8

Sourcing the Expertise You Need

Deep down, buried beneath all the challenges and opportunities of measurement that we have described, lurks a pointed question: How do you source the expertise you need to do it all?

Measurement is—or at least should be—a technical business. So to do it well, sooner or later you either need to have technical expertise yourself or access to someone else who does.

We call it a “pointed” issue because organizations often struggle with it. Many, especially smaller firms, lack internal expertise and so rely on external experts. Yet choosing and managing technical vendors when you do not have expertise yourself has its challenges. An increasing number of larger companies therefore employ internal experts. This approach is not devoid of challenges either. For starters, there is more than one type of measurement expertise, and knowing which you need is not always clear. Then there is the matter of how best to position, structure, and deploy this resource.

In this chapter, we look at these issues. They are critical because without access to the right expertise in the right places, decisions made about whether and how to do measurement are unlikely to be sufficiently informed. And in our experience, the single biggest factor holding businesses back from making measurement work better for them is a lack of understanding.

We begin by looking at the options in sourcing expertise. We then turn to the issue of how to select, contract with, and manage vendors.

Sources of Expertise

Organizations have four basic options when it comes to sourcing the expertise they need to select, manage, and use measurement:

- Use vendors.

- Appoint independent, freelance consultants.

- Train HR personnel.

- Employ their own experts.

Many small to medium-sized businesses have little choice in how they approach the issue. The extent of their measurement use does not justify employing an expert in the field or training internal personnel, so they have to rely on external vendors.

For slightly larger businesses, however, there are two additional options. First, they can train key personnel (usually HR) in particular methods or tools. For example, HR managers are often trained in the use of psychometric tests. This enables the informed use of particular tests and saves money in the long term by avoiding the need to use external vendors.

But no matter how skilled these individuals may be in the use of certain methods or tests, this kind of training does not provide deeper technical expertise or a broad overview of the market. So another option for companies, which is increasingly common, is to have an independent expert help them navigate the measurement market. These are specialists who have worked in the field for a while and are familiar with the vendors in it. Their role is different from that of vendors in that they act only as advisors and do not become involved in delivery. They typically assist firms in identifying who and what to measure and which vendors and tools to use. They can also advise on how best to extract value from the outputs. Obviously their involvement adds to overall costs. The benefit of using them is that it can help ensure that the investment in measurement is money well spent.

For larger businesses, there is another option: employing their own experts.

There are five types of role that technical experts often play within organizations:

- Deliverer. A few large organizations have their own in-house assessment delivery teams. Sometimes they focus only on a particular process, such as running assessment centers for graduates. At other times, they may deliver a range of services. Research into the cost benefits of in-house delivery is limited, but it appears to be no more expensive than using good external vendors. The main benefit of employing in-house teams is the extra control it brings over quality. There is also a suggestion that since these people have better knowledge of the business, they can make better judgments about how well individuals fit, although no definitive research has yet been done to test this assumption. Moreover, since this in-house role offers less variety than a similar role with a vendor, firms may struggle to attract and retain the best assessors.

- Designer. Although it is increasingly rare, some organizations design their own methods and tools. The most common elements designed are interviews, assessment centers, and 360-degree feedback tools. Rarely, companies may also design their own psychometrics. The role, often combined with a delivery role, obviously requires considerable technical expertise.

- Manager. More common is appointing in-house experts to project-manage measurement processes and oversee the work of vendors. These individuals are usually in middle-level positions in the center of businesses, although they are sometimes employed by specific business units. The role rarely touches on measurement strategy; instead, it focuses on specific measurement projects or processes. The idea of using experts rather than generic project managers is that their expertise will enable them to ensure better outcomes are achieved. One common risk here, though, can occur when a vendor is appointed and championed by a senior executive. The vendor may believe that it reports to this individual rather than to the expert, thus compromising the expert's role. In our experience, therefore, this role can deliver real value only when manager-experts have genuine control and authority over the activities of vendors.

- Broker. The internal broker role sometimes contains elements of the manager role, but it also involves the expert acting as an internal consultant. The role is typically positioned at the center of a business and is often referred to as a center of expertise. Brokers are a resource for the whole business and can advise on all matters relating to measurement. A common scenario is for a business unit or team to ask for assistance in obtaining a particular measurement process or tool. A broker can then consult on what type of solution will meet the business's need and help select and purchase the best tool or service. The role can therefore provide a useful lever for driving consistent practice across a business. Brokers can set standards, ensure good data collection, and promote effective use of measurement results at a local level.

- Strategic owner. The final, increasingly common role filled by experts is that of the strategic owner of talent measurement. It often includes elements of the manager and broker roles but extends beyond them. Strategic owners are responsible for developing an organization's measurement strategy and policies. They often own many or all of the organization's assessment processes. And, critically, they are responsible for leveraging measurement data to inform other people processes. The big benefit the role brings is that longer-term and cross-unit interests, such as the creation of talent intelligence, can be better served.

For the strategic owner role to deliver these benefits, however, two things need to be true. First, the person must be both a measurement expert, with deep technical understanding, and a skilled organizational operator who can influence at senior levels. It is increasingly common for nonspecialists to head up HR areas, including talent management and learning. Whether this is ever advisable for any area is debatable, but for measurement it absolutely is not. No other area is quite so pervaded by deeply technical issues. And unless individuals understand them, their effectiveness will be compromised.

Second, the role must be positioned correctly in the organizational structure. It is important that strategic owners sit outside any recruitment, learning or development teams. This is because when they reside within one of these teams, the role invariably becomes siloed within that team. For example, we know one head of assessment who works in a large global corporation and reports to the recruitment director. The intention was for his role to focus on all aspects of measurement, not just hiring. But since the learning and development heads view him as part of recruitment and want to retain control of their own areas, they tend to avoid working through him whenever possible.

Even when experts are employed at a supposedly senior—and therefore more strategic—level, their role often ends up being fairly tactical in nature. And it is this lack of expertise at a genuinely senior level that accounts for many of the implementation issues we have described. It is why strategy is often missing, why data are so infrequently used, and why practice tends to vary across firms. Far too few large businesses that have expertise have it in the right places.

Types of Experts

Part of the reason that companies lack sufficient technical expertise has been their lack of understanding of the value that talent measurement can add over and above merely supporting individual people decisions. Seen as a tactical and almost operational issue, it has been treated and positioned as such. Another part of the reason, though, is the dearth of suitable expertise. On the face of things, there is no shortage of experts, but finding one with the right mix of skills is not always easy.

Groups of Experts

One way to think about the type of expertise required is to consider three overlapping groups of experts: industrial/occupational psychologists, psychometricians, and consultants:

- Industrial/occupational psychologists (I/OPs). Psychologists who specialize in operating in businesses are known as industrial or occupational psychologists and they are often certified by national associations. Their training, and therefore their overall approach, is primarily driven by research and theory. There are two main communities of I/OPs: academics, who work in universities and business schools and undertake most of the research, and practitioners, who work in consultancies or directly for companies. As a profession, they bring deep technical knowledge and a broad understanding of the various measurement methods. Yet they are often accused of lacking pragmatism and of overly focusing on best practice at the expense of fit-for-purpose practice. An example of this is their advocacy of structured interviews described in chapter 4. In our experience, this characterization is probably not fair for the profession as a whole. Indeed, some of the profession's own most prominent members have spoken out on the issue, agreeing with much of the criticism. Yet as with all other professions, there is much variability in I/OPs, and some of them can be very pragmatic and commercial.

- Psychometricians. As the name suggests, psychometricians typically specialize in the development of psychometric tests. They are often I/OPs but can also be mathematicians. As a group, they probably have a deeper understanding of the technicalities of measurement than anyone else. Yet few have business experience, and fewer still have the ability to explain complex technicalities in simple terms that business users can understand. As a result, the consultancies employing them often keep them away from clients, and they are rarely employed by businesses directly. However, if you can find a good psychometrician with an appreciation of the realities of operating within a corporate environment and the ability to explain the mathematical complexities of measurement in easily understandable terms, then you have found the holy grail of measurement expertise.

- Consultants. Like psychometricians, consultants are often I/OPs. Other types of psychologists, such as educational, forensic, and counseling psychologists, are common. Some vendors also employ nonpsychologists who are trained in measurement methods. We know of one large global vendor, for example, that advocates the qualities of former priests. Another employs mainly ex-businesspeople. These varied backgrounds mean that consultants can lack some of the technical knowledge that I/OPs bring, yet they can make up for this with their experience of implementing measurement processes.

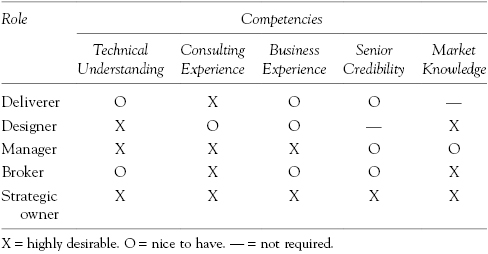

Understanding the differences among these groups can be useful, but when trying to select individuals to employ, it can be more useful to think in terms of competencies. We typically identify five:

- Technical knowledge

- Consulting experience in delivering and implementing a variety of measurement processes in a range of businesses

- Pragmatism and commerciality (commercial experience—the ability to operate effectively within organizations)

- Credibility at senior levels of a business

- Market knowledge

Using these qualities, we can identify the type of individual needed to fulfill each of the five key measurement roles described above (see table 8.1).

Table 8.1 Competency Requirements of the Five Core Measurement Roles

Finding the Right Mix

As with any other role, it is important to find people with the right mix of experience and abilities. The most common challenge here is obtaining people who have both technical expertise and business experience. The crux of this issue is often seen to be the apparent gap that exists between the scientific I/OP world and the commercial, pragmatic business world. Fairly or unfairly, firms tend to view I/OPs as being more focused on making measures that are as good as possible at measuring than on making ones that help businesses work better. The I/OP training institutions show little inclination to change their approach, however. And why should they? They would argue that their job is to produce professionals who know about I/OP, not to produce people for businesses. Since the issue is unlikely to be resolved anytime soon, businesses need to find their own solutions.

One obvious option is to employ junior-level I/OPs and then promote them, gradually teaching them how to operate in a business just like anyone else. But since few firms have large I/OP teams that give room for progression, this is not usually a viable option. An alternative is to employ “second-jobbers”: I/OPs who have obtained some initial business experience in other organizations. Yet this option, while more viable for many businesses, is limited by the relatively small size of the I/OP job market.

Finally, there is the option of employing consultants in-house. The idea is that they may not have experience of operating in business, but they do have experience of operating in partnership with companies and tend to be fairly pragmatic. However, they can be difficult to attract, and the transition for consultants is not always easy, since the qualities needed to succeed in corporate environments tend to be different from those required in consultancies.

Because finding the right people is not always easy, many firms effectively outsource measurement. It is not an ideal solution because there are some things that external vendors cannot do. Evaluating their own work, for one, cannot—or at least should not—be left to them. They also cannot manage results and link them with a company's other talent data. Moreover, although many aspects of measurement can be outsourced, there are still the issues of how to choose and work most effectively with vendors. And when a firm has no other access to measurement expertise, doing this well can be difficult. Yet there are things you can do.

Using Vendors

The vast majority of businesses that we have worked with rely at least to some degree on external providers. In fact, studies show that measurement is among the most frequently outsourced of all HR activities. There is nothing wrong with this: it can be an effective strategy. The big but here is that outsourcing is effective only when businesses know how to select, contract, and manage measurement vendors.

In the rest of this chapter, we present some simple guidelines on how to do each of these three things. Before we do so, though, let us briefly look at the state of the market today.

The State of the Market

The sheer number of vendors is staggering. The choice seems endless. Historically, however, they have divided into two clear groups. On the one side, there have been specialist psychometric and 360-degree feedback vendors, which primarily create and sell tests and tools. On the other side have been the general measurement consultancies, which do things like run assessment centers and provide individual psychological assessments, but get involved in almost everything related to measuring and developing talent (see table 8.2).

Table 8.2 Examples of the Two Groups of Vendors

| Specialist Vendors | Generalist Vendors |

|---|---|

| SHL (previously known as Saville & Holdsworth, now US owned) | DDI (US-based, global, privately owned firm) |

| OPP (which operates in the United States in partnership with CPP and ipat) | PDI (US based and global) |

| Saville Consulting (formed by one of the founders of SHL) | YSC (UK based and global) |

| TalentQ (formed by the other founder of SHL) | Cubiks (Europe based and global) |

The line between these two camps has always been blurred (Cubiks, for example, specializes in psychometrics and 360-degree feedback systems). But the downturn that began in 2007 has seen the line become ever less distinct.

Many measurement firms have fared well during the downturn, fueled by business restructurings and increased caution in hiring decisions. Not everyone has done well, of course. The general consultancies seemed to have fared better than the specialist psychometric and 360-degree feedback vendors. And because of the sensitive nature of restructuring, businesses have tended to use trusted big-name vendors, leaving many of the smaller firms struggling. There has thus been some consolidation within the industry, with a gradual trend for larger firms to buy smaller providers.

However, the market space was radically changed by new entrants in 2011 and 2012. In 2011, two of the biggest specialist psychometric vendors, SHL and Previsor, merged in a long-predicted deal. Then, in mid-2012, a company previously unknown in the measurement space, the Corporate Executive Board, bought both the now giant SHL-Previsor and a respected US general measurement firm called Valtera.

At the same time, search firms have been developing their measurement businesses in an effort to diversify their income. Korn/Ferry, in particular, has gone on a buying spree, acquiring personnel and a number of smaller businesses, before acquiring the once market leader in assessment, PDI. Other search firms such as Heidrick & Struggles and Egon Zender have followed suit, though they appear more focused on the organic growth of their existing measurement businesses. The expansion of these firms has not just been about size: their products and services have expanded as well. Traditionally they operated at an entirely different price point to the specialist assessment and development consultancies, charging two to three times as much. Some still do this, too, although there is no evidence that we are aware of that these higher costs equate to better predictive validities. Many of them, however, launched new services and products priced to compete directly with the mainstream measurement market. Whether they will be successful remains to be seen. For example, we know of many HR people who strongly believe that headhunting firms should not be let anywhere near their talent and that measurement and search should be kept independent. Search firms would argue that their assessment businesses are separate from their headhunting arms. Yet we suspect that the reservations of many HR professionals will remain and thereby limit headhunters' role in the market. Nonetheless, they are players and have a growing chunk of the market.

Finally, hovering on the edge of this picture are two groups. First, there are the persistent rumors that some of the big business consultancies might try to move into the measurement market through a large acquisition. Second, there are the twin peaks of IBM and Oracle. In 2012 each completed a high-profile purchase of a company combining a talent acquisition system (for managing recruitment processes) with measurement products (IBM purchased Kenexa, and Oracle bought Taleo). Many specialist psychometric providers are keeping a careful eye on these developments, and some appear to be diversifying into the general measurement consultancy space as a contingency.

So there has been a lot of movement in the market, and there is likely to be more. The general thrust seems to be that many medium-sized firms have been bought or squeezed out, leaving a mix of larger consultancies and quite small ones. These smaller firms are generally too small for their bigger counterparts to worry about, but their lower cost base means that they can be attractive to organizations.

The current round of consolidation is undoubtedly overdue and promises to cohere what has historically been a fragmented market. It is something we welcome and see as good news for organizations, making it easier for them to navigate the market and choose which product and vendor to use. Yet as independent observers of the field, we also view the current round of consolidations with some concern, as there is a noticeable trend among many of the new entrants to the market to monetize the intellectual capital of measurement firms through promoting generic and global products.

This approach can certainly make choosing assessment products easier for companies. But the problem with this approach, as we showed in chapter 3, is that the more generic measures are, the less likely they are to achieve high validities and help businesses measure fit. Our concern therefore is that the intervention of new players without a long tradition in what is a very specialist technical arena will bring with it a raft of generic, off-the-shelf monetized products and services that look good but are not that effective.

How to Select Vendors

How, then, should businesses choose a vendor? The subject is worthy of a book in its own right, and the criteria used vary by businesses and products. Yet a couple of general principles are worth noting.

Conduct a Proper Selection Process.

One of the most common mistakes companies make when selecting vendors is not following a proper process. Lacking technical understanding and faced with an overwhelming number of options, many HR and business leaders have a favorite vendor or tool that they seek to use whenever possible. The selection process can thus become a cover for selecting a preordained favorite. This is bad business in any procurement process, and no less so for measurement. Without genuine competition among vendors, the likelihood of achieving high-quality, cost-effective solutions is distinctly reduced. So follow a proper process. The precontest favorite may well still win, but the competition will put the true value of its bid in perspective.

Select a Measure, Not a Vendor.

A related issue is that because they lack expertise in the field, some businesses simply choose the vendor with which they feel they have the best chemistry. From a business's point of view, it is not entirely a bad idea. One of our core rules is to ask ourselves whether, if things go horribly wrong, we would trust a vendor to stand beside us and deal with the problem. This kind of trust or chemistry factor is a valid selection criterion, but it must not be the only or main one. Organizations must also investigate the quality of the products or services they are purchasing. This is partly about making sure that what they buy measures precisely what it is intended to. Chapters 2 to 4 should help in determining this. It is also partly about questioning the validity of measures. This is especially important given the increasing evidence of reporting bias: the tendency for some vendors, while presenting validities as scientific, to report these figures selectively in a way that overstates the effectiveness of their tools. The guide to questioning validity we presented in chapter 5 can help here. No matter how you do it, though, it is important not to assume that measures are effective or to take vendors' claims at face value. Always question them.

Look for Expertise.

Although we have just said you should focus more on the measure than on the vendor, one critical aspect of vendors is their level of expertise. With individual psychological assessment in particular, it is arguably more important to choose the right assessors than to focus on the measurement process. (For more on how to select an individual psychological assessment vendor, see the appendix.) With smaller vendors, look for people who have come from bigger, more established providers. For example, the founders of the UK-based VesseyHopperMcVeigh all learned their trade at SHL. In larger vendors, individuals' backgrounds are also important, but another useful source of insight can be the origins of the business overall, since mergers and acquisitions can hide who you are really buying from. For instance, IBM's acquisition Kenexa is more known for its talent acquisition systems, but in 2006 Kenexa purchased a reputable psychometrics firm called PSL. And although some people may not have heard of Cubiks (one of the larger global vendors), its origins lie in PA Consulting Group, one of the world's best-known management consultancies.

Reputations and backgrounds are not always what they appear to be, of course. One or two large psychometrics vendors seem to have dined out on their reputation for quite a time now, even though their tests have since been overtaken by newer, better tools. Yet for businesses that do not have technical expertise and need to acquire it, reputations can be a useful indicator.

Do Not Select Only on the Basis of Price.

At the risk of repeating ourselves, measurement is a precision instrument. Purchasing only on price is like buying a supercar on the cheap and still expecting it to be super. There is a degree to which the cost simply is what the cost is. For example, we have seen many organizations seek to drive down the cost of individual psychological assessments, only for vendors to respond by putting less experienced, cheaper consultants in place. You get what you pay for. This does not mean that price is not important. Businesses obviously need to secure the most cost-effective solution possible. But those that select only on the basis of price invariably are stung on quality.

How to Contract with Vendors

Some companies place a strong focus on selecting vendors and then seem to view contracting as a formality. But often it is not. And if they get it wrong, the relationship with the vendor will rarely go right. Larger companies have a legal or procurement department to help with this. Indeed, for these businesses, we recommend simplifying matters by using a standard contract with all measurement vendors. Smaller firms, though, usually have to rely on the contracts presented by vendors. Whichever route is used, there are a number of key issues to bear in mind to avoid the most common pitfalls in contracting with suppliers.

To some, what we write below may sound a little harsh. Yet this is not our intention and, indeed, we firmly believe that contracts must be fair to all parties. We are just trying to be clear, and if contracts do nothing else, they should make things clear.

Intellectual Property Rights.

A number of years ago, one of the best-known global measurement vendors signed a contract with one of the world's largest oil and gas suppliers to produce a new leadership framework for them. Unfortunately the energy firm either did not check the details of the contract or did not understand what they meant: the contract assigned the intellectual property rights (IPR) in the framework to the vendor and prevented the business from using the framework with any other vendors. As a result, the firm was effectively tied to using that vendor for all measurement activity at leadership levels. The only way it can stop using the vendor is to create a new leadership framework.

Intellectual property rights are vital, and some of the biggest vendors are some of the worst culprits here. There are two simple guiding rules. First, if a business pays for the design of a new measure that is not based on something in which the vendor already owns the IPR, then the IPR for the new measure should belong to the business. No debate, no exceptions. If a business pays for the development of a new 360-degree feedback tool or situational judgment tests, then the questions that the tool comprises should belong to the business. The IT system that the tool is delivered on still belongs to the vendor, but the questions should belong to the business. By all means, share the IPR for the questions with the vendor, but do not merely give them to it. There should be no ties that bind. If a vendor does not do its job well, firms should be free to walk away. Moreover, if a vendor develops a tool for you at your expense, do you really want it using some of that content with one of your competitors?

Second, businesses should retain IPR over all data and results but share this unconditionally with the vendor. So if a firm pays to use a psychometric test, it should have the IPR over all the results and reports produced. However, since vendors use these data to produce norm groups and studies, organizations need to share the intellectual property with vendors. This is often done by granting a “perpetual, royalty-free license to use data in an anonymous form for the purpose of norm generation and research.” The principle is that both parties should be free to use the data for their respective purposes. Sometimes vendors do not want to provide data to a business, for example, when an assessment has been part of a developmental process. But in our view, as long as the data are kept securely within the business's central measurement team and confidentiality is maintained, if the business has paid for the data, it should be able to use it.

Intellectual property, then, is an important issue. At stake is a company's freedom to choose to work with another vendor or walk away if a vendor does not do a good job. This freedom is so fundamental that we have one overarching piece of advice: if a vendor insists on retaining IPR over something new that you pay it to design or if it is unwilling to share IPR on data with you, find another vendor that will. No debate, no exceptions.

Total Price.

In principle, this ought to be easier than the intellectual property issue, but it is not always. Businesses need to be clear not only on the upfront costs of using a measure but also on the total costs across the lifetime of a contract. Obviously, at the beginning, it is often not certain how much a measure will be used. But the extra add-on costs that can emerge need to be specified in advance. For example, project management fees increasingly seem to be viewed as an add-on. We experienced one vendor showing these costs in a brief comment in small print at the bottom of its proposal: “A 14 percent project management fee will be added to all costs.” It claimed that it had separated out the cost to make the charges easier to understand, but we were not convinced by this, and indeed remain unconvinced.

Other common add-on costs are things like training end users to use reports (which some vendors may insist on) and training staff to use test administration systems (which may be necessary). With psychometrics, be aware of any test development that may be required, such as additional translations or the development of norm groups specific to your business. Finally, some vendors charge extra for attending annual or quarterly review meetings, although we recommend that you do not accept any such charges.

The key here is to be aware of potential additional costs and that some vendors are more forthcoming and clearer in presenting them than others.

Travel Claims.

This is not usually a contentious issue, but it is one to be aware of. The idea here is that vendors should not charge for the time it takes them to travel to and from any location to complete work for a business if that travel lasts less than a certain number of hours (door-to-door). There are regional variations in what this number is, but it is usually between two and four hours. When travel takes longer than this, the total time spent traveling is typically charged at 50 percent of consultants' normal day rate.

Targets, Performance Indicators, and Penalty Clauses.

All contracts should lay out clear targets, performance indicators, and penalties. Organizations that do this well tend to report higher levels of vendor performance and lower levels of opportunistic behavior from vendors. The bit that is often missed is the penalty clauses. Yet they are essential, since they set the boundaries of acceptable performance. Bear in mind, though, that this is a two-way street. Vendors may well want to place penalty clauses of their own, and for the most part, we support this. Contracts, after all, need to be fair to all parties.

Termination Clauses.

Last, but by no means least, there should be no penalty if a business terminates a contract. Sometimes a vendor offers a reduced setup or design fee to attract businesses, but it compensates for this by applying higher fees per assessment or by assuming that it will receive a certain amount of business. In these situations, it might want a termination clause that ties businesses in for a certain period and thus gives the vendor a chance to recoup its setup costs. In our experience, it is better to pay a higher setup fee and be free to walk away if thing go wrong than to choose lower setup costs at the expense of being tied to a vendor.

How to Manage Vendors

When it comes to managing measurement vendors, all of the usual guidelines apply, including being clear about expectations and communicating openly. Make sure, then, that there are regular review meetings and, where possible, foster a spirit of partnership. Nevertheless, there are a number of issues that are particularly relevant for measurement vendors.

Onboard Vendors.

Without an onboarding plan, it can be difficult to ensure that vendors have the necessary level of understanding about the business and its culture to develop and deliver effective solutions. With methods such as assessment centers and individual psychological assessment, for example, assessors need to understand the business if they are to make accurate judgments about individuals' level of fit with it.

If you are using these methods, it is important to arrange an induction to the business for the vendor's team of assessors. The introduction should familiarize them with the company's strategy and culture and advise on the types of people who tend to do well in the business: that is, those who tend to fit in well with the culture, perform well, and be promoted. It is also important to arrange a conversation between the assessor and the manager or hiring manager of an individual being assessed. The manager can then advise on the challenges the individual will face in the role and the stakeholders he or she will have to work and interact with.

Obviously, with measures such as psychometrics, these steps are not so relevant. Yet for processes in which an assessor is making judgments, they can be critical. So we are continually surprised by the lack of attention paid to them. Many businesses seem to assume that vendors have business knowledge and therefore skip this step. Yet by doing so, they risk limiting the effectiveness of any measures, since without these briefings, assessors cannot accurately measure fit.

Evaluate Vendors.

In early 2011, the Romanian parliament sat down to discuss a controversial new law: that Romanian witches and fortune-tellers making predictions about the future should be penalized if their predictions did not come true. At the risk of being cursed, we think this is a good idea, and not just for witches. Measurement vendors are effectively making predictions about the future—about who is likely to succeed and who is not. Yet businesses all too often purchase measures without subsequently checking if the measures genuinely are predictive. Indeed, we never cease to be amazed by the number of firms that speak highly of their vendors but have no hard, internally produced data to back this up. Since firms invariably go on to purchase more measures, this is extraordinarily bad business.

This is why in chapter 6 we described the need to evaluate the impact of measures as one of the four foundations of making measurement work. And as we noted there, this is more than about simply checking whether measures work after the fact. Measuring effectiveness is a key element of tailoring tools to businesses' specific needs, and if this not done, organizations are limiting the effectiveness of measures.

Leverage Market Forces in Managing Suppliers.

Larger organizations often use multiple vendors, yet few have an active plan to leverage the market forces that can be created by having more than one vendor. This is a lost opportunity, since research shows that the market forces created by competition between vendors can result in improved service levels and reduced costs.1 There are three things in particular that businesses can do here: do not let the vendor pool grow too large, measure vendors' performance, and make these performance data widely available.

For example, when setting up an individual psychological assessment process for new senior-level staff across a large multinational energy firm, we realized that the sheer number of locations meant that we were going to need more than one vendor. We therefore launched what we called a guided calibrated market. We selected three vendors and agreed on a common format for the IPAs, a common process for scheduling them, and common, standardized reports. We also used standardized contracts to ensure that the terms and conditions were the same for each vendor. The only element that differed between them was the price. We then gave the various business units the choice of which of the three vendors to select. We brought the vendors together regularly to calibrate judgments and tracked their rating tendencies statistically. We also measured their performance along a number of dimensions and made this information available to the business units on an ongoing basis. Finally, at the end of every year, we evaluated whether to retain the vendors or replace some or all of them. The business loved having the choice, and we are certain that we achieved a better-quality process and lower costs by adopting this approach.

Beware Closed Systems.

One way organizations seek to control the quality of vendors across diverse business units is to use preferred supplier lists. Although these lists have their benefits, it is critical to have a mechanism for promoting new suppliers onto the list and removing existing suppliers from it. Without such a mechanism, businesses' ability to apply market pressures to vendors will be limited.

Invest in Vendor Management Skills

Research shows that effective vendor management is the single most significant factor within a company's control for ensuring successful outcomes with vendors.2 Yet many companies appear to assume that employees already have these skills. Do not make this assumption. Given the large amounts that some businesses spend with vendors, investing in vendor management skills is vital.

On Track for Successful Implementation

In the previous three chapters, we looked at the challenges and opportunities in implementing measurement. We laid out four clear foundations for making measurement work and ensure that it has the impact it should. We looked at how to make the most of results and turn all the talent data produced into talent intelligence, capable of doing more than merely informing individual people decisions. And now, in this chapter, we have looked at how to source the expertise needed to do all this. We have considered how to select, contract with, and manage vendors and how firms that employ internal experts can make sure they have the right kind of expertise in the right places to make a real difference.

Implementation has long been the forgotten side of measurement. All the headlines seem to have gone to the selection of products and vendors. And when implementation has been considered, it has tended to be in terms of the project management or communications involved. These are important, and we do not want to downplay them. But measurement is not the same as any other business process. It has quirks and idiosyncrasies that require special attention, and if you ignore them, you risk undermining the effectiveness and value of measures.

More than anything else, it was this neglected side of measurement that drove us to write this book. If you take nothing else away, we hope you will have acquired increased awareness of these implementation issues, a sense that you now know what to do about them, and a belief that you can do it.

Notes

1. Klaas, B. S., McClendon, J., & Gainey, T. W. (1999). HR outsourcing and its impact: The role of transaction costs. Personnel Psychology, 52(1), 113–136.

2. Enlow, S., & Ertel, D. (2006). Achieving outsourcing success: Effective relationship management. Compensation and Benefits Review, 38, 50–55.