17

Run of the Show

It is now the day after the opening performance. The show last night went exceptionally well for everyone. From the audience’s reception, the show is a hit. However, the first reviews in the morning papers were mixed and not encouraging. The producers have faith in the show. The publicity campaign is strong and they know that word of mouth will sell the show. Already, ticket sales are up at the box office.

Reviews and Ticket Sales

Regardless of how good or bad the reviews, how great or poor the ticket sales, the SM’s work remains the same. These things have no bearing on the work the SM does during the run of the show. In talking to the cast over the PA or in meetings, the SM does not deal in terms of ticket sales or reviews. In fact, the SM does not need to post reviews on the callboard. There is always someone in the cast who follows reviews and ticket sales and brings that news to the company. If the cast chooses, they may post a review on the section of the callboard set aside for them and their social business. The impact of negative reviews or poor ticket sales that are demoralizing and destructive to the cast and show can be greater than that of good reviews or sold-out performances that boost the morale of the company and make the show better.

A New Show

If the show is new and is perhaps heading to Broadway, a wave of intensive work still lies ahead. The workday will become a double-duty event with a rehearsal and changes made in the afternoon and a performance at night. There will be eight performances a week, performed on six consecutive days, with the seventh day being the day off. This means that two of the performance days will have matinee performances in addition to the evening performances. This sort of schedule for a workweek is carefully guided and ruled by Equity, with time frames for rehearsing, breaks, and performances. The SM must know the breakdowns and particulars of these rules, schedule things accordingly, and see that the producer and director follow the guidelines, or they will have to pay overtime or penalty fees.

Also, if the show is heading to Broadway, it more than likely will be playing out of town, perhaps playing in different cities. Touring a show adds still another layer of work for everyone. We’ll talk more about touring shows in the next chapter. If the show is the revival of a play that has been previously produced for Broadway and plans to play only in one place, there may be rehearsals for a few more days, after which the show is left to play out its run.

A Shift in Work

Whether performing on Broadway or in just one city, once the show gets into its run, rehearsing stops, and there will be no more changes, the show is considered frozen—that is, the show is now to be performed each time as set and agreed on by the director, actors, and producer. The director leaves and the producer’s attention goes to selling and promoting the show or to another project. It is at this point that one of the first things an SM does is to make a copy of the cueing script. With color copying machines now the standard, this is easily done. There are computer programs in which a cueing script can be created, but when doing a musical, oftentimes the features and abilities of those programs are not sophisticated enough to note what the SM needs to call the show efficiently and with perfect timing. Until such time, the cueing script will remain handwritten and a copy must be made, safely tucked away, and probably in some place other than theatre.

Company Manager and SM Left in Charge

If there is a company manager with the show, the SM and company manager take over, running the show and the company. For the most part, the company manager runs the business of the company, being concerned with the daily finances, overall budget, and administration of the company. The SM takes full charge, maintaining the performance level and artistic integrity, and generally caring for the members of the company, seeing that their needs are met and their problems resolved. With the absence of a company manager, the production office handles most of the company manager’s work with the SM aiding and assisting.

If the show is an easy one and the company is cohesive, performing well together, and maybe behaving like an extended family, on most days the SM’s work can be easy. It can be as simple as going to the theatre, performing the show, having some social time with the cast and crew after the show, and going home. With a musical, a show that is technically involved, or a large cast or a cast that is problematic, the SM’s days can be filled with the business of the show and continue to be long.

The SM’s Work and Responsibilities

Whatever the working situation of the show or the company, there are some very specific things an SM must do as the person in charge while the show is in its run. These duties are clearly defined:

- Calling cues for each performance: We have discussed at length how important it is for the SM to call an impeccably well-timed show for each performance.

- Keeping the show at performance level: This subject too has been frequently brought up in various parts of our conversations. In short, the SM sees that the show continues to perform with the same integrity and intention as created by the combined efforts of the actors, director, producer, creators, and designers. This means keeping a watchful eye on the level of performance and changes the performers make to the show, and deciding if the changes are an enhancement or detraction.

-

Caring for the company: In many ways the SM has already been performing this job. Now the SM has full responsibility and is the person to whom the company members turn with their problems, concerns, suggestions, and so on. It is the SM’s job to handle as many matters as possible, or point the company member in the right direction to resolve a problem the SM can’t handle. The decisions the SM makes, the advice the SM gives, or the directions the SM expresses in leading and guiding the company are on behalf of the producer and the director. By this time, the SM should know the producer and director well enough to formulate and adjudicate as they would. If the SM is uncertain on a particular matter, a conference with the producer and director is appropriate to get their input. The SM also uses Equity and the Equity rules as an aid. This is another time when it is important the SM be a scholar and aficionado of the Equity Rulebook and work closely with the Equity deputies.

As part of the SM’s caring for the company, the SM tries to anticipate problems and head them off, or see that adverse situations and conflicts do not escalate and become blown out of proportion. In addition, now that the SM has established a way of working and what is professionally expected from everyone, the SM can encourage and support small activities and little events that are fun, do not hurt the show, do not detract from the performances, and at the same time bring the company closer together in bond and relationship.

- Keeping the producer and director appraised and informed: Depending on the working situation and what is set up between the producer and director, the SM may be in communication with the producer and director daily or on a need-to-know basis. All behavioral problems are to be handled by the SM. The only time the producer wants to be brought in is when the problems may have a direct effect on the show or hurt the producer’s pocketbook in some way. The director’s primary interest is in the artistic integrity of the show, and although the director may lend a sympathetic ear to the SM who must work with a problematic cast or company, the director is glad to be removed from the problems and have the SM keep full responsibility.

- Keeping a logbook or journal: If the SM has not started the SM’s logbook from the start of rehearsals, this process definitely needs to start now. While some SMs choose to start a logbook account from the first day of rehearsals, it should start no later than the dress rehearsals and preview performance and continue on through the entire run. The SM notes the running time of each performance, pertinent or important business of the day having to do with the show and company, all events that are unscheduled or unexpected, the audience’s reaction and reception to the performance, the behavior of the company members, and, when a problem is approaching or in full bloom, any observations about the problem as well as what is being done to head off the problem or has been done to resolve it. If desired, the SM can also make personal commentary. More on the subject of the logbook in a moment.

- Understudy rehearsals and actor replacements: It is the SM’s job to have the understudies prepared and ready to perform at a moment’s notice. If the show has standby performers, the SM keeps them up on their roles. If the show requires replacement performers, it is the SM’s job to do so whenever the producer or director dictates.

The SM’s Logbook

We have briefly touched upon the importance of the SM’s logbook in Chapter 5, “The Electronic SM”:

Much of what was written in the logbook is now part of the daily report and, when the show is in performance, the running time chart; however, in my opinion, there are “personal” items that are not for general publication. The logbook is where this information is noted. These items are noted and reported in a journalistic fashion, without opinion or bias. Then, in a closing paragraph, the SM makes comment, gives opinion, expresses feelings, and writes down observation. The producer or director may be privy to the contents but no one else, unless the information is needed by Equity about one of its members, in a dispute between the employer and employee, or in a court of law as evidenced by the story at the end of Chapter 5, “Logbook, the Star Witness.”

So it is my recommendation that the SM keep on the computer an “electronic logbook” in which such information can be noted and be given only to the right people upon request. The entries need to be noted with clarity—information should be detailed but concise, factual, and truthful. The SM must be careful to note the information in an unbiased and journalistic way, more as a historian. If at any time the SM chooses to express a professional opinion, experience, observations, suggestions, or judgments, or chooses to editorialize, this should be clearly noted in the log.

In being thorough and in documenting the production, the SM might start this private electronic logbook in the pre-production time before rehearsals begin. Other SMs will start it with the first dress rehearsals and into the run of the show. If the SM starts the logbook during the rehearsals, it is not necessary to note the schedule—that is documented in the daily schedule and a copy is kept in the SM’s files for reference.

During performances the SM keeps a notepad on the console just under the cueing script, ready to slip it out to make notes. The SM will note the starting times and ending times of each act and calculate the running time of the whole performance; make notes on performances that are exceptionally good or not up to par; comment on audience reactions, encore curtain bows, and standing ovations, if any; and note lost lines or dialogue, cues missed, mistakes made, mistakes almost made, and incidents or near incidents. The SM notes joyous times, sad times, noise backstage if it becomes excessive, late entrances or near-late entrances, infractions of rules, shoddy work, conflicts and confrontations, unprofessional behavior, or anything that could be used as a reference for a later date. Seemingly small and unimportant notes written in today’s entry can become tomorrow’s valuable information.

After the performance, the SM transcribes these notes into the electronic logbook and then copies and duplicates some of that information that is suitable and appropriate for the daily report and the performance running-time sheet. When the run of the show ends and the show closes, the electronic logbook entries remain on file with the SM. It does not go to the producer along with the final production book.

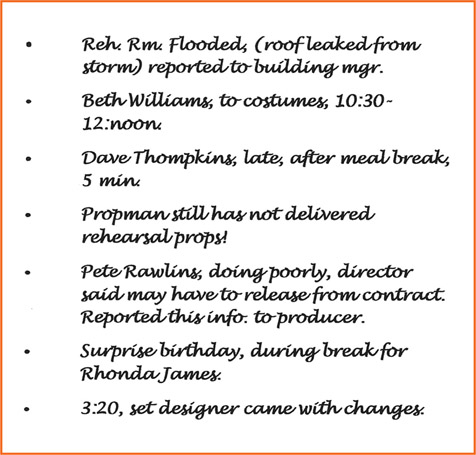

Sample Entries in a Logbook

Figure 17-1

A partial list of what the SM entered into the logbook on a particular day.

A More Complete Example from an SM’s Logbook

The following example is an actual account of a show produced in Los Angeles. It was a musical production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The logbook was originally handwritten by the SM in a blank-page hard-bound book. However, the version presented here has been edited and re-created, singling out days that were particularly interesting, and displays some of the things an SM might write.

The original logbook contained names and personal information that was not meant for publication. The show starred several prominent performers of the Hollywood and Broadway communities. The seven dwarfs were played by real dwarfs who instructed everyone to call them “little people.” This show was targeted at adults as well as children and was planned to play throughout the spring season for the Easter holiday and spring vacation.

As you read the SM’s entries for this particular show, keep in mind that this was an exceptionally problematic situation, due mostly to the producer and his behavior. In most other shows, the SM’s log entries are pedestrian and not filled with so much conflict and drama.

Also, because of the problems with the producer, and with the SM realizing that this book can be considered a legal document and called for in arbitration or a court of law, the SM is careful to put in all the archival information necessary to document names, times, and places.

▸ Stg.Mgr’s LOGBOOK, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (A Musical Stage Version)

Beverly-Wilshire Theatre—Spring Break/Easter Vacation, Los Angeles, CA,

March–April 2008

Producer:

Director:

PSM: Sarah Johnstone, ASM: Dan Porter

Star Performers:

Cast Members:

▸ Saturday, Mar. 23, 2008 First day of rehearsals, onstage, at the Beverly-Wilshire Theatre.

10:00 am, Equity business: WHAT A MESS!!! Producer’s office did not have contracts ready. Equity field rep refused to let rehearsals begin without contracts being signed. Finished Equity business 11:00 am (extra hour becomes part of producer’s rehearsal time).

12:00–3:00 pm: Little people sent on a three-hour meal break.

End of Day: Producer wants to keep performers past 6:30 pm (past eight and a half consecutive hours) without paying overtime. He complains the Equity business robbed him of an hour rehearsal time. I pointed out the use of the extra hour for Equity business was due to his office not having contracts ready. He retorted that Equity could have bent the rules and let him rehearse today and he would have had the contracts ready on Monday. He also suggested that the little people could remain and rehearse because they had a three-hour meal break. Again I had to explain that was his choice and that he could not break up the performers’ day. They were still on call after the first hour and a half of their break. Reluctantly, he let everyone go home at 6:30 pm.

▸ SM’s Commentary: Producer seems to blame Equity for his bad day, and because I am aligned with Equity and make him stick to the rules, he seems to pass the blame on to me too. In the short time I have been dealing with this producer, I feel disaster coming. This producer is a “wheeler-dealer.” Always looking to break the rules—get a special deal. Money comes above any other consideration. Experience has taught me to look out for bad checks from this guy.

▸ Monday, Mar. 25, 2008 Good day today. Schedule followed, much accomplished. First time principal performers worked together. Good Ensemble feeling. FUN! Director, too, good mood. Pleasant. Not so nervous or angry.

▸ Wednesday, Mar. 27, 2008 11:15 am: Producer walks in w/CBS news crew—NO NOTICE!!!! Performers upset. Want time to fix hair, put on makeup. Checked Equity Rulebook—24 hrs. notice for press/publicity required. Equity deputy called Equity office. They said to go ahead, and they will settle matter with producer.

Today was little people’s day off. Producer called each of them personally, last night, and asked them to come in to rehearse—to VOLUNTEER their time. Four showed up: Terri Rivers, Jack Hammer, Andrea Neville, Jane Roberts. Equity deputy reprimanded the four who came in and handled the matter with Equity. SM informed producer of Equity’s disapproval in this matter and will be talking to him soon.

Marie Lee, late (5 min.) this morning. This is her second time, but I don’t think she has a problem in this area.

After cast is dismissed we had a Production Meeting—7:30pm, Beverly Hotel: Chaotic and disorderly. Could not keep producer on one subject long enough to complete things. Designers and technical dept. heads not getting money from producer or checks are bouncing. Producer says money people back east shifted funds, left Snow White account dry. He assures matter will be resolved by Friday so checks will be here in LA next Monday.

▸ Personal Note: Today I overheard the producer on the phone backstage talking to his wife: “I can’t fire her. I’ll have to give her two weeks’ pay and where do I get another stage manager? We open next week.” After he got off the phone he approached me and accused me of going to Equity about his rule infractions (it was in fact the deputy and some of the performers, but I did not tell him that). I assured him I had not yet been to Equity on any matter, but used this opportunity to state my position and responsibility to Equity. He became angry. He told me that he was paying my salary and that all the stage managers he worked with back in New York showed their allegiance to the person who was writing the checks.

▸ Thursday, April 4, 2008 Two shows today:

11:00 am–12:15 pm: Entire cast called in to put the horse in more scenes. Horse is getting great reaction from the audience. Producer wants the horse to appear more in show.

Entrances changed for the little people in 3rd scn. Choreographer took the remaining time to clean dance moves.

NO BREAK for performers between rehearsals and half-hour for Show #1: Producer was made aware of OVERTIME and PENALTY to be paid.

Producer happy today. Show got good notices and we are playing to 95 percent capacity audience.

▸ SHOW #1

Act I, 2:08–2:45 = 37 min.

Intermission: 18 min.

Act II, 3:03–3:38 = 35 min.

Terrible audience—kids threw things onto stage.

▸ SHOW #2

Act I, 4:19–4:56 = 37 min.

Intermission: 22 min.

Act II, 5:18–5:53 = 35 min.

A good performance. Audience reaction great. Horse stealing scenes.

▸ MORE OVERTIME to be paid for end of day (see report turned in to Equity and copy to producer). Sheila Fuerst paged me. Check for star’s (witch’s) nails BOUNCED!

▸ Saturday, April 6, 2008

THREE SHOWS TODAY!!

▸ SHOW #1:

Half-hour call, 1:15

Act I, 1:49–2:25 = 36 min.

Intermission: 16 min.

Act II, 2:41–3:16 = 35 min.

Our star forgot to bring on stage her witch’s comb. Prop man was not there to remind her to pick it up from the prop table. Actress ad-libbed lines about returning to her castle to get it. Actress disappeared from view, got comb from prop man who was now standing in the wings, and reappeared within a second. Actress ad-libbed about what a tiring journey it was. Got great laugh. Audience applauded, actress continued to ad-lib few more lines.

Light board operator executed Q16 late. Was an obvious mistake to audience.

SM missed calling Q38. Audience was not aware but broke actor’s concentration.

Final curtain nearly hit Snow White again! She was told several times to step back after her bow—fast curtain coming in! I placed white spike mark where she should stand. If she misses mark again, I asked Prince Charming to step forward and lead her back.

▸ SHOW #2:

So that the producer would not have to pay overtime, the producer took out the intermission. (Show works better w/o intermission. Producer still able to sell merchandise before and after.)

Acts I & II, 4:20–5:30 = 1 hr. 10 min.

Dinner Break 5:30–6:30

▸ SHOW #3

Half-hour call for 6:30 pm

Acts I & II, 7:15–8:25 = 1 hr. 10 min.

Show started late due to latecomers. Traffic and parking problems. Excellent performance. Actors had fun w/show and so did audience.

This example is to show the type of information an SM might enter in the logbook. There is no particular form to follow. The SM must, however, keep in mind that once the information is written, this book is used for reference. With this in mind, the SM groups and separates the information for easy extraction. Sometimes key words or phrases will be in uppercase letters or made bold to draw attention.

Our discussions in parts of this book have talked of no more than two performances in a day. With this production of Snow White, on some days there were three performances. The difference had been worked out and agreed on between Equity and the producer. More than likely, Equity took into consideration the short playing time of the show as well as the number of hours the actors would be putting in for the day, and then made adjustments that were equitable to both the producer and the actors.

Actors Making Changes and Improvements in the Show

One would think with all the work done in rehearsals and the changes made in techs, this subject of making changes would be exhausted, but there remains still one more installment: the changes the actors bring to the show once they get into the run. These changes are sometimes jokingly referred to as improvements, and the SM, in trying to maintain the director’s work and intention, might say to the cast, “Take out the improvements.”

First there are the changes actors make as they grow in their parts, fine-tuning, working moments, perfecting timing, filling in characters with color, finding more depth and meaning, enhancing and making things richer. In short, the actors are taking wing and soaring in their parts. This can be exciting for the SM to watch as the characters mature.

The next part of change does not always come out of growth and development but rather in a search for perfection—to improve on the improvements. This often comes from the performers trying to make the parts new and exciting for themselves as well as for the audience. These kinds of changes can be borderline and sometimes questionable. The SM must make a judgment and get the actors to return to what is more acceptable if the changes are determined to be unacceptable. If the SM is uncertain about a change an actor makes, the SM may want to talk first with the actor, expressing any feelings, opinions, or concerns. If the actor feels the change is valid and is unwilling to change back, and it remains questionable in the SM’s mind, the SM then needs the advice and consent of the director.

The SM Knowing Acting and Directing

For the SM to do this part of the job well, it is helpful to have worked closely with the director and actors during the rehearsal period, watching the show come together and the characters develop. The SM also must be intimately familiar with the script—the plot, action, and storyline—and needs to know the director’s intent, interpretation, and direction. In addition to all of this, it is extremely helpful if the SM has a working knowledge of directing and acting. The more the SM knows in this area, the better the SM can make judgments, maintain what the director wants, and communicate and work with the actors.

Giving Actors Performance Notes

With changes the performers make comes another part of the SM’s job—giving acting notes. Even when a change is good, the SM should comment, expressing pleasure and approval. Now that the director is gone, it is an established fact that the SM will take over in monitoring the show, watching the acting and maintaining the director’s work, but the cast needs to be reminded of this.

For the SM, giving actors notes can be like stepping from the frying pan into the fire, walking a minefield, or simply stepping out from the trenches in the thick of battle. Getting notes on their performance is a highly personal thing for actors. For actors to do a good job, they personalize and draw from within themselves. To have someone make comment on their work can set off any number of reactions, some of which can be protective, defensive, guarded, angry, and possibly filled with ego. Up to this point in the production, the director has been the only person licensed to enter this arena. For the SM to be accepted, the SM needs to display knowledge in this area. The SM must also be guarded in the approach to performance notes. If the actor feels the SM knows what he or she is talking about, the actor willingly and openly accepts the notes the SM has to give.

Before continuing further with some of the things an SM must do to be successful in giving acting notes, it might be a good time to return to Chapter 7 on working relationships and review the SM’s relationship with actors and star performers. Having in mind some of the ways actors work and may react will allow greater success in giving acting notes. Following are some guidelines to use in giving performance notes:

- First and foremost, the SM must approach totally egoless. If the SM has any personal agenda, like wanting to display and express his “directing” ability and talent, as sure as there is sunshine on a cloudless day that will be clear to the performer.

- Before approaching an actor with a note, the SM needs to be prepared. If the acting note is questioned or challenged by the actor, the SM must be ready to talk intelligently about the script, the action, the plot, the blocking, the director’s choices, and all the other parts of the director’s work. There should be no uncertainty in the SM’s mind about the things surrounding a particular note the SM has given. Upon being questioned or challenged, the SM cannot be defensive or protective, but must be clear and decisive in communicating any thoughts, observations, and what changes the SM wants the actor to make. The SM needs to have full conviction of what is being presented and have a strong foundation of support for the judgment and direction being given.

- Next, the stage manager must be certain not to step into the directing arena. It is important to establish this with the actors and remember that the SM is there as the director’s representative—there to maintain, not change. The SM must stay out of telling actors how to act and how to do things—that is their craft. The SM cannot become involved with their characterization, interpretation, or manner of delivery, or ask the actors to do things that are the SM’s choice and not the director’s. If there is any question in the SM’s mind about a particular note stepping over directing boundaries, the SM should not give the note until after having talked with the director.

- In the approach to the actor the SM must come as an emissary, an ambassador, and not as a figure of authority who has come to judge, criticize, blame, and demand change.

- After giving a note, the SM needs to step back to see the actor’s reaction. Some will graciously take the note, even thank the SM, and act on the note for the next performance. Others will take the note silently and leave without a reaction. The SM will have to wait until the next performance to see if the note had any effect. Others, to varying degrees, will be more vocal and expressive, either in generating conversation or in challenging. The SM needs to listen carefully not only to what the actors are saying but to how they are saying it—the intensity or verve of the delivery. The SM must keep in mind that each actor is the ultimate source of his or her craft, performance, and the character being played.

- With actors who are more extreme in their reaction and resistant in taking a note, the SM does not need to win but needs to do what is best for the show. If having further conversations with the actor will bring a resolution, then the SM can follow that course. If not, the SM momentarily sets the note aside and once again confers with the director.

Varying Performances

Most actors will improve, enhance, and embellish upon their performance, but will remain within the original structure, intent, and direction. Some actors are highly structured in their work. Once they find what works for them, they perform it the same for every performance. Others appear to be more spontaneous; however, upon a closer look, they too work within the structure that is part of the original design and plan—they just perform it differently each time. Then there are the performers who seem to be driven to wander and experiment, even after they have improved, enhanced, and embellished their work. They may be bored or need excitement and stimulation to get them through the performance. With this kind of performer, the SM’s work becomes intensified and all of the suggestions on giving acting notes are put to their greatest use.

The SM’s Transition in Giving Performance Notes

In giving performance notes to actors, the SM must start by taking it slowly and must build a performance–note-giving relationship. This relationship begins in rehearsals and escalates during techs when the SM gives notes concerning technical matters. From there, the SM can transition into giving acting notes, first by giving positive and complimentary notes. By the time it becomes the SM’s responsibility to give actors notes during the run of the show, it is possible to transition into giving the less favorable notes without much resistance.

Giving Stars Performance Notes

For the most part, the SM should play a limited role in giving star notes. To have gotten where they are, most star performers have perfected their craft or at least know what they must do to maintain their star status. If there is a question in the SM’s mind about what a star is doing in a performance, the SM should first confer with the director or, if the director is not available, with the producer. Star performers have created a certain style and persona. In most cases this is what the audience has come to see, and this is what the star will give to them. It is often this style and persona that makes the star perfect for the part and unique in playing the role.

There come, however, in every SM’s life, times when a star must be given a performance note. The SM’s experience will be wide and varied. Most stars have respect for the SM’s work and appreciate the SM’s care and concern for the show. On occasion, a star performer may even ask the SM to watch a particular thing in the show and give an opinion. Other times, a star’s reception to an SM’s acting note can be silent, cold, and possibly painful to the SM. The best an SM can do is follow the suggestions listed previously for giving acting notes and guard against giving notes that work against the star’s style, persona, or way of working.

Greater Latitude for Star Performers

The American Declaration of Independence proclaims that all people are created equal. In theatre, this is an ideal all SMs would like to follow with the people in their care and charge. However, the truth is there is a chain of command—an order in which people are considered and treated according to their position and status. Among the cast members, this fact holds especially true for the star performers. The producer, director, and SM allow stars a greater latitude and degree of freedom for change and expression than they allow other performers in the show. In extreme cases, they will allow a star performer to do something in a performance that they would not allow another performer. By all ideal standards, this is unfair, sets up a double standard, and perhaps places the SM and the others in authority in a hypocritical light. The beginning SM who detests this notion and vows not to play such favoritism eventually succumbs. In efforts to treat star performers the same as everyone else, the SM may end up standing alone, unsupported, and may not work again for that star, producer, or director.

Delivering Other People’s Performance Notes

For any number of reasons, the producer or director will have the SM deliver performance notes that should actually be delivered by the producer or director. Whenever the SM is put in this position, and the SM knows there could be a volatile or explosive reaction from the performer, the SM needs to take some steps before doing this job. If the note was not dictated in friendly or positive terms, the SM should edit and clean it up—taking out the things that might be inflammatory. In this editing, however, the SM cannot lose the note’s content or its meaning and intent. Upon delivery, the SM needs to make it clear from the start who the message is from and that the SM is only the messenger. This point cannot be stressed enough. On hearing the contents of the note, the actor may become upset and filled with feelings that lead to forgetting who the originator of the message is and taking out these feelings on the SM—the deliverer.

A Final Step: Follow-Up

There remains still another step for the SM in giving performance notes. The SM must follow up on the note by watching to see if the actor has, in any way, responded to the acting note and made the desired change. If the actor has changed and all meets the SM’s approval, either after that performance or before the next the SM should have a follow-up conversation with the actor to thank the actor, express the SM’s appreciation for the actor’s work, and ask if the actor was comfortable with the change.

If the SM sees that the actor has responded to the acting note but the actor’s performance is still not what the SM thinks it should be, the SM first expresses thanks and appreciation, and then has further conversation to lead the actor into the desired change. The SM will, once again, need to be specific and clear in what is being asked.

If after giving an acting note the SM does not see any change in the next performance, the SM should wait one or two more performances. If by that time the actor still has not made any attempt to change, the SM needs to approach the actor, generating further conversation on the acting note.

It will be easy to follow up and thank the actors who have accepted the acting note and have made the change. It will be more difficult with the actors who do not. In not acting on the note, the actor may have forgotten, may be demonstrating resistance, or may be trying to turn the moment into a power play with the SM. The SM does not know which until approaching the actor again and initiating further conversation. The SM must follow through and do this final step on all the acting notes given.

The ASM Takes the Stage

It has been stated several times throughout this book that the ASM must be knowledgeable and capable of doing all of the work of the PSM. With such aptitude and to be a successful ASM, the ASM must work in the shadow of the PSM. It is the ASM’s job to aid and support the PSM, do the work that the PSM dictates, fill in where the PSM is weak, or do the work the PSM chooses not to do. When the show gets into its run, it is time for the ASM to stand alone and display some of his or her talents and abilities. It is time for the ASM to start calling the cues for the performance.

During technical rehearsals, the PSM was very careful not to have the ASM tied up with work duties that needed to be done for each performance. During technical rehearsals the ASM’s job is to move from area to area, wherever someone was temporarily needed, and work as a troubleshooter or facilitator.

The ASM Prepares—Calling Cues for the Show

If the show is now frozen, usually by the end of the first week of the run and certainly into the second week, the cast and crew have worked out whatever problems they might have had in performing and the show is running smoothly. The ASM is not needed as much backstage, which leaves the ASM free to start calling the cues for the show. By the time that this moment comes, a good ASM has already begun preparing for this part of the job:

- The ASM has gotten approval from the PSM to sit out front to watch one or two performances. If the show is a musical, sitting out front is especially helpful because the ASM gets to see the show from another perspective. The ASM gets to see the lights and projections executed and the effects created. The ASM also gets to see the set moves—the scenery changes.

- After seeing the show, the ASM may want to spend a couple of performances backstage standing by the PSM and, while wearing a headset to hear the cues being called, watch the PSM throwing cue-light switches, scenes being changed, and sight-cues being called in protection of the performers.

- During the daytime, the ASM has made a copy of the calling script. From all he or she has seen from out front and standing by the PSM, the ASM studies the cues, visualizing the things that are to happen with each call. In addition, the ASM also goes to the theatre an hour or more early, sits at the PSM’s console, maybe even puts on the headset, and, sotto voce, begins calling the cues, giving warnings and standbys, and operating the cue-light switches for the rail and floor stage technicians.

The ASM’s Working Disadvantage

It is important that there is little difference between the PSM and ASM when calling the cues for the show. It is the ASM’s job, as much as possible, to duplicate and recreate the timing and calling of the cues as the PSM calls them. Unfortunately for the ASM, the crew has learned the show with the PSM calling cues and their timing is dictated by the PSM’s timing.

A second working disadvantage for the ASM is that while the PSM had the luxury of learning the show and making mistakes in techs, the ASM has no room for mistakes. The ASM is learning and calling the show during a performance, when the audience expects to see a perfect and professional show. It is important that as the ASM learns to call the show, the PSM stands at the ASM’s side with a headset on and is ready to correct any mistake or avert any possible disaster. Even after the PSM feels that the ASM is able to go it alone, the PSM should remain close by for one or two more performances.

Musical Shows

When doing a musical, to make it easier for the ASM who is first learning, it is a good idea for the ASM to do the first act for one performance, the second act for the next performance, and on the third performance do the entire show. This gives the ASM time to assimilate the enormous number of cues for each act that usually accompany a musical. By the end of the third week of the show’s run, the ASM should be navigating the ship as expertly as the PSM, creating the same theatrical magic.

Show Insurance: The Show Must Go On

Having the ASM call the show ensures that the show will go on should the PSM, for any reason, become unable to call the show. With the ASM calling the show, the PSM is free to go out front to watch performances or stay backstage to do company business and keep the show organized and running smoothly.

Updating the Blocking

One of the first things the PSM must do after the ASM has learned to call the cues is return to the rehearsal script and bring all the blocking up to date. If you recall, when the SMs go into technical rehearsals, the PSM sets aside the rehearsal/blocking script and the cueing script becomes the important book from which to work. Meanwhile, during techs and even after the show opens, more changes are made in the blocking. With techs being as they are, the PSM does not have time to note the changes made in the blocking and instead sets this part of the job aside with the promise that, once the show goes into its run, the PSM will return to bring the blocking up to date. This is now that time. The PSM might update the blocking either while sitting out front at the back of the theatre (as long as nearby audience members are not disturbed), or from one of the wings, as long as the cast and crew are not hampered. For further assistance, the PSM might go over the blocking notes with the understudy or even the performer. However, this is time consuming and can be taxing for the performer. The blocking has become so mechanical and ingrained in the actors that too much time may be spent jogging their memories.

The “Archival” Video

With today’s technology and the ease at which events can be recorded, there comes into the SM’s life another ray of light, making the job just a bit easier by being able to make an “archival” video of the show. This can be done with any of the video recording devices available. It would be a one-shot, one-angle view, with the camera framed on to a full view of the stage. There will be no editing, no closeups or changes of angle. Of course, all of this must first be approved by Equity and voted on by the cast members. Also the shop steward for the stage technicians’ union should be informed. This video is strictly to document the show. It cannot be shown or seen except for the SM to get most accurately the blocking into the blocking script and for restaging at a later time. It must remain with the production offices at all times.

Off the Record—a Confession and Denial: I must confess that for one reason or another, when all else failed and I was confronted with having to get the blocking for a major scene with lots of people, I have stolen off into a projection or spotlight booth and recorded that scene. Should it ever be brought up that I said this, I will take the fifth. Of course, after getting the information I needed, the recording was deleted. I say no harm, no foul. An SM must do what an SM needs to do to get the job done.

At this point in the show, the rehearsal/blocking script has been marked and erased many times and has gathered many other notes during rehearsals. It is strongly recommended that the PSM transfer the updated blocking notes into a clean script, which can then be used in understudy rehearsals and turned in to the producer at the end of the show as part of the production notebook.

Days Off and Matinee Days

According to Equity agreement with producers, the work-week starts on Monday and ends on Sunday. We have already noted this in Chapter 6, when creating the performance sign-in sheet, Figure 6-9.

The Equity rule states that after six consecutive days of work, the actors must have the entire seventh day off or be paid overtime. It further states that on the day after the day off, the actors cannot be called in to work any earlier than the half-hour call before the performance, unless the producer pays overtime and possibly a penalty fee. This gives the actors a sense of having had two days off. It is also agreed between Equity and producers that the actors will perform eight shows within the six-day period of work. Any more than eight performances in a workweek and the producer is obligated to pay overtime. Any fewer than eight performances means that the producer still pays the full salary, unless a different agreement has been reached with Equity. Depending on the type of contract, time off and the start of overtime can vary. This is where each SM must know the particulars of the contract under which he or she is working.

Traditionally, theatres are dark on Mondays, which becomes the company’s day off. For any variations or deviations from this workweek, the producer works out the differences with Equity. Rarely will a producer choose to have a performance on the seventh day. The cost can be too great.

Matinee Performances

Traditionally, matinee performances were on Wednesday and Saturday. With the expansion of regional theatre and civic groups producing shows, some producers found it was more convenient for their patrons, and they could draw a larger matinee audience, if they had matinee performances on other days. Some have chosen to have their matinee performances on Saturday and Sunday. The advantage to this schedule is that the company has its days free throughout the week, but starting with Friday night’s performance, the company performs five shows within a two-and-a-half-day period. If the show is busy, difficult, or a musical, this can be a grueling schedule.

Rehearsals during the Run of the Show

What! More rehearsals? Yes. Brush-up rehearsals, line rehearsals, understudy rehearsals, rehearsals for new actors, standby performer rehearsals, and put-in rehearsals all happen during the run of the show. As part of the different Equity contracts with producers, producers can call in the cast for a limited number of hours for rehearsals each week without having to pay them for this time.

Also there is the mandatory rehearsal required by Equity that the SM must schedule before each performance where there is swordplay, choreographed fights, or manipulation of loaded guns that might be dangerous or cause injury.

Brush-Up Rehearsals

Having rehearsal time once the show opens allows the director to make changes or clean up things during any part of the run of a show. Also, once the show is left in the SM’s hands, if the SM feels the show or a particular part of the show has fallen below performance level, the SM too can call a brush-up rehearsal. For the SM, brush-up rehearsals are not to redirect or make changes, but to get everyone back to the original direction.

Brush-up rehearsals can be as simple as having the cast sit in the greenroom to run lines, or as involved as having the performers up on their feet onstage and doing the blocking along with the lines. Brush-up rehearsals usually involve just the actors. If some of the technical elements of the show are needed during a brush-up rehearsal, the SM must get clearance from the producer to have a skeleton crew come in and pay for their time. For any rehearsal held onstage, whether using technical elements or not, the SM must know the policy of the particular theatre. Some theatres require a paid union technician to be present, even if it is only to turn on the work lights.

Line Rehearsals

If the cast has been away from the show for a period of time longer than the normal day off, the SM might choose, or even be asked by the director or producer, to have a brush-up rehearsal. If the show is not complicated and the SM is confident the actors remember their blocking, the SM might choose to have only a line rehearsal—a rehearsal where the actors sit around in the greenroom or out on the stage and run their lines. A good line rehearsal exercise that helps get the actors to remember their lines is to have them say their lines at double speed or as fast as they can and still be heard, remain intelligible, and maintain the meaning. This sort of exercise is jarring, taxing, gets the adrenaline flowing, and quickly brings the lines back to conscious memory.

Understudy Rehearsals

Enter another important part of the SM’s job. Equity rules require that the producer assign and pay Equity actors to understudy (U/S) certain featured roles within the show. Consideration for U/Ss starts as early as the audition period when the producer, director, and casting director choose actors for smaller roles with the thought of having these actors also U/S the larger roles—the principal roles. However, once the choices are made, the contracts are signed, and rehearsals to put the show together begin, very little work is done with the U/Ss until after the show opens. Then, all of a sudden, the producer, director, and even the SM realize that if the U/Ss are not ready and one of the principal performers becomes unable to perform, the show will not go on. There now comes a rush to have the U/Ss ready.

Often, the job of preparing the U/Ss is left to the SM. Sometimes the director will play a major role in preparing them. Neither the director nor the SM should have to spend a lot of time teaching the roles to the U/Ss. Throughout the rehearsal period, the actors contracted to U/S must, in addition to doing their regular parts in the show, also be working on their own, learning their U/S parts. It is the U/S’s responsibility to learn the lines, learn the songs (if the show is a musical), take down the blocking, and keep all changes up to date before they come to the first official U/S rehearsal with the director or SM.

If the director is conducting the U/S rehearsals, the ASM is required to be there to follow script, read in the parts without understudies, help set up whatever rehearsal furniture and props are being used, and use this time to further learn the show, as directed by the director.

The SM Must Be Prepared

Regardless of the U/S’s responsibility for being ready for the first U/S rehearsal, the SM must also be ready to work by having the blocking for the show up to date and having a good working knowledge of the script, the action, the character development, and so on. In addition, the SM must know the director’s work—the director’s intent, meaning, and interpretation. The SM also must be ready to work with an actor who has come unprepared. In U/S rehearsals it is the SM’s job to convey the director’s work to the actors who have either missed getting it themselves or not yet incorporated it into their performance.

Restrictive Guidelines

To work the U/S rehearsals effectively, the SM steps into the directing arena, but in a limited way:

- The SM does not direct the U/Ss, only prepares them. The SM leads them to giving performances in keeping with the director’s work and similar to the way the principal performer is performing the role. The directing has already been done by the director. The SM only mimics the director’s work. Whatever directing techniques the SM might use are only to get good performances from the U/Ss.

- Neither the SM nor the U/S is allowed to change the blocking or bits of business, or interpret the role in such a way that it is removed from the director’s work or so different that it will cause the other actors onstage to become distracted and possibly thrown in performing their parts.

The Soul of Understudy Work

With such restrictions, the art and craft of the U/Ss’ work comes in duplicating the roles (staying within the bounds and framework of the director’s and principal performers’ work) and at the same time making the roles their own, performing them as if the roles had been tailored and directed just for them. It is important that the SM know this of U/S work to be able to better prepare the U/Ss and lead them into giving good performances, thus ensuring the show goes on and artistic integrity is maintained.

An Assortment of Understudies

SMs will work with an assortment of U/Ss during their careers. Some will know exactly what to do as an U/S, staying within the bounds and framework of the role and yet making the role their own. They will come fully prepared and will require little to no direction from the SM. Others will be young or inexperienced and, on occasion, were chosen by the producer or director just to fill the requirements of Equity. With these U/Ss, the SM must know all about preparing U/Ss and apply that knowledge.

The Understudy Who Will Never Go On

To add to the assortment, the SM will work with those actors who are U/Sing the star role in a star vehicle. Either the star has the reputation of never missing a performance, or without the star’s performance the show will not go on anyway. Knowing this, some actors U/Sing a star role may slack off, putting little effort into learning the parts. With these U/Ss the SM must appeal to their professional senses, asking them to meet the responsibility for which they are receiving additional pay and, at the same time, aid the other U/S performers in rehearsing their parts during U/S rehearsals.

No Performance during Understudy Rehearsals

Every now and then an SM will work with actors who refuse to give a performance during U/S rehearsals. If the director were present, these actors would work at full capacity—for the SM they feel less motivated. Seeing this, the SM must ask the U/S to give some kind of performance if for nothing else than to be an aid to the other U/Ss rehearsing at the same time. A standard and stock reply is often, “Don’t worry! When I get into performance, I’ll do it.” This is unacceptable. The SM must know that the actors can perform the roles before they go on in their part. If the SM accepts this excuse and it turns out the U/S cannot deliver, not only will the show suffer but the actor’s poor work will reflect on the SM as not having done the job well. When an SM comes across an U/S who refuses to perform in rehearsals, the SM must be adamant in getting the actor to give some sort of performance.

In the same light, an SM may work with actors who have understudied the role before, or even performed it in another production. The first problem the SM may encounter is the U/S may want to perform the role as it was done in the other production. Another problem might be the actor may not want to put in the time each week at U/S rehearsals. Once again, the SM must be strong and insistent, working the U/S rehearsals to serve both the show and the other performers.

The Understudy’s First Performance

No matter how prepared an U/S might be, when it comes time for the U/S to go on in the part, the event becomes highly charged for most everyone. It usually comes on short notice and sometimes as the result of backstage drama. Often the U/S’s first performance is done with a lot of nervousness, excitement, anxiety, and adrenaline—somewhat similar to the feelings experienced for an opening performance. This is another one of those times when the company pulls together to help the U/S and keep the show at performance level.

For the first performance of an U/S the SM tries to redirect the charged energy to confidence and assurance. Over the PA, the SM officially announces to the company the U/S’s performance and asks for everyone’s attention and alertness during the performance, reminding them that if something is different they should go on with the show and that it will be corrected after the performance. Either the PSM or the ASM should be left free backstage for the U/S’s first performance. The SM needs to watch to evaluate the U/S’s performance and, at the same time, be ready to handle or avert any problems that might take place.

If the U/S should go on for a second performance, the SM must be aware of the possible letdown that sometimes takes place. After the first performance the U/S may become too confident, may be more relaxed, resting on the laurels and the success of the first performance. In anticipation of a possible letdown, the SM should talk privately with the U/S and to everyone over the PA. First, the SM thanks them for their good work, and then warns them of the possible letdown and asks that they once again become focused, alert, and concentrated.

Whether there is a second U/S performance or not, the SM should, on behalf of the producer and director, publicly thank the U/S. The SM should also privately express personal, sincere, and heartfelt thanks for the work the U/S has done, not only in the performance but in preparation for the role and throughout the U/S rehearsals.

Being an U/S is often a thankless job. Lots of time, energy, and good work is put in with little to no payoff. Those fantastic and wonderful stories about an U/S going on and becoming a star overnight happens only on rare occasions, and only in movies and plays such as All About Eve does such magic appear to be an everyday occurrence. The reality in most cases is that the principal performer returns and the U/S’s performance becomes a faded memory of a moment in time.

Scheduling Understudy Rehearsals

Equity has regulated the number of hours that can be devoted to U/S rehearsals each week during the run of the show. It also states that rehearsals for the U/S must be posted in advance. Once again, the SM must know the Equity Rulebook. The smallest error in timing or posting of the notice can cost the producer money.

In the first weeks of U/S rehearsals the SM should use all the time allotted by Equity for U/S rehearsals. Once all the U/Ss are up on their parts and the SM is confident they can perform their roles at a moment’s notice, the SM can reduce the rehearsals to once a week or to every other week, but cannot stop U/S rehearsals entirely.

Often, with posting of the first notice for U/S rehearsals, there comes a series of moans and groans. Even within the first week of performances, the actors have quickly adjusted to having the daytime off before going to the theatre to perform at night. In consideration of the actors, many SMs will schedule U/S rehearsals in the latter part of the day. This gives the U/S performers the whole morning and part of the afternoon free before they have to be at the theatre to rehearse. Then once they get to the theatre to rehearse, they are also there for the evening performance. However, in scheduling in this way, the SM must also allow time for the actors to have a meal break after the U/S rehearsal, and to be at the theatre in time for the half-hour call.

Whenever possible, and without expense to the producer, the SM should have the U/S rehearsal on the stage, hopefully with some or all of the scenery and props. However, in most professional situations, to have some or all of the technical elements requires having at least one union technician present. The most an SM can hope for is a bare stage with work lights. In other situations, the SM will hold U/S rehearsals in a rehearsal room, providing a minimum of props, sometimes only tables and chairs. Not having the props and scenery is not a great handicap to the U/S actors. They can see these things being used at each performance, and if they need to, they can come in early before a performance and work with the particular item. Perhaps at least one time during the run of the show, the SM might get the producer to agree to having a skeleton crew come in so the U/Ss can have a chance to work with the set, props, and lights before they have to go on or before the run of the show ends. On occasion, especially when on the road with touring a show, U/S rehearsals will be conducted wherever there is space—if not at the theatre or in a rehearsal room, perhaps in a hotel ballroom, conference room, deserted foyer or lobby, or even abandoned restaurant or nightclub.

Understudies Watching from the Wings

Throughout the run of the show, the SM should encourage all U/Ss to watch the principal performers from the wings during the performances. In doing so, however, the SM opens the door to a number of potential problems. The SM should ask the U/Ss to be certain to stay out of the sight lines of the audience and, as much as possible, stay out of view of the actors onstage. In standing in the wings, the U/S must also remain aware of entrances, exits, and scene changes, stepping off to the side until all is clear. These things are common sense, things the SM expects every actor working in theatre to know. However, actors often forget as they stand there, concentrating and studying their parts. On occasion, some U/Ss may become even less aware. They might mouth their lines or say the words in a soft whisper. For a performer onstage to see their U/S standing in the wings and hearing their lines being echoed is distracting, disconcerting, upsetting, and unsettling.

Understudy Rehearsals for Musicals

With musical shows, the SM’s work for U/S rehearsals usually is doubled. Not only is there more of everything, but the SM must also schedule and coordinate rehearsal time with the dance captain and musical director or conductor. In addition, the SM must have at the rehearsal space a piano. If the SM cannot use the stage to hold the U/S rehearsal and cannot get a piano in the rehearsal space, it is possible to have the actors sing the songs a cappella, and then for another time schedule a music rehearsal with a piano. Another choice is to have the sound person with the show record the pianist while playing in the pit, and then either put the music on CDs or in a thumb/stick drive. The SM can then play the recordings through the laptop.

Standby Performers

Standby performers usually are performers who are not in the show but who are standing by, fully prepared to step into a role at any given moment. Standby performers many times are performers who are known to be excellent performers in the business—performers who are capable of carrying this particular show, or perhaps any other show. Standby performers are chosen for the main principal or starring role. Sometimes they have performed the role in another production and are celebrities in their own right. They have been chosen by the producer for their box office draw, should the original actor or star become unable to perform the show. Today, standby performers are not used as frequently and can be found mostly standing by for a major show on Broadway.

There is no one particular policy followed when working with a standby performer. It is whatever the producer and director decide and set up. Sometimes the standby is required to come to the theatre for each performance and stand by. Some are allowed to leave just before the last scene. In more liberal situations, the standby may be able to leave by intermission, or may not be required to come to the theatre at all, but have with them their cell phone and be in a place where can get to the theatre in a short time.

Most times the director works with the standby, while the SM is brought in to give the blocking notes and read the other parts. Sometimes it becomes wholly the SM’s job. On those occasions, the SM might have some of the U/Ss join the rehearsal to do their parts, to aid and support the standby. Standby performers are usually extended more freedom in performing the role than is an U/S—especially if the standby has some star status. It is the SM’s job to observe, evaluate, and if the differences are great, try to lead the standby performer closer to what the director wants, or to confer with the director.

If the standby performer’s entry into the show is not on short notice, almost always the director or SM will hold a put-in rehearsal, calling in the cast and crew and using all the technical elements. If the standby performer has made any changes in the part, everyone will get to see them at this time.

Replacement Performers

Usually with a principal role or star performer’s role, the director is instrumental in putting in the replacement actor. With lesser roles, it is often left up to the SM. When called on to do this job, the SM once again must apply all the SM knows about the show and the director’s work. The SM must, however, be careful not to try to make the replacement actor a copy of the original actor. The SM must allow the replacement performer freedom but watch to see that the new actor’s approach and choices are not extremely different or in opposition to what the director wants. If, after working with the replacement actor and trying to lead the performance in the direction the director wants, the replacement actor remains resistant to change, the SM must consult with the director and possibly have the director come in to work with the actor.

Prompting or Feeding Actors’ Lines

We have discussed this subject on other occasions in this book, but it bears repeating. The SM should never feed actors’ lines onstage during a performance, or lead them in any way to believe that this will happen. Some plays and movies depict the SM as standing in the wings throwing lines to actors. If the SM ever does this, it is in the most extreme cases or situations. Starting with the first dress rehearsal, the SM reminds the cast of their responsibility for their own dialogue and assures them that the SM can no longer be available to save them by throwing lines as was done in rehearsals.

To feed actors lines with promptness and accuracy, the SM must follow the script 100 percent of the time. During the performance, the SM needs to be free to set up cues, call cues, watch the show, and handle any immediate problems that might come up at the moment. Even with a simple comedy or drama where the cues might be far and few between, the actors cannot be dependent on the SM. Just when they need the SM most, the SM will be doing some other part of the job during the performance and will not be watching their dialogue.

Creating Close Friendships

Now that the show is in its run, the SM has more time to relate in a social way and perhaps cultivate and develop some friendships within the company. This, however, is not always an easy thing to do, especially among the cast. By this point in time, the cast has bonded among themselves, creating pairs or little groups. In addition, the position of the SM is considered management, and there remains that gulf between the two working groups. Cast members sometimes feel restricted in what they can say or do when the SM is around. They welcome the SM in group social events, but when it comes time to go off and have a close and sharing friendship, the SM is not always an ideal choice.

It is sometimes easier for the SM to cultivate friendships among the crew members. As we have seen, the SM’s rule and jurisdiction over the crew is minimal, so there is less fear or stigma for a crew member to be seen chumming around with the SM. In having to work so closely together, the PSM and ASM will often bond and become good friends.

The Professional Experience

The work the SM does during the run of the show is similar from show to show. These experiences will be wide and varied, depending on the cast, crew, producer, director, and often the star. Any person who makes working in theatre a career cannot escape having at least one or two backstage experiences or stories to tell. SMs collect more than their share. Here are a few.

Star Power: Box Office Power

I worked with a well-known Broadway star who had originally created the lead role in a very famous Broadway show. He was now doing a West Coast production of the show and I, fortunately, was hired as the SM. The star performer was notorious for stopping the show whenever the spirit moved him. He would break character, step to the apron, and talk directly to the audience. The audience loved it. As soon as it happened in a performance, word spread quickly throughout the backstage and the ensemble performers would gather in the wings to watch. The man was clever, witty, endearing, and very good at ad-libbing. As the SM, I showed disdain and disapproval each time he did this, but secretly I enjoyed it and looked forward to when it might happen. However, as the SM, I felt it was my job to maintain the artistic integrity of the show. I approached the star and expressed my position and opinion. He complimented me for doing such a fine job, but told me directly to leave his performance up to him. I talked with the producer about this matter and he agreed with me, adding, “A nightclub is one thing, but not a Broadway book show!” I thought for sure he would have a talk with the star, but in the next weeks, the star continued. Box office receipts were up, so I can only guess that was reason enough to leave things alone. Another possibility might be that the producer did talk to the star performer, and the star performer told the producer pretty much what he told me.

Walking in an Elephant’s Shoes

In another show, a star performer who had not acted in fifteen years was cast in a supporting role. This actor made his mark as a star performer in the first part of his career, and then left the theatre to become a golf pro. After being absent from the theatre for well over a decade, it was quite a coup for the producer to have gotten this star.

It was obvious from the first day of rehearsals that the performer had become rusty in his craft and skills as an actor. He was stiff in his movements, he had great trouble remembering his lines, his delivery was flat and meaningless, and he did not listen to the other actors in the scene—he would cut them off before they were finished saying their lines. We wondered if the producer had made a mistake. The director spent an inordinate amount of time with this actor, but with little result. One day, out of frustration and anger, the director sent me off to another rehearsal room to work with this star performer and the two other actors in the scene, saying, “Drill him over and over until he learns the lines and listens to what the other people are saying.”

We ran the scene several times. Each time I took a different approach, trying to get the actor back to the basics of acting. He could take direction and do a thing one time, but he was unable to repeat it. This would have been fine if we were doing a movie. We would have filmed the scene and sent him on his way. This, however, was theatre; the actor needed to repeat his work over and over, first in rehearsals and then in performance.

I could see the star was struggling and suffering from many feelings. I had great empathy for him and tried to make the rehearsal easier. I complimented him on the improvements, I put some of my attention and focus on the other actors, and I tried to keep the atmosphere light and not filled with a sense of its importance. At one point in the rehearsal, after the star performer continually cut off the other actors’ lines, I said in a lighthearted manner, “Let’s run the scene again, and this time allow your fellow actors to finish their lines.” I then added jokingly, “You know how actors are, they want to say every word they have coming to them.” The two actors working with us chuckled, but not our star performer. He took major offense. He came at me with such voracity, such intent, fury, and venom, that I remained stunned and pinned in my chair. I dare not repeat his words, but in essence, he told me I was no director, and how dare I tell him how to act. He reminded me of his London experience, having worked with Sir Laurence Olivier, and of his Tony nomination. He said that I was a mouse trying to walk in elephant’s shoes. From his point of view, he was right, for this man had worked with some of the top theatre directors. His fury was great and he had not yet spent his feelings. He attacked further, becoming more personal. In the ten years of my experience up to that time, I had never experienced such an attack and I was not prepared for it. I had been criticized, condemned for mistakes, even ostracized by the cast for a choice or decision, but my self-esteem always remained intact. I lost my composure. I rose from my chair and strongly suggested the actor leave the room before I told him what I thought of him. I too was ready to attack personally, and I had plenty of ammunition stored in my arsenal. This, of course, provoked the star performer further and he came nose to nose with me, challenging and daring me to speak. The two actors looking on separated us. The one with the star performer led him out of the room.

I was now mostly upset with myself for having taken this direction and course of action. It was obvious the star performer’s words, expression, and feelings were not actually about me, even though the words were. Once again, the position of the SM came in the line of fire and this time it was in some other war. I asked for the room to be cleared and spent some time regrouping my thoughts and feelings. Meanwhile, the star performer went to the director and told him he was leaving, without giving an explanation. The two actors were able to fill in the director. When I returned to the rehearsal room, the director continued to work and said nothing. I had now become paranoid, and felt even worse. I saw the director’s silence as an indication of his disapproval for my actions, and in my mind his silence confirmed that I was wrong. I lived with that feeling for the rest of the day and into the next.

Next day at rehearsals our star returned. At first we kept our distance, barely acknowledging each other. However, I knew I needed to mend the relationship if we were to continue working together. I had hoped he would have approached me first to make it easier, but he didn’t. Finally, as we passed in the hallway, I took the moment to speak. I apologized for my behavior. I assured him I would never step beyond the bounds of SMing with him again. He too apologized or said what appeared to be an apology. He was not direct in his words and spent most of his time telling me what I did wrong. At the end we shook hands. We continued to work civilly together, but I could see I was not one of his favorite people. Ashamedly, I must also admit that he was not one of mine.

The Reluctant Star Understudy

On occasion a producer or director will hire someone knowing the individual will be a problem, but to serve themselves or the show, they go ahead anyway, knowing the SM will have to deal mostly with the problem person. In this particular case, an actor of some star stature was hired to play a lesser principal role. The performer wanted the lead because he had done it on Broadway as one of the replacement actors before the show closed. The producer of our show, however, chose another actor to play the lead part, one who was younger and more known to the public through his television and film work. As a backup, however, the producer wanted the star actor to U/S the lead role, a cruel twist of fate that sometimes happens in the entertainment business. The star actor reluctantly agreed and signed the contract. Our troubles with this actor began early in rehearsals when he started telling the director how to direct the show and how it had been done on Broadway.

In U/S rehearsals he became worse. He refused to do the role as the director had directed it, and after the first rehearsal he refused to come to the U/S rehearsals. The producer had to have a talk with him. This actor tried my patience further by complaining that the director did not come to U/S rehearsals to work with him personally. He also wanted to rehearse on stage with the scenery and props. Most of all, he was annoyed with me for asking him to turn in some kind of performance in rehearsals. I did this not to see if he was capable of turning in a performance, but to help the other U/Ss in working their parts. He argued that everyone in the business knew what he was capable of and the performance he could turn in.

One day in U/S rehearsals, I said out of frustration, “If I can get the producer to agree to let us work on the stage with set and props for two rehearsals, will you give an allout performance?”

“Sure,” my star U/S replied without hesitation or a blink of the eye. I was taken aback. What had I gotten myself into? No producer would go to such an expense for even one rehearsal, let alone two. I was desperate enough to approach the producer. I was surprised again when the producer agreed without hesitation.

What I did not know at the time was that the star U/S had already been to the producer on this very matter and been turned down. So when I presented my idea of working on stage with the set and props, the star U/S already knew it was not going to happen and agreed to strike the bargain with me. However, between the time the star U/S had spoken to the producer and the time I approached the producer, there had been a major change. The actor playing the lead was exercising the clause in his contract that allowed him to leave the show to do a movie. He would be gone for four weeks, but then would return for the last week in LA and the run in San Francisco. So now the producer was ready to pay the money to have the U/S rehearse onstage with props, lights, and scenery.

The producer did not, however, want word of this getting out. There were still two weeks before the lead actor left to do the movie. The producer did not want a rush at the box office in the next two weeks, and then have sales drop for the next four weeks. In addition, he was in the middle of his campaign for next year’s season subscribers and did not want anything negative to affect a subscriber’s decision in buying tickets, so he asked that I not say anything. Also, the producer wanted to keep this entire matter from the star U/S until the week before he was to go on. He did not want the U/S’s publicity people getting out the word. Meanwhile, the producer wanted me to rehearse the U/S with as many hours as I had allotted to me by Equity. When I told the actor we would be having U/S rehearsals onstage for the next two weeks, he too was surprised and regretted having made the bargain with me. He performed with some reservation in the first week. In the second week, when he was told of his going on in the part, he was more than willing to give a performance during U/S rehearsals.

Through the years I have remained friends with this reluctant U/S. One time when reminiscing, I told him of my deception. He forgave me and then confessed that at the time, he was just being a jerk. It seems he was having personal and financial problems and had taken the job as the understudy because he needed the money. He was hoping to do as little work as possible, thinking he would never go on.