Chapter 10

Psychological Adjustments to Your Price

In-a-Rush Tip

In-a-Rush TipBy reaching this chapter in this book you now have:

- A price range that buyers have shown they will pay for a product of roughly your benefits and your negatives.

- Your costs.

- Knowledge that you can make an acceptable profit given the two points.

Chapter 10 is where you will learn to adjust your prices to take advantage of buyer psychology.

Don’t skip this step! Buyers make instinctive judgments about prices based on both constant cultural exposure to numbers and prices and by how our brains are wired. Not paying attention to pricing psychology can cause your product sales to be 10 percent lower, 15 percent, or even worse.

It’s that important.

Understanding “Barriers” in Prices

A key part of brain development is learning how to screen out unnecessary “noise” from our senses. Otherwise we would be paralyzed by all the input coming in every minute.

Native speakers of any language that reads left to right, as ours does, have learned that the numbers on the left side of a number are far more important than the numbers on the right. On the right are cents, or dollars. On the left are thousands, millions, or even billions.

In addition to paying more attention to the leftmost parts of numbers, we have also learned that larger equals bigger.

Together these learned perceptions create artificial barriers in how we see numbers. For example, consider your reaction to each of these two prices:

- $1,000

- $999

If you see them together like this, the effect is diluted. Your left (logical) brain can recognize there is only $1 difference between them. But if you saw only one of these prices, attached to something you wanted, your perception of how expensive the item is would be quite different, depending on which of these prices was attached.

That’s partially because we’ve gone from a three-digit number to a four-digit number.

Staying below Barriers

Direct-mail and Internet marketers have found that crossing the barrier to a larger leftmost number (e.g., from an “8” to a “9”) can cause a drop of 10–15 percent in response.

The largest barriers—with the greatest danger in response fall-off—add an extra digit to the price, as in the above as well as:

- $9.99 to $10.00

- $99 to $100

But you can easily see a 10 percent drop in response by moving from $29 to $30. We’re wired to notice the left-most part of the number. And even though the digits haven’t increased, we have moved from a price of $20-something to $30-something.

This isn’t evil marketers tricking consumers. Every person over the age of consent in the United States knows that $99 is just one dollar different from $100. So why does it work? Because the $99 price allows consumers to “trick” themselves.

Consumers like to feel they are smart shoppers. They like to feel they’re getting a deal. Being able to say they paid $90-something for the product makes them feel better than saying they paid “almost $100.” In fact, if you asked 100 people (who just spent $99.99 for something) what they paid, I’d be surprised if more than one told you $100. Most will tell you “$99” or “$90-something.”

You know—and they know—that $99.99 is virtually the same as $100. But if 10–15 percent fewer customers will buy at $100 as will buy at $99.99, then buyers are telling you something you have to listen to in order to sell. They’re telling you to adjust your price so they can both have what they want and feel like a smart shopper (or at least not feel like a poor shopper).

Increasing Prices up to Barriers

This works the other way as well. It means that prices under the barrier can often be moved up with no drop at all in response, as long as they don’t cross a barrier.

Examples:

- Suppose you’re considering a price of $9.85. There’s a very good chance you could move your price up to $9.95 or $9.99 and not have any drop in response.

- Suppose you’re considering $85. You could almost certainly charge $89 and see little if any dropoff.

- I once consulted for a newsletter publisher who was charging $345/year for a subscription. Lots of other not-exactly competitor newsletters were charging $300-something, including $395. Some were charging in the $400-somethings.

- The publisher had neither enough money nor enough subscribers to really test prices, so I told him to just raise the price to $375. I told him I didn’t think he’d get any dropoff, and he didn’t. So he was pocketing $30 more per subscriber per year with the same number of subscribers.

- This carried some risk, because he passed three smaller barriers, moving from 45 through 55 through 65 up to 75. But my judgment for this industry was that higher $300-something prices were so normal that most companies wouldn’t even notice the jump—as long as the leftmost number stayed the same. That would not necessarily be true in a lot of other industries.

Barrier Price Adjustments for You

Your goal in this chapter is to find the three or four best potential prices for your product—all of which are psychologically smart.

Let’s say your price range from the Narrowing Your Price Range Worksheet in Chapter 7 is $52–$68. Knowing what you now know about barrier prices, what is one number in that range you absolutely must test? Right below the biggest barrier in your range? Correct. It’s $59. So what other prices should you test? The simplest solution is to test the high and the low, so you’d test $52, $59, and $68. However, $68 might not be any different in response from $69, so you might want to test $69 instead of $68.

But it isn’t always that clear a choice.

Suppose your ideal price range is $40–$61. Now what do you test? Here’s what I’d recommend—based solely on barrier pricing psychology:

- $39,

- $49,

- $59, and

- $62

Let me explain why.

If your ideal range starts with a number right on top of a barrier ($40 in this example), you really need to see how much more you could bring in if you dropped below that barrier. If not $39, then at least $39.99. If you can make an acceptable profit at $40, then you can make an acceptable profit at $39.99 as well. And you might have 10–15 percent more units sold!

Why, if your upper number in your range is $61, do I recommend testing $62 instead of $61? Because numbers just over a barrier typically don’t do very well. $60 or $61 will usually pull worse than $62. I don’t have a proven reason why, but I believe at $60 or $61 you can only compare the price to $60. At $62, you can imagine it being a discount from $70, which would mean the product is both higher quality and a good discount.

Most important: You must pick a price to test that is higher than you believe it is possible to get.

If you don’t, you’re an idiot. Just like I was an idiot when I didn’t test high enough prices for my newsletter launch—which resulted in my missing out on $38,000 in profits I could have pocketed.

Be sure to test the high price of your range. And if that high price ends in a 0 or a 1 (as in $60 or $61), make sure to move up to $62 or $64.

Numbers that Say “Discount” to Buyers

There are certain numbers you can use that cause buyers to think your product or service is discounted. And that can be a good thing—or a bad thing—depending on the perceptions you want for your offering.

Pennies in any price over $40 look like a discount price, which buyers in most industries will perceive as meaning the product is a discount-type of product.

The only industry where I have noticed prices like $999.99 on high-quality products is in the consumer electronics industry. In almost all other industries, a price of $999.99 would signal a lower-quality product than one priced at $995.

A “9” on the far right end of a product/service price also signals “discount” to buyers, often with the “discount” label extending to the product’s quality.

Examples:

- The consumer health newsletter industry has a lot of offerings at $19.99, $29.99, and $39.99. Harvard Medical School publishes a number of consumer health newsletters. Their prices are $22, $24, and $28. See how much classier their image is—just from not ending in a “9” or having pennies in their prices?

- High-end restaurants predominantly use a “0” or a “5” as the farthest-right digit of their menu prices, while low-end fast-food restaurants primarily use a “9.” In a number of studies, Naipaul and Parsa (2001) found consumer reaction to menus from fictitious restaurants could be influenced by the rightmost digit of the prices. Subjects rated menus with prices ending in a “0” as higher in quality than those with menu prices ending in a “9.”

Another reason I advise against having pennies in any price over $40 for any product other than those with a penetration price positioning is that it makes the price look longer. Remember from “barrier pricing” previously that the longer the number, the bigger we perceive it.

Test Your Knowledge!

Pick the best price examples:

- $22.99 versus $24 for a prestige product

- $24 reinforces your prestige positioning and will likely do better or equal to $22.99.

- $20.95 versus $22.95 for a competitive product

- Prices just above a barrier number ($20) are likely to do less well than prices farther above. It’s likely that $22.95 will pull more or at least the same number of orders.

- $52.99 versus $53

- Because of the pennies, $52.99 looks bigger and may draw fewer orders than $53.

- The only instance where I would recommend the $52.99 price here is where you’re trying hard to be perceived as the biggest discounter in the industry. If having the lowest price is your positioning, then go with the pennies.

- $19.99 versus $20

- This is a trick choice. The pennies may cause you to believe $19.99 would be perceived bigger, but this crosses a barrier where the leftmost number changes (from a “1” to a “2”). In this case the barrier crossing is more important than the pennies. $20 would probably pull 5–10 percent worse.

Visually Appealing Prices

If you have a shockingly low price, you want it to stand out dramatically. You’ll put it in larger type and bold. You’ll feature it.

Any other price should not stand out. You want it to go down smoothly, like syrup—mildly pleasing, nothing shocking, nothing that causes the swallower to react with a frown or (worst of all!) choking.

For example, there is research on using a “7” in your prices; typically it can raise response rates. If you look at most magazine and newsletter subscription prices you’ll see most of them end in a “7” or at least include a “7.” That’s because publications do a lot of price testing and they have found buyer preference for a “7” to be a fact. (You can see specific research on this in my Pricing Psychology Report book at PricingPsychology.com.)

Some people knowing this have taken it to extremes. They figure if one “7” is great, then more “7s” would be even better.

Yet suppose you were considering products with the following prices:

- $7.77, or

- $777

Seeing prices like these is likely to stop you in your tracks and make you focus on the price. You might even frown in puzzlement. Both of these are very bad responses to elicit from your potential buyers.

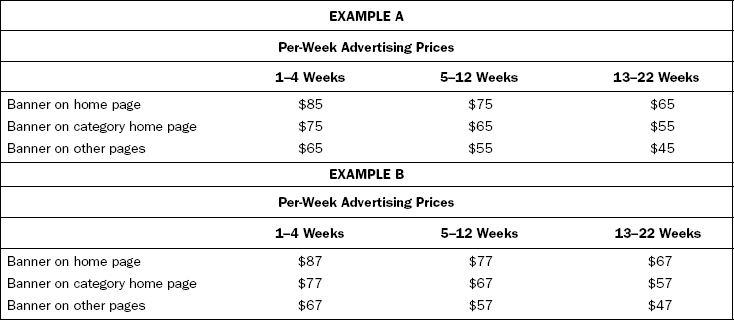

I recently did pricing for an online startup where the prices varied by frequency, so you had a table display. The client had read my Pricing Psychology Report and wondered why I didn’t have “7s” in all the prices. I’ve created phony charts here to show you what I mean, without showing you the client’s actual prices or categories. Consider your reaction if you saw a pricing table like one of the two in Exhibit 10.1.

EXHIBIT 10.1 PERCEPTIONS OF MULTIPLE-PRICE CHARTS

Example A looks like what you’d expect to see. Example B will likely cause you to take a second look at the prices and wonder what is going on with all the “7s.” It’s not what you’d normally see, so you’ll wonder about it.

Buyers wondering about your prices is a bad thing. Something this unusual will cause many of your buyers to wonder if you’re trying to “game” them. If they even consider that, your pricing strategy has failed.

People who think pricing is unfair have been known to refuse to buy something they really wanted just because of it. These same people get angry enough to tell others. For a great book on this topic, check out The Price Is Wrong by Sarah Maxwell.

Moral of the story: Don’t make your prices look “strange.”

Selling to Businesses

All this price psychology applies to B2B (selling to businesses) as well as B2C (selling to consumers). After all, businesses are managed by people, and all people want to feel like smart buyers.

Let’s say you’re pricing a consulting service, and you feel the correct market price is somewhere around $20,000. Let’s look at some possible prices you could charge:

- $20,000

- Two problems with this number: It moves the left number from 1 to 2, and it’s right on top of the barrier. (See the earlier “Barrier Price Adjustments for You” section.)

- $19,999

- The problem with this number is it sounds like a discount shop—where the buyer is risking low-quality work.

- $19,750

- This is the number I would recommend. It’s below a big barrier, doesn’t have the “99” discount taint, and it includes a “7.” (See the “Visually Appealing Prices” section.)

- $22,275

- This is another price to consider. If the last time you quoted a price, you got the job without much discussion about the price, then you are underpriced. This is a good price to quote because it is not on top of a barrier, and it looks like you’re not rounding up to gouge someone. And it has a “7.”

Learn More about Thresholds

Every human sense has limits. An absolute threshold marks the divider between response and no response. For example, the absolute threshold of sound humans can hear differs from that for dogs. JND stands for “just noticeable difference” and refers to our ability (or lack of one) to differentiate between small changes.

For example, a computer putting out a specific frequency note can go up or down in tone a few steps before it is noticeable to the human ear. So research focuses on how much of a change is required before it is “noticeable.”

This research most often informs product-size decisions. Here’s an example:

Suppose you make M&Ms–type candy, and your biggest selling package sells for $.99 for 2 ounces. You have tested and tested higher prices, but sales take a nosedive when you go to $1.00 or more. Yet your costs have gone up and your CEO is demanding you stop the drop in profits.

What do you do? You could reduce the ounces of candy in the bag. But, using the insights gained from JND threshold research, you want to make the reduction not noticeable. You will list the correct (lower) ounces on the new bag, but you’re hoping someone who picks up a new bag won’t suddenly look at it and think it feels light. It takes some testing. What’s the correct weight? 1.9 ounces? 1.8? The yogurt industry has used this tactic, shrinking individual containers substantially.

But at some point this will no longer work. After all, a 2-ounce yogurt would be ridiculous, as would a fingernail-sized candy bar.

Suppose you don’t believe you can go any smaller in what you offer. Your only way to increase profits at that point is to raise the price—and offer a bigger bag. But here you want JND to work the opposite direction. You want to give enough more product in the bag that consumers will notice the change (but add no more than needed!).

So, in this situation, you might raise your price to $1.25, add as many candies to the bag as needed for it to be noticeable, and have an “X% more!” or other message on the bag itself to be sure it’s noticed.

Threshold research also suggests that there are price points both too high and too low to be acceptable to consumers (e.g., Fouilhe, 1970; Monroe, 1971a).

Gabor and Granger (1966) found absolute price thresholds, high and low, for five common products. They also found evidence suggesting low prices were perceived more negatively to high-income groups than high prices were perceived negatively to low-income groups.

Zaichkowsky (1985) showed that high-product-involvement consumers are less likely to risk a low-priced option.

Learn More about the Effect of Numbers

There is some odd research in psychology about the ability of random numbers to change what people say they will pay in prices. It’s the “anchoring and adjusting” aspect of prospect theory first identified by Tversky and Kahneman (1974).

They found that a number derived from spinning a wheel would nevertheless serve as an anchor when subjects were asked for a number for something completely different. Others also found this.

Ariely, Loewenstein, and Prelec (2003) replicated this type of study by showing students six products, with no indication as to price. (The products each had a retail value of about $70.) Students were then asked if they would buy each for the last two digits of their social security numbers, translated into dollars. After giving an accept or reject response to each, students were then asked to state the highest price they would be willing to pay for each. The impact of the social security numbers on the subsequent price students were willing to pay was significant for all six products. In fact, those subjects with the highest last two digits were willing to pay three times what subjects with the lowest two digits would pay.

Additional experiments by the authors demonstrate what they call “coherent arbitrariness.” They show that consumers respond appropriately to price changes that are called to their attention (coherent), but their initial anchors can be arbitrarily derived from exposure to meaningless numbers.

Wansink, Kent, and Hoch (1998) used this theory to explain consumer purchases of multiple units, where the price of a single unit is the anchor. They found that usage of a high anchor (e.g., “Limit 12 to a Person”) can increase purchase quantities even where there is no discount given for the additional purchases.