Put Your Culture to Work

What’s your company’s biggest asset? We often asked this question in interviews we conducted with leaders of companies that had closed the strategy-to-execution gap. These leaders nearly always named their culture.

At CEMEX, human resources chief Luis Hernández said the culture “produces the behaviors that reinforce the capabilities that will make us successful.”1 Haier’s CEO Zhang Ruimin said that “the main factor enabling [the difference between Haier and other companies] is our culture.”2 Peter Agnefjäll, CEO of the INGKA Group at IKEA, said, “Our culture is very difficult to copy. You could copy our Billy bookcase or the retailing format or our warehouses, but how do you copy our culture?” We could quote similar remarks from leaders at Danaher, Lego, Natura, Qualcomm, and Starbucks. These cultures may not always be friendly; they can be tough on people. But they are always seen as a source of strategic strength.

To be sure, executives at most companies talk frequently about their culture. But all too often they describe it as something to overcome: an impediment to performance. They launch “culture change” initiatives to eliminate negative cultural attributes and build new ones. These efforts prove futile; a culture does not change easily or rapidly.

An organization’s culture is a multidimensional, complex, and influential thing. It is the reservoir of behaviors, thoughts, feelings, values, and mind-sets that people in an enterprise share. Culture influences the most common practices of an organization, many of which are more informal than formal, especially those practices which people take on themselves and which may not be consciously recognized or talked about explicitly. Like tacit knowledge, a culture can’t be managed by controlling it; but its impact is concrete. “Cultural forces are powerful,” writes Edgar Schein, the MIT professor who first articulated the concept of corporate culture, “because they operate outside of our awareness.”3

In most companies, the culture manifests itself in the way people look at things and talk to each other; in the way they compliment and criticize one another; in the posters on the wall and the knickknacks on the desks. Most of all, it is evident in the stories people tell each other, about what matters at this company or why some people fit in while others don’t. Thus, closing the gap between strategy and business often involves telling new stories that are deliberately chosen to reinforce coherence: stories about the capabilities that make this company special, the reasons why we do the things we do, events that have challenged the enterprise, the things people did to meet those challenges, and the evolution of the company’s capabilities and attitudes. (Indeed, these are the kinds of stories that came up repeatedly in the research for this book.) It isn’t necessary to become a good storyteller to lead a company in this direction; but it is necessary to become aware of the prevailing stories, and how well they fit the identity of the enterprise. If there are serious contradictions, then it may be necessary, as we’ll see later in this chapter, to find the stories that fit better, and bring them to the surface.

Your culture is a valuable resource. Learning to work with your culture can make the development of differentiated capabilities much easier. In a relatively coherent company, when strategy and execution are closely aligned, the culture provides the support that individuals within the enterprise need to find their own personal connection with the overall strategy. It helps break down the barriers that separate strategy from execution, such as the boundaries between functions. A culture that is in tune with your most distinctive capabilities can also draw people to accomplish amazing things.

Most business leaders understand the power of a company’s culture. But it’s not always clear how to harness that power. To do so, you must understand the way that culture evolves as you close the gap between strategy and execution, and how it can help you move further down that path. This chapter has three main points. First, we explore the way a company’s identity shapes its culture. Then we look at three facets of culture that all of the companies we studied seem to have in common: emotional commitment, mutual accountability, and collective mastery. Finally, we describe a focused “critical-few” method developed by Jon Katzenbach that you can apply in your company to accelerate the cultural evolution already going on there. Coherent companies use their cultures this way to truly differentiate themselves by bringing their strategic identity to life.

Fostering a Distinctive Culture

Peter Agnefjäll hits on an important point when he says IKEA’s culture is difficult to copy. Like almost everything else about them, the cultures of coherent companies are unique and hard to replicate. No other retail chain can adopt the practices of Starbucks or Zara and expect the same result; the people in these companies behave the way they behave because a culture has grown up, over time, which reinforces this behavior.

Many very capable people are drawn to work for companies with distinctive capabilities. Although they might not think of it as an emotional connection to the company’s culture, that’s what attracts them. They want to be part of something distinctive. Thus, at companies that close the gap between strategy and execution, you don’t typically find people trying to leave their culture behind. They celebrate the bespoke attributes that make them special, and they keep bringing those elements to the forefront. In a coherent company, the elements of the culture, often dismissed as merely personal, reinforce what the company is trying to be.

Consider, for example, how Natura’s culture expresses and reinforces its identity. Every artifact, from the product designs to the architecture of the buildings, is a testament to the company’s shared purpose and values. Even the annual reports open with this statement: “Life is a chain of relationships. Nothing in the universe stands alone.”4 The culture goes a long way toward reinforcing the relationship with sales consultants at the heart of Natura’s value proposition. You can also see its impact in the company’s relationships with rain forest suppliers, and its intent focus on keeping promises. The culture is also reflected in the way people talk about the company. “We are driven by language,” says brand director Ana Alves. “We tell stories. This comes partly from the Brazilian culture; you understand things in part by feeling them.” And it is manifest in its architecture. Visitors to Natura’s headquarters in Cajamar, a suburb of São Paulo, encounter a six-story glass-and-steel building, with the upper three stories built on stilts to promote airflow and a bowstring bridge that encourages people to linger and look at the forest around them. The company has been regularly planting seedlings to recover the native biome on the site since 2009, when the building opened.5

Some forty-seven hundred miles to the north is Danaher—an equally coherent company with a completely different culture, one that centers around operational effectiveness, ruthless execution, and no-nonsense candor. It’s a necessary culture for an enterprise assembled from other companies who must all operate as high achievers, helping one another continually do better. There is no room for slack or indecisiveness. When you run a business at Danaher, it’s understood that your performance might drop sometimes, but you’d better be prepared to explain what happened and what you are going to do about it, with lots of data and no embellishment. “If you’re touting pabulum, that’s an unsafe place to be,” says Steven Simms, who spent eleven years at Danaher and is now CEO of another manufacturing company. Danaher’s global headquarters occupy an unpretentious floor in a building in downtown Washington, D.C. “We are nonpolitical and nonbureaucratic,” says the company’s culture statement. Executive vice president Jim Lico adds, “We have the soul of a small company. We still remember the day when we all pitched in to ship product on Fridays if the warehouse was full, or we took a tech support call even if we were top executives. Though those days are long gone, we remember and long to keep that culture.”

We could paint a similarly compelling portrait of every company that we credit with closing the strategy-to-execution gap. Apple, Amazon, and Starbucks are famous for their idiosyncratic cultures, and you’d find a similarly distinctive sensibility in Frito-Lay, Inditex, Lego, and Qualcomm. They don’t take their culture for granted. Moreover, the cultures of these companies are directly linked to their capabilities systems. Natura doesn’t just have a commitment to environmental and social sustainability; its people know how to achieve it because it is one of their distinctive capabilities. The culture reflects not just what people believe, but what they do exceptionally well. Behaviors lead to stories; stories engender new behavior; and everything ties in with the value proposition and capabilities system. That’s why these cultures are so different from each other.

You may think of your company as having a standard, nondescript business culture, just like everyone else’s, but it too is unique. It has come to life over time through the accumulation of many factors: the background of your company’s founders and key leaders, its geographic roots (companies founded in Silicon Valley tend to be different from companies founded in the Netherlands or in Singapore), its prominent functions, its history of mergers and acquisitions, and its structural constraints (highly regulated industries lead to cultures different from those in more freewheeling industries). Your company’s culture is unlike any other, and that distinction is a strength.

Now that you are moving to close the gap between strategy and execution, it is time to celebrate and use that distinction. You can foster commitment with it; you can bring your value proposition to life. Think of your culture as the “intrinsically cool” part of your identity—the part that engages people. When you talk about your company’s culture, articulate the ways in which it reflects your capabilities system and the value your company creates.

If you’ve already begun to work on the first two of the five acts of unconventional leadership as outlined in chapter 1—namely, committing to an identity and translating the strategic into the everyday—then this articulation has probably already begun to happen. Your effort to build capabilities and bring them to scale have already highlighted the amazing things your people can do. People naturally identify with their capabilities, especially if shared by an elite organization full of highly skilled colleagues. Companies that define themselves by their capabilities, instead of by their financial results or an abstract mission statement, thus enjoy a huge cultural advantage.

Finally, while the distinctiveness of your culture is a strength, coherence does seem to bring with it three common cultural elements: emotional commitment, mutual accountability, and collective mastery. These will tend to emerge as you practice the five unconventional acts enumerated in chapter 1. Most companies are familiar with these elements—but only in places. As you close the gap between strategy and execution, you will increasingly be able to rely on them. Let’s look at these three elements, the natural outcomes of those unconventional acts, in more detail.

Emotional Commitment

Suppose, then, that you are on your way—that you are following the first two acts, and your company has a clearer identity and a stronger capabilities system. One of the first changes you will notice is a rise in the level of emotional commitment. When people understand the identity of the enterprise, and when they feel aligned with that identity, they are ready to give more of themselves to the enterprise, because they see its success as their own.

Emotional commitment is impossible to measure precisely. It may not even show up reliably in employee engagement surveys. But people who are attuned to it can generally tell when it’s present. “You can walk into [any type of retail store],” CEO Howard Schultz is quoted as saying, “and you can feel whether the proprietor or the merchant or the person behind the counter has a good feeling about his product. If you walk into a department store today, you are probably talking to a guy who is untrained; he was selling vacuum cleaners yesterday, and now he is in the apparel section. It just does not work.”6

At some companies, the emotional commitment begins with devotion to some aspect of the company’s identity, such as the product. Michael Gill, author of How Starbucks Saved My Life, first connected with the company through a love of coffee. Many are drawn to Natura, Lego, and Apple because of appreciation for the elegance of their products. Other companies, such as Danaher and Qualcomm, generate emotional commitment through appreciation for the skill of their employees. And some companies, such as Inditex, inspire commitment when employees understand how their role fits with the company’s way of working. Whatever the initial connection may be, when a company is coherent, that commitment expands to include a strong affinity for the company, its people, and its community.

The experience of Natura shows how emotional energy changes a company’s perspective. As we noted earlier in this book, the company’s slogan, bem estar bem, translates to “well-being, being well.” When asked what’s important to the culture, people talk about two things: the products and the company’s relationships with people. The products themselves are designed and packaged to evoke long-term vitality, cherished relationships, and other aspects of personal commitment. A fragrance is scented to remind people of the Amazon rain forest (from which its ingredients are sourced); a skin cream is designed for grandchildren to give their grandparents; a moisturizer called Tododia (“Everyday”) deliberately evokes the pragmatic pride of a professional on her way to work. Featured among several seductive fragrances for men and women is one called Brasil Humor, which is intended to encourage “a more humorous take on life.”

Conspicuous by their absence are performance-oriented claims. Natura’s anti-aging creams and moisturizers never promise to reduce wrinkles by a particular percentage. Such claims don’t fit with the products’ value proposition, which itself is grounded in emotional commitment—the commitment people make to their relatives and close friends. There are also practical reasons for avoiding these claims. “Some of our business units have asked for products where we can claim better performance than a competitor,” says R&D director Alessandro Mendes. “But if we tried to play that game, we could only afford to launch three or four new products per year.” Instead, Natura launches more than a hundred.7

Natura’s emphasis on the rich, multi-faceted, relationship-driven nature of daily life reinforces its emotional connection to the people who sell its merchandise. Within Brazil, the company maintains a network of 1.5 million “consultants,” as they’re called: individual representatives who are commissioned and trained by Natura. They show the products regularly to their friends, neighbors, and acquaintances—mostly door to door, although some operate small shops out of their homes. They take orders, distribute the products, and collect the payments. The company must therefore give them a reason to get in touch with their customers every twenty-one days: a hot-off-the-press product catalog, containing a few new products and seasonal specials (e.g., for Christmas or Mother’s Day) along with the company’s mainstays. Unlike most direct-sales companies, which have multilevel hierarchies of sales representatives and concentrate wealth at the top of the pyramid, Natura is directly connected to most of its consultants. They know that it is committed to their success, and therefore they return that sentiment.

The company proves its emotional commitment through its actions. For example, it makes heroic efforts to avoid shipping problems. Rather than outsource distribution, the company has invested millions in a state-of-the-art supply chain that delivers orders within two to four days, even to extremely remote parts of Brazil. Natura maintains very high flexibility in its supply chain because a well-liked new fragrance or cosmetic can suddenly take off, selling at one hundred times the average sales volume of other products. The company also maintains high reliability. In 2011, when the percentage of lost or damaged deliveries rose from near zero to about 1 percent, the company paid no bonuses. The following year, the failure rate fell back to zero. People at headquarters spoke of this measure as not just pressure for performance—but as a sign of the commitment they had made to its consultants.

In the early 2000s, Natura deepened its commitment—to employees, consultants, and customers—by broadening its capabilities system. It embraced a management principle known as the triple bottom line, that is, accountability for financial, environmental, and social success.8 This required types of proficiency the company had not had before: a new capability in sustainability-related management. The development of this capability began in 2000 when Natura launched a line of products called Ekos, using plants collected or harvested from the biodiverse Brazilian Amazon region. Denise Alves, the company’s sustainability director, recalls, “We decided that Ekos would only use ingredients from the Amazon region that would be extracted from fruits cultivated or collected in an organic way, in a quantity that would not hamper that region’s ecosystem.”

The sheer complexity inherent in this capability has become a barrier to entry for competitors and a differentiator for Natura. When its buyers collect ingredients from rain forest villages, they demand that the plants be grown and harvested sustainably. Natura compensates villages with long-term investments and has created a unique financing system to foster this approach. The company also works diligently to reduce air and water pollution at every step of the value chain, publishes data on its carbon and recycling footprints, designs sustainable packaging, and creates job opportunities for disabled people in its warehouses and factories.

One important moment came in the mid-2000s, when Natura ran out of an ingredient called pitanga, which is needed for one of the company’s most popular products. Other companies might have looked for less sustainable sources. Natura announced that it was stopping production until it could be sure that its procurement didn’t compromise company values.

With this move, Natura found itself embracing sustainability wholeheartedly. Since then, it has used triple-bottom-line reporting so consistently that if Natura doesn’t meet goals in all three areas everywhere in the company, Natura doesn’t pay bonuses. The company also energetically seeks to make its practices transparent to outsiders. Alves explains, “We pioneered an environmental table on our packaging that describes the product content and how much of the packaging is recycled, even when the numbers aren’t flattering to us.” Natura’s social programs have also expanded well beyond the typical level you might find in other companies. Executive vice president João Paulo Ferreira (who oversees sales, sustainability, and customer relationships) describes Natura’s approach:

If I go to the board and I say, “I need a new distribution center,” they say, “Okay, maybe.” But if I go as I did [in 2012], and say, “We should have a new factory, but I think we should make it an eco park with symbiotic industrial flows in the middle of the rain forest to increase our impact in society, and by the way I don’t have a clue how to do it,” the board will definitely accept, as they did.… If I say, “[We should design our next distribution center] to make sure that we can have a workforce of up to 30 percent mentally or physically disabled people, including autism and Down syndrome,” they say, “Okay, we want this. Go.” That’s the sort of thing we do.

Some of the other companies we looked at, such as IKEA and Starbucks have developed similarly deep commitments to environmental or social responsibility. The critical factor, all too often overlooked, is the link between that emotional commitment and the capabilities that support it. When a company voices this commitment and then cuts corners or hides data—as some do, with visible and extremely damaging results—the problem generally seems to be insufficient attention to the required capabilities. They just can’t figure out how to deliver. By contrast, its capabilities make Natura trustworthy. Customers who care about the rain forest or developmentally disabled people know the company keeps its promises. That emotional commitment has become part of Natura’s culture.

With headquarters in São Paulo, Natura is the leading cosmetics company in Brazil, with revenue of US$2.6 billion in 2014.

Value Proposition: Natura is a relationship-focused experience provider and reputation player, selling products that promote well-being, relationships, and connection to nature.

Capabilities System

•Direct-sales distribution: Natura maintains a uniquely powerful model of sales through qualified representatives (“consultants”).

•Rapid innovation: The company develops and markets a steady stream of new products that create an emotional connection with customers, consultants, and employees.

•Operational prowess: Managing the complexities in a company that manufactures and delivers more than one hundred new products each year, ensuring that consultants can reach out to customers every few weeks and enhance relationships.

•Creative sourcing: Natura builds and maintains a supplier network that gives the company unique access to rain-forest products and helps build Natura’s reputation as a sustainable company whose employees and customers believe in the value of relationships.

•Sustainability-related management: Natura makes environmental responsibility an integral part of operations and expresses those ideals in everything it does.

Portfolio of Products and Services: Natura develops, produces, and sells personal-care products, mainly in Latin America.

Mutual Accountability

When everyone in an enterprise is working together toward the same goal, they tend to strongly identify with each other. People think, “We’re all jointly responsible for fulfilling the goals we’ve set, or we will let each other down.” A differentiated capabilities system depends on this quality. People have to recognize one another’s contributions and how they can rely on these contributions, or they will be vulnerable themselves.

In their book The Wisdom of Teams, Jon Katzenbach and Douglas R. Smith report that mutual accountability is the clearest indicator of what they call a “real team”—a team whose people share goals and work interdependently, as opposed to merely being assigned to the same projects.9 This type of team-based collaboration is particularly important for distinctive capabilities, which are inherently cross-functional. When the culture reinforces the attitude that people are responsible for the success of the enterprise, not just for their functions, it is much easier to bring a distinctive capability to life.

Where there is mutual accountability, there is trust. Even in relatively harsh cultures, like Apple, there is a clear sense that people can be relied on to pull their weight. Adam Lashinsky quotes an unnamed Apple executive who explains the “culture of excellence,” as the executive calls it: “There’s a sense that you have to play your very best game. You don’t want to be the weak link. There is an intense desire to not let the company down. Everybody has worked so hard and is so dedicated.”10

In companies with mutual accountability, management doesn’t need to rely on command and control to get things done. “I was to learn,” Michael Gill writes of his experience as a barista, “that nobody at Starbucks ever ordered anyone to do anything. It was always: ‘Would you do me a favor?’ or something similar.” There is generally a culture of open experimentation in firms with mutual accountability, because people know that the full team will support anything that credibly leads to better long-term results. Everyone is invested in each other’s success, interested in making sure it goes right. That in itself enables everyone to be more adventurous.

The IKEA culture fosters this kind of accountability. Montserrat Maresch, global marketing and communications director at the INGKA Group, says, “We’re not an organization of superstars and divas. We’re much more tolerant with C performers than with C behaviors. If I’m not good enough but I have the right attitudes and the right values, I will be helped by the organization. In the same spirit, we don’t celebrate a high-performing store. We celebrate when that high-performing store helps a weaker store.”

The extent of mutual accountability can provide a clear test of your company’s coherence. Many companies have diverse business units and functions, each with its own budget or profit-and-loss statement, and the units or functions have never worked closely together before. As companies build distinctive capabilities and bring them to scale, they set up teams and conversations in which people have to engage more effectively with specialists from other parts of the enterprise. The conversations are illuminating: “I never realized what you did or why it mattered to me.”

Moreover, the mutual accountability of your enterprise can help overcome the short-term orientation and unproductive internal competitiveness that pervades many organizations and prevents them from doing amazing things. Once people feel responsible for each other’s success, they are more likely to take the time to understand each other’s perspectives. IKEA has used its high level of mutual accountability in precisely this way. Søren Hansen, the CEO of Inter IKEA Group (which includes Inter IKEA Systems B.V. along with independent property and finance operations), describes how mutual accountability works for his enterprise:11

One might think it would be easy for people to say, “No; this is not my responsibility,” and go off and paddle in their own pool, handling only their own tasks. But that’s not the way it is here. Everybody feels more responsible than they actually are on paper. As soon as there is an issue somewhere, people jump in, help, support. This creates checks and balances throughout the system. Indeed, there is no clear demarcation between functions, and you therefore feel responsible for the company and the end result.12

People who have worked in a culture of mutual accountability tend to remember it all their lives. They are in an environment where everyone is dedicated to everyone else’s success. At its best, the purpose of the company becomes the fulfillment of its members’ potential. This is not just because the company expects a return on its investment, but because it knows that the accountability of key employees is critical to distinctive capabilities.

Collective Mastery

Think back to the great teams you have known: where you and your colleagues seemed to sense what each other was thinking, where you all understood how your work fit into a common purpose, and where you recognized how to accomplish great things together, without needing to follow a script. Now imagine an entire global organization operating more or less this way. That is what a culture of collective mastery feels like. In the companies that we studied, collective mastery is prevalent. It is a high level of shared proficiency, visible across the enterprise, where people at the top of their individual games continually practice collaborating across functional boundaries to raise the overall quality of what they do together. They grow accustomed to thinking together: solving problems, minimizing formal rules that block progress, and experiencing the intrinsic joy of working with other high-caliber people.

A culture of collective mastery can lead a company to great achievement. The companies we studied, to the extent they have that culture, get there through the direct involvement of the senior executives of the company. They’re not just involved in the blueprinting of capabilities systems, but also in their implementation, including (as we’ll see in chapter 5), the details of resource allocation.

Most of all, they’re involved in the capabilities system of the enterprise: paying constant attention to its successes and failures, and routinely moving people to the positions where they can make the greatest contribution. Top leaders take a fresh look at every significant practice and ask, How well is it working? How can we improve it? What have we learned from it? In turn, they glean direct insight about the day-to-day business of delivering the enterprise’s strategy. Participating in this sort of capabilities-building work requires a great deal of effort, and few companies have the discipline to make it stick. Yet all the coherent companies do.

Consider, for example, Danaher’s approach to executive teaching and learning. The company’s Danaher Business System was directly influenced by the tenets of lean management and the quality movement, to the extent of learning directly from some of the Toyota leaders who developed that approach. But Danaher’s leaders were closely involved, from their first use of this system in the mid-1980s, in adapting and adjusting it to make it their own. They also devoted themselves wholeheartedly to the tools and methods.

“[Most managers] have a mind-set that if you apply a tool, you’ve done it and you’re done,” recalled George Koenigsaecker, who implemented the first version of the Danaher Business System in the 1980s. He said a single application of process improvement might yield 40 percent productivity gain. “But to get the 400 percent gain you have to pass it at least 10 different times. You must restudy the process over and over.”13 Over time, as you continue to apply the techniques of capability improvement—the point interventions and innovations that we described in chapter 3—this way of life becomes embedded in your culture. “Whether you’re in a strategic plan review, an operating review, a growth initiative, or walking the plant floor,” says retired executive vice president Steven Simms, “all the questions and challenging come back to some aspect of ‘How do we get better?’ It leads to great, rich discussions everywhere.”

The result is a company where not just practices, but attitudes and habits, are geared toward fostering collective mastery. Danaher’s culture evolved this way in part because, as a serial acquirer, the company has had to continually onboard new people and increase the reach of its capabilities system. “We have been learning how to extend the Danaher Business System to larger and larger scale for more than a decade,” says Danaher executive vice president Jim Lico. “In 2003, I was running the DBS office and [founder and board chair] Mitchell Rales asked me how I was going to teach DBS to twenty-four thousand people in the next three or four years. I said, ‘We only have twenty-four thousand people in the whole company.’ Mitch said, ‘Yeah, but we’re going to double in size in the next three or four years and that’s our task.’”14

The emphasis on collective mastery is evident in the way Danaher recruits, onboards, and develops people. It can take months to get a new executive onboarded, and the process frequently involves immersion in several businesses temporarily—with the explicit idea that both Danaher and the newcomer will learn from each other. Danaher also conducts a cascading series of meetings and initiatives, with top management involved, where the DBS methods are practiced. For example, the top twenty Danaher executives get together regularly to talk about tools and techniques related to key capabilities. “We quickly pick up everything we can from each other,” senior vice president Henk van Duijnhoven explains. “Not every operating company has to implement every tool; they choose the tools that will enable them to achieve their strategic goals, fix quality issues, or improve delivery or other operating company objectives.”

Regular meetings are not just devoted to decisions, but also consideration of how well the capabilities are working. “In each business,” CEO Tom Joyce says, “we have a disciplined cadence of monthly operating reviews: eight-hour face-to-face meetings with a standing agenda. It’s very data-driven. We focus on things that are not going well and what we’re going to do to improve them.”

The Danaher Leadership Conference is another organizational construct that reinforces scale and improvement at the company. It consists of a series of forty or fifty presentations highlighting best practices over three days for the top 100 to 150 leaders at the operating companies. “One [session] could be a story about how the water quality platform has captured customer insights for accelerated product development,” Simms says. “Another could be, ‘We finally learned to do policy deployment right after fifteen years.’ Each one explains the problem, the root cause of the issue, the countermeasures taken to solve it, what they’d do differently in retrospect, and what they’d advise you to do—with an email address and phone number. [The implied message is] ‘Call me, and we’ll talk about some ideas and people to help get you started.’ … Senior managers were actually rated every year on our proficiency with [the Danaher Business System] tools.”

Other companies we looked at have similarly involved top leaders as teachers and learners. During its most energetic efforts to develop new capabilities, JCI-ASG conducted meetings known as stake-in-the-ground sessions. Every few months, executives convened to report on cost-cutting measures they had identified, along with other measures designed to improve and focus on capabilities. The committee decided which ones to implement.

Starbucks takes this idea one step further. By establishing that every employee is a partner (reinforced with stock options), it also enlists every employee in developing collective mastery. The education of a Starbucks employee is an intensive, ingrained affair, with a great deal of one-on-one apprenticeship. It takes time and attention to learn the ins and outs of the espresso machines, the varieties of coffee, how to treat customers (including lengthy scripts that role-play different types of encounters at the register), and the ethics of community engagement. All of this is necessary, founder Howard Schultz suggests, because of the inherent complexity of the Starbucks system. The company must therefore give employees a deep and shared understanding of the underpinnings of the enterprise.

It is on-the-job practices like these, which may or may not involve formal training, that generate collective mastery. When enough people at a large enterprise participate in distinctive capabilities, paying close attention to what matters most about the work itself, they gain a collaborative proficiency that is greater than their individual skill. As we noted in chapter 3, they codify their tacit knowledge, processes, and practices into recipes that get rolled out to the entire enterprise. But, like master chefs, as people gain proficiency, they use the recipes less rigidly, more as launching points. They develop the confidence and sheer skill that comes from long experience and practiced creativity. Since they are working with other master chefs, they also gain a common frame of reference; they can act together with a range and scale that no individual artisan can match. “At Apple,” writes Lashinsky, “thirteen out of fifteen topics get cut off after a sentence of discussion. That’s all that’s needed.”15

Not surprisingly, one of the most tangible benefits of collective mastery is the ability to attract higher-caliber people. An organization that defines itself by what it does better than any other organization resonates with individuals who can contribute something significant. The ability to be an engineer or physicist at Qualcomm, a product designer at Apple, a platform leader at Haier, a customer-relationship manager at CEMEX, or a barista at Starbucks is more compelling than doing similar things elsewhere. On the companies’ side, the cultural clarity created by collective mastery makes it easy for them to see who fits and who doesn’t: Is a prospective Natura employee energized by relationship building? Does a prospective IKEA employee value frugality? If not, whatever the prospect’s other professional strengths are, he or she won’t be effective in that company.

In many business circles, mastery is seen as heroic and hierarchical. Junior people or functional specialists are told to pay their dues by doing whatever is necessary to meet an impossible deadline. But the goal of collective mastery should not be to lean on the efforts of the young and the dedicated. Instead, collective mastery should ultimately allow the organization to achieve its remarkable outcomes by spreading the genius to a broader base of activity. If you can accomplish that, in a sustainable fashion, then you have a truly extraordinary culture.

Deploying Your Critical Few

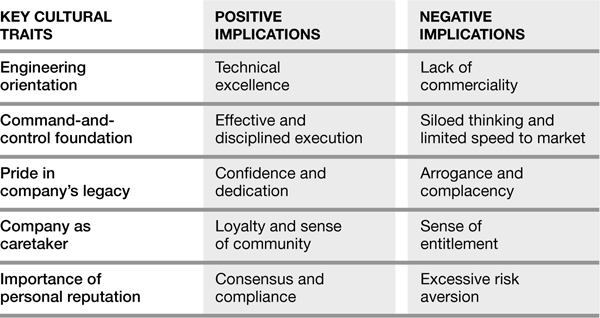

The temptation is great to blame your culture when the organization resists change. For not every aspect of your culture is positive. Indeed, the same attributes of your culture can have beneficial effects but also hold your company back. Figure 4-1 shows a few cultural traits that some companies have and the ways in which they manifest themselves.

FIGURE 4-1

Advantages and disadvantages of an organization’s cultural traits

As we suggested earlier in this chapter, many executives mistrust their culture. You may not believe that your company has the kind of culture it needs. Chances are, it has several subcultures operating simultaneously, often at cross-purposes. Sometimes, these are legacy cultures from acquisitions. Other times, the subcultures are tied to specific functions, with the mandates, priorities, and cultural values associated with a profession like IT, organization development, or sales. The enterprise’s overall value proposition may not have been clearly articulated, and people may not understand how their work fits with it.

If this sounds like your company, then your situation probably seems daunting. You can’t live with your culture, you can’t ignore it, and you can’t completely change it. What, then, can you do? You can find the parts of your culture that work in your favor and bring them to the fore. There may be more value in your culture than you realize at first. One way to accomplish this is through what we call the critical-few approach. It was developed by a team of people at our firm, led by long-standing culture expert Jon Katzenbach.16 The critical-few approach involves a small number of cultural elements:

•A critical few informal leaders: These people have the behavior you want to see more of, and you can enlist their help in spreading coherence through the company. They tend to be quietly influential, they can be strong allies in gaining coherence and guides to aspects of the system that you would not otherwise see.

•A critical few emotionally resonant traits: These traits are touchstones tied closely to the identity of the company. We’ve already mentioned many examples throughout this book: people’s dedication to “insanely great” products at Apple, to customer experience at Amazon, to relationships and products at Natura, to continuous improvement at Danaher, and to frugality and leadership by example at IKEA. Behind each of these few traits, there is a story that, like many of the stories recounted in this book, exemplify your company’s identity and why people should care about it.

•A critical few behaviors that you want to spread throughout the organization: These behaviors are ways of operating that, if everybody followed them, would help the company move forward. At CEMEX, one such behavior was the emphasis placed on closing the books on the first or second day of every month. “A lot of managers initially wondered why it was so important to do this,” recalls Juan Pablo San Agustin, executive vice president of strategic planning and new business development. “They thought nothing would be lost if they did their closings on the seventh or eighth day. But we believed that having that information readily available would increase the likelihood that managers would make the right decisions. And the practice had a very high-level overseer: [then-CEO Lorenzo Zambrano] into whose email inbox all of these reports flowed.”17

Other behaviors might include keeping all memos to a page; eliminating the formal committee meetings where the decision was already made in the corridor beforehand (“Let’s just have the ‘real meeting’ instead”); the inclusion of leaders from at least two separate functions for every decision made about a distinctive capability; or as former Campbell Soup Company CEO Douglas Conant once did, putting on running shoes and taking a slow walk around the grounds every day, always at different times. Knowing that he might be passing by, people got in the habit of striding along with him and raising candid questions. The critical behavior he wanted to encourage, after all, wasn’t walking; it was open conversation.18

Identifying Your Own Critical Few Elements

For each of these three questions, identify a critical few elements that you will bring to bear from your culture. Look for elements that line up with your identity: reflecting your value proposition and supporting the capabilities system you are building.

1.Who are your critical few informal leaders? There are two categories of people. Exemplars are role models, visibly exhibiting the set of key behaviors you want the organization to adopt. “Pride builders” are internal guides, helping you understand the culture. Both groups together should number no more than 5% of the total population of your enterprise. They are your advance guard: people who see the value of your company’s move toward coherence and who are prepared to help others make a commitment. They can also help you identify the attributes and behaviors in questions 2 and 3.

| Exemplars | Pride builders | |

| Where to find them | In roles identified as critical to building distinctive capabilities—especially those who have worked across functions to innovate or make point interventions that have added value | In roles “close to the work” with frequent opportunities to observe and influence colleagues—not necessarily through formal management positions |

| What they provide | Experience in translating tacit knowledge into concrete, everyday actions in ways that can be emulated by others | Insight into the reasons why people will come on board and ways to enlist their commitment |

| How they can serve your transformation | They act as visible role models, informally coach colleagues in similar roles, and participate (or lead) in blueprinting, building and scaling capabilities | They share practical ideas and provide feedback on the impact of the new capabilities system and the reactions of the culture |

2.What are the critical few traits you want to highlight? Identify a few key attributes that exemplify the best of your company’s culture. (These are often the distinctive qualities as described earlier in this chapter.)

| How to find them | What to look for |

| Ask people: conduct interviews with exemplars, pride builders, and leaders about the traits that characterize your company. | Pick traits that support the distinctive capabilities you are trying to build. For example, “empathy” in a health care or financial services company could support a new capability for designing support services that would help customers make better decisions. |

| Listen for stories: in formal gatherings or informally, seek out people who can recount the experience of building the new capabilities. | Pick stories of challenge, in which the company faced a difficulty in developing the capabilities it needs—and overcame that challenge. |

| Go back in time: surface historical perspective that is relevant now. | Look in your company’s history, as we saw Adidas doing in chapter 3, for antecedents to the capabilities you are building now. |

| Look for artifacts: find objects that represent the aspects of culture you seek to promote. | These artifacts can include architectural features (like Natura’s building), memos, product prototypes, old machines, reports, photos from key events, or anything else that symbolizes the link between strategy and execution in your company. |

3.What are the critical few behaviors that you want the organization to exhibit going forward? These are things that a few people do regularly now; and if everyone did them, they would help close the gap between strategy and execution. Assemble a list of ten to twenty behaviors and use the following checklist to winnow them down to three or four. Pick the behaviors that give you the most “yes” answers:

Having identified a critical few informal leaders, traits and behaviors, put them together with your capabilities system. For each capability, identify one or two behaviors that would make a difference. (The same behaviors can be used on more than one capability.) Create a rationale for each of these behaviors, using the attributes as a way to articulate them. Enlist your informal leaders to exemplify these behaviors and to help you convey their value to others throughout the enterprise.

Zhang Ruimin followed the critical-few approach at Haier when he introduced the idea of open innovation. He identified a trait: the company was full of people who spoke openly and candidly, especially when compared with managers at other Chinese companies. Or as he explains it, “A few people who have gone from Haier to work for other companies have written to me telling me that the biggest difference between Haier and their new company is Haier’s transparent interpersonal relations.” He knew therefore that at least some managers at Haier could handle it when he brought customers into their R&D process around 2012.

“When we started requiring that products be developed in cooperation with users participating in the front-end design … some [employees] flatly refused. Some were [passively] unwilling,” he recalls. So Haier started conducting design sessions with consumers with the Dizun and Tianzun air conditioner series, where there was a stronger interest in making this new type of customer engagement work. “We told our employees in these groups that it wasn’t a big deal if they failed,” Zhang says, “that it was meant to be a process of trial and error.” The groups turned out to be a great success, leading directly to several innovations, including smartphone-based controls and units that change color depending on the air quality in the room. This type of conversation is now becoming standard practice at Haier.19

The critical-few approach may seem simplistic, but its power comes from simplicity. It starts with the premise that you already have everything you need in your culture—it’s just not evenly distributed. Some people are already living the right behaviors, some traits are already taking you in the right direction, and some people are already worth cultivating. With the critical few methodology, you can accelerate your company’s movement to coherence. The resulting culture—a culture of emotional commitment, mutual accountability, collective mastery, and a number of other attributes unique to your company—will become a source of strength, if it isn’t one already.