Chapter One

THE HOUSE ON DOVER ROAD, 1898–1919

A soft orange glow from oil lamps could be seen through the first‐floor windows of the house at 4801 Dover Road in the small town of Glyndon, Maryland. The flickering light illuminated the branches of the trees dancing to the force of the cold northeast wind. At this early hour, the lamps provided the only light on the street. It had been raining the day before and puddles remained on the hard dirt surface of the street, bordered by wooden sidewalks.

A rooster prematurely announced the dawn as the soft whinny of a horse came from the stable behind the house. Suddenly the sound of a slap on a wet baby's bottom emanated from the interior of the home. It was March 16, 1898, and Thomas Rowe Price, Jr. let out his first cry as his father, Dr. Thomas Rowe Price – the only doctor in town – brought him into the world. He was swaddled in a warm blanket and placed in the arms of his mother, Ella Stewart Black Price, who settled back for a well‐earned rest.

The above account is as imagined by the author after visiting the original house in which Mr. Price was born and following discussions with several local residents, one of whom was delivered by Mr. Price's father and another of whom is an active member of the historical society.

Mr. Price's mother, Ella Price, born 1869. TRP archives; photo owned by Mrs. Margaret Moore, wife of Dr. Moore, Mr. Rowe Price's nephew.

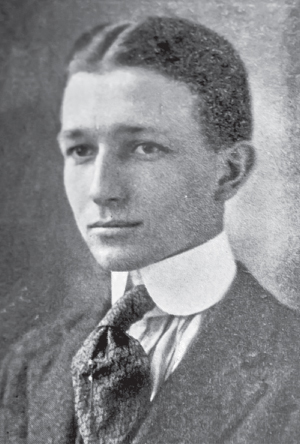

Mr. Price's father, Dr. Thomas Price, born 1865. TRP archives; photo owned by Mrs. Margaret Moore.

Every summer Rowe's future paternal grandfather, Dr. Benjamin F. Price – also a physician – and grandmother, Mary A. Harshberger Price, enjoyed the beach at Ocean City, Maryland. That is where Thomas Price met Ella Black following his graduation from medical school. It was love at first sight for both of them. They were married in 1893 and moved into a new house on Dover Road, a wedding gift from Ella's new husband.

Dr. Price's original home, where he delivered all of his children; built 1893; photographed in the nineteenth century. TRP archives; photo owned by Mrs. Margaret Moore.

It was a large house for the time, with three floors and a square tower on the side, in keeping with the Victorian style of architecture. On the first floor were a large dining room, a living room, and a kitchen in the back overseen by the cook. A handsome staircase led up two flights of stairs to the bedrooms and a large sleeping porch for hot summer nights. Also on the first floor were Dr. Price's office and a small laboratory off the office where he concocted his medicines. Friends who came to call would enter through the front door and chat with him in his office. Patients would enter and leave through a back door if they needed a physical examination or treatment in his examining room. In those situations, one did not want to advertise serious illness, as the odds of recovery were much lower than today.

Medicine bottles used by Dr. Price. Author's photo.

In the spacious backyard, shaded by tall oak trees, were a carriage house, a barn, and a stable where Dr. Price had two horses, buggies, harnesses, and a cow for milk. In lieu of indoor plumbing, the family used a generously sized outhouse with different‐sized cutouts for different ages. The large front porch was close to the sidewalk and had a comfortable swing. On warm nights the Prices, as well as their neighbors, would sit on the porch and gossip with those who were strolling down the sidewalk. Often singing could be heard from the other houses nearby, with a piano as an accompaniment.

There was plenty of space for Rowe, his older sister, Mildred, and his younger sister, Gahring, who would arrive five years later, as well as his maternal grandfather, Samuel Black, and his grandmother, Margaret Catherine Grubb Black. These grandparents lived with Dr. Price and his family from the time Rowe was two until their deaths in 1910.

Samuel Black had a significant influence on the young, impressionable Rowe. He was a successful entrepreneur involved in real estate – the major investment opportunity for most people at the turn of the century – as well as home construction throughout Baltimore County. His assets in the 1870 census were listed as $70,000 ($1.7 million in 2018 dollars). Today, one is conservative in listing assets for the census taker and this was also likely true at that time. Moreover, Black continued to be an active real estate developer for many more years and didn't retire completely until he moved in with his son‐in‐law. In the 1930s, when Rowe was first describing his Growth Stock Philosophy, he would say, “to find a fertile field to invest in you didn't have to go to college, you only needed what my grandmother called horse sense.”

Mr. Samuel Black, Mr. Price's grandfather, born 1824. TRP archives; owned by Mrs. Moore.

Mrs. Margaret Black, Mr. Price's grandmother, born 1830. TRP archives; photo owned by Mrs. Moore.

Glyndon was a lovely rural town 20 miles northwest of Baltimore with a winter population of about 300. In the summer months, it more than doubled in size, as people fled Baltimore's heat, seeking relief in the relative coolness of the country. The town was perched 750 feet above sea level, considerably higher than nearby Worthington Valley. This elevation helped to cool the air, particularly in the evening, making for better sleeping on hot nights.

According to Glyndon: The Story of a Victorian Village, the town was founded and named in 1871 when the track of the Western Maryland Rail Road (which became the Western Maryland Railway in 1910) from Baltimore stopped there rather than proceeding on to Reisterstown, where the city fathers had refused to have the railroad enter its city limits. The railroad caused the town to grow. It was easy for visitors to come out from Baltimore on day trips and for the men of the community to commute into Baltimore for work. And grow it did, for the next forty years, into large grassy neighborhoods of stately homes with gables, wide verandas, and big sleeping porches.

To the small population of year‐round residents and the wealthy summer crowd were added two camps that were famous locally. They ultimately became well known nationwide and likely would have an important influence on the values of young Rowe. The largest and best known, Emory Grove, was named after John Emory, a Methodist Bishop born in Maryland in 1789. One of the founders of Methodist theology, he rode through the state on the circuit, preaching the Christian gospel. Education was also very important to Emory. He was one of the founders of Dickinson College and Wesleyan College, and Emory University in Georgia is named for him. The camp occupied 160 acres of rolling wooded land. Intended as a quiet retreat away from the “madding crowd,” it was far from quiet. With accessibility provided by its own railroad stop, the camp grew significantly in popularity. The beauty of the setting, and the frequent appearance of famous preachers such as Billy Sunday, drew thousands over summer weekends. In June 1895, it was reported that 10,000 people came to Emory Grove to hear another well‐known preacher of the time, Eugene B. Jones, speak. For those who required at least modest comfort, there were four hotels and more than 700 tents for the rest. The days were given to religious services and teaching, and many nights to the singing of hymns. It is no accident that Rowe and his sisters would grow up as Methodists. On other nights, the younger set took over with parties, games, and much laughter. Although winter evenings were quiet for the Price family, the Grove provided a lot of social activity in the summer. Rowe was acclaimed in his high school yearbook as being a good dancer, presumably based on the practice he got at the Grove.

Close to the Price house was the temperance summer camp run by the Prohibition Party. Mandating total abstinence from alcohol and its “evil” effects, the camp was set up on 18 acres and everyone lived in tents. There was a natural bowl formation on the property, making it an excellent amphitheater where thousands could listen from the grassy slopes. Many good orators spoke there, including members of the Prohibition Party, which ran candidates for U.S. president and was an active third party in the early 1900s. Other entertainment included concerts, poetry, and lectures on many subjects. As Prohibition declined in popularity later in the 1920s and was finally repealed in 1933, the camp adopted the entertainment and educational model of the more famous Chautauqua assembly in New York State. Rowe's father never allowed alcohol or wine in the house.

To paint a picture of life in Glyndon at the time, below are excerpts from Glyndon: The Story of a Victorian Village, in which one of the authors, Jean Wilcox, describes an average day in the summer around the turn of the century:

Days followed a carefree pattern. In the morning we were up early to have breakfast with Papa before he took the 8:05 train to the city and work. Then came the day's chores. The children filled the oil lamps; the mothers canned fruits and vegetables or possibly worked in their flowerbeds.

Everybody in the town retired to the second floor from 2 until 3:30 p.m. The shutters were closed and the streets were deserted and quiet. [Later] the young people played croquet on the front lawns or tennis, while the mothers strolled the boardwalks or met on each other's porches to talk or rock. The town's lively air was largely due to the fact that each street took on a social atmosphere in the afternoon

The Big Event of the afternoon was the walk to the Western Maryland Station to meet Papa who came home on the 5:50 train from Baltimore with other working husbands and fathers. Most of Glyndon turned out at the station every day.

After supper, we amused ourselves with parlor games or recitations.

Glyndon was an active center for sports of all kinds. An ardent Glyndon tennis player was Edmund C. Lynch, whose family summered in the town around the turn of the century. Later one of the founders of Merrill Lynch, he was thirteen years older than Rowe. Though there is no indication that they knew each other well, Eleanor Taylor, an elderly Glyndon resident who had been delivered by Dr. Price some ninety‐two years earlier, recalled that Rowe and Ed often crossed racquets on the grass courts during summer afternoons. Rowe greatly enjoyed the sport and would be an active player until his later years. Lynch, and his later success at Merrill Lynch, may have had some influence in steering Rowe into finance.

One of Samuel Black's grandsons, Rowe's first cousin, was S. Duncan Black, the founder of Black & Decker. Begun in 1910, the company would become one of the leading worldwide electric tool manufacturers for the home improvement market. Growing businesses was apparently in the genetic makeup of the Black family.

Dr. Price's career path differed from that of his father‐in‐law, whose singular interest was business. Rather than heading to medical school right after high school, Dr. Price taught school for several years, as had his own father, before deciding to go to the University of Maryland's medical school. He graduated in 1891, at the age of twenty‐six, and moved to Glyndon to establish his practice.

Helping his clients achieve financial health would be very important to Rowe and a fundamental reason he founded his company. Money was also important to him, but in moderation, so that he and his family could enjoy a comfortable life. He would never drive an expensive car or live in a very large house.

Dr. Price was a good, traditional country doctor, according to Eleanor Taylor. He treated his patients wherever they got sick, often traveling in the evening to distant farms in all kinds of weather. He was fond of telling the tale that after his last call on cold, dark nights, he would often snuggle down into the blankets in his buggy, wrap the reins around the whip handle in its socket, cluck to his horse to begin the trip back, go to sleep, and wake up when the horse stopped at the door to his Dover Road stable. Over the years, Dr. Price became highly recognized in his profession. He was appointed surgeon to the Western Maryland Rail Road that serviced Glyndon, and was also named the Health Officer for Baltimore County, an important honorary post and one that his father had been granted years before. He was a director and then treasurer of the Glyndon Permanent Building Association, an organization of volunteers that provided financing for homes in Glyndon before banks came to the area, and an elected board member of Emory Grove. According to Eleanor Taylor, he was a gentleman, quiet and highly professional. He reportedly had a competitive side that he passed along to his son. According to Mildred's son, Rowe, he had the biggest sled in town, which could outrun any other on its long runners. Dr. Price also did well financially. By 1918, he listed his holdings as 73 acres, three homes, a tenant house, a stable, sheds, two barns, three cars, and a truck.

Rowe's mother, Ella, was a strong‐willed woman and the youngest of seven children. Like her husband, she was well respected in the community and a founding member and the first vice president of the Woman's Club of Glyndon. Originally, this group reviewed books for discussion and was involved in various social activities locally, but as it grew in membership it became committed to more important civic issues. In 1902, the club was responsible for bringing electricity to Glyndon. Later, it created street signs and instituted garbage collection. One could speculate that Ella Price was likely a strong mover behind these activities, given her reputation for drive and getting things done. When a fire destroyed the meeting room of the Woman's Club in the Methodist Church of downtown Glyndon in 1932, Dr. Price would buy the old two‐room schoolhouse to provide a permanent home for the club. It took some courage and the urging of a very determined wife to make such an investment in the depths of the Great Depression.

Rowe was sent off to elementary school at Glyndon School (the same schoolhouse Dr. Price would later buy) at the age of five. As was true until he got to college, he was the youngest member of the class. It was fairly easy for him to walk the mile or so, or to ride the trolley, which ran down Butler Road (Dover Road had become Butler Road by then, which it remains today) in front of his house. His older sister, Mildred, accompanied him. Glyndon School was a red brick two‐room structure with a cedar shake roof and a large bell tower. The interior of the school was grim, with practical brown paint decorating the walls. The rope to the bell hung below the tower and it was fun to pull on the rope when you were asked, but woe to the child who pulled it out of turn. In general, the classes were well disciplined and quiet, at least in the upper grades. Rowe went to first and second grade in the room on the north side; the other, larger room was for the third through the sixth grades. There were two teachers, with the upper‐grade teacher also acting as principal. The alphabet and reading were taught in the first two grades; the multiplication tables weren't taught until the fifth grade. The teachers were strict and a firm rap on the knuckles could be expected if one forgot the product of two numbers. Writing was learned by long practice with handbooks and scratchy straight pens that were dipped into inkwells planted on the desk.

Mr. Price's first school, Glyndon Elementary School, built 1887. Glyndon Historical Society.

In 1909 Rowe graduated from elementary school and entered Franklin High School in Reisterstown. Under the supervision of his sister Mildred, they made their way to and from school by electric trolley. In his sophomore year, there was a school‐wide tennis tournament consisting of fourteen students; Rowe finished second. His years of practice on the grass courts of Glyndon had stood him in good stead. His high school nickname was Doc, suggesting that he intended to follow in his father's footsteps. In his first year there were more than sixty students in his class. By graduation, this had been whittled down to twenty‐three. In later years, Rowe would proclaim that he was “not much of a student,” but he certainly had the willingness to work and the ambition to do at least well enough to get through and graduate in a class with a 60 percent attrition rate.

Mr. Price's older sister, Mildred Price, born 1895. Photo owned by Mrs. Margaret Moore.

He was well liked at Franklin, a bit of a cutup, and the humor editor of the yearbook. The comments under his yearbook photograph read, “His legs are long, he is very tall and ever has a good word for all,” and “It is only his tender years that have saved him from being reprimanded for his pranks at school. His specialty is teasing the girls.” The editor (most of the editorial staff were girls) added, “A day spent at school without Rowe would be a day lost,” and “When he was on the program [Rowe was a member of the Franklin Literary Society] we all looked forward to being highly entertained.”

He was only sixteen when he graduated from Franklin, and his parents decided to send him to the Friends School of Baltimore as a postgraduate student, presumably, to ensure that he got into a good college. Founded by the Quakers in 1784, the school when Rowe attended it was located at 1712 Park Avenue, next to the Friends Meetinghouse (today it is located on Charles Street). Friends remains one of the oldest private high schools in the country. The classes were also small, typically with twelve students, which allowed for a strong interaction with the teachers. At the end of the year, in 1915, Rowe did not finish at the head of the class, according to “T. Rowe Price: A Legend in the Investment Business,” the Baltimore Sun, October 22, 1983, but did well enough to be one of three who were accepted at Swarthmore and the only one of them to graduate from the college.

Swarthmore was an easy choice. His sister Mildred was already enrolled there, it was relatively close to Glyndon, and it had small classes and an excellent academic reputation. It was founded in 1864 by the Quakers, although students of other religions were accepted. In 1906 it formed its own administration and was no longer directly managed by the Quakers. In 1915 many of the qualities of the Quaker church, such as austerity and simplicity, still remained. As a school, it would have seemed like Friends School: the student‐to‐teacher ratio was only eight to one and the overall Quaker philosophy was similar.

When Rowe first traveled to Swarthmore to enter college that fall, he probably took the train from Baltimore to Philadelphia, from which he would have continued on another train some eleven miles up the Main Line. Mildred would either have come with him or would have met him at the station on the edge of the campus.

The Pennsylvania climate could be harsh, so the school was a cold and bleak place in the winter. The original hot‐water radiators were no match for the wind and snow. Heavy sweaters and jackets were the norm, worn daily both inside and out. But on his initial arrival on that autumn day, it was an easy walk through beautiful stands of oak, sycamore, and elm to the lower campus. His arrival is as imagined by the author after a visit to the Swarthmore campus on a bright sunny day early in the fall semester:

Rowe and Mildred walked through the trees from the station to the Magill Walk, lined with oak trees, up the grassy slope to Parrish Hall, built on the top of the hill. They passed small groups of students picnicking and gossiping about their summer and the year about to begin. The bright dresses of the women were splashed with sunlight, adding color to the scene. Parrish Hall, where they signed in for the new school year, was a large building made of locally quarried gray stone. Other than white paint outlining the windows and doors, Parrish Hall, true to its Quaker heritage, was completely unadorned, with none of the Victorian curves and embellishments so popular elsewhere in the early twentieth century. A broad porch supported by white wooden columns extended across a portion of the facade. Students were gathered there, in lively conversation, filling out papers and class requests.

Rowe arrived at Swarthmore with the full intention of becoming a doctor. Not surprisingly, the major reason, according to Mildred's son, Rowe, was due to Dr. Price's strong, unrelenting sales pitches over many years. As the only son, Rowe bore the full brunt of his father's campaign for him to become a physician. It is not certain why he decided not to follow the family tradition. With customary modesty concerning personal matters, he would attribute his change of heart to poor marks. Whatever the reasons, he switched to chemistry in his junior year. Possibly he felt that such courses were an important part of a premed degree and essential subjects for a budding doctor, so credits here might have helped if he later changed his mind and decided to go to medical school. Or perhaps it was to help his relationship with his father. Chemistry was also then one of the major technologies of the future at the dawn of the twentieth century.

Mr. Rowe Price, Swarthmore College junior yearbook, 1918. Swarthmore College.

Despite the large offering of subject matter at Swarthmore, Rowe did not take a single course in either economics or business. When he left college, he was a chemist by training and believed that chemistry would be his career. Although he was referred to as “the electrician” in his Franklin High School yearbook, Rowe never fully developed an interest in the science of electricity at Swarthmore. But in the summer of 1916 he did electrical work at Emory Grove and was paid the large sum of $18.85.

Mr. Rowe Price, Swarthmore College senior yearbook, 1919. Swarthmore College.

A comparison of Rowe's graduation pictures from Franklin High and Swarthmore College shows a clear physical maturation in his college years. Active in athletics, he was the manager of both the football and swimming teams. It was in lacrosse, however, that he excelled. Not only was he on the varsity team in his senior year, for which he won his letter, but, based on reports in the school paper, he became a star player toward the end of the season. He was also active outside of sports. He was a photographer on the yearbook staff, played a major role in the school play, was president of the junior class, and joined the Delta Upsilon fraternity.

By his senior year he had come into his own and was considered to be one of the “big men on campus,” in a phrase of the time. In that era, it was not unusual for a number of students to drop out before completing four years of college. Rowe most likely felt a sense of accomplishment to graduate in 1919, because, as he told us “juniors” at the firm, he was the only student of the three that had been accepted from Friends that year to graduate.

In his later years, Rowe would not appear particularly religious. He did go to church and would later become a Presbyterian, but it would not be a major part of his life. Still, in an interesting way, the adult Rowe would seem to incorporate the values of the “Quaker Way,” and such qualities were certainly part of his family upbringing. He believed in hard work. He was never ostentatious. He believed in the value of women in the workplace. As advocated by Quakers, Rowe would practice all of his life the exercise of both mind and body, and he would be an independent thinker of the first order.

Perhaps most importantly, integrity – beginning with his own personal integrity – would be a guiding principle of the firm that he would form many years later, at a time when integrity would be in short supply in the financial world. As a Securities and Exchange Commission lawyer would comment later to Walter Kidd, one of the founders of T. Rowe Price, “T. Rowe Price and Associates was the gold standard” when it came to its conduct toward its clients.