Introduction: The Skies Are Not the Limit

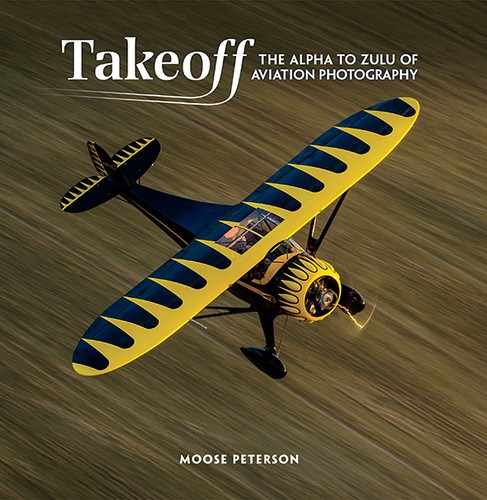

Sharon flying in a Waco QCF

For me, I haven’t gotten close to that limit that started decades ago. We’d gathered our stuff from the station wagon, the whole family in tow, as we walked toward the entrance. I was perhaps six or seven, holding my dad’s hand, while walking in, and boy was I excited to see the planes! It was an overcast day with the sun just starting to make its presence felt on the morning. The roar that seemed to be off in the distance soon went screaming past and I looked up just in time to see fire coming from the back of those “fast planes.” My dad looked down at me and said, “Those are the Blue Angels and they are just the start,” as we watched them fly off into the warmly lit haze and disappear from view. That was my first air show at Point Mugu, CA, and I was hooked!

My father’s start was at age 16 in ROTC for what was then the Army Air Corps and when WWII started, he was right there flying. He wasn’t a pilot, though, he flew a Cub that someone had on base. He was a navigator/bombardier in a B-29 in the Pacific during WWII and Korea. Like many, he was a kid going off to war, and like so many, the camaraderie it brought was life changing. He and his crew and squadron mates lived and breathed aircraft! My memories from the rest of that day at the Point Mugu Air Show, other than being scared to death by the surprise and low pass of the Blue Angels, are of sheer fun! For the next decade, while sitting around a campfire in the backcountry of the Sierra, my father told me stories of those days in the B-29 and the aircraft that protected them.

I still have his flight jacket, plane ID books, and training manuals. Inside of them are my drawings I did as a kid, trying to bring those aircraft closer. On Sundays, my family would go to LAX, walk up to the departure gates, and watch the planes and people come and go (an era long gone, sadly). My dad would tell me more stories and solve some of the mysteries of flight for me. I have no doubt that in the sharing of all of his stories, my father’s romance with flight and aircraft planted the seeds.

What Draws Us to Aircraft?

There are a thousand reasons why a photographer first begins to pursue one particular genre of photography over another. In my case, it was a chance comment that got me pointing my lens at an aircraft in 2008, and the bug finally bit after 25 years of pointing my lens at critters. Now, you might think it’s a guy thing, but such is not the case! I know a lot of great lady aviation photographers who are really, really good and have been at it a whole lot longer than me.

So then, just what is it? Why do we photograph aircraft? I live in the Sierra, which is part of the flight path during the summer for the NAS Fallon and NAWS China Lake F/A-18s. The valley reverberates as the F/A-18s pass overhead. And nearly without exception, as they do, heads turn skyward as folks scan the skies to catch a glimpse of a plane as it roars past. Those who find it in the sky point upward and smiles appear. Airplanes are a part of our lives in some way or another, from the movies we watch, to how we travel from coast to coast, to simply flying overhead. Leaving earth with our imaginations or in reality, flight tugs at our heartstrings in a unique and special way.

Photographers have overactive imaginations! Thank goodness, as that creates all the images we enjoy taking, viewing, and sharing. Photographers are also collectors, not of coins or stamps, but of images that contain the wonders they see that spark their imaginations. And photographers by nature are very curious, often using their cameras to find the answers to questions. I think this is the genesis of why most point their cameras at aircraft, what we affectionately call when birding, “Silver Gashawks.”

We’ve produced a number of KelbyOne.com classes on aviation photography, even a movie (which you can watch for free at kelbyone.com/books/warbirds). We’ve received a lot of response from folks watching them with the common comment, “I never thought about photographing planes until I watched your classes.” Planes are perceived as being out of reach of most photographers when nothing is farther from the truth. And that’s because we normally see planes way up in the sky, where the longest lens on the planet still renders them as micro dots in the viewfinder. For some reason, most air shows don’t do a great job of making their presence known, so the idea of getting close to aircraft, for the purposes of photography, just doesn’t leap out at us.

Because the response has been so great to the KelbyOne.com classes is partly why I wrote this book, but it gets to the heart of the question, “What draws us to aircraft?” I think understanding the answer is an essential ingredient in making the spectacular images we take. Without that answer, we’re merely going through the motions and being satisfied with an image only because it’s sharp. There is so much more satisfaction to be gained from our photography!

The answer to the question is simply: “We wonder what it’s like to be at the stick, flying like a bird.” It’s that answer that we need to incorporate into our aviation photography! Setting our viewers’ imaginations loose in a spirit of wonderment when looking at our photographs makes flight come to life for us. For most of us, we won’t ever be physically behind the stick (most pilots have cameras, so we’re not alone in this quest), so we need to bring that to life in our photographs. Our imaginations permit us to, though, from the moment we have that aircraft in the viewfinder, the moment we go click, and the moments afterward when we enjoy that photograph! Whether the plane is on a stick, parked on a ramp, or flying overhead, when we have that great click of it, our imaginations put us in the pilot seat, soaring above the earth and going as fast as our imaginations let loose!

The Romance of Flight

Understanding this answer is so important to our photographic success! We need to incorporate it in every one of our photographs to move them beyond what others standing beside us might be capturing (that sounds bad, but that’s the game, right?). When we do that, it leaks out of our photographs and grabs the imagination of the viewer, and that’s how we begin to visually tell stories.

Understanding this answer inspires us to push beyond the “Here’s a parked plane” to “This plane soars with the clouds,” even when the plane is parked. And while we’re just playing with semantics here, the make or break of a photograph hinges on the same tiny nuance. This is when the brain has to take a right seat to the heart, which then flies the plane!

AT-6 Texan

Many have asked, causing me to wonder and find the answer, “why I have had such success so quickly as an aviation photographer.” There are three answers to this question, with number one being romance. While I think aircraft are amazing industrial art with lines, shapes, textures, and sounds that rival the finest art hanging on a wall, you can’t exactly hang a plane on a wall and admire it (though I know of someone doing just this). But we can hang our aviation prints on the wall and they can, and need to, contain all the romance that makes that industrial art a flying aircraft.

This has to be the greatest challenge facing the aviation photographer! How do you bring romance to a piece of cloth, wood, plastic, and metal, especially when some were made for the express purpose of waging war? This is where the answer to “What draws us to aircraft?” comes into play. We have to move past the technical and that, in itself, is a challenge for many. Making that f-stop do more than just communicate sharpness and shutter speed, more than time and light, more than whites and blacks, pushes us. And that’s a good thing! We need to move to that area of the heart; our aviation image must encompass romance.

Aeronca 7AC, Piper J3C-65 Cub, Piper PA-11 Cub, and Taylorcraft BC-12D

SNJ-5C Texan and P-S1D Mustang

The Challenge of Bringing Movement to Stills

And if this weren’t enough to scare off the mere mortal of an aviation photographer, we also have to give flight to our still images! Why do we photograph planes? It’s to put ourselves and our audience behind the controls of a plane and that means it’s moving, flying!

While what I present in this book could be used, in part, for video production, the main focus is stills. A still, that moment in time forever gone, but recorded in a heartbeat by our camera, is a frozen point in time that means something to us. Whether perceived or in reality, aircraft don’t freeze, but are in constant motion. Yet our images are not moving.

How then do you bring motion to a still image? Cutting to the chase, the answer is shutter speed and background. But, being a photographer, you know that there is no simple, one-word answer for solving our photographic problems. There are buts, ifs, ands, ors, perhaps sprinkled liberally, and that’s because we are all individuals with unique ways of telling a story.

I alluded a moment ago to there being three things I attribute my quick success as an aviation photographer to—number one was romance, next is wildlife, and lastly, is landscape photography. Thirty years of photographing critters instilled in me certain techniques, tools, and thoughts, which I’ll fully share here, permitting quick access to aviation photography success. In my mind, I treat the plane itself as a critter. Landscape photography is how I treat everything else in the frame. If you’ve read any of my work, you know I stress backgrounds and aviation is no exception! When you combine romance, wildlife, and landscape styles into a photo of an aircraft, you are able to achieve success because that piece of metal is no longer just a piece of metal. That brings movement to a still image of a moving subject!

And with that, it’s time to put fuel in your photographic engine and get that prop turning!