Selected Readings

NEGOTIATING IN ANY LANGUAGE; How NEGOTIATIONS WORK

Have more than thou showest, speak less than thou knowest.

The subject of negotiations is both timely and timeless. It is timely because almost everything about our society in general, and our workplace in particular, is increasingly complicated. Today there is more litigation, more cultural diversity, more regulation, more technology, and—in line with the focus of this book—more globalization among businesses. The subject is timeless because life is a series of endless negotiations.

Moses, for example, was more than an Old Testament prophet. He was an ace negotiator. He had been up on the mountain all day negotiating the Ten Commandments with the Supreme Other Side. His buddies asked, “Hey Mo, how’d it go?” “It was rough up there today,” Moses answered, quite exhausted. “The good news is I got Him down to ten. The bad news is adultery’s still in there!”

Certain fundamentals of negotiations apply whether you are negotiating in Tulsa or Bombay. It is important to understand these fundamentals: They are the foundation on which you will later build your international negotiating strengths. These fundamentals include understanding the concept of negotiation, appreciating the importance of the win-win approach, understanding the stages of negotiation, being able to plan your negotiation, and knowing what it takes to close a deal.

In many ways, the negotiating skills we seek to master are those you practiced as a child but forgot as you became older and more sophisticated.

Anyone with a six-year-old is reminded of this on a daily basis. Children are excellent negotiators because:

• They are persistent.

• They don’t know the meaning of the word no. They know that when we say no, we often mean maybe.

• They are never embarrassed.

• They often read us better than we read them.

Let’s begin relearning these skills by defining our subject.

NEGOTIATION DEFINED

Negotiating is the process of communicating back and forth for the purpose of reaching a joint agreement about differing needs or ideas. Negotiating has to do with persuasion rather than the use of crude power. What’s more, negotiation has to do with the other side feeling good about the outcomes of the negotiation. As such, negotiating is a collection of behaviors that involves communications, sales, marketing, psychology, sociology, assertiveness, and conflict resolution. Above all, it has to do with the clear understanding of our own motivations and those of the other side as we try to persuade them to do what we want them to do. A negotiator may be a buyer or seller, a customer or supplier, a boss or employee, a business partner, a diplomat, or a civil servant. On a more personal level, a negotiator may be your spouse, friend, parent, or child. In all these cases, your negotiating skill strongly influences your ability to get ahead in both your organizational life and in your other interpersonal relationships.

Some negotiations involve business counterparts outside your organization, while some involve those within your organization, such as the boss, top management, attorneys, accountants, and other technocrats. With both internal and external situations, the main objective of a negotiation is to help you get what you want.

Since the focus of this book is international business negotiations, we refer to our counterpart from a foreign culture as TOS (The Other Side). TOS can be a negotiating counterpart in a foreign country (or host country) where the negotiation is taking place or a negotiator visiting the United States to do business with you.

What Can You Negotiate About?

Though the details of business negotiations can be quite complex, there are really only six subjects about which you can negotiate. Everything else is a

variation on these themes:

1. Price

2. Terms

3. Delivery

4. Quality

6. Training

THE IMPORTANCE OF WIN-WIN

Almost any book about negotiating written since 1980 includes great tributes to the virtues of win-win negotiations. This means that both you and TOS win in the negotiation. After having conducted seminars on negotiating with thousands of participants around the world, I can tell you that virtually every individual is quick to agree publicly with the idea of win-win negotiations. Yet in real-life—particularly in the United States—negotiations are often conducted with an “I win, you lose” type of behavior. Intellectually, we know that the cool, even-handed, win-win approach is appropriate, but this is sometimes difficult to remember when the heat is on.

You might ask, “What’s so bad about win-lose negotiations as long as I make sure that I’m not the loser? I mean, I’m under a lot of pressure, so if the other person bleeds a little, this is not one of my life’s great problems. It’s nothing personal, but I’m not in the charity business.” So we put our foot right on the other person’s neck and proceed with the negotiation.

The problem with win-lose negotiations is this. The loser usually behaves quite predictably and tries to get even. The loser’s thinking goes something like this: “I’m going to get you. It may not be today. It may not be tomorrow, but I will get you. You will bleed and not even know it.” Losers usually wind up pouring much of their energy into all kinds of dysfunctional behavior, aimed at getting out of the losing position. Sometimes the result is even lose-lose. The air traffic controllers’ strike early in President Reagan’s first term is an example of a win-lose negotiation that ended up lose-lose. The workers lost their jobs, the union went out of existence, and the public was denied trained air traffic controllers. Given the outcry from some members of the public, it is a matter of debate as to whether President Reagan was a winner or a loser in this situation.

You can see much evidence of win-lose problems on the geopolitical level. The conflicts that have been sustained for decades, or sometimes even centuries, are really unresolved conflicts from previous win-lose situations. The Middle East antagonisms are a good example—a series of situations where the various parties have sought to “win” only at the expense of TOS.

Win-win negotiation is critical, not for you to be a wonderful, kind human being, but because it is the practical thing to do. It will help you get more of what you want. And how is this achieved? In two key ways:

1. Meet the needs of TOS (The Other Side). Switch to the frequency that others can tune in to, which is known as WIIFT (“What’s In It For Them”). The idea here is that we can get much of what we want if we help others get what they want.1

2. Focus on interests and not positions. Positions are almost always unresolvable, but finding out interests helps you assess the real needs of TOS.2

It’s like two people fighting over an orange. “I want the orange,” says one. “No, I want the orange,” says the other, and a win-lose confrontation ensues. With enough patience and empathy, you might find out that one person wants the fruit of the orange to eat, while the other person wants the peel to make marmalade.

It is sometimes difficult to establish a win-win framework in a domestic business negotiation, even when one has honorable intentions. Your counterpart may doubt your sincerity, or the condition under which you are negotiating may not lend itself to a feeling of collaboration and mutual trust. Achieving a win-win outcome can be especially difficult, however, in global business negotiations. The different cultural backgrounds of negotiators may cause them to bring different expectations to the bargaining sessions, create stereotypes of TOS, and develop a climate of suspicion or distrust.

Thousands of such examples abound in international business negotiations. Achieving win-win negotiations, and tuning in to WIIFT, takes an enormous amount of empathy, understanding, listening, patience—and skill. A California-based distributor of computer software relates the frustration she felt during her first trip to the Pacific Rim. “I left California for ten days to accomplish some fairly routine business in Japan and more complicated business in Singapore. I knew that business takes longer in Japan than in the United States, but I had no idea it would take several days to really get down to business in Tokyo. The tone of the negotiation was very bad because I really felt they were dragging their feet.” The situation changed in Singapore. “I was equally surprised to find that in Singapore I was in and out of there in no time. Things got off to a bad start because I felt I should make small talk—I’d been doing it for five days in Japan—and I think the Singaporeans felt I was being evasive and not really wanting to move ahead on the deal. I finally convinced them that we had the same objectives. I had scheduled five days there, but I needed only a morning. The Singaporean buyers wanted to talk business as much as I did. After a nice lunch with them, I headed for the airport, mission accomplished.”

WIIFT for the Japanese negotiators in this case was patience on the U.S. negotiator’s part, patience that indicated interest and respect for the long-term relationship. WIIFT for the Singaporeans was different. They were looking for the U.S. negotiator to demonstrate interest by moving along crisply in the business deal.

THE STAGES OF NEGOTIATION

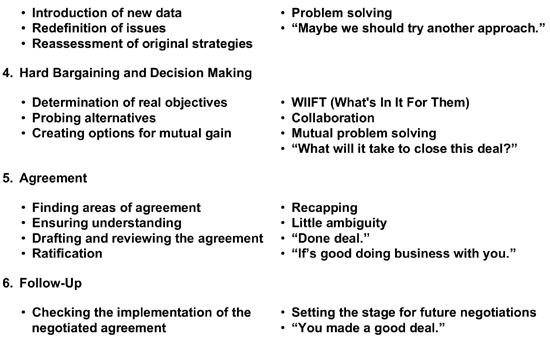

In both domestic and international negotiations, there are six stages through which negotiations proceed: (1) orientation and fact-finding, (2) resistance, (3) reformulation of strategies, (4) hard bargaining and decision making, (5) agreement, and (6) follow-up. Knowledge of these stages helps you understand the overall shape of the negotiating process and gives you a bearing as you proceed through each negotiation. Here is a summary of the six stages:

Orientation and Fact-Finding

This first stage is critical for what is to come in the negotiations. The saying “information is power” is never more true than in the early stages of the negotiation process. The more information you can obtain here, the bigger the dividends will be in the negotiation’s later stages. Unfortunately, many U.S. negotiators pay little attention to this critical stage of the negotiation. Orientation and fact-finding should begin even before one sits down with TOS. Orientation may mean learning about the organization of TOS, the history of similar negotiations with TOS, or the individual styles of your counterparts. Does the organization have a good reputation? Are there any recent management shake-ups? How much power do you think your negotiating counterpart has within his or her organization? How are negotiating issues to be addressed: individually, or as a group? How important will a written contract be? Are these people generally easy to do business with? And why is this the case or not the case?

There is a misconception in the American culture that “what you don’t

know can’t hurt you.” In business negotiating, what you don’t know can kill you.

Resistance

This can be a painful, if predictable, part of any negotiation. Indeed, TOS is usually not devoted to showing you a good time. Don’t be upset by the resistance you encounter in the negotiation. In fact, if you encounter no resistance, this could be a signal that there is little genuine interest in meaningful negotiations. As long as there is resistance, there is interest, and knowing the source of the resistance allows you to work on overcoming TOS’s objections. To break through this resistance, we must again tune in to the frequency that TOS can understand: WIIFT—What’s In It For Them. This means finding ways to meet the needs of TOS. Here are typical reasons why you may encounter resistance from TOS:

• Logic: “Your price is too high.” “We need it sooner.”

•Emotion: “I really don’t like doing business with these people.” “This guy is obnoxious.”

• Change: People are usually more comfortable with predictable, familiar situations than the changes you want them to adopt, such as a different product line or price.

• Testing your limits: “How far is this person willing to go?” “Is this really her bottom line?”

• Organizational constraint: A budget, policy, or boss overrules TOS’s decision.

• Personal rule: No concessions will be made at the first meeting.

Reformulation of Strategies

You develop negotiating strategies when you plan the negotiation. As you gain new data, it is important to reassess earlier strategies. What is the motivation of the parties to do this deal? What strategies worked? What didn’t work? This is the time to put your creativity and ingenuity to work.

Hard Bargaining and Decision-making

Concentrate on the real needs of both sides, not just on the formal positions being taken at the negotiating table. Here you concentrate on the determination of real objectives. What are TOS’s main objections? How can they be overcome? What are the key issues involved? Determining WIIFT becomes critical. Here is the time to invent options for mutual gain that will result in a win-win outcome.3

Agreement

Here you work out the details of the negotiation and ensure understanding. The negotiators ratify the agreement with their respective sides. In your case, ratification may be by your boss, attorneys, or financial management.

Follow-up

This stage is often forgotten by US negotiators. We work hard to sign the contract, then it’s adios, au revoir, syanora, arrivederci —I’m outta here. But by effective follow-up, you set the stage for the next negotiation. Use this follow-up as an opportunity for relationship building. Be sure to remind TOS that they made a good decision in negotiating the agreed-upon deal.

Exhibit SR–1 outlines the stages of negotiation and the activities within each of these stages. Note that there are both task (or content) issues and relationship (or process) issues in each stage. The content issues have to do with logic or facts, while the process issues have more to do with emotions and feelings. For example, the task aspects of Stage 1, Orientation and Fact-Finding, are to introduce the parties to the negotiation and to define the negotiating issues. The relationship aspects to Stage 1, however, include setting the climate for the negotiations and building rapport with TOS. It is important to address both task and relationship issues in order to have a successful negotiation.

PLANNING YOUR NEGOTIATION

Intellectually, U.S. negotiators know that proper planning is important. Practically, however, many American negotiators would rather take a beating than write a business plan of any kind. This resistance stems from three negative fantasy scripts: (1) “Someone might actually hold me responsible for this plan”; (2) “Once I write it down, I can’t change it”; and (3) “I know what I want to say, but I just can’t say it.” None of these fantasies need be true. With regard to No. 3, psychologists tell us that when we have this script, we in fact don’t know what it is we are trying to say, and trying to write it down can make this painfully clear. Planning your negotiation means doing your homework Without this vital preparation, you will concede the power that comes from making informed business decisions.

Planning your negotiation is a straightforward, four-step process that must be applied to both your side and TOS. For both sides, you must: (1) identify all the issues; (2) prioritize the issues; (3) establish a settlement range; and (4) develop strategies and tactics. Let’s look at each of these steps in detail.

1. Be sure to identify all the issues you can think of for both your side and TOS. Brainstorm the issues with your colleagues—aiming for quantity, not quality—to compile your lists. Be post-judicial, not prejudicial, in this process, thereby allowing a free flow of ideas from you and your negotiating team or other relevant players. The idea is to get a long list of every issue that could arise during the negotiations, for both your side and TOS.

2. Prioritize the issues for both sides in the negotiation. This will, or course be an estimate as to the priorities of TOS. Don’t worry about perfection. The key point is to start thinking in terms of TOS’s needs.

3. Establish a settlement range, defining the areas within which agreement is possible:

• Maximum supportable position. The agreement that you want under ideal conditions, and to which some degree of logic can be attached.

• What I’m really asking. The agreement you really want.

• Least acceptable agreement. The agreement that can be accepted if the going gets really rough. Your bottom line.

• Deal breaker. The condition under which an agreement cannot be reached. This can be one dollar less than the least acceptable agreement.

Settlement range is discussed further in the next section.

4. Develop strategies and tactics that help you achieve your goals and that meet the needs of TOS. Strategies determine the overall approach your side plans to take, while tactics are the actions you will take to carry out your strategy.4 Strategies may include which of your priorities you choose to emphasize and the overall emphasis you give to each of the subjects being negotiated.

Tactics are sometimes viewed as having to do with being manipulative, playing games, or having a hidden agenda. That is not the intent here. Rather, tactics are meant to be the “how to” part of achieving the overall negotiating strategies. Tactics may include whether or not to make the first offer, how much to offer, when to make concessions, and the speed at which you plan to make concessions. Many strategies and tactics are discussed in this book—not for you to be manipulative, but rather for you to avoid being a victim and to be aware of manipulations. In order for a negotiating subterfuge or “game” to be successful, TOS needs a victim—some poor slob who doesn’t know any better. For example, TOS may ask for your airline ticket when you first get to Yokohama in order to help you with further flight arrangements. This may be an act of courtesy on the part of TOS, but it also provides TOS with valuable information on pacing the negotiations. They know you will be there for eight days, piling up large expenses, and if they can be patient, you will probably be willing to agree to almost anything come the eighth day if little progress has been made. (There are many American negotiators who have found that little content was discussed until the ride back to the airport.) In this case, be alert to TOS’s game and avoid being a victim by trying not to be specific about return travel plans and being aware that TOS’s patience is putting you at a disadvantage.

We have been unabashed at saying that if anybody comes at us with

abusive or manipulative tactics, we will beat the living hell out of them.

John Bryan, Chairman, Sara Lee Corporation5

Let’s return to the issue of the settlement range, since you will be operating within it throughout the negotiation.

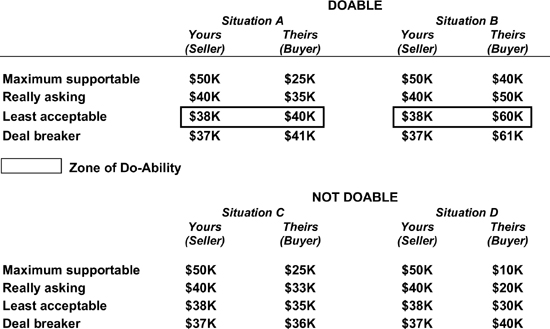

THE ZONE OF “DOABILITY” WITHIN THE SETTLEMENT RANGE

Is the negotiation doable? That is, is a successful conclusion of the negotiation possible given your settlement range and that estimated for TOS? The answer is yes if the settlement ranges overlap. In terms of the planning steps just discussed, the zone of “doability” is the area of agreement that is possible when the least acceptable amount is less or equal for the seller compared to the buyer—in other words, if the seller will accept an amount less or equal to that which the buyer is willing to pay. For example, if a seller will accept $20,000 for a concrete block machine, and the buyer is willing to pay $21,000, then the deal is doable. Exhibit SR–2 illustrates negotiations that are doable and not doable. In Situation A, there is a range of doability of $2,000 (between $38,000 and $40,000). In Situation B, this range is $22,000 (between $38,000 and $60,000). Anything beyond the least acceptable amounts is not doable because that would be a deal breaker. Situation B should be particularly doable because the buyer is really asking even more ($50,000) than the seller is really asking ($40,000) for this product or service. Neither Situation C nor D is doable because the seller is asking more than the buyer is willing to pay (unless, of course, one of the parties can be convinced to change his or her settlement range).

Remember, establish your settlement range and then estimate the settlement range for TOS. Will you guess wrong sometimes? Of course. The key point here is not one of precision but of empathy and understanding. It is critical to get in the mind-set of thinking about the needs of TOS, of what they may be after. You can always readjust your estimate of TOS’s settlement range with new information from the negotiation.

There are two important rules for effective use of the settlement range. First, prepare your settlement range before the negotiation. Second, have a logical reason for moving from your “maximum supportable” position to your “really asking” position and so on through the range. Let’s look at these two rules.

PREPARING THE SETTLEMENT RANGE PRIOR TO THE NEGOTIATION

You must decide your settlement range before the negotiation takes place. This is important for one key reason: to help prevent you from making concessions you might not have wanted to make had not the pressures of the moment been so great during the negotiation process. This is particularly true in international negotiations. For example, let’s say you have been in Jakarta for three weeks and have a perpetual stomachache; the work is piling up on your desk back at the office; and your boss wants to know the holdup on the deal. Meanwhile, you’re a week late in negotiating another agreement, your travel expenses are beginning to look like the national debt, your friends at home have found a permanent replacement for you on your softball team, and your significant other hasn’t exactly shown the greatest compassion in the world for your plight. It would be very tempting at this point to make a deal simply to get on with your organizational and personal life. Developing a settlement range helps keep you focused when these types of pressures mount

ESTABLISHING CREDIBLE REASONS FOR MOVEMENT WITHIN THE SETTLEMENT RANGE

Skilled negotiators offer reasons as to why they are moving within the settlement range. Otherwise, the negotiators are simply bantering out respective positions, with no credibility attached to their positions. Does this sound familiar?

Seller: My best selling price is $100 per unit.

Buyer: I’ll offer you $60.

Seller: Well, perhaps I could accept $90.

Buyer: Maybe I can pay $65.

Seller: $85.

Buyer: $75.

Seller: Let’s split it down the middle.

Buyer: Okay, $80 it is.

Reasons to move within the settlement range must pass the credibility “smell test”—that is, in order to be effective, the reason you give for movement within the range can’t smell like garbage to your counterpart. Here are possible reasons you can give TOS for moving within your settlement range. As a seller, you might say, “I am willing to lower my price...

...because of our long-term relationship.”

...as a volume discount.”

...as part of a package deal.”

...because we look forward to your future business.”

...because we have a special sale going on right now.”

...because we are trying to move our inventory”

...if you can pay cash.”

...in order to get your account.”

...to get the process moving.”

...because this is a discontinued model.”

...because I recognize your budget limitations.”

...if you can help us test this product.”

...if you will give us a testimonial.”

Exhibit SR–3 presents a typical negotiating planner for selling a new piece of equipment to a prestigious client who is currently experiencing some business reversals. From a price viewpoint, the negotiation shown in the exhibit is anticipated to be doable, because the estimated settlement ranges are expected to overlap between $75,000 and $80,000 in the “least acceptable” portion of the range.

A key challenge in negotiations is to learn the actual needs versus the positions, or posturing, of TOS. This can be best done by working hard from the beginning of the negotiation, in the orientation and fact-finding stage, to start determining the real needs of TOS.

WHAT IT TAKES TO CLOSE A DEAL

There are both logical and emotional aspects to each stage of the negotiation. With these points in mind, there are three things you must do in order to close a deal successfully: (1) satisfy the logical needs of TOS; (2) satisfy the emotional needs of TOS; and (3) convince TOS that you are at your bottom line.

Satisfy logical needs

The logical, hard-data world is a very potent one, predictable and certain. Most U.S. negotiators tend to focus on logical issues, thinking, “If I can show TOS the force of my logic, then I will prevail in the negotiation by the very force of this reasoning.” It is true that we must convince TOS that 2 + 2=4 in order to conclude the negotiation. For example, TOS may like you personally, but unless the equipment you are selling does what you say it will do, you are unlikely to consummate the negotiation. However, while logic is a key part of the playing field, it is by no means the only part.

Satisfy emotional needs

While we almost always pay attention to the logical needs of TOS, we often neglect the emotional needs. “If 2 + 2 = 4, then what do emotions have to do with it?” you may ask Everything. In fact, emotions are often more important in negotiations than logic. If TOS’s emotional needs aren’t met, this can block TOS’s willingness to deal fully with the facts you have gathered. Think of your own reaction when negotiating with someone you really detest, compared with negotiating with someone you trust and respect. You may say, “It doesn’t really matter, because business is business.” But if you’re like most people, you will behave very differently in these two cases. You can bet that there is a much better chance of successfully concluding a deal in the second situation.

Consumers routinely defy logic in their purchase decisions. For example, in the purchase of luxury cars, the incremental cost of producing a Cadillac is not much more than that of a Buick or an Oldsmobile. So why do consumers love to pay the big bucks for a Cadillac? Because of prestige and status. Not very logical, but certain key needs are being met.

Convince TOS that you are at your bottom line

The final step in successfully closing a deal is to convince TOS that this is as for as you are willing to go. This has a lot to do with the emotional climate and trust that you have developed with TOS. If you have established a positive climate of believability, then you will have a much better chance of convincing TOS that this is as far as you can or will go with your offer.

Which of these three actions are the most important to concluding a negotiation? The answer lies in a remark made by Andrew Carnegie: “Which is the most important leg of a three-legged stool?” They are all important: Each of the three factors is critical in closing a deal.

Remember, though, that it is not always necessary to close a deal and reach agreement with TOS. If you have to exceed your deal breaker in order to conclude the negotiation, you may decide it is better not to make the deal. Ask these questions often: “Is this deal a must?” and “What is the cost of walking out?” Keep in mind that sometimes the best deal is no deal.

In this chapter, we have examined key elements of the negotiating process that can be applied to negotiations: (1) the win-win approach; (2) knowing the stages of negotiation; (3) planning your negotiation; and (4) closing the deal. Though we will explore the differences among cultures throughout the balance of this book, these fundamentals of negotiating apply anywhere in the world. The specific styles and methods of the negotiators involved differ significantly, however, from culture to culture. Let’s begin our intercultural journey in the United States by learning how Americans negotiate.

xhibit SR–1

xhibit SR–1