Chapter 2. Windows on Candlestick Charts

Now that we have covered the basics of what gaps are, let’s look at how gaps are viewed on Japanese candlestick charts. Japanese candlestick charts display the same information (open, high, low, and close) that bar charts display but in a more striking way visually. Also, special vocabulary often accompanies the candlestick charts. For example, in Japanese candlestick charts, a gap is referred to as a window.

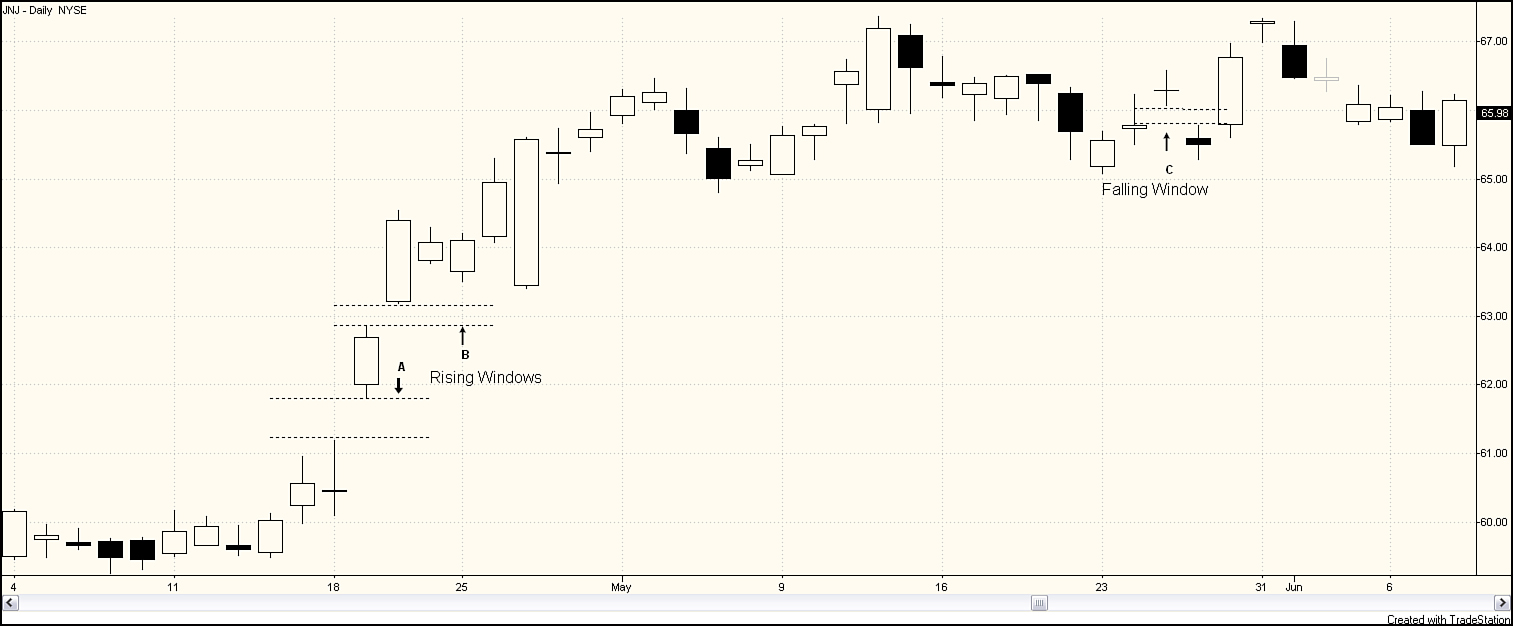

The candlestick chart of Johnson & Johnson (JNJ) in Figure 2.1 shows gaps, or windows, at points A, B, and C. For a window to occur, there must not be any overlap between two adjacent candles. For a window to occur, space must exist between the shadows of adjacent candles; because of this space, windows are also known as disjointed candles. In Figure 2.1, the real bodies of the candles on April 14 and April 15 do not overlap, but the shadows overlap; thus, a window does not occur.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 2.1. Rising and falling windows, candlestick chart for JNJ, April 4–June 8, 2011

A gap up is referred to as a rising window. Windows A and B are examples of rising windows (refer to Figure 2.1). In his book, Japanese Candlestick Charting Techniques,1 Steve Nison states that Japanese technicians view windows as continuation signals and say to “go in the direction of the window.” Thus, rising windows are considered bullish. When, a window occurs with a large white candle (refer to Window B in Figure 2.1), it is a running window because the market is said to be running in the direction of the window.

A down gap, such as the gap that occurs at Point C in Figure 2.1, is known as a falling window. Falling windows are considered bearish.

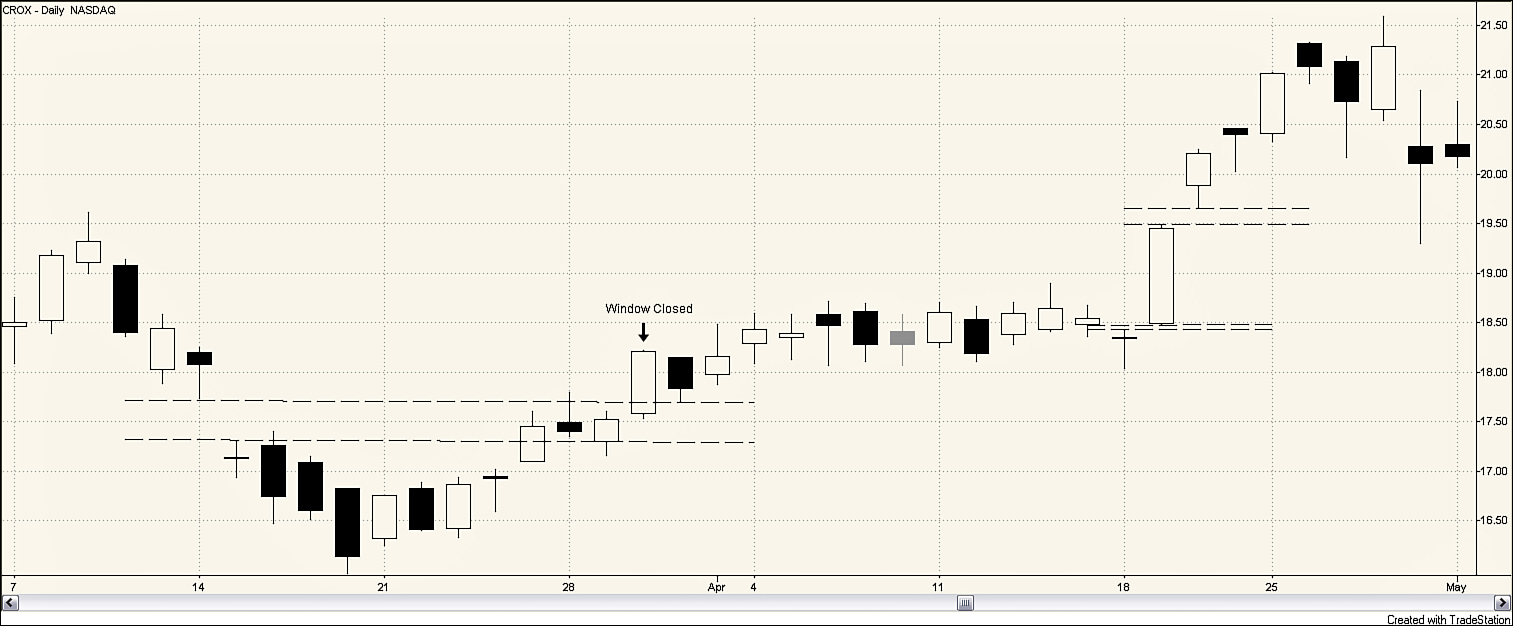

Closing the window is simply filling a gap. Refer to Figure 2.1 to see that the falling Window C is closed the following day. For a window to be closed, the real body of a candle must close beyond the window,2 as shown in Figure 2.2 for CROX. A falling window occurs on March 15. The upper shadow of the March 28 candle rises above the window; however, the real body still lies within the window. The window is not closed until 2 days later when the real body of the March 30 candlestick closes beyond the gap.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 2.2. Closing the window, candlestick chart for CROX, March 7—May 1, 2011

Some Japanese traders claim that if a window is not closed within three sessions, it is confirmation that the market should continue to move in the direction of the window. These traders see these unfilled windows as an indication that the market has the power to continue its trend for 13 more sessions. In his book Beyond Candlesticks,3 Nison questions the preciseness of this claim but supports the notion of waiting three sessions for confirmation of a price trend (p. 100).

Windows as Support and Resistance

In candlestick charts, rising windows become support zones, and falling windows become resistance zones. Thus, you hear Japanese candlestick chart analysts stating that “Corrections stop at the window.” Look, for example, at the September 1 rising window in Figure 2.3 (ATVI). The price initially moves higher in the direction of the rising window. However, on September 16, the price falls into the support zone. The price approaches but does not close below the 10.75 August 31 high. Because the window is not closed, traders can use this correction as a buying opportunity.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 2.3. A gap as support, candlestick chart for ATVI, August 30–November 2, 2010

Remember that a window can be large or small. A one-point rising window is still a window and serves as a support zone. According to Nison, the size of a window does not impact the importance of the window’s role as a support or resistance zone. However, a large window has the disadvantage of creating a large zone. What does seem to be a factor in determining the importance of the zone is the trading volume for the gap candle. Heavy volume tends to enhance the effectiveness of window support and resistance zones.4

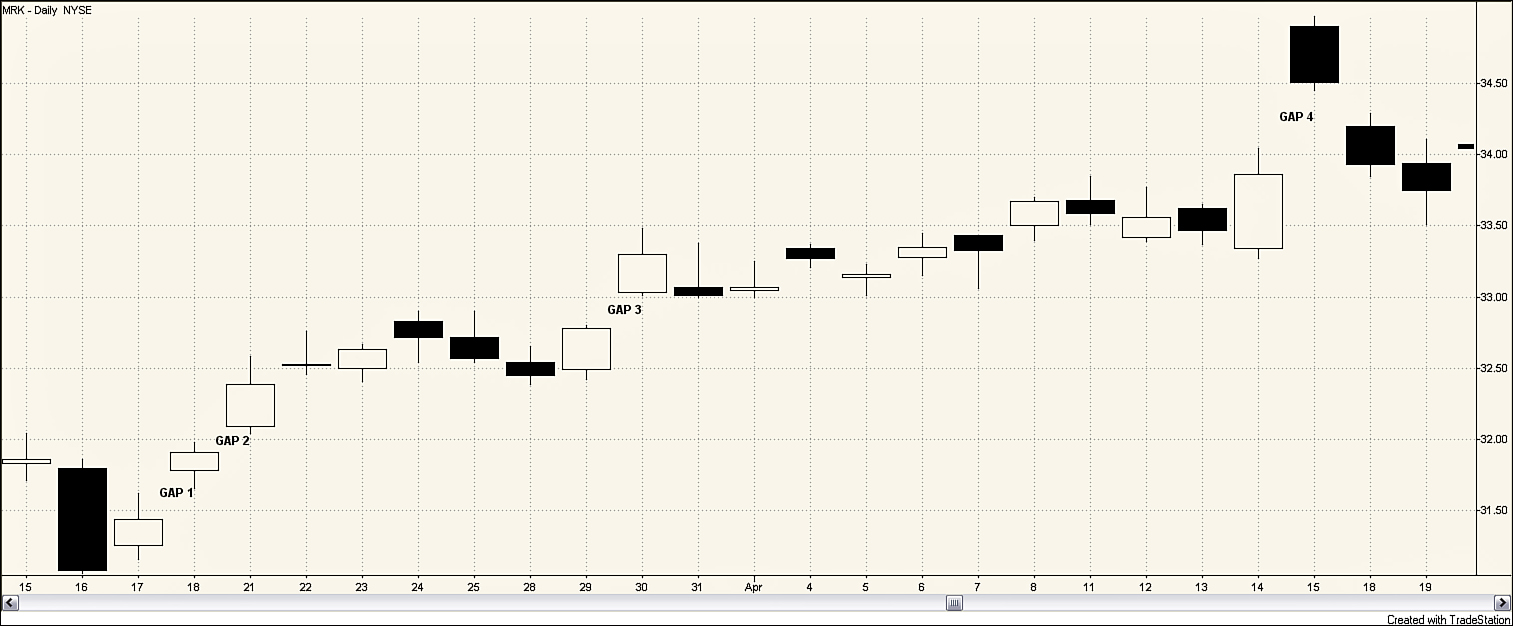

Traditional Japanese technical analysts place particular importance on the occurrence of three up (or three down) windows. After three up windows occur, the market is probably overbought; and after three down windows occur, the market is probably oversold. As shown in Figure 2.4, these windows do not need to occur on consecutive days. Three unclosed rising windows occurring during an uptrend would suggest an overbought market. Nison suggests that this idea comes from the emphasis that Japanese place on the number 3. In his experience, traders should consider the uptrend in place until the most recent window is closed rather than as soon as the third window rises. Refer to Figure 2.4 to see four rising windows. However, the fourth window is immediately closed, suggesting that the uptrend has come to an end.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 2.4. Four rising windows, candlestick chart for MRK, March 15–April 19, 2011

Remember that, in general, a rising window is bullish and a falling window is bearish. This is especially true with high-price and low-price gapping plays. Figure 2.5 portrays a high-price gapping play for Krispy Kreme Donuts (KKD). An advance in price of about 18% at the beginning of May is followed by a consolidation period. This consolidation period is composed of small-bodied candlesticks and signals a period of market indecision. The breakout from the consolidation occurs on a rising window, which is viewed as bullish. Indeed, the price of KKD continued to advance through June to $10 a share.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 2.5. High-price gapping play, candlestick chart for KKD, May 1–July 5, 2011

A low-price gapping play is simply the reverse of the high-price gapping play. A downtrend is followed by a period of small-bodied candles. During this consolidation period it appears that a base may be forming. However, a bearish falling window indicates that this was not the case, and the downward trend in price should resume.

Candlestick Patterns Containing Windows

Although many candlestick patterns have Western equivalents, some patterns are unique to candlestick charting. These patterns often have intriguing names stemming from their Japanese heritage. Most candlestick patterns are short term and composed of one to five bars. Patterns are defined by the relative position of the body and shadow of a candlestick and the location of a candlestick in relation to its neighbors. Candlestick patterns that contain windows within the pattern are described below.

Tasuki

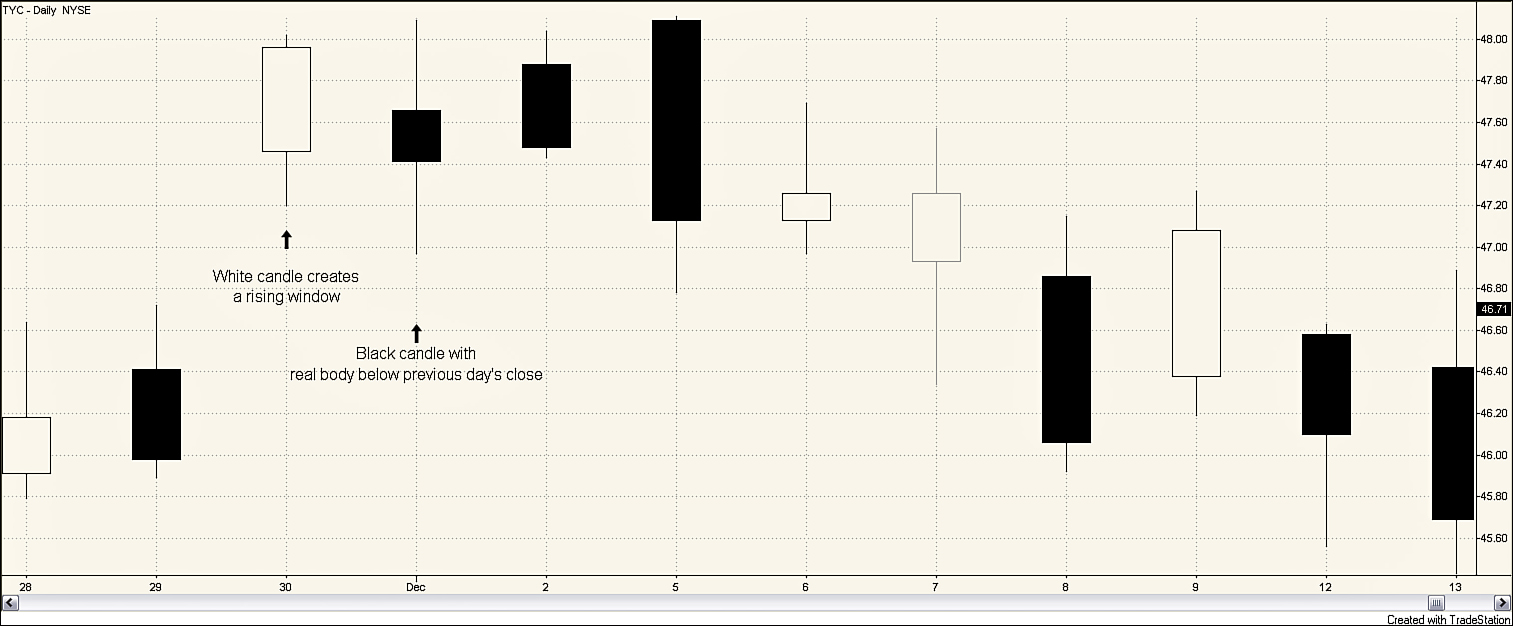

The tasuki is a two-candle pattern. The upward gapping tasuki is composed of a rising window created by a white candle followed by a black candle that has a real body top that lies below the close of the previous session’s close. The real bodies for the two candles are about the same size. Figure 2.6 shows an upward gapping tasuki for Tyco (TYC) that occurred December 1, 2011.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 2.6. Upward gapping tasuki, candlestick chart for TYC, November 28–December 13, 2011

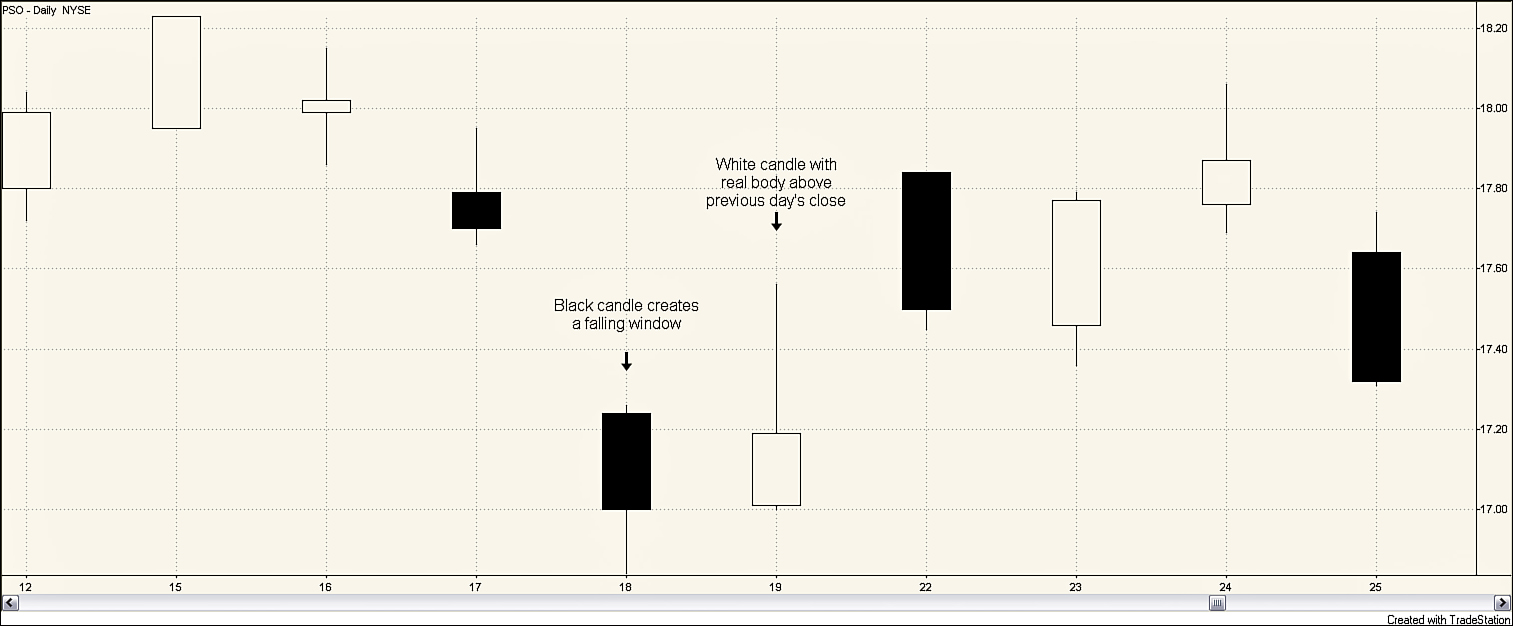

The downward gap tasuki is simply the reverse of the upward gapping tasuki. Figure 2.7 shows a downward gapping tasuki for Pearson (PSO). First, a black candle on August 18 creates a falling window. Second, a white candle occurs on August 19 with a real body about the same size as the black candle’s real body. The real body low for this white candle lies above the close for the black body candle. The real bodies of the August 18 and August 19 candles are roughly the same size, and the window is not closed by the August 19 white candle.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 2.7. Downward gapping tasuki, candlestick chart for PSO, August 12–25, 2011

The tasuki candlestick pattern is identified by the colors, relative sizes, and relative positions of the candlesticks on the day of and the day following the window. However, these characteristics do not appear to have a significant impact on the importance of the window. The significant items are the direction of the window and whether the window is closed. Thus, although interesting for informational purposes, identifying the tasuki pattern in not extremely useful to a trader.

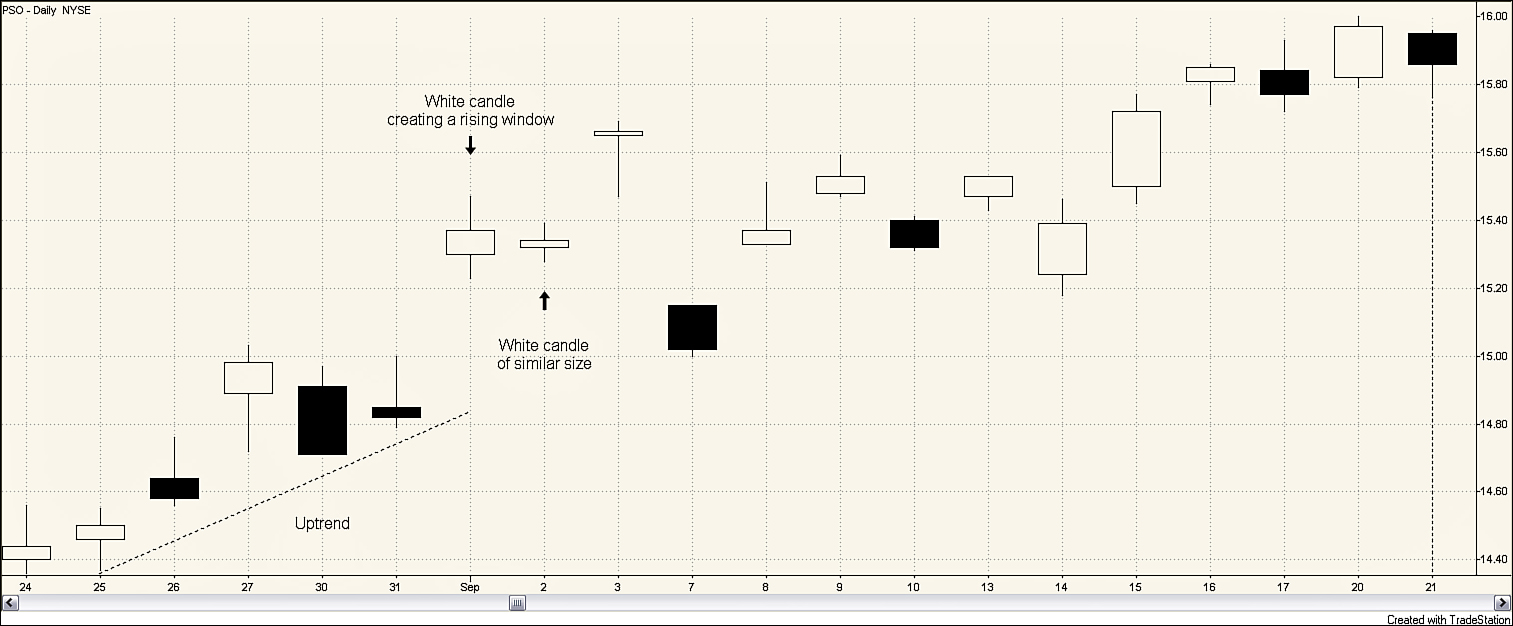

Gapping Side-by-Side White Lines

The upgap side-by-side white lines pattern is created when, during an uptrend, a window occurs with a white candle. The following session is also a white candle of similar size, with a similar open. This is a bullish continuation pattern. Again, the unclosed rising window by itself would be bullish. The two white candles reinforce this bullish signal, as shown in Figure 2.8.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 2.8. Upgap side-by-side white lines, candlestick chart for PSO, August 24–September 21, 2010

The extremely rare downgap side-by-side white lines pattern begins when a downtrend contains a falling window with a white candle, creating a down gap. The next session is also a white candle. The adjacent white candles that compose the side-by-side white lines are of similar size and similar open. Also, the second white candle cannot close the window. Because the window is a falling window, this pattern is viewed as bearish despite the existence of two white candles. The white candles are assumed to be short covering, and the downtrend is expected to continue.

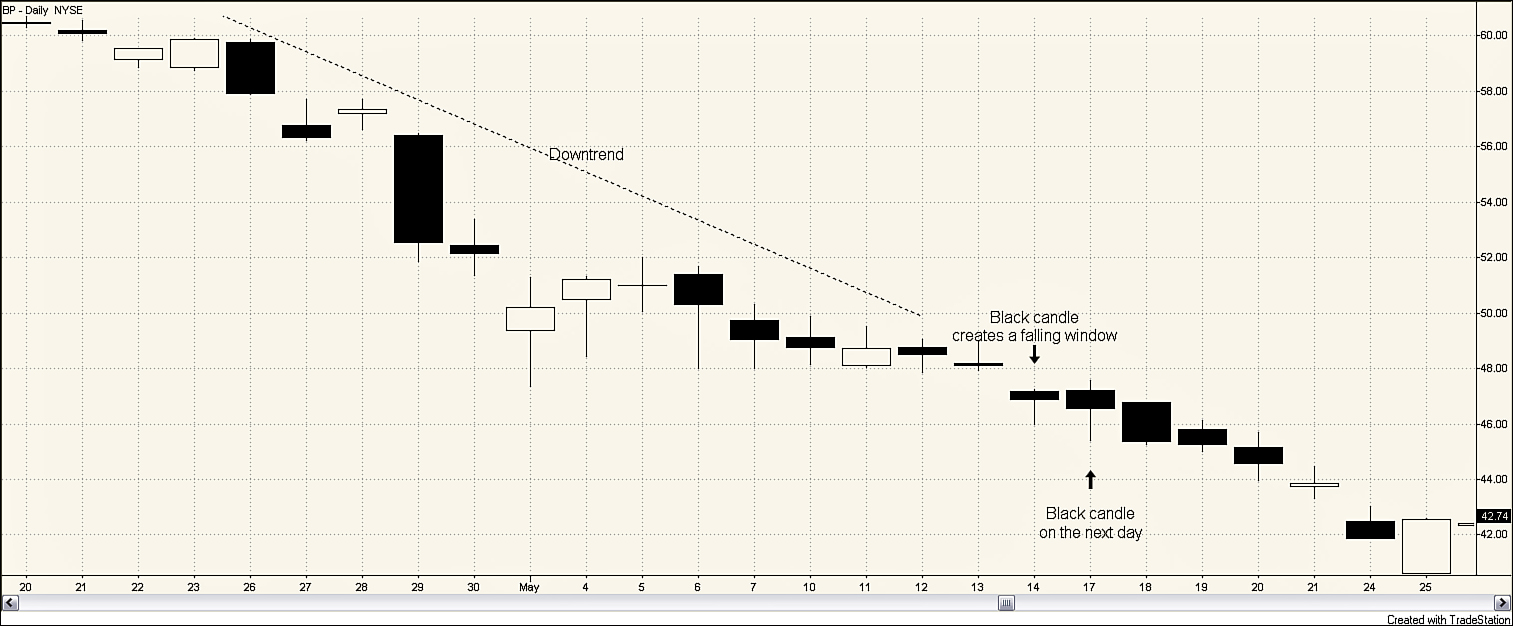

Two Black Gapping Candles

If a downside gap is followed by two black candles rather than two white candles, the pattern is known as two black gapping candles. The falling window is a bearish indicator by itself. When it is followed by two black candles, it is viewed as even more bearish.

Figure 2.9 illustrates the two black gapping candles pattern that occurred for BP in May 2010. BP was in a strong downtrend when a black candle created a falling window on May 14. The next trading day, May 17, another black candle formed; this second black candle had a similar open to the May 14 candle. As this bearish indicator would suggest, the stock price continued to fall, resulting in a decline in price of approximately 10% over the next week.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 2.9. Two black gapping candles, candlestick chart for BP, April 20–May25, 2010

Gapping Doji

The gapping doji is just what its name sounds like: a window that is created by a doji. A doji is a candle with no real body, meaning that the opening price and closing price for the session are identical. A gapping doji appearing during a downtrend is considered bearish. The gapping doji is another pattern that is rarely seen.

Although the traditional Japanese materials mention the gapping doji only in a downtrend, Nison (Beyond Candlesticks, p. 106) suggests that there is no reason to believe that the same logic would not apply to gapping dojis in uptrends. In addition, Nison recommends waiting for confirmation of a continued downtrend in the session after the window; a long, white candle that trades higher in the following session would create a bullish morning star pattern that would negate the negative signal of the gapping doji.

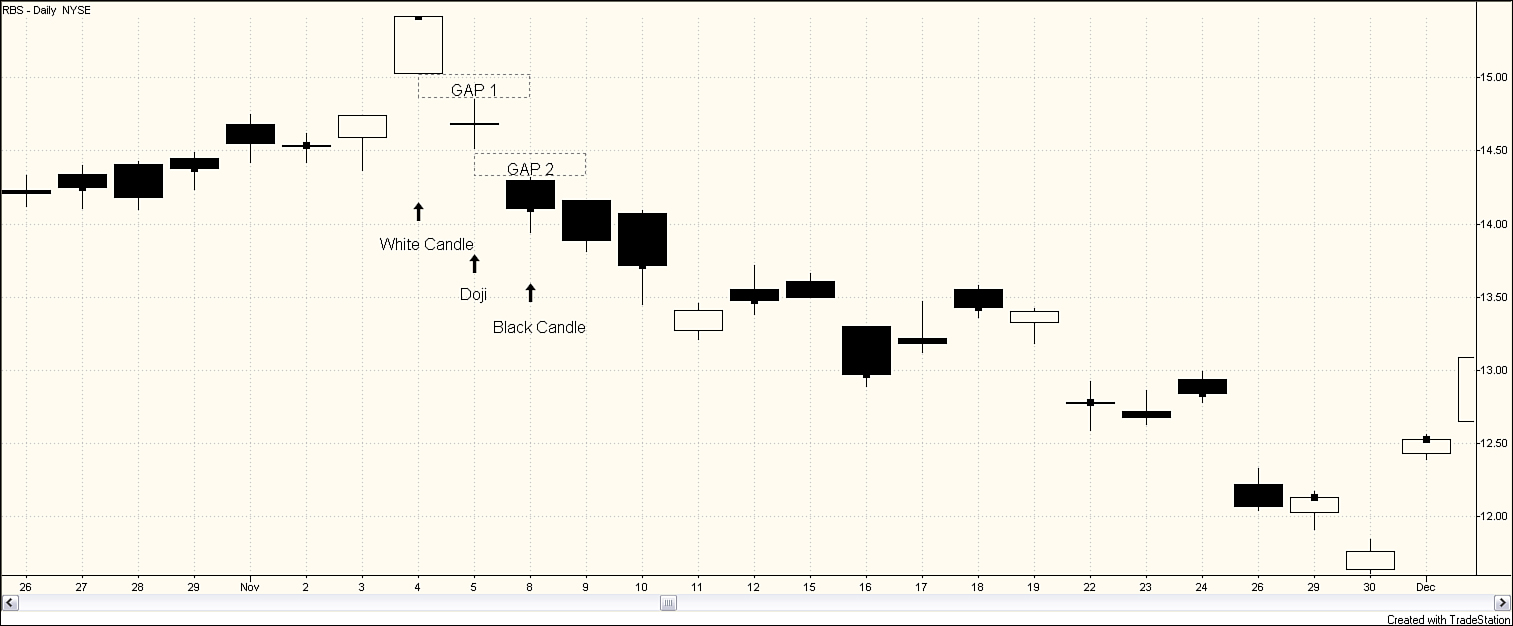

Collapsing Doji Star

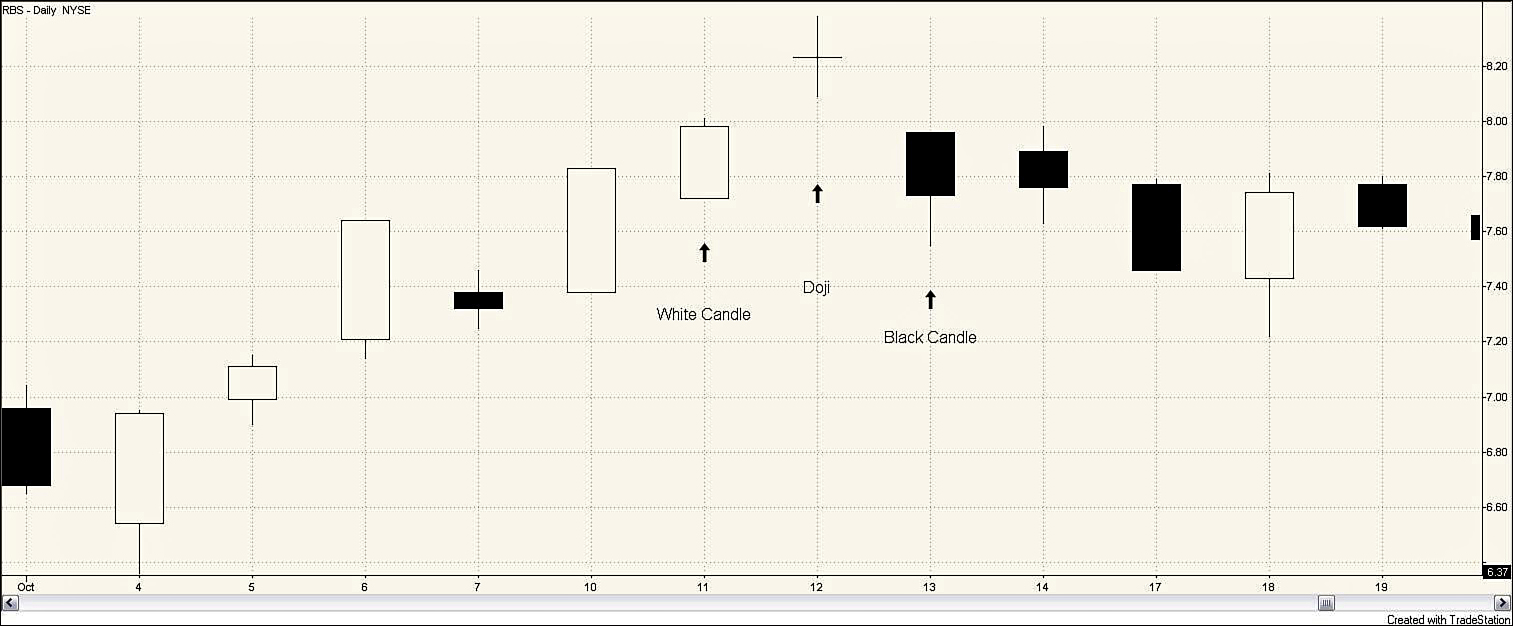

The collapsing doji star is a bearish pattern that contains two windows. It begins at a high price level as a white candle pushes the price even higher. The session after the white candle is a doji that gaps down, creating a falling window. The next session creates another falling window with a black candle. This pattern is known as the “omen of a large decline” among Japanese candlestick chartists. (Beyond Candlesticks, p. 115) A collapsing doji star occurred on November 8, 2010 for RBS stock, as shown in Figure 2.10.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 2.10. Collapsing doji star, candlestick chart for RBS, October 26–December 1, 2010

The collapsing doji star is an extremely rare pattern. We found only 89 instances of a collapsing doji star over the 30-year time period of 1982 through 2011.5 Although that averages out to approximately 3 instances of a collapsing doji star each year, you might spend a long time waiting and watching for one to occur. One occurred July 5, 1990 for Ericsson (ERIC) and another did not occur until March 8, 1996 for Tyco (TYC).

Abandoned Baby Top

The abandoned baby top is a three-candle pattern. It is a special case of an evening doji star. The evening doji star is composed of a white candle, followed by a doji with the real body lying above the real body of the white candle, followed by a black candle with the real body lying below the real body of the doji. For the abandoned baby top, the bottom shadow of the doji does not overlap the shadows of the first or third candles, resulting in two windows. These two windows are shown in Figure 2.11 for RBS.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 2.11. Abandoned baby top, candlestick chart for RBS, October 3–October 19, 2011

This top reversal signal is rare. Only 299 occurred during the study period of 1950 through 2011. However, the abandoned baby top has been more prevalent in recent years. About half of the abandoned baby tops observed over the 60-year study period were in the last decade. Twenty-three occurred in 2010 and 18 occurred in 2011, accounting for approximately 14% of the abandoned baby tops in the past 60 years.

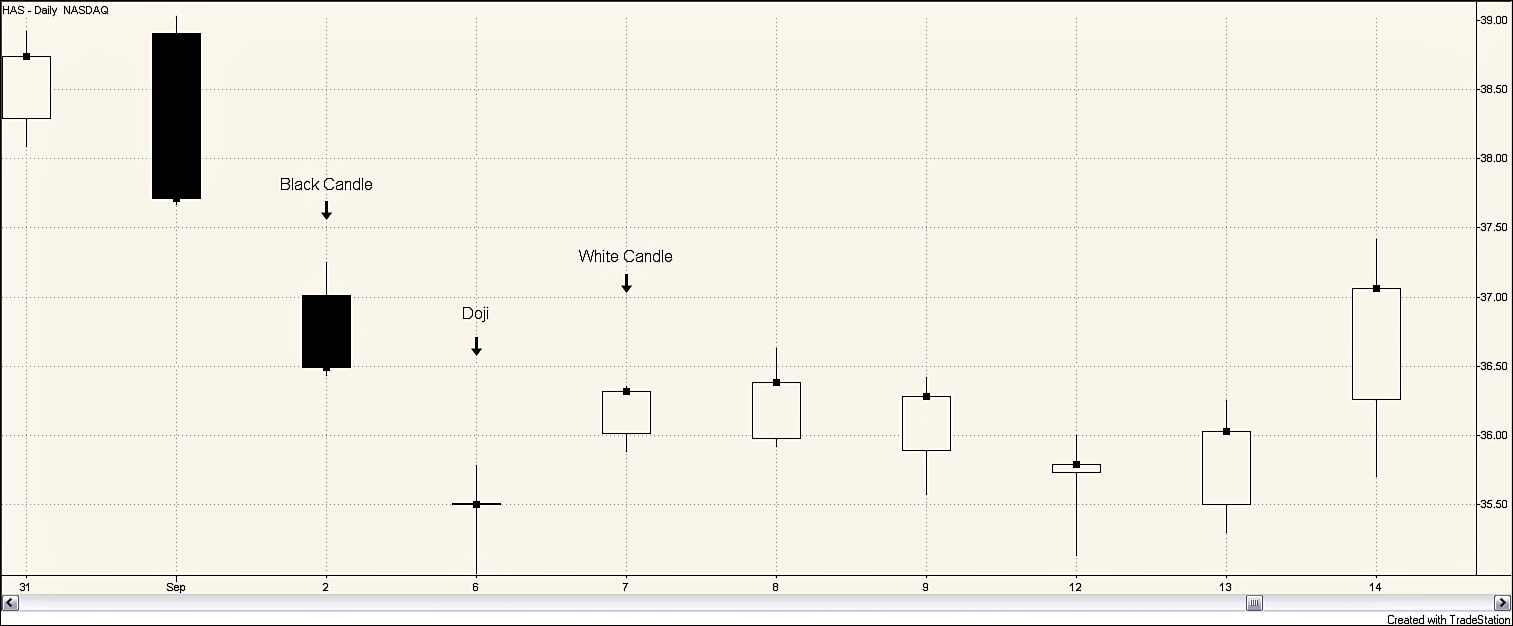

Abandoned Baby Bottom

Like the abandoned baby top, the reverse pattern, an abandoned baby bottom is extremely rare. During the 1950–2011 study period, 320 abandoned baby bottoms existed. Only two abandoned baby bottoms occurred before 1980, both in 1974. However, 16 of the abandoned baby bottoms occurred in 2010, and another 32 of the abandoned baby bottoms occurred in 2011. Thus, 15% of the abandoned baby bottoms occurring during the past 60 years have been seen in the past 2 years.

An abandoned baby bottom for Hasbro (HAS) is shown in Figure 2.12. The first candle in this pattern is black. The second candle is a doji, and the shadow of the doji lies completely below the shadow of the first candle, creating a window. The third candle is white, with the shadow completely above the shadow of the doji, creating a second window. (Nison, p. 70)

Created with TradeStation

Figure 2.12. Abandoned baby bottom, candlestick chart for HAS, August 31–September 14, 2011

Trading with Windows

Candlestick patterns are tools, not a system. The significance of many of the patterns depends upon previous price movement. To determine how meaningful a pattern is, the analyst must often consider whether it occurs during an uptrend, downtrend, or a sideways move in the market.

In addition, some of these patterns are extremely rare. The more bars included in the pattern, the more constraints put on the construction of each bar, and the more constraints put on the relative positions of the bars, the less frequent a pattern will be.

Thomas Bulkowski maintains a Web site that contains information about a number of technical patterns, including 103 candlestick patterns (www.thepatternsite.com). Searching through almost 5 million candlesticks, Bulkowski provides statistics about the frequency and performance of candlestick patterns. In general, Bulkowski’s results are not that favorable for this subset of candlestick patterns.

The best performing of the patterns containing windows is the upward gapping tasuki. The upward gapping tasuki ranks 4th among the 103 candlestick patterns, according to Bulkowski’s performance measurements. Unfortunately, this pattern is rare; Bulkowski finds only 704 instances of the upward gapping tasuki in 4.7 million candlesticks. Another pattern that performs reasonably well (9th out of 103) is the abandoned baby bottom. However, an abandoned baby bottom is even rarer than the upward gapping tasuki; the abandoned baby bottom is ranked 92 out of 103 patterns for its frequency. The collapsing doji star is even rarer; Bulkowski finds only 16 examples of the pattern. At this rate, he points out, a trader using minute bars would find a collapsing doji star only once every 3.3 years!

Bulkowski finds that the two black gapping candles pattern occurs more frequently than other window containing patterns; out of the 103 candlestick patterns he considered, the two black candles pattern is the 29th most common pattern. The pattern also ranks 10th for how well it performs relative to other candlestick patterns.

Although patterns with names such as “abandoned baby bottom” garner much attention, looking at the traditional window-containing patterns has not seemed to be exceptionally beneficial to traders. The rarity of these patterns not only means that a trader must wait a long time watching for some of them, but it also calls into question the validity of the results you see for the patterns. As you go through the remainder of the book looking at how gaps can be traded, you will encounter some of the candlestick terminology and look at some nontraditional ways that candle colors and patterns might be helpful in the development of a successful trading strategy.

Endnotes

1. Nison, Steve. Japanese Candlestick Charting Techniques. New York, NY: New York Institute of Finance, 2001.

2. The terminology of “closing a window” is used in Japanese candlestick charting in a slightly different way than “closing a gap” in traditional technical analysis. When any price movement totally fills the void on a bar chart, the gap is said to be closed. With a candlestick chart, the window is closed only if the body of a candle fills the gap. Thus, in traditional bar chart analyses, the gap in Figure 2.2 would be said to be closed on March 28. Because this chapter discusses Japanese candlestick patterns, we use the Japanese definition of closing a window when referring to gaps in this chapter.

3. Nison, Steve. Beyond Candlesticks. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1994.

4. We will examine the impact that gap size and trading volume have on trading performance in depth in future chapters. This chapter focuses on the ways in which gaps are generally viewed by those who analyze traditional candlestick chart patterns.

5. The search period begins in 1950; no collapsing dojis exist for the stocks in this study prior to 1982.