3

Developing Strategy and Tactics

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Establish strategies for attaining your objective in negotiations.

• Change strategies as negotiations proceed and circumstance dictates.

• Devise effective tactics for pursuing your strategies.

The third phase of prenegotiation deals with the question, “How can I convince the other side that the approach that is best for me is the most favorable for everyone concerned?” Skilled negotiators tackle this matter by adding effective and appropriate strategy and tactics to their prenegotiation plans. These will be designed to help them reach an objective that may be very different from that of their opponents.

DEFINING STRATEGY AND TACTICS

Strategy and tactics are familiar words with rather special connotations when used in connection with an effective plan to gain a specific objective. It is interesting that each is somewhat dependent on the other—good strategy and poor tactics result in the same degree of failure as do good tactics and poor strategy.

The dictionary defines strategy as “skillful management in getting the better of an adversary or attaining an end.” Tactics is “the mode or practice for gaining advantage or success.” So we may interpret effective strategy as a broad, long-range approach that is implemented by a series of planned tactics. In the eyes of the negotiator, tactics are the steps by which his or her strategic plan moves purposefully toward an objective against the opposition of the other side. How simple the process of negotiation might be if the other side could not be counted on to have a plan, strategy, and tactics of its own!

STRATEGIES FOR ATTAINING OBJECTIVES

It is obvious that the basic objective of any negotiation is to move forward and improve upon one’s original “ground zero” position, giving as little as possible at every step along the way. Just as obviously, the method of doing this cannot remain static but must vary with current conditions. Effective strategy will take into consideration:

1. The reasonableness of the objective.

2. The availability of alternatives.

3. The availability to shift the strategic game plan if the original objective becomes less significant than initially thought.

4. Ways to shift the planned strategy if an unyielding stand is encountered. An effective strategic game plan has the flexibility to exploit the paths of least resistance rather than to continue on a self-defeating course.

Changing Primary Strategies

Effective strategy cannot be static. Or, to put it another way, “If at first you don’t succeed,...” try a different strategy.

Some of us seek to borrow money for business or personal purposes when the money market is tight. To do it, we would probably employ more finesse and develop our approach more carefully than when money is plentiful. This extra persuasiveness is also the proper approach when we are competing against other candidates for a desirable position or seeking to sell our product in a market where many companies are equally qualified to deal. Let’s amplify the loan example.

Case 1

The money market is tight and our objective is to obtain needed funds. The strategy we use is to convince the prospective lender that his or her funds, while limited, can be put to best use by considering the interest or repayment schedule we are willing to offer. Such a strategy forces the lender to consider our terms rather than place undue focus on his or her limited resources. “After all,” we say, “there are other lenders in the market and I can borrow elsewhere if necessary.” By using a statement like this, tactics are brought into play.

Case 2

The money market is flexible and our objective is to obtain needed funds. The strategic approach we use is altered. “I would rather deal with you because I am convinced that you understand my needs.” It is unimportant whether the statement is completely accurate or not. The significant point is that the objective has been enlarged to provide an element of future protection. If the money market tightens up later, the lender can be reminded of the borrower’s earlier concession in deciding to deal with X instead of X’s competitor.

In these simple examples, we see that the same objective can require changes in the primary strategic thrust to meet circumstances that exist at the time bargaining takes place. The picture does not change when the opposition raises alternative issues during a negotiation. A strategy that is properly prepared allows for tactical shifting of gears in so smooth a fashion that the alteration goes unnoticed by the other side.

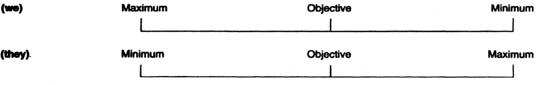

Each side has an objective that involves a maximum and a minimum position. This is illustrated in Exhibit 3–1. Notice that the “we” and “they” objectives are not aligned. As used in this context, objective equates to target, that is, the point at which the conclusion of the negotiation will be in your favor. This pattern is typical and has bearing on negotiation strategy—to move the opposition closer to your objective than they can move you to theirs.

Notice also how the “we” maximum (the highest we are prepared to go) corresponds with the “they” minimum (the least our opponent will accept). On the other end of the line, our minimum is less than their initial asking price, knowing that it is higher than they can realistically expect to get. This type of situation is commonly found in personal or business transactions, salary increases, and the like. As negotiations progress, the opposition’s minimum position should be uncovered, but it will take sound strategy and tactical know how to bring it out.

Deductive Strategies

During the prenegotiation period, the more that is known about the item to be obtained, along with the worth of successfully completing the transaction, the stronger will be the bargaining position. In this context, worth is equated with need rather than value. For example, the worth of a job in terms of prestige and chances for advancement may be more important to the individual than the salary that goes with the job.

It is important to develop an effective means of narrowing the gap between the “we” and “they” objectives. This can be done by using deductive strategies. For example, a specific acquisition is needed for personal or business purposes. Resources that are adequate to attain it are available within your objective range. In this situation, the gap does not exist for practical purposes. The ready availability of resources has eliminated it, but you may want to improve on your objective by negotiating a still more favorable position. This type of situation presents the strongest bargaining position.

Another example of using deductive strategies would be if the negotiator has a specific requirement but lacks the asking price, although extra money could be located if absolutely necessary. In this case, the negotiator works to get the seller to lower the price, or to have the seller move his or her objective closer to the seller’s minimum. The negotiator can do this by countering with a lower price and meaningful reasons why the asking price is out-of-line with the worth of the item to the buyer.

Any counteroffer must be capable of a realistic and reasonable defense; otherwise it will be refused out of hand and the credibility of the negotiator will suffer. Provided the counteroffer is within the seller’s objective range, movement toward the seller’s minimum point can be expected.

From the outset, the negotiator is aware that the resources available are far below the asking price but still within reach. Using deductive strategies, the negotiator takes the initiative, offering a figure much lower than that asked.

In a real-estate transaction, for example, the negotiator may suggest that the seller finance the sale. The seller can be expected to refuse initially. His or her objective is to unload the property and get all the money promptly. At this point the negotiator outlines elements of the proposal that have special appeal: The seller, in taking the negotiator’s deal, will earn a fair return in an innovative way. The seller will earn a high rate of interest over an extended period, plus a lien against the property. “Where else can you invest at such a high rate so safely?”

In this example, the negotiator substantially improves his or her chances of bringing the opponent’s objective, selling the property at the best price, more in line with the negotiator’s objective, buying the house for less in cash.

SUCCESSFUL TACTICS

Successful tactics are those with which we are entirely comfortable. Negotiation is a part of daily life for all of us. If we are wise, we bring as many of our strengths to bear in formal negotiations as possible and sharpen and channel them through study and experience at the bargaining table.

In the prenegotiation stage, there are several tactics that should be included as part of any broad strategic outline:

1. Avoid changing a planned approach unless change is absolutely necessary. However, don’t continue a line of attack that has failed; be prepared to shift to a new tactic.

2. Employ moderation and avoid initial confrontation.

3. Keep a line of retreat open. Not only is this a face-saving tactic, it also provides necessary flexibility for dealing with shifts by the opposition.

4. Always leave a line of retreat open for your opponents. This will provide them with an incentive to agree if your tactics shake their conviction about the reasonableness of their position. A concession is much easier to attain than a surrender.

5. Avoid a frontal attack unless your bargaining position is definitely stronger than your opponent’s.

Tactics employed by a negotiator who has methodical habits and attitudes probably should involve generous use of supporting data presented in a planned and sequential manner. There should be a logical progression from a known factor at the beginning, such as selling price, to the conclusion.

Specifically, a bargainer of this temperament might make extensive use of direct statements. Arguments would be presented in such a way that an opponent would appear unreasonable in declining to concede the correctness of each point made.

After the negotiator has gotten agreement on the first issue, he or she will take the opponent a step closer to the ultimate objective by the same logical means. This advantage will be followed up by moving the discussion a step closer still until, finally, the opponent either must agree on every point or retrace the entire line of tactical succession.

This can tend to force the opponent to make such statements as, “That’s not what I meant,” or “You’re putting words in my mouth,” which indicate a defensive and weakened position highly exploitable by the negotiator.

When an opponent employs this approach, the most effective parry is to use simple questions to avoid agreement. Questions break the opponent’s chain of logic and require a pause to respond. The interruption provides the negotiator with an opportunity to inject a new topic of his or her choosing.

OFFENSE AND DEFENSE

Tactics for the negotiator who has an active, quick mind involve using a rapid-fire series of facts presented in such a way as to allow an opponent little time to think before responding. The idea is to overwhelm the opponent with lightning thrusts. A successful parry to this tactic is to slow the opponent by requesting clarification. Statements such as, “I don’t understand your point,” or, “I’m sorry, would you repeat that, please,” interrupt the barrage. Here again, the negotiator can take the offensive by using the interruption to initiate a new line of approach.

In formulating tactics, note that the one who initiates the negotiation always takes the offensive—simply by starting off. For example:

Case No. 1

“Boss, I’ve been here a year and you have indicated that my work has been satisfactory. Now I think it’s time we talk about raising my salary.”

“I’m sorry, but the painting job you did for me was worse than I could have done myself. Either redo the work or I’ll pay you for only half the job.”

In these examples, the boss and the painter must defend a position already established in the opening statement:

Case No. 1

“As a matter of fact, Joe, I’ve been meaning to go over the sales figures for the last quarter with you, and now is as good a time as any.”

Case No. 2

“Mister Smith, you said that I shouldn’t spend all week on the job. I only did what you wanted.”

With these rejoinders, the original attacker becomes the defender—and so it goes. As the negotiations progress, the defensive pattern illustrated is difficult to avoid, but prenegotiation planning and preparation can be structured so as to ensure that the typical pattern does not result in an endless series of charges and countercharges.

Case No. 1

“Boss, my sales have been up, as you can see by your own figures. Based on the revenue my efforts have provided, I have more than earned a fair and reasonable increase.”

Case No. 2

“A professional painter would not require more than two days to paint this house. You are a professional painter, so I will pay you for two days’ work.”

STRONG VERSUS WEAK POSITIONS

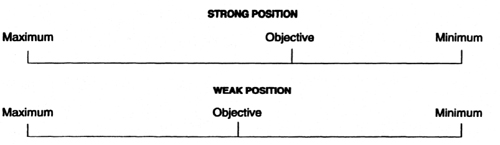

Strength and weakness are not only relative, they represent states of mind. This is not to say that actual differences in initial positions do not exist. The statement means simply that the negotiator who is prepared to win is more likely to do so. This has been established by experiments conducted by Chester L. Karrass and described in his research. The initial positions of strength and weakness can be diagrammed as illustrated in Exhibit 3–2.

Notice in the strong position that the objective is at the lower end. The person negotiating from strength will tend to set his or her objective closer to the acceptable minimum than will the negotiator in a weak position. A well-prepared negotiator will not require much time to determine with reasonable accuracy how much confidence, and therefore strength, the other side has in the merits of its initial position.

During the period of prenegotiation activity, plan the strategy and tactics which will assure that you retain the initiative.

As negotiations progress and movement begins to be apparent, the initiative is retained by using preselected tactics. Such tactics are enhanced through understanding the psychology of negotiation and the appropriate techniques to be employed.

Strategy is defined as skillful management in getting the better of an adversary or attaining an end. It may also be defined as a broad, long-range approach that is implemented by a series of preplanned tactics.

Tactics are defined as the steps by which the strategic plan moves purposefully toward an objective against the opposition of the other side.

Effective strategy takes into consideration a reasonable objective, the availability of alternatives, the ability to shift from primary to secondary objectives, and the flexibility to exploit lines of least resistance. The principal purpose of strategy and tactics is to move opponents closer to your objective than they can move you to theirs.

• Five tactical approaches that should be included in a strategic negotiation plan are:

1. Avoid changing a planned approach unless change is absolutely necessary.

2. Avoid making a frontal attack.

3. Employ moderation and avoid an initial confrontation.

4. Keep a line of retreat open for yourself.

5. Leave a line of retreat open for your opponent

One effective method of negotiating is a step-by-step progression through a series of logically connected positions, each supported by generous amounts of data, and each seeking agreement from the opponent before going on to the next.

The party initiating a negotiation always takes the offensive. An effective parry to a barrage attack by an active, aggressive negotiator is to ask questions requiring clarification. Attitude is important: The negotiator who is prepared to win is more likely to do so.

Review Questions

Review Questions

1. Counter offers need not be realistic to be effective. |

1. (b) |

(a) True |

|

(b) False |

|

2. Generous use of supporting data presented in a preplanned, sequential manner indicates that the negotiator is probably a(n) _________ person. |

2. (c) |

(a) active |

|

(b) impulsive |

|

(c) methodical |

|

(d) aggressive |

|

3. When negotiations start, the host usually begins by questioning the position of the guest and thereby assumes the initial _________position. |

3. (b) |

(a) defensive |

|

(b) offensive |

|

(c) strategic |

|

(d) tactical |

|

4. The person who is most likely to win in negotiations is the one who is: |

4. (c) |

(a) determined. |

|

(b) educated. |

|

(c) prepared. |

|

xhibit 3–1

xhibit 3–1