7

Ebola Epidemic in the Congo 2018–2019: How Does Twitter Permit the Monitoring of Rumors?

7.1. Introduction

Since the year 2000, the research in human and social sciences has been revolutionized by the advent of the digital age. Generally, humanities are undergoing a deep change due to this digital revolution (Quentin and Citton 2015).

From these cultural and social paradigms, a new field emerges, at the crossing of computing, human and social sciences: digital humanities. This field particularly investigates the social and cultural impact of information and communication technologies and plays an active role in the design, implementation, questioning and subversive nature of these technologies today (Rieffel 2014).

Current studies are focused on studying the subversive defaults of these technologies, in particular those of societal culture, humanity and civilizations (Breton 2000).

Few papers analyze positive applications of such technologies for humanities and individuals, particularly to solve social and societal issues. In this context, health is a major social issue which is deeply revolutionized by these technologies. Health studies tend to report potential abuse of digital technology, especially in terms of ethics (Colloc 2014).

However, digital technology has had a positive impact in the field of health, specifically concerning the management of complex sanitary problems, for example, epidemics. But a few papers have analyzed this positive impact, particularly the positive repercussions of social networks in the health domain.

The last major Ebola epidemic in Africa took place in 2014–2015. This epidemic mainly affected three West African countries (Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia). It killed 20,000 people. A number of articles have investigated the rumors that circulated on Twitter during this epidemic. For example, the article by Fung et al. (2016) pointed out that these media disseminated false information about the treatment of the disease, such as bathing in salt water to cure it.

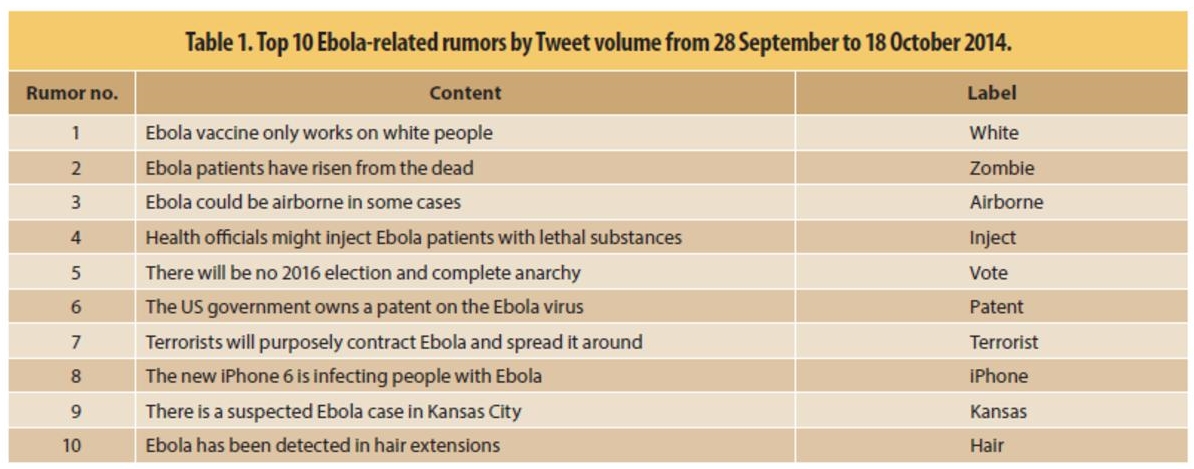

The article by Jin et al. (2014) also pointed out that these media were behind fake news of a snake at the origin of the epidemic. This article was also listed in the top 10 rumors about the Ebola epidemic circulating on Twitter (see Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1 Top 10 rumors circulating on Twitter (Jin et al. 2014)

Ebola Virus Disease is still raging today in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), since August 1, 2018. It has killed more than 2,050 people. It is the second largest epidemic after that of West Africa (Ebola Outbreak Epidemiology Team 2018; Medley et al. 2020).

In addition, numerous studies have shown that Twitter is used by public health organizations, in particular to inform, educate or monitor the state of health of populations, particularly in the event of a disaster (Hart et al. 2017). However, no studies have been conducted to determine who is communicating about the current Ebola epidemic in the DRC and what types of tweets/rumors are being circulated (Tanti et al. 2012).

To answer this question, we conducted an analysis on Twitter via the Radarly® software, over a period from January 4, 2019 to July 7, 2019. The keywords Ebola and #Ebola were used, with a filter on the French language. A total of 17,282 tweets were collected and classified via the software. The tool also extracted and represented the knowledge in a cartographic way (volume of publications/time, etc.). It also made it possible to identify the dominant themes in the form of clusters. The tone of the messages has also been determined.

After a description of the methodology used, this chapter presents the main results obtained, in particular the fact that several actors communicate around the epidemic, in particular the general public, experts, politicians and the press.

7.2. Materials and methods

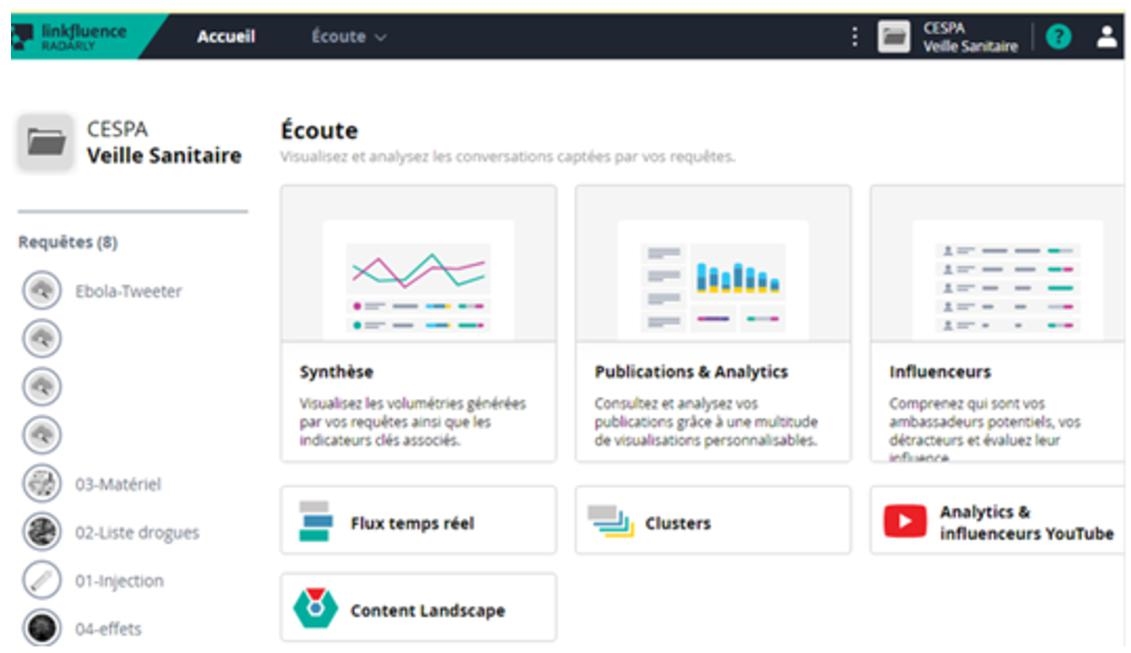

To carry out this study, we used the Radarly® social media monitoring software marketed by Linkfluence (see: https://radarly.linkfluence.com/login) and operating in SAAS mode (see Figure 7.2). This software is accessible online on subscription and allows us to collect data on the social web (Tweet, Facebook, Instagram).

Figure 7.2 Radarly interface.

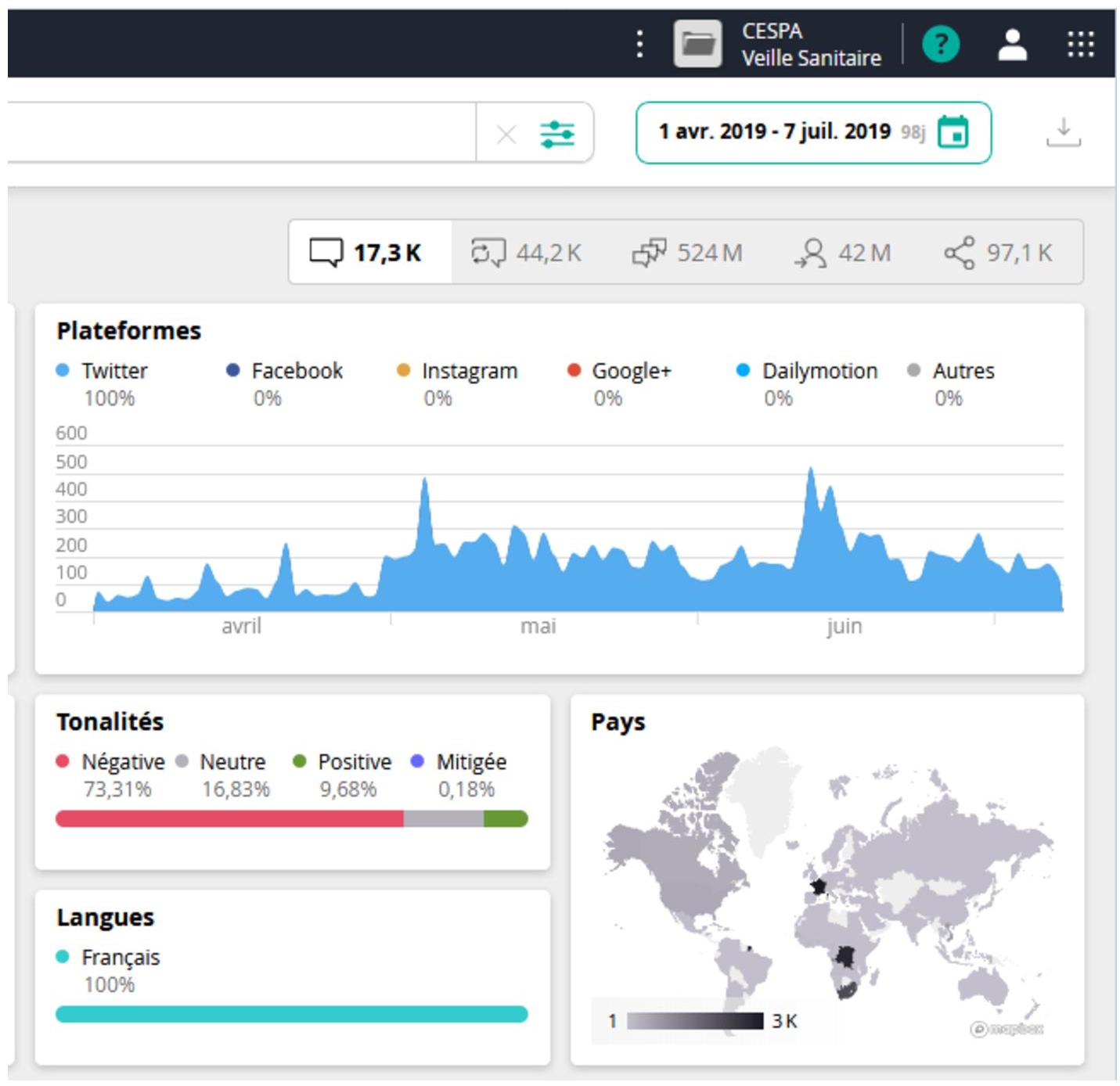

The software also makes it possible to represent the results in a cartographic manner, in particular in the form of clusters of dominant subjects. It also makes it possible to carry out analyses of the tone of the messages published. It identifies “influencers” (people or groups who speak on a given topic or theme). It allows the export of data in .csv format to deduce statistics (see Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3 Graphical representations of Radarly® data.

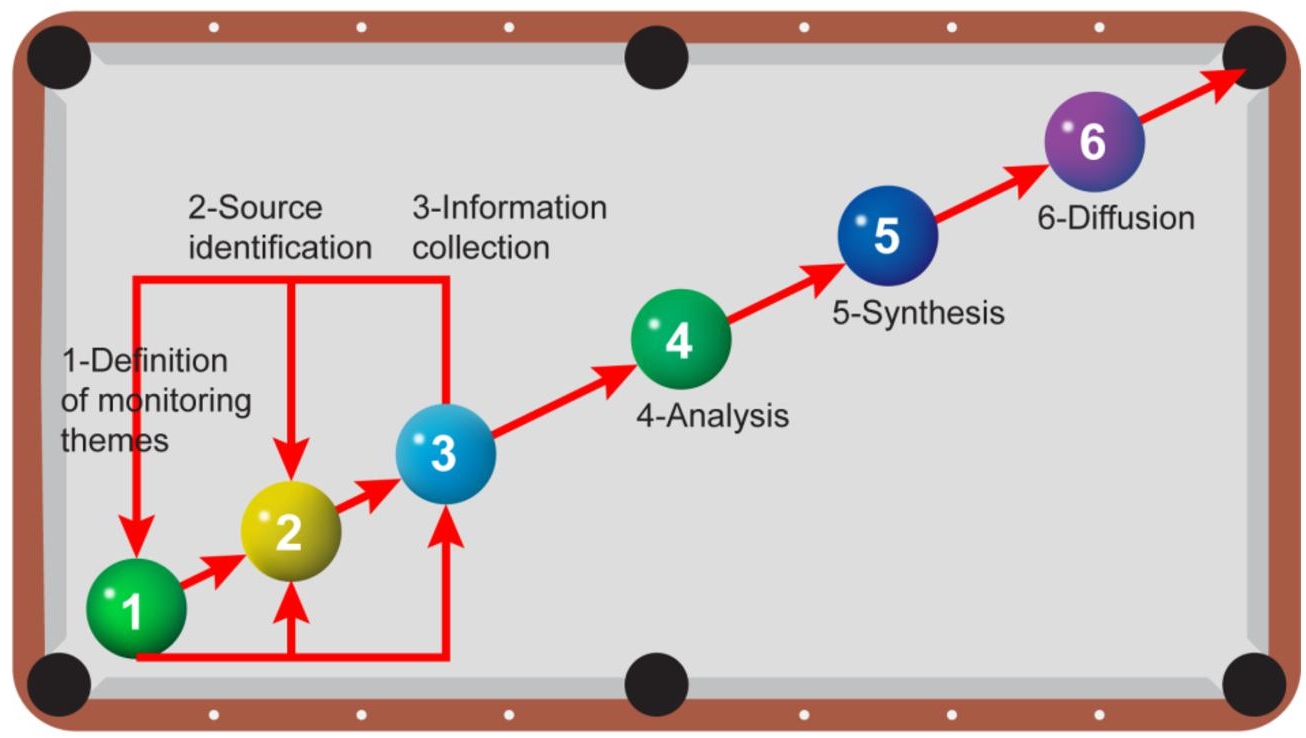

To collect data from Radarly® software, we applied the monitoring process and the methodology (see Figure 7.4) developed by Tanti et al. (2012) in the article entitled “Pandémie grippale 2009 dans les armées : l’expérience du veilleur”, which includes six stages: definition of monitoring themes, identification, collection, analysis, synthesis and distribution of documents.

Figure 7.4 Monitoring process (Tanti et al. 2012).

Concerning the first step, the definition of the themes of monitoring, the keywords Ebola and #Ebola were used in the request, with a filter on the French language.

Concerning the second and third stages, the identification and selection of documentary sources, we only selected the collection of tweets on the social network Twitter via the platform.

The analysis step was done using Radarly® cartographic analysis and representation functionalities.

We analyzed tweets posted on Twitter over a period from April 1, 2019 to July 7, 2019. A total of 17,282 tweets were collected, classified and categorized via the software.

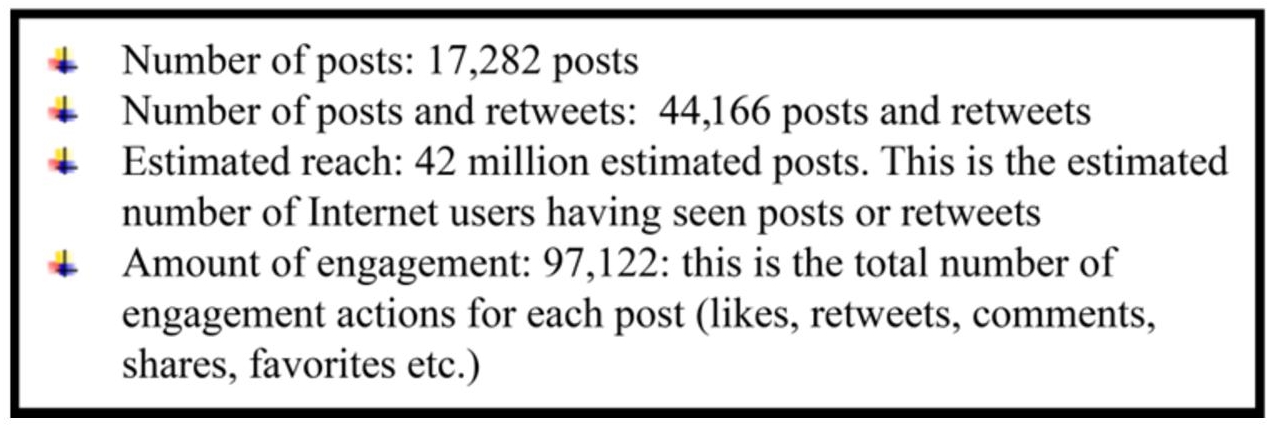

Figure 7.5 summarizes the number of data collected and analyzed.

Figure 7.5 Data collected

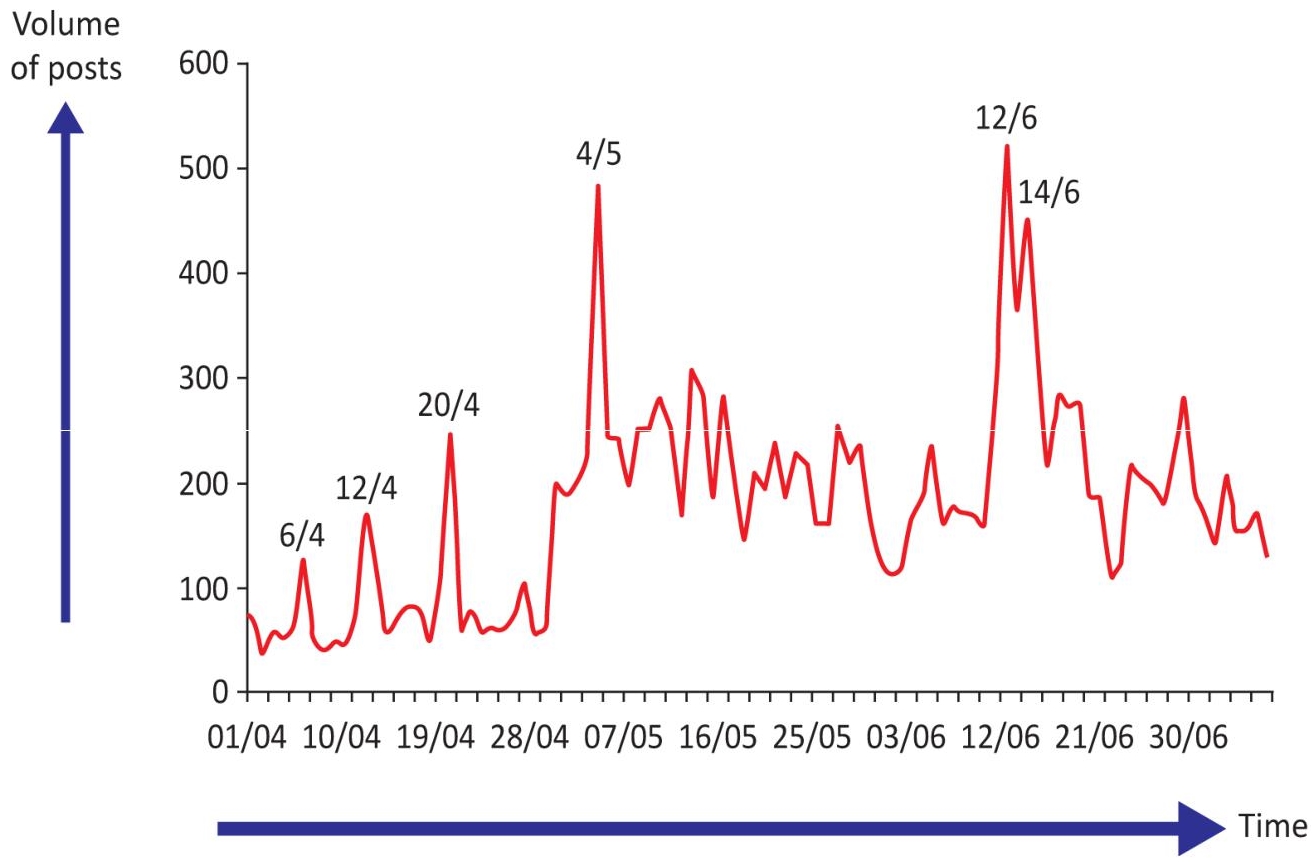

The software also enabled cartographic representations of the volume of publications as a function of time (see Figure 7.6), making it possible to deduce media peaks intimately linked to health events.

Figure 7.6 Cartographic representation of the volume of publications as a function of time (January 4, 2019 to July 7, 2019).

7.3. Results

The requests have identified the actors who communicate on Twitter concerning the Ebola disease, which has been raging since January 8, 2018 in the DRC and has left more than 2,000 people dead.

The filter on the French language made it possible to only select tweets written in French. The analysis also made it possible to identify the messages conveyed.

The main players found were:

– the general public, mainly Congolese citizens and associations;

– experts and health organizations (Ministry of Health of the Congo, WHO, etc.);

– the press, mainly Congolese, etc.;

– politicians, mainly Congolese.

7.3.1. Regarding the general public, the citizens

With the advent of social networks, the forms and possibilities of communication offered to citizens have been considerably multiplied. Citizens and the general public can easily and instantly put their personal opinions online on their own site, on Facebook or other networks. A study even sees Twitter as a “public opinion barometer” (Boyadjian 2014). This advent of the social web has ushered in a new era, the “e-democracy”. This sociological concept, developed in the early 2000s, underpins three impacts on citizen life: rapid access to a mass of information, communication and citizen participation favored by new technologies and more direct deliberative action (Rodota 1999).

In our study, it is mainly Congolese citizens and associations who speak out on the epidemic on the social network. In the Congolese population, there are divided opinions and two populations: a population that “believes” and a population that does not “believe” in the disease.

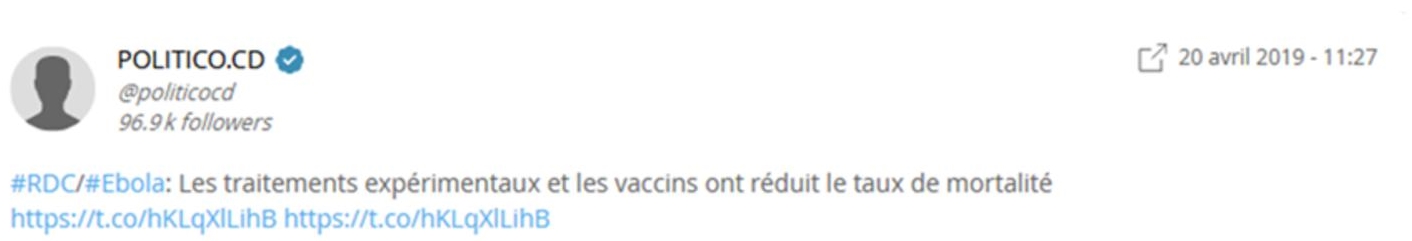

The party that “believes” accepts the disease and the epidemic and considers it as a public health problem. It adheres to medical treatment and preventive measures. It relays messages of scientific information, education and awareness, etc. As an example, we can cite a tweet relaying the effectiveness of the vaccine (see Figure 7.7).

Figure 7.7 Tweet relaying the effectiveness of the vaccine.

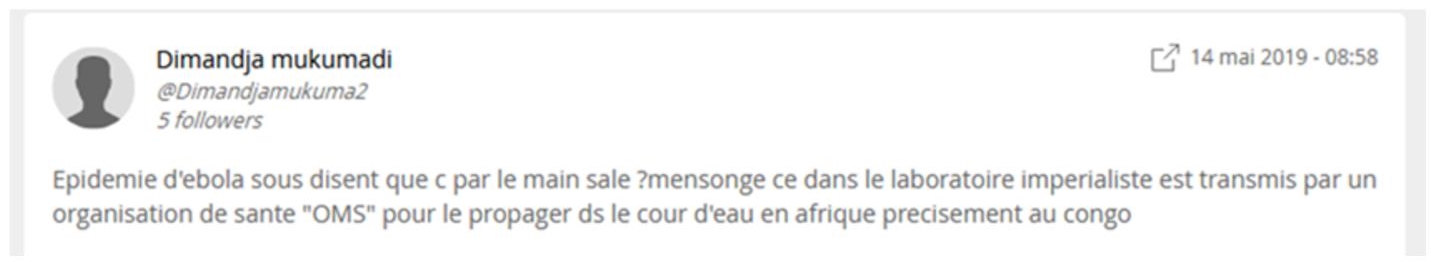

The rest of the population is less “gullible” and denies the disease. It constitutes the majority of the tweets found (high negative tone). Thus, despite the efforts of response teams since the start of the epidemic in August 2018, this population considers the disease as a plot to destabilize the country. This population spreads rumors. They accuse, for example, the laboratories or the WHO of having created the virus (see Figure 7.8).

Figure 7.8 Tweet accusing laboratories of creating the virus and spreading it via water in the Congo

In the same context, Figure 7.9 shows a message spreading a rumor that the disease was sprayed from helicopters.

Figure 7.9 Tweet from a Congolese man spreading a rumor that the disease was sprayed from helicopters.

7.3.2. Regarding the experts

With social networks, “experts” can now exchange among themselves, set up actions, collective reflections and form networks of expertise on these media (Alloing and Moinet 2010).

In this context, health organizations, experts and research organizations have also taken over the social web to communicate, raise awareness and inform populations. Many studies have shown that in this new environment, Twitter is now used by many public health organizations to inform, educate and monitor the health of populations, especially in the event of a disaster (Hart et al. 2017).

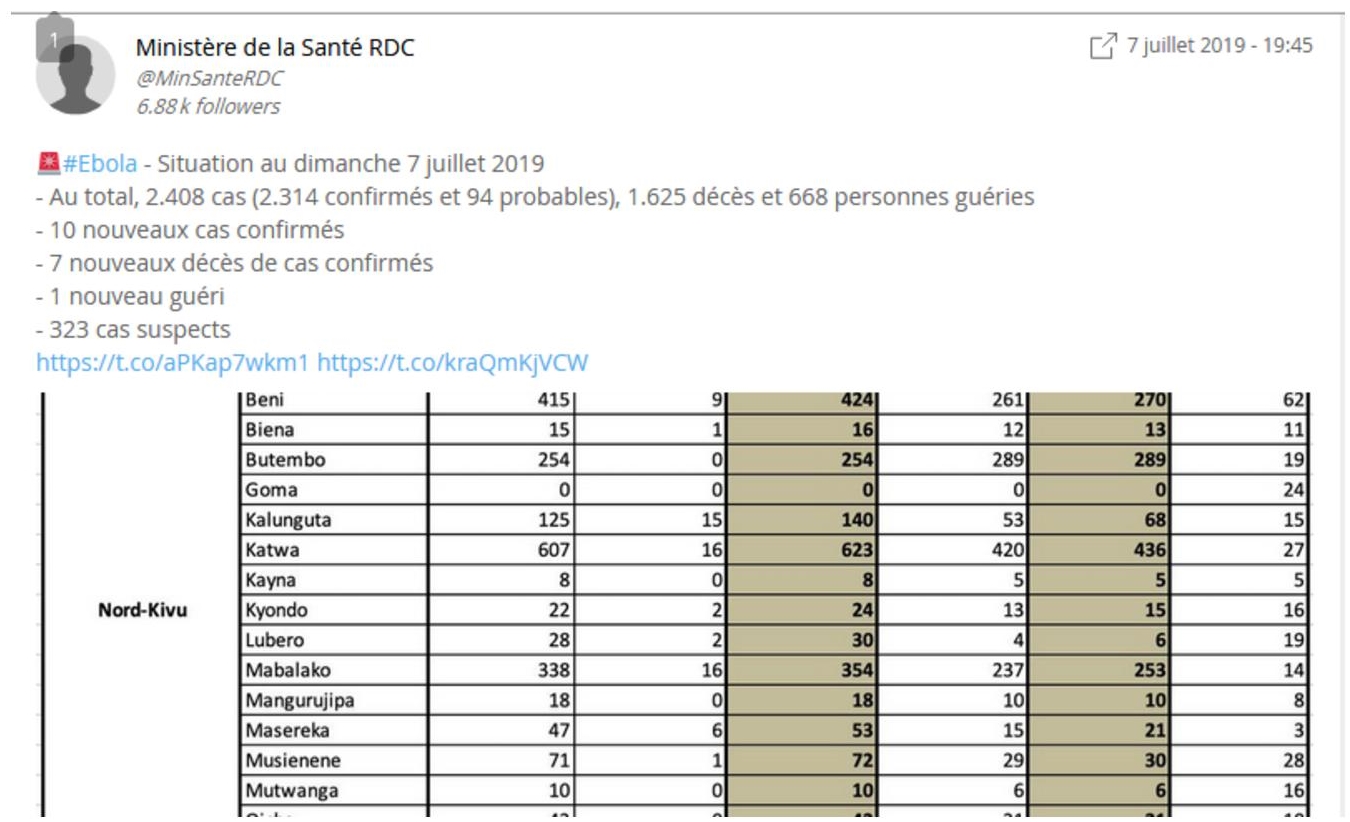

In our study, it was mainly the national and international health organizations responsible for the response to the disease who spoke on Twitter during the study period. In particular, we observed that they shared many tweets to inform the general public. For example, the Ministry of Health of the DRC made a regular update on the disease (see Figure 7.10), which it relayed on Twitter.

Figure 7.10 Tweet relaying a daily update on the disease from the Congolese Ministry of Health.

7.3.3. Regarding the media

Medical topics, including societal health debates, health disasters and global epidemics, have always been topics of interest to the media. Health issues thus undergo a double transformation in the media space: quantitative in their degree of social visibility and qualitative in their politicization (Gerstle and Piar 2016). At a time when the challenges of health and medicine weigh heavily on the choices of society, the press is thus called upon by all those who intervene in this debate, in our study, public and political men, experts, organizations of health, the citizen and more generally society.

Mathien insists on the visibility of health topics in the media. For him

to note that health has become a particularly privileged sector in the fields of observation and investigation of the mainstream media, means that it has left, in many aspects, professional and specialized circles (Mathien 1999, translated).

It is also the observation of Champagne who

observed, during the 1980s and 1990s, a strong development of medical information in the general information media, in the medical press and in the specialized press (Champagne 1999, translated).

The theme of health presents two types of space: a public societal space and a specialized space, and therefore offers the opportunity to study their confrontation (Zappala 1997). The first is largely driven by the media and the general press; the second is driven by specialized media specific to the scientific community (Zappala 1997). In this context, the advent of Web 2.0 has made it possible to open up these borders.

In the context of our study, the media are the vehicle for informing the debate in the democratized digital public space. They are also the vector of communication between the actors of the public debate. They are also involved. They can give their opinions and are likely to guide or even catalyze discussions. In any event, they are part of the debate.

In our work, it is mainly journalists and the press, both Congolese and international, who speak out. They tend to share WHO response releases, and prevention and awareness messages (see Figure 7.11).

Figure 7.11 Tweet from the media relaying a preventive message to mobilize to fight the Ebola epidemic.

7.3.4. Regarding the politicians

Public figures and political parties have been communicating via the Internet for over a decade. The way they have used this tool and the uses they make of it have already given rise to a certain number of works (Greffet 2001; Sauger 2002; Villalba 2003).

Their communication on the Web is done in particular via social networks such as Twitter, websites or blogs of political parties, as well as via personal websites or blogs, which may or may not be hosted by the party concerned (Longhi 2013).

They also use more conventional media such as the local, regional or national daily press, or react via blog posts associated with these online media (Gerstle and Piar 2016).

They are also communicated via institutional, administrative and legislative documents (parliamentary, administrative reports, etc.). According to Poupard, it is “an activity located at the crossroads of editorial, technical and socio-organizational issues” (Poupard 2005, translated).

Social networks have also enabled public and political figures to find a considerable strike force which has extended their area of influence (Maarek 2007), in particular to increase the opportunities to reach the population (Barboni and Treille 2010).

In our work, it is mainly Congolese politicians who speak out. They relay in particular prevention, health education or awareness messages. For example, Figure 7.6 shows a tweet relaying the photo of the President of the Congolese Republic (H.E.M. Felix Tshisekedi), who complies with medical requirements during his national tours (see Figure 7.12).

In conclusion, our study thus found 12 main influencers and highlighted a negative message tone of 73.31%.

Figure 7.12 Screenshot of a tweet showing the president of the DRC applying hygienic gestures during his national tour.

7.4. Conclusion

The Internet is seen as a considerable source of health information. Social networks were a source of health information with particularly high added value. Social networks make it possible to follow epidemics, especially the rumors and the actors communicating around these rumors (Tanti and Alate 2020).

The 2014–2015 Ebola epidemic was an interesting source of analysis of these rumors that have been the subject of a number of publications (Jin et al. 2014; Fung et al. 2016).

Our work focused on the 2018–2019 epidemic, and shows a certain number of interesting results. For example, unlike the results obtained during the 2014–2015 epidemic, our study highlights a shared Congolese population. Some people accept the disease and adhere to the treatment, and another party views it as a conspiracy (Tanti and Alate 2020).

Our study suffers from several limits. The short analysis period, like the choice to limit the study to the French language, is questionable. In addition, in our analysis, we did not take into account other media, such as Facebook and forums. Finally, it is especially the choice of analysis on the social network Twitter itself which is questionable. Indeed, this media limits the number of characters present in messages. It thus limits long discussions, therefore making it the relay of current events and the engine of polemics and debates, rather than the federator of true micro-communities.

In general, as a recommendation to change the mind of the defiant population, it would seem interesting to involve the relays of traditional healers and religious leaders who are the first to be consulted by this population in the communication campaign on social networks.

7.5. Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Dr Alate Kodzo who participated in this project.

7.6. References

- Alloing, C. and Moinet, N. (2010). Des réseaux d’experts à l’expertise 2.0. Le web 2.0 modifie-t-il la création et la mise en place de réseaux d’experts ? Les Cahiers du numérique, 1(6), 35–53.

- Barboni, T. and Treille, É. (2010). L’engagement 2.0. Les nouveaux liens militants au sein de l’e-parti socialiste. Revue française de science politique, 60(6), 1137–1157.

- Boyadjian, J. (2014). Twitter, un nouveau “baromètre de l’opinion publique” ? Participations, 8, 55–74 [Online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3917/parti.008.0055.

- Breton, P. (2000). Le culte de l’Internet : une menace pour le lien social ? La Découverte, Paris.

- Champagne, P. (1999). Les transformations du journalisme scientifique et médical. In Médias, santé, politique, Mathien, M. (ed.). L’Harmattan Communication, Paris.

- Colloc, J. (2014). Aspects éthiques et impact social du Big Data en santé. Journées Big Data Mininf & Visualisation, Journées EG C et AFIHM.

- Ebola Outbreak Epidemiology Team (2018). Outbreak of Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, April–May, 2018: An epidemiological study. Lancet, 392(10143), 213–221.

- Fung, I.C.-H., Fu, K.-W., Chan, C.-H., Chan, B.S.B., Cheung, C.-N., Abraham, T., Tse, Z.T.H. (2016). Social media’s initial reaction to information and misinformation on Ebola, August 2014: Facts and rumors. Public Health Reports, 131(3), 461–473 [Online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491613100312.

- Gerstle, J. and Piar, C. (2016). La communication politique, 3rd edition. Armand Colin, Paris.

- Greffet, F. (2001). Les partis politiques français sur le web. In Les partis politiques : quelles perspectives ? Andolfatto, N., Dominique, G., Fabienne, O.L. (eds). L’Harmattan, Paris.

- Hart, M., (2017). Twitter and public health (Part 2): Qualitative analysis of how individual health professionals outside organizations use microblogging to promote and disseminate health-related information. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 3, e54 [Online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.6796.

- Jin, F., Wang, W., Zhao, L., Dougherty, E., Cao, Y., Lu, C.-T., Ramakrishnan, N. (2014). Misinformation propagation in the age of Twitter. Computer, 47(12), 90–94.

- Longhi, J. (2013). Essai de caractérisation du tweet politique. L’information grammaticale, 136, 25–32.

- Maarek, P. (2007). Communication politique et marketing de l’homme politique. Lexis Nexis, Paris.

- Mathien, M. (1999). La santé dans la quête du bonheur dans la cité. In Médias, santé, politique, Mathien, M. (ed.). L’Harmattan Communication, Paris.

- Medley, A.M. (2020). Case definitions used during the first 6 months of the 10th Ebola virus disease outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo – Four neighboring countries, August 2018–February 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(1), 14–19.

- Poupard, J. (2005). Écrits d’écran : du mélange des genres. Communications et langages, 144, 65–76.

- Quentin, J. and Citton, Y. (2015). Manifeste pour des humanités numériques 2.0. Multitudes, 2(59), 181–195.

- Rieffel, R. (2014). Evolution numérique, révolution culturelle ? Gallimard, Paris.

- Rodota, S. (1999). La démocratie électronique. De nouveaux concepts et expériences politiques. Apogée, Rennes.

- Sauger, N. (2002). Les partis sur le Net : première approche des pratiques virtuelles des partis politiques français. In L’Internet en politique, des États-Unis à l’Europe, Serfaty, V. (ed.). Presses Universitaires de Strasbourg.

- Tanti, M. (2012). Pandémie grippale 2009 dans les armées : l’expérience du veilleur. Médecine & Armées, 40(5), 389–401.

- Tanti, M. and Alate, K. (2020). Quelle utilité des réseaux sociaux pour l’analyse des épidémies ? L’exemple de Tweeter pour le suivi de l’épidémie d’Ebola 2018–2019 en Afrique. OCTA International Multi-Conference on Organization of Knowledge and Advanced Technologies, Tunisia, 6–8 February.

- Villalba, B. (2003). Moving towards an evolution in political mediation? French political parties and the new ICTs. In Political Parties and the Internet, Net Again? Gibson, R., Nixon, P., Ward, S. (eds). Routledge, London.

- Zappala, A. (1997). La médecine médiatisée : entre la médicalisation du social et la socialisation de la science. Hermès, 21, 181–190.

Note

- Chapter written by Marc TANTI.