Chapter 15

Pricing New Products/Services, Part 2

Competing with Established Brands

In-a-Rush Tip

In-a-Rush TipWhen Your Competitors Are Established Brands

Unfortunately, new brands usually enter markets where they must compete with established brands. That conveys a whole list (following) of advantages for the established brands and only a couple of advantages for the unknown brands.

Established brands are said to have “equity” in their brand name. One of the better definitions of brand equity is that it represents the difference in consumer response to marketing activity for one brand over another, or over an unknown brand (Keller, 1993; Hoeffler and Keller, 2003).

That difference can be either positive or negative, with the latter leading to negative brand equity.

Following are itemized the many advantages known brands command. It is critical to know what these are before deciding on the price for your new brand, because they affect how consumers will react to your brand and price.

Advantages for Known Brands

Known (and respected) brands command a large number of advantages over unknown brands. They include the following:

Increased Learning of New Content

When buyers recognize a brand, they are more likely to learn about new products from that brand. Johnson and Russo (1984) found increased learning of new features and new ad copy for the familiar brand.

This means as a new brand your ads touting your better features (or price) will have to be more noticeable than those for established brands.

More Likely to Consider the Brand

We’re all lazy. When we decide to buy a new product, very few of us consider all possible brands. Simonson, Huber, and Payne (1988) found that consumers will first focus on the most attractive (known) brands and only later consider lesser or unknown brands.

Be wary of research that appears to contradict these findings. The researchers found this process exists only in making a choice, not when asked to rank brands. If research asks consumers to rank brands in a field, consumers first consider moderately attractive or second-tier brands. Thus ranking research will overestimate the attention given to mid-level brands.

The only ways to somewhat alleviate this problem are to create more noticeable promotions and to be extremely clear and on message as to your benefits over established products/services.

Reduced Search Time

Because we’re all lazy, that means we want to spend less time researching the quality of our choices. For those seeking quality merchandise, Dodds, Monroe, and Grewal (1991) found that a brand name, a high price, and availability in a quality retail store all communicate quality to consumers. These days another quality verifier is the customer reviews on web sites. All these quality cues can reduce the amount of search consumers feel is necessary before buying.

As a new brand, this means if you can match two or three of the four, consumers will be reassured of your quality—even without the recognized brand name.

Increased Attention

Tellis (1988) found that consumers pay more attention to messages from preferred brands, which leads to increased responsiveness to those brands. Again, it shows messages from new brands need to stand out better just to get noticed.

Focal Brands

When we compare a group of brands, we typical start with a “focal” brand—a brand to which we compare the others. An established brand, with higher awareness and feature recall, is more likely to be the focal brand. And a focal brand is more attractive than the others, unless the others give powerful reasons to switch focus. Dhar and Simonson (1992) did some interesting research in this area.

There’s nothing really a new brand can do here. It’s a problem for second-tier established brands as well; it’s one of the benefits of being the leading brand in a category.

Positive Attitude Carryover

Established brands carry a positive attitude that affects consumer response to them. A number of research studies have backed up this finding, including the following.

Affects Reaction to Ads

Raj and Stoner (1996) showed consumers mocked-up ads for State Farm and an unknown competitor, as well as for Kinko’s and an unknown competitor. When asked their likelihood to switch from a current provider to either of the others, the scores were significantly higher for the known brands:

Affects Both Quality Ratings and Purchase Intentions

A number of research studies show that a brand name can be seen as a “guarantor” of quality. In fact, in most cases, consumers will choose a brand name as being a better indicator of quality than is a higher price (Monroe, 1973).

I and Dr. Drozdenko (2004) studied known brands versus unknown brands in five product categories. We found the known brand in each category had both higher quality and higher likelihood-to-buy ratings.

Dawar and Parker (1994) found brand name signals to be the most important factor for consumers in determining product quality. Price and physical appearance were the next most important, followed by retailer reputation.

So what does this mean for new products/services where quality is an important selection criterion for buyers? It means you:

- Are at a disadvantage (no surprise here!)

- Need to use the remaining tools at your disposal very carefully to project the quality image you’re seeking

- Your price needs to say “quality.”

- Your physical appearance of the product (or the service environment) is even more important than for established brands.

- Your actual quality will be critical, if consumers post reviews of products in your category.

Affects How Buyers React to Humor(!)

As a crazy example of just how powerful brand reactions can be, Chattopadhyay and Basu (1990) found that humorous ads are less effective for unknown brands!

They found that new product/service ads require greater attention and learning from buyers, and the humor in those ads draws attention away from the product. That’s not a problem if buyers already know about the brand, but it is a big problem when it causes buyers to skip paying needed attention to learning about a new product/service.

What can you do? Save the humor in your promotions until buyers are aware of your product/service brand.

Risk Avoidance

If you’re launching a new product/service, there are some very disturbing research results in the area of risk avoidance—especially for “performance risk.” Performance risk is the risk that what we buy won’t work (or won’t work well) and we might be stuck with a poor product.

We’re not surprised that consumer perceptions of the performance risk of a product from an unknown brand are greater than for a known brand (Grewal, Gotlieb, and Marmorstein, 1994). That makes sense.

However, Muthukrishnam (1995) pushed this further by studying an unknown brand compared to a known brand that was markedly inferior. Here are the disheartening results:

- When no product trial was available, 65 percent of the subjects chose the known, inferior brand over the unknown brand.

- When a free trial was offered, 39 percent still chose the known and inferior brand.

- Half of those who chose the known brand were extremely confident that it was superior—despite very clear indications it was inferior.

- Even worse—38 percent of those who chose the known brand agreed that the unknown brand was superior, demonstrating a strong risk aversion by going with the known even in the face of superior attributes.

What can entrepreneurs do in the face of such disheartening results? Here are some suggestions:

- Offer some sort of free trial if at all possible (it almost doubled the number who would try the new brand).

- Offer the strongest guarantee you can as to performance. Let buyers know how easy it would be to return the product/cancel the service if they weren’t 100 percent satisfied.

- Offer extensive details on your quality and on the specifics of what you offer.

- If you can, get other people to verify how much better your product/service is than the competition, as in testimonials. Just note that believable testimonials contain the full name of the recommender.

- When businesspeople are doing the recommending, a link to their web sites is a gold standard of believability. And it increases the chance of getting the testimonial, as it would be an incoming link that could help their site’s Google ranking.

- Individuals as testimonial providers are less believable, so be sure to add specifics in the testimonial to increase believability.

Price Premiums for Known Brands

Top-tier brands can usually command a price premium over their competitors. The size of the brand advantage for Hewlett Packard laser printers was researched by Crowley and Zajas (1996). They noted that Hewlett Packard typically maintained a 10–20 percent price premium over competitors, despite a market share of over 60 percent. They also noted that in 1990–1991, low-priced competitors cut their prices, which caused the price premium for Hewlett Packard to climb over 20 percent, at which point Hewlett Packard lost 13 points of market share.

So while consumers are willing to pay more for quality brands, there’s a limit to the size of that premium—at least for some buyers.

Brand-loyal customers have a wider range of acceptable prices (Kalyanaram and Little, 1994). These researchers argue that brand-loyal customers believe whatever their preferred brand charges is “normal.” They then judge other brand prices by their difference (up or down) from whatever their preferred brand’s price is.

Following is some research I did with Dr. Ron Drozdenko to try to uncover just how substantial a benefit a name brand has over an unknown brand—particularly at different price levels for the unknown brand.

We found the difference in buyers willing to buy a new brand dropped 17 percent (across four product categories) when an established brand was available. See Exhibit 15.1. When we looked at it by product category, entering a market with a name brand competitor caused anywhere from a 10–20 percent decline in intent-to-buy.

EXHIBIT 15.1 Name-Brand Equity Over Unknown Brands

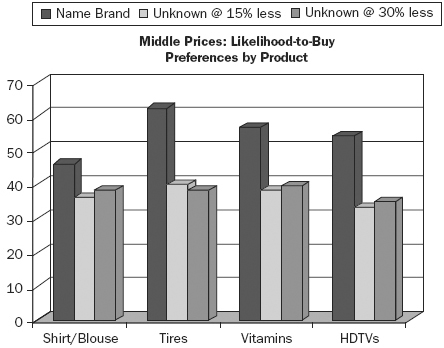

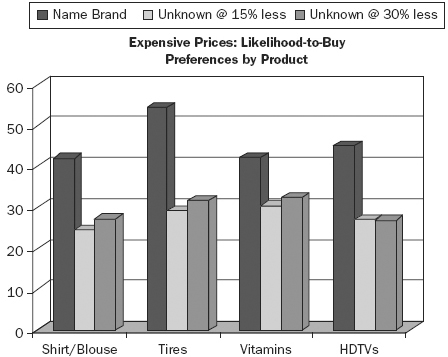

We were also interested in any differences depending on what price positioning the new brand had. Did it compete against bargain name brands? Middle-of-the-road name brands? Premium name brands?

We found for a shirt/blouse and for HDTVs, an unknown brand came closer in selection to a name in the bargain-price than in higher-price categories. For vitamins, it was the opposite: It was easier for the unknown brand to compete in the premium categories.

Exhibits 15.2, 15.3, and 15.4 show the details of what we found.

EXHIBIT 15.2 Bargain Prices

EXHIBIT 15.3 Middle Prices

EXHIBIT 15.4 Expensive Prices

In a wild leap of hopeful thinking on my part, we also looked at how a higher-priced unknown brand would do against a 15 percent lower priced brand name. (I’d found just one research study to suggest there might be positive news in this scenario.)

Unfortunately, hope wasn’t supported by the facts, although shirts/blouses and vitamins had a smaller difference between the two than the other two product categories. See Exhibit 15.5.

EXHIBIT 15.5 Preference for Name Brand over 15% Higher-Priced Unknown Brand by Product

The difference applied across all three price position categories, although a 15 percent higher-priced product competing against bargain-positioned name brands had a better chance of success than it did in the higher price positions. (See Exhibit 15.6.)

EXHIBIT 15.6 Preference for Name Brand over 15% Higher-Priced Unknown Brand by Category Price Level

Discounting Differences

A large number of research studies show that price promotions (discounts) from top-tier brands attract purchasers of lower-level brands. Those studies also show the reverse is not true: Lower-level brand promotions do not equally attract purchasers of top-tier brands (Agrawal, 1996; Sivakumar and Raj, 1997; Park and Srinivasan, 1994; Blattberg and Wisniewski, 1989).

Unknown brands need to be wary of discounts. For example, Moore and Olshavsky (1989) found a positive buyer response to all levels of discounts for name brands, but found a negative response at the highest level (75 percent) for unknown brands.

Advantages for Unknown Brands (Yes, There Are a Few!)

There are a few positives for unknown brands, although many of them are just groups that are more likely to be adventurous and try a new brand.

Look for “Innovators”

Just as there is a group of “bargain hunters” who love the thrill of finding a deal, there is also a group of “innovators” who are thrilled by finding something new.

The only problem is there are fewer innovators (estimated at 2–3 percent of the population) than bargain shoppers. Nevertheless, this group does exist and you can profit if you can identify and promote to them when you launch a new product/service.

Of course, that assumes your product/service is actually new, not just the same old thing everyone else is selling—but a new brand name. This group will not be impressed by something “new” that really isn’t.

Finding innovators is typically a problem. In some markets it’s almost impossible. In others, the innovators are professionals who will expect payment for using your products and letting others know it. (Think snowboards, tennis racquets, etc.)

One way to search for them is to rent mailing lists of people who bought the last new thing—at the start. For example, let’s say your new product is product “C,” which came after and improved upon products “A” and “B” in your industry. Try to find a direct mail list of people who bought “B” when it first launched.

People (latest estimates are at 500,000 or so) who promote for buzz marketing type firms are also people who want to know what’s new. These firms typically don’t pay money to their promoters. Instead they get free samples of the latest new things. If your product is national and you have the budget, you might profit from accessing their promoters.

Look for the Most Knowledgeable Buyers

Buyers most knowledgeable about products or services in your industry are significantly less likely to be influenced by brand image (Biswas and Sherrell, 1993). These buyers are also highly confident in their ability to estimate the appropriate price for an offering based on its features relative to competitors. So if your product is priced appropriately for its features, as you accomplished in Chapter 6, this group will look past established brands and give you a fair opportunity.

Target Low Income/Education or High Income/Education

New brands may have more chance when aimed at low-income and/or education segments, or at high-income and education segments.

Chance and French (1972) surveyed consumers about their willingness to switch grocery brands for a lower price. They first asked subjects for brand preferences in seven different product types. Then they asked how big a price break they would want to switch to a different brand. The most interesting result from this study was a U-shaped response over both income categories and education.

The lowest and the highest income and education groups were more willing to switch for a much smaller price break than those in the middle income or education groups. Further, the education effect persisted independent of income levels.

The raises the question of whether middle income and middle education groups are more conservative and more brand-dependent.

Target Infrequent Buyers

While we all want to sell to heavy purchasers in our categories, some research suggests that infrequent buyers might be a better target when your brand is new. For example, Gonul, Leszczyc, and Sugawara (1996) found that the less frequently a household purchases ketchup, the more likely it will switch brands.

Coupons Work—with Some Dangers!

The method you use to cause brand switching can affect both the number of switchers and subsequent sales.

Media-distributed coupons generated the most brand switching, compared to cents-off deals and package coupons (Dodson, Tybout, and Sternthal, 1978).

However, when these coupons are withdrawn, not only do the switchers leave, but significantly more of the brand-loyal buyers also leave! Of course, as a new brand you don’t have brand-loyal buyers, so this is more a danger to worry about once you are more established.

The authors recommend cents-off marked deals instead. Cents-off deals do cause brand switching (although less than media-distributed coupons) without the dramatic falloff in repeat sales.

Really High Prices Are More Believable (!)

There’s a lot of research on what is termed “implausible external reference prices” that is intriguing when it comes to known versus unknown brands.

When faced with startling high (implausible) prices, consumers tend to discount them. This is especially apparent when you see a “Was $1,000/Now $500” type of promotion. The $1,000 is discounted as not believable.

But consumers are less likely to discount such a price for an unfamiliar brand than they are for a known brand (Biswas and Blair, 1991). The researchers conclude that consumers heavily discount an implausible price for a familiar brand, to bring it closer to their (more strongly held) prior estimates. Thus, implausibly high advertised prices are more believable when paired with an unknown brand.

Even more interesting, they found that an implausibly high price resulted in higher shopping intention (intent-to-buy) for unfamiliar than for familiar brands.

This indicates a potential high-end price positioning niche for unknown brands. I’ve done some preliminary research in this area and found unknown brands priced higher than established brands do not attract more buyers than the known brand. But there is some preliminary evidence that the penalty you pay for being unknown is less in the highest price positions than in middle to lower ones.

What Causes Customers to Switch to a New Brand?

A new brand almost always requires a buyer to switch from an established brand in order to make a sale. For that reason, we can learn from research on brand switching—even though much of the research is about switching from one known brand to another.

The only time new brands don’t require switching is when your new brand creates a “blue ocean” where there are no competitors. For example, [yellow tail] wines created a strategy that caused it to appeal to people who were not previously wine drinkers. For a great read and lots of ideas, I definitely recommend you read Kim and Mauborgne’s book Blue Ocean Strategy.

Factors for Switching

A lower price isn’t the only reason for switching to a new brand. Dr. Drozdenko and I in 2003 examined many reasons for switching from a preferred brand to a new brand. Exhibit 15.7 shows what we found when we looked at toothpaste.

EXHIBIT 15.7 CAUSES OF BRAND SWITCHING

| Factors Causing a Switch to an Unknown Toothpaste Brand | Mean |

| Try it free offer | 7.545 |

| Am. Dental Assn. recommends it | 5.969 |

| Save 30% over your regular brand | 5.735 |

| Ranked #1 by Consumer Reports | 4.980 |

| Latest scientific advance | 4.876 |

| Research study says it’s the best | 4.848 |

| All new! | 4.743 |

| Your brand had a recall (now corrected) | 4.339 |

| Save 15% over your regular brand | 4.234 |

| Better for the environment than your brand | 3.896 |

| Endorsement by a celebrity | 3.697 |

We found differences in younger consumers compared to older. Younger buyers were more likely overall to be willing to switch. And they were especially likely to switch if:

- A new offer is available.

- Their preferred brand was once recalled.

- A new brand has extra features.

- Their preferred brand comes out with an ad they hate.

We also found females were more likely to switch than males after seeing an ad for another product.

Likelihood to Switch

When a customer enters a store intending to buy one brand, what is the likelihood of that person switching brands? There is a fair amount of research on grocery shopping and brand switching. For example, Cavallo and Temares (1969) found 18–21 percent of grocery shoppers switched brands inside the store. They further broke it out as follows:

- Buyers of canned and frozen vegetables switched 21 percent of the time.

- Buyers of soaps/detergents switched 19 percent of the time.

- Those buying beverages switched 18 percent of the time.

Convenience

Convenience also plays a role in causing brand switching. Cavallo and Temares also found that 19 percent of shoppers who enter a store expecting to buy a preferred brand actually walk out with a different brand.

They also asked shoppers what they would do if their preferred brand was not in the store. Given this scenario, 59 percent of all subjects said they would purchase another brand.

Of that 59 percent, however, 23 percent of these buyers had rated the strength of their brand preference as moderate to poor (“4” to “7” on a seven-point scale where “1” is the strongest preference).

Of those who gave their brand preference the highest rating, just 31percent said they would buy another brand if theirs was not in the store.

Still, that means 31 percent of the most loyal buyers of a brand are willing to switch for convenience.

Doing What Others Do

Ever wonder why the heck advertisements state their popularity? “We’re #1—more buyers choose us than any other brand.”

If your answer (like mine) to that is “So what? Who cares?” you’ll be surprised to know that research shows a lot of people care.

Wanting to fit in with others can cause buyers to switch to more “popular” brands. For example, Weber and Hansen (1972) found 46 percent of housewives would switch from their preferred brands to brands they were told were the preferred brands of other housewives in the study.

This willingness to switch was the same over six different product categories, including food items and toothpaste.

Regret and Switching

When people chose products/services under uncertainty (such as when it’s an unfamiliar brand), regret theory says they will try to anticipate possible regret and act to avoid it (Loomes and Sugden, 1982).

One problem for entrepreneurs is that switching produces more regret than staying with a current brand, because the status quo is more “normal” (Kahneman and Miller, 1986).

The reasons for a buyer switching brands affected regret and in some cases reversed the normal finding of more regret for switching than for not. If prior experiences with the current brand were bad, consumers felt less regret if they switched than if they didn’t. And this was true even if the new brand also proved unsatisfactory (Inman and Zeelenberg, 2002).

What Happens after Buyers Switch?

Assuming you can get customers to try your new brand, how likely are you to hold onto them? Lawrence (1969) looked at grocery scanner data for toothpaste purchases over time. Here are some of his findings:

- Consumers who bought the same brand at least five times in one year and then switched

- 31 percent reverted back to the first brand after a single switch.

- 43 percent reverted back if they had bought the first brand 10 or more times.

- 22 percent of the switchers became vacillators, equally likely to buy the original brand or the second brand.

- 12–14 percent became loyal buyers of the new brand.

Lawrence also found that switching once seems to set up a brand-switching frenzy in some consumers, who then go on to try yet a third brand. They are:

- 35 percent of those who previously had medium loyalty to the first brand

- 21 percent of those who had previously bought the first brand more than 10 times consecutively

Did the switching reason affect whether or not the buyer developed a loyalty to the new brand? A price promotion was involved in:

- 10–20 percent of those who became no longer loyal to the first brand

- 37 percent of the switchers who then reverted back to the first brand

Shocking Findings on Brand Names

If you ever have the time for a trip into LaLa Land, you might want to research “false fame” when it comes to brand names.

Apparently, it is very important that consumers believe they recognize your brand name, even if they don’t. Holden and Vanhuele (1999) found that merely hearing fictitious brand names in a product category—for example, being told these names were being considered for a new product—resulted a day (or seven days) later to subjects being more than twice as likely to list those brands as established compared to fictitious names that were not previously mentioned.

This is important because familiar brands tend to be favored in choice situations. One of the key aspects of this research is that consumers will remember the brand names, but not the situation within which they heard the brand name; else they would remember that those brands were nonexistent.

The same results have been found when researchers have someone memorize a list of names as a memory test. A week after the memory test, subjects are more likely to “recognize” names on that list and believe them to be established brands.

Baker (1999) found that mere exposure to brand names can have strong effects on which brand will be chosen. Thus a promoted name will cause a new or low-share product to be preferred over other new or low-share equivalent-attribute brands.

So What Does it all Mean for Pricing a New Product/Service?

After reading this chapter, doesn’t it seem almost miraculous that new brands can enter the market and succeed? Yet they can and do. And you can, too.

I believe the major factor in success comes down to positioning. Here are some key questions to ask to best determine your positioning, and therefore your price:

Based on all this research, it appears your best positioning strategy is competitive, anywhere from low to high competitive. You’ll need the extra profits per unit to differentiate your product/service in some manner that matters to the buyer. This could be through additional features, easier payment options, or a psychological positioning (e.g., your product is more appealing to young trendsetters) that will require extensive promotional efforts.