China’s sovereignty claims over the Nansha Islands: a legal perspective

Abstract:

This chapter analyses several methods under international law that are applied by China to support and consolidate its claims over the sovereignty of the Nansha Islands. China was the first country to discover the Nansha Islands back in the Han dynasty, and has exercised successive administration over these features ever since. In addition, it has passed many laws and regulations to protect its sovereignty. China’s sovereignty claim is confirmed by international documents, including the Cairo Declaration, the Potsdam Declaration and the Treaty of Peace with Japan. It is also extensively confirmed by the relevant countries and international media. UNCLOS, with its newly established regime of ‘exclusive economic zone’ and ‘continental shelf’, creates competing claims between China and other states, which indicates a need for balance between historic and contemporary claims.

There are several methods that either are currently used or were historically recognised under international law as lawful means by which a state acquires territorial sovereignty: accretion, cession, conquest, occupation or prescription. This chapter explores China’s claims over the sovereignty of the Nansha Islands from a legal perspective.

Discovery in international law

Before the eighteenth century the principle of res nullius naturaliter fit primi occupantis was a basic rule for a country to obtain sovereignty for terra nullius. According to Jennings, discovery without occupation could be granted title in the past (Jennings and Watts, 1992: 687; Jennings, 1961: 21–3). After the eighteenth century international law requires actual occupation after discovery for sovereignty to be granted. According to post-eighteenth-century law, occupation requires that the subject of the occupation must be a country; the object must be terra nullius, referring to territory which has never been subject to the sovereignty of any state, or over which any prior sovereign has expressly or implicitly relinquished sovereignty; there must be a subjective intention of occupation; and objectively there exists the fact of effective possession, although discovery is still the basis for claiming title to a territory.

In view of the changing connotation of the principle of primo occupandis at different times, discussion of sovereignty for the geographic features in the SCS requires defining the period in which the principle of primo occupandis is applied, as this involves inter-temporal law.

Inter-temporal law determines whether to apply old or new laws as a result of changes to the law over time.1 In the dispute over the island of Palmas between the United States and the Netherlands in 1928, Judge Max Huber introduced the concept of inter-temporal law into international law for the first time (Reports of International Arbitral Awards, 1928). He elaborated the principle by which laws may be divided into three periods: the law when the legal facts came into being, the law when the dispute came into being and the law when the dispute was submitted for arbitration. Judge Huber pointed out that the legal facts should be judged based on the laws that existed during the same period, but not on the laws at the time when the dispute occurred or when it was referred to for legal settlement. If laws of different periods are involved in a specific case, when determining the applicability of law there must be differentiation between the point in time of generation of the title and the time period of existence of the title (ibid.). Activities that generate the title must be subject to the laws prevailing at the time when the title was generated. The annual meeting of the Institute of International Law held in Wiesbaden, Germany, in 1975 endorsed this principle in its resolution. Thus when judging the attribution of sovereignty for the disputed features in the SCS, the laws to be applied are those which existed when sovereignty for the features was generated, not the laws at the time the dispute occurred or was referred for legal settlement.

As described in Chapter 2, the Chinese discovered the SCS features no later than the Han dynasty, 1,500 years before the time (1630–1653 AD) when the Vietnamese claim to have carried out activities in the SCS. Even if the date of discovery of the Nansha Islands were moved to the eleventh to fourteenth centuries, when China’s navy and commercial fleet were at their strongest (Pan, 1986: 258), it was still 400 years earlier than Vietnam’s claimed date. During that period China led the world in ship-building technology and marine navigation techniques, such as use of the compass.

Starting with Hugo Grotius, a tradition has been established in international law that it should draw inspiration from Roman law and private law developed subsequently. ‘The result is, the regime regarding territory, the nature of territory, the scope of territory, and the acquirement and defense of territory in the international regime are all pure Roman “property law”’ (Maine, [1959] 2002: 58). Thus res nullius naturaliter fit primi occupantis has become the basic principle for a country to acquire terra nullius. Under Roman law, actual occupation is not necessary, as the discovery of res nullius itself generates ownership (du Plessis, 1992: 200). This was the principle that international law espoused in the early days. Thus, according to Jennings (1961: 43), ‘Discovery without occupation generates title in the past… Before the 16th century, there was no argument that mere discovery is adequate to generate title.’ The practices of colonial countries in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries prove this point. Zhao (1993: 171), who quoted from Hill, also pointed out that ‘since mere discovery is regarded as a sound base for claiming terra nullius, the practice of symbolic activities which might be considered as actual occupation or possession has been developing’.

After the eighteenth century international law requires actual occupation on top of discovery to claim sovereignty, but discovery is still the basis for claiming title. In the case of the island of Palmas arbitration it was regarded as a ‘preliminary right’ (Henkin, 1980: 251). According to Hall’s (1924: 127) extensively cited saying, discovery has the effect of temporarily preventing occupation. Oppenheim (1981: 77–8) also discussed this topic in detail; according to him, discovery is never of no importance.

Successive administration (prescription)

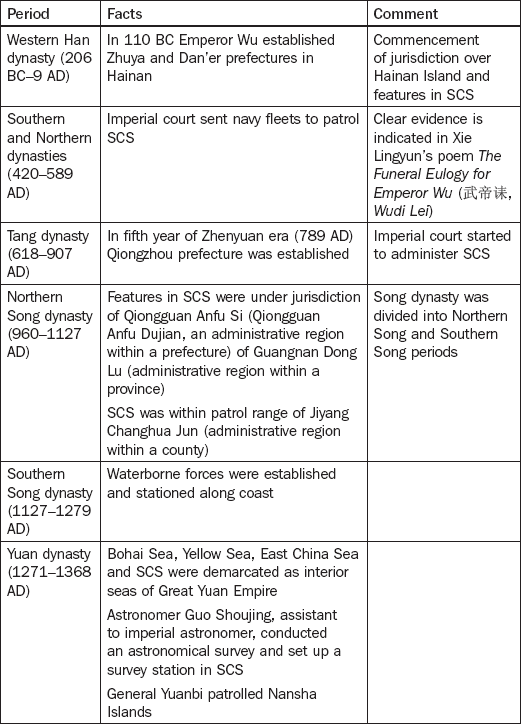

Prescription is related to occupation, and refers to the acquisition of sovereignty by actually exercising it for a reasonable period of time and without objection from other states. China’s exercise of sovereignty over the features in the SCS can be traced back to the Han dynasty. Table 3.1 illustrates the facts of China’s exercising successive administration over these islands.

Maritime legislation

Apart from administrative jurisdiction, China has passed many laws and regulations to protect its sovereignty over the features in the SCS. Although the Chinese have been conducting activities in the SCS since the very early days and each dynasty set up administrative agencies to take charge of SCS affairs, development of maritime legislation in China was delayed for several reasons: cultural differences between the East and the West; the unique status of China in East Asia or even the entire Asia; a strict policy banning maritime trade during the Ming and Qing dynasties; and weak maritime awareness in the feudal dynasties. In modern times the corrupt Qing dynasty continued to neglect China’s sovereignty and maritime rights over the features in the SCS. It was only at the end of the Qing dynasty and the beginning of the ROC that the Chinese government looked upon these matters as important and took a series of measures to protect China’s sovereignty over the SCS features. For instance, in 1931 the government issued a maritime policy and declared three nautical miles of ‘territorial sea’ and 12 nm of special anti-smuggling zone; however, no formal legislation was enacted.

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) the government took steps to protect China’s sovereignty and sovereign right over the features in the SCS and surrounding sea areas, and keep up with the development of international law of the sea. Laws concerning territorial sea, contiguous zone, exclusive economic zone and continental shelf were enacted. Legislation has become increasingly comprehensive, and thus a powerful means to protect and enforce China’s sovereignty in the SCS.

The Chinese government issued the Declaration on the Territorial Sea in September 1958, stating that the sovereignty of the Dongsha, Xisha, Zhongsha and Nansha Islands belongs to China, the straight baselines are the baselines of territorial sea and the extent of the PRC’s territorial waters measures 12 nm from the baselines of the territorial seas.

In February 1992 China’s government passed the Law on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone. Article 2 clearly states that sovereignty of the SCS islands belongs to China. The law also provides that the extent of both territorial sea and the contiguous zone of the islands in the SCS is 12 nm, and sets forth China’s rights within these areas.

In May 1996 the Chinese government ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, and stated that it was ready to resolve maritime disputes in a just and fair manner according to the convention. The government passed four declarations, one of which was to reaffirm Article 2 of the Law on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone so as to restate China’s sovereignty over the Dongsha, Xisha, Zhongsha and Nansha Islands. It also issued the Declaration on Baselines of Territorial Sea, stating the baselines of territorial sea of the Xisha Islands, and that the Chinese government will declare the remaining baselines of its territorial sea in the future.

In June 1998 the government passed the Law on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf to exercise sovereign rights in its EEZ and continental shelf. Article 14 provides that the provisions under the law do not affect China’s historic rights.

Several observations may be concluded from the above analysis.

First, it was the Chinese who first discovered the features in the SCS, and the Chinese government has been administering them since ancient times. Although maritime legislation was delayed for various reasons, the first maritime policy issued in 1931 laid a basic foundation for China’s maritime legislation and protects its sovereignty over the SCS features and sovereign rights in the surrounding sea areas.

Second, in the 1990s maritime legislation, including the Law on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone, the ratification of UNCLOS and the four statements, the publicising of the baselines of the territorial sea of the Xisha Islands and the enactment of the Law on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf, asserted China’s sovereignty over the features in the SCS and sovereign rights over their surrounding sea areas. After nearly 2,000 years of actual jurisdiction, it was the first time that China reiterated these sovereign rights through legislative means.

Third, maritime legislation is the legal basis on which the Chinese government relies to protect its sovereignty over the features in the SCS. Such legislation provides a domestic legal basis for the Chinese government to negotiate with disputant countries when SCS disputes arise, and for joint development in the SCS.

International acknowledgement and recognition of China’s sovereignty

China’s sovereignty over the Nansha Islands is confirmed by international conventions, including the Cairo Declaration, the Potsdam Declaration, the Treaty of Peace with Japan and the Sino-Japanese Treaty.

On 1 December 1943 the Cairo Declaration made by China, the United States and Britain declared that one of the objectives of the Second World War was to return to China territories such as Manchuria, Taiwan and Pescadores that Japan had seized (International Treaty Collection, 1961: 407). Soviet Union leader Joseph Stalin agreed completely with the Cairo Declaration and its entire content, stating that it was right to return Dongbei (Manchuria), Taiwan (Formosa) and Penghu (Pescadores) to China (Wu, 1999: 35). On 26 July 1945 the Potsdam Declaration signed by China, the United States and Britain set forth that the terms of the Cairo Declaration shall be carried out (International Treaty Collection, 1959: 77).

When Japan occupied the Nansha Islands (1939–1945), it renamed the Nansha and Xisha groups and other islands in the SCS as Xinnan Qundao and placed them under the jurisdiction of Kaohsiung county of Taiwan, which was ceded to Japan after the Sino-Japanese War of 18941895. The Cairo Declaration and Potsdam Declaration provided that Japan must return to China territories such as Taiwan and Penghu which it had taken. It was obvious that these territories include the Nansha and Xisha Islands. After the Second World War the Chinese government took over the SCS features, and undertook a series of legal processes between September 1946 and March 1947 to assert sovereignty based on the provisions of the Cairo Declaration and Potsdam Declaration. Thus China had completed the procedures of restoring its sovereignty of the Nansha Islands according to the Cairo Declaration and Potsdam Declaration before the signing of the Treaty of Peace with Japan.

Zhou Enlai, then foreign minister of the PRC, issued a statement on 15 August 1952 on the draft Treaty of Peace with Japan prepared by the United States and Britain. The statement pointed out that although the draft treaty provided that Japan should give up all titles over the Nansha and Xisha Islands, its failure to indicate that China was the recipient was an encroachment upon China’s sovereignty. In fact, the Dongsha, Zhongsha and Nansha Islands have long been China’s territory, and its sovereignty over the Xisha, Zhongsha and Nansha islands will not be affected with or without any provision, no matter how provisions are crafted (Wu, 1999: 36).

After the Treaty of Peace with Japan, Japan and the Taiwan authorities signed the Sino-Japanese Treaty in 1952. Under this, ‘Japan has renounced all right, title, and claim to Taiwan (Formosa) and Penghu (the Pescadores) as well as the Spratly Islands and the Paracel Islands.’ The treaty provided supplementation and analysis to what was unclear in the text of the Treaty of Peace with Japan, which was directed towards Japan. As the main party of the Treaty of Peace with Japan, Japan confirmed in the Sino-Japanese Treaty that the sovereignty of the ‘Spratly Islands’ belongs to China (ibid.: 38).

China’s sovereignty over the Nansha Islands is extensively confirmed by relevant countries and the international media.

Japan

The Japanese position that the Nansha Islands belong to China is seen in not only the treaties but also officially published maps, newspapers, periodicals and other public media.

The Standard World Maps recommended by Katsuo Okazaki, then foreign minister of Japan, and published by National Education Books Publishing House in 1952 confirmed that the Nansha Islands belong to China. The Yearbook of China edited by Japan’s China Research Center (1955: 3) mentioned James Shoal in its discussion about the area of China. The Yearbook of New China produced by Japan’s China Research Center in 1966 recognised that China’s coastline is about 11,000 kilometres long, running from Liaodong Peninsula to the Nansha Islands. The total length of coastline is 20,000 kilometres including the islands along the coast (Japan’s China Research Center, 1966: 114).

When Sino-Japanese relations were normalised in 1972, the Japanese government declared that it would observe Article 8 of the Potsdam Declaration upon returning to China the territory it once occupied. This is once again confirmation by the Japanese government that the Nansha Islands belong to China.

The Modern Encyclopedia (Japan Study Research Institute, 1973: 388) stated that ‘The broad territory of the People’s Republic of China starts from the coast of Heilongjiang River which is at about 53° of north latitude in the north, and to the Spratly Islands which is at about the equator. The length is about 5500 kilometers.’

On 19 January 1974 Asahi Shimbun commented that ‘The Spratly Islands is considered as “China’s territory” for centuries, and the maps published by countries in the world also marked it in China’s territory’ (Wu, 1999: 40). On 20 January 1974 Sankei Shimbun published an article saying:

From the historical point of view, China’s claim to the Spratly Islands and the Paracel Islands can be traced back to the Han Dynasty and earlier. In the fifteenth century, travellers from China had already arrived at those islands. The maps published in the Qing Dynasty show that those islands had already been marked as the territory of the Qing Dynasty. Thus, the main stream of observers’ opinions is that China’s claim is right. (Ibid.: 38)

On 20 January 1974 Yomiuri Shimbun recognised that Chinese fishermen had been living on the Nansha Islands since 1860. This is documented in historical facts. On 2 February 1974 Shukan Daiyamondo published an article entitled ‘A blitz on the coral reefs in the South China Sea’:

In the South China Sea are located the Pratas Islands, Paracel Islands, Macclesfield Bank, and Spratly Islands from north to south, and there was almost no one living on those islands. Although Chinese fishermen visited there seasonally, they had not settled down… But from the historical point of view, it was a fact that China possessed these islands in past centuries. France made Indochina its colony, and occupied the Spratly Islands. Japan, which opposed the French occupation, put the islands under the jurisdiction of Taiwan. After being defeated in the Second World War, Japan gave up these islands according to the Treaty of Peace with Japan, which was signed in San Francisco in 1952, and China claimed sovereignty over the Pratas Islands, Paracel Islands, Macclesfield Bank, and Spratly Islands immediately. (Ibid.)

Apart from Japan, parties to the Treaty of Peace with Japan, especially countries that were involved in the Nansha disputes such as France, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia, and powerful countries in Europe and America also recognised that the Nansha Islands are part of Chinese territory.

France

‘Recognition’ by France may be found in two types of records. One type concerns facts before France invaded the nine islands in the Nansha group during the 1930s. According to these records, the French did recognise that Chinese fishermen were already fishing in the Nansha Islands before the French set foot on the islands. Another type of record is maps formally published in France.

Under the first type of records is a frequently cited article entitled ‘New islands of France’, written by a French author and first published in L’illustration. It was subsequently translated into English and published in the South China Morning Post (1933).

The Map of Southeast Asia, No. 13B in the Atlas International Larousse Politique et Economique, shows ‘the Pratas Islands (China)’, ‘the Paracel Islands (China)’ and ‘the Spratly Islands (China)’ (Wu, 1999: 37). These illustrations prove that these islands are the sovereign territory of China. The General Map of the World published by the Institut Geographique National Frangais (1968) and the Atlas Larousse Modern published in Paris (Curran and Coquery, 1969) also marked the Nansha Islands as part of Chinese territory.

Vietnam

Vietnam’s recognition of China’s sovereignty over the Nansha Islands is extensively seen in its official documents, such as government declarations and notes, and also in its newspapers, periodicals, maps and textbooks.

In early June 1956 the Ngo Dinh Diem authority issued a series of declarations claiming ‘traditional sovereignty’ over the ‘Paracel Archipelago and the Spratly Archipelago’. When Ung Van Khiem, vice foreign minister of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, met Li Zhimin, chargé d’affaires of the Chinese embassy to Vietnam, on 15 June 1956, Ung remarked that ‘According to the information Vietnam has, the Paracel Archipelago and the Spratly Archipelago should be China’s territory from [the] history point of view’ (Wu, 1999: 39). Le Loc, executive director of the Department of Asian Affairs, who participated in the meeting, provided additional official information and pointed out that ‘From a historical point of view, the Paracel Archipelago and the Spratly Archipelago were already China’s territory early in the Song Dynasty’ (ibid.: 38). Ung further said that the government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam ‘is going to publicise information that Vietnam’s government has collected… newspapers and periodicals so as to coordinate with China’s struggle’ (ibid.: 39).

On 4 September 1958, based on the 1958 Declaration on China’s Territorial Sea, the Chinese government declared that the extent of China’s territorial sea was 12 nautical miles. The first and the fourth provisions of the declaration stated that the 12 nm territorial sea and the straight baseline method ‘apply to all territories of the People’s Republic of China, including. the Dongsha Islands, Xisha Islands, Zhongsha Islands, Nansha Islands, and other islands belonging to China’. On 14 September 1958 Pham Van Dong, prime minister of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, sent a note to Premier Zhou Enlai, stating that ‘The Socialist Republic of Vietnam recognises and agrees to the People’s Republic of China’s declaration on 4th September 1958 regarding its territorial sea. The government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam respects this decision’ (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1980).

Before 1975 the Nansha Islands were marked as territory of China in all official maps, books and periodicals of Vietnam. The World Map drawn and published by the General Staff Headquarters of Vietnam People’s Army in 1960 marked the Xisha and Nansha Islands in Chinese names and noted that they belong to China: ‘Xisha Qundao (China)’ and ‘Nansha Qundao (China)’ (Wu, 2009: 48). In the Atlas of Vietnam (National Bureau of Surveying and Mapping of Vietnam, 1964), Chinese phonetics were used to spell out the names of the various islands: ‘Quan dao Dong-sa’ (Donghsa Islands), ‘Quan dao Tay-sa’ (Xisha Islands) and ‘Quan dao Nam-sa’ (Nansha Islands). In addition, the Xisha and Nansha Islands are marked in the same colour as Chinese territory, different from the colour of Vietnamese territory. Similarly, the Atlas of the World (National Bureau of Surveying and Mapping of Vietnam, 1972: 19) used Chinese phonetics to spell the names of the Xisha and Nansha Islands (Quan dao Tay-sa and Quan dao Nam-sa, respectively), to show that the two archipelagos belong to China. These archipelagos had never been marked ‘Quan dao Hoang Sa’ and ‘Quan dao Truang Sa’, the names currently used by the Vietnam authorities (Han et al., 1988: 634).

In the chapter on ‘China’ in a geography textbook published by the Education Publishing House of Vietnam in 1974, the Nansha Islands are also recognised as belonging to China. The textbook says, ‘The arch shape island chain which is formed by the Spratly Archipelago, the Paracel Archipelago, Hainan Island, Taiwan Island, the Pescadores, and the Zhoushan Archipelago has constructed a “Great Wall” to defend the mainland of China’ (Education Publishing House of Vietnam, 1974).

In fact, even Vietnamese maps of Vietnam did not include the Nansha Islands as part of the country’s territory. For instance, on the Administrative Map of Vietnam published by Vietnam in 1958 the Nansha Islands are marked outside Vietnamese territory (Education Publishing House of Vietnam, 1958); likewise for the Atlas of Vietnam (National Bureau of Surveying and Mapping of Vietnam, 1964), the Map of the Topography and Roads of Vietnam (National Bureau of Geography, 1966) and the Administrative Map of Vietnam (Education Publishing House of Vietnam, 1968). The Natural Geography of Vietnam (Education Publishing House of Vietnam, 1970) and the Regions of the Natural Geography of Vietnam (Science and Technology Publishing House of Vietnam, 1970) clearly pointed out that the easternmost territory of Vietnam is located at longitude 109°21’ east.

In fact, the Geography of Vietnam indicated that the country of Vietnam lies between ‘latitude 8°35’ and 23°24’ North, and longitude 102°8’ and 109°30’ East’. The Wan’an Tan (Vanguard Bank), southwest point of the Nansha group, is at 109°55’; thus to say the Nansha Islands are the territory of Vietnam is untenable (Le, 1957: 124–8).

The Philippines

In May 1956 Carlos P. Garcia, then secretary of foreign affairs of the Philippines, claimed at a press conference that some islands in the SCS, including Itu Aba and the Nansha group, should belong to the Philippines (Wu, 2009: 48). He received immediate protests from the PRC Foreign Ministry and the Taiwan authorities. On 7 July 1956 Manila Daily published an article recognising that the Nansha Islands belong to China (ibid.). After the Cloma claim (see Chapter 5), there is little material in the Philippines indicating its stance that the Nansha Islands belong to China; nonetheless, the Philippines has stated several times that it had no sovereignty over the Nansha Islands (Research and Planning Committee, 1995).

Indonesia

In early 1974 the South Vietnam authorities launched an armed attack on the Xisha Islands; this behaviour was condemned by the international community. Adam Malik, then foreign minister of Indonesia, told reporters: ‘If we have a look at the maps published today, we can see that both the Paracel Archipelago and the Spratly Archipelago belong to China, and that no one had ever made any protest’ (quoted in Wu, 2009: 56). On 6 February 1974 the Everyday News of Bangkok published a short article entitled ‘The view of Indonesia’ (ibid.: 48), saying that the foreign minister of Indonesia had driven the point home to Vietnam, for Vietnam had claimed that the ‘Paracel Archipelago’ and ‘Spratly Archipelago’ were its territory. Currently at least Indonesia, one of the largest countries in Southeast Asia, is openly opposing Vietnam’s claim (Xinhua News Agency, 1974a).

Malaysia

Before the 1970s Malaysia had never laid claim to the Nansha Islands, and its government had never reacted formally to any matter that occurred on the SCS. The Malaysian press also regarded the Xisha and Nansha Islands as China’s territory. On 21 January 1974 Penang’s Kwong Wah Yit Poh published an editorial entitled ‘The conflict between China and Vietnam on the Paracel Archipelago’:

Either from a historical or from [a] geographical point of view, the four archipelagoes in the SCS are part of China’s territory. This is undeniable and unarguable. The Chinese government had been taking a more relaxed policy towards the islands for a few reasons: First, China was caught in civil war and was suffering from foreign invasion; second, it did not have a strong navy force; third, the features have little economic value, and China did not have the economic power to administer them. Nevertheless, official documents and maps have shown that these islands have always been the territory of China. (Quoted in Wu, 1999: 41; Can Kao Xiao Xi, 1974a)

On 28 January 1974 Penang’s Guang Ming Daily published an article entitled ‘China’s “islands in the South China Sea”‘. It says:

The Nansha Islands and three other archipelagoes (the Dongsha Islands, Zhongsha Islands, and Xisha Islands) have been China’s territory for a long time. Fishermen from Hainan Island have been fishing there since several hundred years ago. Some of the fishermen even lived on the islands. In 1883 (the ninth year of Emperor of Guangxu of the Qing Dynasty), the German government sent people to survey the Nansha Islands. They had to withdraw because of protest by the Chinese government… During the Second World War, the islands in the South China Sea were occupied by the Japanese. After the Japanese surrendered in 1945, when the Chinese government regained the islands, it set up monuments on the islands. The Chinese government had declared in 1951 that the sovereignty of the Nansha and Xisha islands is inviolable. (Quoted in Can Kao Xiao Xi, 1974c)

Again, on 5 February 1974 the Guang Ming Daily wrote an editorial titled ‘Vietnam creates dispute’, saying:

There is abundant historical and geographical evidence to prove that the Xisha Islands, Dongsha Islands, Zhongsha Islands, and Nansha Islands are the territory of China; however, China was very weak over the past several hundred years and was invaded by western powers. Even China’s territory in the mainland was at risk of being divided up by western powers. As a result, it had no power to administrate the islands. After the Second World War, the Chinese government sent navy troops to take over the Xisha Islands. Both the French and the Vietnamese authorities did not object. This means that they had acquiesced to the status quo. Vietnam did not claim sovereignty until the San Francisco peace conference. That was the time when Vietnam attempted to encroach on the islands in the South China Sea. From a legal perspective, the Chinese government has never recognised the peace treaty. From [a] theoretical perspective, Vietnam’s position has been inconsistent and is unacceptable. (Quoted in Xinhua News Agency, 1974b)

The United States

As a signatory to the Cairo Declaration and Potsdam Declaration, the United States agreed that Japan must return the territory it had seized from China. In addition, books, periodicals and maps published in the United States recognise that the Nansha Islands are part of Chinese territory. The Columbia Lippincott Gazetteer of the World states that ‘The Spratly Archipelago, the Spratly Island of China, is the territory of China, is part of Guangdong Province’ (Seltzer, 1962).

The Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations described China as including the Nansha Islands: ‘The territory also includes some islands, for instance, the reefs and islands locate at 4° of the north latitude in the South China Sea. These islands and banks include the Pratas Archipelago, the Paracel Archipelago, the Macclesfield Bank, and the Spratly Archipelago’ (Worldmark Press, 1963: 55).

In the entry ‘People’s Republic of China’ in the Encyclopedia of World Administrative Division published in 1971:

The People’s Republic of China includes several archipelagoes. Among them, the largest is the Hainan Island located on its southern coast. Other archipelagoes include some rocks and archipelagoes in the South China Sea. The southernmost is at latitude 4° North. These rocks and archipelagoes include the Dongsha Islands, Xisha Islands, Zhongsha Islands, and Nansha Islands. (Wu, 1999: 43)

The entry for ‘Spratly Archipelago’ in Webster’s New Geographical Dictionary (Merriam-Webster, 1972) states: ‘Those small archipelagoes in the center of the South China Sea. were seized by Japan as the base of its submarines in June 1940. In 1951, Japan gave up the title on these islands.’

On 19 February 1974, in an article entitled ‘China’s Paracels are violated’, Can Kao Xiao Xi (1974b) wrote:

To most of the public opinion in the international law circle, Saigon’s claim to the Paracel Archipelago and the Spratly Archipelago is lame. The mapping of these maps was based on these public opinions. In standard reference books and atlas, including the United States, these two archipelagoes are China’s territory… The Paracel Archipelago, the Spratly Archipelago, the Macclesfield Bank, and the Pratas Archipelago have always been part of China’s territory. China’s sovereignty over these islands is popularly recognized in international reference books.

In 1974 US Senator Mike Mansfield, when suggesting that the PRC be given ‘most favoured nation’ treatment, commented that China’s claims to the ‘Spratly Archipelago’ and ‘Paracel Archipelago’ ‘are justifiable’ (quoted in Wu, 2009: 59).

Other countries and international organisations

In 1971 a British senior diplomat to Singapore acknowledged that the Nansha Islands were Chinese territory. He remarked, ‘The Spratly Archipelago is the territory of China, part of the Guangdong Province. [and] was returned to China after the Second World War. We cannot find any sign that it had ever been possessed by any other country. Thus, it can only be concluded that it is still possessed by Communist China’ (quoted in Wu, 2009: 59).

On 16 June 1976 a Times editorial titled ‘Contesting the Spratly Archipelago’ pointed out that Beijing ‘uncompromisingly restated that China has sovereignty over the Spratly Archipelago.’ (quoted in Wu, 1999: 43).

In February 1955, at the first conference of the World Meteorological Organization’s Regional Association for Asia in New Delhi, India, delegates from Hong Kong suggested the Taiwan authorities of China should reconstruct meteorology facilities on the Dongsha, Xisha and Nansha Islands to conduct aerological observation so as to meet the needs of international shipping. On 27 October 1955, Resolution No. 24 adopted by the International Civil Aviation Organization conference on Pacific regional aviation held in Manila requested the Taiwan authorities of China to improve meteorological observation on the Nansha Islands (Research and Planning Committee, 1995a). Apart from Taiwanese delegates, there were delegates from Australia, Canada, Chile, Dominica, South Korea, Laos, the Netherlands, Thailand, Britain, New Zealand, France, Vietnam, the United States, the Philippines and Japan. The results of Resolution No. 24 demonstrate that all participating countries and regions recognised the Nansha Islands as China’s territory. In March 1987, under its Global Sea Level Observing System programme, UNESCO (the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) required the PRC to set up two permanent observation stations on the Nansha Islands.

On 4 September 1958 the Chinese government issued the Declaration on the Territorial Sea, stating that the territory of the PRC includes islands such as the Nansha Islands. In the same month, governments or official newspapers of Vietnam, the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, the German Democratic Republic, Mongolia and Romania also issued declarations or published editorials stating that they completely supported China’s decisions on its territorial seas (Han et al., 1988: 554–7).

Clearly, the international community has broadly acknowledged that the Nansha Islands are Chinese territory. Under international law, ‘recognition’ generates legal obligation in international relations. Thus acquiescence and recognition are of critical importance in territory disputes. In a specific dispute, if a party has given tacit consent to or recognised another party’s sovereignty over the disputed territory at a certain time, such recognition or acquiescence has a legal effect, as the party that consented or recognised the sovereignty in question cannot deny the other party’s sovereignty over the territory, and should respect the other party’s entitlement. Under international law, the legal principle is estoppel. A country which takes inconsistent positions is prevented from impairing the territorial title the other party enjoys.

This stance is supported by many scholars of international law. On estoppel or the ‘principle of preclusion’, Judge Jennings asserted that ‘there is completely no doubt that the principle has been accepted by international law’ (Wu, 2009: 51). Judge McNair also pointed out that ‘it is reasonable to hope that any legal regime would include such a regulation’ (ibid.). Ian Brownlie (1979: 164–5) valued estoppel as an established principle of international law based on ‘good faith’ and consistency. ‘The principle of estoppel. has been playing an important role in the cases on territory disputes accepted by the International Court of Justice…’ Estoppel is also called ‘exclusive principle’ in civil law. That is, ‘one party who makes acquiescence in a special status must keep its words thereafter’ (ibid.).

The principle of estoppel has been affirmed in many international judgments. A case in point is Eastern Greenland of the 1930s. Because the Norwegian foreign minister at that time made a remark about Denmark’s claim of sovereignty on 22 July 1917, saying his government ‘would not challenge over Denmark’s attempt on obtaining sovereignty over the Greenland Island’, the tribunal considered the Norway government to have made a commitment. Thus Norway has the duty not to raise a dispute over sovereignty of Greenland Island, or the occupied part of Greenland. The tribunal was clear in pointing out that ‘the reply made by the Foreign Minister of a country on behalf of his government to a foreign diplomatic delegation has obligation to the government he represents’ (Permanent Court of International Justice, 1933: 71–3).

When a head of government or senior official of a country makes a definite and unambiguous statement (a declaration or note) about a fact (especially about territory), this is made on behalf of the country, and the country is obliged to commit to the statement. The country should not evade the responsibility it has promised under the veil of wartime need. According to the principle of estoppel or preclusion in international law, when a party of the SCS dispute such as Vietnam officially recognises China’s sovereignty over the Nansha Islands, it has no right to claim title to the same thereafter. It is utterly against international law.

Where countries are not involved in the dispute but have recognised China’s sovereignty, such recognition entrenches the position of these third parties in the dispute. This is of critical importance. Because the United States and Japan have recognised that the Nansha Islands are China’s territory, they should observe the principles of international law and adhere to their original promise.

Protest against foreign invasions and fighting against foreign troops

The Chinese government has tried hard to protect sovereignty over the Nansha Islands. When other claimant states began occupying the islands, it continued to assert China’s inarguable sovereignty over them, as shown in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2

China’s protests against foreign invasions and fighting against foreign troops, focusing on period from Qing dynasty (chronological order)

| Period | Facts about foreign countries | Facts about Chinese government’s response |

| Qing dynasty (1644–1911) | In 1883 the Germans surveyed and investigated the features in the SCS In 1907 the Japanese developed the natural resources on the Dongsha Islands |

The Qing government protested to the German government and managed to stop the activities Immediately the Qing government sent troops to patrol the Dongsha Islands and held a ceremony to erect a monument of sovereignty on the islands |

| ROC period (1911–1949) | In the 1930s the French invaded the nine small features in the SCS During the Second World War Japan invaded the Nansha and Xisha Islands |

The Chinese government protested to the French government, and Chinese fishermen organised protests Both the Cairo Declaration and the Potsdam Declaration were clear in stating Japan’s obligation to return territory it had seized from China; to protest against Western countries such as the United States and Britain, which tried to exclude China from their negotiations with Japan on the Treaty of Peace with Japan, the foreign minister of China made a statement: ‘Thus, the Government of the People’s Republic of China declares, whether there are provisions or not and no matter what provisions are in the draft of the Peace Treaty with Japan, China’s inviolable sovereignty over the Nansha Islands and the Xisha Islands shall not be affected.’ |

| PRC (1949 to date) | On 17 May 1950 Elpidio Quirino, president of the Philippines, declared the Nansha Islands should be under the jurisdiction of the closest country, and that the Philippines was the closest country to Tuansha Qundao (Nansha Islands). | A spokesman of the Chinese government stated that ‘the provocateurs in the Philippines and their supporters in the United States must give up their dangerous plan, as it may lead to serious consequences. The People’s Republic of China will never tolerate the encroachment of the Nansha Islands and other features in the South China Sea by foreign countries’ (People’s Daily, 1950) |

| In May 1956 Carlos Garcia, foreign minister of the Philippines, said at a press conference that the group of islands in the SCS, including Itu Aba Island and the ‘Spratly Islands’ ‘belong’ to the Philippines, because it is the closest country to those islands (Wu, 2009: 52) | On 29 May a spokesman of the PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs declared that it was intolerable for China’s legal sovereignty over the Nansha Islands to be encroached by foreign countries under any excuse or in any way (Wu, 2009: 5) | |

| On 11 July 1971 President Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines stated at a press conference in Manila that the Nansha Islands was a group of ‘disputed’ islands, and announced that the Philippines had sent troops to occupy several of the major islands in the SCS | On 16 July 1971 the chief of staff of the People’s Liberation Army remarked at a reception hosted by the North Korean ambassador to China that China has inarguable legal sovereignty over the islands in the SCS, including the Nansha Islands; the Philippines government must stop its invasion of China’s territory and withdraw its troops and staff from the Nansha Islands (People’s Daily, 1971) | |

| In September 1973 the Saigon authorities of Vietnam included the Nansha Islands under Vietnam’s jurisdiction; several months later the Saigon authorities sent several hundred soldiers to occupy five features, including the Nansha Islands | On 11 January 1974 a spokesman for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a statement condemning the invasion by South Vietnam and reasserting China’s sovereignty over the Nansha Islands and other features in the SCS (People’s Daily, 1974a) | |

| In early 1974 the Saigon authorities sent navy and air forces to invade the Xisha Islands | On 20 January the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China asserted China’s sovereignty over the islands in the SCS (People’s Daily, 1974b) | |

| On 1 February 1974 the Saigon authorities sent warships to occupy Southwest Cay and other features of the Nansha Islands, and erected a ‘monument of sovereignty’ | On 4 February a spokesman of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs condemned and protested against Saigon’s conduct (People’s Daily, 1974c). On 30 March 1974, at the 30th Conference of the UN Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East, Ji Long, deputy representative of the Chinese delegation, issued a statement refuting a claim by the representative of the Saigon authorities regarding the Nansha Islands, and demanding that the conference secretariat correct the mistake | |

| In a resolution passed by the UN Regional Cartographic Conference for Asia and the Far East it was suggested that a South China Sea Hydrographic Commission be established, and that the hydrographic survey should include the Nansha Islands and surrounding sea areas (Wu, 2009: 52) | On 6 May 1974, at the 56th ECOSOC Conference, Wang Zichuan, representative of China, issued a statement restating China’s sovereignty over the SCS features and jurisdiction over the relevant waters, and demanding that the relevant authority cease survey in the SCS by the so-called South China Sea Hydrographic Commission and ensure that such incidents do not happen any more (Wu, 2009: 64); on 2 July 1974, at the Third UN Conference on the Law of the Sea, Cai Shupan, leader of the Chinese delegation, reasserted China’s sovereignty over the features in the SCS | |

| In May 1974 the Philippines announced oil exploration plans in the Nansha Islands (Wu, 2009: 64) | On 14 June 1976 the PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a sovereignty declaration; on 19 December 1978 a spokesman of the ministry was authorised to issue a declaration regarding China’s sovereignty over the Nansha Islands, reiterating that the islands had always been China’s territory and any claim of sovereignty over the Nansha Islands by other countries is illegal and invalid (Wu, 2009: 53) | |

| In 1979 Vietnam issued the White Book (Vietnam’s Sovereignty over the Huangsha and Changsha Archipelagos) | On 26 April 1979 Han Nianlong, head of the Chinese government delegation and Foreign Ministry vice-minister, spoke at the second plenary meeting of the Sino-Vietnamese Negotiations in Hanoi: ‘Both the Xisha Islands and Nansha Islands have always been an inalienable part of China’s territory. The Vietnam government should adhere to its former position and respect China’s sovereignty over these two islands, and should withdraw all its personnel from the features of the Nansha Islands’ (Wu, 2009: 53) | |

| In July 1980 the Soviet Union and Vietnam signed an agreement on cooperation in exploring and exploiting petroleum and natural gas ‘on the continental shelf of South Vietnam’ | On 21 July 1980 a spokesman for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a statement saying that engaging in exploration, exploitation and other activities in the sea area in the SCS without the approval of the Chinese government is illegal. ‘All agreements or contracts signed between nations regarding the exploration and exploitation of petroleum and natural gas in the above mentioned area are invalid’ (People’s Daily, 1980) | |

| At the beginning of April 1988 Vietnam seized three islands and reefs, and constructed military facilities on the Nansha Islands | China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a statement in mid-May 1988, sternly demanding that Vietnam immediately withdraw from the islands and reefs it had seized from China | |

| In June 1994 Vietnam deployed ships to conduct geophysical survey on the Vanguard Bank | On 16 June 1994 Shen Guofang, spokesman for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, remarked that China’s sovereignty over the Nansha Islands and its surrounding sea areas is incontestable; the Vanguard Bank is part of the Nansha Islands (Wu, 2009: 53) |

Critical date

Critical date is ‘the date at which a dispute between the two parties becomes crystallized and after which no acts can be taken into account in determining sovereignty’ (Dixon, 2007: 158). It is useful in that it provides a definite point at which sovereignty is to be finally determined. It is also the date after which actions of the parties to a dispute can no longer affect the issue (Johnson, 1950: 332). It is exclusionary and terminal, hence it is most frequently resorted to in territorial disputes to indicate the period within which a party should be able to show the consolidation of its title or its fulfilment of the requirement of the doctrine of occupation. The traditional use of the term ‘critical date’ may appear to import little more than the point of time in the course of an international dispute when the parties reject other possible means of resolving their differences and, defining them in terms of legal dialectic, reduce these differences to ‘objects of litigation’ (de Visscher, 1957: 79).2

Two famous cases related to ‘critical date’ are those concerning Palmas Island and the legal status of Eastern Greenland Island.

Palmas Island case

Palmas Island was a dispute between the United States and the Netherlands argued before the famous Swiss jurist Max Huber, who acted for the Permanent Court of Arbitration. Both the United States and the Netherlands claimed the small island of Palmas (or Miangas), which lies only some 48 miles southeast of Mindanao in the Philippines. The United States argued that Palmas was part of the Philippine archipelago, on the grounds of its geographical contiguity and its alleged former subjection to Spanish sovereignty – to which the United States had succeeded under the 1898 Treaty of Paris.3 This sovereignty, so the United States argued, had continued from the discoveries made and title acquired by Spanish navigators in the first half of the sixteenth century – discovery being sufficient to establish sovereignty under the international law of that time. The United States further contended that once acquired, this sovereignty had never been subsequently lost.

The Netherlands asserted, by contrast, that by the date of the 1898 treaty Spain had lost any sovereignty it may have once had over the island, and could grant no better title to the United States than it had on the date of the transfer of sovereignty. The Netherlands also contended that by 1898 the island had been effectively occupied as its territory. Huber decided in favour of the Netherlands on the ground that Spain had not consolidated its sovereignty by occupation as ruled by developing international law (Goldie, 1963: 1257). The Spanish discovery, without more, was insufficient to support a continuing title once discovery ceased to provide a basis for the acquisition of territory. In contrast the Netherlands had, by its occupation of the island, established sovereignty over it. Finally, any possibility that the United States might have consolidated Spain’s original and inchoate title by means of General Wood’s visit to the island in 1906, and acts subsequent thereto, was excluded by the arbitrator setting the critical date at 1898.

Since the United States could only claim as the successor of Spain, the date of the treaty transferring sovereignty was the last point in time at which Spain could have manifested sovereignty and established its title. The events which converged to indicate and identify the critical date were, on the one hand, the definitive and conclusive acts of sovereignty by the Netherlands operating in competition with Spain’s inchoate title and inconclusive acts, and, on the other, the transfer of sovereignty over the Philippine archipelago in the 1898 treaty (ibid.: 1258).

Legal status of Eastern Greenland Island

On the legal status of the Eastern Greenland case, ‘the Permanent Court of International Justice determined upon July 10, 1931, as the critical date – this being the date Norway proclaimed her sovereignty over the disputed area’ (Wu, 1999: 50). This time was indicated as the critical date by the convergence of each party’s acts of apprehension of the territory. It marked the turning point of the two claims. If Denmark had already established a definitive title over the territories in dispute, Norway’s proclamation was invalid in international law. But since Norway’s formal act of apprehension was constituted by the proclamation, Denmark had up to the date of the proclamation to establish its sovereignty and, if necessary, to convert it from an inchoate to a definitive title. If, on the other hand, Denmark failed to establish exclusive sovereignty by that date, Norway would have been entitled to establish its sovereignty thereafter by all appropriate means (Goldie, 1963: 1259).

Discussion

These two cases show that the practice of international law does not require ascertainment of ‘the exact time’ that jurisdiction of sovereignty begins, but attaches importance to which party was exercising jurisdiction more effectively within a reasonable period of time (usually about 200 years) before the dispute occurs (critical date). In Eastern Greenland the court determined that 10 July 1931 was the critical date because Norway declared that it had occupied the area; before that date, no country had claimed sovereignty over Eastern Greenland Island except Denmark. Thus the territory dispute on the island started on that day. As Denmark had exercised more effective jurisdiction on Eastern Greenland Island for a certain period before the critical date, the Permanent Court of International Justice decided that the territory belongs to Denmark.

In Palmas Island Judge Huber determined that 10 December 1898 was the critical date because that was when Spain and the United States signed the Treaty of Paris and recognised that the Philippines was a US colony. The focus of the argument was whether Spain or the Netherlands had exercised more effective jurisdiction over the island. Since the Netherlands had exercised sovereignty over Palmas Island peacefully and over a continued period during the 200 years before 1898, the judges decided the island had belonged to the Netherlands before the critical date and could not be ceded to the United States from Spain by reason of the Treaty of Paris.

According to this judicial precedent, the author believes the ‘critical dates’ for the Nansha dispute are 25 July 1933 (the date France announced that it had occupied nine islands in the Nansha group on the grounds of terra nullius) and 9 April 1939 (the date on which Japan formally declared that it had occupied the Nansha Islands and changed their name to Xinnan Qundao). If one can prove that the challenges by both France and Japan to China’s sovereignty over the Nansha Islands are illegal and invalid, this would prove from another angle that China’s sovereignty over the islands is unarguable.

The object of any ‘preoccupation’ must be a piece of land without an owner. But the nine features do not have any characteristic in common with terra nullius under international law. Chinese fishermen from Hainan engaged in fishing the Nansha sea area and settled on the Nansha Islands long ago. According to records, the British ship Rifleman arrived at the Nansha Islands to conduct surveys without the permission of the Chinese government. According to the British, there was evidence on every island that fishermen from Hainan had been living there and collected trepang and seashells for a livelihood. Some fishermen lived there the entire year. Ships from Hainan visited every year, bringing rice, food and other daily necessities to exchange for trepang and seashells with the fishermen on the islands (Wu, 1999: 51). Several versions of the China Sea Pilot edited by the Hydrographic Office of the British Admiralty stated: ‘An island, named Sin Cowe, is said by the fishermen to lie about 30 miles to the south of Namyit’ (ibid.).

Between 1930 and 1933, the period when the French invaded the nine features, they also acknowledged that there were only Chinese fishermen living on the islands. The periodical Colonizing World published in 1933 recorded that when the French warship Malicieuse surveyed the Nansha group, there were three Chinese fishermen living on the island (Wu, 1999: 51). In April 1933, when the French invaded the Nansha features, the residents there were Chinese: seven people on Southwest Cay, five on Thitu Island and four on the Nansha Islands, plus huts, wells and temples left behind by the Chinese on Loaita Island (ibid.: 14).

Before the French arrived at the Nansha Islands in 1930, many Japanese books and periodicals documented the production activities of Chinese fishermen on the islands. For instance, it is recorded in Xin Nan Qun Dao Yan Ge Lue Ji, a document deposited with the Archive Department of the Taiwan Administration, that there were two Chinese tombstones on Northeast Cay. One was erected for Weng Wenqiong in the eleventh year and the other for someone with the surname Wu in the thirteenth year of Emperor Tongzhi’s era (1872 and 1874 AD, respectively) during the Qing dynasty. In December 1918 the Lhasa Phosphorite Company of Japan organised an ‘expedition’ to explore the Nansha Islands. Upon returning to Japan, one member of the expedition, Ogura Unosuke, wrote a book called The Storm Island (Ogura, 1940), in which he described having met three fishermen from Hainan Island on his first day on ‘North Danger’. He asked the fishermen when they arrived on the island and where they lived. They replied that they had arrived two years earlier, and lived in huts. Asked what they did there, they said they collected trepang. They also said that large ships from Hainan Island arrived at the islands every December or January (Chinese lunar calendar) to bring back their harvest. Every March or April (Chinese lunar calendar) other fishermen would come to replace them. The three fishermen had a rough map of the Nansha Islands, and one had a compass with 12 points of orientation (Wu, 2009: 54). The fishermen’s map of Nansha was printed in The Storm Island. It indicated ten names of islands, reefs, cays and banks, noted in local terms used by fishermen from Hainan Island and still used by Hainan fishermen in Geng Lu Pu (a directory for fishing and navigation): Nanshan Island, West York Island, Northeast Cay, Southwest Cay, Thitu Island, Loaita Island, Sin Cowe Island, Ituaba Island, Namyit Island and Irving Reef.

As discussed, there was habitation on the nine features in the Nansha Islands, and additionally there are records of a country exercising sovereignty over the islands. This means that the Nansha Islands do not share any common characteristics with a terra nullius under international law and cannot be an object for ‘preoccupation’.

After the Second World War the Chinese government ordered the Japanese troops stationed on the Nansha Islands to surrender to Chinese troops at Yulin Port. When the Japanese troops gathered at Yulin Port waiting to be deported to Japan, the French occupied several features in the Nansha Islands until China sent troops to take them over. On 27 July 1946 a ship of unidentified nationality invaded the Nansha group. The Central News Agency of China reported that ‘the Navy Headquarters decided to send warships for a second patrol in the South China Sea after taking back the islands’ (Wu, 1999: 51). The Chinese government ordered the ship to leave the islands within a few days. On 5 October the same year the French warship Chevreud invaded Nanwei Island and Itu Aba Island, and erected memorial stones on them. The Chinese government negotiated with France on the sovereignty of the SCS features in October 1946 and January 1947. Eventually, negotiations were suspended because the French government could not provide any effective evidence to support its claim to sovereignty over the Nansha Islands.

The impact of UNCLOS

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea is often referred to as the constitution for the oceans. It establishes a number of maritime zones and regulates the rights and obligations of states as well as other users of the sea. After nine years of tortuous negotiations beginning in 1974, it was adopted in 1982 and entered into force on 16 November 1994. There are in total 162 state adopters at the time of writing, including all claimant states of the South China Sea: China, Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines and Brunei.4 Because Taiwan is not recognised as a state by the United Nations, it is not able to ratify the convention.

The sovereignty of island features lies at the heart of the SCS dispute and may become the most dangerous flashpoint in the region. Despite its widely discussed relevance to the dispute, UNCLOS is not able to resolve this core issue given its limitations, namely its inability to determine sovereignty over island territories. Yet the convention does have a role to play, as discussed below.

Islands involved in the SCS dispute are extremely significant not only for the sensitive sovereignty issue they engender, but also because they generate maritime zones that are crucial to the delimitation between coastal states. On this subject, UNCLOS Article 121 provides for a regime of islands:

![]() An island is a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide.

An island is a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide.

![]() Except as provided for in paragraph 3, the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf of an island are determined in accordance with the provisions of this Convention applicable to other land territory.

Except as provided for in paragraph 3, the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf of an island are determined in accordance with the provisions of this Convention applicable to other land territory.

![]() Rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.

Rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.

While Article 121 sets out the regime of islands, it is difficult to apply it to the SCS. This difficulty is twofold. First, the provisions are ambiguous and so far lack authoritative interpretation, in particular of ‘sustain human habitation or economic life of their own’. Second, the exact number and geographic condition of the SCS features remain unclear and may vary over time.

Itu Aba (Taiping Island), the biggest feature in the Nansha Islands, might fulfil the requirements of the island regime and be able to generate its own EEZ and continental shelf, as Song (2011) states. Other island formations can almost certainly fall under the sway of Article 121(3) (Elferink, 2001: 182). The number of features that could be entitled to an EEZ and continental shelf is still unknown. Furthermore, it is worth noting a trend towards reducing the effect of sparsely inhabited islands in the state practice of delimiting maritime boundaries. Thus, as Hong (2012: 58) argues, it seems quite likely that even if some of the claimant states should succeed in their sovereignty claims, they would achieve little from the victory.

As to the South China Sea disputants, not all of them make clear whether or not they will apply the regime of islands to the occupied features. On 6 May 2009 Malaysia and Vietnam submitted jointly to the CLCS information on the limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nm. But since the EEZ claimed in the submission is from the baselines of their mainland coasts rather than the island features occupied, some scholars interpreted it as an official stance of not applying the island regime (Beckman and Davenport, 2011). Yet this assumption is still without confirmation from any relevant authorities.

Another core issue of the SCS disputes is the delimitation of the maritime zones of EEZ and continental shelf. Unclear ocean boundaries between states may result in severe conflict of competing jurisdictional activities, especially over living and non-living resources. Principles set out in UNCLOS govern the delimitation of maritime boundaries between opposite and adjacent states where maritime zones overlap: Article 15 provides a relatively clear method of delimiting territorial sea boundary using a median line, but the highly similar wording of Articles 74 and 83 emphasises that the purpose of the delimitation is to achieve an ‘equitable solution’ rather than to function as a real method or procedure for delimitation. Therefore the customary international laws on delimitation established and developed by courts and tribunals are of great importance.

What makes the demarcation of the maritime zone of the SCS extremely difficult is not the confusing principles, but the unresolved sovereignty dispute over the features. Whether these islands and rocks scattered in the SCS have the intrinsic value of generating maritime spaces of their own is a matter of debate. International courts and tribunals have been faced with the question of the relevance of small offshore islands in the delimitation of maritime boundaries. Observations from judgments in cases dealing with this question indicate that islands are given less precedence when resolving overlapping maritime claims between an EEZ measured from a small and remote island and an EEZ measured from the mainland. Yet the judgment released on 14 March 2012 in the Bangladesh/Myanmar case on the effect of St Martin Island in delimitation is highly controversial when its important economic life and geographical location are considered.5 The situation in the South China Sea is much more complicated than that in the Bay of Bengal. While small and insignificant features in the SCS may reasonably be given very limited effect in demarcation, the bigger islands such as Itu Aba still have a chance of winning their own maritime space.

As to claims for extended continental shelves, several states in the region have submitted their information to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. Coastal states are competing with each other for jurisdiction over the continental shelf for the purpose of exploiting and exploring the potential hydrocarbon resources. As permitted by Article 76, by submitting technical information to the CLCS, states can make continental shelf claims beyond 200 nm, out to a maximum of 350 nm or even further. On 6 May 2009 Malaysia and Vietnam made a joint submission on a ‘defined area’ in the southern part of the SCS. On 7 May 2009 Vietnam made a partial submission relating to the ‘North Area’ in the northwest of the SCS (Malaysia/Vietnam, 2009;Nguyen and Amer, 2009: 251). It is worth mentioning that before making a recommendation on submissions in disputed areas, the CLCS requires that consent be given by all disputant states. Also, the role of such a recommendation in the delimitation between states with opposite or adjacent coasts is still unclear.

Part XV of UNCLOS established perhaps the most complex dispute settlement system ever included in any global convention. Some commentators believe that the regime set out in Part XV is comprehensive and constantly in operation to ensure the smooth functioning of UNCLOS, while others remain sceptical as to the scope and effectiveness of the regime as a whole in balancing a myriad of competing needs for dispute settlements dealing with different maritime zones and different maritime activities (Boyle, 1997: 38; Klein, 2005: 3).

As a result of the balance, some highly sensitive parts of each issue area can be excluded from mandatory jurisdiction. Section 3 of Part XV provides for exceptions and limitations to the system; in particular, Article 297 excludes two types of disputes from the system – fisheries and marine scientific research. Furthermore, Article 298 gives state parties the right to opt out of certain categories of disputes. China has exercised this right by submitting a declaration on 25 August 2006, opting out of the disputes referred to in paragraph 1(a)–(c) of Article 298 in regard to maritime delimitation, historic title, military activities and others.6 In view of the fact that any dispute in the SCS will unavoidably involve unsettled sovereignty issues over the islands – features which are excluded from submission to conciliation and outside the reach of the mandatory dispute settlement regime – the role that Part XV can play in resolving this ongoing situation is very limited.

U-shaped line

The ‘U-shaped line’ (Figure 3.1) refers to a line with nine segments off the Chinese coast in the SCS, as marked on Chinese maps. It is also known as the ‘nine-dotted line’, ‘nine-dash line’ and ‘China’s traditional maritime boundary line’ in different sources. The line begins from the maritime boundary between China and Vietnam next to Beibu Bay, extends southwards to include a U-shaped maritime zone, and then meets the Chinese boundary line to the East China Sea and Yellow Sea. This section traces back the birth and evolution of the line and China’s state practice, and critically reviews the four major scholarly interpretations.

Figure 3.1 The U-shaped line Source: Taken from China’s Note CML/17/2009; available at: www.un.org/Depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mysvnm33_09/chn_2009re_mys_vnm_e.pdf (accessed: 19 June 2012).

History of the U-shaped line

The line was compiled by a Chinese cartographer, Hu Jinjie, including only the Dongsha and Xisha Islands at the time, and later published during the 1920s and 1930s (Zou, 1999a: 32). The first modification of the line happened in 1933 after the occupation of nine small features of the Nansha Islands by France, the then protector of Vietnam. After protest to the French embassy (Republic of China, 1934) to demonstrate China’s sovereignty over the Nansha Islands, the line was stretched south to 7–9° N latitude (Wu, 2001: 33). The second version of the line was drawn by the Committee of Examining the Water and Land Maps of the Republic of China in 1935, extending further south to 4° N latitude and incorporating Zengmu Ansha (James Shoal) for the first time. The committee at the same time published the names of the features of all four island groups (ibid.: 13). Chinese scholars often consider this act as a governmental declaration of China’s maritime boundary and the Nansha Islands as China’s southernmost territories (Zou, 1999a: 33). One of the maps most cited by historians is New China’s Construction Atlas, published in 1936 and edited by a well-known geographer, Bai Meichu, who compiled the atlas based on the committee’s publication (ibid.).

On 1 December 1947 the ROC government published a map of the archipelagos of the South China Sea; this is widely recognised as the first official map showing China’s claims (Valencia et al., 1999: 24). There are two distinguishing characteristics of the line in this map: it included James Shoal and ended at 4° N latitude in the south; and 11 dotted lines replaced the previous continuing line (ibid.: 33). Though giving no explanation of why the line was drawn or modified, Zou (1999a: 34) made an assumption that each extension of the line was a ‘reaction to the challenges or encroachments made by foreign intruders to the Chinese claims of sovereignty and jurisdiction of the islands in the South China Sea’: the recovery of the Dongsha Islands from the Japanese in 1914, French occupation in 1935 and the end of the Second World War in 1945. The map remained the same after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, and then in 1953 two of the 11 segments in Beibu Bay were eliminated without any official explanations (Wu, 2009: 35).

China’s state practice regarding the U-shaped line

In 1958 China declared that the four groups of the Dongsha, Xisha, Zhongsha and Nansha Islands all belonged to China according to the Declaration on China’s Territorial Sea (Zou, 1999a: 35).7 Yet the declaration itself did not mention the U-shaped line. In 1992 China promulgated the Law on Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone, which sets out the breadth of the territorial sea as 12 nm, measured from the straight baselines of the coast.8 In May 1996 China officially published part of its mainland coast and Xisha straight baselines with 28 base points.9 In 1998 China promulgated the Law on Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf, in which ‘historic right’ is mentioned without definition.10 This generated a long-lasting debate on China’s historic right claim, assessed below.

The debate over the U-shaped line was reignited in 2009. On 6 May Malaysia and Vietnam jointly submitted information on the outer limit of the continental shelf to the CLCS. China protested against the submission, and in a letter to the Secretary-General enclosed the U-shaped line map (China, 2009; see Figure 3.1). Paragraph 2 of the letter provides:

China has indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters, and enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the relevant waters as well as the seabed and subsoil thereof (see attached map). The above position is consistently held by the Chinese Government, and is widely known by the international community.

The map generated another round of intensive and long-lasting debate over the legal basis of the U-shaped line and the legality of China’s claim.

Interpretations and concerns regarding the U-shaped line

Over the years there has been a wealth of literature on the interpretation of the U-shaped line. Chinese scholars categorised Chinese academic interpretations of the line into four groups: line of traditional maritime boundary, line of historic waters, line of historic rights and line of ownership of the features. These views are critically assessed below.

Traditional maritime boundary line

Li and Li (2003: 294) refer to the U-shaped line as the ‘Chinese traditional maritime boundary line in the SCS’, arguing that the line was drawn in the middle between the features at the outer edge of the archipelagos and the coastline of neighbouring adjacent nations, and was a claimed national boundary. Therefore it has a ‘dual nature’ of claiming China’s sovereignty over all the features within the line and also marking China’s maritime boundary. Zhao Guocai (1998: 22), a professor of Taiwan Politics University, seems to hold the same view. However, a boundary line must be continuous. The segments can hardly be justified as a settled boundary line at sea.

Line of historic waters

When the Taiwan authorities issued the SCS Policy Guidelines in 1993 (Central Daily News, 1993), the water areas within the U-shaped line were given the status of historic waters. The guidelines stated that ‘the SCS area within the historic water limit is the maritime area under the jurisdiction of the Republic of China, in which the Republic of China possesses all rights and interests’ (Sun, 1995: 408; Zou, 2001: 160). This may be construed as Taiwan’s official position on the concept of historic waters, although its claim has not received unanimous support within Taiwan academia.

Zou (ibid.: 162) argues that neither mainland China nor Taiwan has exercised authority in the area frequently since the promulgation of the line. Even the occasional exercise of authority focused on the islands within the line rather than on the water areas. The freedom of navigation and of fishery seem to be unaffected by such activity. Thus ‘the question of whether there is effective control over the area within the line so as to establish it as historic waters arises’ (ibid.).

Fu (1995: 42) proposes a creative interpretation, arguing that the legal status of the waters within the U-shaped line should be a maritime zone of ‘special historic waters’ distinct from all maritime zones established by UNCLOS, i.e. internal waters, territorial sea and EEZ. He further argues that the regime should and could be established as time and law evolve.

Line of historic rights

Article 14 of the 1998 Law on Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf claims China’s historic rights in the SCS. Amid intensive discussions in the academic world, Zou (2001) did a comprehensive study on ‘historic rights’ and found two types of rights: one exclusive with complete sovereignty, such as historic waters and historic bays; the other non-exclusive without complete sovereignty, like historic fishing rights in the high seas (ibid.: 160). He argued that China’s claim of historic rights is distinguished from the two, as to be ‘historic rights with tempered sovereignty’, and points out:

Such sovereign rights are exclusive for the purpose of development of natural resources in the sea area and jurisdiction in respect of marine scientific research, installation of artificial islands, and protection of the marine environment. It is obvious that such a claim to historic rights is not only a right to fisheries, but to other resources and activities as well.

In the author’s understanding, the concept of historic rights is clearly different from the concept of historic waters. It should include sovereign rights over living and non-living resources and the quality of the marine environment. China has been showing its willingness to negotiate the issue of joint development and resource sharing, thus the extent of the ‘historic right’ claim is subject to negotiation.

Line of ownership of the features

Judge Gao Zhiguo, the judge of Chinese nationality on the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, concluded in a 1994 article that China claims only the islands and their surrounding waters within the U-shaped line, rather than the entire water column of the South China Sea (Gao, 1994: 346).11 Hasjim Djalal, a former Indonesian ambassador and expert on the law of the sea, questioned the legal basis of the line and argued that China’s original claim using the line was only the islands and rocks, instead of the waters enclosed (Djalal, 1995).

It is worth noting that Judge Gao’s view regarding the line has changed and become more flexible. In a recently published paper he argued that it is reasonable to say the U-shaped line ‘has become synonymous with a claim of sovereignty over the island groups, and with an additional Chinese claim of historical rights of fishing, navigation, and other marine activities. on the islands and in the adjacent waters. The line may also have a residual function as potential maritime delimitation boundaries’ (Gao and Jia, 2013: 108).

In the author’s view, it seems that the interpretation of ‘ownership of the features’ is more acceptable to an international audience, and forestalls any doubts that China will use the ambiguous terms ‘historic title’ or ‘historic rights’ to maximise its own interest in the SCS. However, the debate will continue if China remains silent and keeps its claim ambiguous.

1Inter-temporal law is a concept in the field of legal theory. It deals with the complications caused by alleged abuse or violation of collective or individual rights in the historical past in a territory whose legal system has undergone significant changes, and for which redress along the lines of the current legal regime is virtually impossible.

2For a discussion of the terms ‘legal dialectic’ and ‘object of litigation’ see de Visscher (1957: 79). See also Goldie (1963).

3The date of the Treaty of Paris, under Article HI of which the Philippines archipelago was surrendered by Spain to the United States and was delineated, as far as the claims of the parties inter se were concerned.

4More information on the convention is available at www.un.org/zh/law/sea/ los/index.shtml (accessed: 5 June 2013).

5St Martin is given full effect in the final demarcation of territorial sea but zero effect for EEZ and continental shelf. Information on the case is available at www.itlos.org/index.php?id = 108&L = 0 (accessed: 12 December 2012).

6The up-to-date official texts of declarations and statements which contain optional exceptions to the applicability of Part XV, section 2, under Article 298 of UNCLOS are available at www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_declarations.htm#China%20Upon%20ratification (accessed: 5 June 2013).