Section 6: Capturing the Human Element

Photographing the People Behind the Machines

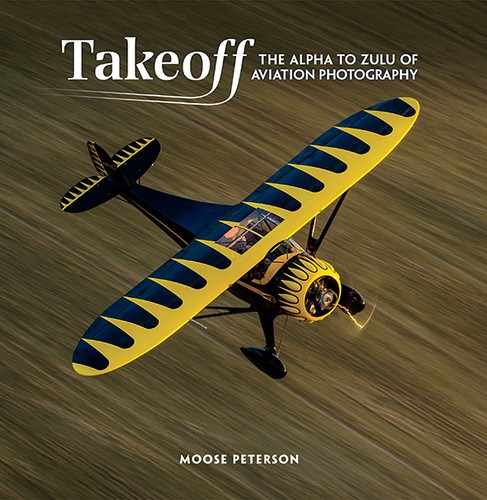

Last minute prep at Grimes Field | Shutter Speed: 0.5 sec

The USS Hornet’s radio operator intercepted a message in Japanese at 07:45; its origins were close. SBDs (carrier-based scout bombers) launched earlier off the USS Enterprise had spotted a small Japanese fishing vessel, and then later flew over the Enterprise’s deck, dropping a message and causing Admiral William “Bull” Halsey to immediately change course. At 07:38, a patrol vessel had been spotted, so with the radio interception and sightings, the hand was dealt. Halsey had no option; he ordered the USS Nashville to sink the vessel and then flashed a message to the Hornet: LAUNCH PLANES X TO COLONEL DOOLITTLE AND GALLANT COMMAND GOOD LUCK AND GOD BLESS YOU.

The 70th Doolittle Raiders Reunion

The Doolittle Raid on Japan, 18 April 1942, was a high risk, all-volunteer, first and last time experiment. Not designed so much as a major strategic strike, the goal—which was accomplished—was to demonstrate to the Japanese people that they were not untouchable. Eighty men, led by Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle from the US Army Air Force, launched in 16 B-25B Mitchells from the deck of the Hornet that morning. Their story is one of the great accounts of patriotism, youth, and determination, which was celebrated on 18 April 2012 in Dayton, OH, at the 70th Doolittle Raiders Reunion!

Of the 80 volunteers who made up the Doolittle Raiders in 1942, four of the five living Raiders attended the celebration: Lt. Col. Richard E. Cole, co-pilot of B-25 #1 (Doolittle’s co-pilot); Maj. Thomas C. Griffin, navigator on B-25 #9; Lt. Col. Edward J. Saylor, engineer/gunner on B-25 #15; and Staff Sgt. David J. Thatcher, engineer/gunner on B-25 #7 (as of the writing of this book, only Raider Lt. Col. Dick Cole survives). All these heroes, in their nineties, were an inspiration, and you could always tell when they were present with the round of applause and the large crowds, straining to say thanks for their service.

The Doolittle Raiders with the B-25J Maid in the Shade crew

While the formal Raiders Reunion was at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, it started informally at Grimes Field in OH, on Saturday the 14th, as the B-25s for the memorial flyover on the 18th began arriving (some didn’t make it in until Monday due to weather). Twenty B-25s from around the country flew in to participate in the ceremonies. Present were (in order of flight; and pictured on the next spread):

» B-25J Panchito – Mardela Springs, MD

» B-25J Pacific Princess – Chino, CA

» B-25A Miss Hap – Farmingdale, NY

» B-25J Russian Ta Get Ya – San Antonio, TX

» B-25J Betty’s Dream – Houston, TX

» B-25D Grumpy – Mukilteo, WA

» B-25J Axis Nightmare – Batavia, OH

» B-25D Yankee Warrior – Ypsilanti, MI

» B-25J Executive Sweet – Ventura, CA

» B-25J Special Delivery – Galveston, TX

» B-25J Champaign Gal – Urbana, OH

» B-25H Barbie III – Marathon, FL

» B-25J Tondelayo – Stow, MA

» B-25J Take-Off Time – Philadelphia, PA

» B-25J Old Glory – Coulterville, CA

» B-25J Miss Mitchell – Baxter, MN

» B-25J Show Me – St. Louis, MO

» B-25J Yellow Rose – Midland, TX

» B-25J Maid in the Shade – Mesa, AZ

» B-25J/PBJ-1J Devil Dog – Midland, TX

Along with their B-25J Betty’s Dream, the Texas Flying Legends Museum (TFLM) brought in their A6M2 Zero, P-51D Mustang Dakota Kid II, P-40K Aleutian Tiger, and FG-1D Corsair. The roar of engines could be heard to the crowd’s delight Saturday through Monday, as B-25 flights for the public were conducted and the TFLM put on a show one evening. An estimated 10,000 folks came to Grimes Field to celebrate the Raiders and see the largest gathering of B-25s since WWII!

P-40K Aleutian Tiger

On Tuesday morning, a rare sound rattled the city of Urbana, as the 20 B-25s started to turn over at 06:40 for the scheduled 07:00 launch to Wright-Patterson AFB. Larry Kelley of Panchito organized the Gathering of B-25s at Urbana and led the brief the night before the flight. At the beginning of the brief, we were honored to have Navy Chief Petty Officer Allen Josey, an electrician on the Hornet the day the Raiders launched for Japan, recount his stories to us. It was a great way to put into perspective the mission of the next couple of days. It can’t be stated enough the dedication and determination of these B-25 flight crews to be there for the celebration. Some flew for 12 hours through very nasty weather and some, like Grumpy, didn’t arrive until late Monday night.

I was incredibly fortunate to make the flight that morning in the nose of the AZ Commemorative Air Force’s B-25J Maid in the Shade. It cranked at 06:53 and taxied into position for takeoff. At 90-second intervals, the 20 B-25s roared out of Grimes Field and flew to Wright-Patterson AFB, where they landed and parked wingtip-to-wingtip, staging for the massive group portrait of aircraft and crews. Then, the gates opened at 10:00, and the crowds flooded in. It was great to see young and old, strolling among the B-25s, asking questions, examining the planes, and buying t-shirts from all the crews. At 17:00, the four Raiders arrived and went down the line of B-25s big-eyed, looking at the planes they flew 70 years ago over Japan and thanking the air crews for flying them in for the ceremony. Once the crowds left for the day, the B-25s were turned over, taxied to the end of the runway, and parked like they were on the morning of 18 April 1942 on the deck of the Hornet.

The flight deck of the B-25J Maid in the Shade during the flight to Wright-Patterson AFB

It was a gorgeous morning on the 18th, quite the opposite of that morning 70 years ago. At 12:20, Panchito was the first to take off from Wright-Patterson, and then one by one, in the same order they launched from Grimes Field the day before, the 20 B-25s took to the air to start forming up for the flyover. The fences surrounding the field were packed with onlookers, taking in the sights and sounds of the launch. Michael Polly of Pacific Princess said that while forming up over Dayton, he could see people coming out of office buildings, getting out of cars, and looking up. It was simply an amazing sight!

At exactly 13:00, the waves of B-25s started to fly over the memorial site where the four Raiders watched. In echelons of four, the B-25s roared overhead against the blue backdrop, the white-cloud-dotted sky. There was hardly a dry eye on the field, as the sound of the flight thumped in our chests. As they flew past, you could see the B-25s turn clockwise and form up for their second pass. In an even tighter formation, the B-25s came back overhead. As the last echelon passed over the field, we saw a flight of four continue on around clockwise over the field. A few minutes later, Panchito, Betty’s Dream, Pacific Princess, and Miss Hap performed a missing man formation, with Pacific Princess pulling up and out of the formation. (Sixteen of the B-25s returned to Grimes Field after the flyover at Wright-Patterson; four flew back home.)

This was the start of the ceremonies, which continued on at the memorial directly afterward and didn’t end until Friday. During that time, the Raiders were at various luncheons, banquets, autographing sessions, and functions. It was great to see these gentlemen be honored by thousands of people! A very stirring moment occurred Thursday morning when the Raiders came to Grimes Field for a breakfast to say thanks to the B-25 aircrews for all they did to make the celebration and flyover happen. Cole, Thatcher, and Saylor attended, talking with crew members, and then posing with each crew for portraits. You’ve never seen so many smiles or heard as many laughs, as stories were exchanged between then all.

Lt. Col. Edward J. Saylor, Maj. Thomas C. Griffin, Staff Sgt. David J. Thatcher, and Lt. Col. Richard E. Cole

Lt. Col. Richard E. Cole

When they were asked to volunteer for a high-risk mission, more than 80 men put their lives on the line. Not until they were on the Hornet, steaming to sea, did they know for a fact they would be taking the war to Japan. Their dedication was honored by the dedication of the 20 B-25 flight and ground crews who journeyed to Dayton to fly overhead for only a few minutes. It wasn’t about the aircraft; it was all about those who were in those aircraft that day and those who put the aircraft into the air. But in those minutes, they said a lifetime of thanks from a country forever grateful for this sense of duty 70 years ago when they launched off the pitching deck of an aircraft carrier. The Doolittle Raiders Reunion has occurred many times in past years, with the 75th happening in April 2017. Only one Raider, Lt. Col. Dick Cole was there to hear the thanks, once again, for what they did for this nation!

The Hardest One

When I was writing this book, I saved this section to write last because I knew it would be the most difficult for me to write. Obviously, from the Doolittle Raiders Reunion story you just read, I have managed to make strides in photographing people, but this was not always the case. I was hoping that if I left this section for last, I’d have such a head of steam from writing the rest of the book, I would just cruise through this most critical section in the success of an aviation photographer. Such was not the case. It was not easy for me to write. There are so many variables here, the biggest one being you.

RV formation over Kissimmee, FL

This section began with a lengthy intro for two reasons: First and foremost, if a socially inept person such as I can get through this, there is hope for all. Second, is to demonstrate the rewards for breaking through and understanding just how important photographing aviation folks is to your aviation photography. Just think of working with pilots at an air show as a required skill. Lastly, it’s to underscore just how important I think this is above all other photographic techniques.

It All Started with Dudley!

Two years prior to our being a part of the Doolittle Raiders Reunion, I was at the greatest gathering of aircraft: Oshkosh. My mind was naturally on aircraft. The problem was I was focused in on only the aircraft; I had blinders on about everything else. Take it from me, that’s a major problem you must avoid! The first day, I was obsessed, to say the least, for many reasons and under great pressure to produce. I saw nothing but aircraft, despite being in an ocean of 20,000 aviation enthusiasts. At the end of that first day of shooting, I was feeling horribly frustrated with my results. As I sat in my chair with my computer plugged into the outlet outside at the community showers, my images left me feeling pretty low.

The next day, our band of three was up before the sun, out of our tents, and amid the WWII bombers, shooting as the sun first greeted us. I was determined to do better than the day before with my camera. The weather was typical Wisconsin in the summer, hot and muggy with big rains erupting throughout the day. The rains had chased us the day before, starting up right when the sun hit, so the second day we were prepared. When they started that morning, we got ourselves over to our usual breakfast tent, ordered some breakfast, and sat down to wait out the downpour. The mess tent on Warbird Alley, which can easily hold 200 people, had perhaps a dozen folks, mostly warbird pilots getting ready for the day. With the rain pounding down on the tent, our band of three sat by ourselves as breakfast was put down in front of us.

Quick Brief

Have business cards in your pack ALL THE TIME and give them out like candy!

We were sitting and eating breakfast surrounded by an ocean of empty seats. The aircraft behind us in Warbird Alley were deserted, as the pounding of the rain started to let up. There was no movement, as most were still either asleep or hiding from the rain. I was staring out at the P-51D Mustangs right outside the tent when, the next thing I knew, this gentleman plopped down right next to me. He had the biggest smile, and like the majority of nice folks at Oshkosh, gave us a warm greeting.

Scottie, being the bold member in our little band, struck up a conversation with the gentleman, who we instantly learned was Dudley. Well, Dudley talked planes with Scottie and Kevin for quite some time, and in the tradition, they became fast Oshkosh friends. With me being new to the whole thing, when Dudley said he flew up to Osh in an RV, it had me wondering—I didn’t know Winnebago had gotten into the airplane business. It sounded like quite a flight from the south that Dudley had to make to get to Osh, and it wasn’t his first time. He must be quite the pilot, I thought, as I listened. The sun had started to shine again and life was starting to stir in Warbird Alley. We all had finished breakfast and, with our twentieth cups of coffee, said our goodbyes and went our own ways. We headed back to the ramp where the warbird jets were parked. Scottie and Kevin had a good laugh when I asked about a flying Winnebago.

We began walking the line and I was looking for, yep, airplane photos. With the gray skies and blacktop being all wet, I thought I might be able to make something unique happen photographically. Walking down the line of jets, we came to the A-4 Skyhawk. This was my first up-close encounter with the Skyhawk, a great looking airplane, so I was checking it out closely. I didn’t know much about the A-4, so it intrigued me, especially its odd tall stance. There was visual, photographic stuff everywhere. But, I was already getting frustrated because, while there were great subjects like the A-4, it was flat light. I had no story to tell with my camera! I was walking entirely around the Skyhawk, trying to make lemonade from a situation I thought was hopeless.

Our band was standing on the tarmac in front of the Skyhawk jet just watching all the goings on, as pilots and ground crews were getting the aircraft ready for the day’s flight. I was staring at the Skyhawk, wondering just how I was going to get the shot I so desperately wanted. While looking at it, I saw a guy who appeared to be the same one from breakfast, Dudley, behind the A-4, talking with the pilot of the Skyhawk. They soon shook hands.

He walked closer to us, and I saw it was indeed Dudley, so when he had a moment, I walked up to him and asked him if he had flown the A-4. Oh yeah, he flew the A-4 and a whole lot more! Ninety minutes later, I had become fast friends with Dudley, and he had shared some great stories with me. Near the end, I asked him if he would like to have his picture taken with the A-4. The twinkle in his eyes and smile on his face was all that was required to make the photo happen.

Dudley had just taught me a momentous lesson I’m passing along to you. I went to Oshkosh, one of the greatest gatherings of aircraft in the world, thinking it was all about the planes. I couldn’t have been more wrong. My conversation with Dudley turned into many email conversations later. Following the prints I sent him, came a signed copy of his book to me. The giant lesson: aviation photography is all about the people, and thanks to Dudley, I found this out early in my aviation career! The rest of my Oshkosh week was something very special, full of people and plane pictures! Thanks Snake!

They Don’t Fly Themselves!

Perhaps I had blinders on, or perhaps I just wasn’t seeing them in other’s images while doing my homework, but for whatever reason, it required Dudley to bring the message home. These planes don’t fly themselves! It takes a high level of dedication and passion to keep antiques, warbirds, and GA aircraft in the air. It is easy to get caught up in just the machines. They are, of course, what first catches our attention, but it’s the men and women in aviation that keep them alive, while sharing their history with the next generation. To move our photography forward, in every sense of the word, we have to get to know these folks behind the aircraft and help tell their stories in our photographs. And, while this seems so obvious, it’s not. And, making it work is not that easy either.

Dudley with the A-4 Skyhawk

If there weren’t enough challenges with just shutter speeds and light, we introduce what, for some and definitely for me, is the scariest aspect of photography: working with people. I’ll admit that just walking up to a stranger and introducing myself and asking, “Can I take your picture?” is not my forte. It’s easier for me to climb Mt. Whitney than go ask a stranger to stand in front of my camera. But, as you can see from the Doolittle story, I’ve made some strides in this department over the years, and I want to share with you how I did it. It might help you and, in turn, improve your aviation photography and tell the stories of some amazing people and their aircraft!

T-33 Shooting Star

Getting Right Down to It

Here’s my secret to success that has gotten me so far, so quickly: with business card in hand and knowing, I mean really knowing and not guessing, that I have the photograph, I have a very simple line I say to pilots, “Email me and prints will follow!”

I found out very quickly that pilots and plane owners love prints. I’m not talking about quick prints from your local drugstore. I’m talking large 22x17” or larger 24x30” gallery-quality prints of gorgeous images of their aircraft. I did this with my very first air-to-air subject, Dennis Buehn’s T-6 #33, just to say thank you. I had no idea the ramifications of doing it, but it taught me an incredibly important lesson. Here’s the caveat, though: I’m a master printer, with inexhaustible printing resources. It’s an advantage that I have exploited to make up for my lack of social skills. Putting prints in the hands of pilots makes all the difference in the world!

It’s kind of a catch-22: you need great images to make great prints, and you use printing to learn to make great images. Really, prints are the key to making great aviation images and, in turn, those prints are key to working with pilots! I have seen some folks whose content is so hot try to use this idea to gain amazing access, until their image quality shoots them down. I’ve seen some with good content, but great quality, use this simple idea and go on to make killer images on amazing projects. This might seem the opposite of what is needed when working with aviation folks, but it’s the heart of our success. The principle behind this is really simple: we’re demonstrating our passion for aviation, talent, and skill in photography to the people we want to work with, while saying thank you to them at the same time. Moral: learn how to be a great printer!

Quick Brief

I use Epson printers, profiles, ink, and paper because they make my images come to life. My favorite paper: Platine. I keep it simple and it just works.

Paul at Fantasy of Flight in Polk City, FL

For Me, It’s Just Like Working with Biologists

I am often asked, “How do you get in with biologists on a project?” I find that answer is the exact same as the answer for working with pilots. You start with understanding the project, critter, or in this case, the specific aircraft you really, really, really want to work with. Not picking one because it’s cool, but one you are willing to invest your time, money, talent, and passion into. Once you have that aircraft in mind, you start doing your homework—and not to be an expert on a particular aircraft, but simply so you can communicate. For example, when someone says they flew to Osh in an RV, you shouldn’t be thinking Winnebago!

You then start photographing the aircraft type or the specific plane you want to work with. You get a feel for the aircraft, apply all we’ve talked about in this book, along with your passion, and you start making some solid, clean clicks. You rely on those solid clicks, and not Photoshop, to make images that are standouts. This gives you the confidence to take the next step.

This is when I recommend you make your move. You might have to stand around for a long time until you see your opportunity, but after doing your homework, you approach the owner/pilot. You have a business card in hand. You might have an iPad with a bunch of your images loaded (again, the vast majority of pilots have an iPad). And, here is where my direct help comes to a halt because it’s now up to you and your photography, because once you introduce yourself, you’re writing the script on how it all unfolds. You will have your foot in the door with those images, so now it’s up to you to walk through it. I can tell you, though, that at the end of the conversation, no matter how it goes, I always hand my business card to whoever I’ve been talking to and say, “Email me and prints will follow.”

Something to Ponder

Let’s step back a second now that you know the end game. How do you make your photographs stand out from the guy next to you? How do you start to get those images of the pilots and crew to have images to show them? Perhaps the guy next to you has a passion for the same aircraft as you. You might feel some competition (which really doesn’t exist, except in your mind) and feel you need to get ahead. Is there a way? Of course, have the better photographs, but where do you start? Here’s a thought: You’re shooting at the end of the taxiway to get those takeoff images we’ve talked about. Typically, pilots taxi down with the cockpit open, helping the pilots keep cool while being able to see where they are going. This open cockpit is a great photographic opportunity for you!

Larry in a Ford Tri-Motor

Casey flying the P-51D Dakota Kid II

When they just jump into the cockpit to fly or as they taxi the aircraft by, or perhaps in the warm-up area, get the photograph of the pilot in the open cockpit. You’re going to need a longer lens, a 400mm or longer, to get this shot, as they can be at some distance and you want a tight crop. You can easily get the shot of the pilot concentrating on their craft. You can also often get them looking out of the cockpit as they taxi, making sure the route is clear. You might also wave at them. Quite often, they will wave back, and while that’s a good shot, it’s the moment they stop waving and put their arm back in the cockpit, but continue to stare at you that can be the really cool shot.

Walt in his Ryan

Tony flying the CAF Dixie Wing’s SBD Dauntless

It’s a Small World!

Just like with biologists, aircraft owners and pilots are a small community! This means all the good things you do will help you move forward. One good contact and the relationship will blossom to many more. This is the best part; it just takes the first one to break the ice, and then you can keep moving forward. This was essential for me, since this is not my forte. On the flip side, one goof-up and it’s a long road back! It can be done, but as is with human nature, bad deeds, no matter how small and insignificant, are hard to forget.

This is where those prints really can make the biggest impact. The number of times pilots have pulled out the prints I have sent them and shown them to their pilot friends, well, I’ve lost count. What I think of as the biggest business card in the world, makes a huge impact. What makes a bigger impact is the fact that you carried through with your promise and delivered the prints. The one thing that gets more photographers in trouble is making a commitment to deliver images/prints and never going through with it.

Quick Brief

A good problem to have, but be prepared for when your prints are such a hit, you are asked for more than you are fiscally comfortable with giving away. What do I do when this happens? Go in the red and spend the money.

Like biologists, pilots are very professional, disciplined folks who are all business when they are at their craft of flying (they all fly for the sheer pleasure of it). This means you need to be professional, as well. This encompasses all aspects, from the times you approach the pilots (or don’t) to all the commitments you make and deliver on. Just remember, it all starts with the photograph.

The Easy Human Element: The Crowd

Where do you start making these images I’ve been talking about? At this point, you should be asking yourself this, as some of what you just read has, in a way, been covered. Like everything photographic, there is no clear-cut, straight path to success, so I want to thoroughly cover all bases. Air shows are a target-rich venue when it comes to people pictures. I have seen some amazing people images taken at air shows; I’m still working on joining those ranks. It requires something I’m not really good at: focusing in mentally to the possibilities. I think you have to be thinking about spectators as subjects to find the subjects. You’ve gotta be looking for that family watching the air show—the unique hats and outfits, the expressive face—and then put that with the event to tell the story. The best are little kids doing something uniquely kid cute. That’s a skill and talent I’m working on.

Quick Brief

Pencil and paper work wonders! Having a pad and writing down notes, names, and promises is probably the best equipment you can make sure is always with you, next to business cards!

The aspect to this that is really important is the storytelling. While the folks draw you into the photograph, it’s placing them in context that I find equally challenging. Here’s one of the few examples I have to show that demonstrates my point: you’ll often find reenactors at air shows, most taking their craft very seriously. What if the aircraft you really want to work with is a Focke-Wulf Fw 190, and there is a reenactor dressed up in a German uniform (even if it’s a soldier and not pilot)? In this case, I walk up and talk with the reenactor (building people skills) and get him to stand in front of that Fw 190 to take a cool, quick snap. With that snap, if you talk with the pilot of that Fw 190, and you have that cool photo of the reenactor with the Fw 190, you’ll instantly make a positive impression.

Reenactor with an Fw 190

Generations looking at the F2G-2 Super Corsair

One of the challenges you will have is finding those great faces in the crowd that are being hidden by it. This is not too dissimilar to landscape photographers’ problems, but in reverse—having people in their photographs they do not want. The solution to both problems is the same: time. This is a perfect example: the generations looking at the F2G-2 Super Corsair. At times, they were hidden amongst others also admiring the Super Corsair. Just waiting a few minutes, those others left, leaving just the generations standing there. Since this plane is now gone, the obvious story at the moment I took the photo, years later takes on a whole new meaning. This tactic at times does not always pay off, but when it does, you can get the photo.

Quick Brief

Show guides are an invaluable tool to learning about aircraft, owners, and pilots and should always be purchased. At the very least, you’re supporting the event that’s providing you with photographic opportunities.

Mike on the cowling of an FG-1D Corsair

Making the Folks Visibly Pop

Light is still the very best way to make a subject pop, but we can’t always count on it the instant we need it. So, the next thing we should talk about is f-stop. A shallow DOF is the first, and often the best way, to make folks pop out in a crowd. Next is a longer lens—a 105mm or longer. And then there is the very best: a longer lens with a shallow DOF. The 70–200mm f/2.8 is a great lens for this task and one I used for many years. Of late, I turn to the 105mm f/1.4, which is a killer tool for making folks pop. Its shallow DOF and narrow angle of view permit you to isolate the person while relating them to the background to tell the story. In the image on the previous page, as Mike worked on this FG-1D Corsair, he hopped up onto the cowling. The 105mm f/1.4 makes him pop (along with the light), while telling the story.

How do we make this work for us on a continual basis? It really is no different than what we’ve already talked about, other than we are adding one more element to our shot list. We are still looking for the great light, we are still looking for the clean background, and we are still looking for the aircraft. We are just going to incorporate a person into the formula we have already created for our aviation photography. In other words, in our aviation storytelling, there must be a human element. The key here, though, is to go beyond just adding the human element by including their story in your visual story.

When it comes to making a person pop, it can be done by engaging with a subject (the pilot or someone else), and then asking them to pose with the aircraft. Doing this will require you to possibly talk with the pilot of the aircraft (if not the subject), as well as the subject, to use the plane for a backdrop and the subject as a model. For example, I was working with an FG-1D Corsair, an important aircraft in the Pacific during WWII. It was tucked away in the back of a hangar. So, while there was gorgeous light streaming in from the open hangar doors, the setting was less than ideal. Then, in steps the human story.

Claude, a WWII vet and Corsair pilot

Claude Hone is so typical of many WWII vets. He served simply because it was the right thing to do. Claude is not a hero, not an ace, just your basic aviator who did his job under some of the most difficult conditions—ones we could never imagine—and came back home to help build a country afterwards. I had the honor and pleasure of spending quite a bit of time with Claude over three days (as well as his delightful daughter, Nancy), while in Sioux Falls, SD, attending the Sioux Falls Airshow. Originally, it was just going to be for an afternoon to record his story on video and take his portrait. Well, we all simply seemed to hit it off and for the next three days, Claude wowed and amazed us with story after story.

Claude was very proud, even in the 100-degree hangar, to show he can still wear his flight jacket from WWII. Though he will be 96 years young (and doesn’t seem a day past 16), he talks about his days flying a Corsair from Henderson Field on Hell’s Island (Guadalcanal), and then P-51Ds with former SD governor Joe Foss in the South Dakota Air National Guard, like it was yesterday. With Claude, though, it’s the brief stories that get you. He still has the original aviator watch the Marines gave him 72 years ago, and it’s still ticking. The watchband, though, that’s the real piece of history. It’s made from the skin of a Zero, shot down at Henderson Field, that he has had all these years! We met some amazing and memorable vets that weekend, but it was Claude who we struck a real friendship with—an amazing gentleman and vet, and a true American that we now call dear friend!

Arizona Ground Crew Living History Unit reenactor with the B-17G Sentimental Journey

Scottie’s another dear friend and a marvelous reenactor who is part of the Arizona Ground Crew group. These amazing troops of WWII reenactors are a favorite of mine to work with, and Scottie is a natural. Again, the goal is to tell the story of the ground crew and their charge, a B-17G. The first thing is to understand you don’t have to show the entire plane or person to tell the story. This scenario happens often at air shows, if you look for it. Shooting with a 70–200 at 200mm and f/2.8, with Scottie standing some distance from the B-17, we can isolate Scottie while still telling the whole story. It’s very simple technique you can apply either by accident or design.

When I started shooting aviation, walking up and talking to these folks to make photographs was a huge challenge. I remember asking Sharon to talk to someone first, opening the door, as it were, for me. After a decade, I’ve gotten better at walking up and talking to someone, getting them to be part of my visual story. So, if I could get past that horrible awkward stage, you can too!

This Brings Us to Gear

I’ve mentioned two lenses already, the 70–200mm f/2.8 and 105mm f/1.4. And, while these are great lenses for this, they are not the only options. First, you must think about your budget and back. The 105mm f/1.4 is a great example, as it is not an inexpensive lens nor lightweight, so adding it to your camera bag takes some real thought. On the other hand, the 70–200mm f/2.8 is a lens most already have in their bag as part of their aviation gear, so the problem is already dealt with. But, just as I have the 105mm f/1.4 along for this specific task, there are other lens options for you to consider.

Where the long lenses (200–400mm) work great for what I think of as “sniper portraits,” wide-angle lenses are great for the “larger” story. The 14–24mm and 24–70mm are two excellent examples of lenses that are part of the basic aviation gear and work really well for portraits. When it comes to designing your own bag of gear, you need to think about how you like to take portraits (which might be something to determine, as well). If you like to pull the subject out from the aircraft, often you’ll need a longer portrait lens to help eliminate unwanted elements getting in your photograph. If you want your subject up near the aircraft, then you’ll want the wider lens to take in more of the aircraft. For the latter, I carry the 24mm f/1.4 AF-S with me to go wide and have the narrow DOF.

How do you figure this all out prior to being with the aircraft and the subject? One simple way is, again, using a car in place of the aircraft and practicing! Start taking practice portraits, trying all of this and more—all your imagination can conjure—to determine which style you like best. And then, practice, practice, practice until you have the final results you want. At the same time, you can determine your strengths and weaknesses in your portrait photography, so when you have that great moment, all you have to think about is the story and not the technique.

The Scariest Piece of Gear

When it comes to making the common uncommon in our photographs and isolating the subject, flash is a powerful, powerful tool! The issue is that flash adds a whole new layer of complication to everything we do. There’s physically carrying the flash with us all the time, having its batteries fully charged, and then pulling it out in a heartbeat and applying it. This, and much more, makes it the scariest piece of gear.

The vast majority of the time, we are using it as flash fill, filling in shadows that might be hiding details we desire in our photograph. With that said, don’t pigeonhole using flash to just this one role. Light is light and the more you can use light to tell your visual story, the stronger your photography will be. Whether you’re photographing a pilot, pilot and his plane, or a spectator, flash can be an essential tool.

Because it is so important, I have my SB-5000 Speedlight in an outside pocket of my Mountainsmith sling bag all the time! Shooting with the D5 in aperture priority, I have –1 exposure compensation dialed into the D5 for the SB-5000. So, if I put the SB-5000 into the hot shoe and just turn it on, I have flash fill exposure ready to go, nothing to think about. Flash in the hot shoe is often a last resort lighting solution, but when you’re pinched for time, it’s your fallback. With the D5 wireless iTTL, this is an option that I love to take advantage of whenever time permits. This permits you to move the flash quickly from the hot shoe for more dramatic lighting. You could, for example, have a pilot in a cockpit and place the flash in the cockpit with the pilot, and then shoot at a distance and control it from the camera.

The takeaway from this for you is to make friends with your hot shoe flash! Start small and simple, both in the flash unit and your practice. Get comfortable with it all, and then slowly push yourself to bigger and scarier scenarios. Knowledge is power, so the more you know about flash and how you like to see it, the better your photography will become!

Light for the Portrait

We are the servant of light. In aviation portraits, we have two complicating factors: light on the aircraft and light on our pilot. Artificially lighting an aircraft is a major undertaking, so the majority of the time we use available light for lighting the aircraft. This is simply a matter of size and the power of the lights versus the size of an aircraft and time management (there are some photographers light painting aircraft, which is really cool!). A single, hot shoe flash isn’t enough to light an aircraft, but it is for the pilot, so we need to start this process looking at the overall light.

The best light is one where you don’t need to use flash in the first place. A soft, overcast light is a good place to start. With this, the aircraft has minimal shadows and you can use the fuselage of the aircraft to bounce light into the subject, making them visibly pop more. This is a simple and fast way to make a clean portrait at an air show when you only have a minute or two. Using this lighting and technique, you’ll more than likely be using a wider than longer lens, and getting the subject close to the aircraft.

Quick Brief

You can manipulate the light in a hangar via its doors. Play with how wide and which one is opened or closed to manipulate the light.

Bob and his gorgeous, homebuilt Starduster Too

Ken in a Cessna 182RG

One of my all-time favorite kinds of light is found working back in the depths of a hangar when the hangar door is open. This is another great option for soft, directional, and dramatic light. The beauty of this is if you place the aircraft halfway back in, and the pilot between the door and the plane, the light falls off between the pilot, plane, and background and looks like a million bucks with very little effort. The first drawback you’ll think of is you won’t find a hangar on a flight line of an air show. But, if you talk with the pilot, keep this option in the back of your mind because it is a possibility after the air show that’s quick and easy. Both of these options are important because you have to do all the lighting, along with everything else, by yourself and normally in a heartbeat or faster!

What’s a quick, easy, gorgeous way to light both the plane and the pilot? Those golden hours of light—sunrise and sunset—of course! Their soft nature and warmth just can’t be beat. You can take advantage of this light by remembering you can turn the aircraft so it, and the pilot, are in the best possible light. But, while it’s a great light for us, the time it’s available can work against us. What makes taking advantage of this gorgeous light a challenge is, most of the time, you won’t find pilots up with the sun, and in the evening at an air show, they typically have other things going on. This light is too gorgeous to pass up, so you always have to try. The one thing you have going for you is time with this light. You can tell your subject you only need them for a second, since there is no complicated lighting to set up or calculate.

Quick Brief

You might find it easier to walk about an event with your remote TTL cord already attached to the flash and basic settings dialed in, so getting your setup working fast is easy.

But, as you might imagine, we won’t be working in the best of light. We will have to make do with whatever is presented to us because we are always pushing the clock. This is when we need to bring in our hot shoe flash. As I mentioned, we can’t light the whole plane, but we can light up our pilot, so we need to use light management, along with our storytelling. Since you can’t practice every possible scenario, here are a few ideas you can tuck in the back of your mind to pull out when appropriate:

High noon—some of the contrastiest light of the day! The pilot is available for five minutes. How do you make the shot? If you have any way to create a shadow or take advantage of one, do it! In the shot on the left, I had the pilot sit in his Cessna and used the shadow from the wing. It was easy from there. I used the SB-5000 to bounce light off the bottom of the wing and into the pilot. Here’s the key to this: the flash isn’t the only bounce light. The plane was positioned so the cement in front of the plane is also bouncing light up into the pilot and the plane. It’s helping the power of the flash by doing some shadow fill-in. Remember that cement can be your lighting friend, as well as foe, depending on how you use it.

Overcast skies, as seen below, can be a great light for aircraft. If there is any texture or mood to the clouds in the sky, you can incorporate it into the background, which is even better. This is when you make the ambient light your fill and flash your key light. With today’s iTTL, this is really simple to do: Set the exposure compensation for the ambient light (in the camera body) to –2/3 or –1 stop, and then set the compensation for the flash (in the flash) at 0. Take a quick test shot to check this combo. You can take this a step further by gelling the flash, so its light is a tad warmer than the overcast; I prefer a simple 81A gel. This little extra warmth sets its light apart from the colder light of the overcast.

This is the classic scenario you will get asked to do more and more, and you’ll get known for working with folks as much as aircraft. Keep in mind that getting asked to do what we call “pickup portraits” is a compliment and means you’ve been doing things the right way. The pickup portrait scenario usually goes like this: “We need you to take a picture for us. We have so-and-so at our plane, and we want our portrait taken with them. Can you do it?” The answer is yes, but then you must deliver. That was the case when I was asked to photograph Tuskegee Airmen Col. (Ret.) Charles McGee, Lt. Col. (Ret.) George Hardy, and Lt. Col. (Ret.) Alexander Jefferson.

German reenactor in a Spitfire Mk. IX

Lucky for me, the CAF Red Tail P-51C was on the field; unlucky for me, was it was pretty much high noon on a bald sky day. I went to basics, as I only had a few moments to make the click. Pickup portraits never seem to have any time; they are always done in a rush. The camera exposure compensation for the ambient light was set to –1 2/3. The flash compensation was set to 0. I turned the three so their baseball caps created a little shadow on their faces, and then used the flash to light up their faces while underexposing the rest of the scene. No, it’s not amazing lighting, but the subject matter is, and it was an honor to be asked to make the portrait.

Charles, George, and Alexander, Tuskegee Airmen, WWII vets

If you want to do yourself and your photography a favor, learn to use flash! There are many great options to do this, and the best I know are Joe McNally’s online classes from KelbyOne.com. He has lots of classes on small flash in situations that might seem totally off the wall, until you work with pilots. Once you watch those classes, take what works for you and your gear and skill, and practice, practice, practice. It’s probably not a skill you think of as important for photographing aircraft, until you use it!

The Pilot Portrait Project

One just never knows where things will lead in photography! I’ve gotten over the initial shyness I had when I first started aviation photography, and you could say it has swung completely to the opposite side. I’ve been amazingly fortunate to make many special friends since starting this aviation journey. The majority of them have an inner passion for aviation that goes beyond just flying. It was this inner passion I wanted to celebrate and honor, if I could, in a photograph. It meant going where I hadn’t been for a long time, setting up big shoots, and using big light. And, at first, it was just for a single article I was writing.

Chris and his L-5 Sentinel, a WWII-veteran aircraft that flew over the beaches of Iwo Jima during the American invasion

I started with a most reluctant subject, a dear old friend, Chris. To say he’s camera shy is an understatement. Just like it would be to say he has a passion for aviation, history, and sharing that with anyone who wants to learn. He was a natural. We ventured to his home airport to photograph him with his L-5—a very special L-5 that flew over the beaches of Iwo Jima on landing day on 19 February 1945.

Don’t let what appears to be a complex shoot scare you off. The most complex thing here was keeping that Profoto B1 and 8-foot Octa from launching in the wind and hitting the L-5. They were weighted at first with my snow chains, since those were handy, then we added 20 pounds of water weight, and finally Sharon! Once the light was set up, we just had to wait for the sunset to set the clouds on fire to get that blood red sky. With the thought that this would be just a single “big” portrait to go with the rest of the article, I kept it simple with the one big light. As it happened, it turned out well.

Perhaps it turned out too well, because it gave me the courage to attempt other portraits. Next, I ventured to Kansas to photograph my dear friend Scottie with the then-prototype Cessna Citation X+ (now a production aircraft). Scottie was the main test pilot for the X+ program, so it was only natural to photograph him with that plane. Being the test pilot for the program really helped to get access to the aircraft, and then permission to tug it out in the dark and position it just for this portrait.

But, I need to back up a moment. As this idea grew, so did the stories and, therefore, the lighting gear. Like I mentioned before, you can’t light an aircraft with one hot shoe flash. You sure can with 20 of them, but that requires time, which is always at a premium. At the same time, since for a majority of the shoots it’s just me and not me and a group of assistants, the whole affair had to be manageable by just me. That means getting the gear from the office to the airport and flying it all commercially, across the country to the site, setting up, breaking down, and flying it all back to the office. The Profoto B1 2-light kit was perfect for this because it has the power, portability, and flexibility to get the job done while producing gorgeous light.

There are two lights being used on Scottie’s portrait: The first one, the main light, is using the Magnum 50° reflector with grid and is gelled with an 81A. It is lighting Scottie and light falloff is lighting the front of the X+. The second light has a strip box and is lighting the side of the X+. The landing lights are also being used as fill. This was all set up in the dark, and we waited for the sunrise to burst to make the final shot. Emphasizing the public’s perception of test pilots, it’s shot at a low angle with Scottie pulled out way in front. The 24mm f/1.4 AF-S was used to wrap it all up into one clean click.

The setup for the final portrait on the facing page

Two years later, and the article that turned into an article series has now grown into a long-term project heading for a book. With more than 30 portraits in the can, the lighting has stayed simple, using two Profoto lights as the main light and ambient light as fill the vast majority of the time. I’m sharing the portrait of Larry, on the next page, to make a different point. Larry is another dear friend that I’ve had the good fortune to do many shoots and air-to-air photo missions with. Until you read the section in the pilot portrait book (which is in the works) about him, you won’t know all that he has accomplished in aviation or all the aircraft he has flown. For example, Larry is the pilot who flew the Super Corsair Race 57 for the Epson Finish Strong campaign I shot. Where I normally make the suggestion for what aircraft I want to use with a pilot for his portrait, I let Larry make the call since there were too many options for him.

Scottie and the Cessna Citation X+

Larry selected his neighbor’s and dear friend’s P-51D Mustang Big Beautiful Doll as the aircraft to represent his passion. A gorgeous Mustang, its polished fuselage with nose art dictated how it was parked, where it was parked, and the sunset setting for the final photograph. On the next page, you can see the two lights being used: the strip light was gelled with an 81A and the Octa was straight white light. Getting Larry to smile is no challenge, so the shoot went quickly and smoothly.

But, getting to the point of how you just never know the entire story you’re creating and preserving, about a month later Big Beautiful Doll went down with its owner and a passenger, both being lost in the tragedy. It was pretty devastating to Larry; he had lost another dear friend to an aviation tragedy. This simple portrait now had new meaning, and that’s the point. Photographs are all about memories, and while we want them to be happy reminders of great times, there are times they can take on a whole new meaning that is even more powerful.

Larry with the P-51D Big Beautiful Doll

The Profoto lighting setup for Larry’s portrait

The Rewards Are Priceless!

After my experience with Dudley, I started to do all the things I’ve mentioned here, and everything else I could think of, to be more involved with the folks behind the aircraft. A part of this is getting to know many of the folks in the warbirds community. This process has led to many great friendships and associations, like those from the Doolittle Raiders Reunion. Another is one I had with Robert Odegaard, who I’ve already mentioned. What he did in the field of warbird restoration is nothing short of amazing. Many of his aircraft, like the P-51D Mustang Cripes A’Mighty, have won numerous National Aviation Heritage Invitational awards. He was also known for his restoration of the F2G-1D Super Corsair Race 57—the Cleveland Thompson Trophy racer is a classic, as well as rare bird. In 2011, Odegaard was finishing up his latest restoration, the Thompson winner F2G-2 Super Corsair Race 74. (This is just another story about Bob, of the many, from our short time working together.)

I had become friends with Bob and his son Casey (who I still do a lot with) a year before and Race 74 came up in conversation during one of our air-to-air missions. In their hangar in Kindred, ND, they were bringing back to airworthiness their second Super Corsair. At the time, I had not been a part of a restoration project, though the mechanics behind the whole process fascinates me to no end! It’s an art form all in itself and the Odegaard family is the best. Well, I asked Casey if he could let me know when Race 74 was ready for its first run up, and I would try to get to Kindred for that day. On 21 June 2011, I got the call, and the evening of the 23rd of June found me in Kindred.

The 24th was a magical day for me. I spent nearly 18 hours in the hangar, shooting thousands of images and learning volumes from the guy who wrote the book on restoring warbirds! I used every body, every lens, still and video, during the day, photographing all that was going on. I arrived in time to see the prop installed, engine turn over, brake test, and the last bit of details wrapped up. As Bob said, “You have the only photos of the pipes still chrome” because once that R-4360 turns over, they will turn from bronze to black.” And, I was there when that prop first turned. Later that year, I was there when Race 74 flew at Reno (even got to be crew for five minutes), and we did the first air-to-air mission with it, then later an air-to-air mission with Race 74 and Race 57. And then, we lost both Bob and Race 74. This aviation photography, it’s all about the people!

That’s an Affirmative!

Aviation photography is like no other genre of photography on the planet! It combines all other genres into one package that simply gets the adrenaline pumping. And, it’s a genre of photography everyone can get involved in simply, inexpensively, and quickly. I’ve only begun to scratch the surface of the potential in these pages! Looking at the great aviation photographers out there, we know that even the sky is not the limit for where we can take our cameras. It seems every day there is a new technology, a new technique, a new aircraft, or a recently restored warbird that starts the cycle all over for us. And, we can do this, along with the thousands of other aviation photographers right alongside of us. I truly hope the next time I’m on the flight line, smelling those fumes and watching those aircraft take to the air, you’re there standing next to me. I know that with this book and your passion, your start into aviation photography will take flight!

F2G-1D Super Corsair Race 57 and F2G-2 Super Corsair Race 74