20

![]()

Navigating the Political Waters

IN THIS CHAPTER, I want to cover how to work with your sponsor and other senior management and then move on to some of the negative aspects of company politics. In my experience talking to many project managers, the political landscape is one of the most frustrating aspects to deal with. I think part of the frustration stems from a lack of understanding of what is really going on, particularly as related to decisions made and actions taken.

The political landscape in most companies starts with the organization chart. The org chart defines who reports to whom and defines the relationships among people at a given time. However, that is only part of the story. The second half of the politics often relates to the individuals who occupy the positions on the org chart. This is where the informal hierarchy is established and affects who has access to information and when.

For example, in some companies I have worked with, the senior executive who oversees human resources is a very influential person in the decisions made by the CEO. In other companies I have worked with, the person in the same position is treated as if his presence is tolerated given the actions I have seen from others who would be equals on the org chart. So what is the difference, and how can a project manager use that to her advantage?

Trusted Advisor

The key to understanding the difference just described can be understood if you look at the concept of trusted advisor. If a person is seen as a trusted advisor, a key decision maker (in our case, the sponsor) turns to that person when seeking advice on solving a business problem. That is a different role from being an expert—in our case, an expert in managing projects. So let’s review the difference between an expert and a trusted advisor.

Merriam-Webster’s defines trust as a “firm belief in the reliability, ability, or strength of someone.”

It may appear to be a cliché, but a project manager’s relationship with the sponsor and with other senior stakeholders is built on trust. Trust is absolutely essential. That is one reason I continue to reiterate the point that you must never let your sponsor be surprised. If he ever is surprised, his trust in you is weakened, and he will begin to be on guard in dealing with you about the project.

Building Blocks of Trust

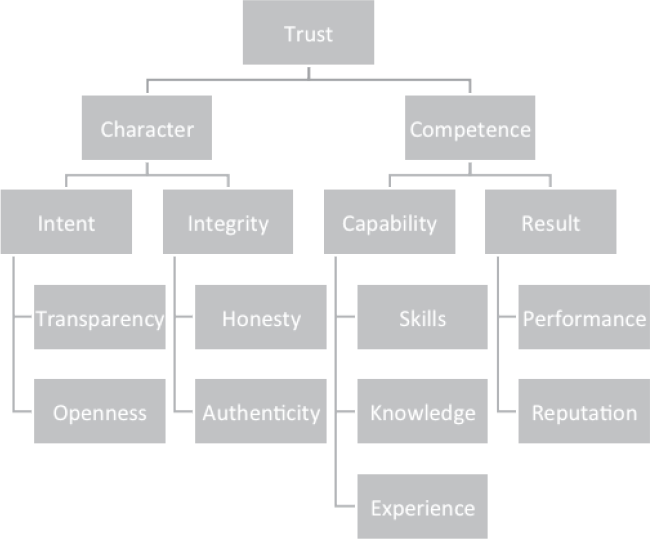

The building blocks of trust are built on four conditions:

1.Credibility: “I believe what you say,”

2.Reliability: “I can depend on you,”

Figure 20.1: Building Blocks of Trust Source: Adapted from Reyes Velasco.

3.Confidence: “I feel comfortable in discussing this with you,”

4.Personal Integrity: “I have confidence that you are honest and have moral principles.”

These four building blocks rest on a foundation, as illustrated in Figure 20.1. While all of these elements are important, my experience has taught me that transparency and performance are the two essentials for becoming a trusted advisor.

Emphasis on Solutions

A sponsor will begin to trust a project manager when the emphasis is on solutions. While we may need our sponsor’s assistance in solving a problem, it is important that we come in with not just a problem but with a proposed solution that the sponsor can actually help with. And it is important to remember that our sponsor may not have leverage over another executive to implement a solution. The sponsor may only be in a position to request the help of another executive.

As an example, I was working a project for the vice president of technology. Our project affected the company’s operations all over the world, and we were having difficulty in getting participation from one of the offices in Asia Pacific. In this situation, we knew what the solution was, but we needed the regional president to instruct his people to participate. In this situation, the regional president outranked my sponsor. This was a situation where company politics based on the organizational chart influenced what we could and could not accomplish. For reasons that even my sponsor never fully understood, the regional president felt that his operational goals took higher priority in his region, and he was willing to sacrifice the project implementation. In this project, our rollout was not as successful in that region. However, my sponsor was able to blunt criticism of the project with a detailed account of what we had requested, why we had requested these actions, and the response we received.

Keep the Business Goals Front and Center

Back in Chapter 1, I explained the process utilized, at a high level, that sanctions our projects. The project’s approval means the management team decided to wager the company’s money on achieving a business goal. Sometimes in a project with a long duration, the business climate or situation can change. We must always be mindful of that and make adjustments to the project to account for those changes. Nevertheless, don’t attempt to make these changes without thorough consultation with the sponsor. Often the sponsor has additional information that we have not been privy to know. Just asking the question and seeking guidance gives the sponsor confidence and boosts your profile as a trusted advisor.

Receiving Top Cover

I worked for many years with project managers who were Air Force veterans and described the protection they received from their sponsor as “top cover.” It was a term used in the Air Force to describe how aircraft were used to protect the infantry on the ground during combat. I think “top cover” is an appropriate term for the type of support we are looking for from our sponsor.

In my experience, the sponsor can provide top cover if you have worked with him as suggested in this book. The strategies and tactics I have outlined have allowed me to receive that kind of support. It also means being a trusted advisor on the project.

Having said that, even a great sponsor cannot avoid some aspects of projects. For example, I was doing a project for the chief technology officer of the company. The project was related to processes and procedures regarding how projects were sanctioned and implemented. I thought there could not be a better sponsor than someone from the C-suite. However, he has a boss too. About two months into the project, the CEO came to my sponsor and demanded a budget cut for all projects. Unfortunately, since this was the technology department, and my project was not related to actual technology, it was cancelled along with some others that did not make the priority list.

Negative Aspects of Company Politics

Unfortunately, we need to guard ourselves and our projects from the negative aspects of company politics as much as possible. These types of aspects are also referred to as hidden agendas. Some negative aspects are:

![]() Rumors.

Rumors.

![]() Games.

Games.

![]() Manipulation.

Manipulation.

![]() Alliances.

Alliances.

Let’s take a look at each of them, and I will try to give you advice based on my experience.

Rumors

We tend to think of rumors and gossip about others and their personal or private affairs. That is certainly true. However, some people use rumors to discredit a project, its sponsor, and its project manager. The reasons vary, but it usually involves people who believe that rumors can help them meet their personal goals for advancement at the expense of others.

If you think about the environment mentioned in the very first chapter, remember that at the executive level, these people sit at the top of a large pyramid. Just because they made it to the C-suite does not mean they have lost their ambition. Individuals may be competing with your sponsor, for example, to replace the CEO who is due to retire in the next three years, and people might be already positioning themselves to make a run at the position.

I have found that the best way to combat gossip and rumors is to have a strong and correctly targeted communication plan. It is very difficult for individuals to cast doubt on what is or is not happening in the project if the people who count are well-informed.

I would also suggest that you have a good network in place to provide feedback on any gossip that might be circulating. Address those rumors immediately, and try to pinpoint the source of the gossip. I would also recommend you inform your sponsor if you find the source. That information is useful to your sponsor because the person who began the rumor may not have been the actual source and may have been just passing on “information” heard from the executive boss. Recognizing the source can help your sponsor to be guarded in dealing with the other executive.

Games

To understand this type of office politics, think of it as a series of games. The place to start is to attempt to understand the perceived payoff. Project managers are sometimes guilty of games. An example of that game might be characterized as the No Bad News game. The project manager does not want the sponsor to get upset, so she suppresses any negative news about the project. Of course, sometimes that works, and things get sorted out before the sponsor becomes aware of problems. Usually, however, things continue to be negative, and the project manager has now damaged the trust the sponsor has in her.

Other games may be related to the changes your project is bringing to the company after implementation. Often, those who were responsible for the legacy system, process, or procedure are not happy, and they resist the new way of working. This executive may start playing games because he feels it threatens his power base within the company. In this situation, having a strong, comprehensive change management plan is essential. A change management plan that illustrates the benefits to the individuals involved in the work, including a strong training component, can overcome the game.

Manipulation

Often at the root of office politics is manipulation. In this case, others are determined to undermine the project. An example is where an executive has promised to provide technical resources to your project team but does nothing to create space in the person’s workday to allow that participation. Some dedicated individuals will attempt to work two jobs—their day job and the project work—but make no mistake, a person’s day-job responsibilities will always trump any promised work on the project. Again, look for the potential payback the manipulation might bring. You and your sponsor need to put together a strategy to end this behavior, and then you need to track the mitigation approach in your risk register.

Alliances

In any organization—and companies are no exception—natural alliances occur. One of the strongest ways to combat the politics is to observe who is in an alliance with your executive sponsor. You may or may not want to actually discuss this aspect until you have become a trusted advisor. However, you can carefully observe and listen to your sponsor as he discusses other members of the management team.

You will begin to pick up on whom your sponsor admires and who admires him. These alliances can be very important in dealing with the other negative aspects I have discussed. In a project I was leading where politics were particularly brutal, I uncovered the alliances my sponsor had forged—and those executives that he was not fond of. My sponsor and I built a very comprehensive engagement plan for those allies and a different but still robust communication plan for the antagonists. It worked, and my sponsor later ended up as CEO of the company.

Points to Remember

![]() Work very hard to become a trusted advisor.

Work very hard to become a trusted advisor.

![]() Maintain an emphasis on solutions.

Maintain an emphasis on solutions.

![]() Keep the business goals front and center at all times.

Keep the business goals front and center at all times.

![]() Be vigilant for office politics, and have a plan for mitigating those risks.

Be vigilant for office politics, and have a plan for mitigating those risks.

![]()