Chapter 9. Closing the Gap

The gap must be closed” is an often-heard saying among traders. This saying, however, seems to be based on lore rather than on hard evidence. The idea is that a gap creates a void in the price on a stock chart, and there is a natural tendency for market participants to want to “fill the gap” so that no visual void appears on the chart. Even those who claim that a gap must be closed differ widely in their interpretations. Some think that the gap will close quickly, within a few trading days; others talk about this occurring over a much longer time period, perhaps even years.

The criterion used throughout this book to define a gap is that one day’s price action lies totally out of the range of the previous day’s price action. Thus, for an up gap, the Day 0 low must be higher than the Day –1 high. For a down gap, the Day 0 high must be lower than the Day –1 low. In candlestick terms, the candles cannot overlap—not even the wicks of the candles. This chapter considers the closing of gaps.

What does it mean for a gap to close? Say a stock gaps up. For a gap up to close, the low of some subsequent day needs to be lower than the Day 0 high. Some gaps close quickly, whereas others may not close for very long periods of time.

Timing of Closing Gaps

As we considered how long it takes for a gap to close, some timing issues became critical, leading us to consider gaps from a shorter period of time than we had earlier in this book. Throughout this book, we considered gaps that occurred through December 2011. Looking at gaps that occurred late in the time horizon—in December 2011, for example—it is quite possible that some gaps would not close by the time of this writing but would close soon afterward. We knew that we needed to provide plenty of time after the gaps occurred to allow for closures.

We wanted to examine how long it takes for gaps to close. Many of the gaps that occurred in December 2011, for example, would not have been closed by the end of December 2011. We knew we needed to consider gaps that occurred long enough ago to allow more time for gaps to close. This, by itself, would encourage us to focus on an early period of our dataset, perhaps the earliest year of 1995. But, we wanted to stay as close to the end of 2011 as possible. As we have seen, the incidence of gaps has increased dramatically in recent years, suggesting that gapping behavior itself may be fundamentally changing. General market conditions also can have an influence on the closing of gaps. It is easier for down gaps to close than for up gaps to close when the market is trending up. Thus, looking at a fairly recent time period that was not too biased as far as an uptrend or a downtrend in the market, but which was far enough back to provide time for gaps to close, was essential.

As a compromise between the various considerations, we chose to look at gaps that occurred between January 1, 2010, and June 30, 2010. As shown in Figure 9.1, the market had several up and down moves over that time period, so it wasn’t unduly biased toward the closing of gaps in a certain direction. We stopped our computations concerning whether or not the gap closed at the end of December 2011. This gave every gap in the period at least a year-and-a-half to close.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 9.1. Daily chart for the S&P500 Index, January 5–June 30, 2010

During the January through June 2010 time period, 1,702 unique stocks experienced at least one gap. For those stocks, 10,766 gaps that met the liquidity criteria occurred. Of these 10,766 gaps, 5,373 were up gaps and 5,393 were down gaps. For up gaps, the median time to close was 5 days. For the down gaps, the median time to close was 6 days. Therefore, it appears that about half of the time gaps will close in about a week (5 trading days).

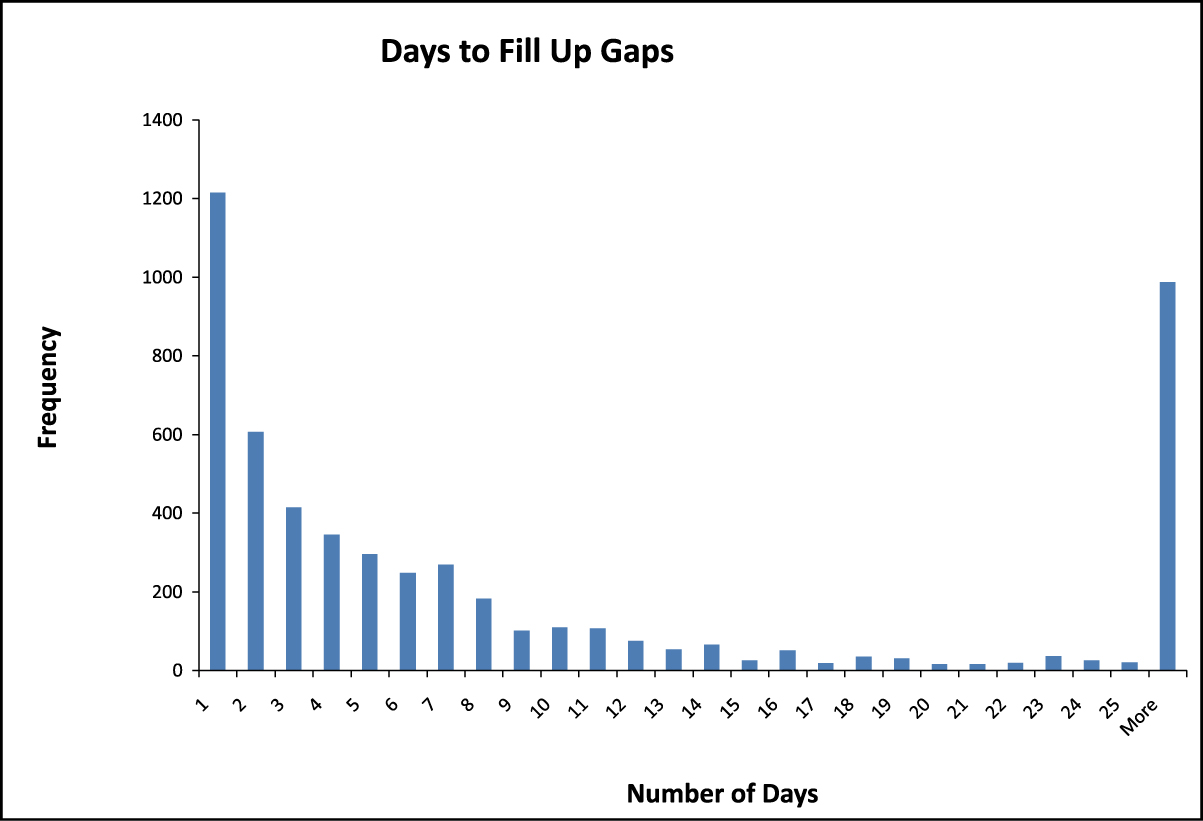

Now look at the closing of up gaps a little more closely. Figure 9.2 shows the number of up gaps that closed within 25 days of gapping. About 22.6% of the up gaps close the day after the gap. Another 11% of the up gaps close on Day 2. Thus, over one-third of the up gaps close within 2 days. Over half (53.6%) of up gaps closed by Day 5. By Day 8, two-thirds of the up gaps closed.

Figure 9.2. Number of up gaps closed by days following gap

After trading on Day 25, only 988 of the 5,373 up gaps, or 18%, had not been filled. As mentioned previously, December 30, 2011 was the cutoff date for the gaps to close. Every gap in the sample had at least one-and-a-half years to close before this cut-off date; gaps that occurred earlier in 2010 had even longer. By the end of 2011, 216 of the up gaps had still not closed. Thus, about 4% of the up gaps had not closed within at least 18 months. For example, the Crocs Inc. (CROX) up gap on January 4, 2010 at approximately $5 a share had still not closed by the end of 2011. The closing price at the end of the year was $14.77, which meant that it still needed to drop almost $9 more to close the gap that occurred almost 2 years before.

In Chapter 2, “Windows on Candlestick Charts,” you considered some of the ways in which gaps were used by those practicing traditional Japanese candlestick charting. One of the rules of thumb followed by these practitioners is that if a gap is not closed within 3 days, the market probably has enough power to continue its trend for 13 more sessions. How does this mesh with what you see for the closing of up gaps in Figure 9.2? You do indeed see that many up gaps, more than 40%, close within 3 days. In the sample, 3,136 gaps remained unfilled after 3 days. Did these up gaps tend to have enough power for a trend in the direction of the gap to continue for 13 more trading days? We see that by Day 11 (8 days after the suggested 3-day observation period), 1,657 of the 3,136 gaps that remained on Day 3 had been filled. Over half of the gaps that had not been closed by Day 3 had been filled by Day 11. Because this is only 8 days after the suggested 3-day watch period, the idea that the unclosed up gap has the momentum to continue in an uptrend for 13 more sessions is not supported.1

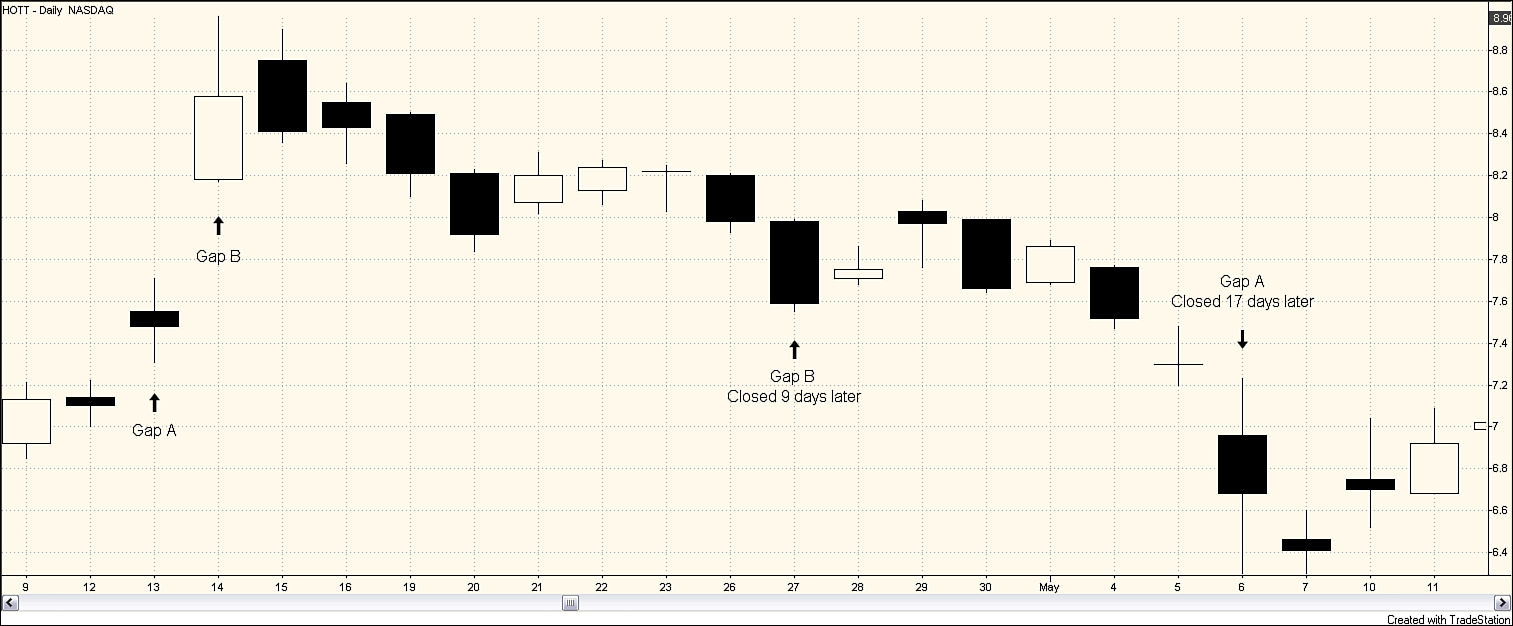

You must also be careful not to conclude that because a gap has not closed that a trend in the direction of the gap is continuing. Look at the two up gaps shown for Hot Topic, Inc. (HOTT) in Figure 9.3. HOTT gapped up on April 13, 2011, and again the following day. The April 13 gap, labeled Gap A in the figure, did not close until 17 days later. The April 14 gap, labeled Gap B, closed 9 days after it occurred. Gap A is an example of a gap that did not close in 3 days and continued to be open for 13 more trading days. However, price was not trending upward in the direction of the gap; price was slowly falling to close the gap.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 9.3. Daily stock chart for HOTT, April 9–May 11, 2011

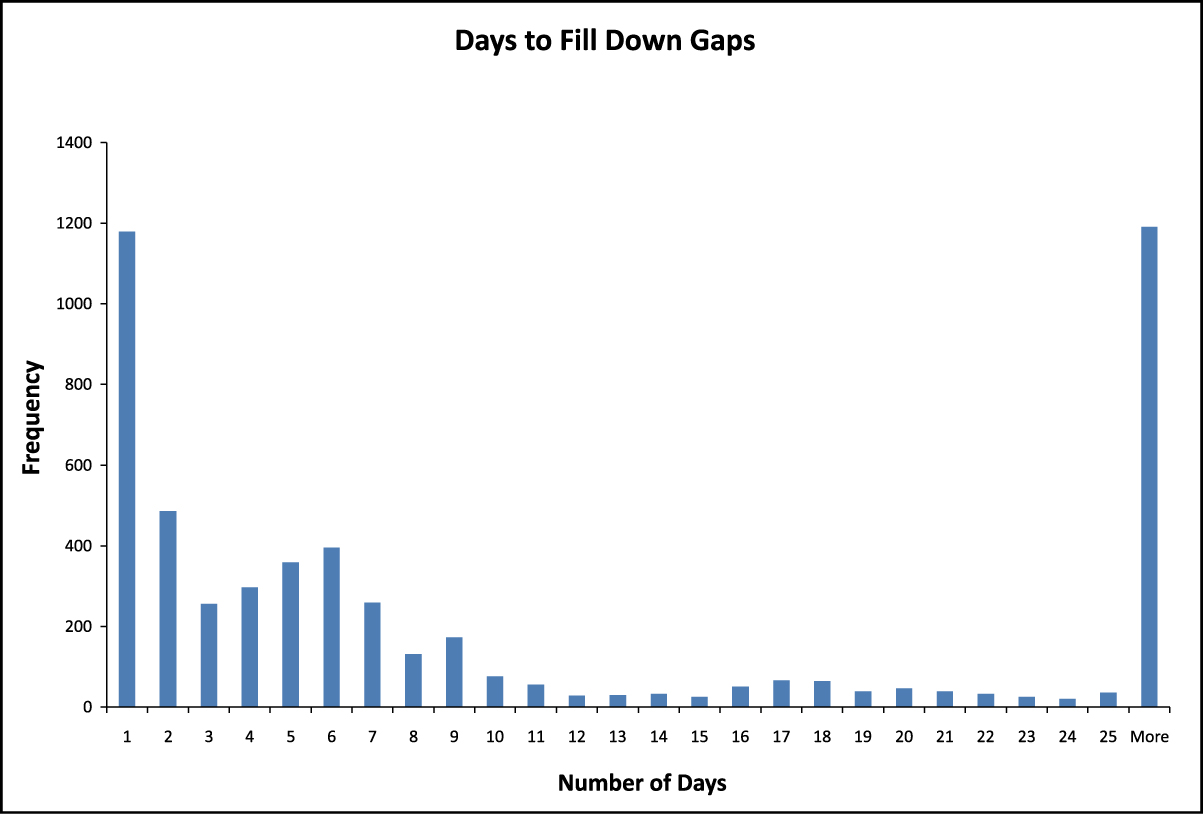

Now turn your attention to the closing of down gaps; information about these down gaps is provided in Figure 9.4. Almost 22% of down gaps close the following day. By Day 3, close to 36% of down gaps have closed. By Day 6, 55% of the down gaps have closed. Two-thirds of all the down gaps have closed by Day 11, and three-quarters have filled by Day 20.

Figure 9.4. Number of down gaps closed by days following gap

Of the 5,393 down gaps, 1,191 remain open after 25 days of trading. Of these 1,191 gaps, 173 remained unclosed by the end of 2011. Thus, of all the down gaps, a little more than 3% remained unfilled over one-and-a-half years later. An example of an unfilled down gap would be the gap occurring for Monsanto (MON) on January 12, 2010 at $83 per share. At the end of 2011, almost 2 years later, MON was trading in the $72 range, and the gap remained unfilled.

What about the rule of thumb or waiting 3 days to see if a gap remains unfilled to confirm a trend in price? After the closing on Day 3, 3,472 gaps remained unfilled. By Day 11, 8 days later, more than half of those unfilled gaps were closed. Thus, if a gap remains at Day 3, chances are it will be closed by Day 11. Again, this evidence does not support the notion that the failure of a gap to close within 3 days suggests that a trend in the direction of the gap will continue for 13 more days.

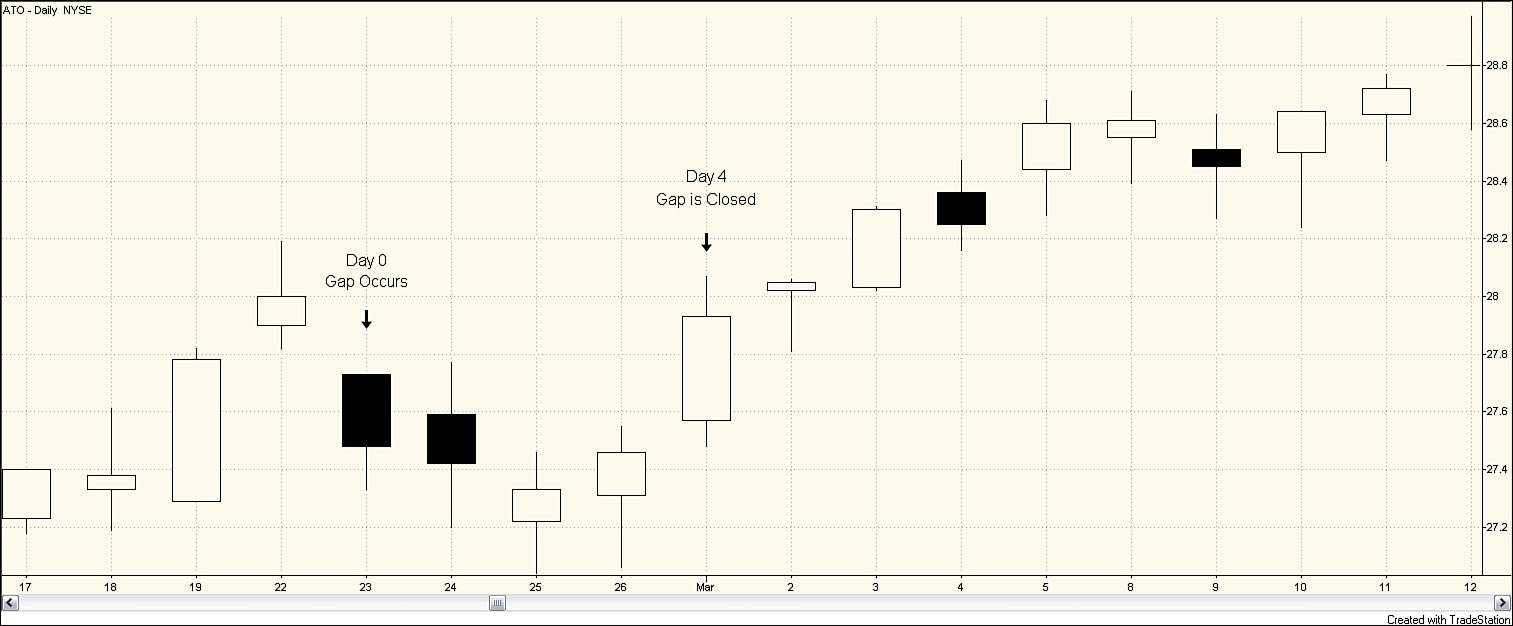

Figure 9.5 shows an example of a gap that closed quickly. On February 23, 2011, Atmos Energy Corporation (ATO) gapped down, but the gap closed in 4 days, which is slightly faster than the median of 5 days.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 9.5. Daily stock chart for ATO, February 17–March 12, 2010

For an example of a gap that is much slower to close, look at the February 28, 2010 gap for Jack in the Box (JACK) in Figure 9.6. This gap was not filled until June 24, 83 trading day later.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 9.6. Daily stock chart for JACK, February 22–July 2, 2010

Concluding Comments about Closing the Gap

As we have talked to a number of traders, the most frequent question about gaps is, “Doesn’t a gap always close?” Based on the calculations, it appears that gaps may tend to close in roughly one trading week (5 days). For the sample of 10,766 gaps during the period January 1 to June 30, 2010, the median time to close for up gaps was 5 days, whereas the median time for down gaps to close was 6 days. Some of the gaps observed had still not closed more than 1½ years later.

Throughout this book, gaps have been discussed using daily bars. Sometimes a stock opens above the previous day’s high or opens below the previous day’s low, but subsequent price movement during the day causes the stock to not meet the criteria for a gap. This price behavior creates a gap on intraday charts but not on daily bar charts. Often, this is referred to as an “opening gap” because it creates a gap at the opening of the trading day, but it is filled within the day.

We have not done an exhaustive study of opening gaps. Because we have received so many questions regarding these gaps, we thought it would be helpful to mention something about the frequency of their occurrence. Of the 1,702 stocks considered in this chapter that did gap during the January–June 2010 time frame, 52,616 opening gaps occurred. Of these, 12,746 were not filled during the day. So approximately 76% of the opening gaps closed on the day they occurred, and about 24% became actual gaps. However, not all those 12,746 met the liquidity criteria; 10,779 of these gaps did meet the liquidity criteria and were included in the results in previous chapters.

Although this chapter presents some interesting information about price behavior around gaps, it hasn’t led to any particular trading recommendations. A detailed study of this topic might lead to some intriguing trading possibilities, but it’s also something that is not easily done. We may explore it in the future.

Endnotes

1. An important note is that the Japanese candlestick tradition is based on the notion that a “window is closed” rather than the author’s idea of a gap closing. As explained in Chapter 2, in the Japanese tradition a window is closed only if the real body of a candle closes past the window. For the authors’ analysis, if price fills the void intraday, the gap is considered closed. Therefore, a broader definition is used for the closing of a gap and a gap is considered closed when a Japanese candlestick analyst would still consider the window opened.