3

Risks and Issues of the Sharing Economy

The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.

Martin Luther King

3.1. Introduction

The sharing economy is at the heart of scientific, political and social debates. Adopting a spectator attitude and suffering the consequences of this new economic model is a great risk for companies.

How can we resist this digital revolution?

Indeed, Pascal Terrasse nicknames it “the third industrial and digital revolution”, and he adds that it will not take effect in companies.

The uberization phenomenon is the main wave to be feared. This concept is a new term which stems from the name of the company called Uber, which uses digital platforms, specifically for car transport services.

This new economic formula is major competition for the traditional economy. The novelty of this phenomenon lies in the change that has particularly affected the supply and distribution channel.

The sharing economy is also disruptive, as a small company with modest resources has the ability to destabilize the market for high-profile companies.

This is a transitional and decisive phase that offers challenges for companies that will either be able to jump on the “bandwagon” or will not dare to take the plunge and embark on this digital adventure. So, what are the challenges of the collaborative economy? Is it flexible enough to organize itself with other existing or emerging forms of economy?

The collaborative or sharing economy adheres to sustainable development: it relates to the issues of sustainability of the economy, the achievement of social well-being and the preservation of nature, and must be cross-functional.

3.2. Uberization: a white grain or just a summer breeze?

As an economic model, the sharing economy raises some concerns about the economic and social impacts it generates. It presents risks for competition and for the various stakeholders. The first impact that observers fear is uberization, to such an extent that well-established companies are afraid to wake up one morning and discover their activities have disappeared (Lévy in (Raimbault and Vétois 2017)).

This fear is legitimate, because it turns out that it is impossible to fight against the various technological, organizational or service-oriented innovations that are commonly called “disruptions” (Raimbault and Vétois 2017). Raimbault adds that this concept is based on Schumpeter’s concept of “creative destruction”.

What does “uberization” mean? The selected definition was based on two visions: the advent of Uber’s business model and the “disruption of traditional industries through innovation”. It should be noted that there are disparities in the conceptualization of uberization, with each author approaching it according to his or her approach.

Some simply consider it as Uber’s business model, others think it is a disruption of conventional models, the latter retain both elements (Lechien and Tinel 2016).

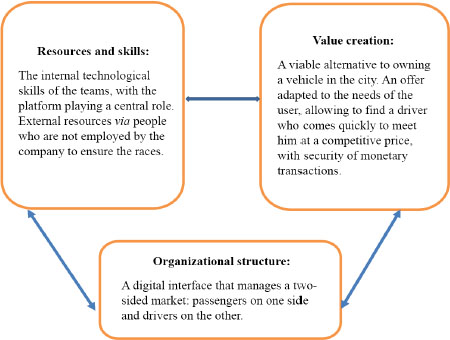

Generally, the platform business model is based on resources and skills, the value proposition and the revenue model. Uber’s model (see Figure 3.1), which is one aspect of the “uberization” definition, has the same key component, which is the use of platforms.

Figure 3.1. Uber’s business model (Diridollou et al. 2016). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/sedkaoui/economy.zip

As for the characteristics of Uber, Brousseau and Penard (2007) propose three aspects from the existing literature:

- – the first aspect: from this perspective, digital networks are mainly understood as markets where supply must meet demand. The performance of transactions between “suppliers” and “consumers” (of functions) requires specific resources in order to solve a set of problems, such as transactional difficulties (matching supply and demand, secure transactions, risk management, etc.). From this point of view, they rely on their ability to organize transactions between both sides of the “market”, in order to reduce costs or make transactions more efficient;

- – the second aspect involves the economic elements of assembly itself and focuses on what we call “assembly costs”. From this point of view, digital networks are generally considered to be production networks in which production resources (the “features”) are combined (assembled) in order to produce a result that can be useful to users in producing alternative methods of combining resources, resulting in compromises between assembly cost levels, the ability to meet users’ needs and the value of consumers as a reward for their efforts;

- – the third aspect involves the economic elements of knowledge management and emphasizes the effectiveness with which information generated by users of digital goods is used to improve services and innovate. From this point of view, digital networks are generally understood as tools for sharing information and knowledge. Alternative ways of doing this have an impact on the effectiveness of collective accumulation and creation of knowledge, including influencing individual incentives to share information with others, the ability to retrieve information that is relevant to each innovator and the dissemination of knowledge (which is a public benefit).

“Change before you have to”1, a quote that resonates particularly in the current context, marked by a major change in the economic model (Jacquet 2017). The advent of new companies without “any reputation” on the market has upset the stability of large companies by putting them to shame.

These start-ups have freed themselves from the enslavement of the traditional industrial model and have found their way through innovation:

Indeed, Facebook is a billionaire and doesn’t generate any content, Airbnb is growing everywhere but doesn’t own any rooms, Alibaba is the largest retailer in the world yet has no stores. (Jacquet 2017)

All these recent companies have taken the opposite direction from the classic business model that has developed in the last millennium. They also have one thing in common: “They have caused real strategic “disruptions” by redefining the way their sector operates” (Jacquet 2017).

3.3. The sharing economy: a disruptive model

Companies are constrained into reviewing their strategies by taking new data into account, especially those related to digital platform technology. Innovations in this field are “a result and a global and cross-functional process, which is nurtured at all stages by multiple sources” (Schaefer 2014).

They have reversed the relationship between producer and consumer, and have changed the very meaning of consumer satisfaction to the extent that the consumer’s main concern is no longer the possession of a good, but rather its use. This strategic revolution has been accompanied by new concepts, such as “disruption”.

Literally, “disruption” means a rupture or break with a habit or activity that has been practiced for a long time. This break is attributed to “radical and architectural” innovation according to Abernathy and Clark (1993) Benavent (2017). This concept has thus been borrowed by the economy to refer to the functioning of certain companies that are in full expansion after a change in their strategy, such as BlaBlaCar, Airbnb and Uber (Jacquet 2017).

It is a transformation of economic systems that has been well established for more than a century, shaken by multi-dimensional innovation, “as was the case with photography, where digital technology broke both a production model based on chemistry and a mass distribution model through the animation of a vast sales and service network” (Benavent 2017).

Referred to as “disruptive innovation” in the book by Clay Christensen et al. in 2015, the concept of disruption has been defined as a disruption that affects businesses. Furthermore:

[It] describes a process by which a small company with fewer resources is able to successfully challenge established companies. More specifically, traditional operators, focusing on improving their products and services for their most demanding (and usually most profitable) customers, exceed the needs of some segments and ignore the needs of others. Incoming disruptive members start by targeting neglected segments and adopting more appropriate functionality, often at a lower price. Owners, pursuing higher profitability in more demanding segments, tend not to react vigorously. The incoming members then move to the high-end, providing the performance that traditional customers demand, while preserving the advantages that have led to their anticipated success. When major customers start to adopt the offers from new incoming members in volume, disruption has occurred. (Christensen et al. 2015)

Thus, the theory of disruptive innovation has proved to be a powerful way of thinking about innovation-induced growth, and companies that do not sense the refreshing change will be swept away by the wave of innovation, especially technological innovation.

Although disruption is induced by the prowess of digital technology, Christensen’s definition refers to three characteristics, according to Benavent (2017). New entrants, despite their small size, are a source of concern for companies with large resources. The disruption may also stem from the failure of the company’s monitoring activity, which failed to anticipate developments and innovations.

It can also result from the organizational system, when structural and behavioral change is expensive. Thus, the following question can be asked: to what extent can an innovation in a company become a disruptive innovation?

In this context, Christensen wonders whether Uber really is a disruptive innovation.

The answer to these questions can be found in the definition of the term uberization. The latter does not yet have a consensus, each definition addresses an aspect of this new concept.

The definitions cited above are similar on two levels: the upheaval caused by the advent of digital platforms in the business world of companies and the tensions in the relationship between these companies and the platforms.

Thus, if we use the following definition of uberization, it contains the answer to the previous questions. Indeed:

The uberization of an industry can be defined as a phenomenon with the following two characteristics: the entry of a P2P platform into an existing industry, as well as the disruption of power relations between established companies in that industry and the P2P platform. The uberization of the economy therefore corresponds to the emergence of this phenomenon in more and more sectors. (Lechien and Tinel 2016)

However, Christensen et al. (2015) argue that Uber can in no way represent a disruptive innovation, even though it is considered as such. Their arguments are based on the idea that a company that does not have financial and strategic achievements is not described as “disruptive”. Consequently, they put two arguments forward:

- – Disruptive innovations originate in low-end or new markets. Disruptive innovations are actually made possible in two types of markets that are neglected by traditional operators. The latter place less importance on the less demanding customers and focus on the most profitable customers. The disrupters intervene by offering products and services at low prices.

- – In the case of new markets, disrupters create a market where none previously existed. Simply put, they find a way to turn non-consumers into consumers. For example, in the early days of photocopying technology, Xerox targeted large companies and charged high prices to provide the performance required by its customers. School librarians, bowling league operators and other small customers, whose prices were out of the market, managed with carbon paper or mimeographs. Then, in the late 1970s, new competitors introduced personal copiers, offering an affordable solution for individuals and small organizations – and a new market was created. From this relatively modest beginning, manufacturers of personal photocopiers have gradually acquired a major position in the photocopier market.

According to these authors, Uber did not initiate any of the innovations. It is difficult to argue that the company found a low-end opportunity: it would mean that taxi service providers had exceeded the needs of a significant number of customers by making taxis too numerous, too easy to use and too accessible.

Uber didn’t just target non-consumers either: it also targeted those who found existing alternatives that were so costly or inconvenient that they used public transport or drove themselves. Uber was launched in San Francisco (a well-served taxi market), and its customers were generally people who were already present that used to rent vehicles.

Christensen’s criticism is methodologically based, in other words, it has taken the opposite path to the practices of disruptive innovation. Disrupters first attract low-end or unserved consumers and then migrate to the traditional market. Uber has taken the complete opposite approach: first positioning itself in the consumer market and then attracting historically neglected segments (Christensen et al. 2015).

Uber remains a disruptive company, as it has increased demand by developing a better and cheaper solution to meet its customers’ needs. Thus, many companies follow Uber’s example and are establishing themselves in the sharing economy, and even if they are not disruptive innovations, they still disrupt the stability of large companies.

3.4. Major issues of the sharing economy

The sharing economy is mainly an access economy: sharing is a form of social exchange that occurs between people who know each other, without any benefit between members of the same family.

Once it takes place in the market where a company acts as an intermediary, it is no longer sharing, because the consumers pay in order to have access to goods and services; it is an economic exchange for which consumers seek a utilitarian value rather than a social value (Eckhardt and Bardhi 2015).

In this case, since the sharing economy only has the “sharing” title, is it not increasingly likely to become a “hegemony” of the economic model?

Not necessarily. In the research carried out so far, the sharing economy seems to be a natural result of multiple social interconnections and is therefore a major trend, in addition to also having several advantages for our society. It meets the environmental, economic and social requirements of society.

Apart from rationalizing the use of natural resources and reducing the volume of waste, consumers are adopting a new consumption style. Indeed, the sharing economy frees consumers from restrictions linked to ownership, oriented towards identity-based positions. In addition, considering the ease with which goods circulate in the economy, the country would be less dependent on exports (Ertz et al. 2017).

Furthermore, technology has all the assets to overcome any obstacles it may encounter. However, it needs political and regulatory support in order to enhance and make the transition to this new economic model a reality. Admittedly, the sharing economy appears to be a social matter, but in reality, transactions are regulated by the market. Thus, consumers are driven by the goal of maximizing their satisfaction and the companies, by the realization of profits.

As a result of this last reflection, the sharing economy raises certain issues. Referring to Pascal Terrasse’s work on the development of the collaborative economy, his report identifies 19 proposals for developing the sharing economy.

This report provides information on two major issues that are intended to be adopted by public authorities (Acquier et al. 2017):

- – the collaborative economy must be subject to the same law as the traditional economy;

- – the collaborative economy must be valued, in particular for the benefits it brings to society. It provides employment opportunities and encourages innovation.

Furthermore, collaborative consumption has the power to counter decadent consumerism and provide a framework for sustainability, based on community sharing: “Sharing makes a lot of practical and economic sense for the consumer, the environment and the community” (Acquier et al. 2017).

Waste reduction is reflected in the circular economy, which aims to use products and components of the highest utility throughout their life cycle. For example, in its goal of zero waste, San Francisco City’s online platform, named Virtual Warehouse, recycles used appliances, office furniture and supplies (Ganapati and Reddick 2018).

Ganapati and Reddick believe that there are four main challenges to the foundations of the sharing economy:

- – first, rental could have serious disadvantages, creating new class divisions and more inequalities;

- – second, Internet platforms are not necessarily egalitarian. They are themselves giant companies that reduce the benefits of immigrant workers;

- – third, the long-term benefits of the sharing economy are not clear;

- – fourth, there are security and trust issues related to information sharing.

It is apparent that the sharing economy is facing a wave of challenges that discredit its effectiveness and sustainability. There is also the question about the problem of trust between users and start-ups, and between users themselves. However, the sharing economy also presents regulatory and legislative challenges.

3.5. Conclusion

Digital technology has fundamentally disrupted people’s daily lives and the behavior of economic agents: consumers and producers.

Although the consumer has easily gotten used to just clicking on a keyboard to satisfy any need, this is not the case for companies in the traditional economy.

The sharing economy, commonly referred to as the “platform economy”, involves certain risks for companies that refuse to be immersed in this new economic model. Indeed, the phenomenon of uberization does not provide any relief and it is always seeking out commercial transactions, especially given that that it has a major asset: “cost reduction”.

However, this new economic model faces certain issues and needs to be structured. It must carefully meet the expectations of individuals by protecting them and preserving the natural environment in which they live, through both regulatory and legislative measures. Lastly, to regulate the practices of the sharing economy, it must be equipped with economic policies, which in this case, is fiscal and monetary policies.

TO REMEMBER.– The sharing economy is booming and attracting attention. Its contribution lies in changing the perception of consumption, the consequences of which affect production activity. It is not without its risks for industries.

To avoid the full impact of inconvenient consequences of the sharing economy, industries must rise to the challenge, gradually adapt to its rules and take advantage of the new situation, bringing about new opportunities.

- 1 John Francis “Jack” Welch Jr., born November 19, 1935 in Peabody, Massachusetts, is an American businessman, former president of the American group General Electric from 1981 to 2001 and one of the most emblematic leaders in the United States during the period of 1980–2000 (source: Wikipedia).