CHAPTER 10

Stepping Up or Stepping Back: How to Know the Difference

Your entire life only happens in this moment.

The present moment is life itself.

Eckhart Tolle

Over the last decade, as I have spoken to hundreds of companies and as my colleagues have trained thousands of people on how to step up, one of the most frequent questions that emerged is this: How do I know when I am stepping up? In other words, what are the behaviors that tell me whether I am stepping up or stepping back? Since the choice to step up is made every day in how we act in the moment-to-moment situations of our lives, it is critical for us to understand what behaviors demonstrate stepping up. Once we are aware of what it looks like in practical terms to step up, we can then make a choice to move toward greater responsibility.

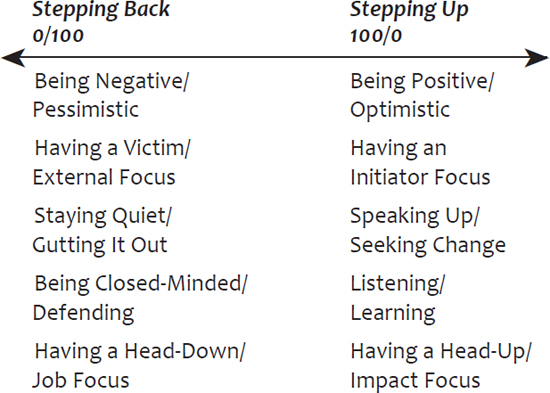

Over time we have identified five key behavioral features of stepping up. While these are not meant to be the only five behaviors that represent 100/0 (100 percent responsibility/zero excuses) behavior, together they allow each of us to determine, moment to moment, what it might mean to step up versus step back in most situations both at work and in our personal life.

These behaviors are mapped in a model called the Stepping Up Continuum, which visually depicts what it means to be taking responsibility. The model (fig. 2) has become a tool that organizations can use to communicate the stepping up philosophy while also serving as a powerful visual for each of us to ask: How am I showing up?

Figure 2. The Stepping Up Continuum

Being Positive/Optimistic or Being Negative/Pessimistic

The first way we know we are stepping up is if we choose to embrace positivity and optimism, asking what good may be possible in any situation we find ourselves in. Research by Martin Seligman (check out his books Learned Optimism and Flourish) has shown the many benefits of this mindset, including greater longevity, boosted immune systems, greater physical health, increased happiness, and greater resiliency in the experience of unfortunate events. Being positive is also a strong predictor of leaders’ being admired at work, according to studies at the University of Michigan (check out the work of Kim Cameron and others, including the book Positive Leadership). While many of us may quickly grant that optimism is a generally desirable quality, being optimistic is also a key first step in taking responsibility. This same research shows that optimists and those who choose positivity (and yes, this can be learned) react differently to potentially negative life events by focusing on what is possible in a situation.

Let’s take an example from the world of work. Pretend your organization is going through a great deal of change that will impact your job in many ways—some worrisome and some potentially beneficial. By choosing to focus on the positive aspects of the change—focusing on what we might gain in terms of new knowledge or even an increased capacity for adaptation in the future—we step toward action. This optimism moves us toward taking full responsibility for what we can do to maximize our learning.

Taking a negative or pessimistic posture, on the other hand, moves us toward passivity. We focus on the change that is being “done to us” instead of the power we have for choosing our reaction to that change. Negativity in any situation can also lead us to a path of chronic complaining, often about external things that we cannot change.

Complaining often is misconstrued as a form of stepping up. After all, we reason, by expressing my dislike of the changes around me, aren’t I taking action to generate change? Here I argue the opposite. Complaining and pessimism almost always move us toward passivity. Complaining becomes a substitute for action. Instead of asking what we can do or what we might learn, our complaining becomes a self-perpetuating vortex that keeps us passive. What’s more, by chronically focusing on the negative, we will often not take the time to become aware of the possibilities in a situation we may not have chosen to be in.

Since the very essence of stepping up behavior is to focus on the action we can take to change a situation we are in or our reaction to that situation, positivity is required to move us toward acting. Positivity and optimism make us curious about what is possible, while negativity and pessimism often lead to resignation in one form or another. Resignation by its nature is a form of stepping back—of not taking responsibility for what you can do in a situation, however small that action might be.

An extreme example might help demonstrate how optimism leads to action even in the most difficult of human situations. Viktor Frankl was an Austrian psychiatrist and a student of Sigmund Freud who was imprisoned in the Nazi concentration camp at Auschwitz. There is a profound passage in his memoirs where he writes of the moment he realized that the Nazis had taken everything away from him—his possessions, his family, his freedom, and even his dignity. But in that moment, he realized that there was one thing they were powerless to take away from him: his choice of how he would respond to them and to the situation he was in. While it is a great oversimplification, one could argue that in that moment, Frankl chose optimism. Even in the darkest of human experiences, his choice was to look for the positive response, however limited in that situation, which propelled him to action—in this case, the action to wonder what he could still do. Not only did he survive and go on to make a profound global impact through his writing, but he would later advocate persuasively for the role that optimism plays in mental health.

So here, “positivity and optimism” doesn’t mean ignoring the hard truth in a given situation but rather recognizing that the moment we focus on what is possible, we are propelled toward whatever action we can take. Earlier in the book we talked about the role naïveté plays in those who step up. The belief that one can do something is born in the choice to ask what is possible in any situation. Though action is the prime goal of stepping up, optimism is what propels us to that goal.

Think of the many ways this belief can apply. In an intimate relationship that has deteriorated, positivity about myself and our relationship will turn me toward what might still be possible. A relationship with a difficult colleague will never get better once I harden my mind to the possibility of change because that very pessimism will keep me from choosing action. There is nothing magical about this; it is simply a prerequisite to movement.

I experienced this in my own life when my mother was dying several years ago. The final week of her life in the hospital was both the most difficult and the most rewarding week of my entire life. Since I was an only child growing up in a single parent household, my mother was my rock, and it was incredibly painful to go through the process of letting her go. Yet at the very beginning of that final week, I made a conscious choice to be positive and optimistic. I asked myself this question: What will I learn about myself and about life in this final week? While the week was filled with an ocean of tears, it was also filled with a raging river of lessons. I do believe my choice to be optimistic changed my experience because all that week it forced me to focus on what I was learning, not just on my pain.

Having an Initiator/Action Focus or Having a Victim/External Focus

The second way we can tell if we are stepping up or stepping back in any situation is to check whether we find ourselves focusing on externals we cannot control or on our own power to act. Stepping up means that we focus on what we can do instead of what others need to or can do. It means that we don’t waste time focusing on external factors that we are unable to control. If we have the capacity to influence the situation, then we take action to influence it. We recognize that in every situation we are the only part of the equation over which we have control. Hence, when we focus on what we can do, we are inherently in a place of 100 percent responsibility and in a place of empowerment.

While it may sound like a burden to focus on what we can do, it can be incredibly freeing. By focusing on what we can do, we are suddenly freed up to act rather than waiting around for others to do so. Suddenly there is no need to passively wait for something to happen since we become initiators rather than victims.

One of the best ways to know we are in a victim/other focus mode is if we find ourselves thinking or talking about what others need to do. For example, we know we are stepping back when, in an intimate relationship, we find ourselves talking about how our partner needs to change or, in a difficult work relationship, we sit at our desk thinking about what the other person needs to do to make our relationship better. The same is true about a situation in the world or society that bothers us and we find ourselves obsessing and talking about what “they” need to do about this pressing problem.

Now of course, as was said early in the book when we discussed whether our orientation is innie or outie, the world is both. It would be good and useful for others to act—for your partner to change his or her behavior, for your work colleagues to take a hard look at themselves, and for others to take action to solve social problems. But you cannot control them. All you can do is choose to look at yourself and act accordingly.

One of the questions people often ask is, How do I get myself (or someone in my life) into a place of being an initiator rather than a victim? One of the best ways is to ask two simple questions:

• What part am I playing? (What part are you playing?)

• What can I do about it? (What can you do about it?)

These two questions can trigger game-changing shifts. Let’s say you think there is not enough romance in your relationship and you want to have more of it. As tempting as it is to make a list of actions your partner ought to take, we know we are stepping up when we ask the two questions above. How am I contributing to the lack of romance in our partnership? What actions could I take to bring more romance into the relationship? The same could be said for that difficult work relationship. We know we are stepping up when we turn the mirror on ourselves to examine our part of the difficulty and identify actions we can take.

The best way to know if you are stepping up is to become aware of the questions that are driving you. Are you asking what others need to do or focusing on what you can do? Are you asking what part others are playing or what part you can play?

The best thing about focusing on what we can do is that suddenly we feel powerful. Also, when we act, it often spurs others to act. Ironically, the best way to get others to step up is to step up ourselves! We cannot control whether anyone else decides to act, but by doing so ourselves we are reclaiming our own power and providing the best opportunity to spur change in others.

We see this even in global affairs. During the now almost two-decade effort to get humanity to cut our carbon emissions, it is not infrequent to hear people say, “What difference does it make if I act but others don’t?” I live in Canada and the United States, and people in both countries, even people in places of high influence, say, “Why does it matter if we act unless India and China act?” Though I don’t live in either of those other places, it isn’t hard to imagine people there saying, “What difference does it make if we act unless the United States does so?” In all cases, the stepping up response is to focus on what we can do as opposed to what others need to do. The truth is that because of the responsibility ripple, which was covered earlier, acting like initiators makes it more likely that others will take action.

Focusing on what we can do leans into our power. A personal example is when I first became aware of the impact plastic was having on the oceans and marine systems of the world. As a lifelong conservationist, I was deeply bothered that human garbage was destroying the ocean ecosystem and killing millions of marine birds and mammals. It would have been easier to feel and act like a victim. Yet I knew the stepping up response was to ask the questions I referenced earlier: What part am I playing, and what can I do about it?

Over a period of a year way back in 2007, I moved forward on a series of actions. First, since I live by the ocean and spend a great deal of time near it, I began making it my mission to clean up garbage on beaches that might end up in the ocean. I started posting pictures of the garbage I cleaned up on social media, asking others to do the same. Within a year I had taken a personal pledge to eliminate plastic water bottles, plastic shopping bags, and plastic straws from my life. It took some work, but soon I found that I had reduced my use of single-use plastic to close to zero. I began including plastic pollution in every keynote speech I gave, whether that was the topic of my talk or not. Eventually, much of the world started to catch on to the problem of plastic garbage, though we still have a long way to go to find sustainable solutions. While I can’t say what small role I may have helped play in that awakening, I am sure that choosing to focus on what I could do instead of what others need to do provided me with a sense of personal agency. Rather than sink into a depression, my choice to do what I was able to do gave me a sense of hope.

Speaking Up/Seeking Change or Staying Quiet/Gutting It Out

The third way we can tell, moment to moment, if we are stepping up is to see if we are speaking up or staying quiet. Another way to think of this is that when we are raising issues in a constructive way, we are taking action to move the status quo toward growth as opposed to staying silent or, even worse, moving to a place of passive aggression. The best way to think about the act of speaking up is to inquire as to whether you are asking for what you need in every situation and suggesting ways things could be different. When we stay quiet, we are often choosing not to take the risk of stepping up but to remain passive.

Here are a few examples that help illustrate this point. Let’s say there is an issue between me and a work colleague. Let’s just say the issue is that I feel my colleague dismisses my opinions and ideas without giving them consideration. Sometimes it even feels to me that this person’s behavior borders on rudeness. I feel that my colleague doesn’t demonstrate that same behavior toward others. The question is, What does it mean to step up in this situation? Let’s apply the first two behaviors. First, I must choose to be optimistic and believe that the situation can change. I must assume that through the right action we can find a place of respect. That optimism propels me toward action instead of passivity. Second, I take time to examine myself. What part might I be playing in the negative tone in the relationship, and what might I do about it? Before even raising the issue with my colleague, I take action to address the ways I may be contributing to it.

Now let’s apply the speaking up principle. By staying silent and not being clear on what I see and what I need or want, I am choosing to stay passive. Perhaps I tell other colleagues how I feel but never confront that person directly. Instead of directly speaking up, I make passive-aggressive comments in meetings such as “Well of course you don’t like that idea—because it’s not yours!” Stepping up means owning what I feel and expressing it in a way that invites others to step up as well.

Speaking up constructively is owning what I feel and the impact on me in a direct way without judgment. Speaking up in this case looks something like saying to that colleague, “I find whenever I give an opinion that I feel dismissed by you because you don’t respond to my comments at all or react only in a negative way. The impact is that I feel like you don’t respect my opinions and it has negatively affected our relationship. I am quite aware that I may be contributing to the situation as well. I’d like to find a way to improve the situation, and I am wondering how you see it.”

Dissecting that response, we see that stepping up is asking for what I need while not judging the other person’s intentions and demonstrating my desire to step up to change things. We cannot control how people respond to a genuine request for progress, but we are stepping back when we don’t honestly name something, name its impact on us, and ask for what we want.

Of course, as was discussed earlier, stepping up is also about breaking the silence. It is confrontating destructive behavior, it is challenging norms or practices at work that could harm the company, it is not remaining silent when we feel there is a better way, and most of all it is finding our voice when we could be silent. Speaking up has been found to be a powerful force in organizational effectiveness.

Listening / Learning or Being Closed-Minded/Defending

A fourth way we know we are stepping up is if we seek and openly receive feedback instead of being closed-minded or defending. One of the most important elements of 100 percent personal responsibility is to take ownership of your own improvement. The opposite of taking ownership is to receive feedback and waste energy defending ourselves against it to protect our ego.

Few things are more valuable to us than feedback, whether it is from a work colleague, an intimate partner, or even a stranger who sees us at work or elsewhere. Yet it is amazing how often our reaction is to be closed-minded and defending. Defending is the stepping back response, while being curious is the stepping up response.

Each of us needs to be aware of how we react when people give us valuable feedback for our improvement. In my experience most people receive feedback something like this: first they say thank you, and then they add a powerful stepping back word, but. That reaction is the epitome of stepping back. The but response is about going on the defensive. We usually follow the but with either an explanation (“Here is why you are not correct with your feedback”) or a defense of why we are a certain way or act in a certain way. Our reaction of defense is often not about learning but about protecting the ego. We learn nothing by protecting the ego.

So what is the stepping up response to feedback, whether it is about our work, our style, our communication, or our attitude? If you are a leader, what is the stepping up response when a team member speaks up to provide feedback about you or the organization? The 100/0 response is to be genuinely curious, to wonder what you can learn from this feedback.

When I teach people how to respond to feedback, I suggest a simple technique that has proven powerful. First say thank you in a genuine way. “Thank you for caring about my getting better.” Then say, “Tell me more.” In other words, instead of defending, get curious. Ask for examples, ask how you might improve, ask for advice, and get genuinely curious about what you might learn.

Often people say, “But what if I don’t agree with the feedback?” Well let’s say the feedback that people give you is only 10 percent correct (and I think you will agree that is rarely the case). Stepping up and owning even that 10 percent will add a lot more value to your life than defending the 90 percent. By owning the part that we need to improve, we grow our personal reputation and gain valuable insight into how we can do better.

The same is true in a company. When people raise issues, leaders must step up to be curious. We must be in a learning mode rather than a defending mode. We need to do this both because it opens us up to valuable feedback and because it makes it much more likely that people will provide feedback and ideas in the future.

One of the things I have been doing for fifteen years is that after every talk I give, I call the client a week later and ask for specific feedback on how I did, especially for areas of improvement. When I do get constructive feedback, I work hard never to defend but to express genuine curiosity. I admit that sometimes I don’t agree with the feedback, and there are times I am very tempted to defend or to explain why I did something. Sometimes I do. But when I do anything besides get curious, I know I am losing the value of learning. I know I am stepping back, not up!

Listening and learning is at the heart of ownership. In an organization, one of our greatest challenges is creating a culture where everyone is listening to customers and colleagues and leaders are listening to team members. Because I travel often, I always check Travelocity for hotel reviews. One of my pet peeves is the stepping back responses management often posts to seemingly legitimate critiques. On occasion, I see a stepping up response, where management owns what happened and assures the guests that their feedback has been heard. Sadly, this is not the norm. An organization that is truly open to feedback and takes ownership will thrive. Of course, some guests are hard to please and some are mostly wrong in their feedback, but once again we gain more by owning the 10 to 50 percent that is valid than defending our ego.

Stepping up is not just about receiving feedback with an open mind; it is about seeking it on a regular basis. It is about consistently being open to what we might learn from others and what we might learn about ourselves and our organizations by asking. Think about your own life and your own role at work and ask, Do I genuinely seek feedback? Do I genuinely respond with curiosity?

Having a Head-Up/Impact Focus or Having a Head-Down/Job Focus

The final way we know we are stepping up is if we have our head up, trying to see how we can exert influence beyond just our job. Head up means we are not just thinking about our immediate impact but thinking about our potential impact beyond whatever prescribed role or job we have. Earlier in the book we saw a few great examples of this, such as the Starbucks employees in Santa Monica who advocated for an iced coffee dessert drink, which later became the highly successful Frappuccino. Developing new products was not in their job description, but they had their heads up, thinking about how they could have an impact far beyond their role. Another example was the story of the two Canadian high school students who stood up to the bullies by getting most of the school to wear pink after a young first-year student was picked on for wearing a pink polo shirt. Once again, no one assigned them that role; they simply had their heads up, looking for how they might have an impact.

This last way of knowing when we are stepping up is most relevant in the world of work, where we often have tightly prescribed roles. When we let our job description limit us, we are stepping back. But when we decide to act beyond our job, focusing instead solely on the question of whether we can have an impact, we are stepping up. One great example of this form of stepping is the story of a frontline supervisor at a large retail liquor company. His organization had a major problem with breakage, whereby product was being broken before it could be sold, costing the organization over $2.5 million a year. Almost all the people involved had their heads down and were blaming others for the problem. The delivery people blamed the stores, the stores said it was the warehouse, and the warehouse team asserted it was the drivers. George worked in the finance department and wasn’t responsible for the breakage issue, but he took the initiative by making an appointment with the CEO. At the meeting he said, “Someone needs to solve this problem. I would like you to make it my problem.” He told the CEO he didn’t want any reward for solving the issue, nor did he even want any time off from his regular duties, he simply asked if the CEO would announce that George was going to lead a group to try to find solutions. It wasn’t in his job description, and no one assigned him this role, but he had his head up, he saw a problem outside the scope of his normal sphere of influence, and he stepped up.

Over the next several months he worked hard to get the stores, the delivery personnel, and the warehouse to work together to root out the source of the problem. Within a year breakage had been cut in half, saving the organization over $1 million of recurring revenue. He wound up getting a promotion to be the director of logistics. When the CEO retired eight years later, George was named the new CEO. But it all began when he decided not to be limited by his role and to keep his head up to look at how he could have an influence beyond his assigned place.

Having your head up is about not letting your job limit your influence, and it’s also about focusing not on your function but on the goal of the larger enterprise. I gave a great example of that earlier in the book when I wrote about the front desk employee at the Ritz-Carlton who was providing me service and observed her colleagues talking to each other while ignoring another guest. Head down behavior would have been to just “do her job,” which she was doing well. But in that moment, she had her head up, thinking about not only her success but the success of her colleagues, thinking about the impact she could have on the larger goal of the hotel to win customers and not just her guest—so she spoke up. This is head up, stepping up behavior at its best.

A similar experience happened to me when checking in at an airport. The online check in system wasn’t operational, so I had to get my boarding pass at the airport. Having arrived late for a flight I needed to be on, I was told by an agent at the check-in counter that the forty-five-minute check-in window had expired. I begged to be let on the flight to no avail. The agent at the next counter suddenly stepped aside her colleague and said, “Wait a minute. I think I know a way to check you in.” Her colleague was not necessarily impressed, but I sure was. She could have simply thought, “Not my customer [which I wasn’t], not my problem [which it wasn’t]” but she was stepping up to think about the impact for the airline and my loyalty.

Are You in the Red Zone?

One of the ways we move toward stepping up is to consistently ask which part of the continuum are we operating in at any moment—stepping up or stepping back? To our organizational clients we suggest putting the continuum on their desks so moment to moment they can make better choices. Most of us could likely take a few moments to look over that continuum and have a pretty good idea which side we are on. We saw the power of this when, over the course of several years, we designed a program for Qantas Airlines that put almost twenty thousand team members from all levels through a program on stepping up. One of the key metrics of the company’s success was its Net Promoter Score, a widely used measure within large companies that assesses customer impressions of the brand. Simply put, the score measures the percentage of customers who say they would highly recommend the company to others and is calculated by subtracting the number of people who provide a score of 0–6 (on a scale of 0–10) from those who score the company 9–10 on their likelihood to recommend it. During that period the company’s Net Promoter Scores rose significantly, and the former CEO of the domestic airline division, Lyell Strambi, said, “For the first time when we went through a crisis, it felt like management and employees were on the same page, with everyone focused on their part of the challenge.” Though we aren’t taking the lion’s share of credit for that success, I can say that one of the things that had a big impact was this simple Stepping Up Continuum.

Because Qantas’s main corporate color is red, the team members referred to the stepping up side of the continuum as being in the red and the stepping back side as being in the black. “Being in the red” became the code word for being positive, for looking at how you could take action, for speaking up in a constructive way, for listening and learning instead of defending, and for keeping your head up to see how you could take ownership of the customer experience, even if it wasn’t in your job description. All one had to say was “Let’s get in the red!” The same was true for the other side. Being in the black meant being negative, focusing on what others needed to do instead of taking action yourself, staying quiet or becoming passive-aggressive, tuning out feedback and defending, and focusing only on your function or role rather than the larger goal of providing a great customer experience.

In the end, take the time in each moment to be aware of whether you are in the red or in the black—stepping up or stepping back. You don’t necessarily have to refer to these two colors like Qantas did, but whatever code you use, be sure to use it! Of course, we won’t always stay in the red. Stepping up is about choosing to be in the red as much as you can be. Even though I teach these ideas every week, I consistently must remind myself, in real moments of action, to move toward stepping up and away from stepping back. If you want to step up more, try to imagine that each day and each moment this continuum sits on the wall and ask yourself, Was I in the red today/in this moment? How could I be more in the red tomorrow/in the next few minutes? You just might find that shift to the right makes all the difference.

Ways to Step Up

![]() Stay in the red. Put something red on your desk or in your home in a place that you will see it often. Each time you see it, remind yourself to be “in the red,” moving toward stepping up behavior.

Stay in the red. Put something red on your desk or in your home in a place that you will see it often. Each time you see it, remind yourself to be “in the red,” moving toward stepping up behavior.

![]() Focus. Choose one of the five behaviors to focus on for a period of thirty days. Over those thirty days consider that behavior at the start of your day, asking how you might embody it today. At the end of the day, review your day and ask how you embodied that behavior and how you might have done it even more so.

Focus. Choose one of the five behaviors to focus on for a period of thirty days. Over those thirty days consider that behavior at the start of your day, asking how you might embody it today. At the end of the day, review your day and ask how you embodied that behavior and how you might have done it even more so.

![]() Get some feedback. Few of us see ourselves as clearly as others do. While you may have a sense of where you need to focus for change, why not ask for some feedback? Share the five behaviors and the Stepping Up Continuum with a few trusted friends or colleagues. Then ask them where they think you are stepping up and where they think you are stepping back. As you listen to their feedback, make sure not to defend yourself but instead be curious. Practice saying, “Thank you; tell me more.”

Get some feedback. Few of us see ourselves as clearly as others do. While you may have a sense of where you need to focus for change, why not ask for some feedback? Share the five behaviors and the Stepping Up Continuum with a few trusted friends or colleagues. Then ask them where they think you are stepping up and where they think you are stepping back. As you listen to their feedback, make sure not to defend yourself but instead be curious. Practice saying, “Thank you; tell me more.”