Chapter Six

BIRTH OF T. ROWE PRICE AND ASSOCIATES, 1937

From here on in this narrative, Rowe will be called “Mr. Price.” After he started his own firm, T. Rowe Price and Associates, he was called Mr. Price by all but his close old friends. It's how those of us in the younger generation addressed him.

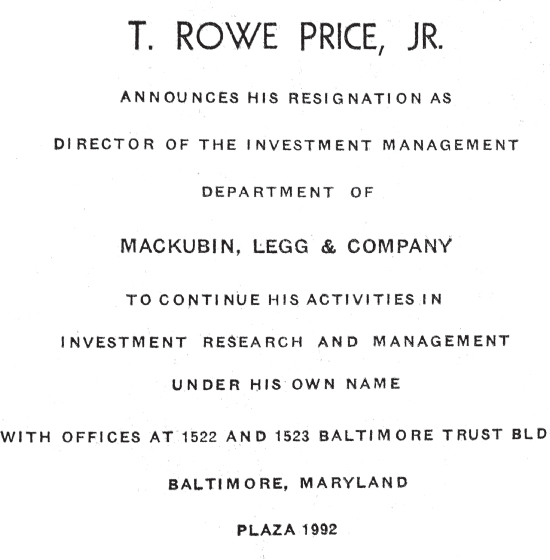

Announcement of the formation of T. Rowe Price, Inc.

After resigning from Mackubin, Legg & Co., and consulting a number of executives both on and off Wall Street, Mr. Price decided to start his own business from scratch rather than work for a more established firm. He believed that his investment philosophy would produce superior results and that working for someone else would only be frustrating in the end. Most importantly, he felt that only by doing the things that he personally believed in could he be happy. He was strongly supported in this by Eleanor. He began to look for an office for his new firm. There was no lack of opportunities in 1937. He ended his search by leasing half of the twenty‐ninth floor in the Baltimore Trust Company Building at 10 Light Street, only a block from his old office. The building had been finished in December 1929, a little over a month after the crash. The Baltimore Trust Company was the largest banking institution south of Philadelphia, and the building was designed to match its reputation. At thirty‐four stories, it was the tallest building in Baltimore. The main floor of its huge public banking room on the ground level was laid out in mosaic tile, with large murals on the walls by prominent local artists, depicting scenes from Baltimore history. Its exterior was classic Art Deco, similar to the Chrysler building in New York, with gargoyles peering down at Light Street. The roof was copper, which had quickly turned a beautiful green, interlaced with thick beams plated with pure gold.

10 Light Street. Photo by the author.

The bank began to have financial difficulties early in the Depression and never reopened after the 1933 bank holiday. Its failure resulted in a bankruptcy totaling a figure in excess of $20 million (approximately $374 million in 2018 dollars) in losses.

The shareholders of banks that went bankrupt in the 1930s not only lost their entire equity investment in the bank, but they could also be assessed for as much as the par value of their stock to repay the debts of the bank – par value being the price below which a corporation would not issue shares, as stated in their prospectus. This price was deemed by the court to be $5 per share in the case of Baltimore Trust Company.

At that time, a bank's officers and directors were normally held accountable for a bankruptcy. In the case of Baltimore Trust Company, the court held the directors to be personally liable for their grossly negligent acts, in that they failed to exercise proper supervision. The directors were some of the leading businessmen of the city, according to the Baltimore Sun. Yet they were all sued. In total, another $250,000 ($4.7 million in 2018 dollars) was eventually extracted from the directors – a stark contrast to the lack of a similar fallout after the financial crisis in 2007–2008. According to the Center for Public Integrity: “In the seven years since the financial crisis, none of the top executives at the giant Wall Street banks that fueled and profited from the housing bubble have been personally held to account” (Alison Fitzgerald, May, 22, 2015).

The bank vacated 10 Light Street in 1935. Shortly thereafter, Maryland's Public Works Administration moved in, but the rest of the building remained empty. The only tenants that were expanding in those days were either government agencies or those directly connected with local, state, or federal government. As a result, when Mr. Price signed the lease in mid‐1937, he had plenty of potential space for expansion. Although he no doubt hoped that some of his accounts would continue to employ him at his new firm, this was not a certainty, given the economic environment. He was not closely tied to the Baltimore social elite, which was an important source of potential new clients.

The building was in an ideal location, close to the Baltimore financial establishment, but not directly in it, as befitted his concept for the new firm. The structure was elegant and thus served to impress potential new clients. Mr. Price's office, which had been designed for the president of Baltimore Trust Company, had beautifully crafted woodwork, including many broad wooden mahogany shelves, a big desk, heavy, carved chairs, and a comfortable leather sofa. The views were impressive, facing east over the city and the financial district to the outer harbor. To the south, he looked toward the bustling inner Baltimore Harbor. The other, much smaller corner office also faced the outer harbor and would soon be occupied by Charles Shaeffer. The rest of the staff was in the open area in between, except for Marie Walper, who had her own small office next to Mr. Price.

Ms. Marie Walper. TRP archives.

His official separation from Mackubin, Legg did not take place until June 30, but Marie followed him to their new quarters before his resignation in early June. She was the first employee, although she initially didn't receive any salary. She well understood his frustrations at Mackubin, Legg, as well as his ambitions for the new firm. It was a real vote of confidence in Mr. Price that she would leave the relative safety of her old job, at the age of thirty‐three, to join his new firm in the midst of the Depression, especially as she knew that the new firm would operate based on a concept that had only lost money at Mackubin, Legg. Her spouse offered her some security, as he had a good job as a salesman at the H. J. Heinz Company. This extra income would come in handy in the future. When the firm's income failed to cover expenses in its early years, she would not only be able to forgo her own salary, but to loan the firm a little money. She would voluntarily do so on several occasions, to cover items such as modest Christmas bonuses, for which Mr. Price would later give her full credit in recounting the early history of the firm. In his journal, he mentioned that she once offered to lend her Christmas Savings Club money.

On the morning of July 1, 1937, Mr. Price would have punched the button beside the ornate brass elevator door for the express to floor twenty‐nine. The firm was born with an official announcement in the Baltimore Sun. There was a great deal to do immediately after Mr. Price and Marie took over their new office. First came the legal structure of the new firm, for which Mr. Price chose a sole proprietorship. He wanted to be clearly the boss from the outset. In the most diplomatic but positive manner, he and Marie had to quickly notify Mr. Price's clients of his change in status before it became known through Baltimore's efficient rumor mill. Finally, they had to move twelve years of his personal files and papers from one office to another. (Mr. Price was a strong believer in extensive records, charts, bulletins, and correspondence.)

A month later, Isabella Craig also made a break from Mackubin, Legg. She became the head, and only member, of the T. Rowe Price Statistical Department, where she tracked the financial data of the firm's investments. She lived at home with her parents and was thus better able to handle the financial risks of the early years of the firm. Walter H. Kidd and Charles “Charlie” Shaeffer, the two other official founders, did not arrive until January 3, 1938. Peter Shaeffer, Charlie's son, recalled that their delay in joining was entirely due to money and not a lack of confidence in the new company. Mr. Price could not afford to pay them through the organizational phase of the business, before there was any income coming in. Charlie and Walter had no other source of income, and Charlie had recently married his childhood sweetheart, Ruth Smyser. It must have been a particularly difficult decision also for them to leave a relatively secure nest and fly over to the thin, shaking bough on which Mr. Price's new firm perched.

Isabella Craig. TRP archives.

It is also possible that the six‐month delay in employing Walter and Charlie could have been due to external events. When Mr. Price opened his door for business on July 19, 1937, the Dow Jones Industrial Average stood at 170. On August 14, it rose to 190 and then proceeded to plummet, in the sharpest bear market since 1929. It appeared to bottom in November and, by year‐end, it was holding its ground at 120. The market ultimately bottomed on March 31, 1938, at 99. This sharp decline possibly gave Mr. Price some brief second thoughts about his timing in starting a new business.

The two men who joined the new firm in January would prove to be nearly as essential to its success as Mr. Price himself. It's worth going into some detail about each of them – their background, education, and skills.

Charlie Shaeffer was born in Bridgeton, Pennsylvania, outside of York, in 1910. His father started out as a tobacco farmer and at one point had his own cigar company as well, but he lost everything in the crash and the Depression. Charlie enrolled at Penn State on a scholarship that included working three separate jobs simultaneously. He also supplemented his income by playing bridge for money. He won his varsity letter on the tennis team, and was president of his senior class and of his fraternity, Alpha Sigma Phi. After graduating in 1933 with a degree in commerce and finance, he got a scholarship to the Harvard Business School from an anonymous member of the Harvard Club of Maryland. Following his first year at Harvard, he needed a job and Mr. Price was looking for an analyst for the summer at Mackubin, Legg. In 1934, there were very few such jobs. The unemployment rate was at an all‐time high of more than 25 percent, not including those on part‐time work or forced to work on reduced salaries. The two men hit it off. Like any good aspiring salesman, Charlie could sell himself well in an interview. He was hired by Mr. Price to work in the research department at Mackubin, Legg on a study of the tobacco industry, a subject with which he was very familiar. When he graduated with an MBA from Harvard in 1935, he was offered a job as a full‐time analyst at Mackubin, Legg. He ultimately found himself working closely with Mr. Price as he began to bring in clients to the Investment Management Department. Charlie soon moved out of research to become an investment counselor, working directly for Mr. Price.

Charlie Shaeffer. Property of Pete Shaeffer.

In most ways Charlie and Mr. Price were opposites, and the differences were why they made a good team. Charlie was outgoing and informal. He was very good with people and made friends easily. Mr. Price was much more reserved and prickly. Charlie was intuitive; Mr. Price was analytical. It was very natural for Charlie to become involved in new sales while Mr. Price focused on investment strategy and investing.

In an interview conducted for the firm's fiftieth anniversary, Charlie said that he was attracted to the investment counseling business because he saw how his family's life was totally upended by the poor investment decisions made by his father in 1929. “To me,” he said, “it seemed that there should be some way to invest money in securities more intelligently and with greater prudence, which would reduce the magnitude of investment losses by the investment public in a poor economy, and afford the possibility of producing a good return over the longer term.”

Walter H. Kidd, the third founder, was born in 1907 on a farm near Columbus, Ohio, where his father raised dairy cattle and had commercial orchards. His first jobs were farm chores, including feeding the chickens and acting as a midwife for the cows. He attended local schools and then Ohio State University, majoring in architectural engineering, and graduating in 1929. He worked for two years at the Mount Vernon Bridge Company in Ohio designing bridges, until it was clear the bridge business was closing down in the Depression. He needed a new career and fast. A friend suggested Harvard Business School. The last bridges were being designed at Mount Vernon just as Walter entered the gates to Harvard Yard.

Walter Kidd. TRP archives.

When Walter graduated, the economy was worse than it had been when he entered. He received no job offers. He was, however, interviewed by Joe Bent, then the head of equity research at Mackubin, Legg, who, due to a mix‐up, had arrived at Harvard to do recruiting interviews after the class had graduated. Walter was one of the few still on campus. He didn't hear back from Joe, but wrote him a thank‐you letter and took a short consulting job offered by a professor at the business school. The letter seemed to trigger Joe's memory and he offered Walter a job at Mackubin, Legg as a securities analyst.

Unlike Charlie, Walter was quiet and introverted. He had little social life outside of occasional dinners with the Prices and the Shaeffers. He was, however, smart, hardworking, and detail‐oriented. He developed into a first‐class financial analyst. He did not marry, so he had considerably more free time than Mr. Price or Charlie. In addition to being an analyst, he assumed the roles of acting administrative director, chief financial officer, and in‐house counsel, as well as the young firm's only research analyst. He kept the company's books, filled out the various forms and filings associated with the business, took care of those internal matters for which a lawyer was not required, and performed the research on most of the companies in client portfolios. He was a valuable, busy, but uncomplaining member of the team.

Walter was also the secret soul of the company. Growing up in the heart of the Midwest on a farm, he had developed a strong sense of right and wrong. In his mind, there were no gray areas and no cutting of any corners. Although Mr. Price always operated to the highest business and personal ethical standards, there were moments he might weaken, such as when faced, for example, with endless government red tape or a quicker way to get a complex job done by cutting a few perfectly legal corners. At such times, there would erupt from a corner of the boardroom table, “Just a damn minute!” and a forceful Walter Kidd, his face flushing red, would face down the boss. With Walter, there was only one way to do business – the right way – even if it took longer and was more expensive.

Walter, in the opinion of the author, who worked under him for his first several years at the firm, was one of the best true analysts in the business at that time. He could very accurately ferret out the pluses and minuses of a corporation as an investment. He generally left the exact timing of an investment to Mr. Price's finely tuned sixth sense. They made a very good team. He had left Mackubin, Legg because he shared Mr. Price's belief in a long‐term, research‐driven investment approach. He had recognized that when Mr. Price left, the firm would move to a more common, trading‐oriented investment format where real long‐term research was not so important.

The economy in the 1930s would continue to follow the stock market closely. Industrial production fell almost 30 percent from mid‐1937 throughout most of 1938. Unemployment jumped from 14 percent in 1937, a recovery low, back to its 1933 Depression high of 25 percent, in what would be called the “Roosevelt Recession.” With an eye toward the 1940 presidential election, Roosevelt reversed his move toward financial conservatism, and once more increased government spending. The economy recovered, and the stock market obediently followed, rising through much of 1938. It would not decline again until the end of 1939, when World War II got underway in earnest in Europe.

Mr. Price knew that a new investment counseling organization had to clearly show above‐average performance if it was going to be successful. To demonstrate this, he had established three “model accounts,” as he called them, prior to starting T. Rowe Price. The performance of these portfolios would be the company's major sales tool at its inception.

The first model portfolio was started many years before in 1926, just after Mr. Price and Eleanor were married. It was called the Diversified Investment Portfolio, and was Mr. Gherky's personal account. It consisted of growth stocks, corporate and tax‐free bonds for income, and short‐term government securities for safety of principal. Its objective was growth of both principal and income. It represented the account of the typical wealthy businessman – which would be the firm's primary marketing target in those early years.

The second model account was the Price Inflation Fund, begun in 1934 to test Mr. Price's Growth Stock Theory. Its goal was growth of capital and, secondarily, growth of income. Later, the name was changed to the Growth Stock Fund and, after 1937, consisted primarily of Eleanor's inheritance from her father.

The third portfolio was the William D. Gherky Trust Fund, originated in 1937. Following Mr. Gherky's death, the Philadelphia's Girard Trust Company was the trustee, but it was managed by Mr. Price, and consisted of growth stocks and tax‐free funds. It was structured as a “balanced” portfolio (roughly 50 percent stocks and 50 percent bonds).

Over the years, Mr. Price would start a number of such model portfolios to test different investment strategies. In several cases, much later, they became the basis of new mutual funds. Each of these model portfolios was carefully tracked and updated on a daily basis by the firm's statisticians. The three original model portfolios were also audited by outside firms on an annual basis.

With these model accounts Mr. Price could, therefore, at the outset of the firm, present a longer‐term record of performance, whether the new client's goal was growth of capital and income as befitted a wealthy executive, a more aggressive portfolio of all growth stocks geared for a younger person, or a more conservative trust account, where income and preservation of capital were both important. In coming years, he would often refer to the performance of these model portfolios in his bulletins to clients and newspaper and magazine articles. They were, thus, vital marketing tools.

In addition to these track records, the new firm had one other initial asset. Some of Mr. Price's old clients did indeed come to the new firm and entrusted it with at least a portion of their assets. As the performance of these portfolios continued to be strong under the management of the new firm, these clients added more capital over the years. In the same pattern that he had developed at Mackubin, Legg, they became some of his best salesmen, recommending him to their friends.

In years to come, Mr. Price would often remind younger counselors that, by providing superior performance to their clients and excellent account service, they were creating their own future potential income stream. Service to the customer was the single most important concept that was drilled into every new employee: “If you treat the customer right, he will reward you longer term.” He frankly told new counselors that should they ever decide to leave T. Rowe Price for any reason, a significant number of his or her clients would follow, lending him or her credibility and instant cash flow. Mr. Price's other important keys to his success were a reputation for integrity, professionalism, and innovative, strategic thinking.

The original stated goals for the firm appear modest in retrospect, but they seemed very optimistic at the time. These were to ultimately attain 399 accounts, generate $310,000 in fees, and manage the business with a staff of 28. Such a firm would be profitable, produce reasonable salaries, and Mr. Price could easily manage it. Running a large organization or generating a large stream of income was never important to Mr. Price. His ultimate goal was simply to produce the best investment record in the country. He was very competitive. He liked to win. In later years, many of his young associates would feel that he was even competing with them! There were few words of encouragement or congratulations for a good job, only suggestions that they could have done better if they had but followed his ideas more closely. He was indeed a tough boss. Fortunately, Walter or Charlie was there for a pat on the back and the mention of a job well done.