Think back over the oddest moment of your day, or the strangest encounter, or the most puzzling problem. What story would you tell your five-year-old when you get home?

How ?

This book offers many examples of ways we can show our work. Whatever appeals to you and whatever approaches you wish to take, it’s critical that someone—and it might as well be you—be the leader. This book is aimed at readers from all areas of an organization, from frontline workers to CEOs, and at those who don’t work within an organization at all. Whatever your place, the key to getting started is to . . . start. Be the first one to go, the one to set the example, the one to lead the effort. This chapter offers tips for managers, trainers, workers, and people just helping each other. Maybe everyone won’t follow suit. But a few will. And it will grow from there.

SHIP IT

- In looking for ways to get started, pay attention to things already in place that can be leveraged: internal tools, social tools being used by the marketing and information offices, that kind of thing.

- Locate ambassadors. These are not “champions,” rah-rahing about how everyone needs to do this. They are the ones already doing it: they tweet about their work, they upload presentations to SlideShare, they include images in their weekly reports. They are already using tools and demonstrating a willingness to share. Look to them for help and ideas.

- Break old habits and force use of new tools and approaches. For instance, Alcoa’s Joe Crumpler and Brian Tullis advise: If you distribute an artifact (file, page, presentation, etc.)—link to it. Do not send the information itself unless it’s absolutely necessary. No more email attachments, in other words.

- Encourage one another. Offer “likes” on items or comments when a tool makes that available. Ask questions. Extend conversations where that makes sense.

- Organize around roles, not around the O-chart. Set up spaces and tools so everyone in sales across the organization can communicate with all their colleagues. Or customer service providers. Or trainers. Or people who work with budget processes.

- If you have them in place, work with community managers to connect talent pools, interests, and resources, and to identify areas ripe for showing work.

- Make more things public.

- Instead of asking for just “results” on reports, ask for one line on obstacles encountered and how they were overcome or a description of an unexpected delay and how it was resolved; or mention the person who turned out to be key contact.

- Teach people to create useful profiles, not just job title-degree held. What are their passions? What do they feel they excel at? What is some little-known ability? You never know when you might need someone who speaks Tagalog or knows how to tune a piano.

- Link things—reports, publications, presentations, worksheets—to real people with those useful profiles.

- Workers have to feel that it’s worth their while to do this. Learning something from others, getting a solution to a problem, finding expertise when they need it, will encourage them to participate more than will an order to post something every Friday.

- Look for where natural communities exist. All organizations have “unsanctioned” or informal communities, from people who engage in a certain task to those with particular backgrounds or degrees, to others with common work roles.

- Ask, “How did you do that?” and “How did you learn to do that?:” and “Can you show me how to do that?” and “If you did that again next week, what would you do differently?” Learning how Pearl Fryar creates gorgeous, living topiaries does not come from saying, “Please write down what you did this week.” Try asking: “What are you working on?” “What problems did you run into?” “What went easily? What turned out to be more difficult than you thought?” “Where did you have to stop to look for something, or someone?”

- Figure out ways to get it in front of people: Yammer’s Allison Michels often asks, midway through a long afternoon, “What are you doing right this second?” and gets fascinating tidbits about processes, projects, and daily challenges and obstacles. Have an autoreminder set up so you’ll remember to do it.

- Replace existing activities:

- Instead of meetings, we will ____________________________

- Instead of status updates, we will ________________________

- When you finish a presentation, _________________________

- When you complete a sale, _____________________________

- When you ______ (take a break, finish a task, come back from lunch...)

- Once a _______, write down or post a comment or share a photo.

- Start thinking about new roles—some we’re still inventing—and who might fill them. The future will include people with roles like Community Managers, Curators, InfoWizards, Data Wranglers, and Connectors.

- Organize around roles instead of silos. Look for existing communities, even unsanctioned ones (every organization is filled with bootleg communities). Work with community managers or those who appear to be influential within communities. Look for natural communities and easy wins: new hires. Alumni of the corporate leadership academy or sales training. Focus on smaller groups. And as you’re starting, focus on those who are willing, who will serve as ambassadors for the effort.

- Encourage serendipity. The United States’ National Public Radio (US) National has held “Serendipity Days” in which about fifty employees from different departments volunteer to get together to brainstorm about projects. Partly this is to encourage people to “work with groups you wouldn’t ordinarily work with through the course of your week,” according to NPR’s senior director of talent acquisition and innovation. (Source: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323798104578455081218505870.html)

- Ask, “How did you do that?” and “How did you learn to do that?” and “Can you show me how to do that?” and “If you did that again next week, what would you do differently?” Then talk about where and how to make that visible/discoverable.

- Look for easy wins: New hires will do as they’re asked without saying, “That’s not how we’ve always done it.” Set up a site, like a Facebook group or internal wiki, where graduates of the company Leadership Academy can, as part of follow-up coursework, post to their community discussing their successes and areas in which they still struggle.

- Link. Blog contributions should link back to the contributor’s profile. Reports of work done by a project team should offer links back to all the team members’ profiles. Discussions of using an internal tool should include a link to the tool. Conversations about an item in a policy should include a link to that section. Stop enabling less useful activities, like attachments to email.

- Focus on smaller groups, and focus on reality. Not everyone will be a willing sharer. Not everyone will contribute equally. Focus on those who get on board more quickly and work from there.

THIS SHOULD NOT BE HARD. Whatever you decide to do, it shouldn’t require custom platforms, two days of training, and a task force working up an implementation plan.

NAME THINGS

One of the biggest challenges in information management is what to call things. This is compounded by users who do things like rename documents rather than just giving them a new version name. If there is one thing that needs to be formalized it’s probably issues around names, tagging, keywords, and folksonomies. Teach that.

As Brian Tullis and Joe Crumpler note in their “Next Things Next” blog: “No matter what Google says, it is important to give search engines some help. You need to be ‘discoverable,’ and a great route to that is through naming conventions. There is an art to naming files, articles, web pages. Think about your audience and have some discipline to how you ‘name’ things within your organization without going overboard into taxonomy hell.” http://nextthingsnext.blogspot.com/2010/11/tug-2010-observable-workshop-notes.html

PLATFORMS, TEMPLATES, FORMATS

Joe Crumpler, senior manager at a large aluminum manufacturing company:

Jeroen Sangers uses an ongoing daily-journal process, shown in the next column.

As much as possible, let people use the tools they like best, and let them use public tools if they like. One of the problems with enterprise social networks, as Harold Jarche has pointed out, is “Even with a clear resonating purpose, salaried employees still own nothing on the enterprise social network. Aye, there’s the rub.” (http://www.jarche.com/2013/05/social-networks-require-ownership/.) Or if they are already sharing work, recognize that, within the rules or organizational communication policies, they may want to replicate it. Some employees post to the live feed in the company learning management system (LMS) but may choose to repeat the posts on Twitter or on their Facebook pages—or vice versa.

HOW NOT TO DO IT? DON’T OVERFORMALIZE OR OVERENGINEER

As Charles Jennings says, the point of showing work is to extract the learning from it, not impose more work on it. The busy knowledge worker or copier repair technician has little time or patience with one more complex, formalized process. Try to think of showing your work as an act of generosity, of helping each other out, not as another onerous task to perform.

NOT THIS, IN OTHER WORDS:

Think about what is quick and easy and makes sense in the context of work. For the copier tech it may be taking a smart phone photo of a broken part and posting it to a community wiki. For the knowledge worker it may be uploading a finished presentation to a shared site along with a microblog message: “I just uploaded the specs for the Jacobs project . . . .”

Do have some basic ground rules. A couple solid ones? “No anonymous posts or comments” and “when it’s evident a conversation needs to be kept between two people, move it to a private channel.” Consider what needs to be shared where: some things may only need to be visible to the immediate work team, while others can be placed on a public site. But beware “resistance by delay” behavior, where endless meetings about processes and protocols about showing your work—in the name of making it all perfect—prevent any actual activity. Utilize communication policies already in place, and use the image at right to frame conversations about which items best go in which area.

CONSIDER THE VALUE OF MAKING THINGS PUBLIC

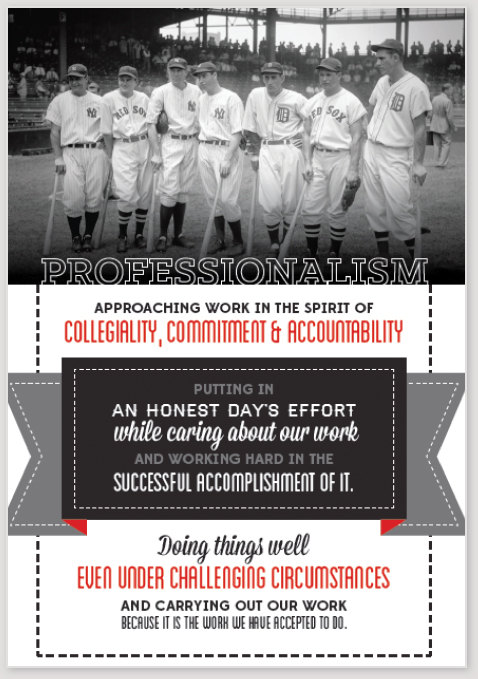

While it is natural to worry about letting workers just talk about anything on public forums, this isn’t a new problem. After all, the introduction of the telephone presented similar challenges. We have rules about public disclosure and organizational communication policies to guide what can be said where. But avoid the temptation to think of everything as “confidential.” You may recall seeing in the “Workers: What’s In It For Me” section the example of using Google Docs and Twitter to crowdsource a definition of “professionalism” as part of an organization’s code of conduct.

The result:

I used this poster as an example of showing my own work in a “Show Your Work” workshop; a participant from Australia used it to create a poster for his workplace kitchen.

Courtesy of Lee Woodward

Showing work can help to amplify and grow a message, and help tools and ideas find reuse. Consider the nature of conversations: Is there any reason to keep a discussion of the organization’s code of conduct secret? It’s something that, even if not open to the whole world, would probably serve to generate some conversation between organizations and their customers and suppliers.

And consider: Organizations sometimes seem unaware of who makes up a worker’s real network. There’s a tendency to view workers in a building, or on a floor, or in a suite interacting with those in the immediate area. But a copier repair technician’s network involves other technicians, and the customer who owns the machine, and maybe engineers, and possibly even vendors of auxiliary products like paper or toner. There are legitimate business reasons for some conversations to happen outside the work unit and the organization.

“Social communities leverage an increasingly expensive asset—people—by allowing them to work out loud, connect with more people, establish trust, and find relevant information and solutions more quickly,” proclaimed Rachel Happe of The Community Roundtable . . . . [who] suggested that human capital investments may still be at odds with technology investments, which are supposed to reduce the burden on knowledge workers.”

http://scn.sap.com/community/business-trends/blog/2012/10/09/work-out-loud-screams-sap-radio

TOOLS AND STRATEGIES

Finding the right motivation and medium are critical. Whatever tools are used—from Post-it Notes to complex custom platforms—success depends on making them easy to get to, easy to search, and easy to use. While it may not always be possible, try as much as possible to work with tools people already like using. Some of us are PowerPoint whiz-kids, while others love to shoot quick videos. Some of us are writers—and some of us aren’t.

Popular workplace tools for showing work are publishing tools like blogs, collaboration tools like wikis, chat/microblogging and instant messaging products, slide- or presentation-based tools. Sometimes these are used in suites, like SharePoint (internal) or Google Drive (public). There are robust public tools like Facebook and private groups within Facebook. There are robust private tools like Basecamp and Jive.

Choose tools that make sense. If technicians need to offer photos or videos of repairs, where will they go? Will they/how will they be stored? Will they/how will they be tagged or linked? Photos can easily be shared in at least a dozen ways, including sending via text, submitting to a shared private album, uploading to a Facebook group, sharing internally via Yammer, publishing to the world via Twitter, or pinning to a Pinterest board. And most importantly: What are they (or you) already using?

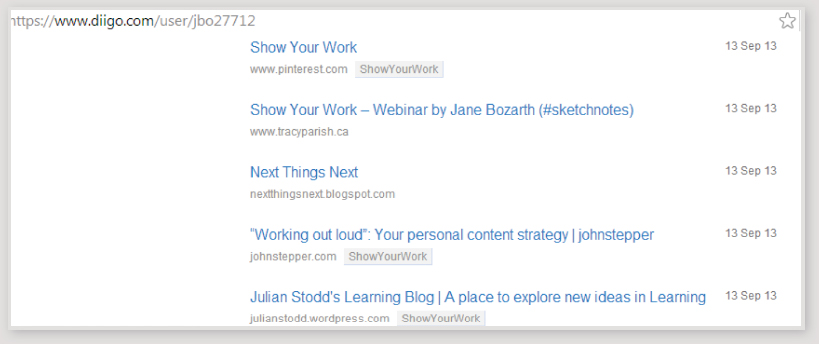

An easy starting place? Shared bookmarks. Tools like Diigo and Delicious will let individuals share their own bookmarks relative to a particular topic or interest area; group capabilities allow everyone to share what they’re reading, what they found useful, what they are using as resources for presentations or reports. Viewers visit a single URL to get access to all the bookmarked items; those doing the bookmarking can add comments to the things they’ve chosen to share. A list of items associated with showing workis shown here.

Evernote offers a broader view of this idea, allowing viewers to clip, store, and share beyond just bookmarks to whole articles, single images, and the like.

Showing your work via presentations is especially easy for those who are creating presentations anyway. Slide shows developed for public presentations, reports, sales pitches, or training can be shared. The most popular presentation-sharing tool at the moment is SlideShare, which allows quick upload of slides along with options to add audio, allow for comments, and follow those who show their work there.

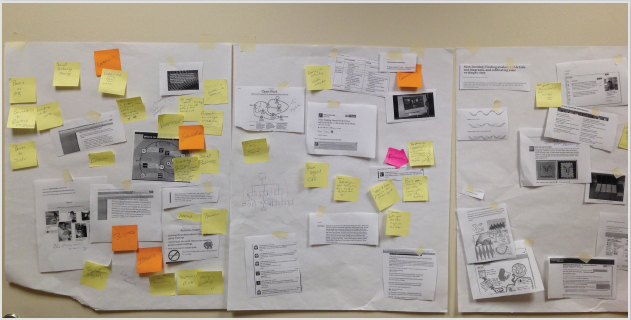

There are many canvas tools available. For small ones—that can be viewed on a computer screen—products like mural.ly allow for individual or collaborative development of online murals that can include easily moved and resized images and text. Users can create and share projects, start discussions around any section of a mural, @Mention others to bring them in or speak directly to them. Changes are tracked. Here’s an example of a Mural.ly showing the creative process.

VIDEO

Video can be captured now with even inexpensive mobile phones and shared via channels like YouTube, Vimeo, or TeacherTube, which offer varying levels of privacy settings and subscription capability. Items can also be linked to other tools. Video files can be shared directly to sites like Facebook, or sent via text or email (beware here of file sizes and data charges). Depending on the product the videos can be easily enhanced. YouTube, for instance, provides annotation tools and some ability to edit after the fact.

Doctors are now experimenting with wearing Google Glass during surgery, which allows students to quite literally see through the surgeon’s eyes. You can capture and save video with Glass, or connect the live recording to a Google Hangout so viewers can join in real time. There are enormous possibilities for showing an eye-view of activities such as repairs, construction, processes, corrections, and interactions. Glass can also capture still photos.

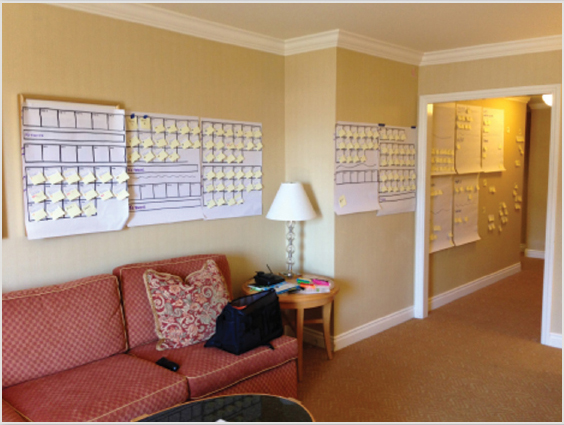

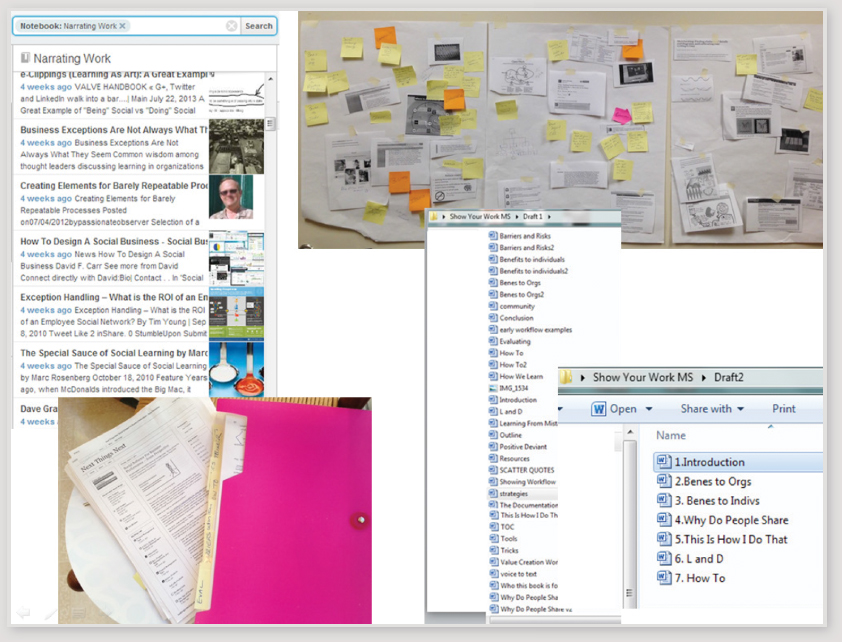

Planning this book

Tools like “sticky notes” can be used for planning a project or event. Color notes can further mark out specific elements or people responsible.

(Note: there are online “sticky-note” tools, too.)

Mobile devices with cameras are at near-ubiquitous levels, and Pew Internet Research reports that half of all adults online are now sharing and uploading their own images. Photos are an excellent way of showing work and are easy to share across many platforms and tools.

Tracy Parish similarly created a sketchnote of a “Show Your Work” session, took a picture of it, and put it on her blog—then tweeted to her followers that she had a new blog post.

By 2014 the marketplace anticipates that the new iSketchnote will ship. It’s an iPad cover that will send the drawn image directly to the device, without having to take a photo.

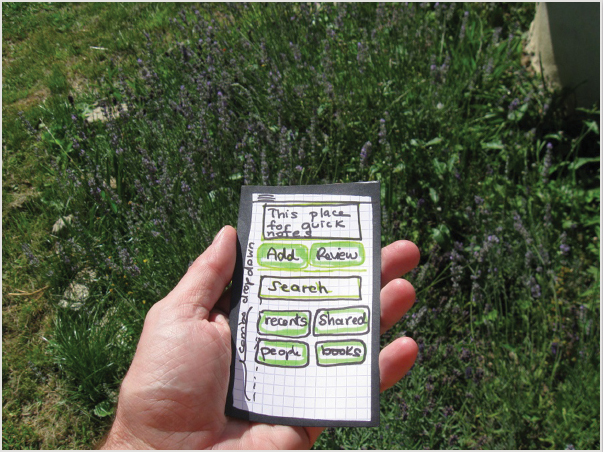

Kevin Thorn sketches out a new project, then shares a photo on public social channels in the next column.

As discussed elsewhere, low literacy workers, those not comfortable with writing, and those who are just busy may find the need to stop and write down what they’re doing too time-consuming or onerous. There are a number of voice-to-text tools that can help, and will send voice posts to blogs, wikis, even to Facebook and Twitter. These emerge and evolve all the time so look around to see what’s currently available. At the moment they are most reliable with relatively unaccented American voices but are getting better. Take a look at Dragon Dictation, ShoutOut, WordPress’s blogging tool’s post by voice feature, and iPhone’s Siri.

In considering “Which tool is best?” it matters more to ask “What’s comfortable and easy to use and fits easily within workflow?”

REMEMBER TO TURN THE RECORDER ON

Half the trick to showing your work is ... remembering to do it. One morning in 2012 tech-guru Gina Schreck wanted to test Skype’s still-in-beta ten-way video calling feature. She posted a Tweet asking for help (you can’t test ten-way video by yourself, see?) and within a few minutes several other people hopped on the call, the author among them. We learned a lot of things—primarily, that there’s a reason things are in beta—but the experience isn’t limited to just the few of us. This is of value to people who have a bit more trepidation with tech than Gina, or who don’t have a community of people who will jump onto an impromptu call, or who need to show an example of “why we need Skype” to some administrator or IT person at work. Luckily, as we were starting, Gina thought to turn on on her screen recorder. She later made the recording of the experiment available on YouTube. At last check the video had been seen by nearly a thousand viewers.

DRAW A PICTURE

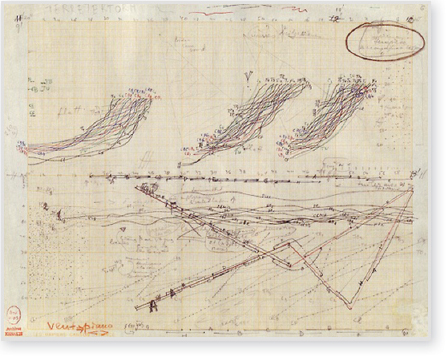

Music has a long oral tradition and is usually a very social experience, with songs handed down and techniques swapped from teacher to student and among musician communities. Check YouTube sometime the number of videos offering help in playing a particular piece on the guitar. Those who’ve learned (or tied to learn) to read music know that traditional music notation has limitations: you can see how a piece should sound but not necessarily how it should feel. Try listening to ten different recordings of any piece of music and you’ll likely hear a good deal of difference, even though the same notes are being played all ten times.

Some composers, sharing the frustration with traditional notation, have chosen to use a graphic approach to music. This drawing by Xenakis, for instance, attempts to show the “shape” of the piece.

“Study for Terretektorh” (c. 1965-1966), © Fonds Iannis Xenakis, Bibliothéque Nationale de France

In explaining his idea for a new user interface, Bruno Winck drew it, then showed how it would look in context (and then took a picture of it).

A case study about encouraging narrating work using Yammer. Within Microsoft. Which owns . . . Yammer.

A 2013 Citeworld.com post offered highlights of an interview with Chris Slemp of Microsoft’s IT department. “Our plan for driving adoption includes a mix of broad value proposition messaging such as ‘Amplify your influence,’ working with teams to replace their distribution lists, and lining up line of business applications for integration with the social platform,” he said. “We believe that it’s this integration that will drive the biggest culture shift. Employees will just naturally be using social feeds as a part of their jobs in the CRM or engineering tools they use every day.”

“Another key to success was not exercising too much control. The power of Yammer is in its ability to enable employees to very quickly self-organize across geographic or organizational boundaries, and around any project or initiative. To realize this benefit, governance is kept to a bare minimum.”

Slemp added that Microsoft hasn’t been very concerned about quantifying efforts and outcome, but is focused on looking at adoption and the emergence of influencers, and developing use cases to demonstrate value to others in the company.

http://www.citeworld.com/social/21968/microsoft-employees-using-yammer

WORKER CONCERNS

A number of spots in this book offer pointers on dealing with privacy and security concerns, many focused around using existing communication policies and asking, before locking things inside a silo, “Is this really proprietary? Must it be private?”

Employees may have some internal fears about showing their work:

- Not knowing how or what to show Solution: Watch for examples, like the ones in this book. In reflecting on or in conversations about obstacles and successes and roadblocks and workarounds, ask, “How can we make that more visible? Who else could learn from that?” Create (or join) some role-based communities (HR specialist, sales rep, accountant, nurse, teller, developer, etc.) and listen to what people talk about. They are sharing their work all the time, even though they may not call it that. What do they need? How can you help? What are you doing that would be of use to them? What would you like for them to narrate?

- Needing some help with the tools Solutions: 1. Choose good tools. Things should be easy to use, and be accessible without jumping through hoops like additional logins. They should fit well within the workflow. 2. This is a good opportunity for the training department (L&D) to help people with learning about new tools. But back to point 1: the tools shouldn’t have a long learning curve.

- Fearing what they show won’t be useful Solution: Encourage commenting and feedback. Ask others to add to the project or conversation. Encourage reuse and be sure to link back to the originator so he or she will see that what he or she is showing is in fact useful.

- Lack of time Solution: Showing work should replace some things currently taking up time, not just eat up more: replace meetings and activity reports. Take real assessment of how much time in a day is spent on email. Replace it. Ask people to keep a calendar for a week, noting how much time was spent looking for something or someone. Replace that with making work more discoverable.

- Fear of not getting credit Concern: This one is harder as it is tied to organizational culture, which can be wickedly difficult to change. People who work in an environment in which sharing is punished aren’t likely to do more of it. People who are in competition with one another for bonuses or workplace awards or other gears in the incentive machine might naturally hoard what they know. If they’re afraid they won’t get “credit,” then why would they show their work? As blogger John Stepper says: People competing for a slice of a finite pie won’t share. Psychology 101 teaches us that all behavior is purposeful. People will do what they are rewarded for, and they will avoid punishment.

- Fear of being criticized or being made fun of Advice: Yammer’s Paul Agustin reports this as his own internal hurdle when he first began showing his work, especially when things were in an in-progress rather than finished-polished state. But working in an atmosphere where people must use their real names to engage, and are expected to behave civilly, taught him to trust his peers.

- Fear of talking Advice: Years ago a colleague came back from a “meeting management” class intent on implementing something called a “Zinger Jar.” The idea was that during meetings a glad jar would be placed at the center of the table. Any time someone was sarcastic, or disagreed inappropriately, the group would call “Zinger” and fine the speaker a quarter. In a matter of days nearly every word anyone said was labeled a “Zinger.”

- Fear of exposing failure Solution: Work on developing a culture in which failure is tolerated. Consider the alternative: failures that have been hidden can often create bigger headaches later. Recognize that one overreaction to failure can undermine trust and confidence for a long while. Limit conversations where they need to be. Not everyone needs to be privy to every piece of information. Who needs to know about the mistake? Provide spaces where workers feel comfortable, for instance, in writing to the ten people who should know about the mistake, not the entire workforce and all the customers. Consider: What is the cost of not showing a failure? Teacher Sarah Wessling could have generated a 6-minute video of her perfect lesson plan and her perfect students and their perfect learning from it. Instead she offered 27 minutes showing the lesson crashing and burning, then showing how she fixed it for the next class. This is infinitely more valuable to practitioners and is possible because Wessling has the confidence to show her failings while working in a culture in which one lesson salvaged is not treated like the end of the world.

Some companies have even begun rewarding failure, “Better Ideas Through Failure,” Wall Street Journal, September 27, 2011, particularly if learning is tied to it. For instance, SurePayroll systems offers an annual cash prize, but only those who try to do a good job, make a mistake, and learn from it are eligible to win. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204010604576594671572584158.html

Managers: Where/Who is the real obstacle? Employees routinely report that the “Network Administrator” is the one blocking their access to tools. Really? Is your organization letting the network administrator set policy? And consider this, from a “Show Your Work” webinar participant: “If the base media person would cooperate we could record the community of practice meetings.” A follow-up conversation revealed that the media person not only refused to help the group but refused to loan equipment and then, when workers offered to use their own equipment, invoked a rule saying workers could not video themselves even for in-house use. Are you aware that your organization’s community of practice members want to better document its activities, but your media person is stopping them?

EVALUATING EFFORTS

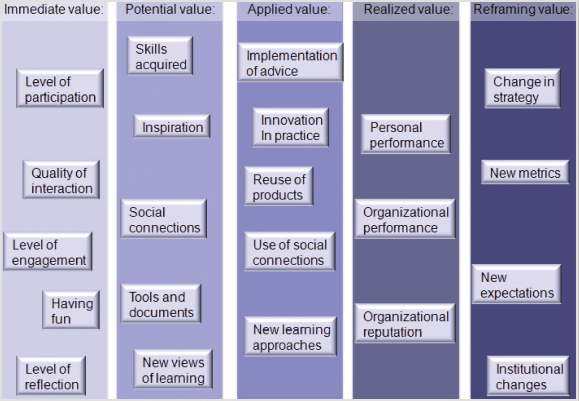

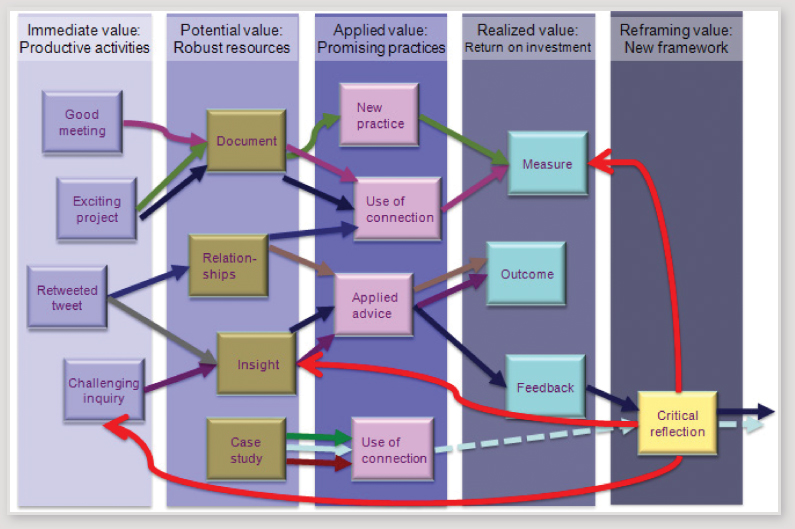

Microsoft’s Chris Slemp says that early efforts at enterprise-wide adoption of Yammer focused more on uptake and emergence of influencers. They recognize that there is no magical algorithm that will help calculate ratio of items shared to outcomes. Those wanting some additional ideas for assessing the value of showing work might be interested in a new conceptual framework developed by Etienne Wenger, Beverly Wenger-Trayner, and Martin deLaat. It looks for ways to identify value across a range of outcomes, from immediate to potential to applied value: why people participate/share in the first place, whether they are making useful connections with others, whether new tools and artifacts are being created and seeing reuse, whether advice is implemented. Moving across the framework to the final two columns, the framework asks for data regarding the effect on personal and organizational performance and, ultimately, whether the organization has begun to work differently.

Applying the framework to efforts—which will depend a great deal on workers knowing how to report on what they’ve shared, with whom, and the results of that, will ultimately show activities looping back on each other as talent and expertise connects in meaningful ways.

WENGER VALUE-CREATION STORY WORKSHEET

When showing work that involves participation in a network or some collaborative effort, Wenger encourages helping workers be mindful of the value in the experience. Consider submitting this (or asking workers to submit it) instead of requiring whatever activity report is currently in place. Among the tools offered by Wenger et al. is the worksheet on the next page for tracking information across the framework.

For more on the framework, including details on gathering data, see Wenger, Wenger-Trayner, & deLaat, http://wenger-trayner.com/resources/publications/evaluation-framework/

| NAME | THE EVENT, INCIDENT, PROBLEM, ACTIVITY, DECISION, ETC. |

|---|---|

| Typical Cycles | Your Story |

| Activity Describe a meaningful activity you participated in and your experience of it (a conversation, project, working session, online interaction, etc.) |

|

| Output Describe a specific resource this activity produced for you (an idea, document, other) and why you thought it might be useful |

|

| Application How did you use this resource in your practice? What did it enable that would not have happened otherwise? |

|

| Outcome a. Personal: How did it affect your success or reputation? b. Organizational: Has this contributed to the success of this organization? How? |

|

| New definitions of success Did this change how you think of “success”? How? |

LEADERS NEED TO SHOW THEIR WORK, TOO

If you are the organizational leader, look to the example set by Richard Edelman. And take a look at Paul Levy’s “Running a Hospital” blog at http://runningahospital.blogspot.com/. Publish annual plans, and include tangible items people are working on. Even better: publish your thinking. Talk about an especially difficult decision or task. Talk about three things that are going well. Talk about what you had hoped to do when you first stepped into the role, and what reality has taught you.

If you are someone with some control over how visible the activities are within your company or your team, I have some suggestions for you to try immediately:

- Post your own personal performance objectives in a public place in your organization. If your employees know what your objectives are, they might get a clue on why you are asking them to do certain things. If they know what you are being held accountable for, they can help make you successful.

- If you have a strategy or some sort of annual plan, post it in a public place. That plan should make explicit references to real, tangible efforts being worked on by your team.

- When you ask your employees to do something for you, or start a project that involves them, take the time to tell them why. Give them context, discuss linked initiatives, relative priorities, and show them how they are fitting into the big picture.

- The next time you create an electronic document at work (or intranet page...), link it to at least one other document or page, to enrich the context of the new piece of information.

- The next time you set up a workspace / collaboration site / intranet portal area or even just a file share, give the entire company access to read it. If you can’t justify giving the entire company read access, just try for 2x the original number of intended readers—and then let them know that they have access to it.

- Explicitly encourage and reward collaborative, visible work.

Crumpler, http://nextthingsnext.blogspot.com/2011/04/whats-vis.html

CASE: THE SOCIAL COO

Post from http://nsynergyblog.com/2013/08/26/leveraging-social-tools-to-drive-culture-and-adios-15000-emails/ By Peter Nguyen-Brown, nSynergy COO and Co-founder

BE HONEST: ARE YOU READY? WHAT DO YOU NEED TO DO?

A successful organization-wide effort at showing work will depend in large part on the organizational culture. Open Leadership’s Charlene Li offers this questionnaire to help you assess readiness and identify areas in need of some tending.

This material is reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

WHAT WORKS? LESSONS LEARNED

As mentioned earlier, Hans deZwart conducted an early experiment in narrating work using a microblogging tool with his virtual team (eighteen people total) at Shell. Findings? No one likes the idea of mandatory numbers of posts or comments or deadlines. The posts most people preferred were shorter and timely—as close as possible to the actual performance or event. Participants also preferred posts that were more than just a summation of results, but the thinking that led to them or issues encountered along the way. Apart from being interesting, these were the posts that tended to draw additional conversation and help. One more thing? Posts that revealed something of the author’s personality, especially wittiness or fun, and “sharing excitement or disappointment humanizes us, and that can be important in virtual teams, especially in large corporations.” http://blog.hansdezwart.info/2011/07/19/reflecting-on-the-narrating-your-work-experiment/

SOME REALITIES

The “legacy information” problem that besets us elsewhere is still present here. Teams change, people come and go, projects are shelved and revisited, people keep renaming the same document. As with websites, it’s important for someone to occasionally revisit places and documents, archive old data, and ensure obsolete processes and finished projects are labeled as such. Eventually, this should level out, and the more the work that is visible the closer to accurate everyone’s telling will become.

There is also the problem of self-reported data. People exaggerate their accomplishments; they hide mistakes, they take credit. We all need to be heros and often in the retelling our stories put us in that role. But remember, it works both ways: people who are afraid to admit that a project isn’t finished, who have been punished for admitting mistakes or failing to manage obstacles, will naturally try to avoid having that happen again.

WHEN?

A question for those just getting started is on the matter of when to show your work. This book offered examples of everything . As with many things, the answer here is, “It depends.” While the idea of “narrating” suggests talking as you go, there are some cases when showing a finished product or completed project, or offering a writeup of critical incidents rather than daily diaries, makes sense. Be careful, though, of holding on to something until it’s perfect, as more energy ends up going into polishing than into the real bones of the issue. Encourage people to share—and accept without criticism—drafts, sketches rather than polished images, and roughly final ideas.

While it’s natural to want to share the perfect, polished, finished product, showing works-in-progress, or at least before-and-after work, can help others understand what is involved in a task. Most things we do do not emerge full blown in one try, but those who don’t do what we do often don’t fully realize that. Here’s an example from designer Kevin Thorn’s work in creating characters for an HIV awareness campaign.

Likewise, a nonfiction book is often about organizing what it likely to be an enormous amount of source material and personal notes down to a final collection (lower right).

In this example, showing work in progress helps to educate the audience about the process. It is also a natural vehicle for showing stakeholders the real status of a project or asking for help when one is in need of getting unstuck.

JUST DO IT

OpenText’s Kimberly Edwards on the dangers of knowledge hoarding and a reminder that the way to get started is to . . . start:

THE END

So the concluding questions: How can we be better about narrating our work? What did we do today that was worth capturing, that might help someone else, that might make something more discoverable in two years?

How can we encourage others to narrate their work? What support or tools would enable that? How about the repair technician who figures out a new, quicker workaround? Or the restaurant chef who develops a new technique? Or the software engineer who . . . ? Or the paralegal who . . . ? What opportunities are we missing? What can we do to help connect the dots across the silos of an organization, or profession, or area of interest?

ASK THE RIGHT QUESTIONS

Learning how Pearl Fryar creates gorgeous, living topiaries does not come from saying, “Here’s a pen. Please write down what you did this week.” We need to stop asking, “Can you tell me what you do?” People have a hard time answering that, and usually just end up listing activities. Instead ask, “What are you working on?” “What problems did you run into?” “What went easily? What turned out to be more difficult than you thought?” “Where did you have to stop to look for something, or someone?” In other words, ask: “How did you do that?” “Can you please show me how to do that?” In other words: we could learn a lot if we did less telling everyone how to do their work and asking them to show us what they do. People talk about their work all the time. Supporting them as they show their work is a great way to help them keep talking.

People talk about their work all the time. How can we make that more visible?