18

The Touring Show

Touring shows have various names but are always touring shows; they just come in different Equity packages with varying pay scales and working agreements. Traveling with a touring show can be like a double-edged sword. On the one side, it can be exciting and adventuresome; on the other, it is difficult and tiring. On the exciting and adventuresome side, people with a touring show may go to cities and countries they might not have otherwise visited on their own. They get to meet and live among the people in different places, see the local landmarks and attractions, and make new friends. On the other hand, traveling with a show can be wearisome, moving from city to city, living out of a suitcase, being away from home, family, and friends. In addition, while paying the inflated prices of living out on the road, each person often has the continued expense of maintaining a permanent residence. The added expense of being on the road has been taken into consideration when Equity negotiated the touring salary, but the scale is often not enough and lags behind the rate of inflation. While on the road, company members must live sensibly or they will find their paychecks being consumed by expenses.

Types of Touring Shows

Some people love the change of being on the road while others merely bear it, doing it only for the work and pay. With differences in pay scale and working agreements, some tours are more preferred than others. In order of preference they are:

National Tour

This is probably the most coveted of tours, for the pay and the long number of weeks playing in one place. A national tour is a show that travels throughout the United States, playing in most major cities. This usually is a new show or a revised show that has just completed a successful run on Broadway. Some national tours are scheduled and booked in each city for only a certain number of weeks.

Once the engagement is finished, regardless of ticket sales, the show closes and moves on to the next city.

In recent years producers have started putting together one or two more additional companies of the same production before the original production on Broadway has played itself out. These companies are placed in cities where they are not in competition with the Broadway production or with each other, such as in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Houston, or Chicago. They are booked with an open-end run and remain until ticket sales drop. For the sake of the budget, the producers hire mostly local actors to play the smaller roles. By doing this, the producers do not have to pay for the housing of these actors and do not have to pay the touring pay scale. Sometimes in the second production the producers will feature the original star performer from Broadway, or the producers will hire another performer of equal stature and acclaim. On many occasions the PSM from the Broadway production will temporarily fill the position with the second company, with the intention of having the ASM take over for the run.

These additional companies are not a national tour in the truest sense. Depending on the agreement the producers have made with Equity, only the few who have been brought in from out of town fall under the terms of a touring contract. After the show has played itself out, either on Broadway or in one of the additional cities, the producers create a national touring company and travel the show to the other cities in the rest of the United States.

International Tour

This tour is similar to a national tour, but the show travels to different cities in different countries. The tour may be extensive, traveling to many countries and cities, or it may be limited, playing only one country and just a few cities.

Out-of-Town Tryout or Pre-Broadway Run

Traditionally, a new show destined for Broadway was produced in New York. Before its run on Broadway, the show had tryout performances in one or more nearby cities: Boston, New Haven, and Hartford were some of the popular choices. In recent times, some new shows have been put together in Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego, or even Canada, and have done a pre-Broadway run as a national tour, making their way to New York City. If the show proves to be successful on the road, the producers will follow through in bringing it to Broadway.

Regardless of the show’s origin, being with a new show and going into tryouts or a pre-Broadway run is not an easy job. Once the show gets on the road, the workday becomes more full and more intense with rehearsals in the afternoons, making changes and revisions. Some of the changes may be simple and painless, but others can involve a complete makeover of a scene or an entire act. On some occasions, scrapping the entire show and sending everyone home is the only remaining option. The work is hard, but the reward is great if the show gets to Broadway and has a successful run.

Regional Tour

Regional tours are similar to national tours, but they play a specific area in one part of the country, such as New England, the Southeast, the Midwest, or the West Coast. Most of these shows are produced by a regional theatre or production company and start out to play in just one city, but due to the success of the production, the producers decide to tour it to nearby cities and towns. The play dates in each town are usually short, sometimes only one or two weeks in one place. The more frequently the show moves from one place to the next, the harder it is for the entire company. The pay scale for an Equity regional touring contract is not as high as a national tour. On occasion, if the show proves to be extremely successful on the regional tour, the producers might consider taking it to Broadway.

Summer Stock

Working in summer stock is not touring in the traditional sense of moving from place to place. The members of a summer stock company are removed from their homes, friends, and family, but once they travel to the town where the production is based, they remain there for the entire season—usually from June to September, Memorial Day to Labor Day. Some summer stock companies are located in tourist or resort-type places. For those that are, in some respects it can feel like a vacation, with the members of the company participating in some of the local color and festivities, meeting new and interesting people. On the other hand, the pay is middle of the road and summer stock companies usually do a series of plays, or a repertoire of plays. This means rehearsing and mounting new productions during the day and performing at night.

Traditionally, summertime is a slow time of the year for people who work in theatre. Producers both in New York and other cities usually finish producing their shows in April or early May at the latest. They do not start up again until late summer or early fall. Despite the pay and intensity of the work in summer stock, people who work in theatre and do not have a job for the summer welcome having a summer stock job.

Bus and Truck

Bus and truck is just as it says—the company travels by bus and the technical parts of the show travel by trucks. The show usually is booked in a place for one or two weeks before it moves on. The living accommodations, though monitored by Equity, are less plush and more utilitarian. The transition time between the final performance in one town and the opening performance in the next usually is short, most times two days. If the show is simple and can be set up quickly, the transition can be limited to one day. The next town usually is a day’s trip away—sometimes only a few hours, other times twelve or fourteen hours. On many occasions, this travel day is also the cast’s day off.

Split-Week Tour

This is a whirlwind tour of traveling, setting up the show, and performing. Everyone and everything travels by bus and truck. The distance between each town is short. The show may arrive in a town on Sunday and by Monday night it is set up and ready for performance. The final performance may be on Wednesday night. That night the show is taken down, traveled to the next town, and once again is made ready by the second day.

To move so swiftly and set up in such a short time, the show has to be simple. The set, props, and costumes are minimal, and the technical setup has to take no more than six to eight hours. This kind of a tour is extremely diffi-cult and tiring for all. The members of the company literally live out of their suitcases.

One-Night Stand

A split week can seem like an eternity of time to play in one town when comparing it to a tour of one-night stands. The most practical show to do with this kind of a tour is a show that is done as a reading—a show in which the actors sit on stools, possibly reading their parts from scripts. The stage may be dressed with black curtains, the lighting limited to areas and specials, and for the different scenes the actors may arrange and rearrange their stools. The members of this kind of tour barely get the lids to their suitcases open before they are closing them and traveling to the next town.

Road Show

The term road show is generic for any show that travels. Many times a show that travels on a tour is cut down or streamlined from its original production. On occasion, scenes or dances may be cut from the show or cut down to be less strenuous. The scenery, lighting, and sound are almost always simplified.

Equity Taking Care of Its Members

Through the work of Equity, some very high standards for working conditions have been established for the actors and SMs of touring shows. There was a time when actors went out on the road and were at the mercy of the producer. Some producers were very honorable and caring, but others treated the actors as second-class citizens, having very little concern or consideration for their needs or working conditions. Today, Actors’ Equity monitors carefully every touring show under its jurisdiction, seeing that pay scales are met, working conditions remain in accordance to contractual agreement, and the members are cared for in whatever events or circumstances come up while on the tour.

The Company Manager, Touring Manager, and SM

Only on a large show with a big budget will there be both a company manager and a touring manager. Whenever possible, producers will have only a company manager. In many ways, the parts of each job are similar. When both managers are traveling with a show, the company manager is generally in charge of the company, making travel arrangements, setting up housing in each city, and caring for the daily expenses and general budget. The tour manager, on the other hand, deals mostly with the crew and technical parts of the show, making the arrangements to transport the equipment, dealing with the local union and crew, and often traveling to the next city two or three days in advance to see if the next performance site is prepared to receive the show. The company manager works closely with Equity, knowing the rules and regulations, while the touring manager works closely with IATSE, knowing their rules and regulations. In the absence of a tour manager, the company manager also does the tour manager’s work.

With the presence of both a company manager and tour manager, the SM’s job is made easier. The SM’s attention and efforts may be focused on maintaining the show and giving more personal attention to the cast. If there is only a company manager, the SM may be called on to aid the company manager in whatever way the company manager asks. In the absence of touring and company managers, the work of these positions is divided among the production office, the TD, and the SMs.

The Wear and Tear of Touring

Touring shows, especially ones that play in towns for short periods of time, move frequently, and have one or two days’ transition time from one city to the next, from one setup to the other—and are hard on everyone involved.

The Road Crew

The road crew consists of the heads of the various technical departments and their assistants. Moving the show from one place to the other is toughest on the road crew who travels with the show—the roadies, as they are affectionately called. From the moment the curtain goes down on the final performance in one city and rises on the opening performance in the next, their work is continuous, stopping only to eat and get some sleep. They must strike the show, get the technical elements and equipment securely and safely packed for travel, travel to the new location, set up the show, and have it ready for the opening performance.

The SMs

For the SMs too, each move is a major event. Not only must they pack out their part of the show, but they must oversee the travel day for the cast. Once they are in the new town, they must set up shop at the new facility and see that the show is ready for the first performance, which might mean having a dry tech, running cues and scene changes without the performers in order to give the local crew the chance to rehearse what they must do. No less than two weeks in a town is a welcome schedule for the SMs as well as everyone else in the company. With a two-week engagement, the cast and crew can have the following weekend for rest and personal time.

The Performers

Actors probably have it easiest in touring. After the final performance at a location, they are responsible for clearing out their dressing rooms, taking their personal belongings, and seeing that dressing rooms are left clean and in respectable order. Most touring shows will travel the actors’ makeup kits for them. It is the actors’ responsibility to clearly mark their cases with their names and put them in the travel container provided. The prop department becomes responsible for traveling the makeup kits. Once the actors’ work is done after the final performance in a town, they can return to their living quarters to get some rest and be ready to travel to the next town.

The Sms Anatomy of a Touring Show

Here we are again going into the “anatomy” of a thing as we did in Chapter 2, “The Anatomy of a Good SM.” Now it is the anatomy of a touring show. To better understand and visualize the makeup and nature of a touring show, know that it is divided into three parts:

▸ Part One: Closing out the show and packing. Within this part there are two phases:

Phase One: Making preparations to close out the show

Phase Two: Striking the show and packing it away to travel

▸ Part Two: Traveling the show—cast, crew, and all things technical.

▸ Part Three: Settling into the new town and venue—getting the performers settled into their new living quarters, getting the show technically set up in the new venue, and making the show ready for the first performance.

These are the parts and phases to a touring show in which the SM works in moving the show from one town or city to the next.

Part One: Closing Out the Show and Packing

In the anatomy of touring a show, it might seem unusual to start with closing out the show. However, once a show is on the road, the cycle of moving the show and company from one place to the other begins with closing out the show. Closing out the show and packing to move it to the next town is different from closing out the show permanently at the end of its run, which we will discuss in the next chapter. Closing out a show on the road means taking things apart, keeping every nut and bolt, every costume and prop, and every scrap of administrative paper, and packing them away neatly and safely so they can be traveled, set up, and used in the next place.

The Producer’s Transition Time

The transition time between the final performance in one city and the opening performance in the next is an expensive time for the producer, not to mention the box office downtime. In concern for budget and costs, the producer keeps the transition as short as possible. The time the producer allows for this is often ideal time and not realistic time. The producer allows only for a perfect experience with no problems or setbacks. Whenever possible, and with Equity’s consent, the producer will travel the cast on their day off. This saves the producer from losing still another day. The SM can give the actors some compensation for this personal time lost by delaying their rehearsal call at the new theatre until the last moment possible, which is usually in early or mid afternoon on the day of the opening performance.

The Two Phases to Closing Out a Touring Show

As stated above, there are two phases in closing out a show while on the road. The first phase is in preparation of moving out. In other words, the SM and each department does whatever it needs to do in advance to ensure that once the strike and packing begin, things will go smoothly, quickly, and safely. Once the strike and packing start, there will be no time for anything else. For the most part, preparations for the move begin in the last week of the run in a particular town, and get finalized in the last two or three days before the final performance. In some situations, the company manager begins preparation work for the next location even earlier.

The SM’s Preparations

In the final week in a city, preferably at the beginning of that week, the SM posts and passes out a schedule, along with pertinent information such as addresses, phone numbers, flight information, and procedures to be followed for the trip to the new location. This schedule is produced in conjunction with the company manager plans, reservations, and arrangements. The SM confers with the company manager and gets approval before the schedule is posted and passed out. Also as a service to all, the SM might email this notice and information to all so that they have it on their smart phones to refer to should they forget any one piece of information.

Next, the SM consults with the company manager, checking to see that all advance, follow-up, or confirmation calls for travel and housing have been made for the next town. If there is no company manager with the show, the production office usually handles this business. In such cases, the SM confers with the production office. When the production office is handling this business, it is wise that the SM also call to confirm things; it is more assuring if the SM has direct conversation with the people with whom the SM will be dealing in the next town, checking to see if everyone is coordinated, is working in the same time frame, and has the correct arrangements and information.

Another important matter in preparation to moving is to see that a housing list for the next town is put up in enough time for the members of the company to sign up. Once again, the company manager handles this business, but in the company manager’s absence, the SM does it. Equity has some very specific requirements, restrictions, and rules governing housing. The SM needs to be familiar with the details and see that they are followed. So it is up to the SM to have studied this part of the Equity Rulebook to make sure there are no infractions.

Last on the SM’s list of things to do is something for him- or herself. It may appear to be unimportant, but if left to the last minute it will be an inconvenience to all and maybe even set the SM behind in packing out his or her part of the move.

Sometime before the final day in a city, and certainly before the final curtain, the SM should ask the prop department or carpentry department to dig out from storage the crates and boxes that will carry the SM’s equipment. Usually the SM’s packing crates become buried, and after the last performance when the crew starts taking out their own crates, the SM’s crates become even more buried. To wait and ask for the crates after the final curtain and after the crew has begun striking the show becomes an inconvenience, because by then the crew heads and stage technicians are busy packing away their own areas.

The Last Performance

Often on the day of the last performance the feeling backstage is charged with a different energy. The SM feels it, not only from the performers but from the crew, too. Perhaps it is the excitement of moving to a new city, or maybe it is the anticipation of the whirlwind and marathon work of striking the show, packing, traveling, setting up in the new town, and having the show ready for the first performance. On occasion the feeling can be one of sadness for leaving a place where the company has felt most welcomed and has made new friends.

Advance Packing

It is unwritten but strongly believed that the last performance should be delivered with the same focus, attention, and energy as the opening performance. It is everyone’s intention to give their best. However, in anticipation of the move, people’s thoughts, especially the crew members’, slip into striking, packing, and the travel ahead. With any task that is difficult and tiring, it is natural for people to want to make the job easier. The crew has found that one of the ways to lighten the load is to start packing in advance. The prop and costume departments especially will start packing things while the last performance is still going on—things that have been used and are no longer needed for the rest of the performance. There is nothing wrong with the practice, and those who do it should be commended for their conscientious work and forethought. However, this practice should be of concern to the SM. Two things can happen. Invariably, something gets packed away that is needed later in the show, and on occasion the people doing this work tend to concentrate more on packing than on the performance. Sometimes they are late for a cue or miss it entirely. It happens, and every SM who has the experience quickly learns to make it a standard practice to announce at the half-hour call before the final performance that everyone must remain focused and concentrated on the show and not drift off to thoughts of packing and moving.

Let the Packing Begin

Phase two of part one—striking the show and packing it away to travel. With the fall of the final curtain the backstage becomes transformed into a metropolis of action, movement, and activity. The crew becomes a high-powered, fine-tuned, well-oiled working machine with all its parts performing efficiently and with speed.

The Company Manager and Touring Manager: At least two or three days before the final show, the touring manager’s office is packed away and the touring manager is off to the next town, making arrangements for the arrival of the company and show. The company manager, on the other hand, will often begin packing on the day of the final performance and can have the office closed out and packed away within an hour of the final curtain. Once the company manager’s work is done and he or she is no longer needed at the theatre that night, the company manager can return to the hotel to get some sleep and be ready to transport the cast, usually on the next day. It goes without saying that until the show is packed out of the theatre and the crew is either back at their living quarters or on the way to the new location, the company manager is on call.

The SMs: With the fall of the final curtain, the SMs too become whirling dervishes of action in packing. More than likely, while one SM was calling cues for the final performance, the other was beginning the process of packing. The real work cannot begin until after the final curtain falls. The SMs are responsible for clearing and packing away the callboard and having their office packed into the travel containers provided. They are also responsible to begin packing some of the things on the SM’s console, saving the more technical equipment for the sound and lighting departments. Once the lighting and sound departments complete packing the console, the prop department takes over and becomes responsible for moving the console and the SM’s stool, seeing that they get put on the truck and arrive safely at the next location. For assurance that the SM’s stool does not get left behind or picked up and used by someone else, the SM should have the stool clearly marked “STG.MGR.”

At some point in the SM’s pack-out, one of the SMs needs to go out to the front of the house to retrieve the Equity cast list, which was placed in the lobby when the company first arrived. The SMs are also responsible for seeing that the actors have left the dressing rooms and their general living spaces backstage in neat order, cleared of garbage, and have left nothing behind. In addition, they check to see that no pieces of costumes are left behind, and they make a note of those rooms or actors who left their dressing rooms in unsatisfactory condition.

Once the SM’s things are packed, the boxes and crates need to be securely closed with tape or locks. The boxes and crates also need to be clearly and boldly marked “STAGE MANAGER.” The prop department is responsible for traveling the SMs’ things. Upon completion of packing, the SMs check with the head of the prop department, asking where they should pile their boxes and crates so they will not be forgotten or left behind. Also, in thinking ahead to the arrival at the new theatre, the experienced SM has learned to remind the prop person that when the SMs’ boxes and crates are unloaded from the truck, they should be placed where the SMs can easily retrieve them. The SM knows these things can easily end up in some corner, buried, behind pieces of scenery or other crates.

There continues to prevail the myth that the SMs must stay at the theatre on strike night until the last piece of equipment is packed and on its way. That is the job of the TD or head carpenter. In a professional situation, the SMs are not permitted to do any work that is done by union technicians. If they stay until the strike and drag-out is completed, they will just be standing around watching. It is better for the SMs to return to their living quarters to get some sleep. More than likely the next day will be filled with the business of traveling the cast to the new city.

Before leaving the theatre that night, the SMs check with the company manager, the TD, and department heads to see if anything more is needed of them. Seldom are the SMs needed at this time. However, like the company manager, the SMs are on call for any matter that might need their attention.

Once the SMs know they are free to go, out of politeness, professional courtesy, and good politics, they go around to the house crew and local crew members to extend their thanks and appreciation and to say goodbye. This particular evening may be made of goodbyes, but chances are the SM who works a lot will be saying hello at another time.

Part Two: Traveling the Show—Cast, Crew, and All Things Technical

It is the goal of everyone in the touring company to move, set up, and have the show ready for the first scheduled performance in the new city. Almost always, the technical portion of the show travels by truck. Depending on the budget of the show, the distance to be traveled, and the type of tour, the company members may travel by bus, van, or airplane. Traveling has its degree of wear and tear on everyone. At best it is tiring. The most welcomed part is arriving at the next location, being set up in the new living quarters, and being back into the performances.

It is important to get the road crew to the next location as quickly as possible, to give them some time to sleep and be at the new theatre early to begin setup (the drag-in). In many cases the producer will fly the crew while the rest of the company travels by bus or van. If the company manager is not needed in the next town early, he or she may travel with the cast, along with the SMs. At least one if not both SMs always travels with the cast. If the company manager is present, the SM aids and shares in the duties. If not, the SM takes full responsibility.

Traveling the Cast

Either the company manager or the production office makes the arrangements and handles the business for transportation and the new living accommodations for the company. It is the SM’s job to be in communication with the company manager or production office and get from them whatever information is needed to create a schedule and lay out instructions pertinent to the particular move. A lot can go wrong, even on a short trip.

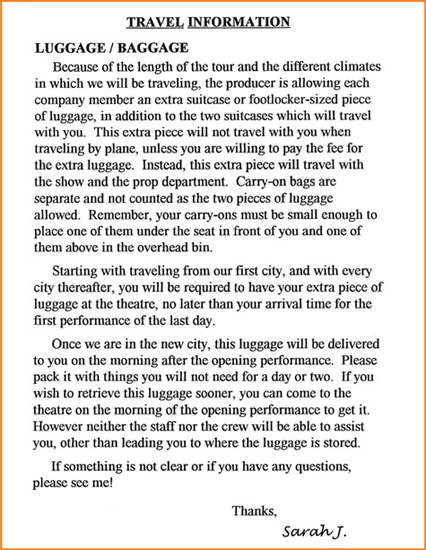

A Company Traveling Information Notice

Right from the start, even before leaving home base, the SM needs to get out to all in the company some kind of information/instructions notice (see Fig. 18-1). Note the detail into which the SM has gone, creating a picture of what the company members can expect and what is expected of them, laying out what can be done and what cannot be done and procedures to be followed, and possibly answering questions before they are asked.

Figure 18-1

Travel information to the cast telling them some of the procedures to follow and what to expect as they embark on touring with the show.

A Time Schedule for Departing the Old Town, Arriving at the New Town

In creating the schedule for departing one town and arriving at the next, the SM must once again be detailed, specific, and clear and answer questions before they are asked. The information is posted on the callboard and probably sent out via email, and if the SM wants to be a “noodge,” he or she might even hand out hard copies (see Fig. 18-2).

During the move, each group within the company is working within its own time frames, but at one point on the day of the first performance the SM must have in the schedule a time to bring everyone together to get the show working for the first performance at the new location. In creating the different time frames for the schedule, the SM is wise to schedule more time than is actually needed. This allows for emergencies, latecomers, or unexpected problems.

The Partner or Buddy System

With a large number of company members traveling, the SM uses any devices possible to aid in keeping organized and have control. Another effective tool is to incorporate the partner or buddy system. That is, whenever the group is traveling, each person within the group is assigned and paired off with another person in the company. They are not required to sit together when traveling or be best friends. On the day of travel they call each other, checking to see that each knows the schedule and is on time. Then when on the bus or at the airport just before departure or boarding the plane, each person looks around, checking to see if their partner or buddy is present. If not, they notify the SM or company manager.

When traveling by ground transportation and traveling long distances, there will be frequent stops throughout the day. It can be time consuming for the SM to do a role call each time the members of the company load onto the transportation. The SM merely reminds the travelers to check if their buddies are present before moving on. There is, however, a flaw in this way of working: if both people of a partnership are absent from the point of departure, there is no one to report their absence. For assurance and as a failsafe device, the SM can implement this system by assigning to each pair another pair of buddies. Their only job is at the time of boarding or departure, when each person of each pair looks around, first for the individual buddy, and then for the pair to which they have been assigned. Now there are four people checking on each other. The SM has reduced the odds of no one being

Figure 18-2

Schedule for the cast traveling from Chicago to Denver, detailing the times they must meet and the procedures they must follow from June 27 to June 29.

present to report on the others and can work with greater assurance, efficiency, and control.

Establishing Promptness

If the SM has been with the show since its rehearsals, the SM’s expectations for people being on time are well established. Being on time remains as important in traveling as it does in all parts of working in theatre. Neither the plane schedule nor the time to travel from one place to another, much less the opening performance in the new town, can be delayed or changed. At the meeting with the company just before starting out on the tour, the SM reminds everyone about being on time and adds the following as a statement of fact and policy:

Please note that any time you are required to be on the bus or be where the bus is supposed to pick you up and you are not there, that the bus will leave on the time it is scheduled and it will then be up to you to find your own way and transportation, be it to the airport or to the next city.

Having established such a firm and rigid rule, the SM must follow through on it should such a situation arise. However, the SM can build in an unknown and hidden period of grace. First of all the wise and experienced SM has scheduled the departure time at least ten to fifteen minutes earlier than what is needed, so there is a small window of time should any problems arise, like someone being a few minutes late. However, to create that period of grace, the SM will need to go through a bit of acting:

When are all seated, make your way on to the bus and do a check. If a person is missing, take out your cell phone and give the missing person a call. As the call is being connected, start leaving the bus, making your way toward the entrance of the hotel, keeping yourself in view of the cast members on the bus. Once connected, first find out if the person is okay, and then the reason for their not being at the meeting place. If the excuse is legitimate enough and if the person can get to the bus within the next five minutes, then offer that you will wait a few minutes more, but also warn that if they take any longer, the bus will leave and they will have to find their own means of transportation to get to the airport or to the next town.

Now this is where you as the SM can do a bit more acting. To create that period of grace without the rest of the cast knowing, make your way back into the hotel and to the front desk as if you need to complete some unfinished or forgotten business. If within a reasonable time the person has not arrived, then return to the bus and with a sharp order to the bus driver, say for all to hear, “We can’t wait any longer. Close the door and let’s go!”

Persons Traveling on Their Own

There may be some members of the company who have made arrangements with the production office or the company manager that they will bring their car on the road and travel to each city on their own. For the SM this is a bit unnerving. It puts the SM out of control and leaves open a lot more possibilities of things going wrong that could result in the performer not getting to the next site on time.

The most the SM can do is instruct these people that before leaving each city they make sure the car is in good running condition and that they be in cellular contact, reporting their progress as they travel along the way. The SM must remind the person, however, that calling does not relieve them of their responsibility for being at the new location and on time to meet the schedule.

Luggage and Baggage Handling

The SM takes as much care and concern in handling and moving luggage as he or she does for the members of the company. For the people traveling, the contents of their suitcases are their life support—the necessities and comforts for living. For performers out on the road, the suitcase is their home away from home—the items that make them feel at home no matter where they hang their hats and set out their makeup cases.

Tagging Each Piece of Luggage

All luggage and carry-on pieces must be clearly and identifiably marked and tagged so if a piece is separated from the group it can be quickly recovered. The production company often provides tags or stickers with the name of the show. In addition, the SM sees that each piece is marked with the person’s name and three contact phone numbers: the SM’s cell phone, the production office, and the company manager’s cell phone number. The SM should instruct the company members not to put their home address or city. It is best to have the luggage remain where it was found. This allows greater control in retrieving it and cuts down on the time the lost piece is separated from its owner. If the SM provides the tags to the company members, it is most helpful at the baggage claim to have them in a bright fluorescent color.

Baggage Check-In

When traveling with a large company there can be well over a hundred pieces of luggage. Whether traveling by ground transportation or by air, the SM leaves all people responsible for their own luggage. It is their job to see that their pieces get loaded on the bus or truck. If they are traveling by air, they continue to be responsible for their pieces once they are at the air terminal, seeing that each piece gets properly tagged with the correct destination information and is sent off to be loaded on the plane.

Once again the SM facilitates and oversees—seeing that all do their part and that the bags get safely loaded on the ground transportation and none get left behind. If the company is traveling by air, at the air terminal the SM has the luggage unloaded at curbside and checks to see if the luggage can be checked in at this point. If it can, the individual bags are tagged as a group, but each person is still responsible to see that their bags are properly tagged and sent off. As a double check, the SM also keeps an eye out, seeing that the porters tag the bags with the correct destination and send the bags off to be loaded on the plane. If the bags must be processed inside and cannot be checked in as a group, the SM directs the group to the inside and sees that each person checks in his or her own bags.

Baggage Claim

When at the baggage claim in the new city, each person in the company continues to be responsible for retrieving their own luggage. This is when the colorful tags help as the different pieces come around on the conveyor belt. Meanwhile, one SM seeks out several porters with carts to help move the luggage, while the other SM checks and makes contact with the drivers of the ground transportation. Often, the drivers are at the baggage claim and make themselves known. After the luggage is retrieved and a head count is taken, the SM has the porters take the baggage to the ground transportation vehicles that take the company members to their new living quarters. Don’t forget to tip the porters.

Part Three: Settling into the New Town and Venue

This is the last and final part in the cycle of touring a show: settling into the new town and venue, getting the performers settled into their new living quarters, getting the show technically set up in the new venue, and making the show ready for the first performance.

On-the-Road Living

When arriving in each new town, the first thing to be done is for all to get situated and set up in their new living quarters—the SM, too, even before going to the theatre to begin working at the new venue. Between the time of arrival in a new place and the opening performance, everyone will be putting in a long day at the theatre. At the end of such a day, everyone should be able to return to the lodgings to rest, without first having to unpack and settle in. Unfortunately, often times the show crew members choose to go directly to the theatre and will settle into their living quarters at the end of the day.

Making Yourself at Home

An important key to living on the road is to not live out of the suitcase—unpack, especially when living in a hotel or motel room. Even if it is for only a week, use the drawer space, hang things in the closet, set toilet articles out on the counter, create a kitchen area for snacks, set up your music, move the TV for best viewing, and set up the desk for your books, writing material, and laptop. In fact, after the suitcases have been emptied, put them away. As for split-week engagements or one-night stands, there is no choice but to live out of the suitcase. Even then, living can be made tolerable and convenient by packing neatly and putting things in departmental groups. Then in a matter of a few minutes you can place your luggage on countertops and about the room.

Living Accommodations

Living accommodations, though monitored and regulated by Equity, vary greatly. Some places might be upscale and swanky, while others, though nice, are very basic. Most will be at hotels or motels, usually single rooms, but if they are available and members of the company choose, they can share an apartment. At times, the entire company will stay in one establishment, and at other times they might be split up, living in two or three different places. Information for living accommodations usually is posted on the callboard several weeks in advance of each city, allowing enough time for the cast members to sign up and for the company manager or production office to make the arrangements and confirm the reservations. Once the company gets to each city, it is up to the company manager or SM to keep track of who is staying where and create a list of room numbers, along with the phone number for the front desk and possibly the manager’s office.

The Temporary Callboard

From the start of the tour, the SM establishes with the company members that for the first few days at each new city, a temporary callboard will be set up in the lobby or entrance area to the living accommodations. This board will be whatever the hotel can provide and will contain only the most immediate information needed for the cast. The company members are responsible for checking this board until the official callboard is set up in the theatre and everyone is settled in and performing.

The New Performance Site

Sometimes the theatre is located just around the corner or a few blocks away from the living accommodations. Other times it may require transportation to get there. By Equity rule, the producer must provide transportation if the theatre is over a certain distance from where the cast members are living. The producer may pay for the use of public transportation in the city or may provide a bus or van that will pick up the company members each day. In a big-budget show, the SMs may be fortunate to have a car at their disposal, which is for staff use and has been rented by the company.

Also, each theatre will be unique. Some will be brand new with state-of-the-art equipment and spacious dressing rooms for individuals as well as ensemble performers. Others may be historical landmarks, with a raked stage, sumptuous decor, and dressing rooms going up three or four flights of stairs. There will be one or two theatres that are just downright old and almost unusable, forcing everyone in the company to do what they can to set up the show and live in the backstage space.

The Show Crew, House Crew, and Local Crew

We have already met the show crew—the heads of the different technical departments that travel with the show, also called the roadies. When the show arrives at a performance site, the show crew meets up with the house crew—the stage technicians hired by the performance site to head the technical departments at their theatre. These two groups, the show crew and the house crew, join forces to set up the show, work the performances, and strike the show at the end of its run in that particular city. However, with most shows the show crew and the house crew are not enough to do the job. More stage technicians are needed. It would be extremely costly for the producer to travel a full crew. Instead, the additional crew members are picked up in each town—the local crew. The producer’s office, tour manager, company manager, or TD handles this business, making the arrangements for the additional crew members through the IATSE office in each town. Only in rare instances does the SM have anything to do with this work.

For the most part, stage crews are the same the country over. Only the accents or colloquial expressions may differ. They are glad to have the show in town and glad for the work. Time permitting, they will guide the company members to some of their landmarks and local color and offer their brand of hospitality.

A Mini-Tech

Yes, it is back into technical rehearsals! To one degree or another, everyone traveling with the show repeats the work done in technical rehearsals when the show was first being put together. The difference is, the technical kinks have been worked out and everyone is more experienced in the setup. It is now a matter of working with the new crew, teaching them what to do during performance, and resolving any problems that might come up in putting the show in this particular venue. With the transition time being so short from one city to the next, the pressure and urgency in this mini-tech can be great, and the hours for the crew and SM just as long as in the original techs.

Setting up at a New Performance Site

The work procedure for the SM in setting up at the new theatre is just as it was laid out and described in Chapter 15 on technical rehearsals. For review, this might be a good time to turn back and scan that part of the chapter, but the following is a checklist of the things the SM must do:

- Meet the local house crew and house person.

- Start set-up of the SM’s console.

- Tour the theatre.

- Talk to the people working the front of the house, set up the Equity cast board in the lobby, and discuss the procedure to be followed to begin each performance.

- From halfway down into the middle of the audience, walk across the audience from side to side checking sight lines, and do the same positioning yourself closer to the stage.

- Set up the SM’s office, be it in a space for that purpose or in some dressing room backstage—if nothing is available, then where the console is located.

- Assign dressing rooms (keys and nameplates, and make a schematic drawing of the room assignments).

- Set up the callboard.

- Post directional signs (if needed).

- Check to see that quick-change areas are set up.

- Post show rundowns throughout the backstage areas.

- Lay in white tape backstage for sight lines and places where it is needed for safety.

Putting It Together

On the afternoon of the performance, the SM uses this time to once again put the show together. If the show is technically simple, the SM has a dry tech to teach the new members of the crew the show. If the show is technically difficult or a musical, the SM will more than likely have a cue-to-cue tech with the cast and crew.

▸ The Cast: With each new performance site, the cast needs time onstage. With a musical or a show with diffi-cult blocking, the performers need to go over the spacing and sight lines for the new stage. They may need to run certain scenes and most definitely one or two of the dance numbers. They will also need to do a sound check.

▸ The Orchestra: If the show is a musical, the producer will more than likely bring with the show only the conductor or music director and certain key musicians: the assistant conductor, who usually is the lead keyboard person; maybe a base player, a trumpet player, or lead violinist if their particular instrument is important to the score; more than likely a drummer; and if the show requires, a percussionist. The rest of the musicians are picked up locally. Again, the production office, the company manager, or the conductor handles this business and makes the arrangements with the local musicians’ union.

The orchestra is brought in on the day of the performance. Sometimes they work in the orchestra pit while the conductor runs them through the music. Other times, they will work in the morning in some other place and come to the theatre in the late afternoon to work in the pit, working with the cast and doing a sound check.

▸ Making Changes: Each new performance site brings its own set of problems—some simple, some more complex, each affecting the show in some way. Sometimes it means cutting down the set or changing blocking, perhaps adding or eliminating cues. Remember, the TD is responsible for handling all technical problems and changes. The TD advises and apprises the SM of the changes, while the SM envisions how the changes might affect the show. The SM, along with the dance captain (if the show is a musical), will make whatever changes are needed on the stage with the actors.

Another Opening

No matter how many opening performances the company goes through while touring a show, each takes on an excitement similar to the first opening performance. The excitement is often generated by the presence of the local press, dignitaries, and special guests, perhaps people dressed in formal wear, and possibly a gala gathering after the performance at which the cast becomes the honored guests. For the SM, this opening performance excitement or keyed-up feeling may be due more to the fact that the local crew is new to the show and has had very little time to learn their parts.

The ASM

For the first two or three performances in a new city with a new crew, the PSM calls the cues to the show while the ASM remains free backstage to move about and troubleshoot any problems that might occur during the performance.

Additional Work for the Touring SM

Spike Marks and Taping

Practically every show has spike marks to which the SM must attend at each new performance site. They might be to mark the placement of a set unit, to tell the prop department where to put a piece of furniture, or to mark the center of a special light where an actor must stand. If there are only a few spike marks, as in a small straight play, the SM may have the spike mark locations committed to memory. If there are many, as in a musical, the SM should have them noted on a set of the personal floor plans that were created for the show, as demonstrated in Chapter 6, “Hard Copy.”

Many shows today, especially musicals, travel with their own floors. With automation being an important part of the scenery change, these floors are a must for they house all the mechanism that enables the scenery pieces to glide on and off stage. For the purpose of traveling and easy installment at each theatre, the flooring is made in four-by-eight-foot sections, and the sections are numbered. When the flooring is taken up at one performance site, the spike marks and dance/blocking numbers along the edge of the apron remain and travel with the different sections. When the floor is installed in its numerical order at the new theatre, the spike marks and dance/blocking numbers are in place. It is then the SM’s job to see if the marks are suitable for the particular house in which the show is now going to perform. If they are not, the SM changes them.

Installing these decks can take the good part of a day, so as time-saver, oftentimes a second deck is carried with the show. While the show is in its last week at one performance site, the second deck is sent ahead to the next performance site and installed so there is no delay in dragging in the set when the scenery arrives at the new site.

Additional Conversation with the Front of the House

During the time the SM meets and talks with the house manager and maybe even meets those in charge of the box office, the SM needs to check on performance times and matinee days. The SM should ask to see a copy of the play-bill the theatre will be giving to its patrons, and take a stroll out front to check the marquee for names, spelling, and billing. The company manager usually does this business, but if there is no company manager, it is important that the SM take up the slack. In addition, the SM will need to talk with the box office about cashing checks for the company members, how to handle the use of house seats, and complementary seats.

The SM may also have to locate the administrative offices for the theatre. If the show is not traveling with its own copy machine, the SM will need to make arrangements to use the theatre’s machine, offering to pay for whatever copies are made. As a matter of being thorough and efficient, the SM enters into his or her smart phone the phone numbers of the box office and the house manager.

Focusing the Show Lights—a Job for the ASM

Another job an SM might be required to do while out on the road is to assist the lighting department in focusing the lights at each new venue. More than likely the ASM is assigned this job. Once the lighting instruments are hung, the lighting department then needs to adjust each lighting instrument to shine on the stage as dictated by the lighting design and plot. This job requires two people—one who climbs up to each lighting instrument to adjust the lamp, and one who stands on the stage in the center of where the light is to shine. Actually, with the use of moving lights, the person standing on deck has become lessened or nonexistent. As long as the lighting instrument is hung according to the light plot, whatever focusing is needed can be done remotely by computer adjustment.

But at times when the lights need to be manually focused and adjusted, and the ASM is called upon to assist, then this is where the old way of doing things comes into play, and this is the time when the ASM must reach into the recesses of his or her academic training and bring to surface how things were done in less technological times.

As the lighting technician above moves the lamp into position, the ASM on the deck looks up into the light, telling the technician to stop when the brightest part of the light (the hot spot) is shining in his or her eyes. The technician then locks the lamp into place, shutters off the light to fill the area, and then moves the barn doors into place to prevent the spill of light into other areas. Last, the lighting technician checks to see that the safety chain or safety line is securely in place, and moves on to the next lighting instrument.

This is a time-consuming job for the SMs and is work in addition to all that must be done when moving into a new facility. SMs must learn to budget their time. The SM should always be working ahead of the time that something should be done. This allows for those pesky, unexpected things that always come to surface.

Spotlight Cues

In shows where there are many spotlight cues and more than one spotlight is used, the assistant to the head electrician traveling with the show usually doubles as the head spotlight operator. The assistant finishes helping in setting up the lights on the stage and then retires to the spotlight booth with the new operators, who have been hired as part of the local crew. The assistant teaches the new operators the cues and in performance calls the cues.

In the more economical, tightly budgeted touring shows, or in shows where the SM is required to call all spotlight cues during the performance, the SM is given the dubious honor of teaching the new spotlight operators their cues. With the transition time from one city to the next as short as it usually is, the SM seldom has enough time to go over all cues with the new operators and instead gives them a crash course. The SM explains the more difficult cues, familiarizes them with how the cues will be called, and assures them that the other cues are easy and that the SM will talk them through those cues during the performance. They will also have a chance in the mini-tech to become a little more familiar with the show.

Local Actors

With some touring shows local actors are hired as extras or to play small roles. In most cases the preliminary work of finding and hiring these actors has been done by the production office, tour manager, or company manager. However, once the company gets in town and while the show is being set up, it is the SM’s job to rehearse these new people and work them into the show. With a musical show, the SM has the help of the dance captain and the music director or conductor. Even with their assistance, this becomes additional work for the SM and consumes time in a schedule already filled with things to do.

An SM Myth

It is generally believed that when a show is planning to go out as a touring show, the SM is responsible for making cuts or alterations to the technical part of the show to make the show easier to travel and set up at the different venues. In a professional company, the producer, designers, director, and technical director traveling with the show are in charge of making changes. The SM may sit in on their meetings and may make suggestions, but for the most part changes are dictated to the SM. Once the changes have been made, the SM returns to the charts, plots, plans, lists, and cueing script, revising them to reflect the touring show.

The SM’s Time of Supreme Authority

We said in Chapter 17, “Run of the Show,” that although the position and authority of the producer and director are ever present and omnipotent, once the show gets into its run and the producer and director have gone on to other things, the company manager, the tour manager, and the SM become the lead positions of authority. While out on the road, although the producer and director are but a phone call, email, or text away, the company manager, tour manager, and SM become even more supreme in their authority.

Living Together

When the show was rehearsing and playing at home base, there were many days in which everyone spent at least nine hours together. For the most part, everyone was on their best professional behavior and some of their more annoying habits or ways of living were either not as prominent or did not have the opportunity to display themselves. Now that everyone is together, traveling, living, working, and socializing throughout every day, people become more revealing, and there is greater chance for differences and possible conflict. In addition, people out on the road will sometimes act in ways they normally do not act when at their home base. Things that were acceptable or of little concern to them at home sometimes become more important while on the road. Some may miss being at home, or even resent being away. Others find a new freedom and sometimes act in ways that are different, unbecoming, unprofessional, or unacceptable.

The more extreme cases are easy for the SM to identify and deal with. It is the subtle ones, in which a person begins to complain a little more, becomes a little more demanding, or is agitated and irritable, that are difficult to deal with. None of these things are excuses or justification for poor or unprofessional behavior, but the SM who is aware of and understands how being on the road can affect people can more effectively serve and deal with the affected company members.

The Performers

The tone or tenor of the company will change once a show gets on the road. Most times the change is gradual and subtle, with little shifts in relationships. At first, being on the road is fun, like a holiday—the honeymoon period. Gradually, the company members gravitate to each other, forming little groups, often pairing up as friends, lovers, companions, or for purely economic reasons. The romanticized view of being on the road with a show begins to wear thin, while the more strident difficulties of traveling and individual personalities become pronounced. As in life, sometimes the relationships created last the entire tour and beyond. Sometimes the relationships end when the tour ends. For others, a relationship may end abruptly at any time during the tour. Most times the relationship ends quietly, but other times it can be drawn out and cause a disturbance in the company.

During the time the relationships are developing and flourishing the SM watches quietly. In an effort to keep the company in a positive light, the SM, either through request or through observations, weaves these relationships into the fabric of the company. The SM sees that certain individuals travel together, sit at the same banquet table, are assigned to the same dressing room, or puts their names together to share the same living quarters. When breakups or separations occur, the SM acts quickly and quietly, making changes and arrangements not only for the general tenor of the company but for the show as well.

The Crew

The individuals of the crew appear to be the more seasoned and experienced in traveling with a show and living on the road. They demand equal consideration and care but require much less maintenance from the SM or company manager. They seem to be more accepting of the hardships, complain less, carry less baggage, and require fewer gadgets and creature comforts to make them happy.

Cast and Crew

In other parts of this book we have discussed the relationship, dynamics, and separation that can exist between the cast and crew members due to the nature of their jobs. If the cast and crew are very different, perhaps incompatible on many levels, the relationship can take a turn and become strained. Being on the road can magnify matters. During the times when the show is moving from one city to the next, the crew becomes separated from the cast, being totally consumed with striking, traveling, and setting up the show, with little time to eat, sleep, and do personal hygiene. The cast, on the other hand, has only to travel to the next place, set up in their new living quarters, perhaps explore the local neighborhood, and be ready to rehearse on the afternoon of the day of the opening performance. If both groups are not aware of the other’s work, such a working situation can put more strain on the relationship. If the engagements in each town are short and the transition time between one city and the next is tight, the cast and crew have even less time together.

Despite the gulf and drawbacks, most cast and crew members overcome their differences, oftentimes striking up friendly and sometimes personal relationships. From time to time an SM will have a cast and crew who remain apart and separate despite any effort to bridge the gap. The reassuring part of such a relationship is that it never affects the performance. The atmosphere backstage, however, can be sterile. The SM will continually get complaints from each group about the other. An SM cannot prevent such a relationship from taking place but can deal with each group to keep things from escalating and perhaps affecting the show.

The reverse of a troubled relationship between the cast and crew, though welcomed, can create a new set of problems for the SM. They are now too friendly and sometime during a performance may forget about the show and become focused more on fun and good conversation.

The SM

The SM also feels and suffers all the highs and lows of touring the other company members experience. With each tour the SM should get better at stabilizing these personal feelings, living less at the extremes and more in the middle.

The SM’s working relationships with the crew, technical heads, and assistants remain the same whether out on the road or at home. While out on the road, the SM needs to give more care and attention to the company and more specifically to the actors than would be normal when performing at the home base. The SM needs to be even more accessible, listening to the complaints, problems, and concerns of the individuals no matter how small or insignificant they might appear. The SM takes an active part in helping to resolve situations and problems that could affect the show or company, but at the same time is careful not to become a caretaker. The SM does not take away an individual’s responsibility to be an adult, a professional, and in charge of his or her own life and actions. Some people want a caretaker or parent figure and will seek out anyone in the company who in the least way displays an inclination toward this kind of a relationship.

It is disheartening and destructive to the company and to the show to have a group of actors, stage technicians, and staff members who can’t wait for the tour to end. This feeling is infectious and highly contagious. All that is needed is for one or two people to become afflicted and it can spread. It is also foolish for the SM to think that the company will remain joyous and harmonious, free from conflict and strife. The SM needs to remain alert in the good times as well as the bad. The SM should see that as the different groups or couples form they do not operate to the exclusion of others or to the company as a whole. The SM must also be alert and take care not to get pulled into the different factions and special interest groups. The SM takes everyone’s interest into consideration.

The Performance on the Road

In all the time a show spends out on the road, the performance is least changed or affected. Only in extreme cases will actors take their problems out on the stage and let it affect their performance. Once the show has been tailored to travel, the show remains virtually the same. This is due in part to everyone being professional and the work the SM does to maintain the performance and artistic integrity. It is also due to the fact that once the scenery and props are in place, the audience is seated, and the lights on the stage come up, the real world momentarily disappears, while the imaginary world of the theatre takes over.

The Professional Experience

The following diary account was a photocopy left on my console while I was traveling on the road with a show. To this day I do not know who left it there. No one ever came forward to ask, “Did you read the article I left you?” No one responded when I thanked the person over the PA system. This diary account, though written in a lighthearted spirit, conveys what an SM can experience in the course of a day while out on the road.

The article had been copied directly from a newsletter published by the Stage Manager’s Association in New York. At the bottom of the first page, separated from the text of the article, was the following information: Anne Sullivan was the recipient of the second annual Del Hughes Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Art of Stage Management.

Shamefully, I was not aware of this award until I went on the Internet. The Del Hughes Lifetime Achievement Award for Excellence in the Art of Stage Management is regarded throughout the theatrical community as the crowning achievement of a stage manager’s career. It pleases me to see that SMs are recognized and acknowledged, for outside of theatre it is a silent job—a job that always needs explanation when told to a civilian.

As I read the article Anne wrote, I chuckled, laughed out loud, and one or two times even cried out, “Oh! Ain’t that the truth!” I quickly bonded with Anne. It was as if she had walked in my shoes and I in hers. It was also a relief to hear another SM make the same comments, have the same complaints, and express the same feelings that I had. Being an SM is sometimes an isolating experience; as things happen with a show, there is only you and your assistant. There are times when you need to have the view and opinion of another SM and share your experiences.

As you read through the article, notice the change in times from back then to today. Notice the big and important phone problems and reference to the lighting board, which I am sure was either the one installed backstage or the “portable” ones brought in when more dimmers were needed for the particular show. Also the mention of “pit singers” and their problems, which today has become a thing of the past because now if pit singers are wanted, the ensemble performers are simply set up with wireless microphones, stand backstage, and follow the conductor’s lead as they watch on a monitor. Here is the article:

On the Road with a Major Musical, by Anne Sullivan

▸ Monday, 6:35 am: Arrive Nigends City via (bless the Company Manager) limousine after 21/2-hour ride from Nadaville. Dropped at Hotel Lataque. Given key to small dark room smelling of cigarette smoke. Windows won’t open. Dog starts coughing. Complain to front desk. Told to take it or leave; choicer selection of rooms might occur after 2 pm. Breakfast in coffee shoppe: bacon, scrambled eggs, toast, tea.

▸ 7:40 am: Walk to theatre carrying heavy briefcase and urging sleepy dog along. Can’t find stage door. Look for trucks. Can’t find trucks. Have a sudden and piercing fear that I am in wrong city. See one truck skidding along icy street. Finally sight all trucks except one—doubtless truck with deck and hanging goods. Follow truck to circular building without doors. Walk all around building. Dog shivering. Briefcase growing leaden. Tears freeze on face.

▸ 7:58 am: Still can’t find stage door. Enter by loading door. Boost dog and briefcase up. See stage. Stage left looks enormous. Stage right which is prompt side barely exists. Look at house. Cavernous. Balcony rail fully 90 miles away. No rational position for box booms. Seats taken out for sound man all the way over audience lift where he will be able to see little of second act. Orchestra pit presumably works on elevator. Is all the way down and completely out of sight now. Greet Advance Carpenter and Advance Electrician. Summon up big smiles and handshake as have not seen them for whole week. Advance Elec. says must use house fronts run off house boards. Ask where office is and if phones are in. Both look embarrassed and introduce House Carpenter who almost breaks hand with his shake. Ask who is House Propman. Old man drinking coffee in corner pointed out. Introduce self and dog. Ask where dressing rooms are and if phones in. Follow him on tour of dressing rooms. Find office. Phone is in. Pick it up. Phone not working. Breakfast for our crew provided by promoter: eat Danish and wash down with canned o.j.

▸ 8:15 am: Loading doors opened and unloading starts. Arctic wind fills backstage. Settle dog on packing blanket in office and go around all dressing rooms with assistants, Tillie and Spike. Tillie actually located stage door. Figure out assignment of dressing rooms, wardrobe room, hair room, and offstage quick change rooms. Note washer and dryer have been rented by theatre and hooked up. Only choice for pit singers is damp and dismal location in basement. Locate Company Manager’s office. Check their phone. Doesn’t work. Find place where orchestra rehearses. See our Propman and tell him where orchestra rehearses and where wardrobe and offices located. Show Sound Man pit singers’ hole and dressing rooms.

▸ 9:05 am: Stop on stage on way out front. Trucks are still unloading. Stage right totally covered up by scenery and crates. Electricians hanging upstage pipes. Carpenters screwing in deck downstage. Much shouting from fly floor as local flyman evidently deaf. Head out front. Very dark. Follow trail of old popcorn to front of house. Box office closed. Find cleaner and ask location of House Manager’s office. Go upstairs. House Manager not in but secretary is. Ask about phones. She says phone man coming. When? Soon. Ask for list of doctors. Coming soon. Find out where Xerox machine is. Ask for mail.

▸ 9:46 am: Check to see that musical instruments and music trunk on way to rehearsal room. Deck is down. Carpenters hanging downstage. Trucks still unloading. Stage left now filling up with crates. Musicians trickling in. Local wardrobe people arrive for 10 o’clock call. Tell them call is at 1 pm. Says so right on Yellow Card. Walk dog. Spike goes to orchestra rehearsal to make sure it starts without problems.

▸ 10:20 am: Trucks all unloaded and doors closed. Take off parka. Coffee and donuts served to crew. Have chocolate-covered donut and tea. Read mail. Try not to be distressed by bills which haven’t caught up. Tillie and Spike sort mail and distribute to our crew, put up name signs on dressing room doors, type out dressing room list with copies for stage door person, wardrobe, and hair. Find House Electrician and ask how he wants cue sheets for fronts written up. Start writing according to his specifications.

▸ 11:12 am: House Manager appears backstage. Very pleasant. Complain to him about phones. Says he will call phone company again. Give him sheet of paper with times of acts, late seating policy. Give him duplicate for Head Usher. Tell him we take 15 minute intermission. He wants 20 minutes for bar business. Compromise on 17 minutes. Discuss starting times and who rings bells. He says they always start promptly at 8. Bug him about doctor list. Ask about restaurants close to theatre and if anything open after show. Nothing is. Check stage again. See uneaten sugar donut. Eat it. Tillie and Spike unpack office and set it up. Wardrobe Supervisor arrives. Show him dressing rooms and washer and dryer. He nods sourly.

▸ 11:56 am: Phone man arrives. Walk dog. Feed dog. Go to McDonald’s with Tillie and Spike. Have Big Mac, French fries, choc. shake.

▸ 1:01 pm: Return to theatre. Phones functioning. Advance Electrician talking to infant daughter on ours. Advance Carpenter smoking large cigar in office. Dog coughing. Work resumes on stage. Units being put together. Electricians hang downstage pipes. Spike shops for stationery and first aid supplies, peanuts and tea. Tillie setting up callboard and posting dressing room list, Stage Managers’ and Company Managers’ phone numbers, doctor list Write out rehearsal schedule for week and post.

▸ 2:12 pm: Send Tillie to hotel to try and change all our rooms. Discover office phone numbers completely different from those given out. Call N.Y. office with new numbers. Type up stage manager reports for last week.

▸ 2:49 pm: Phone rings. Equity man wanting to know why cannot give vacation to chorus girl from company who is crying in his office. Explain that two other people already on vacation that week. Equity man not satisfied. Says she’s crying. Tell Equity man I can cry louder.

▸ 2:56 pm: Phone rings. It’s Star wanting phone number of doctor as feeling horrible. Get flyfloor cue-sheets and write-in changes for this theatre. Also write changes in prompt book.

▸ 3:06 pm: Bandage finger of local grip who bleeds over typed SM reports.

▸ 3:15 pm: Coffee and donuts again for crew. Eat cinnamon donut. Company managers arrive with tales of travel with cast. Commiserate and show them to their office.

▸ 4:37 pm: Electrician wants to know where SM desk is going. Go out and look at stage right. Though now cleared of crates still no room anywhere. Call Advance Carpenter. Ask him through clenched teeth where am I supposed to be. Advance Carpenter smiles sadly and shakes head and suggests I cue show from out front. No way. Advance Carpenter says I can’t use desk and that Electrician will have to make up board with cue lights. Electrician swears. Have desk moved to office. Walk dog to calm rage. Feed dog. Chomp on peanuts that Spike has returned with. Wardrobe Supervisor bursts into office with news that washer has overflowed. Go out front to tell House Manager who swears.

▸ 5:25 pm: Cleaners appear backstage with mops for flood already mopped up by dressers.

▸ 6:00 pm: Eat dinner at Holiday Inn with Tillie and Spike. Have overdone and overpriced filet mignon, baked potato, salad, pie.

▸ 6:59 pm: Return to theatre. Freezing. All heat off. House Carpenter laughs and says it is practice of management. Look for House Manager. His office locked. Get his number from ancient Propman who makes me swear not to reveal source. Call House Mgr. and order heat turned on. House Mgr. no longer pleasant. Go out on stage and start making focusing marks with chalk. Mark every 2 feet left and right and every foot going U.S. from portal line. Electrician brings walkie-talkie and asks if am ready to focus. Say yes and focus fronts with local electricians who are very good. Nine instruments lampless but all plugged correctly so must count blessings. Sound man plays Willie Nelson loudly to test speakers.

▸ 9:33 pm: Break for tea and three Pepperidge Farm cookies scrounged by Tillie. Spike changes trunk list after 3 actors call to report change of hotels, gives list to our Propman and then walks dog.

▸ 10:48 pm: Initiate discussions with our crew heads on whether to work until midnight or stop at 11 because all so tired. Everything in good shape so decide to stop at 11.

▸ 11:01 pm: Walk to hotel. Tillie has changed me to larger room with real air. Unpack clock, tea, oatmeal cookies, mug and dog food and clean shirt for tomorrow. Bed.

▸ Tuesday, 6:30 am: Wake. Wonder where am, take shower, make tea, eat oatmeal cookies. Feed dog.

▸ 7:45 am: Walk to theatre. Enter victoriously by stage door. Theatre nice and warm.

▸ 8:02 am: Start focusing pipes and booms. Local truck delivering trunks.

▸ 10:09 am: Coffee and donuts for crew. Eat glazed donut. Ask Tillie to phone star at 11 and ask about his health. Continue focusing. Wardrobe Supervisor says washer not fixed yet and how is he to do laundry. Ask Spike to bug House Manager and also to inform our Company Mgr. Tillie goes over SM cue lights with electrician.

▸ 11:29 am: Have to replug 8th pipe. Walk dog. Phone rings. Local police. Someone has reported seeing a trunk fall off a truck on Main Street. Tell Spike, who turns pale and rushes out. Tillie says Star hoarse and feverish but will go on.

▸ 12:00 noon: Lunch. McDonald’s. Repeat yesterday. Sound department making pink noise on stage.

▸ 12:46 pm: Return to theatre. Ask Wardrobe Supr. if washer functioning. Answer yes but dryer doesn’t heat properly. Ask Tillie to follow up with House Manager. Spike goes to Xerox spec sheets for next 3 towns turned in by Advance men. Makes enough copies for all crew heads. Tillie put cast sign out front and sticks names in alphabetical order. Sound men putting up stage speakers, moved #1 booms.

▸ 1:10 pm: Finish focusing 8th pipe and specials. Refocus #1 booms.

▸ 2:22 pm: Set winch limits with Winch Man. Wardrobe department setting up quick change offstage.

▸ 2:24 pm: Prop department moves refractory table and 5 chairs into space set up by wardrobe dept. Loud altercation into which Tillie steps. Compromise agreed upon and hated by both departments.

▸ 3:09 pm: Start getting ready for Tech rehearsal. Ask Tillie and Spike if all actors who didn’t travel with the company have called to check in. All accounted for except Principal Deputy. Spike calls Principal Deputy who is in hotel room and gives sass.

▸ 3:28 pm: Tech rehearsal begins. Do all flyfloor cues and winch setups. Look at light cues for each set. DSR winch grazes own legs whenever goes by. Tell Advance Carpenter. Tell Carpenter. Tell House Carpenter. Finally devise dance movement to avoid being hit by winch.

▸ 3:58 pm: Orchestra starts to move into pit. Discover pit elevator won’t work. Our electrician fixes. Raging Wardrobe Supervisor comes on stage. Washer overflowed again. Tillie leads him off.