Chapter 5

Solving the Career Growth Dilemma

Career issues remain the top reason that employees are voluntarily leaving their jobs in the United States. This trend has happened seven years in a row based on our national research. And it’s not always about upward mobility or a lack thereof. It’s about growth—growing skills and knowledge, gaining responsibility for roles and tasks, being exposed to things that make one better at one’s job, and so on. No matter what organization we’re talking about, employees care a great deal about these matters, particularly millennials. Because they care so much about these matters, having conversations between leaders and employees is critical, and yet these conversations are not happening as frequently as they should be.

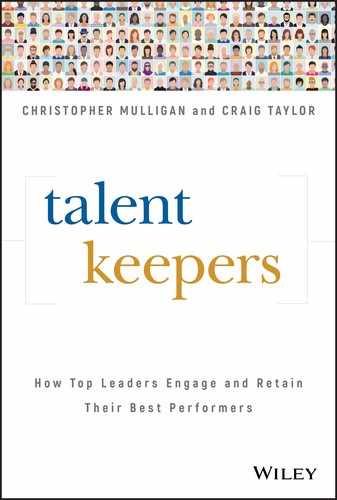

If an employee leaves in the first year, it’s most likely because they had missed expectations or were a poor fit based on the skills required. The next biggest reason is a lack of advancement opportunities. Figure 5.1 plots the biggest reasons employees voluntarily leave their jobs within the first twelve months on the job, excluding pay. We always exclude pay when asking these sorts of questions because everyone, even you, has a number—an amount of money for which you would leave your current job. Fortunately, even the allure of more money can be moderated by engagement. Research shows that if an employee is engaged, it will take at least 20% more pay to get them to leave simply for a higher salary. Conversely, if an employee is not engaged, they will leave for as little as 5% more, or even less.

Figure 5.1 Reasons that employees voluntarily leave their jobs in the first year.

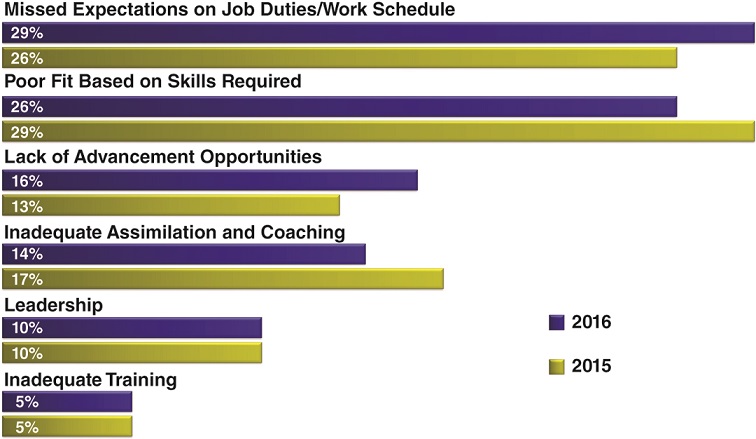

Employees who leave after their first twelve months on the job do so for varying reasons. Nearly half of all the reasons to leave for these employees are career driven, with “upward advancement” accounting for 30% of all reasons, followed by “lack of growth experiences within current role” at 19%. Figure 5.2 depicts the reasons employees leave after their first year on the job, excluding pay.

Figure 5.2 Reasons that employees voluntarily leave their jobs after the first year.

Clearly, career plays a central role in the “leave decisions” for low- and longer-tenured employees. The best person to have these conversations about career growth is the frontline leader. Unfortunately, not enough of them engage in these conversations, and for good reasons: First, some frontline leaders don’t think it’s their job to have these conversations (and why would they, since their bosses didn’t have these conversations with them?); second, they don’t want to make a mistake like promising somebody a raise or a promotion and then not being able to deliver later (this compels them to think that it’s better not to talk about career goals at all); third, it’s so much easier to tell an employee what she wants to hear rather than the truth.

That last point is huge, and we see it often. We see leaders telling an employee that she is doing a great job and is on “the list” of people in line for a promotion, then turning around and telling their leaders that this same employee is nowhere near ready for a promotion. Leadership takes honesty, which requires greater skill. It’s hard to tell people things they don’t want to hear, but the best leaders do so in a constructive, positive, and career-affirming way.

Recognize the Right Way

Everybody loves to be praised, right? Sure, but not everybody loves to be praised in exactly the same way. Just because Marissa really enjoyed that glowing speech you gave about her in front of everyone in the office doesn’t mean Jerome will too. Praise is a valuable component to the manager/employee relationship, but only if that praise is personal. This means that the best leaders make the message unique to what each individual values most.

You don’t want to attempt to do something good by recognizing someone publically if they would prefer private recognition (that’s one great way to turn a positive into a negative). If this person would love to have an email that she can read over and over again, then don’t miss that opportunity by simply praising her face-to-face. The flip side is also true. Some people much prefer face-to-face recognition—and that includes millennials, believe it or not. Some like to be treated to lunch. Others would appreciate a handwritten note.

Bertha Johnson highlighted what they are doing at the city of Durham to determine individual preferences for each employee. Their E-3 (Employee Engagement Exercise) Program assists supervisors with employee engagement by helping them learn how they like to be recognized for their successes. The program also helps bring to light the strength and skills that each employee likes to use on the job, and what areas they would like to focus on in developing their talents. “Developing a partnership involves each party recognizing the other’s contributions, strengths, and preferences,” Johnson said.

Here’s another example: While we were working with that same communications company, we found that the market with the highest engagement scores and business metrics (both sales and service) got there in part because of one tremendous action one of the vice presidents (VP) was doing. The highest-level leader in this market was sending handwritten notes to frontline employees who had achieved certain criteria or met specific goals. Over the course of three months, that VP had sent over two hundred of these notes. These notes became highly valued in the market of 1,500 employees. Now we’re talking about 15 to 20% of the people working in this market had received a handwritten note of congratulations and praise.

And here’s the really powerful part: Most of the recipients didn’t take these notes home or stash them away in their desks. Instead, they would put them up on the bulletin board in the back of the store. This allowed them to show how proud they were to have been recognized, which in turn raised morale considerably. It got to the point where people would clamor to see who would be the one to go get the mail that day in the hopes of finding another letter from the VP.

Imagine the value of this action. How much does it cost to write a note? It costs nothing. In fact, recognizing an employee for a job well done never has to cost a dime. Recognition is free, but it goes a long, long way.

Trust Each Other with Your Careers

Early in TalentKeepers’ history, we received a couple of emails from someone claiming to be with the CIA. This person said he wanted to hire us to help with engagement and retention within the agency. We deleted the emails, figuring they were a prank by some colleague looking to make us laugh. But then we got a call. “Really,” the caller said, “I’m with the CIA. Please don’t hang up on me.”

Still sort of in disbelief, we listened as the contact explained that his organization was struggling with retaining agents.

“I’m not sure we can help you,” we said. “We work with retailers, call centers, and other professional environments. We deal with trust, communication, coaching, and career issues.”

“Those are the exact reasons people leave the CIA,” the contact insisted. “In the field, we trust each other with our lives, but when we return to the office, we don’t trust each other with our careers.”

We agreed to work with them.

As we transition into this chapter and delve deeper into the subject of career conversations, keep in mind that the higher you rise up the leadership ladder, the harder it is to have these career discussions. After all, the higher you climb, the fewer the opportunities you have to advance. Intraleadership dynamics become more acute when the people doing the talking are more competitive. In some ways, it’s easier to trust someone with your life than it is to trust them with your career.

Shifting Career Aspirations

Picture yourself as a frontline employee in your organization. Let’s imagine that you’ve been in your role for three years. During that time, you have gotten to know, respect, and enjoy the company of your immediate supervisor. He is a great boss. He always speaks to you about what you need and expect to receive from your job. He coaches you and helps you evolve into a genuinely spectacular contributor to your team. Because the two of you have had so many conversations over the years, you feel confident that he knows your aspirations to be promoted into a leadership role—and in fact, that you aspire to rise to the director’s chair one day. You enjoy coming to work in part because you like working for your supervisor, and also because you feel confident you have a future here.

Now let’s imagine that this supervisor of yours has just announced that he will be leaving his position for a promotion in another department—or worse, maybe he’s leaving the organization altogether. Now, that amazing person to work for and that great advocate for your future with the organization is gone. His replacement is someone you’ve never even seen before, let alone met or with whom you’ve had the chance to work. What’s your first concern? Well, your first concern might be about all the subtle changes that might add up to a big difference in your day-to-day routine. The new boss is likely to have her own way of doing things and her own set of expectations, so what is that going to mean for you? That’s scary enough, and in fact, for some people, it’s sometimes plenty of impetus to start looking for another job. The mutual trust and commitment you shared is walking out the door.

You, though, are invested in this organization and can still envision yourself working here ten years from now. So what’s your next thought? Probably you’re worried that all those conversations you had with your former supervisor—concerning your expectations, your goals, your needs—have just gone out the door with him. Now you’ll have to start over with this new person and hope that she gets you, respects you, and wants to help you as much as your former supervisor. Will your new leader share the same commitment to your growth and aspirations as your old boss? That might seem like a long shot. After all, your former supervisor was your favorite boss ever, and in no small part thanks to his uncommon willingness to listen, bond, and do what he needed to do to make you feel valued and on track for that promotion.

These are the effects of an organizational change, and as we discussed in the previous chapter, change—both organizational and personal—can lead to an erosion of engagement. Your commitment to your job and the company remains strong, but your productivity may suffer in the coming days, weeks, or even months in part because now you’re thinking about how, at best, you’ll have to go in to talk to your new supervisor and regurgitate all that information that your former supervisor already knew. Then you also have to hope that this new supervisor will agree with you that your goals are important and that you’re capable of meeting those you set.

But imagine how the conversation—and indeed, your impression of your new supervisor—changes if that new supervisor comes to you and says, “So I was just reading these notes on your goals, needs, and aspirations with the organization. This is all really great. I was just wondering if you could update me on what’s left to do here? Where do you feel like you are in this timeline you’ve set? What kind of progress have you made? How do you see that you’ve changed in your role and improved the team? What do I need to do to take you to that next level?”

That’s a totally different and an entirely powerful conversation. As a frontline employee, now you’re realizing that your new supervisor is taking the time to learn about you and show you she cares. You understand that, like your old boss, this new boss isn’t going to treat you like a number. She’s going to treat you like a person who has values and is valued. It takes the conversation from, “So, tell me everything I need to know about you and what you do here,” to “Tell me what’s important to you right now so I can help you get it.” A leader who is equipped to say something like this—especially if that leader is then skilled enough to shut up and listen to the answers—has nearly everything she needs to solve the career dilemma. It doesn’t matter whether you’re speaking with a boomer or a gen Xer or a millennial; everyone appreciates this kind of conversation, and that appreciation goes a long way toward improving engagement.

The Stay Interview

You’ve heard of exit interviews. You’ve probably even conducted or sat in on a few. Their value to any organization is tremendous, because here we have an opportunity to learn from a departing employee all those factors that are causing him to leave. This allows us to assess how we might make changes to prevent similar departures from happening in the future. This data is incredibly useful, which is exactly why such a high percentage of organizations employ the strategy.

What would make this kind of data even more useful would be if your organization gathered it throughout every employee’s career life cycle. Many organizations get a part of the way there by implementing selection and onboarding programs that include some form of assessment or evaluation that can be used to learn more about the new employee’s potential for growth. They may ask the right questions about each incoming employee’s goals, needs, and expectations. Unfortunately, too many of these organizations then stick that information in a drawer and never revisit it—at least not until it’s time to conduct the exit interview. So what about all the in-betweens? If we look at the time between when an employee starts and when an employee leaves, are we thinking that the employee’s goals, needs, and expectations don’t matter anymore? Or are we under the impression that they never change?

Of course they change. These factors are in flux throughout the career life cycle, right along with the knowledge, skill, and engagement of each employee. This is why we advocate for organizations to collect the appropriate data early and often, keep this data with the employee, and revisit it as often as possible.

One key to attacking the career dilemma is to use a systemic approach. Start by gathering information from each employee, and building on this data with each subsequent (ideally monthly or at least quarterly) conversation between leader and employee. If you talk to the people you count on frequently, you have a much better understanding of who they are, what they expect, what they need, and what it will take to compel them to stay with your organization. That information is so much more valuable and actionable than the exit interview data related to why that employee left you.

Conducting these stay interviews on a regular basis through a short questionnaire also allows the organization to aggregate the data, which opens leaderships’ eyes to what their employees want at any given time during their tenure. New hires from one generation tend to value and want different things than longer-tenured employees from other generations. People occupying one role within an organization often share preferences that differ from people occupying another. Knowing these differences and having this key data at hand allows leadership to take action and ensure that everyone is having their expectations met. If trust is the most important point across the board, for example, then how have you engendered trust between leaders and their teams? Stay interviews allow you to audit your own career offerings and see how they fit with your team’s needs.

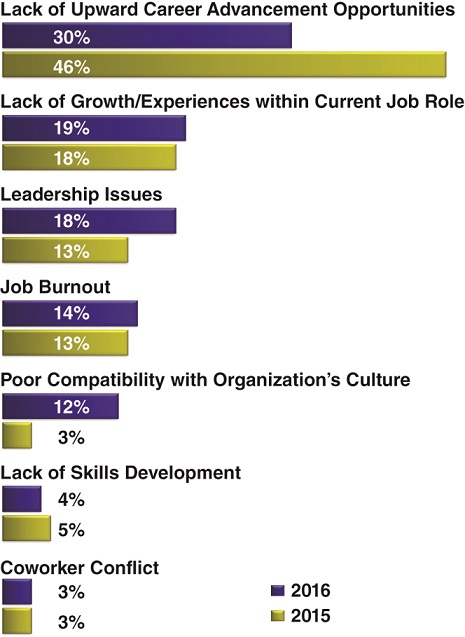

Stay interviews are well worth the effort. Figure 5.3 shows the financial benefit one of our clients realized by using stay interviews to increase retention. These types of positive returns are almost always achievable when stay interviews are properly implemented.

Figure 5.3 The financial benefit a client realized by using stay interviews to increase retention.

The stay interview strategy also helps solve the dilemma we presented at the opening of the chapter. If this data follows the employee, then even a leadership change can be seamless in terms of its effect on engagement. The stay interview data allows the new leader to discuss with each team member everything that has already been documented, reference that documentation in the future, and always know how to make sure the leader is meeting the needs of each employee.

Good survey data—whether gathered anonymously as with most engagement surveys or nonanonymously as with a stay interview survey—can provide valuable information for an organization. A major hotel chain recently presented an anonymous survey to all of its employees in a certain category of its business. The responses they received from these employees were surprising at times, but always valuable. They learned the more surface-level data like the notion that they were losing 48% of new hires in less than six months while retaining only 6% for more than five years. It seemed that most employees who left did so for personal reasons, but job abandonment, new job opportunities, and a failure to meet job expectations or company policy rounded out the top five. You know what reason was at the very bottom? “Dissatisfied with pay.” For some in the organization’s leadership structure, that came as a huge shock, as the impression had always been that attracting better talent meant paying better wages. Across the board, this is simply not so. Pay is important, but it only goes so far.

The truth was that most respondents, regardless of background, were far more interested in questions about how they would get recognized in front of the team, whether rumors about changes in workflow or leadership were true, and how they might move up the ranks with a promotion. Many respondents who admitted to lower levels of engagement suggested that they wanted more variety in their work and wished they felt more challenged. These factors mattered a great deal to nearly everyone who took part in the surveys. It’s no surprise that they all have to do with the quality of leadership.

What Causes People to Stay?

What do you think employees prefer most in a leader? The top preference is trust. Frontline employees in every organization we have ever worked with want to feel like they can trust their leaders and that their leaders work to build trust within the teams. Then comes the matter of communication, followed by retention, followed by development and coaching. People feel more secure in their careers and valued at work if they report to a leader they can trust, someone who is open and honest with them, someone who understands what it takes to keep them happy and productive, and someone who offers them opportunities to improve their knowledge/abilities and expand their roles.

You know what else is interesting about that hotel chain’s surveys? With all the preaching we’ve been doing about the different preferences between different generations, when it comes to preferences about leadership qualities, it did not matter whether the respondent was a boomer, gen Xer, or millennial. Everyone valued trust, communication, retention, and talent development in at least their top five. The same was true regardless of tenure. Whether you’ve been with the organization for less than six months or more than five years, trust remains squarely at the top of your list. Communication sticks around in the top three, while retention and talent development stay in the top four. This organization employs people who work on-site and from home, and the survey also revealed that the environment mattered little either. Whether on-site or off, respondents overwhelmingly favored trust, communication, retention, and talent development.

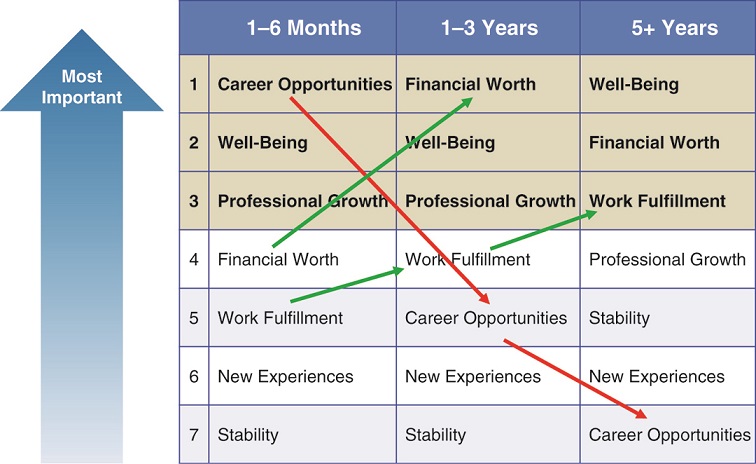

When it came to career preferences, the organization learned that maintaining a work-life balance trumped even the opportunity to increase or maintain compensation based on contributions. Having fulfilling work to do rated nearly as high as compensation, as well. Professional growth and new opportunities also checked in as key values. The interesting part? When it comes to career preferences, tenure and generation do matter. For the employee who has been around for less than six months, career opportunities top the charts. That’s only natural, of course. When you’re first starting with a new job, your main concern is how you can advance your career. In years one through three, financial worth rates as the highest factor. This should come as no surprise, either, given that people tend to focus on making money as they establish themselves in a new role. And what do people who have been around longer than five years value the most? Well-being. If you’ve been with an organization for a long time, your primary concern shifts to work-life balance. By now you’re comfortable in your role and with your compensation. Now you just want to find a way to feel rewarded and enjoy your work while still having plenty of time and energy for your family. Figure 5.4 shows how career preferences varied by tenure in one client organization. Expect these variances in yours, too.

Figure 5.4 Variation in career preference by tenure.

Interestingly, work-life balance was ranked highest for gen Xers and baby boomers, but it came in third for millennials, the generation with whom many people have associated a focus on work-life balance. For millennials, compensation was the highest rated factor, followed by career opportunities and then well-being. For boomers, the preferences were practically reversed, with career opportunities ranking at the bottom.

What can a leader do to ensure that every employee feels as if their needs are understood and being met? Regular stay interviews go a long way, but as we mentioned in the previous chapter, you also have to know how each individual values engagement and recognition interactions with their leaders. Do they prefer in person, email, a phone call, recognition in front of the whole team, lunch, a handwritten letter?

By a wide margin, respondents in the hotel chain’s survey, and every survey of the sort that we have ever conducted, ranked in person the highest for both engagement preferences and recognition preferences. Faceless modes of communication like email and phone calls scaled farther down the list, with team announcements trailing behind. It might surprise you to learn that, out of all respondents, millennials were the ones most likely to value in-person meetings about engagement and recognition. Millennials are supposed to be the ones constantly glued to their phones and living in a world of social media communication. Even so, they preferred in-person engagement meetings at a 67% rate versus gen Xers and boomers, who preferred them at 49% and 50%, respectively.

Tenure matters little regarding communication preference. No matter how long the employee has been with the organization, she tends to prefer in-person meetings. They value it highest when they have been in their roles for less than six months, but it remains the top preference throughout an employee’s time with the organization.

“The bottom line is that the leader should believe in employee engagement,” said Donna Fayko of North Carolina’s Rowan County. “It is important to understand how critical it is to create a work-life balance for staff. You also should keep in touch with the ways you motivate the different generations that you’re hiring. Some millennials are so energized that they believe they can start on day one as a frontline worker and become the director by the next day. When expectations are so high, you have to find creative ways to keep them engaged.”

In Donna’s view, communication and knowledge are power. “Open communication between all levels of leadership in your organization is the ultimate goal. Not all decisions should be made at the top. The opening of communication and the sharing of power creates better partnership and collaboration.”

More than anything, making people want to stay is a matter of (1) keeping it fun, and (2) giving them opportunities to advance. At Rowan County, employees dress up for Halloween, hold an annual Super Bowl party, regularly sponsor games and friendly competitions, and so on. They also believe in standardized supervision and coaching, training newcomers toward success, and demonstrating opportunities for upward mobility by way of lead-worker routines and other informal leadership opportunities for frontline workers hoping to advance. “The idea is to avoid people getting stagnant in their roles,” Donna advises. “Anytime you can give staff an opportunity for growth, it will benefit you.”

Career Growth and Accountability

We know what needs to happen if we hope to engage and retain more talent: Leaders have to conduct these stay interviews regularly with every employee, and ideally, they need to do it in person. It all seems pretty cut and dried, so why aren’t these kinds of career conversations happening more often (if at all) and in more organizations?

The surface reason is simple: Most leaders don’t know who’s responsible for having these conversations. Some think this is the role of human resources. Some think it should fall to the frontline leaders. Others believe it should be senior management’s responsibility. Well, let’s resolve this issue right here and now: These conversations need to be happening between frontline leaders and frontline employees.

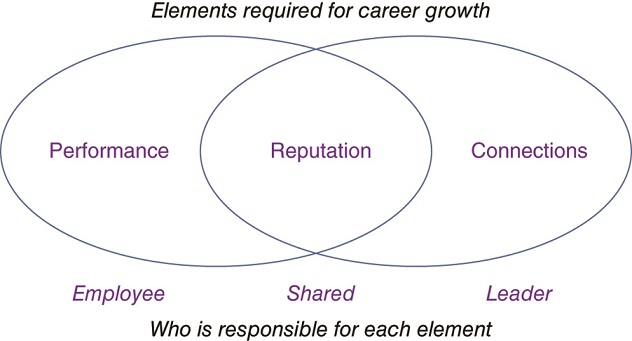

Clarity about who is responsible for these conversations is critical. Absent clear roles and accountability for having these conversations, your leaders and employees will flounder, and too few employees will have a career-growth conversation, which greatly increases the chances they’ll become disengaged and leave. We have developed a model to depict what should be considered for career growth and who should be accountable for it. We call it the Career Growth and Accountability Model, which is shown in Figure 5.5.

Figure 5.5 The Career Growth and Accountability Model.

We must address three key factors, and we will do so in depth in a moment, but first, keep in mind the big picture: As leaders, the perception we’re striving for is that we’re trustworthy, honest, and open in our communication and our presentation of opportunities to each employee. The perception needs to be that the way you get promoted at this organization is transparent and objective. Every employee must believe that if he works hard and does what’s valued here, the sky is the limit. No one has to do any sucking up or jockeying to get on the “good list.” It’s all about effort and results. This perception eliminates favoritism, ensures that everybody remains in the loop on what is expected of them, and keeps your best talent with you.

Performance

A prerequisite to getting career growth opportunities is to perform well in your current role. The employee is primarily accountable for her own performance. The leader is responsible for setting performance expectations, providing feedback on how the employee is performing, and giving appropriate coaching to help the employee meet the expectations. Highly effective leaders understand that it is their job to train every employee to reach performance goals and that level of competence necessary to taking on new responsibilities and even new positions in the organization. However, at the end of the day, the employee has to perform. Each employee must understand that her current job is the springboard to any other job in the organization. If she is underperforming in her current job, the probability of advancement goes way down. The accountability for performance falls squarely on the employee.

Reputation

Reputation includes everything from your work ethic, your dress, your willingness to volunteer, your willingness to go above and beyond, how well you get along with others, and so on. You need the right reputation if you’re going to advance. At first glance, this might seem obvious, but many people, regardless of tenure or background, are often unaware of what a key role reputation plays.

A leader needs to be honest with employees before they will begin to understand the importance of reputation. Likewise, the employee will have to embrace the notion. These two things can’t happen if the leader isn’t conducting regular discussions on performance and career aspirations with the team member. After all, how can the leader know for certain what is causing these reputation issues if she doesn’t ask? If you have an employee who never stays one minute past 5 p.m., the surface assumption might be that this employee is lazy, not dedicated, or hates this job so much that he can’t wait to get home at the end of the day. But what if the truth is something much deeper than that? What if that employee has no choice but to leave immediately because he has to pick up a child from daycare no later than 5:30? Then, the perspective changes. Additionally, team members may have some blind spots regarding certain elements of their reputation. Therefore, the accountability for reputation is on both the leader and the employee.

Connections

The connections factor has two elements. The first is this: As a leader, I want to connect this person who wants advancement to other people in the organization who may be able to offer that individual opportunities for career growth. I need to be talking up my talent. When I hear about another leader who needs help with something that I feel would be a great fit for a talented employee, I need to express what a great candidate she would be for the role.

The second element is that I must allow my team member to learn more about other areas, responsibilities, or roles in the organization that may interest him. For example, I might arrange for him to have coffee with another supervisor from another function so he can learn more about what that function does. Then the employee can make an informed decision about whether this will fit his needs. The accountability for making these connections falls largely to the leader.

The greatest value of the Career Growth and Accountability model is that it clarifies roles and responsibilities for career growth, and thereby helps to address some common misunderstandings that cause so many leaders to hesitate when discussing career issues with team members. Once again, this is the clearest path to a more engaged and talented workforce.

Job Stratification

Since career growth is such a powerful engagement and retention factor, we developed a tactic to provide more opportunities for career growth called “job stratification.” This structural tactic opens up more levels of opportunity to grow employees into skills, experiences, and eventually, roles. Rather than having just two levels of employment—leader and frontline employee—many organizations create new titles and responsibilities that set teams up with more frequent steps toward the top. Some organizations call these roles things like “Team Leader 1, 2, and 3,” and others go with the more traditional “assistant supervisor,” “associate supervisor,” “senior supervisor,” and so on. The idea is that designating more roles with different titles and increasing responsibility not only gives the employee the sense of more room for advancement in shorter order (something that plays especially well with millennials), it also helps better prepare each employee for that ultimate leadership role, as they can learn pieces of that particular job in small doses over a longer period.

WOWs, Wet Socks, and Snorkels

We have already seen how employees from different generations or tenures will value at least slightly different things. However, we also know that different employees perform at different levels, and as such, they must be managed differently. You can’t manage your most talented employee in the same way as your employee with the lowest performance levels. The great leader must tailor the message and the management style to the skill of the employee and to their position on the career spectrum.

In our research, we have found that one particularly effective tool for leaders to use is to categorize each member of the team into one of three performance groups. This exercise is valuable enough on its own, but the best practice is to then have each team member assign themselves into one of the three groups as well. This helps both leader and team member understand where perceptions of performance might be differing. Having these clean and clearly identifiable categories helps open up the communication and get everyone on board with where they stand and what they need to do to advance.

What are the categories? As the title to this section suggests, they are “WOW,” “Wet Socks,” and “Snorkels.” The acronym “WOW” stands for “Walks on Water.” The employees who fall into this category are your absolute top performers. “Wet Socks” are your second-tier performers, so named because they often walk on water, but occasionally stumble and get their socks wet. Tier three are your Snorkels, who get their names because they operating somewhere below the performance line—or in other words, they’re usually underwater on their work, and need a snorkel to breathe.

It doesn’t matter what kind of team you lead and what kind of organization you work for; you have at least one person on your team that fits into each of these three categories. The goal, then, is to get the snorkels above water, coach the wet socks to be WOWs, and create an environment where WOWs flourish.

Of course, you need three different approaches to manage the employees in each category. You can’t interact with and coach a WOW in the same way you do a snorkel. The first step is knowing the qualities of the people with whom you’re dealing.

WOWs

WOWs are really good at what they do. They’re creative. They think through things that even you as a leader might not have considered. A good leader surrounds himself with WOWs, even if those WOWs are better and more talented than he is.

When you give a WOW an assignment, the best way to describe that assignment is to focus on the outcomes. “Here’s what we need. Here’s what success looks like in this project.” The best leaders will tell their WOWs every possible angle to success on a given task or project, but they never tell them how to get there. For a WOW, if you tell them the how, you remove the opportunity for them to wow you with their solutions (pun very much intended). WOWs often find solutions that go above and beyond what you as the leader might envision on your own.

Now, of course, we aren’t all comfortable with handing things off to someone else and hoping their strategies deliver. To mitigate risk, you can ask a WOW to go and think about what they would do to achieve the results you’re looking for before they come back and present their strategy to you. This gives you an opportunity to adjust that plan to make sure it’s feasible and appropriate. If that sounds like macromanaging, that’s because it is. Macromanaging is the only way to effectively manage a WOW.

Wet Socks

Wet Socks are an intriguing group because they have shown flashes of potential to reach that WOW level. The first thing to ask a Wet Sock is whether they’re willing to put in whatever effort necessary to become a WOW. Not everyone answers in the same way. They might be a Wet Sock because they don’t aspire to reach that next level. Or it could be that they weren’t aware that they weren’t already on that next level. Or maybe they have an extra issue at home, like an aging parent or a sick child, which prevents them from putting in the extra time that may be required to become a WOW. Whatever the case, the message needs to be, “I think you can excel in your role and be great, but it’s going to take some work. Are you interested?”

If they say yes, the next question is, “Are you aware of what is preventing you from being a WOW?” Most people don’t see these dynamics intuitively. Self-reflection is difficult to manage. Most people have a blind spot regarding the factors that are preventing them from being great.

Once you have been open and honest with each other about where the employee stands and needs to improve, the conversation can shift toward discussing what the worker can do to overcome current issues, improve themselves, and reach that next level. Once you discuss mutually agreed-upon performance goals and timeframes for achieving them, you have an effective start to moving a Wet Sock to a WOW!

Snorkels

With Snorkels, micromanagement becomes necessary. You need to get granular on what is preventing them from achieving at least an acceptable level of performance. For example, imagine a salesperson consistently misses their quota. In this case, you need to start talking about the basics. “How many interactions are you having with potential customers every day?” If that number is too low, then you know that the employee has no hope of ever reaching the goal, and increasing the number of prospects the employee speaks with daily is a good place to start. On the other hand, if it’s the right number, then the conversations shifts to what exactly it is that this employee is saying to the customer. For Snorkels, ask questions such as, “How well do you understand the product? How are you addressing the customer’s concerns? How is the conversation going?”

The best practice in this case is to observe the Snorkel’s behavior in the field. Give input and suggest specific behaviors that need coaching. Do this daily. Micromanage. Based on the answers you receive, you will learn whether this person is capable of learning and advancing.

No matter which level of employee you’re speaking with, always remember to be honest. If they’re going to improve, they need to know clearly where they stand, even if that conversation is difficult. Once you have had that open and honest communication with your employees, asking your leader to rate those same employees is often a positive step. This helps you see the picture more objectively. If there isn’t agreement—whether between you and your employees or you and your leader—then you know you have work to do. If your Snorkel thinks they’re a WOW, they’re going to resist coaching, because they think they’re already great. In cases like these, you will need to invest more time and effort into delivering the message and helping the employee rise.

As a final point, don’t wait on this. The longer you wait, the longer it will take you to determine whether your Snorkels will advance. You will also have employees spending more time in a role that isn’t suited to them. Maybe this person is a Snorkel because she is not in a job that fits her purview. Maybe she would be more valuable elsewhere in the organization.

The greater damage by not acting now is that if you do not address Snorkels, you stand the chance of losing WOWs and Wet Socks to other organizations. Winners, after all, want to work for winning teams. In this way, Snorkels have more impact than on their own performance. Their poor performance could drive down morale and even compel high performers to leave.

In closing, remember that leaders need to embrace career conversations with employees. Focus the discussion on what drives the employee at work, where she is on the performance continuum, and what steps will help keep her engaged. This is leadership, not management.