2. The True Nature of Six Sigma: The Business Model

With Randy Perry

This chapter will cover the inherent nature of Six Sigma and most of the necessary elements of an effective Six Sigma launch at a business level. Although Six Sigma has a reputation of being a manufacturing program, it is much more complex. Essentially, Six Sigma is about streamlining and money. This chapter is aimed directly at you, a leader who wants to dramatically impact the performance of his or her organization very quickly. This chapter will help you clarify the potential business impact of Six Sigma and will give you a general sense of what needs to be done to launch Six Sigma quickly and effectively. The elements and methodologies presented in the chapter will be covered in more detail in later chapters.

While focusing on a fast Six Sigma launch, however, we must never lose sight that the real purpose of your organization is to make money.

The Business Model

How can you make a lot of money consistently over the long term? Now that is the question! The answer may lie with one of the most effective CEOs of our day, Larry Bossidy. Larry Bossidy (with Ram Charan) in his book, Confronting Reality, presents a unique business model that links four components:

These three components are linked into a dynamic system that produces new business models with which to move your business smoothly into new markets and new products. Bossidy and Charan state, “Linking and iterating the financial targets, external realities, and internal activities, and searching for the right mix in each of the three components of the business model determines the accuracy of the final product.” You will make money by effectively linking your internal activities to the external realities and setting appropriate financial targets.

This fresh approach to facing the realities of today’s competitive marketplace happens to represent our approach to Six Sigma. It’s no coincidence that, in 1994, Larry led the best launch of a Six Sigma initiative since Motorola’s launch in 1987 and that I base this book largely on that deployment. This chapter presents the business case for Six Sigma, and we’ll use Larry’s model as a basis. You will see how Six Sigma allows you to effectively link the three components of the Bossidy model to ensure that you hit your financial targets year after year.

I met with a new president of a chemical company to talk with his leadership team about the benefits of Six Sigma. He had recently arrived from AlliedSignal, and he explained to his leadership team, “Before Six Sigma, we developed our annual operating plan and then executed the best we could, but hoped at the end of the year we would have met our goals. We deployed Six Sigma, and I not only didn’t have to hope to meet our goals, but I sometimes got up to 2x my usual end-of-the-year bonus.” In fact, in a classic case study, 3M’s CEO, Jim McNerney, used Six Sigma as one of his first steps to linking the three components soon after he arrived at 3M.

Assessing External Realities

First, let’s look a little closer at Larry’s model. The first component, assessing the external realities, looks at the business and economic environment in which you currently compete. You will assess four elements, as follows:

• The broad business environment

• The financial history of your industry

• Your customer base

• Root-cause analysis

In reality, these four assessment elements provide the inputs of systematically collected market, industry, and customer data (with the attractive option of using Six Sigma–based marketing tools and roadmaps) and the output of a new business model based on intuition and judgment. Because you are deep into the complexities of the marketplace, there is no guarantee that the models you develop are the right ones with which to move forward. But by assessing the external realities systematically and iteratively, you greatly improve the probabilities that your leadership will understand what your company needs to do to be competitive.

Setting Financial Targets

Once you determine what needs to get done strategically, you then set financial targets linked to the external realities. These targets include a subset of the usual suspects in the financial world:

• Operating margins

• Cash flow

• Return on capital

• Revenue

• Return on investment

The financial targets you set will depend upon your external realities. For example, a company might demonstrate mediocre operating capability, so financial metrics addressing productivity may have more aggressive goals than those addressing growth. You might set 20% improvement targets on operating margins and cash flow and 10% improvement targets on revenue.

Once financial targets are identified and goals set, Six Sigma really starts. Clear measurable metrics and targets represent the foundation of Six Sigma. The old adage, “what gets measured gets done,” applies here. With financial metrics driving your Six Sigma program, all activities, if prioritized properly, will directly affect your company’s performance.

The Nature of Six Sigma

Six Sigma is focused on process improvement. Anything your customers see from your company are the outputs of a set of business processes. In fact, you could say that a Six Sigma company views poor results as symptoms of poorly designed processes that produce process errors. Six Sigma methodologies provide you the quantitative understanding of the relationship between the process outputs and the process inputs. The basic formula is simple: The output of a process is a function of a set of the inputs of a process (Y = f(x’s)). But of course, this is Six Sigma, so I have to produce some kind of formula. So we’ll use:

Y = f(x1, x2,...,xk)

Where Y is the output and the Xs are the inputs. We would say, “Y is a function of the Xs.”

We would call our selected strategic financial metrics (e.g., operating margins, cash flow, revenue) our “Critical Ys.” Examples of some of the output/input functions would be as follows:

• Y(operating margins) = f(revenue, product costs, business costs)

• Y(cash flow) = f(profits, working capital)

• Y(return on capital) = f(volume, average selling price, discounts)

• Y(revenue) = f(volume, average selling price, discounts)

• Y(return on investment) = f(profit, investments, net assets, asset turnover)

You may argue with the inputs, but you get the point. Every financial metric is driven by a set of inputs, and these inputs can usually be tracked back to operational processes. We’ll refer to each of the preceding Ys as Critical Ys because they are financial metrics that drive the success of the company. If you understand and control the variation of the inputs, you control the variation of your Critical Ys (outputs).

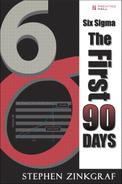

Let’s take one of the preceding financial metrics and move a little farther down the Six Sigma path. Let’s pick the one that is near and dear to our hearts, cash flow. For the process output, or our Critical Y—cash flow—we might have an equation like Y(cash flow) = f (profits, working capital). The output, cash flow, the Critical Y, is a function of the inputs, profits, and working capital.

The next step is to consider the inputs of profits and working capital as second-level outputs, or Little Ys. We then identify and prioritize which operational inputs have the most influence on each of profits and working capital. Some example inputs for the Y(profits) would be the following:

• Manufacturing yields

• Cost of poor quality

• Invoice to cash

• Supplier cost variances

Some example inputs for the Y(working capital) might be the following:

• Manufacturing yields

• Product cycle time

• Work in progress levels

• Finished goods inventory

• Raw materials inventory

In the Six Sigma world, we would then analyze the inputs to the process outputs, Y(profits) and Y(working capital), and identify which process inputs drive the variation in these two process outputs and optimize them. By understanding and optimizing the inputs, we will then control the variation and optimize our outputs. With the right work in the right places, we will make huge impacts on profits and working capital, which will in turn have a significant and positive impact on cash flow (our Critical Y). Figure 2.1 shows the relationships between the Critical Y(cash flow) and the Little Ys (profit and working capital). And finally, I’ve mapped the Little Xs into the Little Ys. The point of all this? Well, we see several operational inputs we might address to improve cash flow. We notice that if we improve manufacturing yield, we would improve both Little Ys of profit and working capital. If we do some baseline measurements, and we find we have a lot of room to improve yields, then a set of Six Sigma projects addressing yield would be valuable to the company. As we improve yield, we improve both profit and working capital and, in turn, we improve cash flow (our strategic financial target).

Figure 2.1 The Six Sigma input/output model depicting the Critical Y (strategic financial target), Little Ys (inputs to the Critical Y), and Little Xs (operational targets).

Likewise, if we find we are inefficient in the way we manage our work in progress and we have a lot of potential to improve there, we would launch a set of projects around improving work in progress depending on Lean manufacturing methods. These projects will be a combination of Lean and Six Sigma techniques. By improving our work in progress levels, we directly impact working capital (our Little Y), which in turn impacts cash flow (our Critical Y).

Linking Internal Activities

Bossidy’s model includes the third component: internal activities—the scan of the environment. Now that you have assessed the external realities and your gaps in the market and have created a linked set of financial targets, you are ready to execute the new business model by linking your internal activities. The elements of this component encompass the following:

• Strategies

• Operating activities

• People selection and development

• Organization

These internal elements must be clearly linked to the external realities. The strategy is the document that shows the alignment between the external realities, the financial targets, and the set of elements including operating activities, people, and organization.

Given a solid strategy (the prerequisite to launching a successful Six Sigma program), Six Sigma directly impacts operating activities and people selection and development. The companies that have been successful in deploying Six Sigma have been given options to defining new strategies. Operating activities as defined by Larry Bossidy include the initiatives and processes “that enable your business to reach the desired financial targets and execute strategies, such as product launches, sales plans, and measures to improve productivity.”

Because Six Sigma was born out of manufacturing in Motorola in 1987, Six Sigma is notorious for streamlining and optimizing manufacturing processes. But Six Sigma also has a fine history in impacting business processes and new product and services development, as well as sales and marketing. In fact, every operating area in your company will have a special Six Sigma roadmap to use to make their part of the company great.

Bossidy suggests, when evaluating your strategy, you answer the questions: “Do you have the right people to pull off the introduction of new initiatives? Are they properly deployed—are the right people in the job?” Six Sigma has long demonstrated its capability to develop the future leadership of companies that use it. In fact, Six Sigma launches in AlliedSignal and General Electric spurred the creation of new corporate positions throughout the corporate world today. There are entire headhunting companies and web sites dedicated to finding Six Sigma Master Black Belts, Black Belts, and Green Belts. These Belts have learned the art and science of process improvement through completing important projects successfully.

Again, Six Sigma is process focused. Your company is defined by hundreds of processes—a legal department alone in a very large company identified over 40 processes they manage. Your customers see only the results of how efficient and effective these processes are. If you are not focused on systematic process improvement, you will ultimately lose in the marketplace to competitors who do. So, to rephrase Larry’s business model in terms that are a bit more Six Sigma friendly, we can say that the growth of your company depends on how effectively you link the following:

• Dynamics of your industry

• Corporate strategy and organization

• Policies and procedures

• Product or service technologies

• Operational processes

• Business processes

Six Sigma directly impacts the last three: technologies, operational processes, and business processes. Understanding the dynamics of your industry and developing a corporate strategy and organization to address those dynamics tells your organization what to do. Six Sigma shows your organization how to do it.

So, Six Sigma is like having a corporate personal trainer. Six Sigma will help quantitatively define business goals and achieve them, will bring the necessary discipline to process problems, and will align your company’s resources to achieve specific goals and—most importantly—convince people these goals can be achieved.

Focusing On, Finding, and Delivering the Money

Now that we’ve defined the business model within which we will work, let’s now focus on the real important issue of making money. We will focus on a three-step process:

Focusing on the Money

A Six Sigma program, launched correctly, will provide a discipline throughout the organization around the powerful concept—making money is a key objective. By creating this focus on money, you will see behaviors changing as people consider their actions in relation to what goes to the bottom line of the balance sheet.

Finding the Money

Six Sigma provides a methodology and toolkit with which to find opportunities for financial improvement. Starting with your financial targets, your organization will identify and prioritize projects that are linked to these targets. The result of this process produces a set of high-impact projects that are clearly linked with your financial targets and ultimately with the external realities.

Delivering the Money

Now this is where Six Sigma really shines. Once the set of high-impact projects are identified, they will be chartered and your leadership will assign Black Belts or Green Belts (Belts) to drive these projects to completion. Six Sigma provides these Belts with structured methodologies with which to execute these projects and deliver the financial value to the company.

Your financial people will be heavily involved in validating the financial impact of each completed project, and you will have developed an infrastructure of Champions and Master Black Belts to ensure a high project-completion yield. Statistically valid data will drive the decisions about financial impact to be data based.

To give you an example of the financial impact of a large set of projects, AlliedSignal delivered over $880 million in pretax income within the first two years of the program. This was based on the work of 1,200 Black Belts and 7,000 Green Belts. That was almost equivalent to adding a $4.5 billion-per-year business to AlliedSignal’s portfolio without any of the associated capital.

The engineered materials sector of AlliedSignal—a $4 billion-per-year business—delivered over $200 million in pretax income with a cadre of about 300 Black Belts and 800 Green Belts. The Black Belts were averaging about $350K per project and the Green Belts were averaging about $75K per project.

In the process, AlliedSignal created some 8,000 stars—people who were given great projects with the resources and commitment—who went out and made a huge impact on the company. AlliedSignal gave motivated people the opportunity to release their creative problem-solving potential and allowed them to see the results of their efforts hit directly on the bottom line. One 23-year-old Black Belt delivered 3 cents per share with one project! With these three process steps—focusing on, finding, and delivering the money—let’s take a look at each step in more detail.

Focusing on the Money

In recent years, Six Sigma has been associated with quantitative improvements in growth and productivity. But, Six Sigma hasn’t always had the reputation. In its early years with Motorola, Six Sigma was primarily associated with systematic improvements in product quality. At this point in our discussion of Six Sigma and the focus on money, a quick review of the evolution of Six Sigma from 1987 to the present would provide some context to the following sections.

Six Sigma Evolution

Motorola. Historically, Motorola developed Six Sigma in 1987 to eliminate process defects. As a manufacturing manager with Motorola in those days, I can say we were evangelistic about preventing defects. We operated with the goal of reducing our defects by 68 percent year over year (equating to a 10x improvement every two years). In fact, my defects-per-unit (dpu) trend charts where shown monthly to Motorola corporate operations reviews. The metric and visibility were perfectly clear.

If you were not showing improvement in your dpu trend charts, you had very interesting meetings with the plant manager. However, we rarely evaluated the direct business impact of these defect elimination projects. We just believed in our hearts that removing defects allowed us to produce products better, faster, and cheaper.

That was generally the case because we saw countless dramatic case studies addressing business improvement. But there were instances when we would work on a project that might eliminate defects within a certain process, but these activities would sometimes have little or no effect on overall business.

AlliedSignal and Beyond. Six Sigma changed from the focus on reducing defects to focusing on the money that resulted from the impact of two men, Richard Schroeder and Larry Bossidy. Rich launched Six Sigma for Asea, Brown, Baveri (ABB) in the U.S. in 1992. ABB is a large global company with a strict bottom-line focus. Rich had been a driver of Six Sigma during the Motorola heydays, but learned quickly the usefulness of focusing Six Sigma on bottom-line results.

Rich then moved to AlliedSignal in 1994 to launch Six Sigma for Larry Bossidy. Larry, coming from the numbers-oriented GE, appreciated the focus on the money and drove Six Sigma, with the help of Rich, to ensure a significant impact on earnings per share. Stock prices went from the mid-$30s in 1995 to the mid-$70s in 1997, and AlliedSignal delivered almost $1 billion of pretax income in the first two years. The next thing you know, Larry Bossidy tells his friend Jack Welch, and GE launches a huge initiative. Six Sigma has never been the same.

Six Sigma and TQM. A question about Six Sigma—How is it different from Total Quality Management (TQM)?—pops up frequently. TQM, developed in the 1980s to address quality, led a very large number of companies that were dissatisfied with the results. In fact, surveys done in the late 1980s and early 1990s by Arthur D. Little, McKinsey & Co., Ernst and Young, A.T. Kearney, and Rath and Strong indicated that for every company pleased with its TQM results, two other companies were not. The TQM initiative usually took about three years to launch and still didn’t make much difference in organizational performance.

Unfortunately, many companies sponsoring TQM fell into the trap of confusing activity for results. Projects were often selected to drive “Quality for quality’s sake.” Thousands of people were trained in very basic quality tools and thousands of projects were completed. Award ceremonies were ubiquitous. Larry Bossidy referred to TQM as “mugs and hugs,” and didn’t want to have anything to do with it.

Although Six Sigma uses many tools common to TQM, it is quite different. Some of the ways in which Six Sigma differs from TQM include the following:

• Linking improvement activities to the external realities, financial targets, and strategy

• Focusing externally on the customer and markets

• Focusing on and delivering money and financial results

• Selecting projects based on delivering financial benefits

• Creating an organization that will solve complex process problems with sophisticated tools

• Providing specialized improvement roadmaps for specialized problems

• Delivering of quick results

One senior leader put it best: “Before TQM, we made poor-quality products that didn’t sell. After TQM, we made high-quality products that didn’t sell.” Just remember Motorola’s decision to stay with their high-quality analog cell phones and then watched as the digital market went right by them. Because TQM didn’t link activities to the strategy and the critical business processes, it never quite hit the mark.

Six Sigma: Focus on Money

Six Sigma has money as a primary focus. But consider what that means. Your company can create money in three ways—bottom-line growth (productivity), top-line growth (growth), and freeing up cash. Therefore, all Six Sigma projects should be linked to the organizational strategy and be directed at hitting growth targets, cash targets, and productivity targets.

A comprehensive Six Sigma program includes specialized process improvement roadmaps to be applied to different classes of process problems. Designing a new product or service, for example, requires a radically different approach when compared to optimizing a manufacturing process. Solving problems in transactional processes (finance, human resources, sales) requires a different tool set than solving manufacturing process problems.

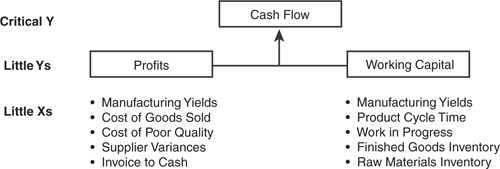

For projects directed toward improving productivity, the operations-oriented DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, and Control) roadmap is used. For projects directed at growth, the roadmaps associated with DFSS (Design for Six Sigma) and the MSS (Marketing for Six Sigma) are used. Figure 2.2 depicts the linkage from the strategic plan to the cluster of projects in growth and productivity, and then to the actual Six Sigma methodologies to apply to the projects.

Figure 2.2 How Six Sigma links strategy to methodology through financial targets.

Six Sigma projects, once identified and prioritized, will be chartered. The charter is a contract between the project manager (Black Belt or Green Belt) and his or her organization. The charter defines time lines, expectations, metrics, and resources, and should have the blessing of a financial analyst. The organizational leadership will evaluate the need for Six Sigma projects to support the strategic plan in the short, medium, and long term. As the business drives for long-term growth, DFSS and MSS become critical methodologies for delivering value and hitting financial growth targets.

Creating a strong focus on money is the first prelaunch set of activities of a successful Six Sigma launch. Understanding, based on your external realities, where you need to deliver value will drive financial targets and business areas within which you will focus your Six Sigma efforts. The next step is the most difficult step in launching Six Sigma—finding the money.

Finding the Money

There is money to be made in every corner of your organization. Every function will contribute to productivity, and many functions are involved in driving growth. Your company is comprised of hundreds of processes, each of which creates defects, and adds costs and time due to non-value-added process steps. However, trying to solve all your problems simultaneously will only overload your organization, and you’ll end up like the old TQM companies—generating a lot of activity with no results to show for it. The most difficult thing to do in any business is to find the relatively few projects that will generate the biggest results strategically.

Value Mapping. Selecting critical processes, mapping them, and then setting the baseline performance for quality, cost, and cycle time, you will see clearly where you need to work. We’ll call this procedure value mapping. We saw in a previous section how we move from your strategy to a set of financial targets to potential areas on which to focus. Looking at Figure 2.1, we dissected the financial target of cash flow into several components:

• Cost of Goods Sold

• Cost of Poor Quality

• Supplier Variances

• Order to Cash

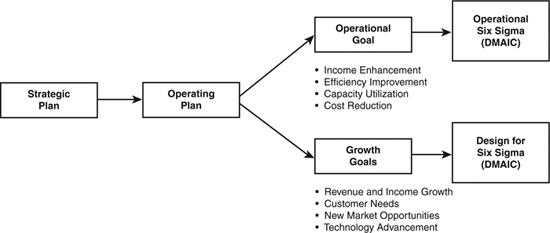

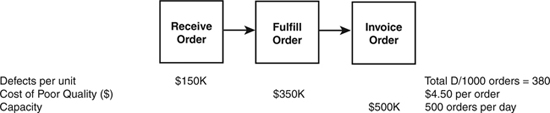

For this example, we’ll pick a process that is linked to Order to Cash—Order to Invoice. Let’s look at the value map in Figure 2.3. This might be a typical manufacturing process or a transactional process. I’ve used the Order to Invoice process as a high-level process for this example. We’ll keep things simple and say this process only has three steps. We would send out a team to capture basic performance data (quality, cost, and cycle time).

Figure 2.3 Order fulfillment process with three steps showing basic quality, cost, and cycle time measurements.

Now, this is exactly the methodology used with the AlliedSignal engineered materials sector in 1994. Plant managers took two to three weeks to produce the baseline data they needed to complete their value maps. On inspecting the value map in Figure 2.4, we see that the first step, receiving the order, has very poor quality. If this company completed a successful Six Sigma project, it stands to save $150,000 per year.

Figure 2.4 Order fulfillment process with three steps showing the estimated financial impact of three projects.

We also see that the second step, fulfilling the order, has the highest cost of poor quality. For every 100 orders, this organization loses $450.00. And, finally, we see that the third step, invoicing the order, has the lowest capacity, with only 500 orders per day. Any improvement in capacity at this step will lead to an overall capacity improvement for the entire process. So, by committing to and completing projects to improve quality in Step 1, cost of poor quality in Step 2, and capacity in Step 3, the company stands to bring some $1,000,000 to the bottom line. These problems have probably existed for years, but they just didn’t make the leadership radar screen until they put some performance numbers and financial numbers to them.

So, it would appear that we have three good projects on our hands. However, there is one more step here. The organization will now work closely with their financial analysts to investigate the potential business impact of each project. Figure 2.4 shows the results. The projects attacking cost of poor quality and capacity are estimated to bring $350K and $500K to the bottom line, respectively. These would most surely end up on a Six Sigma project list. The project attacking quality is estimated to bring in only $150K, which is marginal when compared to the other two projects. Depending on resources and other projects identified, the quality project may or may not show up on the final list.

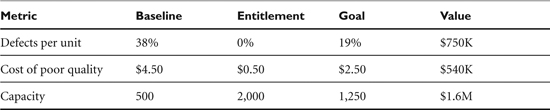

Process Entitlement and Goals. A key concept in driving for aggressive goals turns out to be a concept called entitlement. Entitlement represents the best theoretical outcome for any process metric. So, in our preceding example, the process entitlement for defects-per-unit would be theoretically zero. The entitlement for cost of poor quality would be very close to zero—there may be some cost built in for destructive testing and such. The entitlement for capacity would depend on assessing the total value-added time versus the non-value-added time, but would probably be much greater than 1,200 orders per day—let’s say for the sake of argument, the entitlement for capacity is 2,000 orders per day.

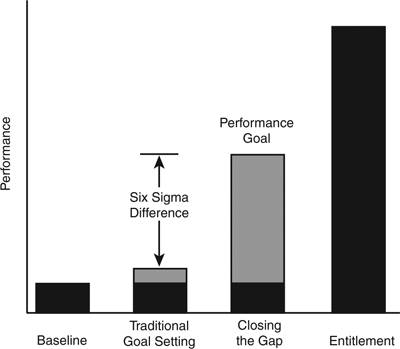

To set Six Sigma goals, an aggressive approach is to move the process from baseline performance to 50% closer to the entitlement. For example, Table 2.1 shows the baselines and entitlements for the metrics in our invoicing process. The defects-per-unit goal would be halfway between the baseline, 38/100, and entitlement, 0/100. The goal calculates to be 19/100. You know the project addressing defects-per-order is done when 19/100 defects per order is accomplished. Figure 2.5 shows the concepts of baseline, entitlement, and goal setting. This figure shows the difference between a Six Sigma goal—moving quickly toward entitlement—and the usual corporate mode of goal setting—looking at a 10%–20% improvement.

Table 2.1 Chart Showing Process Baselines, Entitlements, and Goals for the Invoicing Process

Figure 2.5 Process goal setting using baseline and entitlement. The goal closes the gap between baseline and entitlement by 50%.

The concept of entitlement is valuable psychologically as well as for goal setting. Entitlement allows your leadership team and you to see clearly what you should be able to accomplish as you move toward perfection. Fred Poses, CEO of American Standard, was instrumental in launching a great Six Sigma program into AlliedSignal’s engineered materials sector. He told his leadership team at his new company, American Standard, that the most important concept in Six Sigma to him was entitlement.

Measuring the gap between current performance and entitlement allows your company to realize the possibilities for process improvement. It has been said that, “Knowledge of the possibilities is the first step to passion.” Understanding clearly how good your company could be is the spark with which you will ignite a terrific launch of Six Sigma.

This concept actually applies to golf. How can a sport that’s so frustrating be so popular around the world? I’m convinced that golf’s popularity is related to the idea that each golfer catches a periodic glimpse of his or her entitlement in playing golf. That one excellent drive, the miraculous chip shot, and the long putt all provide reinforcement to the golfer on just how good he or she could be. He or she becomes a passionate golfer even though the actual performance isn’t close to the entitlement.

Analyzing Profits

Everyone in any business finds profit margins very interesting. Dissecting profit margins analytically produces some great places to find money. We can look at profit quantitatively with this simple formula:

Profit = Revenue – Cost

That’s simple enough. But we can take this equation one step further to gain additional insights into where to look for money:

Profit = [Volume × (Price − Variable Cost/Yield) − Fixed Cost] × (1 − Tax Rate)

This formula is more complex, but captures the variables that are heavily influenced by variability—variable cost, yield, and fixed cost. As variability is removed from business processes, those three variables improve and directly affect profit. A more effective system will positively improve price and volume because of improvements in quality and functionality of products or services.

So, projects can come from some of the following areas:

• Increasing sales volume

• Increasing sales price

• Reducing variable cost of production or operations

• Improving process yield

• Reducing fixed cost

• Reducing tax rate

Looking at the preceding, Six Sigma projects can therefore be found in manufacturing, technology, marketing, sales, administration, support, and all other areas of the business. Some great examples of Six Sigma project clusters include the following:

• Reduce sales price errors

• Improve capacity productivity

• Optimize mix of products sold

• Increase price through good product design

• Discounts

• Reduce special sales allowances

• Reduce contract discounts

• Cost of sales (material, labor, overhead)

• Improve product flow

• Lower supplier costs

• Improve quality in production

• Improve quality in suppliers

• Improve payables terms

• Reduce inventory owned

• Redeploy assets

• Improve equipment uptime

• Warranty

• Improve manufacturing processes

• Improve source of components

• Reduce testing

• Streamline warranty process

• Improve warranty forecasting

• Eliminate abuses of warranty system

• Improve design process to improve process and product quality

• Fix issues quickly to satisfy customers

• Engineering expenses

• Reduce time to develop a product or service

• Reduce required product testing

• Improve cycle time of engineering change notices without impacting quality

• Better utilize partners and suppliers for better designs

• Improve technology development

• Reduce discounts

• Eliminate low or no margin businesses

• Improve capacity productivity

• Improve processes for communicating product or service volumes

• Improve forecasting process

• Improve voice of the customer data collection

• Administrative expenses

• Improve administrative flows

• Reduce defects in administrative processes

• Reduce depreciation, taxes, and insurance

• Eliminate central inventory holdings

• Reduce the number of suppliers

• Interest

• Improve management of cash

• Reduce inventory levels

• Improve receivable process

• Improve payable process

• Minimize fixed asset investments

• Taxes

• Optimize tax process to obtain tax advantages

• Prevent overpayment of taxes

• Optimize inventory levels

Many other projects show up when we look at our “hidden costs” within the business. These costs are a result of poor performing business processes. For example, flaws in new product development show up in delayed commercialization and delayed “kills” on new product projects, both of which lead to missing your growth goals. Your poor sales process will lead to lost orders and longer lead times. Your payables, receivables, and inventory process, if not efficient and effective, lead to cash flow issues.

We will be discussing in further detail the process of selecting the right projects to move you forward in your strategic actions. But once a good set of projects is identified and quantified financially, the next step is to deliver the money.

Delivering the Money

Now comes the fun part—delivering the money. You have just spent a lot of time understanding your external realities, creating a strategy to take the offensive, and you’ve set some financial targets to reflect your strategic goals. You’ve then assessed your business processes and identified a set of important project clusters—areas that one or more projects will address.

Now, with the help of your Project Champions, your organization will identify specific projects that are linked to your financial targets and strategic goals. Each function in your organization will assign projects to Six Sigma Black Belts or Green Belts, and these project managers will be accountable for the completion of the projects. Your financial group will bless each project to ensure that financial impacts are realistic and can be achieved. Now the bottom-line focused Six Sigma starts. Your Black Belts and Green Belts will be given training in the roadmap and tools specific to the need of their projects.

For example, a marketing Black Belt will attend Marketing for Six Sigma training and learn the Marketing Six Sigma roadmap and tools. Your product development people will do the same with Design for Six Sigma (DFSS). Your manufacturing and transactional people will attend DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, and Control) training in process improvement. Some of your organization will attend Lean Enterprise training or integrated Lean Sigma training.

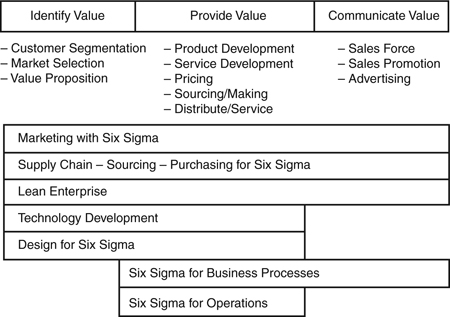

In fact, there are over 20 different Six Sigma roadmaps that are available to address just about any strategic process-oriented problem you may have. Figure 2.6 depicts a typical business with three functions: to identify, provide, and communicate value. You will see seven Six Sigma macro roadmaps.

Figure 2.6 Six Sigma macro roadmaps to support the entire business.

These roadmaps allow you to take Six Sigma into virtually every part of your company. The challenge of launching a Six Sigma program is to determine how to phase the seven roadmaps into your company while leveraging the right roadmaps on the right strategic goals.

An example of one roadmap, the DMAIC roadmap (sometimes known as the operations roadmap), consists of the following steps:

• Define: Identify the scope of the problem and estimated benefits of the solution.

• Measure: Measure the current variation of the performance data included in the problem.

• Analyze: Find potential sources of variation of the performance data.

• Improve: Verify, control, and optimize the sources of variation of the performance data.

• Control: Establish a system of controls to manage the gains of the solution.

So, each roadmap is a system made up of a series of discrete steps that lead to a solution to the problem. Each roadmap is set up to make decisions based on facts and data. Each roadmap drives toward delivering money to the bottom line.

In delivering the money, you can plan on training between 0.5% and 4% of your population as Black Belts and between 10% and 30% of your population as Green Belts. The percentages could easily be higher depending on the broadness of the scope of your Six Sigma deployment. Each Black Belt should deliver between $250K to $1.2 million per year and each Green Belt should deliver between $100K and $500K per year. Each completed project should have a financial signoff.

As you might have guessed, while Six Sigma is highly effective in delivering money, you can still expect a huge commitment of your own time and the time of your senior leaders to create the infrastructure and processes to support your new Six Sigma efforts. The remainder of this book will provide you with details into every milestone you must achieve to launch a Six Sigma program in 90 days (or less).