CHAPTER 12

SOCIAL MEDIA IN SERVICE MANAGEMENT AND MARKETING

Written by Johanna Gummerus

“In social media, a firm is just as good as its customers think it is – the truth leaks out one way or another.”

INTRODUCTION

This chapter looks at the role of social media in service management and marketing. Also, different types of social media are discussed. Then, the chapter presents the social media communication circle, after which the influence of social media on service marketing and management will be explained. After reading the chapter the reader should know what kinds of social media there are, how they function, and how firms can adapt their marketing to various social media.

BACKGROUND TO SOCIAL MEDIA

Social media refer to all those new online media that allow actors to generate and share content with others on a large scale. The content can be text, pictures, video, or audio. The social media platforms enable and encourage sharing, meaning that the content spreads fast to a wide online audience, causing an enormous ripple effect. In essence, then, social media constitute a new way with which people connect to each other.

From a marketing perspective, the most important aspect of social media is their pervasiveness and influence in people’s lives. Most people are today connected to some social media, be it social networking sites1 such as LinkedIn and Facebook, microblogging services such as Twitter, communication apps such as WhatsApp and Kik, content sharing communities such as YouTube, SlideShare, Instagram and Pinterest, crowd sourcing or crowd funding platforms,2 different online forums or blogs, or virtual worlds such as Second Life or Habbo Hotel. As consumers are continuously connected to different social media, they share with others their everyday life, including their interactions and experiences with firms. Because of the mass sharing of information, consumers are also better informed and thereby they become more empowered3 – they can more readily find and evaluate service providers, brands, or products. Also, because consumers are increasingly able to learn from each other, they may question expert opinions based on the information they have accessed online. The pervasiveness and continuous mass sharing of experiences in social media further leads to transparency of firm actions, as both positive and negative firm activities spread out far quicker and to a wider audience than before, and many firms perceive an increasing lack of control of what is being said about them. Quite frequently, customer stories spread from social media to traditional media e.g. through journalists who skim through social media content to find appealing stories.

Another important aspect relates to the content that is created and shared by people in social media, the user generated content (UGC), which refers to the content that is created voluntarily by ordinary users and not by professionals. This content can vary from a simple grade given for a product, brand or firm on a review site to complex information or creative efforts such as music, videos or virtual items. A single consumer can, in social media, get his voice heard by millions of listeners. Customers often create content that in one way or another relates to companies. It may be positive, for example praise for a company or a brand, or negative, such as sharing a bad experience. The social media review sites such as YELP! (www.yelp.com) collect and aggregate consumer opinions and experiences, and as they offer a continuously updated pool of information, these assessments influence customer decision-making and behaviour. Review sites may also act as middlemen as TripAdvisor does (www.tripadvisor.com), or concentrate on assessing firms from an employee’s viewpoint, as done at Glassdoor (www.glassdoor.com). Importantly, customers find the content generated by other users more trustworthy and interesting than the content firms put online.4 In particular more creative content, such as music, spreads quickly in social media. The Disney film Frozen, for example, has inspired video bloggers to create videos on how to get the perfect look of the main characters in the film, and these can be found on, for example, YouTube, where other users can grade and comment on them. The viewer numbers and grades then influence how high up the content appears on the site, emphasizing popular content. Another well-known example is that of the Canadian country singer Dave Carroll, whose guitar was damaged when he flew with United Airlines. After almost a yearlong battle to get the damages covered, the airline turned down Carroll’s request for compensation. The upset musician then wrote a song about his experiences and put it on YouTube, from where it spread virally to millions of viewers and was caught up by journalists and taken up in other media.5 The video resonated with customers who had been maltreated by United and other big airlines, and led to United Airlines share prices plunging.6. Because of the video, Carroll became a popular breakfast show guest and has toured talking about airline quality, written a book about his experiences entitled United Breaks Guitars, and finished a trilogy of songs about his United Airlines experience. The side effect of UGC is that because of the astounding amount of content that competes with firm-generated content, gaining visibility in social media may be challenging.

A third important aspect of social media is that customers tend to opt-in in these media, that is, they choose and become engaged in sub-groups within different social media that by default involve a particular interest. Such sub-groups may, for example, be brand sites on Facebook, groups in LinkedIn, blogs specializing in different topics, YouTube channels, pinned interests, or online discussion fora. Furthermore, the users who have opted-in tend to be experts or highly involved in the topic. This means that many social media platforms enable firms to reach particular niche segments of customers who have signalled that they are interested and willing to learn more about a particular topic.

Fourthly, social media offer a platform where firms and customers may interact. Consequently, manufacturers and suppliers who have not necessarily traditionally had any direct contact with end customers are able to listen to and engage in dialogues with the end customers in social media. One such case is the Finnish dairy company Valio, that has used social media to develop new protein-rich and low-fat quark products together with the weightlifting community.7 Similarly, social media make consumer opinions more visible for companies, as they are able to monitor what is said about them and respond directly to customers.

Fifthly, social media may have a direct influence on the service experience during consumption. Tweeting with others while watching a TV show or being engaged in any service process has the potential to change both the collective service experience and the experience of the individual consumer. Sharing impressions and thoughts about the service between like-minded persons changes the service experience. For example, the experience of a TV show may, through this use, change considerably from what was intended by the producer. In this way social media lifts the service experience to a new level, and offers risks and opportunities for the service provider. Kai Huotari, who has studied the impact of social media on service experiences, calls this phenomenon experientializing.8 An interesting and challenging aspect of experientializing is the fact that it takes place outside the direct reach of the service provider.

Finally, social media space is fast-moving and therefore requires a totally new type of communication from companies. Consequently, in many cases the most efficient service and relationship-building activities require the ability to quickly react to unplanned activities taking place. One such instance happened during the 2013 Super Bowl power blackout, when Oreo biscuits were quick to tweet ‘You can still dunk in the dark’, referring to dunking the biscuit to liquid in order to enjoy it. This quick, snappy remark raised a wave of positive reactions among the public, journalists and marketing professionals.9 The main winning factor was not the ingeniousness of the message, but rather the quick reaction to the disruption. Thus, the companies that are agile in the social media environment are the ones most likely to benefit from them.

Next, we will discuss the different social media types.

DIFFERENT TYPES OF SOCIAL MEDIA

Social media can be understood by looking at the different characteristics they have. The early versions of social media, virtual communities, referred to groups of people who interacted with each other because they were either enthusiastic or knowledgeable about something. Consequently, virtual communities were divided based on whether the users focused on information exchange or on social interaction, and whether the interactions were freely accessible by everybody or took place within a closed circle of people.10 Of late, differentiations between information exchange and social interaction are difficult to make, because the information exchange itself has become a social activity.

More recently, another way to understand how the social media platforms differ has been introduced, based on media content, and the role of the participant. Media content concerns the social presence/media richness. Social presence/media richness reflects the medium’s ability to provide information to decrease uncertainty and replicate real-life sensory cues.11 The second aspect that takes up the role of the participant refers to the degree of self-presentation/self-disclosure to which the participants engage in divulging personal information.12 Virtual worlds such as Second Life or Habbo Hotel are examples of social media with high self-presentation/self-disclosure, because people are able to create avatars that impersonate them. The virtual world participants are able to interact with others with the help of the avatars, expressing their personality with clothing, use of words, and different symbols that represent their interests. Virtual worlds are also high in social presence/media richness because the verbal and visual cues ameliorate ambiguity. If self-disclosure is high, the interactions within the media are more personal and consumers may find it easier to connect with each other, and with the firm.

Another way of understanding social media is through the half-life and the depth of information. The half-life of information refers to how long the information is available13 on the screen, and social media differ in this aspect. On Kik for example, the messages come up and disappear. Facebook postings are more long-lived as they can be found on the news feed or the person’s or firm’s site that posted them. The depth of information in turn means how rich, numerous, and diverse the viewpoints presented on a topic are. It can vary between shallow information depth in, for example, blogs that, although they may be rich, represent mainly one person’s (the blogger’s) perspective and are thus classified as shallow, to the deep information presented in specialized communities that aggregate several people’s views.

A challenge in many social media applications is that information emerges and then disappears in the flow of new posts. Therefore, customers may be exposed to firm postings to different degrees, some noticing all of them, some only few and some none. Consequently, firms need to understand social media in terms of media richness, participant self-presentation/self-disclosure, information depth and information longevity.

COMPANY PARTICIPATION IN SOCIAL MEDIA

In order to interact with potential, current and past customers, companies can either establish their own social media platforms, such as corporate blogs or company-sponsored communities, or employ external social media platforms.14 Company-owned virtual communities are valuable because the company is able to set the rules for the community, direct activities and gather data from the users. However, setting up own communities may be costly, and what is even more crucial, it may be difficult to gain visibility and attract participants to them.

Companies may also choose to tap into the extant social media platforms that already have a wide audience. Most social media platforms offer firms the opportunity to establish company sites, or include their own content on the platform. If companies establish presence in external social media sites, they have to follow the rules and regulations of the platform owner. Planning activities may however be challenging because the social media platform owners may change the rules after innovative marketing campaigns. For example, the Swedish furniture company IKEA launched a Facebook campaign to promote their new store in Malmo. During the campaign, the store manager posted, within a two-week period, twelve pictures of IKEA catalogue-type photos on Facebook. On the photos, the customers could tag15 pieces of furniture. Whoever tagged the furniture first would win it. The marketing campaign received a huge amount of ‘likes’ and spread among people who recommended the campaign to their peers. However, Facebook soon banned these types of campaigns.

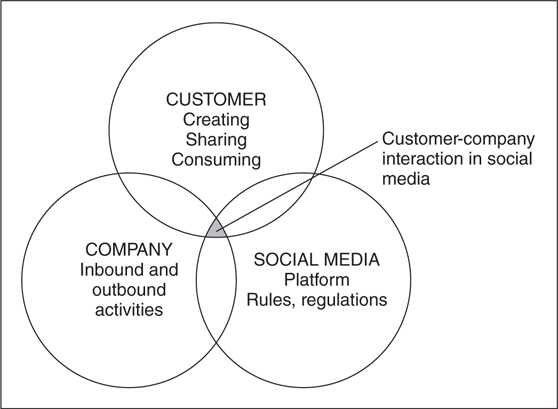

To illustrate the contingency of company participation in social media, Figure 12.1 depicts how company–customer interaction takes place in social media.

Figure 12.1 shows how customer activities, company activities, and social media platforms together create the sphere where customer–company interactions take place in social media. The three areas are interdependent. Both firm and customer activities are dependent on the social media platform. For example, Twitter allows only 160 characters in the messages sent, which forces users to compress messages and use hashtags (# and the connecting word) to link their message to other messages where the word that has been tagged is used. The customer activities of creating, sharing and consuming also influence what firms are able to do. For example, customers’ tendency to share company-related content defines how easy and costly it is to spread messages in social media. Customers may also have differing expectations about how firms are allowed to act in different social media. In general, social media that are not owned by the company are mainly meant for customer-to-customer interaction,16 and consumers may not be positively attuned to company participation. Customers generally tend to think that firms should openly admit if they are behind marketing messages. Unfortunately, not all companies do this. Companies may seed content and comments to enhance information spreading among customers, evoke interest among them, or encourage discussions without telling that they are behind this.

FIGURE 12.1

Customer–company interaction in social media.

Because of the special media characteristics and the interdependence between company and customer activities, social media impact the traditional communication circle. This will be discussed next with the help of the social media communication circle.

SOCIAL MEDIA COMMUNICATION CIRCLE

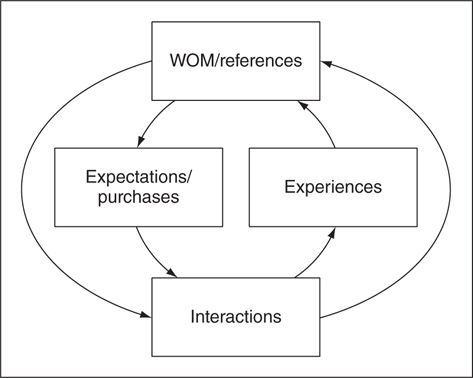

Social media challenge the traditional communication circle, for several reasons: the communication speeds up, the customers may already during the service encounter share their experiences with others and the firm, and the customers may seek social support during the encounter. For example, a customer may, while waiting to be seated in a restaurant or during a meal, comment on the service or take photos of the food and the interior, and share them in social media. Figure 12.2 depicts the social media communication circle that is modified from the traditional communication circle.

The basic elements of the social media communication circle are the same as in the traditional communication circle: customer expectations, interactions, experiences, and word of mouth (WOM). In the traditional communication circle, expectations, interactions, experiences, and WOM follow each other, and the circle closes as the WOM influences expectations. However, in social media, as the customer is constantly connected to social media, the interactions and WOM may take place simultaneously. Because of this, as the concept of experientializing mentioned earlier demonstrates, WOM may even become a part of the interaction and the final service experience. For example, a customer may go to a shop to buy a new outfit for a family occasion and, while in the shop, take a photo of the dress and send it to her WhatsApp list to receive feedback from family members, and depending on the response, ending up buying the dress or not. The response may also shape how the customer experiences the whole shopping spree as either immensely humiliating (‘How could you even consider that horrible rag?’) or as delightful (‘Where on earth did you find that lovely outfit!’). Consequently, the WOM and the service interaction become intertwined and interdependent when social media communication is involved.

FIGURE 12.2

Social media communication circle.

THE INFLUENCE OF SOCIAL MEDIA ON SERVICE MARKETING

A number of aspects in service management and relationships become highlighted due to social media.

First of all, as both positive and negative experiences of customers will spread, the importance of making, enabling and keeping promises is accentuated. Firms must make sure that the promises they make are really kept and fulfilled, because any problems in service quality will be communicated quickly in the social media space. This means that it is crucial to prevent the negative word of mouth from emerging by removing the causes for dissatisfaction. Essentially, firms need to acknowledge even more than before that customer-to-customer communications are beyond their control. In fact, many brands have hate websites that collect negative customer experiences.17 The existence of such communities and of any type of word of mouth can also be seen as a positive sign – the brand evokes feelings and is not within customers’ sphere of indifference, which may be far more dangerous. The role of part-time marketers18 in particular becomes pivotal, as they influence customer satisfaction directly and will be referred to in online reviews. Consequently, social media also influence how firms should organize their activities internally. The personnel need to have a clear understanding of what is expected of them, that is, role divisions, such as who is responsible; how quickly and often to respond; and how to deal with different types of issues that arise online. It is important that the personnel are allowed to show their personality in their communications with customers. All in all, the firm will have to rely on more direct communication, showing authenticity and identity. Thus, firms should encourage the employees to use their own genuine, personal interaction style.

Secondly, the agility of the social media landscape has consequences for firms. Since consumers are connected to social media, firms are able to instantaneously serve their customers. This is particularly useful in cases where unexpected situations arise, or when companies need to access customers quickly. In emergencies, when company web pages or contact centres would not manage the large number of customer contacts, different social media can be utilized to communicate with customers, as they can be updated quickly and are technically fit for mass communication. Also, through social media, marketers may find possibilities for reacting quickly to other more mundane real-life events and engage the audience in a dialogue, for example take part in conversations taking place in the general press. The instantaneous visibility of the customers’ service experiences also means that firms can monitor their service performance online in real time. With the help of online monitoring tools and feedback systems, firms can reach and respond instantly to negative customer feedback, and identify and correct flaws in service processes. For example, the Finnish airline company Finnair screens customers’ Twitter postings to recognize glitches in customer flight experiences, after which they analyse the underlying causes of these service failures and, when applicable, correct internal service processes. Firms may also find it easier to manage the perishability of face-to-face services by promoting the service in social media at times when the service would otherwise go unsold, for example during off-season or if demand otherwise fluctuates.

Thirdly, the new types of communications in social media including audio, video, and pictures have several implications for the communication between customers and between customers and the firm. Customers are able to provide evidence in the form of pictures and video to back up any claims they make about the firm. The social media interactions that are supported by visual evidence are more tangible than traditional word of mouth that consists mostly of verbally communicated stories. Consequently, experience services that the customer is only able to evaluate after consumption19 may become higher in search qualities (aspects that can be evaluated before consumption). Also, this content is stored and stays online, to be found even years after the initial incident. On the one hand, firms are challenged by heightened requirements for quality management since deviations from acceptable levels of quality have even more powerful consequences due to widely spreading electronic word of mouth. On the other hand, the firms excelling in customer service will reap benefits from positive reviews and customer experiences.

Fourthly, social media also make it possible for customers to show their engagement to the firm or brand in multifaceted ways that entail both purchase and non-purchase behaviour.20 Customer engagement captures customers’ positive firm-related behaviours. It includes both consumer-to-firm interactions and consumer-to-consumer communications about the firm or the brand. Engagement behaviours may include discussing, commenting, information searching and taking part in opinion polls, as well as communicating through brand communities, blogging and other social media. When customers engage in different activities, they also derive different benefits. The benefits that firms try to create with customers may be economic (for example through lotteries, discounts), entertainment-related (for example games and videos), and social benefits (for example recognition, discussions with peers).21 In many cases, customers engage in multiple behaviours. Customer community engagement behaviours such as content liking, reading and commenting on messages influence the benefits that customers receive from their engagement with the community. Companies should, however, be careful if they focus on economic benefits such as bonuses or lotteries, because they may not influence customer satisfaction or loyalty in a positive way. Rather, they may attract bargain-hunters who seek out cheap offers but have no intention of purchasing for full price. Also, people may become accustomed to low prices, waiting for the next offer and only buying then.

Fifthly, firms need to reconsider the division of work and whether to employ the ‘wisdom of the crowds’,22 particularly when it comes to service innovation. In innovation work, companies may employ customers in several areas – externalizing activities may pay off in idea generation, developing the ideas further, or commercializing them.23 These types of activities, where the company views innovation work more broadly in a network setting, are labelled ‘open innovation’. Open innovation includes both importing innovative ideas into the company and exporting intellectual capital.24 Crowdsourcing can extend from innovation work to any redivision of labour, so that a company can renegotiate the roles taken by its customers and other interest groups. Although customers often happily engage in service development work, the company needs to make sure that the innovation process is perceived as being fair and transparent, and that the customers are satisfied with the innovation outcome.25 In some cases, the customer involvement may be rather straightforward, such as inviting customers to test a new concept or become brand ambassadors by displaying them while using the brand. For example, the Finnish online yoga service provider Yoogaia (www.yoogaia.com) has been using Facebook for developing and launching its service.

Sixthly, as in other media, companies need to connect with customers and support them in their daily activities, but the particularity of social media is that companies need to consider why customers would engage in word of mouth or act as advocates online. For example, companies who wish to encourage private bloggers to spread word of mouth about the company need to consider why such individuals blog in the first place. Some reasons include blogging because the activity itself is rewarding, because bloggers feel that the content they produce is valuable, and because of social connectivity to the readers of the blog.26 Consequently, if the company is able to help the blogger to reach such benefits, for example by helping them to get exclusive content, improve their blogging skills, or help them in communicating with the readers, the blogger is more likely to accept collaboration. In the same manner, end customers value company social media activities that help them to achieve their own goals, such as to receive recognition, to be entertained, or to acquire economic benefits.27 In some cases, such as when involving the firm’s fans, the task may be quite straightforward – fans are likely to accept and share content further in their network. For example, many sports fan clubs share information about coming events, players or league news, allow fans to post content, promote events, and arrange contests for fans.

Finally, it is noteworthy that companies have different degrees of closeness to the customers. For example, companies that typically use third-party suppliers, such as manufacturers of consumer goods, have in social media a direct channel through which they can communicate with the end customers. However, their challenge, as they do not own the customer data, is to figure out whether social media marketing campaigns in fact have an effect on customer behaviour or not. The providers of experiential services that are not typically able to be evaluated beforehand, such as travel, music, or theatre, can encourage customers to spread word of mouth and thus make the service more appealing for potential clients. Similarly, services that require physical contact such as car repair, health care or hairdressers, can encourage the customers to share their experiences to reduce potential customers’ risk perceptions. Manufacturers of products that require long production processes, particularly if they have highly-involved customers, may again interact with customers and make the product distinguishable for them by opening up the firm-internal production processes. Such an approach would mean that the provider invites the customers to get acquainted with the firm’s daily activities.

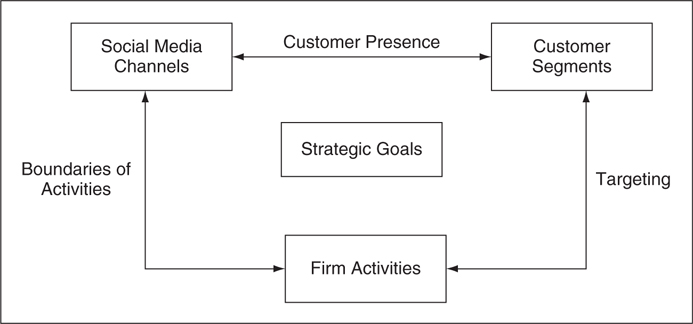

FIGURE 12.3

Company social media strategy triangle.

FIRM ACTIVITIES IN SOCIAL MEDIA

Figure 12.3 demonstrates how firms should plan their social media activities.

The model consists of four parts: strategic goals that define what should be achieved, the choice of the social media channels, the customer segments that one wishes to reach, and the firm activities that are undertaken to reach the strategic goals. These four parts are all interdependent and interlinked with the environment. For example, the choice of appropriate strategy is dependent on the customer market that is targeted, and therefore different markets may have different strategic goals. For example, a firm that has only just entered a new market will likely aim for becoming more well known, whereas an established player on the market will more likely be interested in serving current customers or learning from them. The same logic applies for different sub-markets. For example, a company may have as a strategic goal branding their hotel chain as the most appealing option for business travellers.

Firms should, if they decide to participate in social media, start by setting their strategic goals. Setting measureable goals is important, because this allows the follow-up of how well different actions lead to desired results. Also, well-defined goals allow the selection of customer segments that will be targeted, the choice of appropriate tactics, and the measurement of success/failure.

General strategic goals for social media comprise increasing brand awareness, serving customers, generating traffic or profits, and collecting customer inputs. Brand awareness is important, because it means that the company is within the customer’s consideration set, and it is particularly relevant to reach in new markets where the company is poorly known. Brand awareness can be evaluated with relatively simple measures such as the number of content viewers, and how these evolve over time. Serving customers in social media offers an important opportunity to engage in dialogue with customers and support them before, after, and during service use. Increasing traffic to the company website is perhaps the most straightforward goal, because it can be defined and measured effectively. Collecting customer inputs or ‘listening in’ to understand customers better is an important goal. However, this goal is difficult to measure, as it not only refers to noticing customer inputs but also learning from and acting upon them.

The social media channel choice is closely interlinked with the type of users that they have and the type of company activities that they enable. Social media vary in terms of who the consumers are that use them; how widely they are used; what type of content is published and shared; the consumer activities that the media enable; and the degree of involvement from companies. The company has to consider where it can reach its customers the best. In many cases, media agencies are used to choose appropriate media, but the company must understand how the different media work.

Company activities in social media are contingent upon the channel used and the customers the company wants to reach. The way companies are able to interact with their customers in social media depends on several aspects. First of all, the customers engage in different activities in social media, and may be willing to different degrees to interact with companies. Notably, only a minority of people create content, but their contribution is central for the vitality of social media, and it can become a form of viral marketing when customers promote the company and/or its offerings. For this reason, it is important to encourage and acknowledge customer content creation. It should be kept in mind that for each person that contributes, there are typically ten people who lurk, that is, follow the social media content. These lurkers may be just as loyal towards the brand as the active participants.28 Thus, it is dangerous to assume that it is only worth maintaining relationships with the active participants.

From a firm perspective, social media platforms are often tricky because they are typically owned by a third party that sets rules and regulates what is possible. The third parties also charge for the use of the social media space, making this medium costly. The companies often differentiate between earned media, which is essentially non-paid visibility, and paid media, which refers to paid visibility. In social media, although most word of mouth is organic (that is, stems from the participant interest and spreads around on its own), firms may need to seed content and pay for initial visibility.

One of the greatest challenges in social media is the measurement of outcomes. One central question is to what degree firms can differentiate between traditional marketing, communication, and customer service, and often the difficulty is that in social media, all these three areas come together.29

NOTES

1. According to Boyd and Ellison (2007), social networking sites are sites that ‘allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system’. Boyd, D.M., & Ellison, N.B. (2007) Social network sites: definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13. Retrieved from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol13/issue1/boyd.ellison.html

2. Crowdsourcing entails the engagement of large numbers of individuals to conduct tasks (Howe, 2008), whereas crowd funding refers to the collective actions of people within a network to gather money for a purpose that other people or organizations have defined (Ordanini, 2009). Howe, J. (2008). Crowdsourcing: Why the Power of the Crowd is Driving the Future of Business, New York: Random House. Ordanini, A. (2009). Crowd funding: customers as investors. The Wall Street Journal, 23 March, 3.

3. Kucuk, U.S., & Krishnamurthy, S. (2007) An analysis of consumer power on the Internet. Technovation, 27, 47–56.

4. Lawrence, B., Fournier, S. and Brunel, F. (2013) When companies don’t make the ad: a multi-method inquiry into the differential effectiveness of consumer-generated advertising, Journal of Advertising, 42, 292–307.

5. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/jul/23/united-airlines-guitar-dave-carroll

6. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1201671/Singer-Dave-Carroll-pens-YouTube-hit-United-Airlines-breaks-guitar–shares-plunge-10.html

7. http://www.slideshare.net/rouenbs/netnography-by-joonas-rokka

8. See Huotari, K. (2014) Experientalizing – How C2C communication becomes part of the service experience. The case of live-tweeting and TV viewing. Helsinki: Hanken School of Economics, Finland.

9. http://www.360i.com/work/oreo-super-bowl/

10. Kozinets, R. (1999) E-tribalized marketing? The strategic implications of virtual communities of consumption. European Management Journal, 17, 252–264.

11. Kaplan and Haenlein applied the social presence theory of Short, Williams, & Christie and the media richness theory of Daft & Lengel to classify social media, varying from low media such as blogs, medium level media richness of social networking sites, and high level media richness of virtual social worlds, such as Second Life or the Finnish teenager virtual world Habbo. Kaplan, A.M. and Haenlein, M. (2010) Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53, 59–68.

12. Kaplan and Haenlein (2010).

13. Weinberg, B.D. and Pehlivan, E. (2011). Social spending: managing the social media mix, Business Horizons, 54, 275–282.

14. Porter suggests that communities can be divided into organization and customer communities. Organization-sponsored communities can be divided into commercial, non-profit, and governmental communities. Porter, C.E. (2004) A typology of virtual communities: a multi-disciplinary foundation for future research. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication [online], 10.

15. Tagging refers to the act of putting labels on items in social media, for example people in photographs can be tagged to connect their figure with their Facebook profile.

16. Fournier, S. and Avery, J. (2011) The uninvited brand. Business Horizons, 54, 193–207.

17. See e.g. http://www.ihateryanair.org/; http://www.ihatesbux.com/forum/

18. Gummesson, E. (1991) Marketing orientation revisited: the crucial role of the part time marketer. European Journal of Marketing, 25(2), 60–75.

19. Nelson, P. (1970) Information and consumer behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 78, 311–329.

20. van Doorn, J., Lemon, K.N., Mittal, V., Nass, S., Doreén, P., Pirner, P. and Verhoef, P.C. (2010). Customer engagement behavior: theoretical foundations and research directions. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 253–266.

21. Gummerus, J., Liljander, V., Weman, E. and Pihlström, M. (2012). Customer engagement in a Facebook brand community. Management Research Review, 35(9), 857–877.

22. Kozinets, R.V., Hemetsberger, A., Jensen Schau, H. (2008). The wisdom of consumer crowds: collective Innovation in the age of networked marketing. Journal of Macromarketing, 28(4), 339–354.

23. Muller, A., Hutchins, N. and Pinto, M.C. (2012). Applying open innovation where your company needs it the most. Strategy & Leadership, 40(2), 35–42.

24. Chesbrough, H.W. (2003). A better way to innovate. Harvard Business Review, 81(7), 12–13.

25. Gebauer, J., Füller, J. and Pezzei, R. (2013). The dark and the bright side of co-creation: triggers of member behavior in online innovation communities. Journal of Business Research, 66(9), 1516–1527.

26. Sepp, M., Liljander, V. and Gummerus, J. (2011) Bloggers motivations to produce content – a uses and gratifications theory perspective. Journal of Marketing Management, 27(13–14), 1479–1503.

27. Gwinner, K.P., Gremler, D.D. and Bitner, M.J. (1998) Relational benefits in service industries: the customer’s perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 26(2), 101–114.

28. Shang, R.-A., Chen, Y.-C. and Liao, H.-J. (2006) The value of participation in virtual consumer communities on brand loyalty. Internet Research, 16(4), 398–418.

29. Gummerus et al. 2012.

REFERENCES

Boyd, D.M., and Ellison, N.B. Social network sites: definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 2007, 13.

Chesbrough, H.W. A better way to innovate. Harvard Business Review, 81(7), 2003, 12–13.

Fournier, S. and Avery, J. The uninvited brand. Business Horizons, 54, 2011, 193–207.

Gebauer, J., Füller, J. and Pezzei, R. The dark and the bright side of co-creation: triggers of member behavior in online innovation communities. Journal of Business Research, 66(9), 2013, 1516–1527.

Gummerus, J., Liljander, V., Weman, E. and Pihlström, M. Customer engagement in a Facebook brand community. Management Research Review, 35(9), 2012, 857–877.

Gummesson, E. Marketing orientation revisited: the crucial role of the part time marketer. European Journal of Marketing, 25(2), 1991, 60–75.

Gwinner, K. P., Gremler, D. D. and Bitner, M. J. Relational benefits in service industries: the customer’s perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 26(2), 1998, 101–114.

Howe, J. Crowdsourcing: Why the Power of the Crowd is Driving the Future of Business. New York: Random House, 2008.

http://www.ihateryanair.org/; http://www.ihatesbux.com/forum/

http://www.slideshare.net/rouenbs/netnography-by-joonas-rokka

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/jul/23/united-airlines-guitar-dave-carroll

http://www.360i.com/work/oreo-super-bowl/

Huotari, K. Experientalizing – How C2C Communication Becomes Part of the Service Experience. The Case of Live-Tweeting and TV Viewing. Helsinki: Hanken School of Economics, Finland, 2014.

Kaplan, A.M. and Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53, 2010, 59–68.

Kozinets, R. E-tribalized marketing? The strategic implications of virtual communities of consuption. European Management Journal. 17, 1999, 252–264.

Kozinets, R.V., Hemetsberger, A., Jensen Schau, H. The wisdom of consumer crowds: collective innovation in the age of networked marketing. Journal of Macromarketing, 28(4), 2008, 339–354.

Kucuk, U.S. and Krishnamurthy, S. An analysis of consumer power on the Internet. Technovation, 27, 2007, 47–56.

Lawrence, B., Fournier, S. and Brunel, F. When companies don’t make the ad: a multimethod inquiry into the differential effectiveness of consumer-generated advertising. Journal of Advertising, 42, 2013, 292–307.

Muller, A., Hutchins, N. and Pinto, M.C. Applying open innovation where your company needs it the most. Strategy & Leadership, 40(2), 2012, 35–42.

Nelson, P. Information and consumer behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 78, 1970, 311–329.

Ordanini, A. (2009) Crowd-funding: customers as investors. The Wall Street Journal, 23 March, 3.

Porter, C.E. A typology of virtual communities: a multi-disciplinary foundation for future research. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10, 2004.

Sepp, M., Liljander, V. and Gummerus, J. Bloggers motivations to produce content – a uses and gratifications theory perspective. Journal of Marketing Management, 27(13–14), 2011, 1479–1503.

Shang, R.-A., Chen, Y.-C. and Liao, H.-J. The value of participation in virtual consumer communities on brand loyalty. Internet Research, 16(4), 2006, 398–418.

van Doorn, J., Lemon, K.N., Mittal, V., Nass, S., Doreén, P., Pirner, P. and Verhoef, P.C. Customer engagement behavior: theoretical foundations and research directions. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 2010, 253–266.

Weinberg, B.D. and Pehlivan, E. Social spending: managing the social media mix. Business Horizons, 54, 2011, 275–282.

FURTHER READING

Culnan, M.J., McHugh, P. & Zubillaga, J.I. (2010) How large U.S. companies can use Twitter and other social media to gain business value. MIS Quarterly Executive, 9(4), 243–259.

Grace-Farfaglia, P., Dekkers, A., Sundararajan, B., Peters, L., & Park, S. (2006) Multinational web uses and gratifications: Measuring the social impact of online community participation across national boundaries. Electronic Commerce Research, 6, 75–101.

Gummerus, J., Liljander V. & von Koskull C. (2014) The Role of E-Health Information in the Empowerment of Customers. In Kandampully, J. (ed.) Service Management in Health & Wellness Services. Dubuque, IA, US: Kendall Hunt Publishing Company.

Heinonen K. (2011) Consumer activity in social media: managerial approaches to consumers’ social media behavior. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 10(6), 356–364.

Heller Baird, C. & Parasnis, G. (2011) From social media to social customer relationship management. Strategy & Leadership, 39(5), 30–37.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Malthouse, E.C. Friege, C., Gensler, S., Lobschat, L., Rangaswamy, A. & Skiera, B. (2010) The impact of new media on customer relationships. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 311–330.

Hoffman D.L. & Fodor, M. (2010) Can you measure the ROI of your social media marketing? Sloan Management Review, 52(1), 41–49.

Hoffman, D.L. & Novak T.P. (2012) Toward a deeper understanding of social media. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 26, 69–70.

Hollebeek, L.D., Glynn, M.S. & Brodie R.J. (2014) Consumer brand engagement in social media: conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28(2), 149–165.

Jahn, B. & Kunz, W. (2012) How to transform consumers into fans of your brand. Journal of Service Management, 23(3), 344–361.

Kietzmann J.H., Hermkens K., McCarthy I.P. & Silvestre B.S. (2010) Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Business Horizons, 54(3), 241–251.

Lipsman, A., Mudd, G., Rich, M. & Bruch, S. (2012) The power of ‘Like’: how brands reach (and influence) fans through social-media marketing. Journal of Advertising Research, 52, 40–52.

McQuarrie, E.F., Miller, J. & Phillips, B.J. (2013) The megaphone effect: taste and audience in fashion blogging. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(1), 136–158.

Michaelidou, N., Siamagka N.T. & Christodoulides G. (2011) Usage, barriers and measurement of social media marketing: an exploratory investigation of small and medium B2B brands. Industrial Marketing Management, 40, 1153–1159.

Sashi, C.M. (2012) Customer engagement, buyer-seller relationships, and social media. Management Decision, 50(2), 253–272.

Weinberg, B.D. & Pehlivan, E. (2011) Social spending: managing the social media mix, Business Horizons, 54, 275–282.