11

The Rehearsal/Blocking Script

The rehearsal script is the script the SM creates during the rehearsal period at the rehearsal hall. It is the SM’s bible to what the performers will do in the show and what the director has conceived. In it are noted the actors’ blocking, technical cues, prop placement, preliminary notes on some of the scene change moves, characterization and motivation notes prescribed by the director, all changes the director might make in the dialogue or script, and a copy of the SM’s personal floor plans.

Learning the Show and Gathering Information

Before work can begin on the rehearsal script, the SM must become knowledgeable of all parts of the show. This is accomplished by reading the script the first time as an entertainment piece, and then by gathering whatever information can be gathered from the producer, director, designers, and heads of the different technical departments.

This information may come in giant chunks or dribbles. At this point the SM has a “sketchy” idea of the play. Now it is time to start putting the pieces together, and that starts with the second and even third reading of the play: the plot development, the sequences of events, the action, the characters, and the journey the characters take. From these next readings, the SM creates beginning drafts of the prop list, character list, and the Scene/Character Tracking Chart, with which by now you should be quite familiar (see Chapter 6, “Hard Copy”). During these first readings, the SM notes in the script, in the right-hand margin, all technical cues inherent to the script, such as a doorbell ring, telephone ring, offstage sound-effect cue, lighting effect, blackouts, and so on. With the first note the SM makes in the script, it becomes the rehearsal script. (See Fig. 11-25 later in this chapter.)

Set Design

Before rehearsals begin, the SM must know as much about the design and layout of the set as the set designer. The SM must mentally marry the design of the set to the script and be ready to answer any question that might come up in the rehearsal hall. From the set designer, the SM gets scenic drawings, the floor plans, and whatever sketches or scale models the designer might have made. From this information, the SM creates personal floor plans, which we also worked through in Chapter 6, “Hard Copy.”

Costumes

The more knowledge the SM has about the production before going into rehearsals, the better. The SM might want to set up a meeting with the costume designer. If the show is a contemporary piece, this meeting may not be necessary. However, if the show is a period piece, the SM should get an idea of how cumbersome or restrictive the costumes might be. Also, the SM might now consider making arrangements to have long rehearsal skirts for the ladies, and if for the men a cape or hat is part of the business or action of the scene, then have those things too. The SM might also ask the designer about the footwear, and if wearing them is going to need some getting used to, the SM might ask if some facsimile could be had for rehearsals. With all of that being done, the SM should also ask the designer for any sketches or renderings that could be put up on display in the rehearsal hall for at least a couple of days.

Music

If the show is a musical that has already been produced, the SM should become as familiar with the music as with the script. More than likely there is an original cast album that can be purchased, if the SM does not already have it. If the musical show is being produced for the first time, more than likely the SM, along with the cast, will be learning it for the first time as it is played in a first reading or as it is being learned in the rehearsal room.

The SM’s quest for knowledge and information on the show is endless, but with just this suggested amount of information and work done, and with the rehearsal script in hand, the SM is ready to begin rehearsals. Remember, the rehearsal hall has already been set up in the last couple of days of the SM’s pre-production time.

Enter the Rehearsal/Blocking Script

The rehearsal script too was put together during the SM’s pre-production time. It now becomes the center of attention for the SM. A great part of the job now is to be seated at the SM’s worktable with pencil in hand noting the blocking. The greatest amount of information gathered and entered in the rehearsal script is the blocking of the show, so much so that the rehearsal script is also called the blocking script. Oftentimes noting the blocking can become the ASM’s job while the PSM is tending to all of the business surrounding the day and the production. So while this chapter is directed to a PSM, ASMs take note and follow along, because if put into this position, you will be required to do all that is said here.

Noting Choreography: Never in any musical production on which I have worked as the SM have I been required to note the choreography. I might on my personal-size floor plans note opening positions/picture of the performers/dancers, or possibly an important picture or placement of the dancers within the dance, and perhaps the closing picture, but never was I responsible for noting the actual steps, movement, and placement of the dancers. Now, with songs, I have noted within the written lyrics on the page the places on stage to which the singer moved, but nothing more.

Blocking is the noting and recording of all the movement, action, and business in the show, as set and agreed on by the director and actors. Blocking is noted in the rehearsal script for the express purpose of:

- Remembering all that was set and aiding the director and actors should they happen to forget

- Aiding the SM in preparing the understudies and putting in replacement actors

- For a new play, keeping a record of the director’s creation and invention

- Keeping an accurate account of the blocking as a historical account for the archives, for prosperity, and in part for the publication of the play (but the blocking notes included in the published script are never as detailed and extensive as the SM’s notes are in the blocking/rehearsal script)

While the actors write their own blocking on their personal scripts, the SM’s notes the blocking for every actor/character in the rehearsal script.

In professional situations and in most academic and community theatre, when a director directs a show that has been previously produced, the blocking that is printed in the published script is seldom if ever used. If a director refers to the blocking done in another production, it is merely to see how another director handled a particular moment or difficult piece of business.

A Definition of Blocking

The World Book Dictionary has no definition for the word blocking as it is used in theatre. Under the term “block,” this definition is given in reference to blocking a hat: to give form and shape; to mount, mold, and shape. For an SM’s definition, this is a good beginning. Perhaps if we list some of the theatrical terms used around blocking we can come to a closer definition:

- staging

- stage directions

- stage business

- stage movement

- stage action

- stage picture

- timing

- traffic pattern

- shtick (comic business)

In more detail:

- Blocking is the visual design of movement in the play. It is the moving pictures and composition on the stage that enhance the play, the storyline, the action, the characters, the actors’ performances, and the entertainment value for the audience.

- Blocking is movement, action, and business deliberately set for each actor/character who appears on the stage.

- Blocking is set by the director and implemented, enhanced, and embellished by the actors.

- Blocking is the traffic pattern or floor plan of movement that takes place on the stage and within the scenery or stage setting.

- Blocking is handling props or moving furniture and set pieces during the performance, as seen by the audience.

- Blocking is doing bits of business, be it comic or dramatic.

Personal Blocking

There is also personal blocking—bits of business or action an actor does such as making a hand gesture or taking one or two steps. The SM might note this blocking in the script but would not try to impose it on another actor performing the same part.

Famous Blocking

Throughout the history of theatre, there are many famous and iconic scenes and bits of blocking or staging:

- The classic Romeo and Juliet balcony scene

- Many scenes in Fiddler on the Roof and A Chorus Line

- Hedda Gabbler burning the Lovborg manuscript

- The “head higher than king” scene between Anna and the King of Siam

- Finch’s scaffolding entrance at the beginning of How to Succeed in Business

It is important for the SM to know and understand blocking. It is an important part of the job that the SM must deal with throughout the rehearsal period and watch over during the run of the show.

The SM’s Responsibility for Noting Blocking

The actors are responsible for noting their blocking in their own scripts. From the first blocking rehearsal, the SM establishes that the blocking will be noted in the rehearsal script but reminds the actors of their responsibility for doing the same. If an SM should happen to work with a performer who insists the SM take down his or her blocking, and if the director approves of this way of working, the SM complies. However, as soon as possible, the SM sees that this information is also entered into the performer’s personal script. Even when the actors write in their own blocking, the director and actors are highly dependent on the SM for blocking information, especially when first running scenes without use of their scripts. They expect the SM to do this job thoroughly, accurately, completely, and to have the correct, most recent, and updated changes.

This is a monumental task that requires the SM to be seated at the SM’s worktable concentrated and noting into the blocking script all that is set. The SM’s greatest and most important tool while doing this part of the job is a sharpened pencil and a great big eraser—the kind that is smudge-proof, similar to the art gum that sketch artists use, and not the eraser on the other end of the pencil, which are notorious for digging into the paper. The one thing the SM can count on with noting blocking is that there will be change—if not within the next moment, surely down the line, be it the next day, two weeks later, or even after the show gets into the theatre and on the stage. Once again, I repeat: when there are two SMs on the show, this job is given to the ASM while the PSM is handling all other business.

The Speed Required for Making Blocking Notes

Noting blocking during rehearsals is one of the more challenging jobs. The SM must be totally focused and concentrated, watching and listening to everything the director and actors say and do as they work in the rehearsal. Neither the actors nor the director will stop their work to allow the SM time to take notes. The SM is expected to take notes without infringement or distraction on the actors’ and director’s time. All notes of blocking are done on the run, which means that anything missed by the SM must be gotten when the scene is run again on that day or in the next rehearsal days later, or by getting together with the actor at some other time when the actor is not rehearsing.

Noting Blocking Electronically

While there is talk of computer programs that can be used for noting blocking, I firmly believe that this is only for noting blocking after the show is open and after the show has become frozen. Unless the SM is a wiz at fingering the keyboard, it seems almost impossible to be entering blocking electronically and still keep up with the performers and the director as they create, change, go back, change, and re-create. At best, at this time, if an SM wants to have a blocking script that is completely digital, it appears that first the blocking needs to be noted manually, with pencil and eraser, and then once the show is set, these notes can be entered into the computer.

Regardless of whether things are done electronically or by hand, the vocabulary, the abbreviations, and the symbols needed to efficiently note blocking so that it can be read at a latter time and re-created as directed are what we will be dealing with in this chapter.

The SM’s Shorthand

With this kind of pace, the SM needs to have a quick method of noting—a shorthand. In addition to the limited time, the space on each page of the script for making the blocking notes is limited. To get the blocking noted, the SM must be brief and concise in the notes and at the same time provide the most detailed information so that it can be read and understood at a later time.

Noting blocking is a world of abbreviations, symbols, and handwritten diagrams. There is no standard written language or form to follow. There are some basic symbols or abbreviations used in theatre, but for the most part SMs develop their own. They learn from many sources: from their academic studies, from books such as this, from working with other SMs, and by making up their own.

The first and most basic knowledge every SM must have is the area breakdown of the stage and the abbreviations noting each area. Most people in theatre already know this information. However, let’s review, starting simply, and then becoming more detailed.

Knowing Your Right from Your Left

Above all things in the world of blocking, the SM must know which is stage right (SR) and which is stage left (SL). This must be firmly planted in every SM’s head. As well as knowing your name, you must also know that

- SR is always the actor’s right as the actor stands on the stage facing the audience.

- Conversely, SL is always the actor’s left as the actor stands on the stage facing the audience.

This reverse orientation in the natural order of things can be confusing to the beginning SM or any newcomer to the theatre. While noting blocking, it would be natural to use one’s own right or left. Don’t! Once again, SR is always the actor’s right as the actor stands on the stage facing the audience, and SL is always the actor’s left as the actor stands on the stage facing the audience. This also applies to when reading scenic drawings/floor plans, looking at artists’ renderings, or viewing a scale model.

House Right and House Left

To complicate this matter further, when talking about the placement of things in the audience (the house):

- The right side of the house (house right) is as a person sits in the audience to view the stage.

- Conversely, the left side of the house (house left) is as a person sits in the audience to view the stage.

It is especially important that the SM have these two areas firmly planted in mind because the SM, above most others, will be dealing with both areas.

To distinguish between what is right and left on stage and what is right and left in the audience (the house), and to be clear in communication, whether it be in noting blocking or having conversation, when the SM talks about the placement of things on the stage they are always described as stage right (SR) or stage left (SL). When talking about things in the audience, the SM always says house right (hs.R) or house left (hs.L).

Notice: While discussing the right and left of things, you have also been exposed to some of the SM’s shorthand notations: stage right (SR), stage left (SL), house right (hs.R), and house left (hs.L).

The Stage Breakdown

The Basic Parts

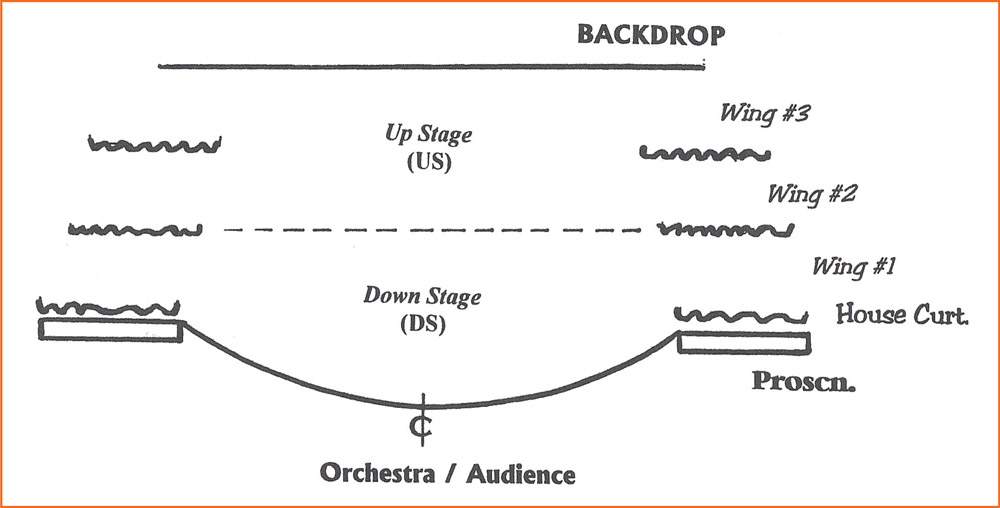

More than likely you already have a working knowledge of the terms and abbreviations that the SM will use in noting blocking or in communication. But for the sake of being thorough and complete, as is the nature of SMs, let’s start with the basic stage as shown in Figure 11-1.

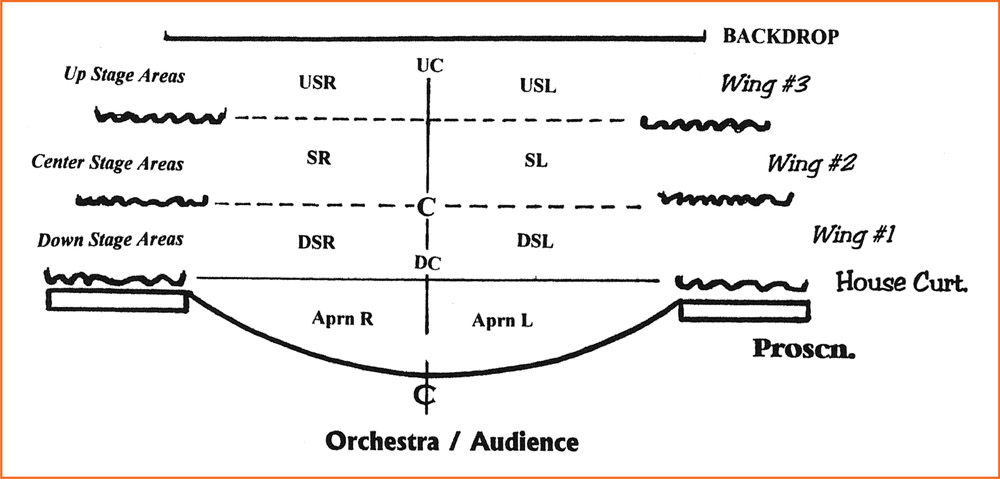

The Center Stage Line

The imaginary vertical line that travels from the audience up to the back of the stage and cuts the stage in half is the center stage line (see Fig. 11-2). If an actor were to stand at any point on this line facing out to the audience, everything to the actor’s right would be SR and anything to the left is SL. Note the symbol or letter C at the bottom of the dividing line. This is the abbreviation the SM uses in blocking notes to note the center position on the stage. The symbol for this center position is often written in one of three ways, as shown in Figure 11-3.

Figure 11-1

The basic parts of a stage.

The proscenium = proscn. The house curtain = hs.crt. Wings #1, #2, #3 = #1wng, etc

Figure 11-2

The center line vertically dividing the stage in half and creating stage right and stage left.

Different Symbols Used for Center Stage

Figure 11-3

The three different ways the center position of the stage is written.

Creating Up Stage and Down Stage

If the stage is divided in half horizontally, anything above the dividing line is up stage (US) and anything below is down stage (DS) (see Fig. 11-4). In addition to being areas on the stage, the terms upstage and downstage are also used to describe the direction in which anything travels on the stage. Anything on stage that moves away from the audience is traveling US. Conversely, anything that moves toward the audience is traveling DS.

Stage Divided Horizontally and Vertically

When the stage is divided with the vertical line and the horizontal line, four major playing/performing areas are created, as shown in Figure 11-5. With these imaginary lines drawn, you now have four performing areas:

- Down Stage Right = DSR

- Down Stage Left = DSL

- Up Stage Right = USR

- Up Stage Left = USL

In addition, three more performing areas are created and can be used in notating blocking:

- Up Center = UC (anything placed on that center line above the horizontal line, be it an actor, prop, or scenery)

- Down Center = DC (similarly, anything placed on this center line below the horizontal line, be it an actor, prop, or scenery)

- Dead Center = C (where the horizontal line and the vertical line cross, this becomes the center of the entire stage)

Remember these abbreviations; they will forever be part of your SMing life.

The Apron

The apron (aprn) of the stage is the part closest to the audience. It is the part that projects past the proscenium

Figure 11-4

Horizontally dividing the stage in half, creating the upstage (US) area and the downstage (DS) area.

Figure 11-5

Dividing the stage with the vertical and horizontal lines, creating four major performing areas on the stage. Where the two dividing lines meet, that point becomes the center (C) of the stage. Anything above this center point is called up center (UC), and anything below is down center (DC).

Figure 11-6

Creating the apron (Aprn) part of the stage.

arch out into the audience (see Fig. 11-6). When the house curtain is drawn across the proscenium opening, the apron is that part of the stage floor that remains in view of the audience. It can be several feet deep, or be as narrow as a few inches. It can arch out into the audience (as in our diagrams), it can be straight across, or it can be constructed to suit the imagination of a designer. In dramas and comedies with traditionally designed sets, such as the interior of a room or apartment, this part of the stage is seldom used. Broadway musical shows will use this area more, while variety art and vaudeville shows put this space to greatest use.

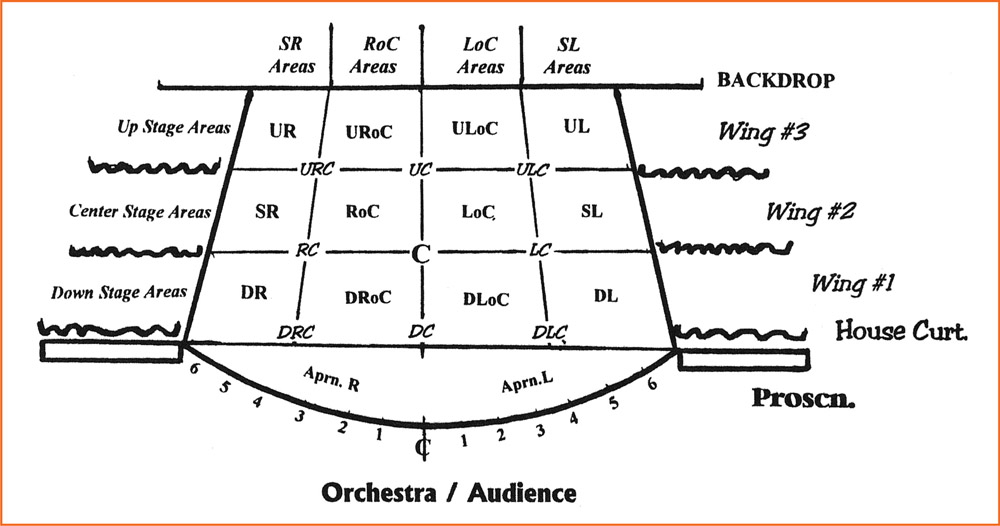

Greater Division of the Stage—Cutting the Stage Horizontally

The stage as it is divided thus far does not give enough reference points for the SM to take down detailed and accurate blocking. The stage needs to be divided in two more ways: first, horizontally, as in Figure 11-7. Note the areas now created on each side of the stage.

Cutting the Stage Vertically

Then in Figure 11-8, by vertically cutting the stage right side of the stage and by vertically cutting the left side of the stage, even more areas are now created that can be noted into the blocking script.

New Center Point

With cutting the stage horizontally and vertically, some new center points are created. See Figure 11-9.

Full-View Drawing—Blocking Areas and Center Points

There is no need to divide the stage any further. If perhaps what we have done so far seems a bit overwhelming, wait until you see Figure 11-10 with all areas and center points noted. The best test given to determine good blocking notes is when an SM, a director, or an actor can go back to the notes a day later or years later, read them, understand them, and re-create the blocking as originally directed.

Take Heart: The drawing in Figure 11-10 is one I had laid out on my worktable for a good five or six shows whenever I was in rehearsals notating blocking. Photocopy this drawing and slip it into one of those plastic sheet protectors with a three-hole side tab that enables you to put it at the beginning of your rehearsal/blocking script. Then have it there in front of you whenever you are noting blocking.

Figure 11-7

Greater horizontal division of the stage, breaking it down into smaller playing areas.

Figure 11-8

Greater vertical division of the stage, breaking it down into even smaller playing areas.

Figure 11-9

New center points created where the various dividing lines intersect.

Figure 11-10

The complete stage breakdown, with all its reference points and performing areas.

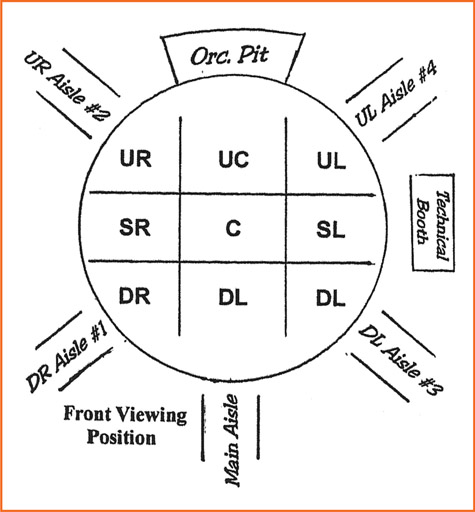

Arena Staging—Theatre in the Round

Just when an SM masters the art of proscenium blocking there comes a show that is performed in arena staging (be it a round or square stage), where the audience either surrounds the stage or is seated on three sides of the stage. The abbreviations and symbols for noting the blocking won’t change, but the reference points can at first appear less distinguishable until the SM gets some very specific and identifiable points and areas in mind.

First the SM must decide on a front viewing position of the stage, as if the audience was seated in a conventional theatre with a proscenium. This front viewing position can be based on a combination of things:

- The place in the house where the director sits most often to block the show

- The main entrance to the theatre

- A main aisle leading up to the stage

- The placement of the technical booth from which the lights and sound are run, and from where the SM calls the cues for the show

- For a musical, the placement of the orchestra pit

Having established a front viewing position of the stage, the SM has automatically established SR and SL and has created US and DS, and can now divide the stage into areas as with the proscenium stage (see Fig. 11-11).

Once the SM determines all the reference points to the particular theatre in which the show is performing, the SM can then draw out a stage floor plan using the same software program that was used for creating the floor plans in Chapter 6, “Hard Copy.” Then a copy of this stage floor plan can be slipped into one of those plastic sheet protectors with a three-hole side tab that enables it to be slipped into the blocking script when not being used and laid out on the worktable while noting blocking.

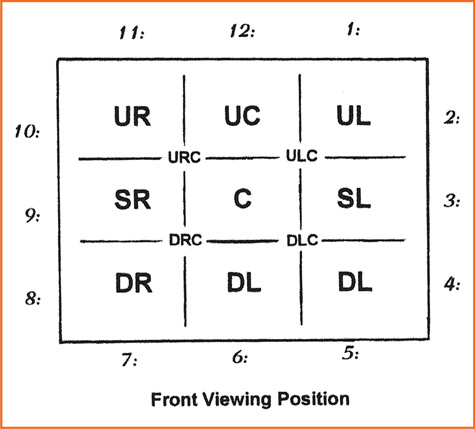

Arena Staging—Theatre in the Square

Should the SM be confronted with a square arena stage, there should be no difference. Once the front viewing position is established and all the parts surrounding the stage, such as the aisles, technical booth, orchestra pit, and so on, are named or numbered, then the performing areas on the stage are easily established.

Figure 11-11

Breaking down the circular arena stage into performing areas and using other points of reference to note blocking. Note that the aisles can be identified either by their stage position (DR, UR, etc.), by number (1, 2, etc.), or as demonstrated in the example (a combination of both the position and number). It is the SM’s choice, as long as everyone is working with the same information.

Also, whether in round or in the square, the SM might lay out the numbers of a clock, as in Figure 11-12. This breakdown alone is enough for the SM to make clear and detailed blocking notes. Using this around-the-clock method with an arena in the round is also possible, especially when the performer is directed to stand at the edge of the stage.

It can be very helpful to the actors, director, crew, and perhaps to the technical designers if the SM makes copies and hands out the breakdowns for either the round stage or the square stage. It puts the same picture in everyone’s mind and gets them using the same terms of reference.

Additional Areas and Abbreviations for Noting Blocking

In addition to the area breakdown of the stage floor, other parts of the stage can be used as reference points in noting the blocking:

- proscenium line = prosc.ln

- curtain line = curt.ln.

- show portals = ShwPort (R or L)

- wings #1, 2, 3, right or left stage = #1Wng R, etc.

- footlights, right, left, or center = Foots R, etc.

- dance numbers (at the edge of the stage) 1 through ? = dnc#1R, dnc#6L, etc.

- If in arena and using the clock numbers = @12:, @3:, etc.

With the addition of the scenery, set units, or big props like furniture, the SM has even greater reference points to use in taking down blocking.

Figure 11-12

The square arena stage with the numbers of a clock surrounding the stage to further aid the SM in noting blocking.

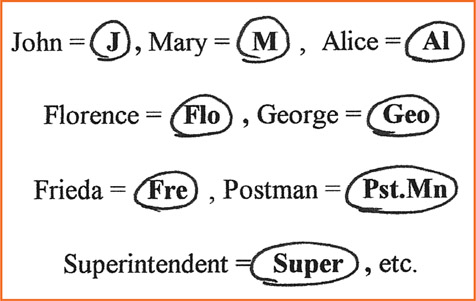

Abbreviations for Character Names

When having to note in the blocking script a character’s name, a good method of abbreviation is to shorten the name, even down to the initial if they are not easily confused with some other character’s name, and then circle it. Circling the abbreviation makes it immediately recognizable as a character. Figure 11-13 shows abbreviations for the names of the characters for our imaginary play, John and Mary.

Figure 11-13

Abbreviating the characters’ names and circling them for quick and easy identification.

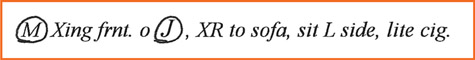

Noting the Actor’s Moves/Crosses

Whenever an actor moves from one part of the stage to the other, it is simply noted as:

- X = cross

- Xing = crossing

- Xes = crosses

Example of SM’s Blocking Notation in Shorthand

In our imaginary play John and Mary, the character Mary has been told to “Cross in front of John, go to stage right, sit on the left side of the sofa, take a cigarette from the coffee table and light it.” See Figure 11-14 to see how the SM noted Mary’s moves and stage business into the blocking script. Note the combination of abbreviations and symbols.

Figure 11-14

An example of how an SM might note blocking in shorthand.

Directional Arrows Speak Volumes

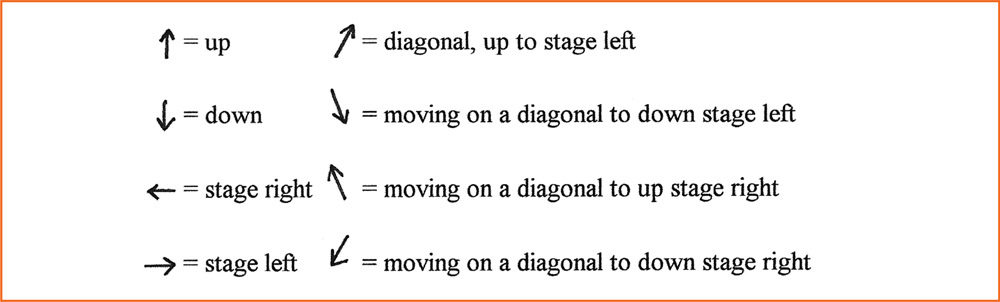

Here is a collection of arrows that say a lot with one symbol and stroke of the pencil. Arrows can be used to indicate direction as well as movement (see Fig. 11-15).

Another Blocking Notation Example

This is how the blocking note would be in long hand:

Intoxicated from drink, George stumbles up the stairs, tripping on the third step. When he gets to the top, he burps, smiles, and in his confusion, heads back down the stairs.

There is a lot happening here. Certainly it is too much for the SM to note while the direction was first being given, but also a bit too wordy even for the finished copy of the blocking script. So Figure 11-16 show how it would be noted.

It is not necessary to note the timing of the action. The actor will take care of that. However, should the director want a specific amount of time in any part of this action, then that too can be noted.

Greater Use of the Arrow

Figure 11-15

Arrows of direction an SM can use when noting blocking.

In the example above with George doing all that movement and business going up and down the stairs, the squiggly arrows shown in Figure 11-17 might have been more expressive and would have conveyed the inebriated state of George (note also the arched arrows).

Figure 11-16

The SM’s abbreviated words, arrows, and symbols to note blocking

Some General SM Abbreviations

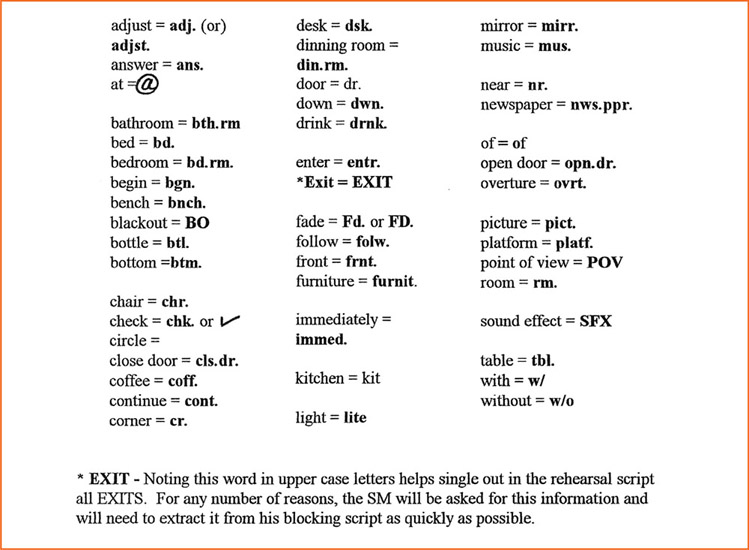

In writing blocking notes, the SM abbreviates words as much as possible. In doing so the SM follows no standard abbreviated form for the words written; the goal is to write as much detail as is needed in the smallest amount of space. The notes must be clear and understandable. Abbreviations must stand alone—they should not be mistaken or confused with another word. As an example, the abbreviation for bedroom and boardroom could be the same, Bd.rm. However, if the SM abbreviates boardroom as Brd.rm., there is no chance of it being mistaken for bedroom. Figure 11-18 demonstrates some typical abbreviations for noting blocking.

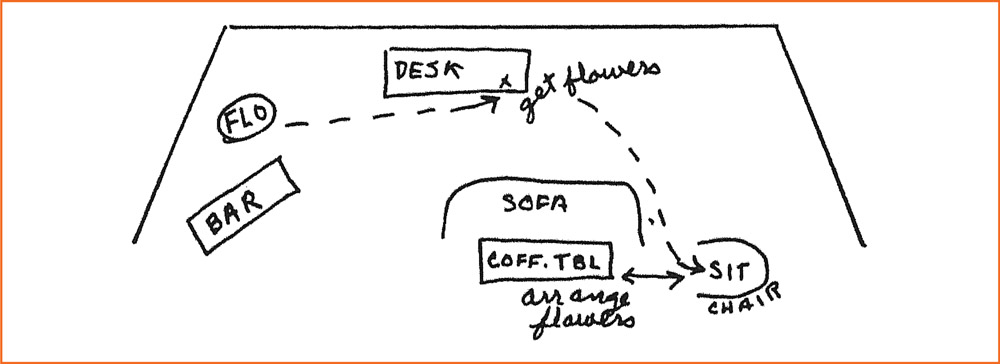

The SM’s Picture Drawing in Noting Blocking

The adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” holds very true for the SM when making blocking notes. However, the SM’s pictures or diagrams are very basic and primitive (see Fig. 11-19). They don’t need to be anything more, as long as they convey the blocking information. In this example, the character Flo, from behind the bar, crosses left over to the left corner of the desk, gets some flowers, crosses down to stage left, sits in the chair, and as we see from the two-headed arrow between the chair and the coffee table, arranges the flowers. While it took several lines of text to explain Flo’s action, movement, and stage business, the drawing in Figure 11-19 says it all.

Noting Blocking for Busy Scenes

Annie Get Your Gun Train Scene

There is a scene on a train in the musical Annie Get Your Gun that is confined to the space of a sleeper car with a double berth for sleeping. The scene involves the character Annie, three children, and four of the principal performers. There are times during this scene when all of the characters are on stage at the same time, and the blocking can be fast paced and played for as much comedy as the director and actors choose. It is the SM’s job to capture in the blocking notes the movement, the action, the stage business, and as much as possible the comic values of the scene. For the SM, this train scene is broken up into three parts:

Figure 11-17

Examples of squiggly and arched arrows and what they mean to further aid an SM in noting blocking.

Figure 11-18

A list of words and their abbreviations an SM might use in noting blocking.

Figure 11-19

A small, primitive diagram the SM might draw when noting the blocking of the character Florence from the imaginary play John and Mary.

- Annie’s entrance with Jake

- Buffalo Bill’s entrance with Charlie, which is shortly followed by Frank’s entrance

- Dolly’s entrance and encounter with Frank

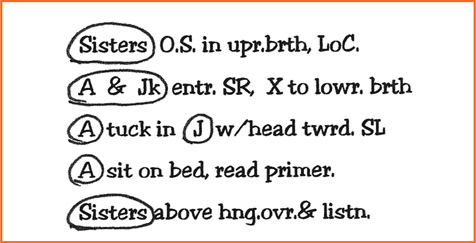

1. Annie’s Entrance with Jake

The long version of the blocking notes for this scene might be written as follows:

As the lights come up, Annie’s two sisters are already on stage, playing in the upper berth, which is placed left of center. Annie and her brother Jake enter stage right. They cross to the berth. Annie tucks Jake in the lower bed of the berth with his head going toward stage left. Annie then sits on the stage right corner of the bed, takes Jake’s primer-reader, and reads. The sisters hang over the edge of the upper berth to listen.

This is translated into SM’s shorthand, as shown in Figure 11-20.

Figure 11-20

The SM’s way of noting busy or complicated blocking for a train scene in the musical Annie Get Your Gun.

2. Buffalo Bill’s Entrance with Charlie, Shortly Followed by Frank’s Entrance

The longhand version:

As Annie reads, Buffalo Bill and the show manager, Charlie, enter from stage right. They stop stage right center to talk. They do not see Annie and she does not see them. Annie continues to read. Just as Buffalo Bill and Charlie get into place, Frank enters from stage left. He sees Buffalo Bill and Charlie. Not wanting them to see him, Frank does a comic circle around himself and starts to exit the same way he came in.

Figure 11-21

Continuing the same train scene from Annie Get Your Gun, with the SM’s blocking notes for the entrance of Buffalo Bill (BB), Charlie (Charl), and Frank (Fr).

The SM’s shorthand, abbreviations, and symbols in Figure 11-21 tell it all in a small block of text.

3. Dolly’s Entrance and Encounter with Frank

Just as Frank is leaving, Dolly enters left at the same time. They bump into each other, each spinning off the other, and end up going in the opposite direction in which they were heading. Thus Dolly exits back out the door and Frank heads straight for Buffalo Bill and Charlie.

While the longhand description for this section of blocking and comic stage business reads like a novel, the SM’s notes are concise, highly abbreviated, and to the point.

Figure 11-22

The same train scene from Annie Get Your Gun. The SM notes the blocking for the comic business between Frank (Fr) and Dolly (Dol).

The Absence of Some Blocking Details

Although the SM is required to be detailed in the blocking notes, they should not include things that actors bring to the part, such as feelings, emotions, attitude, gestures, or reactions, unless they have direct importance to the storyline or play in some way. If the SM does make these notes, it is for the SM’s information only, and when a director or an actor asks for blocking from the SM’s script, the SM does not deliver this additional information. The actors and director want only the basic blocking information—the moves, placement, stage business. They will fill in their parts. No SM, director, or anyone else for that matter should expect one actor to do what some other actor has done in the part previously. In the same light, the SM does not always note timing, such as the number of beats or seconds the actor takes in a dramatic pause, or the number of steps an actor takes to complete a movement or action, unless of course the information is important for comic value or dramatic effect to the scene or the play.

Neat Blocking Notes

It is very important for the SM to be neat in penmanship when noting the blocking. It must be clear, orderly, and highly comprehensible so the SM or anyone else can read it at a later time. There is no time for a quick scribble with the intention of going back to the script at a later time to rewrite the information, unless the SM wants to spend hours doing a task that could have been time for doing something else. Learn to be neat and clear on the spot while making the notations. Furthermore, the SM uses only pencil when making blocking notes. Change is certain—it is the rule and not the exception.

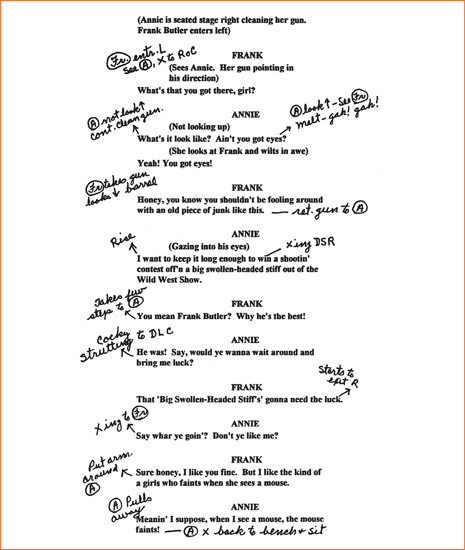

SM’s Blocking Notes as Written on the Script Page

The example in Figure 11-23 is an edited scene from the musical Annie Get Your Gun with the SM’s handwritten blocking notes. This is the scene where the scrubby and gawky Annie Oakley meets for the first time the handsome and egotistical Frank Butler. Take note of the detail in the blocking notes. Both the director and actors wanted the action done at specific times and on certain words.

The Numerical Way to Note Blocking

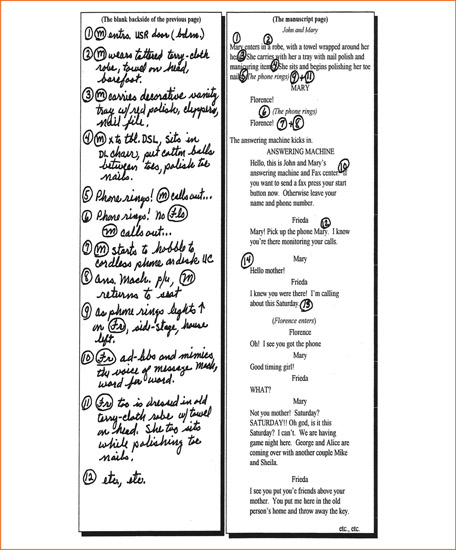

Sometimes when the blocking of a scene is intricate or complicated, or the interplay between characters is involved, or when there are a large number of people in the scene, the SM might want to use the numerical way of noting the blocking. With this method, the SM merely jots numbers on the page of dialogue where the blocking notes are to take place, and then on the blank page to the left (that is the backside of the previous page) writes out the notes.

Figure 11-24 shows Scene 1 from Act I of our imaginary play John and Mary—the scene in which Mary’s mother, Frieda, calls. The director chooses to have Frieda seen by the audience as she makes the call, rather than having her backstage talking over a mic. The director’s objective is to show how mother and daughter are so alike even if they seem to be at odds with each other when they speak. In noting the blocking for this scene, the SM is required to note in detail the actions of all the characters.

Note in Figure 11-24 the amount of numbers listed in the small paragraph of stage directions at the beginning of the scene. The numerical way of noting blocking has allowed the SM to make copious notes on seven different directions and their details. Note also that the numbers are not all in numerical order as you read down the page of dialogue. Notes 9 and 11 come before notes 6 and 7. This is because the director added these directions/details later in the rehearsal. When this happens, the SM just notes the numbers on the page of dialogue and then makes detailed notes on the page to the left. Later, perhaps in understudy rehearsals, the SM sees numbers 9 and 11 on the dialogue page and refers to the same numbers on the left-hand page.

The numerical approach, however, has its drawbacks. It is not recommended when working on a new play because there will likely be script changes. New pages will replace old ones, and when the old pages are removed, so are the blocking notes on the backsides of those pages. In a new show, if the SM chooses to note blocking using the numerical method, it is safer and wiser to insert blank pages to make the blocking notes.

A Tip and Invention: In the past when I have needed to use the numerical way of noting blocking, I have inserted a half or three-quarters page. This way the blocking notes on those extra pages did not become part of the overall pages of the script when I had to quickly flip through to find a particular page or scene.

Figure 11-23

The SM’s handwritten blocking notes for the first meeting scene between Annie Oakley and Frank Butler from the musical Annie Get Your Gun. ((c) 1949, 1952, 1967 by Herbert Fields, Dorothy Fields, and Irving Berlin. Copyright renewed. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used by permission.)

Figure 11-24

The SM’s numerical way of noting blocking. Numbers are placed on the dialogue page, while details of the blocking are noted on the blank page to the left (the backside of the previous page of dialogue).

Theoretically and Academically: In some schools of thought it is said that the SM should maintain and retain the old blocking notes that have been changed or are no longer in use, just in case the performer or director at some later time wants to go back to the old way. In theory this is ideal, but as a practice how is it done? First of all, the old blocking must be quickly erased to make room for the new blocking. So then how is the old blocking preserved? Remember, when noting blocking, the SM does not have time to transfer the old information to another place and at the same time keep up while the new blocking is being created. I have no answer for this and I guess, being delinquent in this area and perhaps as a lesser SM, I never attempted to keep the old blocking notes. Perhaps an instructor or some other SMs might have a way—if so, latch on to it and make it your own.

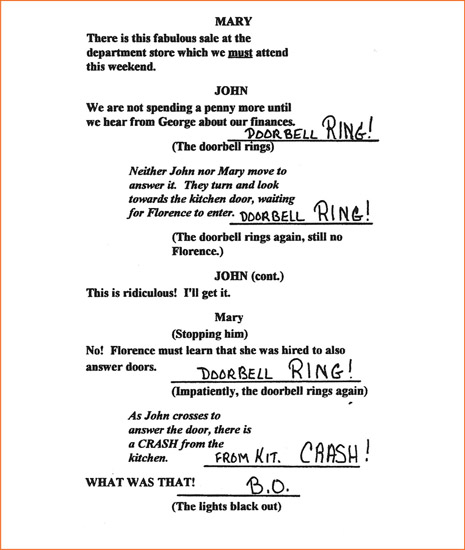

The Publisher’s Stage Directions and Technical Effects

Any manuscript, whether published or unpublished, has written into it stage directions that the author or some director has created. The script will also have noted into it technical effects inherent to the script. For the most part, directors read the stage directions once and then ignore them, doing as they choose. In the second or third reading of the play, the SM should write in pencil in the right margin all the effects that are cues in the show. Using our imaginary play John and Mary, Figure 11-25 shows how the SM’s script would look after the second or third reading.

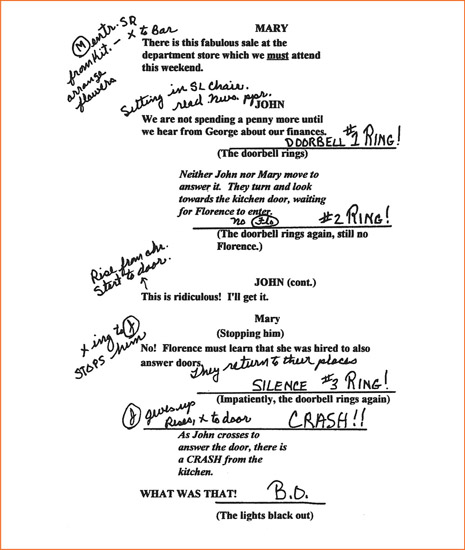

Some SMs prefer highlighting the technical effects that are printed on the page. This is a workable idea, but it becomes a wasted step. For two reasons, the SM should note these doorbell cues as they will eventually be noted in the cueing script—the script created and used for calling all the cues in the show during the performance, which we will discuss in detail in Chapter 13. The second reason being that the director will surely have some business happening before each ring, and that stage business will have to be written in so that during rehearsals, as the performers rehearse the scene, the SM will verbally call out the “rings” in the correct spot and moment. The rehearsal script will look something like Figure 11-26.

Organizing the Rehearsal/Blocking Script

Tabbing the Scenes

During rehearsals it is extremely helpful for the SM to tab the pages of the rehearsal/blocking script. The SM places the tabs at the beginning of each scene. When working on a show in which there will be script changes, it is wise for the SM to insert between each scene a card-stock page and attach the tab to that page. Then, when the changes are made, the SM can quickly remove the old pages and have the tabs remain in their proper place.

Inserting the SM’s Personal Floor Plans

In addition to tabbing each scene in the rehearsal/blocking script, the SM should insert a copy of the personal floor plan for that particular scene. On it the SM can note prop and furniture placement and the initial placement of the actors as they begin the scene.

Script Changes

Before computers and copying machines were readily available, the task of doing rewrites could be time consuming, requiring late hours after rehearsals. Script changing can be done in various ways, with varying numbers of people involved. Sometimes it is privately done between the director and writer. Other times the producer and assistant director are included. On occasion, the SM may be there, but mostly in a secretarial capacity.

First comes the creative session to make the changes. Then the task to get the rewrites entered into the computer, printed out, copied, and made ready for distribution for the next day’s rehearsal. The SM may be left to do this work alone or may be aided by the ASM or the PA. If the SM is really fortunate, the assistant director will take full responsibility for the entire matter and have the changes ready and distributed each time they are made.

The Electronic Script

There is some good news and some not so good news for the SM on this matter. The good news is that if the show is brand new and is being produced for the first time, the script will be available to the SM in an electronic file. Even better news, if the show is brand new, more than likely all script changes will be done by the writers and out of the SM’s realm of work. The changes will come the next day as hard copy. The SM can ask that an electronic copy of

Figure 11-25

An example from the imaginary play John and Mary of what the SM’s rehearsal script might look like going into rehearsals. The SM notes the technical cues inherent to the script. Later the SM will be more specific about their placement and when to call these cues.

Figure 11-26

The same scene as in Figure 11-25 after the director has blocked the scene. In addition to being specific about the placement of cues, the SM has now added the blocking notes to the script.

those script changes be sent as an attachment via email or put into Dropbox. The most popularly used program for writers of stage and movie scripts is Final Draft, so this becomes a program the SM must have installed on the laptop.

The not-so-good news is that should the SM be working with a script that has not been made into an electronic file and if the SM feels that it would be a great help to have this script on the laptop, then it seems the only way is to have someone company or some person type the entire script into Final Draft. Most assuredly that will be an expense most producers would prefer not to have, unless the SM can convince otherwise.

There are some programs that promise that each page can be scanned into their software… but SM beware! At the time of publication of this second edition, the process of getting the entire script into electronic form feels as if a college degree is needed. Then, to complicate things more, there is the difference between working on a PC and on a Mac, although at present Adobe Acrobat Reader is available to Mac users. It is, however, limited as to the SM’s needs, and the process is involved and requires quite a leaning curve.

For those working on a Mac, the news is a little better in that there is the Macintosh Highland App. While Acrobat Reader and the Highland App are good for getting the script into the computer, it appears that the script then still needs to be put into Final Draft.

This is about as detailed I can get on this matter without devoting a chapter to what the SM needs on the computer and the steps to be followed to get the script into a workable, editable, and usable form. Go on the Internet, or better still, network and talk with people who might already be fully immersed in working this way. It is hoped, by the time you are ready to be involved with this entire matter of getting an electronic copy of the script on to the laptop, some advancement will have been made and by the simple fact of scanning each page into the computer you can have a clean and workable script that requires no adjustments or transfer into another program.

Revised Pages

Some directors or production companies like to print out the new pages of the script in different colors for easy identification. This method is especially popular in films and television. It is not always necessary in theatre, depending on the extent of the rewrites. If the SM is responsible for making up the new pages, he or she should check to see what the director or production company prefers.

Marking Revised Pages

As each script change takes place, there should appear on each revised page, at the top right corner, a note identifying the page as a revision, just as the SM does with all charts, plots, plans, and lists when they are revised. The note should contain the word revised and the date. It is also a good idea for the SM to put a person’s initials following the date. This could be either the person who originated the change, such as the author or director, or it could be the SM’s initials: REVISED:(6-28-99)sj. This identifying mark becomes very important to ensure that everyone is working from the same script. It is the SM’s job to see that everyone who needs to have these changes receives them. Also, putting the revision information in a bright red or bright blue brings further notice that this is a revision page.

Script Changes That Create Extra Pages

Should a script change create extra pages to the overall script, in no way should an effort be made to change all the following page numbers! Simply “letter” those extra pages (a, b, c, etc.). If by chance the script change has fewer pages than what was originally noted, on the page that starts the original numbering make a note at the top of that page reminding yourself that the missing page numbers were a result of a script change.

Keeping Script Changes in Electronic File and Hard Copy

It goes without saying that whenever possible the SM keeps the script changes electronically, but also that extra hard copies are kept for on-the-spot distribution.

If the show has a lot of script changes, more than likely the individuals making the script changes have done them on their computers and have the changes on file. It is the wise SM who also keeps a good filing system on the changes. It is a good idea to make separate folders, one marked Current Script Changes, another marked Last Script Changes, and a third, Past Script Changes. Then as the changes take place, the changes that are already in file are shifted over to their next folder, and the newest changes are put into the Current Script Changes file. With this system in place, the SM is now armed and ready when, in the rehearsal room, the director asks to see the script change made two weeks ago and can provide that information without hesitation. This system can also be part of the SM’s folder files on script changes.

Following Script

Prompting, being on book, cueing the actors, following script—these are all terms that describe another important job the SM must do to keep the rehearsals running smoothly and efficiently. Both the director and actors expect one of the SMs to be on book at all times when they are rehearsing. When scenes are being blocked for the first time, everyone has scripts in hand, reading their dialogue and jotting down their blocking as it is created. However, once the blocking has been set and the actors are somewhat confident about knowing their lines and blocking, they will go off book and expect the SM to be on book, following script, and feeding them a line or piece of blocking should they forget.

Following Script for the Director

In following script, the SM must first serve and please the director. The director expects the SM to be ever present and ready, following the script line by line, moment for moment. The director does not want rehearsal time lost while the SM looks in the script for the line an actor has forgotten, nor does the director want to wait while the SM tries to decipher blocking notes. In some extreme cases, the director requires the actors to say every word as written in the script and do the blocking exactly as set, and expects the SM to correct the actors if they are the least bit off. This is a tedious task and not the most pleasant way to work, but if the director is important and very successful, then he or she can do as he or she pleases, and the SM works in whatever way chosen. For the most part, most directors allow greater latitude in this area, but nonetheless expect the SM to correct the actors if they go too far astray.

Following Script for the Actors

Following script for the actors can sometimes be a challenge. It is the SM’s job to be on script, ready to feed an actor a line or recite a piece of the blocking. Most actors, when they forget, are very good in asking the SM, “Line, please?” There are some, however, who stumble and grope, trying to jog their memory, or become silent as they search internally. Sometimes these actors want help from the SM but for whatever reason do not ask. This can leave the SM uncertain, because actors in rehearsal will also grope, stumble, or become silent when they are in a moment of discovery, or taking a dramatic pause. If the SM decides the actor has forgotten the line and delivers it, and if indeed the actor was in a dramatic moment, the actor can become very upset, first because the moment was broken and possibly lost, and, second, because with the delivery of the line from the SM, it appeared that the actor did not know the dialogue.

To avoid this uncertainty and to prevent the wrath of an actor who might be misunderstood, the SM tells the cast and director that he or she will feed lines and give blocking only when asked, “Line, please?” or “What is my blocking here?” It helps if the SM briefly explains why it is best to work in this way so the actors and director understand and are willing to make this part of their way of working.

Calling Out Lines

In calling out a line, the SM gives only the first part of the line. Sometimes only the first two or three words are necessary—just enough information to jog the actor’s memory. The actors know their lines, and usually hearing the first few words is all they need. For the SM to give more usually is an intrusion and becomes an annoyance. In addition, the SM simply reads the words from the page and does not deliver them with any sort of acting or interpretation.

Calling Technical Cues in Rehearsals

When following a script that has written into it technical effects with a direct effect on the scene or the actor’s timing, it is the SM’s job in rehearsals to call out such cues each time the scene is rehearsed. Calling out technical effects such as lightning, a doorbell, a telephone, a loud noise, a gun being fired, or scenery being moved during the scene aids the actors during rehearsals, giving them a greater sense of being in a performance. To call out technical cues that don’t have a direct effect on the moment being rehearsed is a distraction, an intrusion, and annoying!

The SM’s Delivery Technique

In the delivery of technical cues or special effects, the SM vocally interjects them at the correct time, saying, “The telephone rings,” or “Lightning,” or says in a clear and audible voice, “The gun is fired.” The SM may choose to imitate some sound-effect cues. This is acceptable as long as it is not laughable or distracting. If, according to the script, the gun is fired unexpectedly, the SM might call out in an explosive manner, “Bang!” maybe even slamming a hand on the worktable to enhance the effect and perhaps jar the actor. There are, however, some things better said than imitated. It is enough to say, “The car starts” or “Footsteps are heard approaching.”

When having to give an action with some detail, the SM needs to keep it simple and to the point, choosing adjectives that best fit the action and mood:

- “The car starts with a ‘choke’ and ‘gasp,’ followed by a puff of black smoke.”

- “The rain starts falling gently on the roof.”

- “The sound of footsteps of a woman wearing high heels is heard coming down the hall—stopping from time to time as the steps draw near.”

Sometimes, before the scene begins, it helps to set the mood and get the scene started if the SM is a little more poetic in this presentation:

- “As the curtain rises, brilliant sunlight beams through the downstage window, and the song of morning birds fills the air.”

- “As the lights in the room fade to black, we hear footsteps approaching. Suddenly they stop! In a burst, the door swings open. There silhouetted against the hall light is the slight figure of a little man. The curtain slowly comes in.”

Each SM develops his or her own approach in following script, giving lines, and calling out technical cues. The SM who is selective and keeps it simple will be highly successful and become even more valued as an SM.

Timing Scenes, Acts, and the Whole Show

Throughout the rehearsal period, the SM will need to time some or all parts of the show. Some directors are greatly concerned with the length of scenes and ultimately the whole show. Some directors will from the very first reading ask the SM to take a timing. Certainly, once a scene is blocked, the SM should periodically take timings. This is particularly important with a new show. With each timing, the SM notes the results on the rehearsal script at the beginning of the scene, in the left-hand margin, along with the date of the particular timing. This information is then readily available for the director, and comparisons can be made with other timings.

Props

Props, too, hold an important place in the SM’s job during rehearsals. Props, which include hand props and furniture, require the same intensity of attention as the other parts of the SM’s work. Of all the technical departments, the SM is most involved and most knowledgeable of the props used in the show. The SM is there in the rehearsal hall when they are introduced into the play and starts the prop list from the first readings of the play. The SM knows their placement, and each day in rehearsals (if there is no prop person working the rehearsals) sees that the props are set for each scene being rehearsed.

With a brand-new show or a heavy prop show, the head prop person is often hired to start working at the rehearsal hall on the first day of rehearsals. With some shows, producers are able to hold off until the last week at the rehearsal hall. Fortunately, in many regional theatres, the property master is hired and on staff so he or she is available from the start and after an initial meeting can be in communication daily via the daily report, text, or email.

Detailing the Props

With the SM being the key person in creating the prop list, it is important that the SM be organized, specific, and detailed. During rehearsals as each prop is introduced into the show, the SM needs to observe and seek out from the director and actors what they want, what they need, how the prop is used, whether it needs to be real or can be fake, and then convey that information verbally and on a list to the person gathering the props.

Red-Flag Props

As each prop is introduced into the show, it is important for the SM to visualize the prop and think around it. That is, the SM not only sees the prop mentally, but also sees other props that might be generated because of this one prop. Neither the director nor actors will think of these additional or secondary props until they get on the stage with the real prop. It is the SM’s job to think ahead and add the secondary props to the prop list. For example, if the actor in the rehearsal is told by the director that the character lights up a cigarette, a red flag must go up in the SM’s mind. Smoking a cigarette on stage means more than noting cigarettes on the prop list; even with an electronic cigarette the illusion must be kept by having matches and an ashtray. Should the cigarette be real, a slight amount of water should lie in the ashtray to ensure the cigarette is fully put out. As a consideration, the SM might also ask the actor if a particular brand of cigarettes is preferred. Also, know that more and more real cigarettes are being banned. So as soon as a cigarette is mentioned, the red flag should be raised. Certainly the prop person should know, but it is the thorough SM who seeks out the information for sure.

Red-flag props are props that generate other props. As soon as food or any perishables are mentioned in rehearsals, a giant red flag should go up in the SM’s mind. Food items require the SM to think around the item in great detail:

- Is the food real, fake, or a substitute for the real thing?

- Do the actors eat the food?

- Do any of the performers eating or coming in contact with the food have allergies?

- Can the food be easily eaten during the performance so the actor can continue to speak or sing?

- Are dishes and/or utensils, napkins, or towels needed?

- Is the food perishable? If so, is a refrigerator needed?

- Does the food need to be cooked or prepared in some way?

- How much food is needed for each performance?

- What cleanup items are necessary?

The Metamorphosis of the Prop List

▸ Stage 1: The list begins with the SM’s first readings of the play as the SM enters into the laptop the props inherent to the scene. Some of these will be specifically mentioned; others will be noted through the dialogue or action. Included on this list are also set dressing props—items that need to be on the stage, but are not handled or used by the actors, props that have been specified in the author’s notes or have come out of the dialogue. From this list, and in talking with the director, the SM creates a rehearsal prop list for the person who will be procuring the rehearsal props.

▸ Stage 2: This next stage starts once the rehearsals begin. During this stage, the SM’s list grows daily in size and detail. As the director and performers rehearse, the SM might handwrite the prop notes and later enter them into the computer in the prop file.

▸ Stage 3: This begins with the different meetings the SM will have with the person procuring the props, be it the prop person working the show or the person just purchasing the props. During these meetings the SM provides a clean, organized, and detailed list, noting the specific needs and descriptions of the props. The list grows as the director and actors work on the show, and the information is given to the prop person at the next meeting or more conveniently sent electronically. Providing this information as it grows in bits and pieces is the only way the SM and the prop person can work and still be ready for the first day of technical rehearsals at the theatre.

▸ Stage 4: This is the final stage of the prop list—the Performance-Preset Prop List. Toward the end of the rehearsal period, no later than the last week, the SM puts together this show prop list from which the prop person and the SM will work. Look back to Figure 6-20. Notice that on this list the information describing the props and how they are used has been eliminated. Also, the props are no longer listed within their scenes but rather in how they are set at the top of the show. From this point, the prop list remains the same in form. The only changes made will be whatever props the director, actors, or designers add or take away.

The Performance-Preset Prop List

The props listed on the performance-preset prop list are listed according to their placement backstage and on stage, before the performance begins. This enables the SM to check the preset placement of all props. The SM can start in one area, let’s say the backstage on stage right, and then work toward the stage right wings, on to the stage, across the stage, into the stage left wings, and into the backstage areas on stage left, checking all along the way the placement of the props. The creation of the performance-preset prop list usually is assigned to the ASM, whose job it is to check the props for each performance after the prop person has finished setting them.

In Closing

During rehearsals, as well as throughout the production, the SM must be careful not to get into the position of doing work that is not part of the job, especially work that takes the SM away from the rehearsal hall. The rehearsal period is the center of action, change, development, and growth. As much as possible the SM needs to be at that center.

Each SM’s experience of rehearsals will be unique, depending on the show and the people working on it. Throughout the rehearsal period the SM must be focused and concentrated on all parts of the production. It is the SM’s job to oversee, observe, and keep the rehearsals running smoothly. In addition, the SM must note the blocking for the show in the rehearsal script, keeping it updated along with all charts, plots, plans, and lists. The SM must keep the lines of communication open to all departments, seeing that all changes are properly noted and distributed. While doing all of this, the SM is also thinking ahead or reflecting back, anticipating problems or heading them off. If the SM falls short in any one area and things go wrong, people will be quick to place blame. Whenever possible, the buck and the blame stop at the SM’s desk!

There is still more to the rehearsal period at the rehearsal hall—the last part of rehearsal, the closing part. Primarily, this part takes place in the last week of rehearsals at the rehearsal hall. In a rehearsal period of seven or ten days, this last part will be in the last two or three days. The things that happen in the last week or last few days include information enough for another chapter. So without further delay, turn to the next chapter and let’s see what things need to be done to close out the rehearsal period.