8

Theory in Practice

Interviews and Case Studies

Since our earliest days, humans have sought new ways to express ourselves. Like language itself, our stories are one expression that have become more rich as time moved forward. Finding new ways to tell those stories has also been part of our journey of expression. Discovering new mediums, pushing them to their limits, and eventually transcending though not completely disposing of them has been the pattern that we’ve repeated over and over again with our storytelling efforts. Virtual Reality may hold the most potential of any medium that has come before it. However, it will still be subject to all the trial, error, experimentation, and eventual transcendence that its predecessors were. The speed at which this process occurs is largely dependent on us. The number of adherents and the volume of stories they choose to tell will determine the speed with which VR reaches its fullest potential as a storytelling medium, as well as the speed with which the next potentially related medium begins to show promise.

This examination of VR purposefully ends with a lengthy look at more storytellers. The most evident path for the emergence of a storytelling language in Virtual Reality will be found on the trail blazed by the early creators in the field—those doing the largest volume of and most imaginative work. Hearing what has worked and what has failed in their efforts saves us valuable time in our own experimentation. Listening to their processes, backgrounds in, and journeys toward effective and articulate communication with this medium will sharpen our own tools for creating within it. The insights of creators working within, and perhaps more importantly outside, the corners of the VR industry that we find ourselves in can expand our work in ways that don’t seem readily applicable at first glance.

Perhaps the single characteristic that unites every creator featured in these pages, besides the obvious connection to some area of VR, is the humility with which they approach the field. In nearly every interview conducted for this book, the creator was quick to state that no one has completely figured out this new language of storytelling, that all efforts thus far are simply the earliest efforts, and that the most important issue was to be aware of and learn from the efforts of everyone else creating work in this space. Holding VR storytelling somewhat loosely with an open hand was a practice this author frequently encountered. It is easy to become dogmatic about theories involving art forms. That dogma usually falls apart when the discipline of practice enters the picture. Recognizing that every story and experience in Virtual Reality should be to the benefit of the user is an ideal that should be fundamental but can easily become lost.

Style over Substance

One of the disadvantages of our rapidly advancing technological progress has been that the ability to look professional and engaging without having any real content to back up such characteristics has been put in the hands of all users, regardless of their level of expertise. This can lead to implementations of style over substance. Trailers for upcoming films promise stories packed with action, plot twists, and surprises. However, once audiences have paid for the product, they quickly discover that all that the trailer promised was actually in the trailer. The final product offered nothing more. While the novelty of VR is still fresh to many, we won’t be able to rely on the “shiny” factor for much longer. Audiences will demand more from every VR experience they engage with. If they fail to find it over a lengthy enough period, they will eventually reject the medium entirely—even if it offers an experience the user has never had before. Readers old enough to remember superior technologies such as the Betamax and DAT machine can testify to the graveyard of discarded technological mediums that has grown larger with each generation. Good stories are the best method to avoid such a fate for VR. If storytellers and VR creators are willing to invest the time in learning and executing the timeless arts of narrative, the technology stands a chance. It will be tempting to believe we already know all we need to know about story to create successful experiences. However, even the savviest of storytellers are constantly studying and developing new ways to express their characters and their journeys. In the quick progression of technology, it can be easy for well-developed and layered stories to get lost in the mix. If we believe in the power of this medium, we can’t allow this to happen.

While there are ancient elements and principles of narrative that coincide with the human psyche and will likely not change, there are other elements and principles that are constantly evolving. The ways that audiences change as they engage new media are countless. The most intuitive creators will find the ability to hold the never-changing principles of story in one hand while holding the ever-changing principles in the other. This has long been a path forward for creators in emerging media fields. Perhaps surprisingly, there is little argument about the importance of the timeless elements. There are few, if any, creators suggesting we attempt to tell stories without characters, for example. This seems to be one element, that when removed, takes away the “story-ness” from stories. The length and even structure of stories, however, has been and will be up for debate. Certain practices work in certain mediums and other practices work in others. As has been repeated, the experience of the end user and what they walk away with should drive such decisions.

Entering a Forest of Digital Trees

This examination began with the metaphor of a stone bridge covered in microchips. There is a final image and metaphor that may be helpful to consider as you move forward into telling your own stories in immersive space. Imagine a forest of digital trees. While their leaves appear to be real, they are synthetic. The green pulsing of their glow provided by the smallest of LED lights. Their stems are connected to branches of silicon. The branches are connected to trunks of reinforced steel. Beneath the surface, root-like wires wildly spread in all directions, tangling with each other and the wires of other nearby trees. There is a low hum caused by the electric soil that powers the roots and thus the trees themselves. The forest looks alive. In some ways, it even feels alive. But the life is manufactured, in a sense. Inexplicably, one day, a piece of fruit appears on a branch amid the synthetic leaves. The fruit is not digital. The fruit is organic. It is real. It is sweet and it is delicious. Day after day, more fruit appears on the trees in the forest. Some fruit rots and dies, as is the nature of living things. Other fruit remains and is enjoyed by all who enter the forest.

This, in some ways, is a picture of the field of Virtual Reality. The experiences created by storytellers in this space evoke real emotions in users. The journeys they make while immersed create feelings that are just as real as any they experience outside of the space. Amid all the technology and digital complexity, something real, organic, and meaningful emerges. Something that sparks a user’s imagination and sense of wonder. That which was never before possible suddenly appears before them in a quite realistic fashion. Opportunities arise that never existed before. Out of lifeless wires, silicon, plastic, and steel, a new reality is breathed into existence.

Interviews and Case Studies

The Storytellers

VR in a Galaxy Far, Far Away

An Interview with

Rob Bredow, Chief Technology Officer, LucasFilm

As the chief technology officer of LucasFilm, Rob Bredow oversees all technology operations for LucasFilm and Industrial Light & Magic. Bredow joined Industrial Light & Magic, a division of LucasFilm, in 2014 as a visual effects supervisor. In December 2014, he was named vice president of new media and head of LucasFilm’s Advanced Development Group. Bredow was instrumental in launching ILMxLAB in 2015, a new division that combines the talents of LucasFilm, ILM, and Skywalker Sound to develop, create, and release story-based immersive entertainment. Previously, Bredow was the CTO and visual effects supervisor at Sony Pictures Imageworks. He has worked on films such as Independence Day, Godzilla, Stuart Little, Castaway, Surf’s Up, and Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs, as well as the Star Wars VR experience, Trials on Tatooine.

| John Bucher: | I’m one of a billion people on the earth who have been a lifelong Star Wars fan. What sort of philosophical mindset does it require to take these characters that are such a core part of the culture into a new digital space with the work ILMxLAB is doing? |

| Rob Bredow: | That is one of the most fun things in my mind about getting to work at LucasFilm. If you look at the way George Lucas created and developed the world, he was embracing technology and new forms of storytelling all the time. That spirit of innovation has really just stayed alive in the studio, which has been one of the most fun things to discover as I joined—how innovative the thinking is, how fearless the crew is about trying new things, and experimenting with new forms of storytelling and technology—just to tell stories. That’s really been a part of the DNA of LucasFilm since the beginning and really holds true today. |

| John Bucher: | Can you talk about the Star Wars VR experience, Trials of Tatooine? How did the game come to be? As massive as the Star Wars universe is, how was it decided to set the game on Tatooine? |

| Rob Bredow: | Our initial creation of Trials on Tatooine was an ILMxLAB experiment. It was based on trying to get our heads around the question, “What does it feel like to be immersed in a simple story in Virtual Reality?” In our case, of course, a Star Wars story. We then would ask, “Is it fun to interact with that story when you have a first-person role in the experience?” There’s been a lot of VR done where you get to witness the story happening around you, but there’s been less VR done where you are present as a first person—present in the narrative. So what we wanted to do was find a simple, and hopefully satisfying, story that would let us experiment with what it feels like to be in Virtual Reality, and experience the story where you’re actually playing a simple role in it. |

| We had the asset, the ability to use the Millennium Falcon, because we just finished getting that working from Episode VII. We thought what would be more fun than to have the Millennium Falcon come and land right on you? Some of us have gotten to stand under the real Millennium Falcon that we built in the studio, but not many people have gotten to experience that, and no one has gotten to experience what it’s like to stand under the Millennium Falcon when it’s landing practically on your head. So that was the very beginning of the experiment. We met with Kathy Kennedy and showed her that. Skywalker Sound came in and rigged up this really amazing sound system that was probably the kind of system that you’d usually use to fill an auditorium that holds 2,000 people, and it was just all pointed at Kathy as she was experiencing the Falcon landing on Tatooine right above her. It was one of her early VR experiences, too. She took off the headset, and of course everyone is looking at her to see what she thinks, and she was like, “That’s what I’m talking about! That’s a new kind of entertainment right there!” So we had the start of something that was going to be interesting to experiment with. | |

| John Bucher: | Historically, with LucasFilm people have enjoyed the stories of Star Wars in a collective fashion—with community. We go into a movie theater and sit with a group of strangers and experience it as a group. We’ve sat in front of our televisions and watched the cartoons or the films with other people, as well. With these new experiences, we are on our own. We’re watching them in a headset where we are there with the characters by ourselves. Can you talk about the different approach of bringing someone into this more immersive environment? |

| Rob Bredow: | The kind of experiences you will see in Virtual Reality aren’t going to be solo experiences for very long. In fact, you’re already seeing a lot of work being done with multiplayer games. VR experiences will have multiple users at the same time very soon—which is going to really change the game. For this particular experiment that we did, it is a single person at a time, so we wanted to make sure the whole story was told around you so you felt like you still had social connection. You were listening to Han Solo give you instructions from the cockpit or interact with you from the Millennium Falcon, and you have other characters in the environment that you have to interact with to keep it alive and to make it as immersive as possible. |

| John Bucher: | LucasFilm is partnering with directors like Alejandro Iñárritu on new projects. Can you talk about what you’re hoping these masters of the cinematic realm are going to bring into VR space now that this new medium has started to arrive as a canvas they can work on? |

| Rob Bredow: | We’re really fortunate to get to work with people like David Goyer on the VR experience that we’re creating in xLab that will have Darth Vader in it. As you mentioned, we’re working with Alejandro on an upcoming project, as well. Our goal there is to work with some of the best creative minds in the world who are interested in building experiences in these spaces. There’s certain spaces that we can explore that happen to be the kind of projects these folks are interested in making, and we think there’s a really nice match there. So that’s really what we’re about, finding folks who have very ambitious and creative projects and experiments that need to be made and are best made in this format. These are people who can make movies or TV shows if they’d like, but there’s certain stories that may be best told in Virtual Reality or immersive experiences. |

| John Bucher: | Even though George Lucas was not the sole creator of Star Wars experiences, it seemed as though this mythological sensibility remained with LucasFilm and the projects that have been created, after he left. LucasFilm has obviously been masters at being the bridge between these universal mythological feelings we experience as human beings and the latest cutting-edge technology. How do you stay focused on being the bridge between the ancient and the cutting edge? |

| Rob Bredow: | That’s a really interesting question. There’s a huge opportunity there with Virtual Reality or Augmented Reality. For example, we’re doing a lot of work with Magic Leap right now. We know that we as people need something familiar to tie things back to—to relate the experience to. So we have those mythologies that people understand that are universal storytelling tools, and we also have this world of Star Wars that a large percentage of the world can relate to. When we put a Millennium Falcon or a droid in with you, that can be an immediate resonance that gives us a leg up when introducing someone to a new experience. You get something familiar in a way you’ve never seen it before. |

| John Bucher: | What opportunities does Augmented Reality present? What people are at that table in those creative meetings in order to come up with these ideas and execute them? |

| Rob Bredow: | It’s really a fantastic table to get to sit around and to be a small part of, because we do get to work with the best of the best. At LucasFilm, there’s this team called The Story Group that is responsible for the continuity of the Star Wars universe. We are really fortunate at xLab to have a close connection to The Story Group. They’re in all of our meetings. They help drive us creatively, which is really fantastic. All of us started at LucasFilm because we love the projects. We love this universe, so a lot of it is brainstorming the kind of stuff that we would want. We’d want these droids to be in our living room with us. We’d like to see what that’s like. What does that feel like? What can they do? What would those interaction models look like? Really it comes from a whole team of people who are Star Wars fans that want to invent these things that we want to experience ourselves. |

| John Bucher: | Is there any intentionality to connect the worlds that you’re building in the VR space at ILMxLAB and the future cinematic projects that are coming out? Will we see connections between those worlds, or will they remain different canvases that we see different stories separated on? |

| Rob Bredow: | Some of that I can’t speak to yet. The thing that I can say that’s specific to that is that we’re really fortunate to get to work really closely with the LucasFilm story groups, and they are the team that is responsible for the overall storytelling universe that we get to play in. I can’t say what specific experiences might relate to specific things in the canon, but it’s really great to have that close interaction with the team. |

| John Bucher: | Let’s talk about the idea of audiences experiencing empathy in these environments. Obviously, people have a great emotional connection to the Star Wars characters and the Star Wars universe. VR has been called the ultimate empathy machine. Do you have consultants in the science community that talk about empathy and how that’s achieved with the digital technologies, or is it more of an organic process of intuitively knowing how people will emotionally respond to this sort of content? |

| Rob Bredow: | I think our main focus is really about what a good story is in this world. The thing we’re looking for more than explicitly empathy per se is emotional resonance, which I think is slightly broader than just empathy. Empathy is great, but we’re looking for a story that has emotional resonance with the audience. And that’s often our threshold. Is this something that people would want to experience, and worth our time to build? We only get to build a tiny fraction of the total ideas we have, so we want to make sure when we’re building something, it’s going to be one of the best ideas we have. Really that vision comes from Kathy Kennedy. That’s been her mantra for the kind of projects that she expects to be made in LucasFilm. |

| John Bucher: | What makes a good Star Wars story? |

| Rob Bredow: | One of the biggest components is emotional resonance. Is there something that we universally can relate to as people? |

| John Bucher: | In Trials on Tatooine, players get an opportunity to hold a light saber and have that experience. As you mentioned, these are first-person experiences, as opposed to third-person experiences where we’re just a ghost observing these things in front of us. Can you talk about the differences in approach between something that we just observe and a story where we are the protagonist? |

| Rob Bredow: | There are quite a few differences, actually. I think the biggest one is the state that it puts the participant in. If you are just observing the things around you, you can tell very powerful stories that way, and there’s lots of stories that can be explored that way for sure. The moment you have agency in the story and you can interact with it, it really changes your overall perspective and what that story means to you, and the kind of emotions, and the impact you can have on people as they get to experience it that way. One of the experiments we did with Trials on Tatooine is to take it to a Star Wars celebration in London. That’s where a lot of fans go to get to meet the people involved in making the projects and hear about what’s coming up next. It’s a fantastic opportunity to interact with the fans firsthand. That audience was pretty excited to get to be in this world and experience what it’s like to stand under the Millennium Falcon, or to interact with R2, and of course hold a light saber. We had a lot of really positive responses and people who were very emotionally engaged in the experience. |

| John Bucher: | What would you say, on a big picture scale, would be the ideal opportunity that Virtual Reality will provide for LucasFilm? What is your ultimate hope in using these new technologies to continue to tell Star Wars stories? |

| Rob Bredow: | I think the big opportunity with Virtual Reality, or Augmented Reality, is being able to tell stories that are really well suited for this medium—that can only be told in this medium. We think there’s actually quite a few stories that are best, or perhaps only able to be told, with this sort of format. |

| John Bucher: | Will LucasFilm and ILM look through the VR lens beyond the Star Wars universe? |

| Rob Bredow: | I definitely wouldn’t rule anything out. ILMxLAB is working on projects that are outside of the Star Wars universe already because we think the Star Wars universe is a great place to tell these stories, but it’s certainly not the only one. |

| John Bucher: | You are someone who is a master storyteller that has worked for many years in these cutting-edge environments of technology. What are some of the key things that you have been able to bring from your background from working in film and special effects to the world of VR storytelling? What have been some of the key tools that you’ve continued to use with this new experience? |

| Rob Bredow: | Well, the same core emotional storytelling tools, I think, are completely applicable for cinema and Virtual Reality. I think the biggest differences are the things that have been the most interesting. I can give you a story from the making of Trials on Tatooine. |

| We had it pretty far along, and the experience was quite a lot like what you see today, but it had some extra dialogue in it. We put Kiri Hart (SVP of development at LucasFilm) through the experience, and after she came out, she said, “Give me the script, I want to make a couple suggestions.” And she did an edit on the script where she tried taking out all the dialogue that wasn’t directed right at you the user—the player. The dialogue that was happening between Han and Chewy, in the cockpit, she tried striking it out. She tried striking out pretty much anything that wasn’t happening to you directly in first person in the story. She said, “Try it without these lines and see how it feels.” Ironically, some of those lines were some of my favorite lines that Pablo (Hidalgo) and I had written, so I was like, “Oh man! That’s a super-fun line. I don’t want to cut that.” But you have to try it and see what it’s going to be like. | |

| The next day we had that version up, without those lines in it, and it was the first time that our brains completely relaxed playing Trials in Tatooine. What we learned, at least in that moment and in this phase of Virtual Reality, is if you want somebody to believe that it’s a first-person story, you can do it. But you want to continually remind them that the story is directed at them. If you are in a virtual environment where you’re already imagining you’re standing and moving in the Millennium Falcon and then the storyteller asks you to imagine that in another room, let’s say the cockpit of the Millennium Falcon, there’s another conversation going on between Han and Chewy, that’s not directed at you but instead just overhearing—it’s pretty complicated to ask somebody to pick up on it and not get distracted by it. The moment we simplified it down to be all about you, the story got that much clearer and better as a first-person experience. That’s just an example of the kind of learning and experimentation that’s happening right now at LucasFilm and ILMxLAB with our storytelling process in Virtual Reality. We’re getting surprising results. |

Acting and Directing in VR Stories

An Interview with

Tye Sheridan, Actor and Star of Ready Player One and Cocreator of Aether Inc.

Nikola Todorovic, Director and Cocreator of Aether Inc.

Tye Sheridan has been named one of Variety’s 10 Actors to Watch. Seen recently as Cyclops in X-Men: Apocalypse, Sheridan has played leading roles alongside Brad Pitt in Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life, alongside Matthew McConaughey in Mud, and portrays Wade Owen Watts/Parzival in Steven Spielberg’s Ready Player One. Nikola Todorovic is an emerging director in the world of VR with a background in visual effects. Together, Sheridan and Todorovic created Aether Inc., a VR production and development company.

| John Bucher: | Let’s start by talking about why VR has become so important. What is it about right now that, for whatever reason, makes this the right season for its large-scale adoption? |

| Tye Sheridan: | That’s a good question. I actually had a director show me a short that he did in 1998 or ’99, and it revolved around Virtual Reality where a guy had a virtual girlfriend. |

| Nikola Todorovic: | Millennials are so open to technology. When I was a kid, if you were doing something on the computer, your dad told you that you were wasting your time. Now everything is about technology. I think another reason VR is succeeding now is because the internet is faster. If you wanted to stream VR four years ago, you would have trouble. I think that’s a big issue. You have to have broadband that’s really fast to be able to do it, because everything is streaming now. People are also way more open to wearing an HMD now than they used to be. I think Google Glass was a good introduction to that, although it failed. People are still more open to wearable technology. The “Wow” factor in VR just completes that circle. |

| Tye Sheridan: | Especially for people who haven’t seen it before. I showed it to my 73-year-old grandpa and he takes the headset off, and looks at me and I said, “Well, Papa, what did you think?” He just can’t wrap his head around it and goes, “It’s different.” He just couldn’t comprehend what it actually was. It was funny to watch him inside the virtual world. I said, “Papa, you know you can look left and right and it will track wherever you look.” He starts to hesitantly turn his head left and then he realizes the frame is moving, and he can look anywhere, and it’s going to be filled by frame in a 360 environment. It was a great experience. |

| Nikola Todorovic: | I don’t like the idea that people have compared VR to 3D and its failure to be adopted en mass. 3D has existed for so long and does not really add that much to the average user’s experience. I think it’s quite different. It can’t be compared. This transforms you. It puts you in a world. It really does. We’re in such an early stage right now. This is early filmmaking. |

| John Bucher: | Chris Milk famously called VR the ultimate empathy machine. What do you think the relationship is between immersive environments and empathy? What’s the connection? |

| Tye Sheridan: | It really is a different plane of entertainment—a different experience. I remember being at Sundance 2014 and Oculus had a booth and I walked in and saw all these people trying Virtual Reality for the first time. They’d completely lost all awareness of where they were. I guess I’ve always been drawn to stories because it takes me out of my world, and this is just a totally different level of the empathy created by doing that. It’s that next level. |

| Nikola Todorovic: | I also think it’s such a psychological thing with our brains. Habituation, when our brains get used to activities, is a big problem. That’s why story is so precious. If you make a good story, you can move and inspire someone, or get someone to understand how kids in Africa live or how refugees in Syria feel. You have to make a really good story, because we see these worlds on the news all the time, and after a while, our brains become adjusted to it as normal. We can’t really feel that much empathy. Maybe for a second we’ll stop, but you see violence all the time on television. When you see someone getting killed on a TV show or a film, it really doesn’t affect you that much because you’ve seen it a thousand times, so you don’t understand how it looks and feels in real life. I think VR is so new that our brains are tricked into believing that it’s real. |

| John Bucher: | With other types of visual storytelling, be it theater, be it film, television, even video games, we experience those stories in a dark room with strangers or on the couch with family members or in an audience sitting next to people. With VR, presently, you have an HMD strapped to your head, and you’re very much alone in these environments. Can you talk a little bit about how you think the role of social VR will change storytelling? |

| Nikola Todorovic: | That’s Ready Player One, pretty much. |

| Tye Sheridan: | A much more glamorous, attractive world. You can pick and choose who you want to hang out with—the world you want to live in. Ready Player One is based on a novel by Ernest Cline, and in it, you see all of these kids who live on different planets based on their desires and likes, whether they like arcades or they like roller coasters. You can literally go to the amusement park planet or the sports planet. There are so many different options, and why would we live in a world where the limitations are restricting us from doing the things that we love to do all the time? If you can have that at your fingertips, then why not? |

| Nikola Todorovic: | Then comes the danger that I think that book speaks of so well—you can get lost. |

| Tye Sheridan: | You can totally get lost in that world. That’s one of the major themes in the story talks—staying true to reality and embracing it, because at the end of the day, it’s the only thing that’s real. |

| Nikola Todorovic: | I remember when everyone first began doing chat rooms. It changed the way we related to each other. Now, talking on the phone is getting weird, because we’re texting. You call someone that you’ve just met, they’re like, “Why is this guy calling me? Why doesn’t he text?” I think our kids are going to say, “Ha, you guys used to text. How ridiculous was that?” We lie to ourselves that it’s not moving as fast as it is. I’m not as scared about technology as many people are. I think we need to accept it. I think it will be good. There’s always the need for moderation. |

| Tye Sheridan: | I have a 16-year-old little sister, and in the past two years, I’ve seen a lot of that change represented in her life and the way she interacts with everyone and the way she’s evolved as a person. Back to Ready Player One, it touches on that a lot. It’s one of the major themes. If you get so comfortable being someone that you’re not, you start believing that you’re that person. |

| Nikola Todorovic: | I do think social VR and gaming’s going to be way bigger than entertainment VR. I think we’re going to be watching entertainment inside of these social experiences. For that reason, I don’t think people will be building avatars as often. They are just going to be themselves, I hope. |

| John Bucher: | Tye, how do you think VR is going to change the acting profession? Actors have been used to knowing, “This is my frame, and this is where I’m moving within a frame.” As that goes away, how is that going to be for actors? |

| Tye Sheridan: | That’s a great question. In recent years, I’ve become very technically aware. I believe that it allows me to do my job better when I have an awareness of what the frame is. I always ask to see the frame before I step into the shot or what lens you’re using, because when I have an awareness of the frame, it becomes clear in my mind. The easier that makes it for the cinematographer, the director, the gaffer. We can all start to work as one. We all understand each other’s job and we all understand the way the camera works and the way the set is supposed to function. With Virtual Reality, when you’re shooting in 360-degree video, it’s also super important that you stay technically aware because of issues like eye lines. It creates a new challenge for actors, but it’s also a new opportunity. In some ways, it’s more like stage acting. |

| Nikola Todorovic: | We shot a scene that was really hard recently. Someone who Tye’s character loves dearly is getting killed in front of his eyes and he cannot move. He’s tied up, so he’s screaming and crying. That’s really hard as an actor because he needs to keep that emotion going for the entire period. We can’t cut away. I think a lot of VR is going to be shot on blue or green screen for that reason. Then you will be able to do scenes like that with multiple takes. |

| Tye Sheridan: | There’s so many things to focus on. I know it’s also super difficult to direct. |

| John Bucher: | The two of you have formed this VR company. What are you hoping to bring to the VR space that will be unique? |

| Tye Sheridan: | I think there’s a huge lack of really strong narrative and story in Virtual Reality. People are getting distracted by the medium, and it is cool, but what’s the story? |

| Nikola Todorovic: | I always tell Tye, you ask yourself if you made this and put it on YouTube as a regular video, not in 360, would it be good? Story is story. It doesn’t change when you watch it on a different medium. Kids are watching multimillion-dollar movies on the iPhones. If you have a good story, it really doesn’t matter where you watch it. I think that’s one huge thing that we’re [Aether] focusing on. It’s story ahead of everything else. |

| Tye Sheridan: | Right, you can’t get distracted by the technology, just take us through the story. |

| Nikola Todorovic: | Once you call attention to the technology, I realize I’m experiencing something. I’m no longer in your story. |

| John Bucher: | It breaks the immersion. |

| Nikola Todorovic: | It totally breaks the immersion for me. I’ve seen experiences that were done in 180, and they’re great. I don’t always even need the entire 360 if the story is there. |

Case Study: Baobab VR Studios

Eric Darnell, Chief Creative Officer

Maureen Fan, Chief Executive Officer

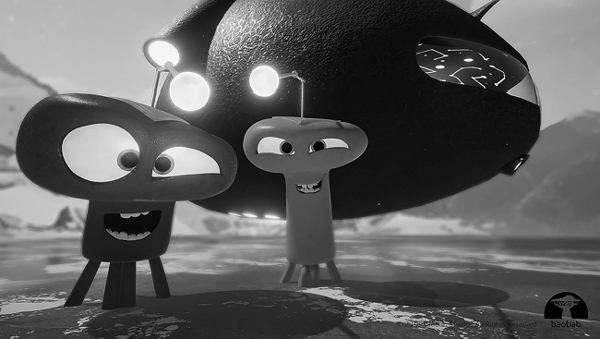

Figure 8.1 Courtesy of Baobab Studios

Figure 8.2 Courtesy of Baobab Studios

Established in 2015 by Maureen Fan and Eric Darnell, Baobab Studios is a VR animation studio, creating dynamic narratives and story lines. INVASION! was the studio’s first VR animated film, winning numerous awards including Tribeca Film Festival’s 2016 VR Selection of the Year, Cannes “Next Marche de Film,” and Toronto International Film Festival. Maureen Fan has held leadership roles in film, gaming, and the consumer web. She was vice president of games at Zynga, where she oversaw three game studios, including the FarmVille sequels. Previously, she worked on Pixar’s Toy Story and at eBay in product management and user interface (UI) design. Her most recent collaboration, The Dam Keeper, directed by Dice Tsutsumi and Robert Kondo, was nominated for the 2015 Oscar Best Animated Short.

Eric Darnell’s career spans 25 years as a computer animation director, screenwriter, story artist, film director, and executive producer. He was the director and screenwriter on all four films in the Madagascar franchise, which together have grossed more than $2.5 billion at the box office. He was also executive producer on The Penguins of Madagascar. Previously, Eric directed DreamWorks Animation’s very first animated feature film, Antz, which features the voices of Woody Allen, Gene Hackman, Christopher Walken, and Sharon Stone.

Focused on animated VR content, Fan explains why this medium has been their emphasis. “We believe that deep down inside, there’s still a dreamer inside everyone, and we know it’s true because it’s the reason that we go to the movies to this day. It’s to experience characters and stories beyond those that we meet in our common lives. And we believe that animation does this better than live action, because live action is still constrained by reality, versus animation, which is constrained only by the creativity within the director’s head. Animation, to us, it’s our emotion. It takes you to completely different worlds. It makes the world feel so real that you think you could reach out and touch it. The last two sentences that I just said, which is that it takes you to a different world and makes you believe it’s real, are the definition of Virtual Reality, which is why we think animation and VR were made for each other,” she said.

Darnell concurs. “We’re focused on interactive storytelling in Virtual Reality, and leveraging off of one of storytelling’s great strengths, which is the capacity to elicit profound, emotional experiences through the development of empathetic connections with the characters within the story. This is what storytelling has been doing for thousands of years. Storytelling has evolved with the human race. It’s in our DNA. Really, it’s what it means to be a human being, and it’s one of the reasons why these classic forms of storytelling, like literature and movies and TV and plays, can elicit these really powerful emotions in all of us. We’re talking about these powerful emotional journeys.”

Baobab has won over some of the most significant voices in visual storytelling. After seeing their content, Alvy Ray Smith, cofounder of Pixar, compared the protagonist bunny in their film to the power of VR itself. “It gives you the opportunity to believe that a character really exists, and really matters, and then be able to act on that behalf. You just can’t do that in any other storytelling medium. You know, if you look back at the movies, it’s remarkable how you can just sit in that room and it can elicit these really powerful emotional responses. It can make grown men cry, make an entire audience gasp in unison, lovers clutch others’ arms and children instinctively cry out for their mothers,” he said. Darnell agrees that story will be the key to VR’s success. “Through storytelling Virtual Reality, I believe we’ll be able to have the same kind of deep and profound emotional experiences that we have at the movies, and these experiences have the potential to be even more profound because of the fact that we’re actually living them.

“VR is not a movie. It’s not a game, at least the direction that we’re taking it. You know, there’s no camera, there’s no screen, there’s no rectangle. There’s no fourth wall to break, so when a character looks at you, they’re just looking at you. You are in their world,” he said.

Baobab plans to continue to focus its efforts around character-driven storytelling. “One thing that’s definitely true in film and certainly true in VR is that having great animated characters are always worth it. This is what storytelling is all about. It’s about connecting with these characters that you are in the world with, that you understand, not what they’re, not just what they’re doing, but you understand why they’re doing it,” Darnell said. “We need to know, we need to see what that character is thinking. Before they take an action, we all decide to take that action. We need to see that, and if you can deliver that to the audience and understand what’s driving these characters from the inside out, that’s what’s going to give you the ability to really connect with them, understand them, and empathize with them,” Darnell concluded.

Storytelling in VR through Journalism

An Interview with

Sarah Hill, CEO and Chief Storyteller, StoryUP

Sarah Hill is an Emmy-award winning, 20-year veteran of the interactive journalism industry. Before starting StoryUP, she built a successful TV feature franchise and the world’s first interactive news program based on Google Hangouts. She has produced content in Vietnam, Guatemala, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and Zambia and collaborated with companies ranging from Google to the NBA to the U.S. Army.

| John Bucher: | Tell me about how your professional interest in story began. |

| Sarah Hill: | Telling stories became important to me early on as a journalist in my fixed-frame flat world. I got into television in the early ’90s, and I did some stories about a few veterans that I fell in love with. We ended up opening up what’s called an Honor Flight Hub in Columbia, Missouri. These were flights that take aging veterans to see their memorial in Washington, DC—physical flights. I got into Virtual Reality because a lot of these veterans were calling us saying they were too ill to travel on physical flights to see the memorial in DC, so we needed an alternative. We began using Google Glass to try to take them there. We were doing live streaming tours and then we would take laptops to the veteran’s bedside. That had inherent problems with bandwidth and things like that. Someone suggested, “Have you ever heard of Virtual Reality?” |

| I tried Google Cardboard. I watched Chris Milk’s TED talk and was totally blown away. I said, “This is the missing link, this is what we can do … Use it to capture these tours for these veterans.” After we did that first experience for the veterans, I noticed they were overcome with emotion, far more than a regular fixed-frame flat video. After watching them react to immersive video content, I knew, as a storyteller, this was a very important tool that we could be using. In addition to good writing and good video, good production values, good characters, all those kinds of things—the technology of it is really ripe for storytelling to elicit an emotional response. From there, I quit my excellent job with a well-paying salary, and we opened our own company. We are an immersive media company. We have a brand studio and we have a journalism studio. | |

| Primarily, our economic engine is working with foundations and charities to try to illustrate for people their problems so that they’re able to then use that content to raise money or raise support among their donors. That’s primarily the content that we do. We also do meditation and mindfulness experiences as well. Our app features a variety of stories, not only health-care stories, but experiences about what it feels like to experience stroke. | |

| John Bucher: | Talk to me a little bit about why telling a story in VR space is different—what sort of opportunities that affords the storyteller that are different from our traditional media. |

| Sarah Hill: | It’s different, but it’s also the same. A lot of people think once they start telling stories in this sphere, “Oh this is great, there’s no frame,” and I was the same way. “Wow this is liberating. We can look anywhere,” and then you get into writing the stories and you realize, there is a frame. It’s just a frame inside the sphere and it’s moving left and right and it can be confining to the storyteller, because for decades we had the control. We were the ones who decided what they saw through that frame, and now we don’t have that control. The viewer has the control, and they have to decide where to look. As a storyteller, it’s a power struggle for us because it’s a different way of telling stories in that you don’t know what they’re seeing as opposed to what you’re seeing. You have to use positional audio. You have to use narration. You have to use graphics. You have to use tracking objects in order to gently direct the audience’s attention. |

| It’s a different way of telling stories—a different way of experiencing them. We are not experiencing them any longer through the filter of the fixed rectangle. Storytellers had used flat words and pictures and video and still photos and all these media assets to try to place people inside a story, and now the technology actually exists that we can truly put you inside the story, which is an enormously powerful tool for a storyteller. We’ve actually done studies on the difference between fixed-frame video and spherical video. There’s higher viewer engagement. It’s shared more. It’s watched longer and it’s also watched again. The reason why is that they think that they might have missed something in looking around in this sphere because they can look everywhere. | |

| Which marketers love—the fact that people would actually want to watch their content again. There’s also some very interesting things that happen in the brain between fixed-frame video and immersive video. We have a psychologist who works with us. His name is Dr. Jeff Tarrant. He’s actually studying what immersive video does to the brain, so we give him our stories to work with. People aren’t just watching the video, they’re feeling the video, and so after you create an experience, you have to put it in the faces of a variety of individuals, even the most motion-sick-prone person in the room, and say, “How’d you feel watching that? Did this slight movement bother you? At any point did you feel queasy?” | |

| John Bucher: | Let’s talk about the idea of narrative characters. We are familiar with the concept from traditional storytelling—plays and films and books. Can you talk a little bit about what you’ve brought from your traditional training and storytelling with characters and how you’ve brought that into the VR space? |

| Sarah Hill: | In journalism, we were never allowed to stage anything or use props or a set or anything like that. We just had to capture reality, and that’s what we’re really doing here with VR. You will see a lot of filmmakers who are staging or telling people what to say. Or bringing in props. And ours is more journalistic storytelling and less moviemaking. As journalists, we learned how to find compelling characters for our stories. That was what drove our stories in the fixed-frame world. It was very natural for us to be able to translate that concept into the immersive world, because when we tell stories, you can’t tell a story without a person. Sure, you can humanize around a tree or a dog or something like that, but you need characters, whether they be animate or inanimate objects. All of our stories are people driven, we call them CCCs, or central compelling characters in the story. |

| With immersive video, you really have to decide who is the camera in this scene in the story. The camera doesn’t have to be one person throughout the whole piece. We learned that the hard way. We thought, “Oh, it’s all these pieces, they have to be point-of-view pieces.” Well, they’re not, because when you do that, you don’t get all sides of the story, and sometimes you totally miss the empathy. We thought, for instance, in our Zambia piece, the point of view we should adopt is the person on the ground and we should show that view, what that’s like at all times, but if you show that at all times, you miss the very important view of what it feels like when one of these individuals was crawling towards you. You also have to have that third-person perspective as well, or your audience sometimes feels a little bit confined. Sometimes you want them to feel confined in experiences, but sometimes you really want them to experience all of those different angles. | |

| Certainly, as a journalist, our default position is that we want the audience to experience a variety of different views. To answer your question from the fixed-frame world, as a journalist, what we carried over was the ability to find compelling stories. As journalists, this was how they trained us when there was no news going on. The assignment editor would say, “Go, get out of the newsroom and find a story.” So that was what we had to become accustomed to, and if you ask any feature journalist out there right now, chances are they have about three stories in their mind that they could tell on a day when there’s nothing really going on. Why? They talk to the people at the gas station. They talk to the people at the grocery store. They’re volunteering in their communities and they’re constantly asking people, “What’s news to you?” They’re constantly thinking about stories that they could cover. | |

| John Bucher: | Let’s talk about the technical production of the pieces that you’ve done. In traditional, fixed-frame media, we’ve had the lower-third graphic that’s come up under someone. You’ve moved the lower third out into the space to put it next to the person or put it somewhere we still can identify who that person is. Can you talk a little bit about that process of finding the sweet spot of how to technically achieve good storytelling in VR? |

| Sarah Hill: | If you look at some of our early pieces, you will see that we did put it right where it’s always been in the frame, because that was where our comfort level was. We quickly realized that was not always a workable solution because viewers can look all the way around. Why have it covering the speaker’s body when it could be floating out to the side? When it could be embedded in a box that’s next to them? When it could be put in the side of a mountain? |

| John Bucher: | Can you tell us a little bit about where you’re taking this and where you want to see VR storytelling go? |

| Sarah Hill: | We have a project coming out with Empowered By Light and the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation, and it’s all about solar energy—how a lack of solar energy threatens to flood sacred lands of a certain tribe in the Amazon. These sorts of projects that make the world a better place are where I’d like to continue seeing us go. We’re also shooting a project with Facebook and Oculus and a charity called Love Has No Labels. We’re playing with cropping. We’re playing with the sphere. We’re playing with mirrors. We are looking at implicit bias, using 360-degree video to illustrate for people our implicit bias, and how if we’re only seeing this much of a story or of a person, we’re not seeing their whole picture. We’re not seeing them fully, and we don’t have enough information to judge that situation fully. |

| John Bucher: | Finally, all technology takes us somewhere. It transports us somewhere. Where, in an ideal world, would you love to see this technology transport humanity? |

| Sarah Hill: | I would like it to transport us back to our home videos. I want the ability to put my fixed-frame video of my second birthday with my mom in a VR headset and watch it again like I was there. I know that some smart person will come up with that idea, but I think that would be really great to see. |

Insights from the Storytellers

Storytellers provide looks at life that range from our own backyards to the farthest reaches of outer space. The tools at their disposal are advancing faster than ever. Some storytellers work with characters and archetypes very familiar to their audiences, like Rob Bredow. Others, such as Sarah Hill, are making the decision of what real-life personalities will be the characters in the story with every project. Both storytellers use characters, but in completely different ways. Understanding how characters work, as discussed in detail in Chapter 6, helps creators identify one of the most basic building blocks of narrative. We feel empathy for characters and the situations they find themselves in, not for environments or lifeless objects, such as costumes, important as those elements are. Bredow more specifically identifies emotional resonance as the sort of empathy he looks for in creating stories. Resonance suggests that two similar things share qualities. Emotional resonance would then speak to two individuals sharing qualities or emotions—the character and the audience member. Hill referred to these as the three Cs—central compelling characters. These are just the sorts of characters Tye Sheridan embodies when telling stories in VR. He models what is possible when an actor truly understands their role in the storytelling process. There’s no need for us to consider or move on to storytelling structure if we don’t have compelling characters in place.

While Baobab uses primarily animated animals in their stories, they demonstrate the same understanding of characters. They value the same empathy and emotional resonance that Bredow speaks of. There is a wide span between the sorts of stories told by Sarah Hill in Africa, Baobab in animation, and Rob Bredow in the Star Wars universe, and yet there is not. All the storytellers in this section understand that story begins with effective characters that people can identify with. All understand the power and even limits of the technology they are using but don’t let that become the focus of their work. They create characters that embody the best (and worst) of who we are and who we want to be. We learn lessons from the characters’ mistakes and take joy in their victories. Stories that are true, loosely based on real events, and completely fictional all have a place in the narrative universe, and certainly in the world of VR, as long as they hold the tenets of storytelling that have served humankind for thousands of years—characters, conflicts, and resolutions.

A number of storytellers in this section and in this book mention that VR will not be experienced by only a single person at a time for much longer. As social VR experience becomes available, the emotional resonance experienced through the technology will be held by an entire audience together, much as it is in a movie theater. Social VR experiences and stories will hold the capability to engage the smallest audiences of two or three, as well as the capability to tell stories to literally thousands of people at one time. These potentials will undoubtedly change the ways stories are crafted in VR space as they develop. These changes will make it increasingly important to rely on and implement the elements and methods that have seemed to work across centuries and mediums. As Eric Darnell stated, “Storytelling has evolved with the human race. It’s in our DNA.” There’s been no indication it will not serve us in all the same ways it has throughout our evolution.

The Technologists and Producers

Nonlinear Storytelling in VR

An Interview with

Jonathan Krusell, Google Daydream Producer

Jonathan Krusell is a creator with more than ten years of experience leading production, creative, and strategy for interactive entertainment. His career has included roles ranging from VP of production to studio director. Awards for some of the games he has worked on include IGN People’s Choice Award 2012 (Avengers Initiative), Best Family Game at E3 2009 (Disney’s Guilty Party), and GameSpot Best Use of Zombies at E3 2005 (Stubbs the Zombie). Other significant properties he has worked on include Disney’s The Haunted Mansion, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, 50 Cent Bulletproof: G Unit Edition, and Spiderman 3. Currently, he serves as an executive producer at Mindshow and a producer for Google’s Daydream.

| John Bucher: | Tell me about your background in gaming and how that led to VR. |

| Jonathan Krusell: | I’ve been doing games for 15 years—console, PC, and mobile. Games are what I set out to do, actually. I went to film school, was interested in movies, but to me, I felt like movies had peaked in the late ’70s. I don’t know if I was right about that, but I wanted to get into something that was still on the rise, so games are where I was focused for a long time. The thing that I find interesting about VR is that previously in games, the user is pointing things into a controller, the controller takes those signals, puts it into a system, the system interprets that and then triggers animations, right? If you think of the player as a performer and the avatar as the presentation of that performance, there’s a lot of layers between them. A lot of those layers collapse now with VR. On the high-end systems, and even the medium-level systems in VR, you basically have consumer-grade motion-capture systems. The HTC Vive has the lighthouses that capture your motion. Oculus has cameras. Daydream has accelerometers. They’re all capturing motion, but it’s actually your motion. |

| Some games let the player directly drive the characters. That means that all those layers have collapsed now. What that means is that there’s this opportunity now for improvisation. You can do things that no engineer ever thought of. Previously, engineers, designers, and artists had to think about everything ahead of time and invest it all into the software so that you could trigger it. They don’t have to do that anymore. You can’t do everything yet, because it’s not full-body mocap, but it’s still pretty robust. In the near future, it will get more and more robust as newer technologies develop and converge. Things like that exist right now, but just on separate devices. As those things come together into a single device, it will be more and more robust. | |

| John Bucher: | What were you able to bring over from the gaming world that works well in VR? What did you have to transcend? |

| Jonathan Krusell: | The biggest thing I think I bring to VR is just a stomach for software development. Software development is a very nerve-racking thing. Things are constantly evolving, and it’s hard to predict where it’s all going to end out. The first three times you work on developing a project, it’s terrifying. Eventually you get a stomach for it and you’re like, “Okay. Everything’s probably going to be okay.” I’m also comfortable with nonlinear storytelling. Actually, I’m super comfortable with it and prefer it to a three-act structure. A three-act-structure story means you’re taking agency away from the user. Video games tried to do that for so long with movie audiences. We were just trying to recreate a movie in a game. Nonlinear storytelling has served me very well in VR. I used to run a motion-capture studio. Similar to a theater in the round. We were constantly thinking about 3D volumes and 3D spaces and thinking about storytelling where you don’t know where the user is. Half-Life’s always done that really well. There’s a narrative happening with dialogue that’s preprogrammed, but you can move throughout the space and they react to you. On top of all that, I love the idea of immersion—trying to find ways to get the player to be engrossed in the experience. Not many other mediums have immersion at the level VR does. Books are the most immersive thing in the world, but they’re a particular medium that doesn’t include an audio/video experience or haptic feedback. |

| John Bucher: | In VR, we have a deeper level of embodiment. In some VR experiences, I can look and actually see my hands. Can you talk about embodiment? |

| Jonathan Krusell: | That’s something that is actually different from video games. The tropes that I’m used to from games—they’re evolving. They don’t apply the way they used to, whereas a third-person action game previously felt like you were driving an avatar, right. But now, a third-person experience in VR feels like me and you. There’s a character, and I’m a different character, and we’re working together to do something. That’s very different. |

| First person is even more different. Previously, first person felt like I was in the action, but there was a barrier between me and the world—the screen. But now with VR, that barrier is dissolved and I am actually surrounded by it. It can be jarring and shocking for some users. As a designer, you have to ask, how uncomfortable are you willing to make the user, and does that become a barrier to other things you’re trying to accomplish? | |

| With some of the applications I’ve worked on, you could embody an alien, or you could embody a woman, or you could embody a man with completely different proportions, right. In all those cases, there’s going to be moments of, minutes of, or never-ending discomfort. Female characters in video games are super popular. But I wonder if in VR it will be a bigger barrier for some males—to embody a female character and get comfortable with that. You have to be thoughtful about when and how you’re going to do it and also to prepare the user for it. It can be jarring to suddenly be in a new space and have a little micro–identity crisis about what’s going on. That’s one area where it is very different than games, and there is still lots to figure out and learn about. | |

| John Bucher: | You have developed content for Disney before. We often think about VR as being something that people 16 and up really engage with, maybe 16 to 40, actually, being the target demographic. When we think about putting a headset on children, do you think there are going to be different ways that we approach VR for different-age audiences? Obviously, content is going to be an issue, but do you think there will be differences in how we design or tell stories? |

| Jonathan Krusell: | Yes. I think there’s different ways that you would consider the ideal-use case—thinking through session length and intensity. I think Google Cardboard is something that is okay for a ten-year-old, because it’s not as intense. It’s something that’s easy to remove. It’s something that’s made with short sessions in mind. I think Expeditions is a great example of how you can make content that is only doable in VR—taking big field trips together. My kids are pretty young. I hesitate to put them in any VR, but I certainly wouldn’t put them in an HTC Vive, because it’s just too intense. I had a weird experience showing my mother VR. She’s over 70. I didn’t realize until it was on her how ridiculous it all looked because the Vive looks like you’re piloting a drone or something. It looks military grade. |

| John Bucher: | What do you think are going to be the ongoing challenges that storytellers in VR will continue to grapple with? |

| Jonathan Krusell: | When you’re in software development, the thing is that you never get comfortable. The technology’s always changing. You have to get used to that sort of cadence. I think that’s going to be challenging for people coming from other industries that are now learning the ins and outs of software development. At some point, there’s going to be some pretty big moral content decisions. Right now, it’s a pretty tight-knit community, and there’s some unspoken territory to stay away from. It’s not going to be like that forever. |

| John Bucher: | If I become comfortable having the experience of killing a very human AI, I’ve experienced the feeling of murder. What do you think are the ethical issues that we would do well to think about now? Most people agree, you can play video games and you can shoot people all day, and you’re not going to really want to go kill a human being. But at some point, with artificial intelligence in Virtual Reality, you’re going to feel like you’ve actually shot someone. How do we navigate it? |

| Jonathan Krusell: | Yeah, I agree with you. In the past, there was the barrier of the screen that arguably made everybody realize it was fantasy. That doesn’t exist anymore. How do we regulate that? I don’t know. How do current channels with lots of power self-regulate? Because, ideally, there’s some sort of system that self-regulates. I can’t immediately think of a system like that that works well. These are important questions to ask because they’re inevitable. |

| John Bucher: | I want to circle back to nonlinear storytelling. It can be argued that with all of human activity, we make sense of the world through narratives. |

| Jonathan Krusell: | We layer story on it, constantly. |

| John Bucher: | Absolutely. When we talk about nonlinear storytelling, are there narrative shards that we pull from a structured story where we say, “Well, it’s not a linear story, but we still have a good guy and a bad guy, or we still have this conflict”? How does nonlinear storytelling work? Can you tease out that a bit? |

| Jonathan Krusell: | There’s different kinds of nonlinear storytelling. If you think of the film, Clue, it has multiple endings. So does the board game. Nonlinear works well in the mystery genre. Where the board game Clue is simply context and progression, there’s the context of a game board, and there’s a context of the clues and the characters, and then there’s the progression as you move through and make your own deductions. The game doesn’t know what choices you’re going to make. The game doesn’t tell you how to perceive the clues that you find and make the deductions that you make. Now, the game does know who is actually guilty. It’s in the envelope. That doesn’t change the story that you’re telling. |

| It’s all nonlinear until the end, because the ending is decided. But you’re able to create your own story in your head by the breadcrumbs that you pick up and how you interpret them. To me, that is nonlinear storytelling, which is like context plus progression, having choice in the matter, and being able to interpret and deduce what you believe. That’s what I think I’m really excited about in VR is the idea of mystery games. When you talk about Alternative Reality games, the murder mystery is the oldest Alternative Reality game there is. | |

| John Bucher: | In video games, most stories have an end—you can conquer the game. There’s exceptions—world-building games that just go on and on. Do you see, with VR experiences, somebody entering a space where there’s not a clear ending or objective? Do you think that’s going to get frustrating for people, or do you think just being able to constantly explore will have the same effect as, say, a World of Warcraft that can just go on forever? What do you think we need to be designing experiences toward? Do we need to guide people towards an ending or just endless exploration? |

| Jonathan Krusell: | Well, I think it’s going to evolve as the medium evolves. I think, right now, an ending is fine. I think right now there’s going to be a lot of single-player experiences that are finite in length, maybe even episodic. These are all experiments right now, to learn about what is ideal. Then as it evolves, it can go in any number of directions. I definitely think that multiplayer or shared experiences are going to be huge. I think that taking on different characters, like in a murder mystery, where there is improvisation, will be effective. Let’s do it in a castle. No, let’s do it in a Victorian manor. That sort of thing, that allows people to customize the experience for themselves. Then, ultimately, I do think that these things would exist in some sort of shared universe where it’s looped within loops. Where you complete one loop and it just reveals a bigger loop. Which is just basically creating some sort of simulated reality. But a simulated reality would define rules. What matters the most, though, is what the promise is to the user when they’re going into it. Is there promise of an ending? Well, then you better give them an ending. Or is the promise a universe? In which case, you have to establish the rules and then let them make whatever choice they want within those rules. That’s where the real potential is—shared universes. |

| John Bucher: | Do you think rules are going to be necessary in order to ground Virtual Reality and cause people to actually have a truly immersive experience? |

| Jonathan Krusell: | I think rules are inherent. That’s why if you make something look photo-realistic, then you are setting a bar that everything else has to match, so the physics better be realistic, the lighting better be realistic, and the rule set better be realistic. Whereas if you make something that looks like VR Super Mario, then it’s a totally different rule set. |

| I think it’s not a question of do we have to create a rule set; people expect rule sets and they take in what they see and they make rules already. They try to figure out what the rule set is in a scenario, and hopefully you meet that expectation. If you make a decision to dramatically surprise them with a rule they didn’t expect, that’s a risky move, because it could blow away immersion. If something did look photo-realistic, but then I couldn’t pick it up, I’m upset. In video games, you get away with that stuff because the expectations are different. You get away with a lot of things in video games that I don’t think you can get away with in VR. You have to be very deliberate. That’s why for right now, stylized content is a little safer, because then you can communicate the rules to the player as you go. I like starting small and then layering complexity on top of it. That’s just my style, because I think you can get to something more consistent that way. | |

| John Bucher: | You brought up multiplayer experiences. In the history of VR, it’s been a very singular experience thus far. I put on the glasses and I’m alone. I’m figuring this all out myself. That will obviously change in the near future as we begin to have these multiplayer experiences with friends or family or strangers. How does storytelling change when we go from a medium for individuals to a group dynamic? |

| Jonathan Krusell: | I think it’s going to be like LARPing—where we all agree to live in this fantasy and we do our best to support each other in that fantasy, and if you break it, there’s some sort of social repercussion for that. I mean, we’re all doing that right now, every moment, in real life. It’s just not as fantastical. The trick with the VR, though, is going to be matchmaking—which is a really big deal. You have to have a critical mass of players at a certain time, at a variety of skill levels, that you can set up quality matches where everyone has fun, and then they show up again later. That’s how things are with console games. |

| Now in VR, at least in my opinion of the immediate future, you’re looking at drastically shorter sessions—like an hour or less. How do you reach critical mass so that you can have a quality multiplayer experience? It’s tricky. It has to be very event driven. It has to be super event driven where there’s a reason. It’s like now with Netflix and all this streaming media where you can consume anything at any time. Now there might be this new VR event system where it becomes water-cooler talk. “Oh man, were you there last night?” | |

| There’s two things that are exciting, to me. There’s the shared fantasy, and then there’s the creation tools. I am intrigued by shared fantasy—role-playing. Then things like Google’s Tilt Brush that allow you to create in a way that you can only do in VR. If you can combine those two things, that’s the magic. | |

| John Bucher: | Can you speak about what VR could look like as a storytelling medium once we are able to get away from the HMDs? Once it becomes truly augmented reality across the board, what is storytelling like then, and how thin does that line get between narratives and just actual reality? |

| Jonathan Krusell: | There’ll have to be some sort of visual language or some sort of adaptive density of fantasy where it can figure out the mental state you’re in and dial it in to what you need at that moment. When the technology is that seamless, it’s going to get real weird. Is there some sort of centralized service that is making sure that we’re all not in conflict, like our fantasies are harmonious, or at least reinforce each other? That we don’t walk off cliffs or something like that? I think that barring any extinction-level events, it will eventually get there, and that’s where we’ll need AI to help out a lot, if they don’t enslave us first. |

Horror-Based Storytelling in VR

An Interview with

Robyn Tong Gray, COO and Lead Designer, Otherworld Interactive

Andrew Goldstein, CEO, Otherworld Interactive

Robyn Tong Gray is an interactive media designer who weaves new media together to explore narrative and empathy. Her projects have been featured at venues including the Independent Games Festival, IndieCade, and the Sundance Film Festival. Robyn is the director of Sisters, Otherworld Interactive’s horror franchise revolving around a pair of spooky twin dolls and their haunted home. She and Andrew Goldstein founded Otherworld Interactive, a Virtual Reality content studio located in Culver City, CA. Their company has been featured in publications across the industry, including a significant profile in PC Magazine.

| John Bucher: | How did you become interested in VR? What brought you into immersive space? |

| Robyn Tong Gray: | Andy and I both finished our graduate degrees over at USC’s Interactive Media Program. They have a really high concentration of professors who came out of VR. When we were there, Mark Bolas was still on faculty. He’s now working on the Hollow Lens at Microsoft. We also met Scott Fisher. Both of these guys worked at NASA on some of the first early, practical VR in the 1980s. |

| When I first started in the program at USC, I was a research assistant at the Mixed Reality Lab, which, at the time, Mark Bolas was the director of. I loved storytelling in all mediums. Interactive is particularly fascinating to me. Game markets were flooded, but there’s this whole new thing with all these new opportunities to actually make something that people will see and has a chance of standing out—and that was VR. | |

| Andrew Goldstein: | Robyn had been making some Virtual Reality projects and had a lot of knowledge there and looped me in, saying, let’s see if we can push this forward and start a business. It was great because, at the time, we were one of the few people out there making VR, and we basically have rolled that into a company. |

| John Bucher: | Let’s talk about your most successful horror project, Sisters. How did that project come to be? |

| Robyn Tong Gray: | Sisters was originally a two-week project. I love horror movies, and obviously, VR is a lot about tapping into players’ gut reactions—something horror excels at. So we thought, why not make something spooky? I would say with Sisters we play a lot with tropes. We’re not really treading new ground when it comes to the scares there, but I think that’s actually important right now in VR—to make people understand that this is something they are familiar with on some level. Even if they don’t recognize the media they’ve suddenly been placed in. |

| John Bucher: | Did your classic story training and the storytelling tropes you mentioned translate well to VR? |

| Robyn Tong Gray: | I think it translated really well. With Sisters, it was taking a lot of the stuff you learned about when you make games. A lot about indirect control and then also a lot more pushing audio, for example, which is often ignored in games. I came up with the script really early on. I decided the interest curve we want, and that we don’t want to have too many plateaus in there where people lose interest. I think from there, it was mainly fine-tuning things, figuring out a good distance for the dolls to pop up from, the timing, and things like that. Also, playing around with jump scares. I love jump scares. They are really easy and cheap, but I love them. We also wanted to move beyond jump scares to incorporate details that might tell a little bit more about the story and that might give you a hint that there’s something beyond this two-minute, linear narrative. |

| John Bucher: | Let’s talk about the idea of agency in VR. It’s one of the things everyone is trying to figure out—what’s the perfect mix of giving the viewer a sense of local agency as opposed to giving a sense of global agency? Do people want to make the small decisions of figuring out what weapon they are going to be able to carry, or do they want to make the decisions that drive the entire narrative? Are you having those sorts of discussions in the things that you’re designing? |

| Robyn Tong Gray: | We’ve taken a lot of what we’ve worked on so far from the traditional gaming world. We are asking if we want to make branching narratives. Do we want to make this linear? As a player, I always want to feel like I have these awesome choices that I’m really going to affect the world that the story’s taking place in. On the flip side of that, I feel like nothing I’ve seen has done that in a way that makes me really satisfied about it in VR yet. I think it’s often to the detriment of the story at the moment. |

| Even with The Walking Dead experience by Telltale. They really tapped into people’s empathy, really made you feel like you were struggling for these choices, but if you play it a second time around, you feel like nothing you decided on mattered because the other people got axed later. That’s horribly dissatisfying. Clearly, there was a story there that whoever made it really wanted to tell, and anything that diverted from that main vision didn’t feel great as a result. For us, we’ve been setting tone for this global story. We want the players to feel agency in that. They might not be able to alter the huge overarching fate of the world, but they can make decisions for themselves that feel good and feel like they did the best they could, just like in real life under those circumstances. | |

| Andrew Goldstein: | Robyn brings up a really important point that Virtual Reality is about environmental storytelling. It’s not always about linear storytelling. Your job as a Virtual Reality creator is not always to create the best linear story possible. That’s sometimes the job of the film the experience is based on. Sometimes, our task is to create the best environment possible that adds to that story. A lot of times we reference things you embed in the environment that may be interactive, that you might catch, but add a slight level to you being in the space. They’re not necessarily linear pieces, but they add to the overall ambiance of being there. |

| It’s creating a new language and new canon for the media. That’s where I think a lot of people don’t quite understand that Virtual Reality is not the next step in film or the next step in games. It’s its own separate thing, and we’re still tinkering with how to make it good. Specifically, with that, there are genres in Virtual Reality that play much better than other genres. Horror, sci-fi, stuff that’s really heavy on being there to understand it does so much better than comedy and drama. People who initially start out trying to do comedy have a lot tougher goal getting something out there because comedy is really specific with timing, or else you kind of miss it, whereas horror is completely ambiance. It’s about feeling scared. | |

| John Bucher: | Let’s talk more about challenges. For several years, people have said the biggest challenge to VR storytelling were things like frame rates or latency—those types of technical challenges, which certainly still exist. But aside from the obvious technical challenges, what are you finding are the biggest hills to overcome? |

| Robyn Tong Gray: | I think it’s really about setting expectations. With a lot of traditional, say, inventor games, you have the expectation very quickly knowing that something’s purple, which means you can interact with it. You can grab it. Other things are not purple, so you can just ignore them. With VR, you’re putting people in this place, and if you’ve done it really well, then their expectations will be that everything is interactive in the world. |