6

Building the Foundations for Talent Measurement

For some readers, the suggestion of a chapter dealing with foundations, infrastructure, and—dare we even say it—policy may sound dreadfully dull. But as we hope that we will show it is anything but dull. Indeed, getting these issues right is possibly the single biggest opportunity that firms have to maximize the impact and value of talent measurement. This is because what these issues tend to affect most is what you can do with the outputs and results of measurement. And even the best tools are only as valuable as what you can do with the results. Consequently, these seemingly fringe tasks are in fact a critical part of the measurement process. Not done right, they are one of the main reasons talent measurement can fail to have the impact it should. Done well, they are the key to turning talent data into genuine talent intelligence.

In this chapter, then, we explore the foundations that talent measurement needs to be built on in order to be effective—the elements that need to be in place around it for measurement to have the impact it should. We look first at four essential foundations that you absolutely must have in place: central data collection, common data points, a check on whether measures work, and processes to ensure proper use. We then look at the strategic and policy issues that you need to be aware of and consider but may not always have to act on. And finally, we introduce one further foundation—the measurement of different types of performance—that has the potential to radically improve the quality of measures and tools available to organizations.

There are some easy wins here too—some low-hanging fruit that every organization using measurement can take advantage of. The challenge is mostly just knowing what they are.

Why Foundations Are Often Missing

Many of the foundations for measurement we discuss in this chapter may sound obvious, yet they are often overlooked. This is partly because they are less visible than the more upfront challenges of choosing which measure to use. It is also because they require some strategic planning, something that the use of measurement processes does not often include.

In most companies, measurement use is usually driven by practical operational issues as they arise. A small business may elect to use measurement in one particular recruitment process, or a particular business unit within a larger organization may decide it wants to assess people as part of a change project. Either way, talent measurement often has small beginnings and then spreads from there.

This demand-driven approach is certainly practical, but it tends to leave broader issues largely unaddressed. As a result, the foundations required for effective measurement are often not in place. A classic sign of this is when the implementation of talent measurement varies considerably in different parts of a business. Unfortunately, in our work with organizations, we have found that an ad hoc approach is the norm in most businesses, and there are several major risks associated with it:

- Measurement processes are more likely to vary in quality, reducing their impact on the business.

- Measurement outputs (the results) may be employed in ways that limit their value. Assessment reports, for example, may not be used properly or may not be linked to other processes such as onboarding or training.

- There may be no central collection of results. This prevents firms from pooling and comparing data from different processes or parts of the organization.

- Different competency frameworks may be used. Again, this can prevent data from being pooled and can limit the degree to which businesses can build benchmarks.

- Policies regarding digital security and data protection, for example, may vary or be missing. This can create regulatory compliance and litigation risks.

- Assessment vendors tend to be managed locally, resulting in mixed quality and missed financial opportunities for economies of scale.

- There is likely to be no central oversight of the total spending on measurement. In one business we worked with, for instance, we found that the business units were spending over $25 million between them. Yet because of the siloed nature of the firm, it had no idea that it was spending this much overall.

Thus, even organizations that make limited use of talent measurement need to be aware of the broader foundational challenges because they cannot be overcome by leaving them to chance. Foundations need to be designed, and the earlier they are in place, the sooner organizations can start making sure that measurement processes have the impact that they should.

So what are these issues? To help us think about this, we like to distinguish between two kinds of foundational issues: the things that organizations absolutely must do to guarantee impact and value from talent measurement and the things that they need to be aware of and think about but do not necessarily need to act on. We look at each of these in turn.

Four Things You Must Do to Make Measurement Work

Every company must put four core foundations in place to make measurement work:

- Collect data centrally.

- Use common data points.

- Check the impact of measures.

- Ensure proper use.

Collect Data Centrally

The first building block for effective measurement is to collect data centrally. All assessment results should be gathered in one place. Interview ratings, psychometric scores, competency ratings: all need to be collated from throughout the business. Wherever measurement data exist, they need to be drawn in. It may be possible to use an HR information technology system to store the data, but at the very least, there needs to be a large, central spreadsheet containing all results and a secure place to keep all reports. The centrality of the database is critical too, so that the data can be shared. In businesses with both recruitment and learning teams, for example, it should sit outside both so it is not viewed as belonging to one, but not the other.

Without centrally collecting talent data, businesses cannot build up a picture of the talent across the organization. Instead, all they will have are fragments of information relating only to individuals or teams. Not collecting measurement data is like buying a sports car and then leaving it on the driveway or using it only to drive the kids to school. You will only ever enjoy a small margin of the value that the car can provide.

Even when firms do not use measurement methods much, they should still collect the data so that they can follow trends over time. In some firms, for example, measurement is limited to recruitment interviews, and the only outputs are a whether-to-hire rating and perhaps competency ratings. These may not seem like much, but they can be extremely useful and ought to be collected. Data are only as useful as the insights they give, and the insights they give are vastly increased when they are connected with other data.

For example, knowing the average competency ratings of newly hired employees can be useful. Yet if you also know the performance scores of the newly hired one year after they have joined the business, you can see which competencies are most predictive of initial success. If you know who is still employed three years later, you can work out which factors are most predictive of retention. And knowing who is later promoted can provide insight into the types of talent valued in your business and the qualities predictive of longer-term success.

Moreover, because companies need not only to gather talent data, but also to join those data with other information, they should never be tempted to let a vendor take care of data collection for them. Businesses must own and control their measurement data, because only they can connect these results to other talent data. Right from the start, they need to record other relevant talent data alongside the measurement results—things like performance scores, promotion dates, business unit, location, and key demographic data. And it is critical to do this from the very beginning because the fragmented nature of many larger companies' systems and processes can make gathering this information extremely challenging in retrospect.

We look in more detail at what organizations can do with measurement data in the next chapter. For now, the key point is that if measurement results are to be useful for more than merely informing individual people decisions, data need to be collected centrally. They are valuable resources and should be managed as such.

Use Common Data Points

Just collecting talent measurement data centrally is not enough, however. For this information to be meaningful and useful, you need to have common data points. For example, if you measure one person's intelligence and another's personality, bringing the two pieces of information together will not tell you much. But if you know the personalities of both people, then you can compare them. And if you know this for enough people, you can compare individuals to the average profiles of a group or the qualities of different groups, such as the leadership teams of different business units. It is therefore critical that as far as possible, you know the same information about different employees. Without this, any measurement database will be of little value in what it can tell you, and talent analytics will simply not be possible.

One significant step in this direction can be to ensure that if you use intelligence or personality tests in your business, you use the same tests and not different ones from different vendors. This is important because comparing the scores from two different tests can be very difficult and is often impossible. Using the same tests is not always easy to achieve, though, since business or HR leaders often have their own favorite tools. And for large multinationals, it may not be completely possible: they may find, for instance, that the intelligence test that most suits the majority of the business is not available in some locations. Yet as far as possible, the guiding principle ought to be that the tools and tests you use should be standardized.

In many businesses, the main tools used to measure talent are competency frameworks. These describe the skills, behaviors, and attributes that individuals are thought to need to be successful. They can exist for single job families, but can also be used to define the capabilities required in particular groups of people across whole business units or organizations. For example, many businesses have a set of leadership competencies that are used for all of their senior leaders or technical competencies specific to particular functions. As a result, competency frameworks provide an excellent opportunity for ensuring there are common data points.

There is a tension here, however. On the one hand, the fewer frameworks your business has, the more able it will be to collate and compare competency ratings from different parts of the business. Yet on the other hand, as we saw in chapter 3, when assessments take into account the specific circumstances and needs of a business unit or team, then those assessments are likely to be more accurate in predicting individuals' success in those environments. So the more specific and personal that a competency framework is to your company or business unit, the more effective it is likely to be for measuring talent. And if we follow this line of reasoning, then larger businesses may well be better off with lots of different frameworks, each specific to a particular part of the organization.

So although a single common framework is probably appropriate for small firms, a compromise is required for large or diversified businesses. They need both business-specific frameworks that enable an accurate evaluation of the fit between individuals and business needs and common data points in order to be able to use the measurement data for more than just informing individual people decisions.

The solution here is compromise. The guiding principle should always be to have as few frameworks as possible, so that there are some common data points between people of different levels and in different parts of the business. Yet this still leaves room for competencies specific to particular populations. One approach that we have seen work well is to have both generic and business unit–specific behavioral competencies, in addition to technical ones. This allows both common data points and tailored, business-specific assessments. For example, a company could have a framework that consists of:

- Technical competencies specific to particular functions or job families. In small firms, this could be a single competency called “technical knowledge.” In organizations with significantly sized functions, there could be a collection of competencies for each technical area.

- Two or three behavioral competencies specific to each of its business units that describe what is required to succeed in each area.

- Three or four generic behavioral competencies against which everyone is evaluated. If some abilities are specific to the leadership populations, then an additional one or two can be added for this group.

As an example of this approach, consider a large, global energy firm we worked with. It had a competency framework that it used across the whole firm to collect common data points. One business unit, though, decided to supplement this with three additional competencies. It believed that these more accurately described the necessary qualities to succeed in its particular business area. Two years later, it was proved correct. The three unit-specific competencies more accurately predicted performance than the wider firm's generic framework.1

One final point to note here is that not just any competencies will do: they need to be suitable for measurement (and not all of them are). Developing effective competency frameworks is a subject worthy of a book in its own right. Because our focus here is the need for common data points rather than competencies, we will not dwell further on their construction at this time. However, in the appendix at the back of this book, we address the issue of how you can tell whether a framework is suitable for measuring talent.

Collecting common data points is thus an essential foundation for obtaining meaningful data. Like collecting data centrally, it is an absolute must for organizations hoping to build up a picture of the talent across the business.

Check the Impact of Measures

The third must-do action for businesses in making measurement effective is to check whether the methods and tools they use work. All too often, companies see that a tool has a certain validity and then seem to take it for granted that it will have the desired impact. In this respect, when it comes to measurement, organizations appear to be running on faith. A recent survey showed that 79 percent believe that measurement adds value to their organization, but only 23 percent actually check that it does.2

Why is checking impact so important? One obvious reason is that spending money on a service without having any idea if it works is plainly bad business. A less obvious one is that measurement methods are not like most other products that you buy. Despite what some vendors may try to tell you, most of the time most tools do not reach you as finished products. If you are using psychometric tests with a limited number of people, then there is little, if any, finishing to do, and using them straight off the shelf is fine. But most methods require some extra tuning, especially if you are going to be using them a lot (for example, with over one hundred people). Norm groups need to be built, exercises adjusted, and tools tailored to measure fit with a particular organization, business unit, or role. None of this can happen without some feedback about whether the measure is in fact working.

We live in a world where most of the products and services we buy and use work perfectly the first time. We expect this, even demand it. But talent measures are precision instruments, and they require optimizing. You should not expect them to work perfectly straightaway. Indeed, when you first check their efficacy, you should expect to find room for improvement.

Nancy Tippins, a past president of the American Psychological Association's organizational psychology division, has spoken passionately about this. As she puts it, “Businesses often buy a measurement product and then do not do anything else with it. They expect it to work straight out of the box. To get the most from these products, though, they need to continually hone and optimize them.”3 Evaluating impact is important not only for checking if measures work, but also for making them work.

Some companies require vendors to check these issues for them. But no matter how positive your relationship with a vendor is, asking it to evaluate its own tools is not advisable. There is just too much vested interest. By all means, ask a vendor to help share the work involved, but you must own and lead your own process.

Moreover, we are not simply talking about checking and honing the efficacy of a vendor's products. Evaluating impact is also vital to help managers improve their people decisions. For example, one business we work with always follows up the “failure” of new employees with a review meeting involving the hiring manager or recruitment lead. The meeting usually lasts no more than thirty minutes. During it, the information available at the time of hiring is reviewed to see if any potential signs of failure were missed. The idea is not to lay blame, but to have a genuinely curious inquiry with the aim of helping people improve their selection skills.

So how can businesses go about evaluating impact? There are two main ways. There are simple validity studies, which check whether ratings or results predict subsequent performance, and there are impact studies. For promotion decisions, an example of an impact study would be following up to check success rates among those promoted. For recruitment decisions, meanwhile, quality of hire metrics can be used. These include a variety of indicators. The trick is not to track them all, but to select and focus on just a few. Monitoring these indicators need not be complicated, either. In fact if you have the first two foundations in place—centrally collected data and common data points—then it can be quick and easy to check the data regularly. The list of possibilities is long and includes the following:

- Retention figures

- Performance ratings

- Hiring manager's satisfaction with new employees

- New employees' reactions to the measurement process

- New employees' end-of-year bonus allocation

- Comparison of competency ratings at hiring interview and at first annual appraisal

- Whether a new employee is tagged as high potential within an agreed time period

- The number of legal challenges to a selection process

So our third foundation is the need to check whether measures work and their impact on actual people decisions—not as some kind of after-the-fact evaluation but as an integral part of making measurement work.

Ensure Proper Use

The first three foundations are all fairly simple. They do not take significant time or resources. All they really need is a little will. The final foundation can be a bit tougher. It is the need to ensure that the tools and methods of measurement are used properly. You can have the best tests in the world, but if you do not use them properly, they are not going to work as well as they should.

There are two issues here. The first is making sure that tools are used for proper and appropriate purposes. For example, some types of personality psychometrics—called ipsative tests—are suitable only for development processes, not selection (see the appendix). Some types of tools do not work with particular populations. English-language intelligence tests, for instance, should be used only with people for whom English is their mother tongue. And some types of tools should probably never be used, such as Facebook content and credit scores.

The second issue is making sure that the outputs of measurement processes—the ratings, results, and reports—are used properly. For example, you can make sure that managers do not hire only one personality type or that hiring decisions do indeed take measurement results into account. We have seen too many businesses that have put great effort into identifying the best tools to use, only to leave it to line managers to decide how they want to use them. And inevitably this leads to mixed or poor use of the outputs.

These two issues are usually easier for smaller companies than larger ones. In decentralized businesses, they can be particularly challenging. Nonetheless, organizations need to do something, and they have two basic options:

- Mandate particular measurement processes. For example, many firms stipulate that some people decisions, such as hiring above a certain level of seniority, are supported by the use of particular measures. Others insist on involving people who have attended specific training (such as advanced interviewing skills).

- Guide use. Some organizations provide lists of recommended tools and vendors to ensure overall consistency while still allowing business units some flexibility in their choices.

The route businesses choose will depend on their size and culture. What makes ensuring proper use so challenging for some businesses is the fact that it requires consistency. For larger, decentralized, or geographically dispersed organizations, this can be tough. Moreover, it touches on the activity and decisions of individual managers and leaders, which can be quite politically sensitive in some firms. And, of course, the key to being able to ensure proper use is having access to expertise, which many companies do not.

Yet despite the difficulties, businesses need to act to ensure that measurement outputs are used properly and to best effect. We return to this topic in the next chapter. For the moment, though, what is important is to acknowledge that it is a crucial issue and one that must not be ignored.

Two Things You Need to Think About

In addition to these four foundations that organizations absolutely must lay to make measurement work, there are, of course, other issues they need to be aware of and think about. These issues may not be as fundamental, but they are important. Some of them can have a significant impact on the efficacy of measurement. Others are levers that businesses can use to ensure proper use. We like to divide these issues into two camps: strategy and policy.

Strategy

As we have noted, the development of measurement practices in most businesses is not a strategic affair. It is emergent and demand led, and by and large, this is fine. In fact, it is essential that measurement processes serve a real business need.

The closest most businesses get to having a measurement strategy is when they consider one of three main issues: whom to assess, centralization, and standardization. Yet as we will go on to show, there is a fourth issue as well; it is rarely raised but has the potential to be the most strategic one of all.

Whom to Assess.

It is rare for businesses to think about this early on, before they assess anyone. But the question often comes up when they are thinking about expanding a particular measurement process—for example, whether to expand the use of individual psychological assessments from only executives to the wider senior management population.

In our experience, rather than thinking about which groups of people to assess, businesses are better off thinking about the talent issues they want to address. They can then target measurement processes to support these. To deal with the question of whether to expand individual psychological assessment to senior leaders, then, we would check the quality and success rates of recently hired senior management. If all looks good, there may be no imperative to expand the use of these assessments.

- When a large volume of candidates needs to be sifted

- When significant cost is associated with selection failure—for example, where there is a high risk of accidents or in senior executive assessment

- When there is a significant need for perceived fairness or objectivity—for instance, during a restructuring or in countries with heavy regulatory requirements

- When input is required on where best to target learning and development—for example, when deciding which people to offer training to or when trying to identify what specific individuals' development needs are

Centralization and Standardization.

These second and third strategy issues are often seen as the same, but in fact whether to centralize and whether to standardize measurement processes across the business are separate questions. Centralization is mainly about positioning in the business. It is about reporting lines and whether decision-making authority lies at the center of the business or within individual business units. Standardization, by contrast, is about aligning processes. We mentioned earlier, for example, that some organizations use the same tools or vendors across their business to help ensure common data points. So you can have centralization without aligning any processes and you can have standardization without having decision-making authority.

Companies often try to pursue centralization and standardization because of the benefits they can bring. These include reduced costs through economies of scale, minimized duplication of effort, and better quality control. Indeed, they are the key mechanisms that firms have to ensure the proper use of tools. Yet they come at a cost. Most notable, they involve a trade-off with being able to adapt to and support the unique needs of different business units.

This is true for any process, but talent measurement has an added dimension because fully standardized measurement processes are not possible in global businesses due to the different legal and cultural contexts. What you are allowed to do with data can vary among countries. Measures often have to be adapted to local use, and locally developed measures may need to be used in some cases. The question is not so much whether to centralize or standardize, but what to centralize or standardize and what not to.

We have already mentioned the need to centralize data collection and standardize certain data points. There are other options too. The most common way to centralize measurement is through structure and reporting lines, with a central point of expertise or oversight for measurement. Another common option is to have a centrally set preferred supplier list. We explore both of these options in more detail in chapter 8.

Organizations also often centralize through funding. For example, the cost of measurement processes can be paid by each business unit or can come out of a central budget. The advantage of local payment is that leaders are more likely to value something that they pay for themselves. The advantage of central payment is that it can be a better way to ensure that leaders do use a measurement process. There is no one right way of doing this, and the broader business culture and structure will usually determine which is pursued.

As for standardization, this commonly involves ensuring that similar products and processes are used across the business. Companies are also increasingly adapting the outputs of different tools so they all look similar, even though they may come from different vendors. This can help ensure that methods and tools feel familiar to managers and do not require extra training. Finally, standardization also includes ensuring that outputs are used consistently, a topic we look at in more detail in the next chapter.

A Fourth Strategic Conversation.

This issue is not often raised, but it is the most strategic of the lot. It is how to use measurement to identify, support, and solve the talent issues that businesses face.

In our experience, businesses tend to use measurement processes to support individual decisions, but do not think further than this. We came across a business, for example, that had been using formal measurement methods for five years. In that time, it had assessed thousands of people. And it had done almost everything right: it had collected data centrally, used common data points, worked to ensure proper use, and had even evaluated the impact of measures.

Yet what it had not done was to think about what it wanted to use measurement for beyond merely supporting individual people decisions. It had not considered how it might use the data it collected to gain insight into the flow of talent through the business. As a result, when harder times came and budgets were cut, the measurement was stopped. It was seen as high quality but not high value. It was not anchored in the real talent issues of the organization, and there was no clearly communicated link between it and business priorities.

To make measurement strategic and extract the maximum value from it, organizations need to think about what they want to use measurement for, above and beyond just measuring people. And in our experience, this conversation does not happen often enough.

Policy

As words go, policy hardly instills excitement. It certainly lacks the appeal of its sexier sibling, strategy, but it is no less important for that. Done well, creating policy is about giving simple, succinct, and clear guidance about what to do in certain situations.

We should state now that we believe policy should be kept to a minimum, and we are not fans of long policy documents. Thick manuals that lie unread are of little use. Brief, specific statements of principle, however, can be useful. At the very least, you need to be aware of some of these issues and know your position on them.

We tend to distinguish between two types of policy: those that emerge, developing out of issues as you first encounter them, and those that it is best to think through before any issues emerge. Emerging policies can be things like whether to retest people who report problems completing online ability tests or how to respond to some disability matters, such as using intelligence tests with people who are dyslexic. With these issues, the vendor is usually best placed to advise on how to respond. Companies do not need to have a stance on them beforehand, but they do need to learn from them when they do occur.

The policy issues that should be thought through before using measurement mostly concern data privacy and protection—in other words, who has access to individuals' measurement results and how these results are kept secure. The laws of the countries in which firms operate determine what they have to do here. One thing worth noting, though, is that there are some big national differences.

For instance, the United States may be far stricter about adverse impact than other countries (see chapter 5), but the European Union (EU) is far stricter about data privacy. Specifically, the 1995 Directive on Data Protection by the European Commission states that personal data may be transferred to other countries only if the countries provide adequate data protection. And according to the EU, the United States does not, so a US business with a European office or using an EU-based vendor could be restricted from sending data from the EU to the United States. Fortunately, there are some easy solutions that vendors can use, but you need to be aware of the regulations and comply with them.

Even companies that operate only in one location need to think about data privacy. For example, they need to consider how they will store data and keep them secure (larger firms may have a digital security department with its own policies on this). They also need to think about who will have access to measurement results. These can be simple decisions, but decisions do need to be made.

Larger companies tend to have a legal department to help them navigate these matters. For smaller firms, the easiest option is often to ask vendors for guidance. Since regulations differ, we cannot offer any definitive advice here, but as general guidance, we always try to follow four simple rules:

- Keep data secure—for example, lock reports in a cabinet, or password-protect a spreadsheet containing results.

- Give access to as few people as possible.

- Keep only the data you need.

- Keep data only as long as you need them. Where possible, make them anonymous.

One final factor you should think through before embarking on measurement processes is whether to provide feedback about measurement results to participants. When the measurement is part of a development process, the answer will almost always be yes. But with recruitment processes, it is not always so easy. Some companies see it as an ethical obligation. Others avoid it for fear of the risk of litigation. Some provide information only to successful candidates. Some do different things at different levels. And the feedback given can involve anything from a simple pass-or-fail statement to a detailed report and coaching session.

Factors influencing your decision will be the litigation environment of where you are operating and issues such as the number and level of candidates. There is no correct answer here, but our general advice is to give some level of feedback wherever possible. If nothing else, research has shown that when done sensitively, it can improve candidates' perceptions of the selection process and thus the reputation of the company.4 Furthermore, whatever level of feedback is given, candidates should always be advised beforehand what to expect.

The Final Foundation: Linking Measurement to Performance

So far, we have looked at four fundamental foundations that must be laid for talent measurement to work and briefly explored the strategy and policy issues that businesses need to consider when using measurement. There is one final foundational issue that we need to look at. This foundation is not strictly absolutely necessary for measurement to work or a matter of strategy or policy. But put in place, it can significantly improve the quality of measures and tools available to organizations and thereby also improve the decisions they make about people.

As we mentioned in chapter 3, one of the curious things about talent measurement is that generally, the past thirty years have not seen the development of measures that are substantially more predictive. Ask vendors why and what their biggest challenges are in developing and improving assessments, and their response is usually the same: a shake of the head, a deep sigh, and sometimes even a pained expression. This is followed, almost always, by a common complaint often referred to as the criterion issue.

Despite sounding like a great name for a spy thriller, it refers to something rather more mundane, albeit critical. In this context it is the simple question, “How do we know whether a particular measure is linked to workplace success?”

The traditional answer is to look at whether measures are linked to individuals' performance in the workplace—for example, if we think that height is a sign of talent, we can test whether people who are tall do in fact tend to achieve higher levels of performance than people who are shorter. This may sound straightforward, but a big problem lurks here: how we measure performance. So before we look at how we can use measures of performance to improve talent measurement, let's first look at what some of the problems with measuring performance are.

Problems in Measuring Performance

In some roles, performance can be measured through results, for example, sales figures. Yet in most roles, there are no such straightforward results that can be used. Even when there are, using hard results as an indicator of performance is not always as perfect as it sounds. In sales jobs, for instance, there is the issue of whether it is fair to compare people who operate in different areas. As a result, researchers and vendors have tended not to use real results, but rather managers' performance ratings of people. Again, this may sound like a good solution, but it is not, for three reasons: lack of performance data, inaccurate performance ratings, and the fact that performance ratings can reflect many things.

Lack of Performance Data.

Researchers and vendors can often struggle to access performance ratings. We know, for example, of a FTSE 10 firm that has been using certain tests for its graduate recruitment for five years, but in this time, it had has not made performance data available to validate the measure. This issue is often less of a problem in the United States because of the legal necessity of proving validity. But elsewhere it is a big challenge. It often stems from the fact that due to system limitations, companies can struggle to access these data themselves and match them to test results. Yet it is also often an issue of will: they feel they have other priorities.

Inaccurate Performance Ratings.

Even when we can access performance ratings, they are not perfect indicators of actual performance. Ratings obviously reveal something about performance.5 Yet there is strong evidence that ratings do not reflect only performance. Managers typically give higher ratings to employees they like, and it is not unusual to find 80 percent or more of employees rated as “above average.”

Some companies have tried to address this issue by introducing forced ranking systems in their performance management processes. These require managers to identify a certain proportion of their employees as high and low performers. For example, they may have to rate 20 percent of their people as high performers, 70 percent as average performers, and 10 percent as low performers. Yet although these systems do stop the wide-scale overrating of performance, research has shown that they are not long-term solutions and can become counterproductive after a time.6

The quality of performance ratings can be problematic for researchers and vendors because for every bit that the data are slightly inaccurate or skewed, they reduce vendors' ability to accurately target measures to predict performance. Rather than predicting genuine performance levels, the data end up predicting the overinflated or skewed performance ratings.

Performance Ratings Reflect Many Things.

Finally, and perhaps most significant of all, is that researchers have mostly used just overall performance ratings—mainly because this is all that most companies measure. Yet researchers have found that overall performance ratings are not based only on task performance. There are other aspects of performance too, such as corporate citizenship and self-development, that all contribute to the overall performance rating. And, critically, many talent measures appear more able to predict these more specific elements of performance than overall performance.7 So, for example, there is evidence that conscientiousness is a better predictor of corporate citizenship than of overall performance.8

There is more: it also appears that talent measures may be better predictors of some types of performance than others. Research by the US Army, for instance, has found that intelligence is better able to predict task performance (with validities of 0.65) than “effort and leadership” (validity 0.25), “physical fitness and military bearing” (0.20), and “personal discipline” (0.16). Similarly, personality measures were found to be more strongly related to the physical fitness and military bearing dimension of performance than to task performance.9

In chapter 2, we saw that using more specific personality dimensions could lead to higher validity levels. What we now find here is that trying to predict more specific types of performance also increases the accuracy of predictions. Being more precise seems to be the way to go.

Measuring Multiple Dimensions of Performance

For vendors to be able to develop better tests and more effectively target measures, businesses have to start measuring more than just overall performance. Indeed, if they want to be better able to predict success and thereby improve their people decisions, this is arguably just as important as the need to start measuring fit. The big issue, of course, is how to do it.

Managers have increasingly broad spans of control, which means they have to invest a significant amount of time in performance management. The tendency has thus been to try to simplify and accelerate the process for them. Indeed, we recently saw an article in which a company boasted of having an appraisal form that takes a mere seven seconds to complete.10 Putting aside the issue of whether this is something to aspire to, the reality is that any suggestion of greater complexity in the performance management process is likely to evoke concern. We want to be clear here. What we are proposing need not, and should not, be either complex or time-consuming. It need not add much extra work, but it does have the potential to make the ratings far more meaningful.

In fact, there is already a move to do this, especially in the United States. Companies are increasingly looking to monitor and reward employee behaviors that are discretionary and beyond their formal job descriptions that add value to the organization. They are called different things, such as organizational citizenship behavior, prosocial organizational behavior, extra-role behavior, and contextual performance.11 But they mostly refer to the same thing—typically behaviors that contribute to making the workplace a better or easier place to work. Researchers have developed some detailed definitions and complex measures to help assess these behaviors. But managerial ratings need not be detailed or complex. They just need to be good enough.

Another increasingly common practice is competency-based performance management. This involves distinguishing between the results people achieve and the way they go about achieving them. This how element is usually measured through competencies, and it often contributes to 10 or even 20 percent of the overall performance score. This is definitely a step in the right direction. But the way it is implemented means that the data are often not useful for developing better talent measures. Managers are typically asked to rate a large number of competencies (we know one firm in which they have to rate eleven), which means the accuracy of the individual ratings tends to be low. Or they simply give an overall score for “behaviors,” which is too broad to be useful for our purposes here.

Measuring What You Value

The final foundation we are suggesting, then, is replacing the overall performance rating with three or four more specific ratings. The types of performance you measure should be driven by what you value as a business. Other types of performance sometimes measured in addition to task performance include safety-related behaviors, contribution to team performance, and self-development (the use people make of training). Importantly, these aspects of performance should not just be behaviors from a competency model. This is because competency models tend to change every few years, and ideally you want to be able to build up a database of results over many years.

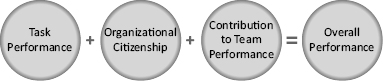

If you are unsure where to start, you can simply measure the following three dimensions (see figure 6.1):

- Task performance (how well objectives are fulfilled)

- Organizational citizenship behavior

- Contribution to team performance

Figure 6.1 Dimensions of Performance

An overall performance score can then be produced by combining the more specific scores, perhaps using a weighting scheme. For example, if you believe that task performance is the most important aspect of overall performance, then you could create an algorithm that reflects this. The rating for task performance could account for, say, 70 percent of overall performance, with contribution to team performance making up 20 percent and citizenship behavior contributing 10 percent.

Of course, as we suggested earlier, these kinds of data are of limited use unless you collect them centrally and connect them with other data. You need to link performance information to results from talent measures. Doing this will enable you to better understand what you are predicting with the talent measures that you use and more precisely ensure that you are measuring all of the factors you need to. But most important, by being more specific about what type of performance you are predicting, you will be able to achieve higher validity levels and thus be better able to accurately identify and measure talent.

Not all organizations will be in a position to implement such a change in how they measure performance. But it need not be complex or time-consuming, and it holds the promise of better measures, better tools, and better people decisions.

Proceeding from a Sound Base

In this chapter, we have looked at the foundational issues that underpin talent measurement. We have distinguished four issues that organizations need to address to ensure that measurement has the impact it should, discussed strategy and policy considerations, and described how businesses can improve the measures and tools available to them through measuring different types of performance. If firms are to go beyond merely using measures that work and instead make measurement work for them, they need to address these issues.

Although not all companies can or need to address all of the issues in this chapter, we are frustrated by just how often we find that even the basic, must-do tasks are not in place. Certainly using a central database, having common data points, and checking whether measures are sufficiently tailored to your company should be no-brainers. They are that easy. Just do it.

The fourth foundation, ensuring proper use, can be a little trickier in some businesses, especially large, diversified, or decentralized ones. Indeed, for some businesses, the issue can seem quite daunting. Yet there are simple things that they can do, and in the next chapter, we look at how organizations can ensure that they use the outputs of measurement—the information provided—to best effect.

Notes

1. Lawton, D. (2012). Personal communication. Cubiks, Ltd.

2. MacKinnon, R. A. (2010). Assessment and Talent Management Survey. Thame, Oxfordshire: Talent Q.

3. Tippins, N. (2012). Personal communication.

4. Ployhart, R. E., Ryan, A. M., & Bennett, M. (1999). Explanations for selection decisions: Applicants' reactions to informational and sensitivity features of explanations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(1), 87–106.

5. Murphy, K. R. (2008). Perspectives on the relationship between job performance and ratings of job performance. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1, 197–205.

6. Grote, D. (2005). Forced ranking: Making performance management work. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

7. Borman, W. C., Bryant, R. H., & Dorio, J. (2011). The measurement of task performance as criteria in selection research. In J. L. Farr & N. T. Tippins (Eds.), Handbook of employee selection. New York, NY: Routledge.

8. Borman, W. C., Penner, L. A., Allen, T. D., & Motowidlo, S. J. (2001). Personality predictors of citizenship performance. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9, 52–69.

9. Borman, W. C., Bryant, R. H., & Dorio, J. (2011). The measurement of task performance as criteria in selection research. In J. L. Farr & N. T. Tippins (Eds.), Handbook of employee selection. New York, NY: Routledge.

10. Brockett, J. (2012, June 18). Mining firm uses “seven second” appraisal forms. People Management Online. Retrieved September 14, 2012, from www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/pm/articles/2012/06/mining-firm-uses-seven-second-appraisal-forms.htm?utm_medium=email&utm_source=cipd&utm_campaign=pmdaily_190612&utm_content=news_3

11. Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; Brief, A. P., & Motowidlo, S. J. (1986). Prosocial organizational behaviors. Academy of Management Review, 11, 710–725; Van Dyne, L., Cummings, L. L., & McLean-Parks, J. (1995). Extra role behaviors: In pursuit of construct and definitional clarity (a bridge over muddied waters). Research in Organizational Behavior, 17, 215–285; Borman, W. C., & Motowidlo, S. J. (1993). Expanding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual performance. In N. Schmitt & W. C. Borman (Eds.), Personnel selection in organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.