Knowing what gets done is not the same as knowing how it gets done.

Benefits to Organizations

Narrating work offers myriad benefits to organizations, from better locating talent and finding tacit knowledge to increasing efficiencies to improving communication. One of the problems with traditional knowledge management is the temptation to try and oversimplify an unavoidably complex task. Building a house takes much more than a blueprint; a schematic of a manufacturing process may, from 50,000 feet, look like a series of simple steps but on the shop floor be a very different proposition with many moving parts and frequent exceptions.

“If everyone in the team narrated their work openly, we wouldn’t need any meetings to assess project status and we would gain a lot of time.”

∼JEROEN SANGERS, http://en.blog.zyncro.com/2013/05/16/working-out-loud/

But they don’t tell us the story the person in charge of the process, on the floor, every day, would tell: what to do when a supplier fails to ship a critical component, or a flu epidemic derails schedules, or someone creates a custom shim for an ill-fitting part without telling anyone about the flaw. The problem with documentation? Well . . . the reality is rarely what’s documented. So how can showing work help the organization?

INCREASED EFFICIENCIES

- Reduction in meetings

- Fewer silos and decrease in redundancy

- Saved time and energy

- Reduction of time spent both in searching for information and people/relationships

- Reduction in time spent interpreting historical documents and artifacts

- Connecting talent pools

- Improvement in creating and storing information and artifacts

- Capturing explicit, but not tacit, knowledge

(Author note: This does not address the problem of meetings held from dysfunction, like creating intentional delays, discomfort with using newer, more efficient tools, simply liking to “get together” even when it is not productive, and having meetings to give the appearance of working. In other words: sometimes managers don’t want to reduce meetings. Interestingly, I have worked in two organizations fueled by “standing meetings,” in which allotted time gets filled whether there is anything important to discuss or not. I worked in a third in which there were no standing meetings, and it seemed to get by just fine without them.)

OVERCOMING TRADITIONAL ORGANIZATIONAL COMMUNICATION TRAPS

Many organizations are good at capturing basics of explicit information: to order product Z fill out form N; submit requests by Thursday. But much of our time is spent dealing with Barely Repeatable Processes, the ones that deal with people, and which often are managed through a morass of emails, lunches out, Post-it Notes, and meetings. It is, in other words, how most of us spend most of our days. They are fluid (non-rigid) processes and events with many moving parts that are not easily mapped, as with a manufacturing process.

The truth is, asking someone to “write down everything they know” or “list everything they do” just doesn’t work very well. We can find out what they do but not how they get things done. And overengineered, bureaucratized reports and documentation processes are often exercises in futility, as they capture the “what” of work but not the “how.”

The image on this page shows an example of a newly implemented process for submitting status reports. It was provided from an HR outsourcing firm middle manager who asked to remain anonymous. The IT department developed it as a way to force employees to use SharePoint instead of the less formal tools workers had been using. When I asked for detail, as the image is not very legible, the person who submitted it said: “You don’t want to be able to read it. You’ll go blind.”

A colleague working with a software group—who also asked to remain anonymous—reports: “When I was working with [A Software Company], the CEO wanted my help formulating this highly replicable process of creating video: gathering info, production planning, shooting, and then editing and post-prod into a simple linear process with a few decision points along the way. Of course, that all worked in theory, but the practical reality was that we were working with all contracted filmmakers, we had international travel issues, timezones, logistical concerns with film storage—you name it. All the things that go along with film-making. She was endlessly frustrated that the artistry of film-making would get lost in the quest to scale and flex her process, and yet she also didn’t want to compromise client service/satisfaction in a quest to streamline the people/processes that we ∗could∗ control. And there you have it.”

LEARNING FROM MISTAKES

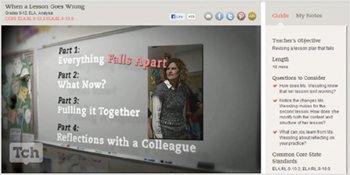

We learn so much the hard way, but are rewarded for our successes and often punished for even minor or inconsequential failures; what is learned this way is often swept under the rug. But there can be so much to learn from exploring someone else’s mistakes, especially if we can get insight into what caused them and how they were corrected. U.S. National Teacher of the Year Sarah Brown Wessling offers her own example of a devoted practitioner working to improve both her own practice and that of others, sometimes stumbling along the way. This is available as a long, in-depth video; please watch it when you have a chance. See https://www.teachingchannel.org/videos/when-lesson-plans-fail.

While her class on The Crucible was being taped, Wessling realized her lesson plan was going terribly awry. It happened that she was being videotaped that day; she went back and narrated the video, describing what went wrong and how she fixed it. Then she uploaded it to the Teaching Channel site so others could learn from it.

In class that day Wessling handed out what she felt was a straightforward assignment. But the teenage students were confused and grew increasingly loud and disgruntled. Wessling notes it would be easy to write that off to problems with listening or disrespect, but instead says, “I choose to see it this way: I’ve done something to make them act like this, because they usually don’t. I realized I had completely misfired. I didn’t create enough scaffolds for them to be successful . . . [in the end] I didn’t teach them anything.”

Wessling had 5 minutes to adjust her plan before the next class started. “What I learned from the first class is that this was too hard,” which prompted her to revisit her goals for the lesson and the big ideas she was trying to convey. She then describes what went through her mind as she reshaped the lesson even as students in the upcoming class were settling into their seats. This proves a fascinating narration of the tacit, hard-to-capture process known as “thinking on your feet.”

She then discusses the experience with fellow teacher Kate, because “these things are hard to process on your own.” Wessling comments that developing a trusted network, with people who can help you think things through and give honest feedback, is vital to successful practice. But Wessling did more. Rather than just bury the conversation with her colleague as part of her day, Wessling captured it, too, and included it in the video she shared.

Wessling did not set out to “work out loud” that day. But by narrating what happened she was able to tie the events to a larger conversation about the struggle to meet the needs of adults working with Common Core education standards, and the kids who needed to learn. She ends her commentary with a reflection on the bigger picture of what she learned from the experience, the need to adhere to standards in a way that “makes sense to the kids in front of us.”

Graphic and information courtesy of Teaching Channel, www.teachingchannel.org.

Note, too, the prompts shown on the Teaching Channel’s interface, with questions to encourage the viewer’s reflection and application to practice.

The question: Which would be more useful to the novice: An out-of-context 6-minute video of Sarah’s perfect final lesson, or the longer version showing how it evolved and why she made her final design choices?

In considering the value Wessling’s very public reflection can bring, think about the support it has: a confident practitioner, secure enough to admit she makes mistakes; an ability to recognize when something is going wrong and working to identify the root cause rather than lay easy blame (in this case, on the kids); and an administrative structure and work culture that tolerates those mistakes and sees them as opportunities to improve. Wessling’s mistake was unfortunate, but it was not the end of the world. What do more workplaces need to do to allow public reflection on ways to get better? What cultural elements currently in place support or inhibit free conversation?

Many of us have ideas that don’t match reality. Here’s a project postmortem from an anonymous gamer. It turns out an idea for a game is not the same as the reality of developing that game, and the programmer’s point of view is very different from the designer’s. This bit of after-the-fact reflection offers valuable from-the-trenches insight into something that might save someone else from learning the hard way. In this case, the gamer isn’t even known—so there is neither censure nor credit for him—but is willing to share his learning publicly.

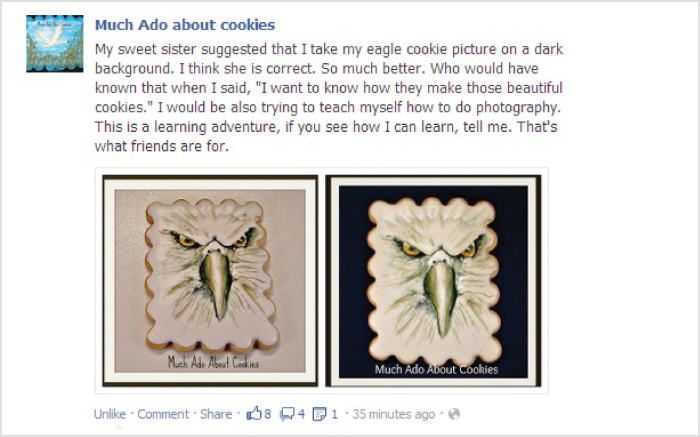

Finally, cookie baker Gloria Mercer, whom you’ve seen elsewhere in this book, shared a bit of how she made a mistake and how she learned to improve based on feedback she received. Some spinoff learning during her cookie-training phase was the need to develop photography skills. The next column shows what she posted on her Facebook business page.

Showing mistakes offers enormous insight into how work gets accomplished, and how to improve on it. Culture matters here: Do you want mistakes hidden away, likely to be repeated later, or surfaced so they can be kept from happening again?

PRESERVING INSTITUTIONAL KNOWLEDGE

One of the tragic flaws of email is that not only is conversation locked inside a back-and-forth between two people, when in many cases it would be better shared “out loud,” but also that when one of the principals retires or leaves, the account is deleted. Whatever might have been there of value would have been difficult to extract, and now it’s gone forever. The person who leaves behind work narrated via a blog or through shared presentations, or via images captured during a tricky repair and posted to the work unit wiki, is helping to preserve institutional knowledge for those coming after.

IMPROVING PUBLIC PERCEPTION AND AWARENESS OF WORK AND EFFORT

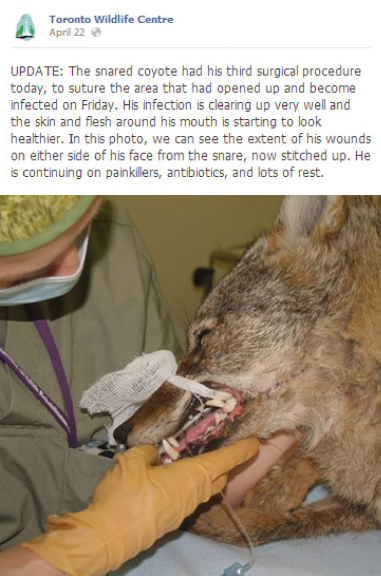

An organization successful at showing its work offers not just “What we can sell you” information but presents interesting accounts of work that that shows “what we do.” This can be especially useful for non-profit endeavors, those staffed with volunteers, and those supported by donations or tax dollars, as it says,”This is what we do with that money.” https://www.facebook.com/pages/Toronto-Wildlife-Centre/155768073655?ref=ts&fref=ts

The Toronto Wildlife Centre narrates its work, and generates a great deal of community engagement, via frequent Facebook updates. In April 2013 a post requesting donations for an injured coyote resulted in a huge community response and subsequent requests from the public for updates on the coyote’s condition. Since then, many people have been posting on Toronto Wildlife Centre’s page asking for updates on the coyote. Generating such a specific level of interest is an enormous boon in connecting with the public.

BETTER CUSTOMER SERVICE

Showing work can also result in enhanced service to customers. Christopher Groskopf says of the “mountain” of open source code he and colleagues developed during his time on the Chicago Tribune’s News Applications team: “More important than any individual project, we’ve found ourselves in the midst of an exploding community of news-oriented developers who are hell bent on using, contributing to, and releasing new open source code . . . This works for our industry because, with very few exceptions, none of us are in competition with one another. We can share code with the Washington Post, ProPublica, or the New York Times at absolutely no cost to ourselves. This collaboration allows all of us to serve our readers better.”

http://blog.apps.chicagotribune.com/2011/09/02/show-your-work/

REDUCING SPACE BETWEEN LEADERS AND OTHERS

Richard Edelman, CEO of the world’s largest independent PR agency Edelman PR, regularly posts to his first-person “6 AM” blog. Some posts are about business in general; others share insights gained via a personal experience; still others offer a frank revelation about decision making or activities that affect his organization and its workers. For example, a January 7, 2013, post titled “Paid Media—A Change of Heart” describes his reasoning for changing a long-held position. The blog—which invites comment—builds trust, supports an atmosphere of openness, reduces pushback and outcry, and helps everyone understand how the leader thinks. (See http://www.edelman.com/p/6-a-m/paid-media-a-change-of-heart/ for the post)

OTHER BENEFITS OF SHOWING WORK

- Supports recruitment. Showing work via public channels communicates “real” information about the company, the people, the work, and the ways in which workers spend their days.

- Disaster prevention/continue the flow. Narrating work answers questions such as:

- What happens if __________________ resigns or retires?

- What happens if __________________ is out sick?

- What happens if I transfer?

- What happens if I am out sick?

- Connecting with remote or scattered staff

- Lowe’s Companies believes in working out loud. In describing the Lowe’s “Open Leadership” initiative, Sandy Carter reports that the workers who offered the best tips turned out to be those located farthest from headquarters.

http://www.socialfish.org/2012/11/how-do-you-work-out-loud.html

- Enhances employee morale

- “One of the main intrinsic motivators is for people to see a purpose in their work. Visibility allows us to make connections to our coworkers, companies, and society at large.”

∼ Tullis & Crumpler, http://nextthingsnext.blogspot.com/2011/04/whats-vis.html

- Supports informal, social, and peer learning

- Supports the popular organizational talk about “collaboration”

ORGANIZATIONAL COMMUNICATION CASE STUDY: NASA’S MONDAY NOTES

Here is an overview from Dr. Roger Lanius of a very effective organizational communications system.

[A novel management approach] was pioneered at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) by its director, Wernher von Braun. This was the “Monday Notes,” a management tool he developed during the early 1960s.

Originated as a means of enhancing communication among managers, it was especially intended to deal with the communication gap while Kurt Debus, working much of the time in 1960-1962 at Cape Canaveral, Florida, was away from Huntsville, Alabama, where the Marshall Center was located. Simplicity was the key: no form was required, one-page maximum length, only header was the date and the name of the contributor.

Von Braun asked each of his senior managers to send him once a week a one-page, paragraph-style description of each week’s progress and problems. Submitted each Monday morning, it dealt with the previous week’s events and von Braun encouraged his reportees to offer totally candid assessments, with no repercussions for unsolved problems, poor decisions, and the like. This Monday Note became so successful as an informal communication tool that von Braun asked about two dozen other officials at MSFC to also send them in. Soon, those sending in notes were not just immediate subordinates, but also lab directors, project managers, and other selected key personnel. In many instances they were two of three levels below the Marshall Center director.

Von Braun read each note and wrote margin comments congratulating success, asking questions, making suggestions, or in some instances giving more negative feedback. After the review by von Braun, his secretary duplicated the entire package of Monday Notes and marginalia, and sent a set to each of those who submitted them.

These Monday Notes made possible important communication between leaders at MSFC. These became another tool—in addition to briefings, informal meetings, and memoranda—for the center director to keep informed of problems and progress. These provided easy and direct access to the MSFC director for managers two or more levels below; no middle-management edited the notes before they went forward. They also prompted the senior leadership at MSFC to pause once a week and reflect on what had been accomplished and to consider the problems to be resolved.

Everyone who has discussed the role of the Monday Notes at Marshall have concluded that the feedback function from the MSFC director was critical to their success as a management tool. It made possible a greater degree of vertical communication at the center, but it also facilitated horizontal communication between organizations, because each person sending a note got copies of everybody else’s, thereby learning what other organizations were doing.

Every week managers at MSFC stopped to read what their peers had communicated to von Braun and how he had responded. It served as a court of last resort in resolving differences between organizations at MSFC. The notes also sometime acted as legal briefs presented to an arbiter. Subordinates used the notes as a tool to place before von Braun their perspectives on difficult issues and to advocate their particular solutions. They knew they could get the attention of senior management and a resolution to a problem when raised in this manner.

The requirement to send a Monday Note also prompted many of the subordinate managers to improve internal communication in their organizations. Many required their subordinates to work up similar short notes for them, from which they prepared their inputs to von Braun. It forced virtually everyone in a leadership capacity at MSFC to pause once a week to reflect on what had been accomplished and to consider the problems to be resolved.

The Monday Notes illustrated two general principles in management:

- Made healthy conflict between organizations and persons at MSFC a realistic and useful management tool. The freedom (as well as the forum) to disagree was critical to the success of the organization. Disagreements that surfaced in the Monday Notes ensured that a variety of options and solutions were advocated. Evidence indicates that von Braun encouraged this type of conflict and was delighted that the notes were used to express it.

- The notes built redundancy into the management and communication system at MSFC. They ensured that all sides were heard. They created additional channels of communication both up and down the organization and across offices at MSFC.

Over time these notes became too bureaucratic—they were at one point institutionalized with forms—they ceased to be useful management tools. At that point they tended to be thought of as just one more report to file, and the time taken in doing it was time wasted in the accomplishment of the mission. Immediately, the quality of the notes fell, and they ceased to provide as much information to the MSFC leadership. Moreover, after von Braun left as director in 1971 his successor stopped making comments on the notes; they ceased to be useful for top to bottom communication.

- This communication system seemed to work best when it was a relatively informal, free-wheeling method of providing information directly to the center director, and back to all the key official. When it was formalized and institutionalized, the bureaucracy beat the liveliness out of the system. In that setting it became just one more form to be filled out, just one more report to be filed.

- The system also worked well when it had two-way communication direct to the top and direct back to the bottom in the form of marginal comments.

- The notes were also successful when they were freely distributed to all contributors.

- The notes also worked best when they allowed the raising of controversies and explanation of divergent positions on important matters within MSFC.

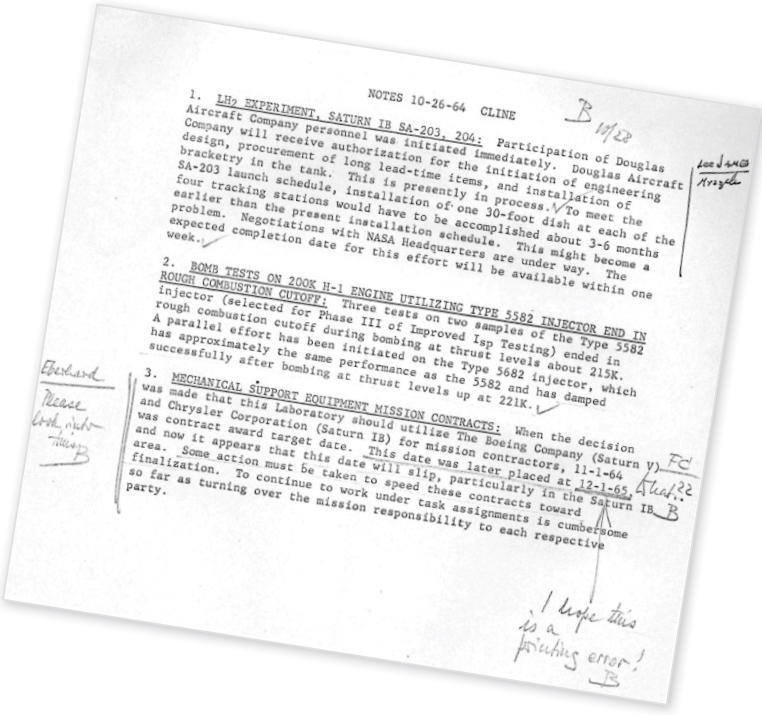

Here is an example of a Monday Note. The handwriting at the top is von Braun’s and the “B” denotes his review.

The Monday Notes are public record. They are archived and available for viewing at http://history.msfc.nasa.gov/vonbraun/vb_weekly_notes.html.

BENEFITS TO ORGANIZATIONS?

Showing work offers increased efficiencies, the possibility of innovation and increased ability to improvise, and promises correction of longstanding deficits in organizational communication. Organizations seeking to leverage the potential will find themselves more flexible and agile, and will be better positioned to respond to exceptions, turnover, and sudden changes.

Write something: “The published word is a declaration of membership in that community and also of a willingness to contribute something meaningful to it.” Writing creates a deliberateness and encourages reflection.

GAWANDE, BETTER