3

Types of Strategy

Which Fits Your Business?

Key Topics Covered in This Chapter

- Low-cost leadership strategy, and how to make it work

- Differentiating a product or service—even a commodity—in ways that create real value for customers

- Customer relationship strategy, and six approaches for making it valuable for customers

- The network effect strategy: winner-take-all

- Determining which strategic approach is right for you

LOOK AT THE many textbooks on business strategy and you’ll find a cornucopia of strategy frameworks: low-cost leadership, diversification, merger-acquisition, global, customer focus, product leadership, vertical integration, flexibility, product/service differentiation, and so forth. What are these strategies? And now that you understand the external environment and your internal strengths and weaknesses, how can you determine which is best and most appropriate for your company?

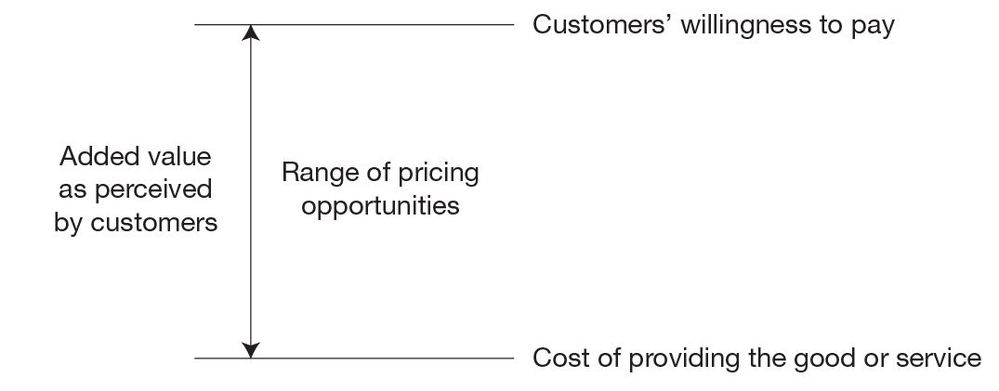

At bottom, every for-profit entity aims for the same goal: to identify and pursue a strategy that will give it a defensible and profitable hold on some segment of the marketplace. That segment, by choice, may be large or small. It may produce, by choice, high profits on a small number of transactions, or low profits on every one of millions of sales. It may involve superficial relationships with many customers or long-term and deep relationships with just a few. No matter which strategies they follow, these companies will also try to increase the range of profitability—that is, the difference between what customers are willing to pay and the company’s cost of providing its goods or services.

This chapter describes four basic strategies: low-cost leadership, product/service differentiation, customer relationship, and network effect. It is difficult to find a business strategy that is not one of these or some variation.

Low-Cost Leadership

Low-cost leadership has paved the road to success for many companies. Discount retailers in the United States such as E.J. Korvette and later Kmart grabbed significant chunks of the retail market away from traditional department stores and specialty stores when they first appeared in the 1950s and 1960s. Their success was a function of their ability to deliver goods at lower prices; and they developed that ability by keeping their cost structures much lower than those of traditional competitors. These early discounters were displaced, in turn, by Wal-Mart and Target, which were even more effective in operating a low-cost strategy.

In this strategy, the product or service is usually the same as the product or service offered by rivals. It may be a commodity, such as rolled steel or household electrical wire, or it may be something readily available through other vendors. Items sold by Wal-Mart, for example, can be obtained at many other locations, some just down the street—Duracell batteries, Minolta binoculars, Canon cameras, Kodak photographic film, Wrangler jeans, Hanes underwear, Gillette razor blades, Bic pens. So why do so many people in North America head to Wal-Mart and Target to buy these items, often driving past rival vendor locations? Because they believe they will get the same items for less money. And they usually do. Wal-Mart in particular was built with this low-cost advantage as a key part of its overall strategy.

The key to success using the low-cost strategy is to deliver the customer’s expected level of value at a cost that assures an adequate level of profitability. Consider figure 3-1, which is adapted from a model first advanced by Adam Brandenburger and Harborne Stuart. The vertical distance between the willingness of customers to pay (top line) and the cost of providing the product itself (bottom line) represents the range of pricing within which every company must operate. It also represents the value added by the company, as perceived by customers. For commodity-like or undifferentiated products, the spread between these lines is narrow. And the top line—what customers are willing to pay—is generally fixed. So, to establish greater profitability, the vendor must push the cost-of-providing line lower. It will generally attempt to do this through operational efficiency, pressuring suppliers for low prices, and other means. This is the game that Wal-Mart has been playing and winning for many years. It has squeezed more costs out of its supply chain than has any other major retailer.

Expected Value

It’s easy to assume that the low-cost leadership strategy applies solely to physical products: jeans, paint, tons of steel, and so forth. There are, however, many examples of low-cost strategy in the service sector. Consider The Vanguard Group, a leading investment management company. Started in 1975, the company provides a broad array of mutual funds and a very high level of client service. There is nothing particularly fancy about Vanguard or its funds. While some of its actively managed funds have been top performers over the long term, many are index funds that purposely aim to replicate the return of the market, not “beat” it. In most years, these passive index funds actually outperform the average managed fund.

What really sets Vanguard apart from other fund families is its no-commission policy and the fact that it has the lowest average expense ratio among fund families. In 2003, for example, Vanguard’s average expense ratio was a tiny 0.25 percent of assets—less than one-fifth of the mutual fund industry’s average expense ratio of 1.38 percent. That has the effect of giving Vanguard clients a 1.13 percent greater annual return on their money (all else being equal). By keeping management and transaction costs low, Vanguard actually invests and reinvests more of a client’s money. And that produces better returns over time. Vanguard’s success with this strategy has earned it accolades among individual investors and made it one of the largest fund families in the United States.

Making the Low-Cost Strategy Work

As mentioned above, the key to retaining low-cost leadership is keeping the costs of providing goods or services lower than those of competitors. This is a constant challenge, since rivals will be working hard to drive their costs lower than yours. But it can be achieved through several means. Consider these four:

CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT IN OPERATING EFFICIENCY. The Japanese developed the philosophy of kaizen, or continuous process improvement, to gain their well-known lead in manufacturing. Kaizen encourages everyone, from the executive suite to the loading dock, to seek out ways to incrementally improve what they are doing. A 1 percent improvement here and a 2 percent improvement there quickly add up over time, giving the firm a notable cost advantage. The concept of process reengineering aims for a similar result, but kaizen aims for incremental improvements to the existing work, whereas process engineering aims for large breakthrough change—either through wholesale restructuring or the total elimination of existing activities. Both kaizen and process engineering have had profound impacts of operating efficiency in both manufacturing and services.

EXPLOITATION OF THE EXPERIENCE CURVE. Production managers know that people learn to do the same job more quickly and with fewer errors the more frequently they do the job. Thus, a heart operation that once took eight hours to complete can be done successfully in four hours as a surgical team gains more and more experience with the procedure. And before long, they may have it done in two or three hours. The same is observed in manufacturing settings in which managers and employees focus on learning.

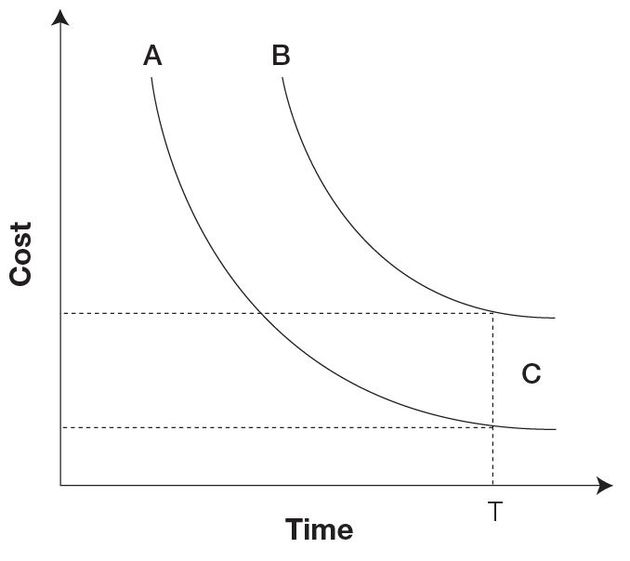

The experience curve concept holds that the cost of doing a repetitive task decreases by some percentage each time the cumulative volume of production doubles. Thus, a company that gets onto the experience curve sooner than an imitator can theoretically maintain a cost advantage. Consider the two cost curves in figure 3-2. Both companies A and B begin at the same cost level and learn at the same rate. They compete primarily on price. But A got into the business first and, consequently, is further down the cost curve than rival B, maintaining its cost advantage at every point in time. At time T, for instance, that advantage is C. Company B must either learn at a much faster rate, accept a permanent cost disadvantage (and smaller profit margin), or exit the market.

AN UNBEATABLE SUPPLY CHAIN. Everyone is familiar with the Dell business model. It sells its PCs directly to consumers, skipping the middleman. It also builds those PCs to order, thus eliminating the costly finished goods inventory problem that plagues rivals that operate with traditional business models. It has no finished products sitting on the shelf and becoming more and more technically obsolete by the day.

The Experience Curve

What people often overlook about Dell is the efficiency and effectiveness of its supply chain. That chain includes component suppliers, assemblers, and the logistical services of United Parcel Service. All are digitally linked so that order information can be immediately translated into production and delivery schedules. The ability of this supply chain to deliver a customized PC to a customer’s doorstep in a week or so makes it possible to eliminate middlemen and inventory costs, giving the company cost leadership in its field. Wal-Mart provides yet another example of a company that commands cost leadership through the power of its supply chain.

PRODUCT REDESIGN. Huge cost reductions are often achieved through product redesign. For example, back in the 1970s, Black & Decker, a manufacturer of consumer power tools, found itself going head-to-head with low-cost Asian competitors. It had a serious cost disadvantage that could not be cured by simply being more thrifty and efficient. Something more dramatic was required. B&D responded by redesigning its entire family of consumer power tools and the process for making them. At the heart of its product line makeover was a single electric motor that could be inexpensively altered to provide power for any number of different hand tools. That eliminated dozens of different motor types as well as the need to make and store hundreds of different components. The core product platform’s simplicity and “manufacturability” made it possible to produce the new family of tools with 85 percent lower labor costs. Inventory and other related costs tumbled by similar percentages. The Société Micromécanique et Horlogère (Swiss Corporation for Microelectronics and Watchmaking Industries Ltd.) accomplished similar results with its development of the Swatch watch, which was based on the company’s development of a reliable, plastic, quartz timekeeper that could be mass-produced for a tiny fraction of the cost of traditional watchworks. This design breakthrough made it possible for the Swiss company to compete and prosper in a market dominated by low-cost Asian competitors.

In these and other cases, product redesign proved to be an effective tool for achieving cost leadership.

Operational excellence is an important part of low-cost leadership strategy, but only a part. As we’ll see later, becoming the low-cost leader involves more than pinching pennies and squeezing the fat out of business processes. Above all it entails a thoughtful plan for structuring the enterprise. Consider this analogy: If you want to be the fastest sailboat in your area, you don’t simply wax the hull and train your crew to get the most out of the floating bathtub you call your boat—instead, you build a craft that is designed for speed from the keel up. The business equivalent is to structure the organization to deliver low-cost leadership.

Is a low-cost strategy feasible for your company? If it is, what would have to happen to make it work?

Differentiation

Every successful strategy is about differentiation, even the low-cost leadership strategy. “We can fly you to Genoa for less than our competitors.” “At Auto City Sales, we will not be undersold.” But for most companies, differentiation is expressed in some qualitative way that customers value. For example, when Thomas Edison first began to market his system of electric incandescent lighting, his principal rivals were local gas companies. Both methods of illumination were effective, but Edison’s approach had clear differences that most customers favored. Unlike gas lamps, electric lighting didn’t noticeably heat up people’s living rooms on hot summer nights. It was more convenient, requiring just a flick of the switch to turn it on and off. And it eliminated a serious fire hazard in many applications. Edison played on these qualitative differences as he attacked and eliminated the gas companies’ dominance of urban lighting in the late 1800s.

Companies today likewise adopt differentiation strategies. Consider the auto industry. Volvo touts the crashworthiness of its vehicles to set itself apart. Toyota plays on its reputation for quality and high resale value; more recently it has differentiated its Prius model with hybrid engine technology. The Mini Cooper practically screams “I’m fun to drive” to potential buyers. Porsche has also differentiated itself by concentrating on the development of high-performance sports cars—while GM may offer a vehicle for every household budget, and Toyota may claim a high level of quality and reliability, neither have much appeal for the small number of drivers who look for speed, agility, and a sense that they could handle the raceway circuit at LeMans. That is what Porsche aims to deliver through its strategy of differentiation.

Differentiating a Commodity Product

Even among commodity products, business strategists have found and exploited opportunities to differentiate themselves. Although price and product features may be identical, it is still possible to differentiate on the basis of service. The cement business provides an example. Cement is cement, right? That’s the fact Mexico-based CEMEX, the world’s third-largest provider of cement, is faced with. Cement is a commodity product. Nevertheless, CEMEX has developed a strategy of fast and reliable delivery that qualitatively differentiates the company from its many rivals. As described by David Bovet and Joseph Martha in their book on supply-chain excellence, CEMEX has become a major industry power in many markets because it adopted a production and high-tech logistics strategy that achieves on-time delivery 98 percent of the time, versus the 34 percent record of most competitors. For construction companies operating on tight schedules, that reliability is highly valued, especially when a late delivery means that dozens of highly paid crew members will be standing around doing nothing. “This super reliability” write Bovet and Martha, “allows [CEMEX] to charge a premium in most markets, contributing to profit levels 50 percent higher than those of its key competitors.”1 In this case, super reliability has effectively differentiated a commodity product. Something similar may be achieved by offering superior customer support.

Effective Differentiation

Is your company following a strategy of differentiation? If it is, what sets it apart from the products and services of rivals? Whatever the answer, remember that differentiation only matters to the extent that customers value the difference. Maybe not all customers, but the ones you have targeted. If these customers truly value that which sets your product or service apart, they will either (1) select your offering over those of others, (2) be willing to pay a premium for what you offer, or (3) act on some combination of 1 and 2. Experience and market research are the best ways to determine if your difference will be valued by customers.

Customer Relationship

Everyone knows that you can buy a camera or wide-angle lens for less at Wal-Mart, Best Buy, or one of the other discount stores. Film and film-processing are cheaper at these stores as well. But many people still patronize small, independently owned photography shops when they purchase cameras, accessories, and films. Likewise, Fantastic Sams, a national franchise, provides great hairstyling services at low prices, yet many—if not most—women will pay more to go to the stylist who has been handling their hair for the past many years. Many women, in fact, can claim a longer-term relationship with their male hairstylists than with their husbands! In the words of one, “A husband is replaceable—a good hairdresser isn’t.”

What’s going on here? Why do so many customers pay more to patronize local camera shops, hairdressers, corner bookstores, neighborhood meat markets and bakeries, and many other vendors of goods and services when they could get a cheaper deal elsewhere? The reason is that they value the personal relationship experienced in doing business with these companies, their owners, and their employees. That relationship can take many forms: doing business with a familiar face; the fact that the vendor knows the customers and their needs; or the vendor’s willingness to explain the product, how to use it, and the pros and cons of different purchase choices. These are qualities you cannot find online, in a direct-mail catalog, or at most “big-box” stores. Those vendors provide a transaction, but not a relationship.

Relationship Strategy at Work: USAA

While big companies are at a disadvantage in building and executing a customer relationship strategy, it is not impossible. (See “Focus Strategy—What’s Different?” for another way of creating a a good customer experience.) Consider the case of USAA (United States Automobile Association). Not many readers will have ever heard of this Fortune 500 financial services company even though it has $71 billion under management. That’s because it caters exclusively to a very small slice of the total U.S. population: active duty officers and enlisted personnel, National Guard and Reserve officers and enlisted personnel, officer candidates, as well as dependents and former spouses of the above.

The people in USAA’s target market, however, know the company very well, and a large percentage of them are customers of its banking, insurance, and credit card services. Among active-duty officers, participation is 90 to 95 percent. And because it is a mutual company, customers are also part-owners.

After decades of serving this population, USAA understands its unique banking, insurance, and retirement needs. And it knows how to deal with the fact that military officers are transferred from post to post and around the world with great frequency. Its understanding of customers is expressed in many ways that people appreciate. For example, when customers are deployed overseas or to a war zone, their cars are usually put in storage for one or more years; in these cases USAA urges them to request elimination of the costly liability component of their auto insurance policies. No other auto insurer would think to do that. And unlike other life insurers, its policies have no war clause provision. USAA customers know that full policy death benefits will be paid if they die for any reason, including wartime service.

USAA’s close relationship with its military clientele and its understanding of their unique lifestyle can be traced back to its founding in 1922 by twenty-five army officers who found it difficult—owing to their profession and mobility—to obtain auto insurance. Even today, a substantial number of USAA executives and employees are former military people, and customer-serving employees are given extensive training on the unique financial needs of military personnel.2 Personal service is their highest priority.

Focus Strategy—What’s Different?

Many authors point to focus as one of the generic strategies. As described by Michael Porter in his landmark book, a focus strategy is one that is “built around serving a particular target very well, and each functional policy is developed with this in mind.”a In many respects the focus strategy and customer relationship strategy go hand-in-hand. It is next to impossible to develop serious relationships with anything but a highly focused, clearly targeted customer segment, as in the USAA example. On the other hand, a focus strategy can exist independent of relationships. Consider the case of Cracker Barrel Old Country Store, a nationwide chain of restaurant/gift shops that focuses on travelers who like traditional foods, particularly motorists who travel the U.S. interstate highway system. Cracker Barrel offers country-style meals and gift items in each of its locations. To encourage repeat visits, the company Web site includes a “trip planner” that identifies the locations of all Cracker Barrel outlets along any “tofrom” driving route. It is doubtful that many travelers perceive any relationship benefits from their visits to Cracker Barrel, but they do seem to appreciate the consistency of the food, ambience, and shopping opportunities it provides. Repeat customers know exactly what to expect from these facilities, which makes the choice of where to stop for a meal easy for people on long driving trips.

a Michael E. Porter, Competitive Strategy (New York: The Free Press, 1980), 38.

USAA focuses on a much narrower market segment than just about any other Fortune 500 company, but that focus and attention to customer relationships has paid off in terms of revenue growth, profitability, and customer satisfaction. In 2004, a poll of affluent investors put USAA at the top, with a satisfaction score 8 percent higher than TIAA-CREF, which also serves a highly focused market group, and 73 percent higher than Fidelity, which serves the general public. That same year, a survey conducted by Forrester Research put the company at the top among financial services companies for customer advocacy. Customer advocacy, according to that study, is customers’ perception that a company is doing what’s best for them and not just for the company’s profitability. “USAA scored highest in our ranking, in part,” according to a Forrester news release, “because of its focus on simplifying customers’ lives through efficient call center experiences. Many large banks, on the other hand, are at the bottom of our ranking because many of their customers feel nickeland-dimed.” 3

Making the Customer Relationship Strategy Work

Companies like USAA succeed to the extent that the relationships they build with people add real value—as perceived by customers. That value can take many forms:

- Simplifying customers’ lives or work. A USAA auto insurance holder does not have to obtain a new insurance policy every time he or she is transferred to another state.

- Ongoing benefits. Microsoft gains relationship points through its practice of notifying software users of critical updates, which can be downloaded by customers without charge.

- Personalized service. Many top-tier hotels have developed personalized approaches to handling repeat visitors by storing check-in information and customer preferences in their companywide data bases. This enables express check-in, gives customers the service they want, and adds a personal touch: “Welcome back to XYZ Hotels, Mr. Jones. We have a nonsmoking room for you. Do you still prefer having the Wall Street Journal delivered with your continental breakfast?”

- Customized solutions. Most companies continue to sell one-sizefits-all products and service; if you can develop the ability to economically customize your offering to the unique requirements of individual customers, you will build a stronger personal connection to them.

- Personal contact. Instead of channeling incoming customer calls to whichever service rep is available, give every established customer an account representative; this puts a personal voice on what would otherwise be an impersonal transaction.

- Continuous learning. Many companies have adopted CRM (customer relationship management) techniques to better understand and serve their most loyal and profitable customers. CRM identifies contact points between customer and company, and views each as an opportunity to learn more about customer needs.

A strategy based on customer relationships can produce powerful results and strong customer loyalty. The danger, of course, is that many people profess a strong affinity for the personal touch but turn to the low-cost provider when large sums are at stake. As one homeowner put it, “I usually patronize the small hardware store in my neighborhood. The owner knows me and I can count on him for advice when I have to repair a leaky faucet, install ceramic tile, or do some other job. But when it comes to big purchases—expensive power tools or something of that nature—I end up at Home Depot. I can’t afford not to.” The vendor’s challenge in these cases is to keep control of major purchases.

Network Effect Strategy

When the first telephones were sold in the late nineteenth century, they weren’t particularly useful. A person could only call one of the few other owners of the new gadget. But the telephone’s utility grew as more and more homes, stores, and offices joined the telephone network. This is called the network effect—a phenomenon in which the value of a product increases as more products are sold and the network of users increases.

As a strategy, the network effect is fairly new. Perhaps its most obvious practitioner and beneficiary is eBay, the online auction company. eBay began as a hobby business of its founder, Pierre Omidyar, who developed software and an online system that allowed individuals to list new and used items of all types for auction. His wasn’t the first online auction site, but it was the first to become widely popular, and that popularity sent the network effect into high gear. Buyers flocked to eBay over other sites because it had the most sellers, and sellers listed their items on eBay because it attracted the most buyers. This virtuous circle quickly established Omidyar’s site as the dominant online auction site, and it continues to support eBay’s remarkable growth.

There is no evidence that Omidyar and his colleagues set out with an implicit network effect strategy. It simply happened. However, early success encouraged them to use their rising tide of revenue to keep the ball rolling, which they did through heavy investments in site development, customer service, brand recognition, and a number of strategic acquisitions.

Success with a network strategy depends heavily on a company’s ability to get out in front and become the dominant provider. Doing so leaves very little space available for challengers, which is why some call this a winner-take-all strategy. eBay quickly dominated its industry. Microsoft did the same with its Windows operating system, though most experienced computer users agree that the userfriendly Macintosh operating system developed by Apple Computer is superior to Windows. But Apple kept its operating system proprietary, while Microsoft allowed its operating system to be installed on all PC manufacturers’ machines. Thus, since most PCs operated with Windows, most new software was developed for Windows machines. And because most software was Windows-based, more people bought PCs equipped with the Windows operating system. To date, no one has broken this virtuous circle.

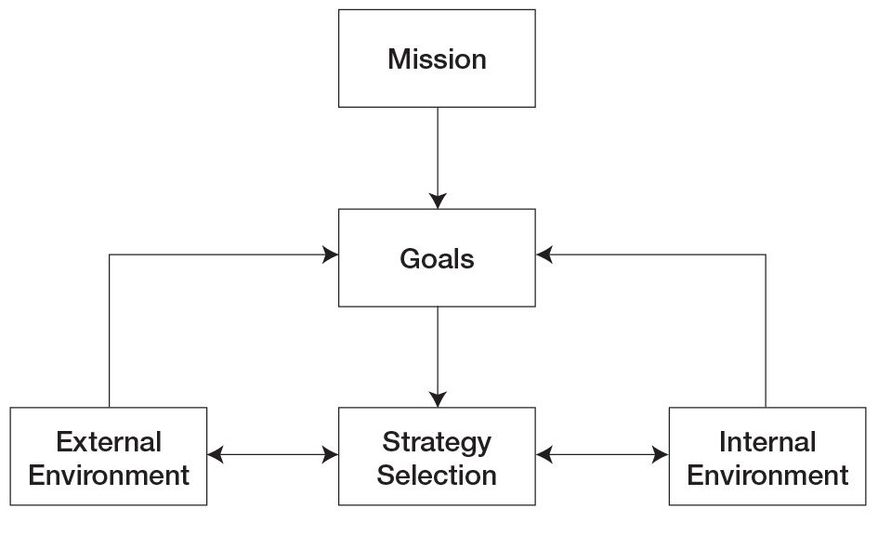

This chapter has presented four general strategies. Each has been a winning ticket for any number of companies. Chances are that one or another—or some variation—would be appropriate for your company. But which one? Look for the answer in your company’s mission, its goals, and what you have managed to learn through external and internal analysis, as described in figure 3-3. Think of the mission as setting the boundaries within which you may seek a new strategy. Your goals set the bar of achievement that the strategy must be capable of attaining. Then use SWOT analysis to identify threats and opportunities as well as the current capabilities of the organization. These three factors—in consultation with people who know and understand the many facets of your industry—will guide you to the right choice.

You should understand, however, that any strategic choice involves trade-offs. If you choose to focus on a narrow set of customers, as in the USAA example, you’ll have to give up the idea of serving the broad general market. As Michael Porter has warned, “Companies that try to be all things to all customers . . . risk confusion in the trenches as employees attempt to make day-to-day operating decisions without a clear framework.”4 Thus, if you want to be the low-cost retailer in your field, don’t try to set up a special boutique chain of stores to cater to high-end customers. You’ll confuse the market and yourself—and probably lose lots of money.

Which Strategy Is Best?

Above all, make sure that your choice of strategy is aligned with the primary customer market you plan to address. This may be the most critical factor in strategy creation. Keep your chosen customer market in your sights at all times, and make sure that your colleagues do the same. Alignment between strategy and customers is absolutely essential.

Summing Up

- As a strategy, low-cost leadership is most appropriate in industries in which competitors essentially offer a commodity-like product or service.

- Continuous improvement in operating efficiency, process reengineering, exploitation of the experience curve, supply-chain power, and product redesign are among the methods used to achieve low-cost leadership.

- A differentiation strategy sets the product or service apart from those of rivals in a qualitative way.

- Commodity products—those with standard features, quality, and price—can be differentiated from those of rivals by means of faster, more reliable delivery and/or superior customer support.

- Strong customer relationships can be used to retain customers who would otherwise gravitate toward lower-cost providers.

- To be effective, a customer relationship strategy must provide something that customers value—for example, something that simplifies their lives or work, ongoing benefits, personalized service, or customized solutions.

- The network effect is a phenomenon in which the value of a product increases as more products are sold. Companies that pursue this strategy (or benefit from it) succeed to the extent that they can get out in front and become the dominant provider of some enabling product or service, such as eBay’s online auction site or Microsoft’s Windows operating system.

- Whichever strategy type you consider, always look for alignment between the strategy and your target customer market.