Chapter Three

MACKUBIN, GOODRICH & CO., 1925–1927

Rowe joined Mackubin, Goodrich & Co. in 1925. A relatively small financial firm in Baltimore, it was quite different from Jenkins, Whedbee & Poe. He would spend his next twelve years there and form his basic investment beliefs.

George Mackubin started the firm as George Mackubin & Co. in January 1899, after he borrowed $300 to buy a seat on the Baltimore Stock Exchange. G. Clem Goodrich, sixteen years older, joined as its second partner eleven months after the firm opened its doors. John C. Legg, whose name the firm still carries today, was hired a year later as the “board boy.” His job was to keep the prices for the stocks being traded up to date on the large blackboard at the front of the public trading room. Five years after he was hired, John Legg was made a partner, the rapid rise an indication of his ability and the respect that he earned from others.

Mackubin's father was a wealthy lawyer and his mother a direct descendent of Martha Washington. An outgoing man, Mackubin ran the firm in an aggressive way, but was fair and respected by his employees. He believed in focusing on a few industries and companies and researching them very carefully. The oil and gas business around Houston, for example, caught his fancy. To find out what was really going on there, he would camp out for weeks in the hot, humid, mosquito‐ridden oil fields near the Gulf of Mexico. He thus got his information directly from the drillers and the oil exploration teams in the field rather than from the front office. Soon after he was hired, Rowe reportedly found himself on a trip down to the oil fields with Mackubin and his son. Mackubin would be a founder of the Houston Natural Gas Corporation in 1928 and ultimately made millions of dollars for the firm's clients due to the appreciation of the company's stock. He also made money for the firm from the commissions on the capital raised in its many bond and stock offerings. As Houston Oil, the company was sold to the Atlantic Refining Company for $198 million in 1956 ($1.76 billion in 2018 dollars).

This kind of thorough, hands‐on research before investing, investing in rapidly growing industries, holding the equities over a long period of time, and focusing on a few outstanding companies were key lessons for Rowe. It was a unique approach for the time, and later became part of the basis for his Growth Stock Philosophy.

Clem Goodrich's background was quite different from Mackubin's. His father had been a Presbyterian minister in Hagerstown, Maryland. Perhaps because of this upbringing, he was more taciturn and even‐tempered. He had a reputation in Baltimore as a man who could be trusted. Before he joined Mackubin to form Mackubin, Goodrich & Co., he had been the manager of the Baltimore Clearing House, a company that moved checks and securities between banks.

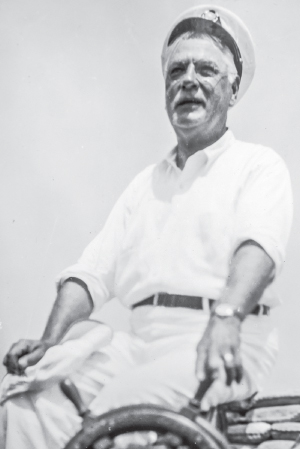

The third partner, John Legg, always addressed as “Mr. Legg” except for a few close friends, was tall, athletic, and known to be aloof, opinionated, and tough. He had none of the money or social connections of George Mackubin. His education stopped at high school. His father was the police commissioner of Baltimore. He could be difficult to get along with, but he was, by the sheer force of his personality, the dominant presence at the firm. In the mid‐1920s, when Rowe joined, he was in charge of day‐to‐day operations. He was the man who “made things happen,” in the words of his grandson, Bill Legg, and effectively was the managing partner, even though this was not his official title at the time.

Mr. John C. Legg, mentor to Mr. Price and then managing partner of Mackubin, Goodrich. Photo owned by Mr. William Legg and family.

Joseph Ward Sener, Jr., who later became managing partner and vice‐chair of the board, remembers running into Mr. Legg on the street shortly after he was hired.

“Where's your hat?” demanded Mr. Legg.

“I beg your pardon?” Sener replied.

“You don't have a hat on. Let me tell you, a gentleman would just as soon be seen on the street without his trousers as he would without a hat.” Sener purchased a fine fedora that same day, even though it cost a week's wages.”

The different personalities and interests of these three men were probably what gave the firm the strength and ability to survive and prosper in the tumultuous years prior to 1922. A fire had totally destroyed Baltimore's financial district in 1904. The stock market went into free fall and closed its doors at the onset of World War I on July 31, 1914, and did not reopen for four months. The sharp recession of 1921 created its own financial challenges.

One example of the firm's expertise was Goodrich's skill at shorting. Despite his conservative background, Goodrich had a feel for the market and greatly enjoyed short‐term trading. He might sell $5,000 of a stock short ($73,380 in 2018 dollars) in the morning and close out his position in the afternoon, making perhaps $500 ($7,338 in 2018 dollars) on borrowed money on a good day.

Shorting is a stock trading strategy used when the trader believes a stock will decline in value. To execute a “short,” the trader tells his stockbroker to short 100 shares of a stock that he believes will go down. He never actually owns these 100 shares. His broker borrows them from a third party and then immediately sells the 100 shares for $10 per share. The broker credits the $1,000 from the sale to the trader's account. At that moment everyone is even. The trader has borrowed 100 shares. The broker quickly sold these shares for $1,000, which is in the trader's account. The trader owes the third party the shares, but he has the $1,000 in his account to buy them back at the market.

If the stock goes down to $5 per share, the trader might decide to “close out” his trade. He calls his broker, who buys the 100 shares that he owes to the third party for $500 at the market. His broker then returns the 100 shares that he borrowed to the third party. After deducting the $500 required to buy the shares in the market, at $5 per share from the $1000 in his account, the trader has a very nice profit of $500. Too bad he didn't buy more.

The problem about shorting comes if the stock goes up instead of down. The upside is infinite. A trader can end up losing far more than the money he thought he was dealing with when he entered the transaction. In the same example, suppose the stock tripled to $30 per share. The trader decides that enough is enough and tells his broker to close out the trade. The broker buys the 100 shares of stock in the market for $3,000. He sends the 100 shares back to the third party that he borrowed them from. The third party has been getting any dividends that might have been paid in the interim and his stock has gone up 300 percent. He is quite happy. The trader, on the other hand, had to pay $3,000 to buy back the stock and he only had $1,000 in his account. After paying his broker the difference and a commission on both buying and selling, the trader realizes that he has lost more than $2,000 due to the stock's increase, or twice the amount he used to buy the original 100 shares.

In such short trading, the smart speculator was careful to place limit orders so the trade is closed out if the loss becomes excessive. One of Goodrich's favorite companies to trade was General Motors, a company well known to Rowe because of its relationship to DuPont. Its volatility in the 1920s made it attractive because of the opportunity to profit from the big swings in price.

It must have been exciting for the twenty‐seven‐year‐old to sit next to Goodrich in his small office at the Baltimore Stock Exchange and watch as he traded short‐term fluctuations in the market. He undoubtedly used charts and the so‐called “technical” tools which helped the savvy trader to guess which way a stock was going and by how much. All publicly traded stocks are charted today by a number of services, and the same technical formations below, and many more, are still monitored by the traders.

Usually, charts are produced by plotting the price of the stock on the vertical axis, and time on the horizontal axis, with daily trading volume in shares shown in these charts on the lowest horizontal axis. Such charts create patterns that have meaning for the skilled trader. For example, a trader might note that a stock abruptly moved up on significant volume. During this upward move, “gaps” were created when a stock rose several points without a trade. Such gaps are almost always “filled,” even if it takes years to do so. That is the rising stock will often eventually retreat back to the price of the stock at the bottom of the gap. The difficulty is figuring out how long this might take

Stock chart of “gaps.” TSR Trading Setups Review.

Another common formation is a “head and shoulders.” A stock might rise in price, then stay at a constant price for a number of days, then rise again, stay for one or two days, and then collapse back to near the price of the stock before it began the second up move to form the “head” of the formation (see chart.). If the stock should fall back through its “neckline” – the line that goes from one shoulder to the next – through the “head,” the stock will often fall by the difference in stock price between the top of the “head” and the “shoulder.” For Goodrich as a stock trader, such a formation would have been a classic example of a shorting opportunity.

Stock chart of “head and shoulders.” TSR Trading Setups Review.

A final example of a stock formation, which is often noted in publications such as the Wall Street Journal, is a “resistance” level (see chart). These are prices where a stock has traded for a long period of time at good volumes. Usually such resistance levels have been tested several times, as the stock falls back to this level, only to recover. A stock can move up from such a resistance level for many years. With bad news, it could come back to it. A trader might bet that the resistance will hold and place a buy order at this resistance level.

Stock chart of “support and resistance levels.” TSR Trading Setups Review.

Such techniques are controversial and risky. Watching Goodrich make mistakes, as all traders do, would have confirmed Rowe's belief in buying and holding. Few individuals have been able to make money consistently by short‐term trading. Most of those who seem to be able to do it successfully for a short time are almost always wiped out over the long term. In later years, however, Rowe was rarely without a chart book, just for “a final check,” before buying or selling.

Later, Rowe described this approach succinctly, as reported in The History of T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc: “The majority of people think of common stocks as something to buy or sell for speculative profits. They believe it is necessary to guess the ups and downs of the stock market to be successful. We do not think it is a good approach. The greatest American fortunes were the result of investing in a growing business and staying with it through thick and thin.”

The market does seem to have a life of its own, which can be mesmerizing to watch. Trading can slow down to a crawl as traders feel its pulse. Then there will be a sudden increase in activity – often based just on a rumor – and it will swing up or down with heavy volume. It's almost like watching a large school of fish that, for seemingly no reason at all, will turn on a dime and swim in perfect unison with flashing fins in an entirely different direction.

In 1925, when Rowe first walked between the impressive white marble columns and opened the large, dark mahogany doors of Mackubin, Goodrich & Co. at 111 East Redwood Street, the bull market of the twenties was well on its way upward. The Dow Jones Industrial Average had more than doubled to 135 from its low in 1921 just four years before; Mackubin, Goodrich & Co. was rapidly expanding from its base of 30‐plus employees. Although its emphasis was on building up its stock brokerage business, the firm was hiring employees for its bond business as well.

Bond offices of Mackubin, Goodrich, circa 1925. Legg, Mason corporate archives. All rights reserved. Copyright @ Legg, Mason

The firm was then best known for its expertise in fixed‐income securities. When the stock market was closed for four months in 1914, in order to keep the young firm going, the partners made their first foray into real estate by financing and selling mortgages for the Roland Park Company, which had just begun to develop neighborhoods in Baltimore's northern suburbs. By the beginning of 1925, the overall mortgage market, interest‐bearing mortgage notes, and mortgage bonds had become an important part of their business.

Rowe was likely hired by the firm because of his successful experience at Jenkins, Whedbee & Poe as a fixed income salesman. It is quite possible that Mr. Legg himself was involved in hiring Rowe, as he soon became his mentor.

As the firm prospered in the long bull market, Rowe's compensation would have risen with his increasing experience and capability as a bond analyst and salesman.

Eleanor Price, born 1904; Goucher senior yearbook, 1926. TRP archives.

About this time, he met a pretty, dark‐haired Goucher College student named Eleanor Baily Gherky. She was six years younger than Rowe, but that didn't seem to matter a bit. The winter of her senior year, on December 18, 1925, he gave her an engagement ring, and they were officially engaged on December 26. They were married September 18, 1926, at her family's summer home in Ocean City, New Jersey.

Mr. Rowe Price, circa 1926. TRP archives.

When the couple returned from their delayed honeymoon to Europe in August 1927, they rented a small house at 11 Talbot Road in Baltimore. The city life would have appealed more to Eleanor than did Glyndon, where Rowe had lived as a bachelor prior to their marriage. There was more to do in Baltimore and she had a number of friends and classmates from Goucher who lived nearby. For Rowe, the Baltimore house was not far from his office and near where many of his clients lived. It might have been difficult for him, however, to leave the Glyndon area and his close‐knit family, which had been such a focal point of his life up to then.

Eleanor's family lived in what was known as the West Diamond Street Townhouse Historic District of Philadelphia. The area indeed featured many beautiful Victorian townhouses and catered to a new class of entrepreneurs growing rich on the important inventions of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Her father, William D. Gherky (sometimes spelled Gharky), was born and raised in Portsmouth, Ohio. In high school he became interested in telegraphy, which was just being introduced. This technology allowed an operator skilled in Morse code to send messages instantly over long distances to others, using wires. At the age of eighteen, in 1886, Gherky left high school to become a telegraph operator for the railroads. Two years later, he was employed by the Edison Electric Company in New Jersey to build a brand‐new pilot plant to mass‐produce electric light bulbs.

Mr. Gherky, Eleanor Price's father, born 1868. TRP archives.

Edison Electric was where many of the major inventions that would so affect the twentieth century were being developed. Edison's seminal patent for the first long‐lasting electric light bulb that could be economically manufactured would be resolved, after years of legal haggling, in 1898, the year after Gherky arrived at the company. The plant that Gherky was hired to set up was an experimental facility that took the raw concepts developed by the engineers and transformed them into practical manufacturing processes and machinery for the large factory that would mass‐produce the first Edison light bulbs. It was up to Gherky and his crew to iron out the manufacturing and engineering problems on a small scale before the large factory was built that would bring electrical illumination to the world.

This plant was located in Menlo Park, New Jersey in the huge Edison Electric complex. Coincidently, it was near Menlo Park, California, where many of the inventions of the twentieth and early twenty‐first century were first dreamed of and produced in the plants of Hewlett Packard, Apple, Facebook, and the like. The Edison Electric facility was populated by men such as William K.L. Dickson, who developed one of the first motion picture cameras; Reginald Fessenden, who developed a new way to insulate electric wires, without which electricity could not be brought inside; and – the most famous of them all – Nikola Tesla, who today has an electric car named after him. Tesla was a consummate inventor, involved in many fields of technology. Later, at Westinghouse Electric Corporation, working directly for George Westinghouse, Tesla developed the technology of alternating current, which is necessary to transmit electricity over long distances – a technology that Gherky would put to good use later in his own facility.

It was as if all the entrepreneurs in today's Silicon Valley were crowded together on a single large campus in New Jersey – a heady environment for a young, technically inclined man from Ohio.

There are interesting parallels between Thomas Edison and William Gherky. Edison was also from Ohio and was interested in technology, particularly the telegraph, at a very early age. Did Edison, who was thirty‐nine in 1888, and the twenty‐year‐old Gherky actually meet? Did Edison relate to him and personally hire him? We aren't sure of the answer, although Gherky's obituary in the New York Times states that he was “a former research assistant to Thomas A. Edison.” It was certainly an impressive promotion for the young Gherky to suddenly rise from the job of telegraph operator to running one of the most important projects at the Edison Company.

Gherky did not stay at the Menlo Park labs long. Perhaps his inexperience caught up with him. By the end of the year, he was transferred to the engineering department of the Edison United Manufacturing Company. After another year, he left for the Field Engineering Company in New York in 1890 and began what became his life's work: designing and building electrical transportation systems and the associated electrical distribution equipment. Gherky constructed subway and cable systems for this company in the cities of Detroit and Buffalo. One of his most famous projects, in terms of publicity, at least, was designing the lighting for the first Broadway play to use electrical lighting, Little Lord Fauntleroy.

In 1892, Gherky moved to Philadelphia, where he installed the city's trolley line and the associated electrical systems. He went out on his own in 1911 and organized the Railway Track‐Work Company, which made electrical railroad equipment, and formed the General Grinding Wheel Corporation. Throughout his career, Gherky not only designed systems, but was also an inventor, holding important patents for manufacturing processes, electrical equipment, and telephonic equipment.

These activities made Gherky a wealthy man. When he died on January 17, 1937, his estate was worth $389,710 (about $6.65 million in 2018 dollars). Like Samuel Black, Rowe's grandfather, he was an entrepreneur. He and Rowe were certainly close, as Gherky entrusted his son‐in‐law to manage his assets.

Eleanor, by all reports from those who knew her best, was devoted to Rowe and shared his passion for travel and, at the same time, understood his long working hours. She organized Rowe's personal life in an efficient behind‐the‐scenes manner, as she had been brought up to do as a woman of her time and social position. Her dinner parties were carefully planned, with everyone having a place card, even if Rowe was just having supper with his junior associates. The food was always excellent and beautifully served, the silver freshly polished and glittering, and the cook and butler working effectively together. She would allow Rowe to dominate the conversation while she remained in the background, thoughtful and considerate to those around her, as I can attest as a guest at several of these dinners.

They both kept daily diaries, but hers reflected the social side of their life. It mainly contained the names of friends, the specific parties they went to, what was served, and the specific rooms they had stayed in at various clubs and hotels where they might return. She was a generous supporter of Goucher College, served as chairwoman of the board, and often ran local fundraising campaigns for the school. As Ann D. Hopkins, who worked with Eleanor on several such projects, reported, she was a good organizer and always got the job done effectively and efficiently. If someone was lagging a bit, she would often pick them up in her car, without any fuss or embarrassment, and help them keep the fundraising appointments that they had accepted but were slow in delivering. Hopkins found that Eleanor was always very cordial and natural to be with.

Eleanor was quite interested in gardening, although more from a supervisory perspective. She let Rowe get his hands dirty digging around the roses that became one of his most important hobbies. She was president of the local garden club and also active at the state and national level. Her keen, active interest in projects outside the home must have reminded Rowe of his own mother. Thus, by the standards of that time, she was an ideal partner for a man whose major focus was business. An independent woman, she managed their social life in addition to her community involvements, to allow her husband more time to build the business.

Their major disappointment was that there were no children. She finally took matters into her own hands, although Rowe certainly did not object, and went to an adoption agency in New York City. On June 28, 1937, they adopted their first child, Richard (Dick) Baily Price. Two years later, they returned to adopt Thomas Rowe III.

Growing up in the Price household was sometimes difficult for the two boys, according to Tom and a good friend of Dick's. Like many successful men, particularly of that time, Rowe was a distant father. The boys complained that when they took a vacation, Rowe would take briefcases full of business reading material in which he buried himself for much of the day. He was a tough disciplinarian, but fair. The same friend of Dick's tells a story about weeding their large yard. Rowe enlisted his sons for the job and told them that he would pay them fifty cents an hour, a good wage for children in the 1950s. Something came up, and both boys forgot about the job. A week later, in an attempt to teach them a lesson about honoring their commitments, Rowe gathered them into his study and said that because they had not done the work that he had requested, he had to do the job himself. They owed him eight dollars. He collected this sum over time by deducting it from their allowance. Yet despite these issues, both sons loved and respected their father. Young Tom would name his son after his father.

Eleanor was devoted to her sons. She would often pad their allowance to pay for toys and other items that they desperately wanted. She gave the love and affection that business too often kept Rowe from providing. As Tom said, his father “did not try to push us into business. He would have liked it, but he wanted us to do what interested us, and he could see [we] really didn't have the interest.” In the year before he died, according to Tom, his father finally opened up to him. “We had more love and warmth,” he said, “than all the times we had had together. That's because he let his defenses down. He was able to be a real human being.”