2

SWOT Analysis II

Looking Inside for Strengths and Weaknesses

Key Topics Covered in This Chapter

- Identifying and assessing core competencies

- Understanding your financial capacity for undertaking a new strategy

- Evaluating management and organizational culture in terms of change-readiness

- A nine-step method for evaluating strengths and weaknesses

HAVING TESTED THE outer world for threats and opportunities, strategists must look inward and evaluate their strengths and weaknesses as an enterprise. As with the outer world, knowledge of the inner world imparts a practical sense about what company goals and strategies are most feasible and promising.

What are a company or unit’s strengths and weaknesses? The cost structure of its operations is one place to look for answers. Another is the company’s brands. Are they powerful and capable of extending the organization’s reach into the marketplace? How about its pipeline of R&D projects, and the acumen of its employees?

There is much to be considered in an internal analysis. This chapter addresses three of the most important areas in which a company’s strengths and weaknesses should be evaluated: core competencies and processes, financial condition, and management and culture. It then presents a method you can use for conducting your evaluations.

Core Competencies

A core competence is a potential foundation for any new or revised strategy. The term core competency refers to a company’s expertise or skills in key areas that directly produce superior performance. One of Sony’s core competencies, for example, is its ability to unite microelectronics and innovative design in a stream of useful consumer products. Corning has enormous competencies in the area of glass and ceramic materials and has used those competencies strategically over the years to produce successful product lines, from Pyrex ovenware to television tubes to fiber optics to the innards of catalytic converters. Bechtel counts large-scale project management among its core competencies; whether the job is building a new airport for the capital of Peru or a petrochemical complex in China’s Guangdong Province, Bechtel know how to tackle a big task and get it done.

What are your company’s core competencies? Don’t answer this by simply stating what your company does: “We make lighting fixtures.” Instead, determine what you are uniquely good at—better than others—and that customers value. In some cases, what you’re good at may be a core process—that is, a key activity that turns inputs into outputs. Core processes are the ones that make or break your business. 3M, for example, has a process for turning out dozens of new, customer-pleasing products every year. Over the years, it has learned far better than most how to generate promising ideas—many in the area of adhesives—and convert the best of these into real solutions to consumer and industrial problems. For USAA, the memberowned financial services company, handling customer transactions is a core process, and one that it does particularly well.

One warning: Being exceptionally good at something does not in itself confer a strategic advantage. You must be exceptionally good at something valued by customers. This might seem obvious, but some executives overlook it. You must also be better than others.

One way to assess the relative power of your core competencies and core processes is through benchmarking, an objective method for rating one’s own activities against similar activities performed by organizations recognized for best practice. In addition to providing a method for rating oneself, benchmarking aims to identify opportunities for process improvement. The benchmark target may very well be in another industry. For example, when Xerox discovered problems in its parts and components logistics operation, it sent a team of people to Freeport, Maine, to study how L.L. Bean, the popular and successful direct-mail clothing and equipment retailer, managed its picking and packing of individual customer orders. What the Xerox team learned was then used to improve its own handling of customer orders.

Remember, a competency is only meaningful in context. (See “Is Your Unique Competency a Sound Basis for an Effective Strategy?” for a look at evaluating core competencies.)

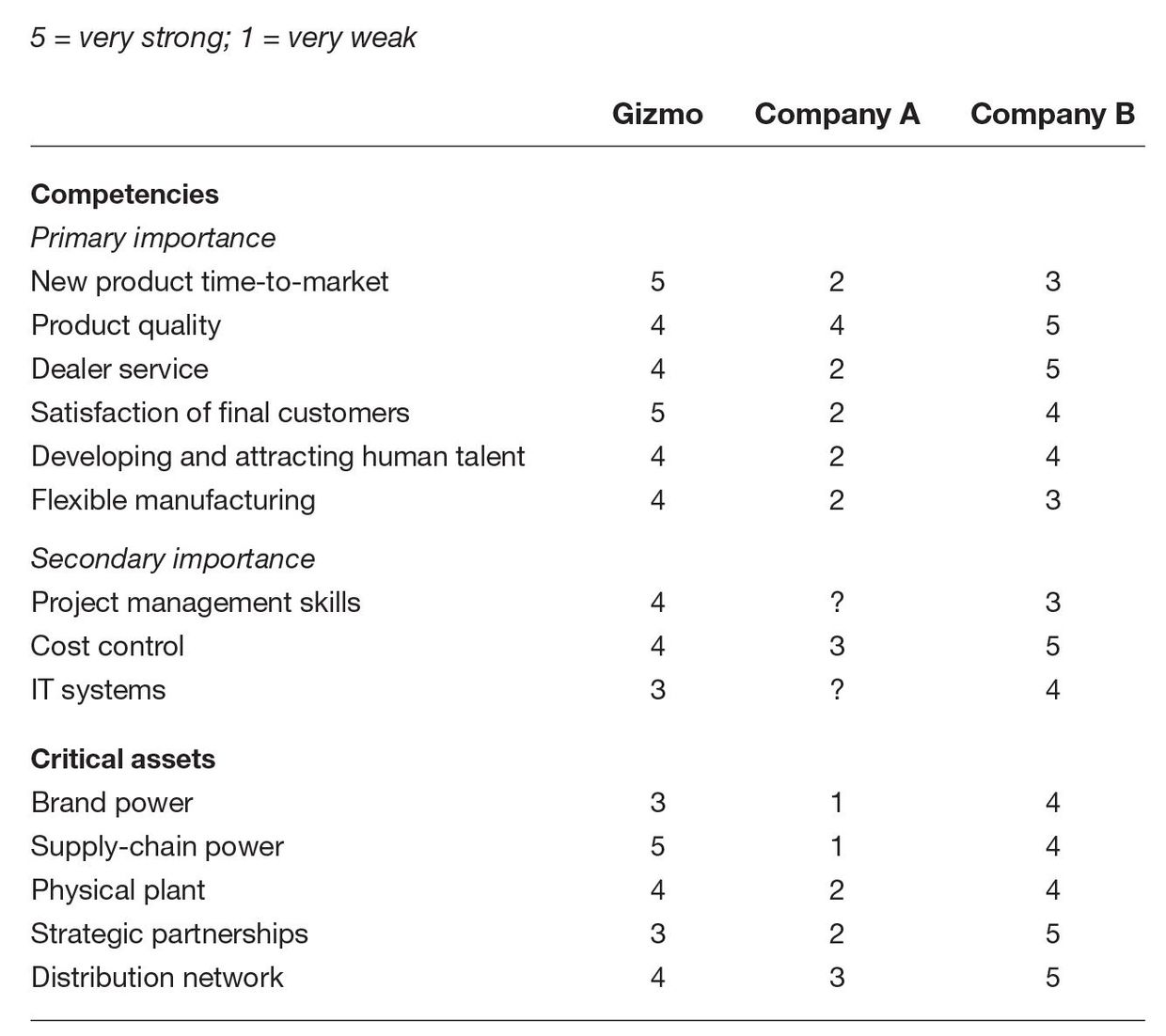

Here is an example of a method you can use to systematically assess the strength of your core competencies relative to those of rivals. The hypothetical company in this example is Gizmo Products, Inc., a designer and manufacturer of high-end cooking ware. In this exercise, it has compared its competencies in critical areas to those of Company X and Company Y—both serious competitors (see table 2-1). Notice that areas of primary and secondary competitive performance are identified.

Ratings like the ones shown in the table can help managers and executives identify strengths and weaknesses in the areas that matter most. These ratings can often be obtained by means of brainstorming among company personnel. But employee views may lack objectivity and suffer from incomplete knowledge. So, if you adopt this method, be sure to bring in the voices of salespeople, defectors from rival companies, and consultants who know the industry well. Make use of any survey data your market research has conducted on customers and distributors. Also look to quality and repair incidences compiled by objective third parties. What you want is an unvarnished assessment of where your company is strong and weak relative to key competitors.

This method of assessment differs from the traditional benchmarking exercise in that it examines many key aspects of company competence, not just one. And like benchmarking, it has a methodological weakness: It provides a snapshot of where different companies stand at a point in time, when the trajectory of competence is what matters for the future. For example, in table 2-1 Gizmo appears stronger than Company B in terms of flexible manufacturing, a key competency. Gizmo rates a 4 versus Company B’s 3 on this important measure. However, Gizmo may be losing relative strength in this area while Company B may be improving rapidly from year to year. Thus, next year, Gizmo may have lost its lead in flexible manufacturing. So add a sense of trajectory to your assessments, as in table 2-2. This table indicates that Gizmo is declining, Company A is on a plateau, and Company B is improving its competence in flexible manufacturing.

Is Your Unique Competency a Sound Basis for an Effective Strategy?

To be the basis for an effective strategy, a particular core competency or resource must be valued by customers. But it must also pass the following tests, according to David Collis and Cynthia Montgomery:

- Inimitability. It must be hard to copy. Don’t try to base a long-term strategy on something that your competitors can quickly copy.

- Durability. Durability refers to the continuing value of the competence or resource. Some brand names, like Disney’s or Coca Cola’s, have enduring value. Some technologies, however, have commercial value for only a few years; then they are swept aside by new and better technologies.

- Appropriability. This test determines who captures the value created by your competency or unique resource. In some industries, the lion’s share of profits goes to retailers, not to the companies whose ingenuity developed and produced the actual products.

- Sustainability. Can your special resource by trumped by a substitute?

- Competitive superiority. Is your special competence or resource truly superior to those of competitors? As Collis and Montgomery warn, “Perhaps the greatest mistake managers make when evaluating their companies’ resources is that they do not assess them relative to competitors’.” So always rate your strength against the best of your rivals.

SOURCE: David J. Collis and Cynthia A. Montgomery, “Competing on Resources,” Harvard Business Review (July–August, 1995), 118–128.

Comparing Core Competencies and Resources

Evaluating Competencies with Trajectory

Financial Condition

If a new strategy is the point of your internal analysis, you’d better assess the current financial strength of your organization. After all, a new strategy may be costly to implement, especially if it potentially involves the purchase of assets or the acquisition of some other operating company or unit. So ask the CFO to provide a full report that includes the following:

- Cash flows. To what extent are cash flows from current operations sufficient to support a new initiative? A fast-growing company usually gobbles up cash flow from operations and then has to go hunting for outside capital to finance growth. A mature, low-growth company, in contrast, can often finance a new initiative from operating cash flow from current operations.

- Access to outside capital. If cash flow is insufficient to finance a new strategy, the company will have to look to outside creditors and/or investors. So determine the company’s (1) borrowing capacity, (2) ability to float bonds at a reasonable rate of interest, and (3) in the event of a major initiative, its ability to attract equity capital through a sale of company stock.

- Other scheduled capital spending plans. Your company may have already approved other capital spending projects. If it has, those might absorb all available capital. Get a list of these scheduled projects and determine the extent to which they will compete for resources with any new strategy.

- Hurdle rate of new projects. The hurdle rate is the minimum rate of return expected from new projects that require substantial capital investments. It is usually calculated as the enterprise’s cost of capital plus some expectation of profit.

The financial performance of current operations is also something you should acquire from the CFO—in particular, the company’s return on invested capital and its return on assets. You should also know if these return figures are trending upward, trending downward, or stable. Why bother with these returns? Because they are measures of profitability, and any new strategy must be capable of improving on them. These returns represent baselines against which the contribution of any new strategy must be compared. For example, if the company’s current return on invested capital is 12 percent—and stable—any new strategy would have to improve that measure of profitability.

Management and Culture

Some companies can recognize when a shift in direction is necessary, and have both the management competence and organizational culture required for successful change. Others do not. It took many years, for example, for the management of General Motors (GM) to recognize the seriousness of the threat posed by Asian competitors. Once those executives were alert to the threat, their well-intended plans for change were hobbled by a vast organization, installed plants, and labor contracts that made change difficult and painfully slow. Employees and critics alike joked that GM stood for “glacial movement.”

Like GM, every established enterprise faces problems of flexibility and adaptability to a greater or lesser extent. Years of practice naturally mold both managerial thinking and organizational forms to the requirement of the existing strategy. That is a virtue as long as the strategy makes sense, but a potential handicap when it doesn’t. So, as you look for internal strengths and weaknesses, ask this question: Is the company “change-ready”? A change-ready company is adaptive and prepared by structure and temperament to discard what is not working and move to strategies capable of better results. A change-ready company has these characteristics:

- Managers are respected and effective.

- People feel personally motivated to change.

- The organization is nonhierarchical.

- People are accustomed to collaborative work.

- There is a culture of accountability for results.

- Performance is rewarded.

Companies with these characteristics are in a good position to implement a new strategy. Those that lack them face a stiffer challenge.

A Method for Evaluating Internal Strengths and Weaknesses

While some company strengths and weaknesses can be quantified (e.g., return on assets), many others cannot. Some people may say, “Our company rewards performance,” while other employees of the same company may say just the opposite. To cut through these different perceptions, you need a method that involves many perceptive people representing different functions within the organization. Their collective judgment is bound to be more accurate than that of one or two bright individuals who see things from their narrow viewpoints. As James Surowiecki noted in his perceptive book The Wisdom of Crowds, “If you put together a big enough and diverse enough group of people and ask them to ‘make decisions affecting matters of general interest,’ that group’s decisions will, over time, be ‘intellectually superior to the isolated individual,’ no matter how smart or well-informed he is.”1 You also need a method for organizing this collective intelligence, which we offer you here in nine practical steps.2

- Step 1: Select an individual to facilitate the analysis. This person should be someone whom people trust and respect. He or she should also be viewed as objective and not aligned with any particular camp within the company.

- Step 2: Create a SWOT team of knowledgeable individuals from different functional areas of the company. Like the facilitator, team members should be trusted and respected by their peers and have reputations for objectivity and “truth telling.”

- Step 3: Brainstorm the company or unit’s strengths. Go around the room and solicit ideas from everyone. Consider the core competencies, financial condition, and management and organizational culture as described above. Also give some attention to leadership and decision-making abilities, innovation, speed, productivity, quality, service, efficiency, and applied technology processes.

- Step 4: Record all suggestions on a flip chart. Avoid duplicate entries. Make it clear that some issues may appear on more than one list. For example, a company or unit may enjoy some strengths in customer service, but have certain weaknesses in that area as well. At this point, the goal is to capture as many ideas on the flip charts as possible. Evaluating these strengths will take place later.

- Step 5: Consolidate ideas. Post all flip chart pages on a wall. While every effort may have been taken to avoid duplicate entries, there will be some overlap. Consolidate duplicate points by asking the group which items can be combined under the same heading. Resist the temptation to overconsolidate—lumping lots of ideas under one subject. Often, this results in a lack of focus.

- Step 6: Clarify ideas. Go down the consolidated list item by item and clarify any items that participants have questions about. It’s helpful to reiterate the meaning of each item before discussing it. Stick to defining strengths. Restrain any urge to talk about solutions at this point in the process.

- Step 7: Identify the top three strengths. Sometimes the top three strengths are obvious. In that case, simply test for consensus. Otherwise, give participants a few minutes to pick their top issues and vote on them. Allow each team member to cast three to five votes (three if the list of issues is ten items or fewer, five if it is long). Identify the top three items. If there are ties or the first vote is inconclusive, discuss the highly rated items from the first vote and vote again.

- Step 8: Summarize company strengths. Once the top three strengths are decided, summarize them on a single flip chart page.

- Step 9: Repeat steps 2 through 6 for company or unit weaknesses. Like strengths, areas of weakness for a company or unit include core competencies, finances, management and culture, leadership abilities, decision-making abilities, speed, innovation, productivity, quality, service, efficiency, and technology.

(Note: You can use this same method in tapping collective insights on threats and opportunities, as described in the preceding chapter on external analysis. You might want to expand the SWOT team, however, to include people from outside the company: a supplier who knows the industry intimately and with whom you work regularly, a consultant with broad industry experience, and so forth.)

Once you have completed the nine steps, your SWOT team should compile its findings in a formal report for the benefit of top management, strategic planners, and other interested parties. And if you’ve done the same for external analysis, your company will be ready to move on to the business of creating a strategy.

Summing Up

- A core competency is a potential foundation for any new or revised strategy.

- A competency is meaningful only when compared with that of rivals.

- Assess the current financial strength of your organization before thinking about strategy. A new strategy may be costly to implement, especially if it involves the purchase of assets or the acquisition of some other business.

- Management competence and organizational culture are required for successful strategic change.

- Determine if the business is change-ready by looking for these characteristics: Managers are respected and effective; people feel personally motivated to change; the organization is non-hierarchical; people are accustomed to collaborative work; there is a culture of accountability for results; and performance is rewarded.

- Don’t rely on one or two people to do internal analysis. Instead, bring together a small group of objective people representing different activities in the organization. Have them use the nine-step process outlined above.