15. Leading Six Sigma for the Long Term

With Dick Scott

We have been focused thus far with successfully launching a company-wide Six Sigma deployment within 90 days. Your Six Sigma program has now been successfully launched. You must now implement the systems and processes needed to effectively lead the deployment over the long term. This is a critical step toward ensuring that you achieve a culture change and that Six Sigma becomes how you do your work. Failing to implement these required processes and systems is a sure guarantee that Six Sigma will simply become another flavor of the month.

The purpose of this chapter is to identify and clarify a leadership roadmap for Six Sigma. The Six Sigma leadership roadmap will intensify and institutionalize your Six Sigma program and make Six Sigma a model initiative. The deployment roadmap, while paying attention to transforming your company, has been based on John Kotter’s eight-stage process of leading change. We are now ready to work on Stage Seven (consolidating gains and producing more change) and Stage Eight (anchoring new approaches in the culture).

Kotter’s Stages Seven and Eight

Consolidating Gains and Producing More Change. Pending a successful launch that produces dramatic early results, the next step is to grow the Six Sigma initiative with other focused efforts. For example, AlliedSignal focused on manufacturing operations during the first year and then added emphasis to growth by launching Design for Six Sigma (DFSS), and later started Transactional Six Sigma. Each new effort has the same accountability to the financial targets as the first project.

This stage evolves Six Sigma to include all parts of the company. Usually, the first evolution for U.S.-based companies is to launch Six Sigma in Europe and Asia. As Kotter quotes, “Culture changes only after you have successfully altered people’s actions, after the new behavior produces some group benefit for a period of time, and after people see the connection between the new actions and the performance improvement.”

People will see over and over again Black Belts accounting for $250,000 to $1,000,000 to the bottom line, project after project. They will either want to be on a project team or be trained as a Black Belt. Simply, as stock values continue to go up, change becomes easier.

This stage prepares the organization to launch future changes to match the company vision. By really nailing your Six Sigma initiative, you will have lived through a change roadmap that will work for any future change you want to drive, regardless of what the change addresses. Learning how to effectively launch a change and then institutionalize it is a new core competency for your company.

Anchoring New Approaches in the Culture. After the Six Sigma deployment is successful, you have to start thinking about what you need to do to make sure the company’s doing Six Sigma 10 years from now. Even the Six Sigma pioneer, Motorola, which launched Six Sigma in 1978, found Six Sigma lacking in the late ’90s. You must understand that the change initiative—in this case, Six Sigma—has to be reviewed at least every three years with respect to reenergizing the initiative.

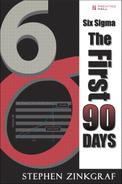

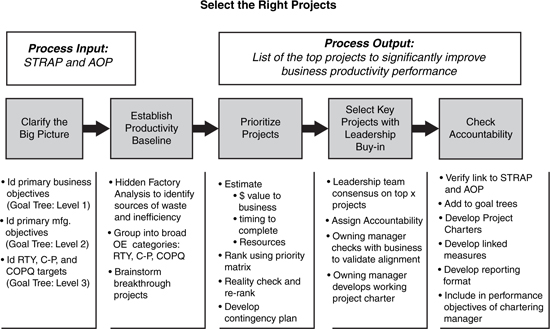

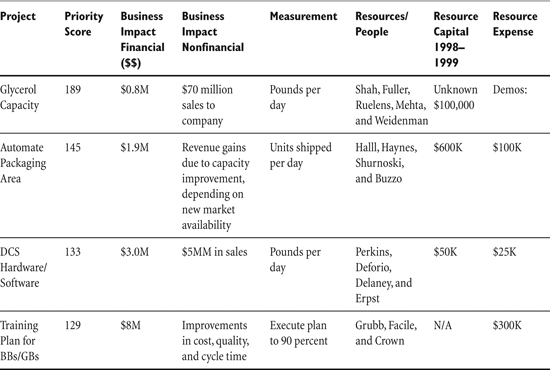

Anchoring an initiative is directly related to the infrastructure and systems developed to support the initiative. Fortunately, the very nature of Six Sigma addresses developing streamlined processes and systems. So, the systems developed to support Six Sigma should be user friendly and work quite well. For example, one method used by Fred Poses in AlliedSignal’s early deployment days was to include each division’s Six Sigma project plans in the annual operating plan. This straightforward anchor ensured that every plant manager knew how important Six Sigma was to Fred. An example of this method is displayed in Figure 15.1.

Figure 15.1 An example of manufacturing plants adding their major Six Sigma projects to their annual operating plan.

Six Sigma must have something going for it judging by the number of CEOs who left Six Sigma companies for a non-Six Sigma company and then introduced Six Sigma to that company. This list is long, which indicates that Six Sigma should not be difficult to anchor in the culture, but methods of anchoring Six Sigma will be considered in your deployment plan.

Five Steps to Leading Six Sigma

Let’s talk about the five steps to leading Six Sigma. The most common question that arises when I talk to companies that are pondering Six Sigma is, “What are the most common failure modes in deploying Six Sigma?” The answer is found in Kotter’s eight stages. Missing one of those stages or doing one of those stages poorly is a sure recipe for failure.

The five-step process I will show you proactively addresses some of the common failure modes. This simple (elegant) leadership roadmap will ensure the long-term success of your Six Sigma program. All your managers should commit this roadmap to memory.

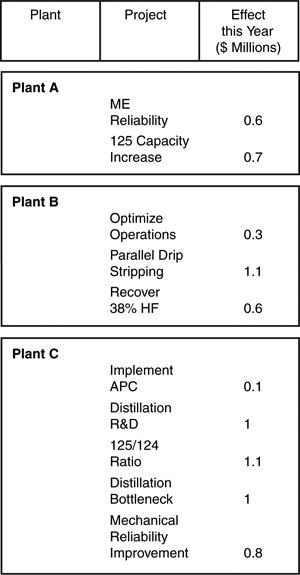

By following this roadmap, you will be assured that your Six Sigma program will be anchored in your culture. Six Sigma becomes a documented business process rather than an extensive training program. You will have to train people in your company to apply Six Sigma principles to serious projects, and you have to train your leaders to lead Six Sigma effectively. The five-step process consists of these steps, as seen in Figure 15.2:

1. Select the right projects.

2. Select and train the right people.

3. Plan and implement the Six Sigma projects.

4. Manage Six Sigma for excellence.

5. Sustain the performance gains.

Figure 15.2 The Leading Six Sigma leadership roadmap—inputs and outputs.

The preceding five steps represent process steps. The process inputs capture the key inputs needed to define the business needs. Recalling Larry Bossidy’s three-element business model (external realities, financial targets, and internal activities), the inputs refer to the business strategic plan (STRAP) and annual operating plan (AOP) to define clear operating objectives. Add financial targets and information about your customers and the market, and you have the start of a complete set of process inputs. Figure 15.2 provides a schematic view of the leadership roadmap, including its inputs, process steps, and output. We will now cover each process step in detail.

Several of the key elements of this roadmap have been covered in detail in earlier chapters. Strategic process inputs, annual business goals, and targets are discussed in Chapter 2, “The True Nature of Six Sigma: The Business Model,” and Chapter 5, “Strategy: The Alignment of External Realities, Setting Measurable Goals, and Internal Actions.”

Step 1: Select the Right Projects is discussed in Chapter 9, “Committing to Project Selection, Prioritization, and Chartering.”

Step 2: Selecting and training the right people is examined in Chapter 11, “Selecting and Training the Right People,” and Chapter 8, “Defining the Six Sigma Infrastructure,” covers the roles and responsibilities of those people.

Step 3: Plan and implement the Six Sigma projects is covered in Chapter 8 and Chapter 9.

Step 4: Manage Six Sigma for excellence is discussed in Chapters 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 13, 14, and 16.

Step 5: Sustaining the performance gains is discussed in Chapter 6, “Defining the Six Sigma Program Expectations and Metrics.”

Process outputs: make the numbers is also addressed in Chapter 6.

Six Sigma Leadership Step 1—Select the Right Projects

Selecting the right projects is the key step in institutionalizing Six Sigma. Meeting the process output of making the numbers is directly and strongly related to the aggressiveness and discipline of project selection. Performance breakthrough is tracked directly to the projects that produce the breakthrough. Chapter 9 gives you the details on identifying and prioritizing projects. For Six Sigma to be wildly successful, the deploying company must develop a clear process for accomplishing the selection of the right projects every year.

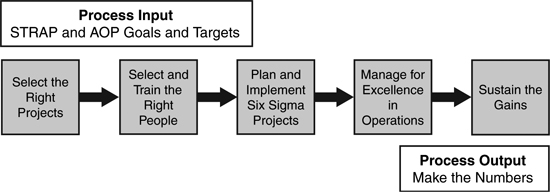

Selecting the right projects begins by making certain that everyone involved in Six Sigma understands the external realities, the company strategy, and the annual business goals and financial targets. Every project should have line of sight from each project to the corporate strategy or to the annual operating plan. Goal trees to the strategic and or annual business plan are a great visual depiction of the system (see Figure 15.3). Several manufacturing plants in AlliedSignal displayed these goal trees in their cafeteria to better communicate their Six Sigma activities.

Figure 15.3 Example of projects linked to performance target and strategy.

This process step has a list of associated subprocess steps. They are

• Process Inputs: Strategic plan and AOP input from the business:

1. Clarify the “big picture.”

2. Establish and document performance baseline and entitlement.

3. Organize opportunities and prioritize.

4. Select key projects with leadership buy-in.

5. Check for accountability to business and personal performance objectives.

• Process Outputs: The output of the project selection step is a list of the top Six Sigma projects that will boost significant business productivity performance agreed on by the operations and business leadership and are linked to the strategy.

Objective of Step 1. The objective of selecting the right projects is to target the key business processes that are impeding significant productivity performance and are preventing the achievement of the company strategy. From his outstanding book, The Power of Alignment, George Labovitz (with Victor Rosansky) says that the greatest challenge that leaders have today is, “The main thing is to keep the main thing, the main thing!”

The diagram in Figure 15.4 shows the linkage between four components: our strategy, our customers, our people, and our processes. The processes link is what connects these linkages with Six Sigma. Our work is done through processes. If our processes are bad, our work is difficult and always lacking in some way. There are thousands of potential projects hiding within the processes in every business. The art of identifying the relatively few projects that will levy the most payback is the art of selecting projects.

Figure 15.4 Example of linkages made in a Six Sigma deployment. Six Sigma is about making those connections.

Step 1.1—Clarify the Big Picture. Clarifying the big picture is the process of establishing linkages. Going to the business model, we must link the issues associated with our external reality to clearly stated financial and operational targets and coordinated internal activities.

The two substeps for Step 1.1 are to identify the business strategic objectives and to translate these into primary operational objectives for all levels and divisions of your organization. Along with these objectives, financial and performance targets will be defined. So if productivity improvement, cash flow improvement, and cost improvement are the important things, these must be made crystal clear to the company.

Any projects that don’t address these three strategic areas are immediately called into question. Clarifying the big picture can be simple. Paul Norris, CEO of WR Grace, simply put one slide on the overhead projector: $56 Million. That’s the level of pretax profit he was looking for at the end of the year. Everyone in the room was aligned with Paul. The level of urgency noticeably increased. Figure 15.5 shows a summary diagram of Step 1 of the leadership roadmap.

Figure 15.5 Summary of Step 1 of the Six Sigma leadership roadmap.

Step 1.2—Establish Organizational Performance Baseline and Entitlement. The next step is to have the organizations deploying Six Sigma establish their performance baselines and performance entitlements (the best possible performance given the current process). This step might be aimed at manufacturing only or manufacturing and other specified parts of the company.

One step might include doing an analysis of cost-of-poor-quality and waste in important processes. Conduct a “hidden factory” analysis to define manufacturing entitlement by identifying a comprehensive list of areas of waste or cost-of-poor-quality in the manufacturing process (i.e., brainstorm the question: “what are the sources of waste or inefficiencies in our manufacturing process?”). You can also do similar analyses for any process area—even legal, for example. Where is our legal department suboptimal? What is the financial benefit of fixing those things?

Group these lists of waste and COPQ into the broad categories of rolled throughput yield, capacity, productivity, COPQ, or product quality. Brainstorm a list of potential projects to contribute breakthrough wins in the businesses target areas of improvement (i.e., focus on the areas with the strongest links to the business needs).

Step 1.3—Organize Opportunities and Prioritize. Assign $ value to each project in the potential project list from baseline analysis. Plant finance must be involved in this step. Value should be stated in terms of $ value to operating income.

Next, estimate timing to complete (short-, medium-, or long-term) the project. Traditionally, we’re looking for projects that take no more than six months to complete. We are ready to estimate resources needed to complete the projects (people, time, capital $, and expense $).

Finally, organize potential projects into a priority matrix (value, timing, and resources needed). Rank projects based on priority matrix output. Be sure to do a reality check on the top projects in the matrix.

Are these projects really doable? Is there a real link to the business (i.e., are the capacity improvement projects for products that are sold out?). Are the resource needs realistic? Then re-rank as needed. The output of this step is a list of the top recommended projects that will most significantly improve the results of the business. This process is described in detail in Chapter 9.

Step 1.4—Select the Key Projects with Leadership Buy-in. Review the recommended list of the top projects with the managers of Operations, Process Engineering, Sales and Marketing, Legal, HR, and so on. Within each function, agree on the top projects to target for this year.

Assign accountability to the owning manager. The owning manager reviews the projects with their business segment team to validate alignment with the needs, strategy, and financial targets of the business. Based on approval by the business segment team, the owning manager develops a project charter for each selected project with clearly defined objectives, timing, and linkage to the business. The output of this step is a complete project list, complete with project charters.

Step 1.5—Check for Accountability to the Business and Personal Performance Objectives. To ensure that the projects are linked to the future direction of the company, verify linkage for each project to the strategic plan. In addition, verify linkage/integration of each project with the AOP. Put them in the AOP if they are not already there.

Build the Six Sigma goal trees to demonstrate clear linkages. Include in the performance objectives of the owning manager on the proposed project list. The output of this step is clear business linkage and defined accountability.

Step 1 Outputs. The output of the project selection step is a list of the top Six Sigma projects that will yield significant business productivity performance agreed on by the business leadership. Figure 15.5 shows a summary diagram of Step 1 of the leadership roadmap with the five substeps.

Six Sigma Leadership Step 2—Select and Train the Right People

Objective of Step 2. Step 2 showcases the process of identifying and defining roles of the critical people needed for successful completion of the key targeted projects, which were output from Step 1. Chapters 8 and 11 address this step in detail.

Step 2 Process Input. The input of this process step is a list of the top Six Sigma projects leading significant business productivity performance as agreed on by the division and business leadership.

Step 2 Process Steps. Process Step 2 consists of five subprocess steps. This step addresses selecting, systematically training, and providing time and resources for the students to complete their Six Sigma project work.

1. Ensure the right leadership and ownership.

2. Develop a training plan for the right people.

3. Provide the right training.

4. Dedicate time for the trainees to complete projects.

5. Ensure the right resources are available.

Step 2.1—Ensure the Right Leadership and Ownership. The manager or leader that owns projects visibly champions key projects by face-to-face education of their organizations on the goal trees. Clearly defining the linkage of each project to the strategy of the annual operating plan, and to beating the financial targets, develops a sense of urgency within the Six Sigma project teams to complete the projects.

Use these meetings to establish the WIIFM (What’s in it for me?) for the owning organization for the key projects. The output of this step is clear communication of the business and manufacturing goal trees down to the key project level. The other output is to demonstrate that your leadership is counting the success of each project to reach its strategic vision.

Step 2.2—Develop a Training Plan for the Right People. The second step for Step 2 is to first identify potential Six Sigma candidates from across the company. You will be searching for candidates within the executive leadership, the Six Sigma Initiative Champion, Six Sigma Deployment Champions, Project Champions, Black Belts, Green Belts, and Yellow Belts. You will also be looking for candidates for Master Black Belts. This is a pretty complex group to train, and an annual plan is the key to making the training happen.

Now that you have a list of prioritized projects from Step 1, tentatively match these candidates to the Six Sigma project with the best fit. You may use the following suggested criteria to test the realistic fit of the candidate to the target project. The candidate:

1. Has an understanding of the targeted business process?

2. Has general technical acumen?

3. Has ability to work within and lead a team?

4. Has a bias for action?

5. Is willing to change the status quo?

6. Has a desire to work on the project?

7. Will be in his/her position long enough to finish the project?

8. Can be relieved of current duties for time needed for successful completion of the target project?

a. For Black Belts, this must be >75 percent (100 percent for top five projects).

b. For Green Belts, this must be 25 to 50 percent.

c. For Yellow Belts, this must be >25 percent.

The final task is to document the training plan for the identified Six Sigma training candidates. This plan should be reflected in each segment of the company’s annual operating plan. The output of this process step is a documented training plan identifying the Leaders, Black Belts, Green Belts, Yellow Belts, and Master Black Belts and their assigned projects.

Step 2.3—Provide the Right Training. A guiding coalition of Six Sigma function leaders and Six Sigma Champions will be responsible for executing the annual training plan. Course schedules and the training resources will be ready. Six Sigma training plans are extensive and include more training time than usual. For example, here are some estimates of Six Sigma training time for various programs:

1. Champion Training—three to four days

2. Executive Training—two to three days

3. Black Belt Training—four to five weeks

4. Green Belt Training—two weeks

5. Yellow Belt Training—four days

6. Master Black Belt Training—five to eight weeks

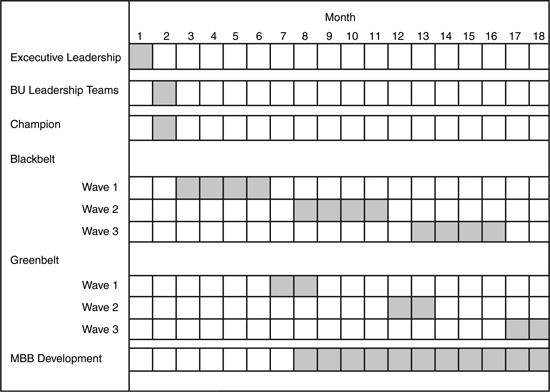

Figure 15.6 presents a straw man annual Six Sigma training plan. The word “wave” is synonymous with “class.” The plan should include a high-level schedule such as this, as well as an estimate of the number of people to be trained in each event. You should be able to track the number of people trained in Six Sigma over time.

Figure 15.6 Example of a straw man Six Sigma training plan over the course of one year. The term “wave” is synonymous with “class.” This plan is coordinated with project selection.

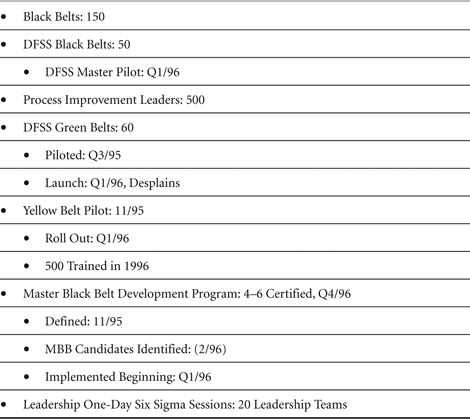

Table 15.1 demonstrates an actual two-year draft of a large company’s Six Sigma training plan. Notice the number of Green Belt events on the plan. Once Six Sigma is deployed, this company reinvigorated Six Sigma by launching new programs with different focuses and different goals.

Table 15.1 Example of a Two-Year Six Sigma Training Plan

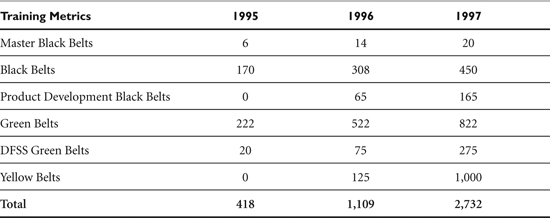

Table 15.2 shows an actual three-year summary of Six Sigma training from a $14 billion sector of a large Fortune 500 company. This chart shows the commitment of that sector’s leadership to ensure that Six Sigma became part of the company’s culture. This program resulted in millions of dollars in financial benefit.

Table 15.2 Example of a Three-Year Summary of Six Sigma Training Activities

Step 2.4—Dedicate Time for the Black Belts and Green Belts. A controversial issue that inevitably rears its ugly head during every Six Sigma deployment is the time the Belts should dedicate to their projects. This issue is covered in Chapter 13, “Creating the Human Resources Alignment.” The suggestions range from 100 percent of their time to some percentage of their time. Our data clearly shows that the more time the Belts spend on their projects, the faster the projects get completed. If you have identified a project worth a million dollars, why would you want someone to work part-time on it? I’ll present some recommendations.

For the top-five productivity projects in each functional area, I suggest you relieve Black Belts from their regular duties. Assign them to work 100 percent of their time for the 4–6 months they will spend on their key project. During this period, consider assigning them to report to the Six Sigma Project Champion (at least on a dotted-line relationship). Note: The people in this core project group should rotate out every year or so. Assign remaining Black Belts to work 75 to 100 percent of their time on their assigned projects.

Assign Green Belts to work >50 percent of their time on assigned projects. For each of the Black Belts and Green Belts, clearly define what work they will stop doing and who, if anyone, will pick it up so the needed time is really available.

The site Master Black Belt and finance person should provide continuous technical support to all Black Belts and Green Belts. Clearly set performance expectations for Black Belts and Green Belts by incorporating their project goals in their annual performance objectives. Make sure they understand and accept the changes needed in their work-style (shift from fire-fighting to continuous process improvement focus). Manage Black Belt and Green Belt performance actively. Assess regularly and support/discipline/coach as needed.

Step 2.5—Ensure the Right Resources Are Available. Just assigning a project to someone without dedicating the resources can be classified as cruel and unusual punishment. During the project selection process, leadership also is aware of required resources and commits the resources required for each project. Table 15.3 shows “mini-charters” for a small set of projects that indicates the leadership group was aware of who the resources were before the project was officially chartered. This table also shows cost estimates and capital estimates for each project along with an estimate of business benefits.

Table 15.3 Example of Actual “Mini-Charter” Detailing the Initial Requirement for Resource (Both People and Capital)

So, identify the people with the skills and knowledge needed to help solve the problem and select those who can dedicate the needed time to contribute.

Assemble Six Sigma teams around the specific projects. Each team should be led or championed by a Black Belt or a Green Belt.

Step 2 Output: The right project owners and leaders with a shared commitment.

Six Sigma Leadership Step 3—Develop and Implement Improvement Plans for Key Six Sigma Projects

This is the step in the leadership roadmap where the rubber meets the road. Six Sigma is based on process improvement roadmaps. There are different roadmaps for different functions. There is a specific roadmap for manufacturing operations. There is another roadmap for transactional functions such as HR, legal, and purchasing. R&D and product development have their own set of roadmaps. There is even a version of Six Sigma that integrates Lean manufacturing into the roadmap.

Objective of Step 3: To translate the acquired process improvement roadmaps and tools into progress for each of the key targeted projects.

Step 3 Process Input: The right project owners and leaders with a shared commitment.

I will describe the manufacturing operations roadmap to give you an idea of the structure of process improvement. This roadmap is based on the Measure, Analyze, Improve, and Control (MAIC) process. I’ve shortened the roadmap in lieu of time and space for this section.

Step 3.1—Measure the Targeted Process.

1. Define and document key product, customer requirements (Key Process Output Variables), program objective(s), performance variables, and process specifications resource requirements. This analysis should be based on the evaluation of rolled throughput yield (RTY), cost of poor quality (COPQ), and capacity-productivity (C-P).

2. Create a detailed process map and define Key Process Output Variables (KPOVs) and Key Process Input Variables (KPIVs) for each step of the process. Create a cause and effect (QFD) matrix relating Key Process Input Variables to Key Process Output Variables. Prioritize the KPIVs. Perform an initial assessment of the process control plan.

3. Identify gauge capability requirements for each key output and input variable and complete gauge studies as required.

4. Perform a short-term capability study on KPOVs to establish “first look” capability and establish process baseline.

Step 3.2—Analyze the Targeted Process.

1. Complete a Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) to determine input variables that have high risks.

2. Perform multi-vari studies to understand how Key Process Input Variables (KPIVs) vary in the factory and to get a first quantitative look at the relationship between KPIVs and KPOVs.

3. From the FMEA and multi-vari studies, prioritize a list of KPIVs to test impact on KPOVs.

4. Review program and develop roadmap for establishing characterization, optimization, and reliability. Focus on capability study results, FMEA, and other sources of engineering inputs.

5. Plan first steps for the Improvement step.

Step 3.3—Improve the Targeted Process.

1. Use design of experiments (DOEs) to characterize the influence of the KPIVs on the KPOVs and to define sensitivity of KPOVs to changes in KPIVs. Identify and verify critical KPIVs using sequential DOEs and Evolutionary Operations (EVOPs).

2. Use DOE methods to establish optimal operating windows for the KPIVs.

Step 3.4—Control the Targeted Process.

1. Develop, document, and implement process support systems (training modules, maintenance plans, troubleshooting guides, process procedures, etc.) for a long-term capability run.

2. Demonstrate validity of operating windows through a long-term capability study.

3. Conduct final review of the program, write final report, and update support system documentation.

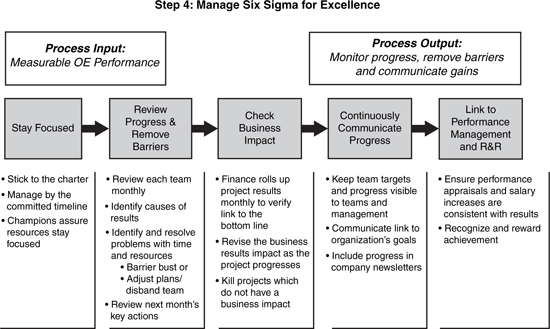

Six Sigma Leadership Step 4—Manage Six Sigma for Excellence

The objective of Step 4 in the Six Sigma leadership roadmap is to provide the necessary on-going leadership and management support and guidance to ensure optimum results of the Six Sigma process in your organization. This step consists of six process substeps. The lucky thing is these are the same steps for driving any initiative. The six substeps are as follows:

1. Stay focused.

2. Actively champion resources needed for progress.

3. Frequently review progress of projects.

4. Reality check the real business impact.

5. Continuously communicate progress.

6. Reward, recognize, and discipline performance.

Now, let’s review each of the six substeps. Figure 15.7 shows a graphic of Step 4.

Figure 15.7 Step 4 of the Six Sigma leadership roadmap with substeps.

Step 4.1—Stay Focused. Common to many initiatives that work, the ongoing support and pressure from the organizational leaders are necessary. Success in this step is the function of clear accountability for results at all levels of the organization. This accountability leads to distinct behavior changes.

Success is related to maintaining focus on the goals of the projects and the long-term direction of the initiative. Black Belts keep projects focused on the key success factors for the business. Regular reviews of breakthrough projects provide leadership to the Black Belts. Review of the project’s benefits and contribution to AOP and strategic plan goals is essential.

For example, the project-owning manager (Champions) will make sure their people are sticking to the project charter and progressing to the committed timeline. They will also actively manage Black Belt and Green Belt project focus and organizational leadership, and do a “direction check” quarterly.

Step 4.2—Actively Champion Resources Needed for Progress. The fastest way to undermine a Six Sigma deployment is to let people block the Six Sigma teams from getting the resources they need. That’s why it’s so important for the organizational leaders to do a frequent reality check on resources. Is this a barrier for progress?

It’s also essential to remove barriers to success and to barrier-bust where needed to get resources for key projects. If a team cannot get investment needed for progress, declare defeat and quickly move the Black Belt or Green Belt to another project. Note: This should not happen if good project selection was done.

Step 4.3—Frequently Review Progress of Projects. The easiest way to institutionalize Six Sigma is to review the program frequently at all levels. The plant manager may review his/her program once per month, the business president may review the program for his/her business once per quarter, and the CEO would review once per quarter as well.

For example, a manufacturing plant would plan to report monthly Six Sigma progress to their business leadership (in a flash report format). Black Belts hold monthly Six Sigma progress reviews with the group of project owners or Champions. The owning managers would schedule one-on-one reviews with Black Belts and Green Belts at key milestone dates to recognize progress, identify barriers, and reinforce expectations.

Champions summarize monthly the Six Sigma results of the key projects. The objective of these reviews is to sustain the drive for implementation and closure! Note: I suggest having the owning managers occasionally report on the progress of the projects they own instead of Black Belts.

Quarterly reviews of the entire Six Sigma system should be conducted at the business level. The focus is on the following:

• Project identification

• Project tracking

• Communications

• Accuracy of financial impact assessment

• Time commitment of Black Belts

• Project review processes

Findings from the review should be used to improve system weaknesses and promote strengths.

Step 4.4—Reality Check the “Real” Business Impact. To ensure that Six Sigma does not turn into a TQM program (lots of action and no results), it is crucial to have finance groups roll up project results monthly and verify link to “bottom-line” results (i.e., operating income). This action also gives the project champions an opportunity to revise the business results impact if needed as the project progresses. If necessary, the organization must learn that it’s okay to “kill” projects that are failing the business results criteria. This decision should be in the hands of the owning manager, finance, and the business leader.

Benefits from each project are tracked and validated by the financial community to determine the project impact to the bottom line. Finance is involved in project chartering as well as project reviews to ensure

• Financial goals are properly calculated.

• Financial results are bridged to the bottom line.

Business Managers are required to sign off on projects in support of their business impact. Therefore, Business Managers must be included in project reviews when financial and business impacts are being reviewed.

Step 4.5—Continuously Communicate Progress. As with any change program, communicating program success constantly is so important. This communication might be monthly for a function as they progress toward their goals on using two-way communication. Also important is linking to the organization’s performance in Six Sigma to various company award and recognition meetings. The Six Sigma communications plan is the foundation upon which the Step 5 activities are based. Constant communication is the hallmark for success.

Step 4.6—Reward, Recognize, and Discipline Performance. To anchor Six Sigma into your company, you must make it personal. Rewarding and recognizing fine performance is necessary, and driving discipline in performance is just as important. Ensure that Black Belt and Green Belt performance appraisal and salary increases are consistent with their annual performance objectives.

Reward and recognition programs must be appropriate for Black Belts/Green Belts and teams for significant results. Six Sigma teams will be performing at levels not previously seen in your company, which may prompt a revision of your current programs.

Everyone asks the question, “WIIFM?” Reward and recognition does not have to be monetary in nature, but reward systems should be consistent across the company, divisions, and plants. Rewards are correlated to the success of the project and the benefits to the business. Recognition should be public and formal at plant, division, and company levels. Ideas for rewards and recognition include the following:

• Team celebration day

• Gift certificates

• Trophies/plaques

• Company gifts

• Publication/invitation to present at company and corporate levels

Six Sigma Leadership Step 5—Sustain the Performance Gains

In any organization, the two most difficult things to accomplish are (1) implementing a new system and (2) getting rid of the old system. Your Six Sigma projects are focused on using fact-based roadmaps to reengineer a business process to enhance its performance.

Black Belts claim success when they can walk away from the process and the solutions continue to be effective. Your projects will result in developing a new system with which to perform better and perform consistently. Your organization has to protect the new system and prevent the organization from going back to the old system. There are four substeps to step 5:

1. Implement effective control plans.

2. Conduct regular training.

3. Review the Six Sigma system quarterly.

4. Continually identify key projects.

Step 5.1—Implement Effective Control Plans. Control plans are the instrument to prevent performance from slipping back to the old level. The new process must be thoroughly documented and all process participants trained on that documentation. This would include documenting control plans, and training both operators and supervisors on those control plans. The next step is to establish metrics and a tracking system to measure control plan effectiveness. Finally, the last step is establishing regular internal audits to assess the effectiveness of the control plan.

Step 5.2—Conduct Regular Training. Training at all levels is important in sustaining the gains. The types of training that occur frequently and systematically are as follows:

• Tools training

• Leadership training

• Team skills training

• Business training

This step entails the development of a rigorous training process. Training of new operators and re-emphasizing methods to existing operators sustains long-term performance. Process knowledge must be effectively transferred to operators who are empowered to take control of their process. Training of support personnel (maintenance technicians, QA/QC personnel, etc.) will also be developed and implemented for their specific support roles. The focus of the knowledge transfer changes to the key process requirements.

Step 5.3—Review Six Sigma System Quarterly. Creating a survey or formal assessment is the primary action in this step. One of the best examples was the Quality Systems Review (QSR) created by Motorola to assess the health of Six Sigma throughout the company. You will also need to audit project results.

So, you can use the Six Sigma process survey to identify any areas needing improvement. Once these areas have been identified, the next action is to implement needed changes and check for results.

Step 5.4—Continually Identify Key Projects. The foundation for identifying future projects is to maintain a common database to collect productivity or product quality improvement ideas. Rely on new ideas generated by the workforce. All your organizations must habitually maintain a running list of the top “next 10” key projects and assign Black Belts and Green Belts as they become available. This is sometimes referred to as the “project hopper.” An easy question to ask a Champion is, “What are your next 10 projects?”

This last step of the leadership roadmap is important for truly anchoring Six Sigma into the culture. This is where the discipline of Six Sigma starts to happen consistently. To create a process change, the goal is to implement it quickly and have it last for years.

Six Sigma Handbooks and Other Anchors

During the front end of a Six Sigma deployment, have the Six Sigma Steering Team design a Six Sigma Handbook to document the way the initiative will be managed. The handbook is a great tool to use for company-wide training and for bringing new employees on board quickly. The following is a sample outline of a Six Sigma handbook.

Six Sigma Handbook

I. Cover Letter—Company CEO

II. Six Sigma Overview

III. Mission and Goals

a. Metrics/ Entitlement

1. Definitions and Calculations

b. Key Reporting Mechanisms

IV. Strategy

a. Strap/AOP

b. Six Sigma Planning

V. Roles and Responsibilities

a. Division Champion

b. SBU Champion

c. Site Champion

d. Master Black Belt

e. Process Improvement

1. Black Belts

2. Green Belts

3. Yellow Belts

VI. Six Sigma Projects

a. Method of Selection, Prioritization, and Assignment

b. Chartering

c. Tracking and Review System/Procedures

d. Process for Closing Out Projects and Key Deliverables

e. System for Archiving Projects

VII. Six Sigma Training

a. Structure/Format

1. Calendar

c. Black Belt

d. Green Belt

e. Yellow Belt

f. Analytical/Lab Green Belt

g. Master Black Belt

h. Business Leadership

VIII. Certification Requirements

a. Black Belt, Green Belt, Master Black Belt, Champion

1. Results

2. Deliverables

3. Approval

IX. Six Sigma Tools and Deliverables

a. Roadmaps, Methodology, and Tools

b. Supporting Tools

X. Process Control System

a. Process Map

b. Correlation Matrix

c. Control Plan

d. FMEA

XI. Infrastructure Support/Data Systems

a. Minitab

b. Downtime Tracking

c. Project Tracking

d. Microsoft Project

e. KPV Control System

XII. Six Sigma Plant Diagnostic

a. Objective

b. Description

c. Process

Six Sigma Assessment. Another Six Sigma anchor is a Six Sigma assessment or diagnostic. Motorola created the Quality Systems Review to assess Six Sigma throughout the company. This was a company-wide and centrally controlled process that kept the focus on Six Sigma. The Six Sigma assessment can be a simple questionnaire or a more complex process that includes numerous site visits. An example of a survey questionnaire item follows. The example includes the survey item, which is scored on a 1 (Poor) to 4 (Excellent) scale; each item would have four descriptors, one for each number 1 through 4.

1. We select the right problems to work on:

1.1 We randomly determine projects.

1.2 We use baseline data to select projects.

1.3 We use baseline data, and select projects by priority.

1.4 We use baseline data, select by priority, and link projects to strategic plan.

This particular set of examples follows the Six Sigma leadership roadmap we have been discussing. By surveying your people and summarizing the scores, you will quickly discern where you are strong and where you are weak. Examples of Six Sigma survey items are as follows:

1. We select the right problems to work on.

2. We select the right people to be BBs/GBs.

3. We manage for the right performance.

4. Our Six Sigma goals are defined and understood by all employees.

5. The role of the Black Belts and Green Belts are well defined and understood by the organization.

6. Our overall Six Sigma process is effective.

7. We identify primary business objectives as the basis for Six Sigma projects.

8. We use COPQ, RTY, and CP to identify new projects.

9. Our Six Sigma projects are of a manageable size.

10. We organize project prioritization information into a priority matrix (value, timing, resources needed).

11. Projects are doable and linked to business needs (a reality analysis).

12. Projects are linked to the strategic plan, included in AOP and clearly defined on goal trees.

13. We use defined criteria for BB/GB selection and project assignment. BB/GB understands the plant process, technically strong, able to work within and lead a team process, have a bias for action, and are willing to change the status quo.

14. Our BBs/GBs have the right level of experience to be successful and to establish credibility with operators and supervisors.

15. Which statement best describes how the owning manager supports BB/GBs?

16. We identify the people with knowledge of the problem and the skills to solve the problem and give them dedicated time to work on the problem.

17. We stick to the project charter and manage by the committed timeline.

18. We frequently do a reality check on resourcing ($ and people).

19. We frequently review progress of projects.

20. We implement and close projects.

21. Finance audits projects and verifies project results. Projects that fail the business results test are stopped. The bottom-line analysis is used to track monthly progress.

22. BB/GB performance appraisals are based on their Six Sigma progress.

23. BBs/GBs receive appropriate R&R for significant results.

24. Projects have effective control plans that are documented, implemented, and periodically audited to ensure that we sustain the desired results.

25. BBs/GBs receive appropriate leadership training.

26. Our Six Sigma efforts are providing the expected $ benefit.

27. Plant management reviews the prioritized project list and results of the “reality” analysis.

28. The Business Area manager shares projects with business (segment, marketing, etc.) leaders to validate alignment with business objectives.

29. Projects have the right leadership and ownership.

More complex and yet complete assessments are available. For example, the Motorola QSR has 11 subsystems and generates scores for each and profiles for each subsystem. It takes one week to complete and provides business-wide information. So, by following the Six Sigma leadership roadmap as described in this chapter, you will be well underway to making Six Sigma one of the best initiative deployments your company has ever seen.