the supplementary services model: empirical validation, advancement and implementation. Journal of Marketing Management, 30(1–2), 2014, 138–171.

6. Grönroos, 1990, op. cit. and Grönroos, C., Developing the service offering – a source of competitive advantage. In Surprenant, C. (ed.), Add Value to Your Service. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association, 1987.

7. I am grateful to Anton Molander and Daniela Voullième, two students in my Service Management and Marketing class, who in a project presentation made the point that the terms enabling and enhancing services better communicate the meaning of the underlying constructs than the terms facilitating and supporting services which were used in previous editions of this book.

8. Grönroos, 1990, op. cit. and Grönroos, 1987, op. cit. In the service development literature, especially customer involvement has been studied. See, for example, Carbonell, P., Rodriges-Escudero, A.I. & Pujari, D., Customer involvement in new service development: an examination of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 6(5), 2009, 536–550.

9. See Prahalad, C.K. & Ramaswamy, V., The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2004 and Wikström, S., Value creation by company–consumer interaction. Journal of Marketing Management, 12, 1996, 359–374.

10. The relationship between image as brand image and firm reputation and service offerings have been studied in Cretu, A.E. & Brodie, R.J., The image of brand image and company reputation where manufacturers market to small firms: a customer value perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(2), 2007, 230–240.

11. Bitner, M.J., Brown, S.W. & Meuter, M.L., Technology infusion in service encounters. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 2000, 138–149. See also Kristensson, P., Matthing, J. & Johansson, N., Key strategies for successful involvement of customers in new technology-based services. Journal of Service Industry Management, 19(4), 2008, 474–491.

12. Although this case is not new, it clearly demonstrates the potential of the augmented service offering model.

13. Ostrom, A.L. & Hart, C., Service guarantees. Research and practice. In Swartz, T.A. & Iacobucci, D. (eds), Handbook in Services Marketing & Management. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2000, pp. 299–313 and Hart, C.W.L., The power of unconditional guarantees. Harvard Business Review, 66(Jul–Aug), 1988, 54–62.

14. Ostrom, A.L. & Iacobucci, D., The effects of guarantees on consumers’ evaluation of services. Journal of Services Marketing, 12(6), 1998, 362–378. See also Wu, C.H.J., Liao, H-C., Hung, K-P. & Ho, Y-H., Service guarantees in the hotel industry: their effects on consumer risk and service quality perceptions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3), 2012, 757–763, and McCollough, M.A., Service guarantees: a review and an explanation of their continued rarity. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 14(2), 2010, 27–54.

15. See, for example, Patricio, L., Fisk, R.P., Falcao de Cunha, J. & Constantine, L., Multilevel service design: from customer value constellation to service experience blueprinting. Journal of Service Research, 14(2), 2011, 180–200.

16. See Kimbell, L., Designing for service as one way of designing services. International Journal of Design, 5(2), 2011, 41–52. See also Meroni, A. & Sangiorgi, D., Design for services. Surrey: Gower Publishing Ltd, 2011.

17. Moreover sometime, for example, designing for artistic goals may be designing for service. For instance, a painting serves the owner or any viewer by its artistic qualities.

18. Wetter-Edman, K., Sangiorgi, D., Edvardsson, B., Holmlid, S., Grönroos, C. & Mattelmäki, T., Design for value co-creation: exploring synergies between Design for Service and Service Logic. Service Science, 6(2), 2014, 106–121.

19. Grönroos, C., Heinonen, K., Isoniemi, K. & Lindholm, M., The NetOffer model: a case example from the virtual marketspace. Management Decision, 38(4), 2000, 243–252.

FURTHER READING

Bitner, M.J., Brown, S.W. & Meuter, M.L. (2000) Technology infusion in service encounters. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 138–149.

Carbonell, P., Rodriges-Escudero, A.I. & Pujari, D. (2009) Customer involvement in new service development: an examination of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 6(5), 536–550.

Cretu, A.E. & Brodie, R.J. (2007) The influence of brand image and company reputation where manufacturers market to small firms: a customer value perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(2), 230–240.

de Brentani, U. (1995) New industrial service development: scenarios for success and failure. Journal of Business Research, 32(2), 93–103.

de Brentani, U. & Ragot, E. (1996) Developing new business-to-business services: what factors impact performance? Industrial Marketing Management, 25(6), 517–530.

Edvardsson, B. (1997) Quality in new service development: key concepts and a frame of reference. Internal Journal of Production Economics, 52(1–2), 31–46.

Edvardsson, B. & Olsson, J. (1996) Key concepts for new service development. The Service Industries Journal, 16(2), 140–164.

Frow, P., Payne, A. & Ngo, L. (2014) Diagnosing the supplementary services model: empirical validation, advancement and implementation. Journal of Marketing Management, 30(1–2), 138–171.

Grönroos, C. (1987) Developing the service offering – a source of competitive advantage. In Surprenant, C. (ed.), Add Value to Your Service. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association.

Grönroos, C. (1990) Service Managing and Marketing. Managing the Moments of Truth in Service Competition. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Grönroos, C., Heinonen, K., Isoniemi, K. & Lindholm, M. (2000) The NetOffer model: a case example from the virtual marketspace. Management Decision, 38(4), 243–252.

Hart, C.W.L. (1988) The power of unconditional guarantees. Harvard Business Review, 66(Jul–Aug), 54–62.

Kimbell, L. (2011) Designing for service as one way of designing services. International Journal of Design, 5(2), 41–52.

Kokko, T. (2005) Offering Development in the Restaurant Sector – A Comparison between Customer Perceptions and Management Beliefs. Helsingfors, Finland: Hanken Swedish School of Economics, Finland.

Kristensson, P., Matthing, J. & Johansson, N. (2008) Key strategies for successful involvement of customers in new technology-based services. Journal of Service Industry Management, 19(4), 474–491.

Langeard, E. & Eiglier, P. (1987) Servuction. Les Marketing des Services. Paris: John Wiley & Sons.

Lehtinen, J.R. (1986) Quality-oriented Services Marketing. University of Tampere, Finland.

Levitt, T. (1983) After the sale is over. Harvard Business Review, Sept–Oct.

Lovelock, C. (1995) Competing on service: technology and teamwork in supplementary services. Strategy & Leadership, 23(4), 32–47.

Martin Jr., C.R. & Horne, D.A. (1993) Service innovations: successful versus unsuccessful firms. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 4(1), 49–65.

McCollough, M.A. (2010) Service guarantees: a review and an explanation of their continued rarity. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 14(2), 27–54.

Meroni, A. & Sangiorgi, D. (2011) Design for services, Surrey: Gower Publishing Ltd.

Normann, R. (1991) Service Management, 2nd edn. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Ostrom, A.L. & Hart, C. (2000) Service guarantees. Research and practice. In Swartz, T.A. & Iacobucci, D. (eds), Handbook in Services Marketing & Management. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, pp. 299–313.

Ostrom, A.L. & Iacobucci, D. (1998) The effects of guarantees on consumers’ evaluation of services. Journal of Services Marketing, 12(6), 362–378.

Patricio, L., Fisk, R.P., Falcao de Cunha, J. & Constantine, L. (2011) Multilevel service design: from customer value constellation to service experience blueprinting. Journal of Service Research, 14(2), 180–200.

Prahalad, C.K. & Ramaswamy, V. (2004) The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Storey, C. & Easingwood, C.J. (1998) The augmented service offering: a conceptualization and study of its impact on new service success. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 15(4), 335–351.

Wetter-Edman, K., Sangiorgi, D., Edvardsson, B., Holmlid, S., Grönroos, C. & Mattelmäki, T. (2014) Design for value co-creation: exploring synergies between Design for Service and Service Logic. Service Science, 6(2), 106–121.

Wikström, S. (1996) Value creation by company–consumer interaction. Journal of Marketing Management, 12, 359–374.

Wu, C.H.J., Liao, H-C., Hung, K-P. & Ho, Y-H. (2012) Service guarantees in the hotel industry: their effects on consumer risk and service quality perceptions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3), 757–763.