Chapter 8. Gaps and the Market

This chapter analyzes gaps in relation to overall market movement. Some days have an extremely high number of gaps. The gaps on these high gap days are tipped heavily in one direction. For example, there might be 599 gaps on one day, with all but 3 of them being up gaps. Does this situation point you toward certain trading strategies? Does it give you a clue as to which direction the market might be headed? A different question related to market movements is: Should prior market movements alter your interpretation of individual stock gaps? For example, is there a difference in how you might interpret a gap down for a stock if the market is already trending down? These are some of the questions this chapter explores.

High Gap Days

First consider the issue of the total number of gaps occurring in the market on a given day. The total number of gaps in a given day can vary greatly. The distribution is not uniform across time. On some days, more than 500 stocks gap. Of those 500, all might be down gaps. Or the vast majority may be down gaps. The same is true for up gaps. Do these dominant direction high gap days give you any clue about future market direction?

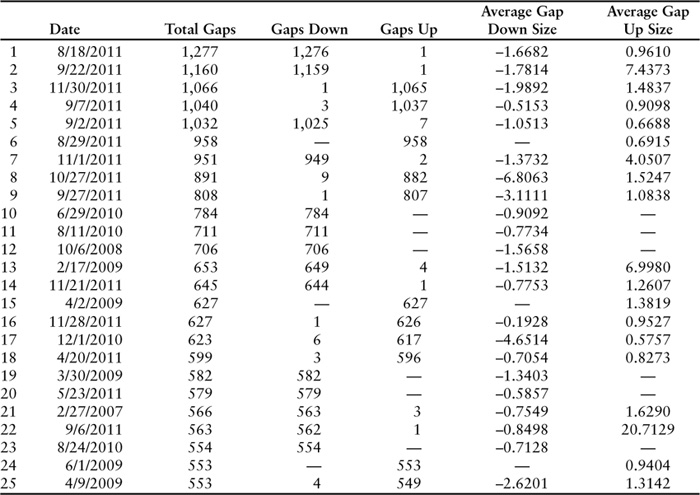

Table 8.1 shows the 25 days in our study that had the most total gaps. The table shows the date, total gaps, the breakdown of down versus up gaps, and the average size of the gaps. As can be seen, there were 25 days on which 553 or more gaps occurred. Nine of those days had gaps only in one direction. The remaining 16 days had less than 10 gaps in the opposite direction from the majority. You might expect to see such a one-sided split if the average gap size were quite large, but that is not the case. For example, on December 1, 2010, the average gap up size was only 0.576%, but there were 617 up gaps and only six stocks that gapped down. The largest average gap in this list for the majority side was –1.781% on September 22, 2011.

Table 8.1. Days with the Greatest Number of Gaps

In looking at the list, something striking jumps out. Fourteen of the 25 days with the largest number of gaps occurred in 2011. Actually, nine of the top ten in the list occurred in 2011; furthermore, these nine occurred during the months of September–November 2011. This raises some interesting questions. In Chapter 3, “The Occurrence of Gaps,” you saw that the total number of gaps in a year has been rising steadily. So is the fact that so many of the high gap days occurred in 2011 just a consequence of increased gap activity over time? Digging further, you can see that the earliest date in the list is February 27, 2007. That gaps have been occurring more frequently over time is a factor, however it goes beyond that simple explanation; 2011 was an especially turbulent year in several respects.

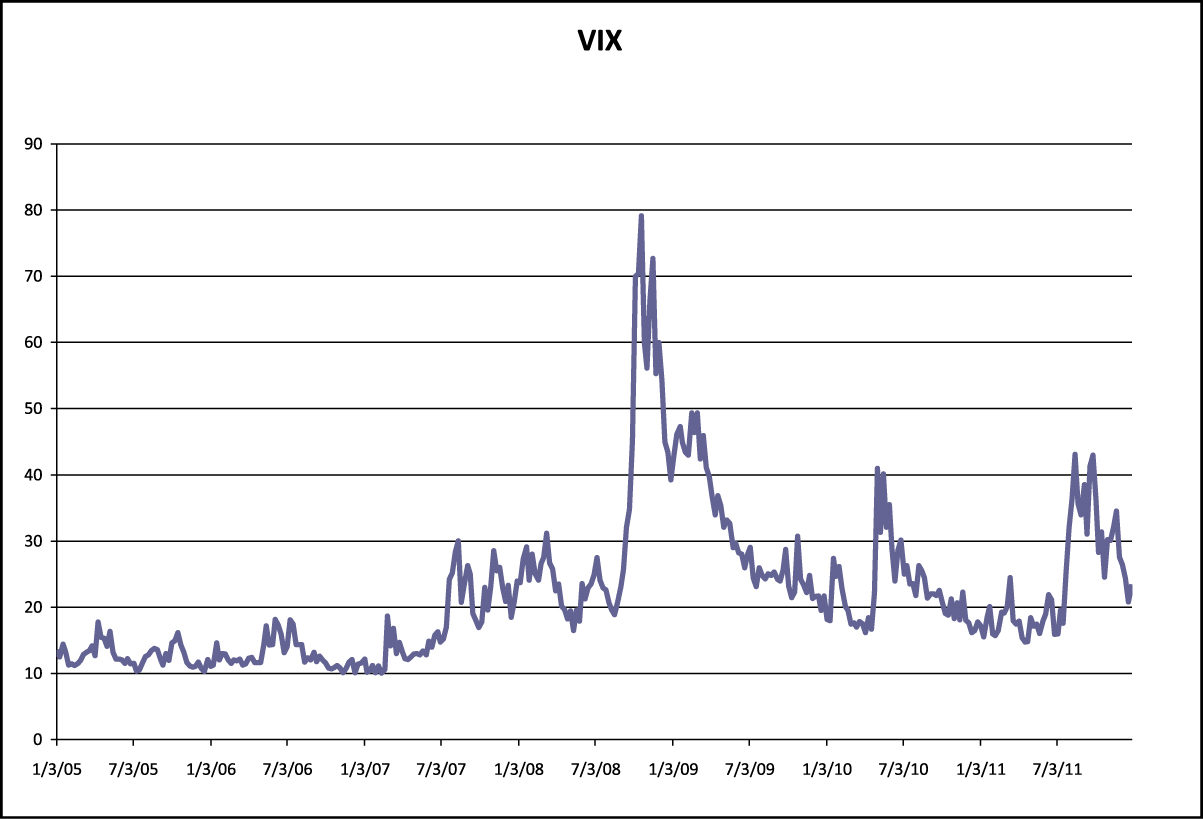

One way that market volatility is measured is the VIX. The VIX is an index of volatility for the S&P 500 index. Figure 8.1 shows a graph of the VIX over the 2005–2011 time period. During this period the value of the VIX exceeded a level of 40 during three subperiods: October 2008–April 2009, May–July 2010, and August–October 2011. Twelve of the 25 days with the largest number of gaps in Table 8.1 occurred during these three subperiods; 7 of those days (about one-third of the high gap days) occurred during the August– October 2011 period.

Figure 8.1. Volatility as measured by the VIX, 2005–2011

However, just looking at the VIX doesn’t tell you what is behind the volatility; it simply measures the volatility. To investigate at a deeper level what might be behind the price movement on these particular days, consider the news on these 25 days. A summary of events occurring on those days is provided on the following pages.

There is an old maxim that says “what goes around comes around.” The Austrian statesman Prince Metternich once said “When Paris sneezes, Europe catches a cold”—or at least something quite similar. (There is some dispute about the exact quote.) This quote was later altered by many to be “When the U.S. sneezes, the world catches a cold.” However, looking at the preceding international relationships, something such as “When Europe or Asia sneezes, the United States catches a cold” may now be more appropriate.

Looking at the high gap days chronologically highlights the clustering of these days within the August through November 2011 time period. Figure 8.3 shows that four of these high gap days occurred within the 7-day trading period of August 29–September 7, 2011. Monday, August 29, was a high up gap day and the S&P500 index rose. On each of the following 2 days, the S&P500 index rose slightly. Thursday’s decline in the S&P500 erased those gains. Then, on Friday, September 2, a high gap down day occurred. The S&P500 dropped, more than erasing Monday’s gains, leaving the S&P500 down slightly for the week. The next 3 days were Labor Day weekend, so Tuesday, September 6, was the next trading day. On Tuesday the S&P500 experienced another down move and 562 stocks gapped down. After 2 consecutive high down gap trading days, a high up gap day occurred on Wednesday, September 7.

You might think that 4 high gap trading days clustered so close together would indicate some major movement in the market. However, Figure 8.1 tells a different story. The S&P500 dropped approximately 14% over the July 25–August 8 time frame and then entered a congestion area. The frequent high gap days were representative of market indecision and the battle between buyers and sellers was more than a push of the market in a particular direction.

On days with a large number of gaps, it would seem reasonable that there might also have been gaps in some of the major market indexes. However, that is not necessarily the case. Figure 8.2 shows the behavior of the S&P 500 Index and SPY over the latter part of 2011. The chart shows many examples of gaps in SPY, but the index itself only gapped on 2 days: September 22, 2011 and November 1, 2011. The S&P 500 ETF (ticker SPY) tracks the S&P. This shows that sometimes even with gaps in a large proportion of the index component stocks, the index or index-based ETF may not gap.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 8.2. Daily chart for the S&P500 Index, July 25–November 15, 2011

Created with TradeStation

Figure 8.3. Daily chart for the S&P500 Index ($INX) and SPY, August 1–November 23, 2011

Trading High Gap Days

What types of trading opportunities might these large gap days present? Three possible approaches are discussed. First, high gap days might provide some type of market timing signal. For example, if an investor observed a large number of up gaps on a given day, he might buy shares of SPY, with the hope that the S&P 500 Index was headed up. This would be taking a continuation approach. Alternatively, he could sell SPY, counting on a reversal. With either approach the investor would be looking to the large number of gaps as a signal regarding future market direction. A second approach would be to buy or sell some of the stocks that were part of the group of stocks gapping in the same direction. This could be done either with a continuation or a reversal outlook, so it would be similar to the first approach, but trading the individual stocks rather than an index-based ETF. A third approach would be to buy or sell the few stocks that gapped in the opposite direction from the pack. If 562 stocks gapped down and only one gapped up, surely there is something unusual with that stock that may or may not present a trading opportunity. Now examine all three possible approaches.

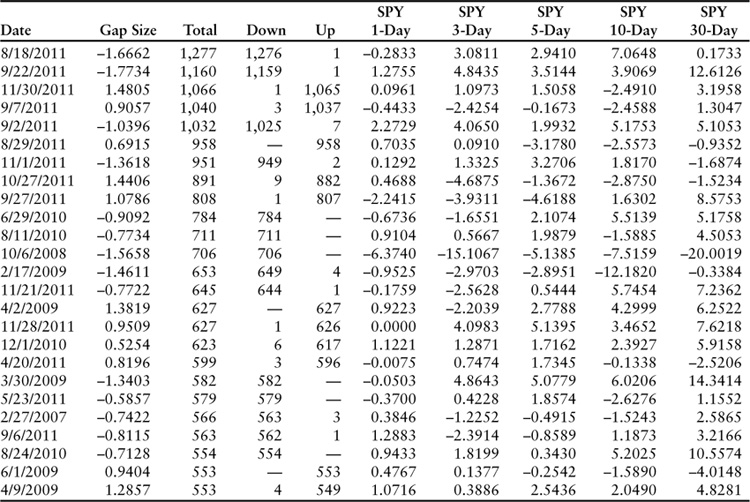

Begin by examining the first approach, which uses the high gap days as a market timing signal. Table 8.2 shows the returns on SPY, the S&P 500-based ETF, over various subsequent periods. These returns were calculated using the same basic procedure as that used for individual stock gaps. The n-day return assumes that SPY was purchased at the opening price on the day after the gap and then sold at the close on day n. It appears that these high gap days do not necessarily provide useful trading signals. Furthermore, that is true whether you consider a continuation approach or a reversal approach.

Table 8.2. Returns on SPY after High Gap Days

A reversal approach would have worked well using a 5-day holding period immediately after the gap date for the 6 days with the largest number of down gaps. The 5-day returns for these gaps (8/18/11, 9/22/11, 9/2/11, 11/1/11, 6/29/10, and 8/11/10) were 2.94%, 3.51%, 1.99%, 3.27%, 2.11%, and 1.99%, respectively. However, the 5-day return following the 10/6/08 gap, which was the day with the next highest number of gaps, was –5.14% (the 3-day return was –15.11%). There were 14 high down gap days in Table 8.2. The average 5-day return for a reversal strategy following these 14 days was 1.02%, which is quite good. In addition, the return was positive for 10 of the 14 instances. These results might lead you to the idea that a reversal strategy following the high gap days would be the way to approach things.

However, looking at the 11 days with a high number of up gaps might make you pause. The average 5-day return for a reversal strategy in this case would have been –0.53%. A reversal strategy (using a 5-day holding period) would have been profitable for only 4 out of the 11 instances. What if you took a long position after every high gap day, regardless of gap direction? The average 5-day return was 0.80%, which annualized is more than 40%. However, ignoring the gap direction seems rather odd. Twenty-five observations is not a big sample and the variability in the results is quite high.

Is there any reliable strategy for using these high gap days to time the market as a whole? If there is, the authors didn’t see it. But, that certainly doesn’t mean that it’s not there. The high gap days are definitely intriguing. Intuitively you would think that they must contain some valuable information about future market direction.

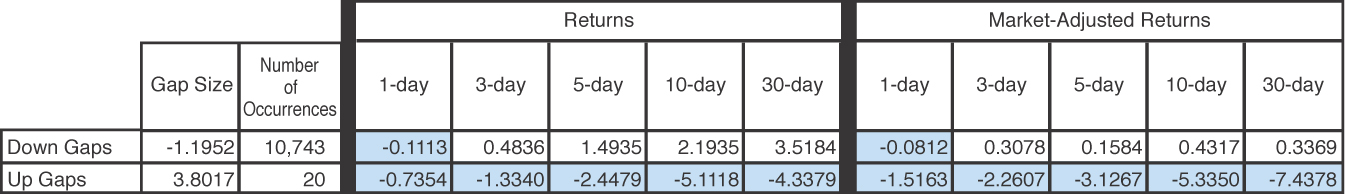

A second approach would be to buy or sell some of the individual stocks that are part of the large group of stocks gapping in the same direction. Table 8.3 addresses this approach. First consider the days with a high number of down gaps. The 1-day return (both unadjusted and market-adjusted) is negative for the stocks that gapped down. But, the 3, 5, 10, and 30 returns are all positive. The trading idea would be to perhaps go short on the down-gapping stocks on the day after the gap, looking for a downward continuation. But, after Day 1 it appears that it would be better to be long, hoping for a reversal. The magnitude of the returns is quite high, which is certainly intriguing.

Table 8.3. Returns for Stocks That Gap on High Down Gap Days

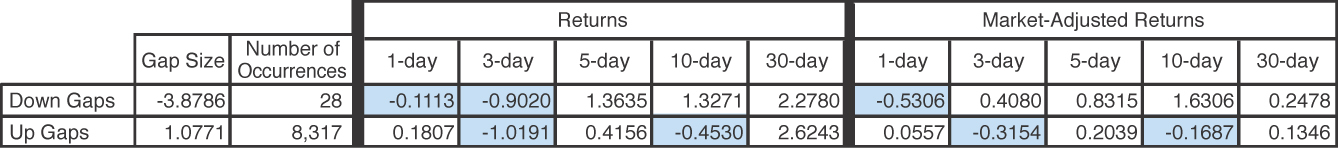

In Table 8.4 most of the stocks are gapping up. Here a possible trading strategy is not as clear. On the day after the gap, it looks like a continuation strategy would be best because the 1-day returns on the up-gapping stocks are positive. But, after Day 1 the stocks, on average, reverse direction, which would mean switching to a reversal strategy. For the down gap strategy, all the returns after Day 1 were the same sign, positive. However, that is not true for the up gaps. Some of the 5-, 10-, and 30-day returns are positive and some are negative. The reversal approach looks attractive between Days 1 and 3, but past that it’s hard to say.

Table 8.4. Returns for Stocks That Gap on High Up Gap Days

A third approach is to trade the stocks that are gapping in the opposite direction. Surely there must be something unusual about that stock or small group of stocks. To examine this possibility dig into the details of the stocks in Table 8.3 that fought the herd. The returns for the stocks that gapped up when almost all the rest were gapping down are quite intriguing. All ten return numbers across the row are negative and the returns increase in magnitude as the holding period increases. A reversal strategy, going short on the stocks that gap, looks attractive. But the sample size is small; there are only 20 observations.

Looking at the down-gapping stocks, when large numbers are gapping up, the returns (refer to Table 8.4) for the first few days are negative. After Day 3 though, they turn positive. This would suggest that initially a continuation strategy might be best, but that price may reverse direction fairly soon. The sample size here is still small, only 28.

The number of stocks bucking the trend on the high gap days is small, but the stocks appear to present interesting trading opportunities when they do occur. It can be worthwhile to drill down to a deeper level, trying to understand what happens in these situations. Therefore, consider some of the specific circumstances concerning the stocks that move counter to the rest of the pack on high gap days.

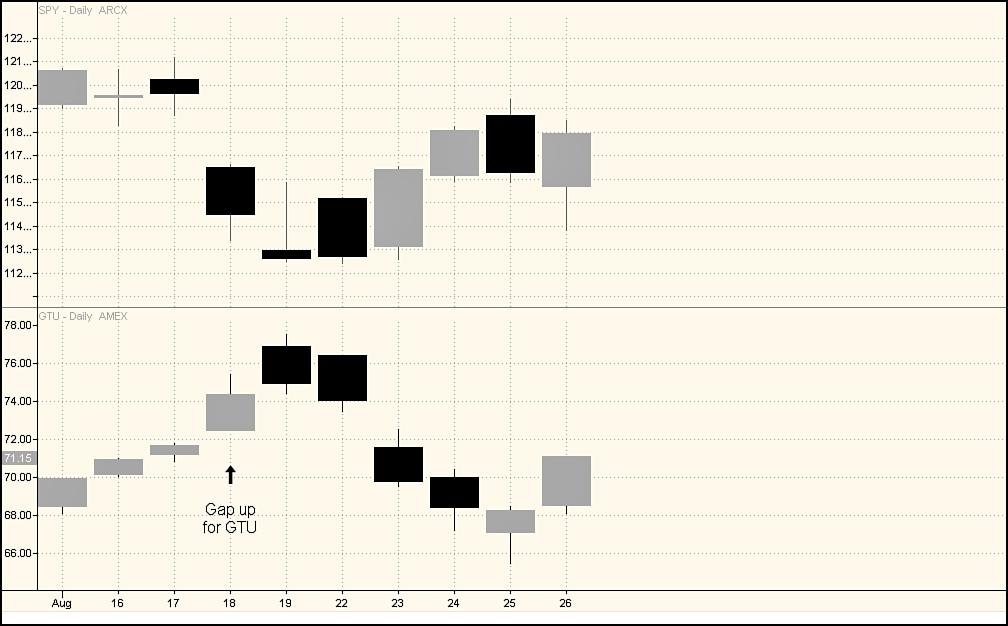

Only one stock gapped up on August 18, 2011 whereas 1,276 gapped down: Central Gold Trust (GTU), which is a Canadian company that invests primarily in gold bullion. As you just saw, not only did a record number of stocks gap down on August 18, but also the DJIA dropped more than 400 points amid global economic concerns. Because many investors turn to gold—wanting hard assets rather than financial assets—when they are nervous, it makes sense that this stock had a good day on August 18. As shown in Figure 8.4, GTU continued moving up during part of the day on the 19th but closed down on the 19th and the following 3 trading days (August 22, 23, and 24). As part of its downward move, GTU had a large down gap on August 23. How did GTU’s move compare to the overall market those next few days? SPY continued moving down on August 19 and 22 but turned up fairly strongly on the 23rd, closing higher on the 23rd and 24th.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 8.4. Daily chart of GTU and SPY, August 15–24, 2011

On September 22, 2011, only one stock gapped up, swimming against the tide as 1,179 stocks gapped down. The stock was Goodrich Corporation (GR), which is in the aerospace/defense industry. Here, as you can see in Figure 8.5, the story actually begins before September 22. On September 16, GR moved up more than 7% on rumors (that were reported in The New York Times that evening) that the company might be taken over by United Technologies. Over the next 3 days (September 19, 20, and 21), it continued to move up, rising from a close of 92.89 on the September 16 to a close of 109.49 on September 21. The large gap up (7.44%) on September 22 was driven by the announcement that United Technologies had agreed to buy GR. It closed at 120.60 on September 22 and finished the year at $123.70.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 8.5. Daily stock chart for GR, August 13–December 31, 2011

Omnivision Technologies, Inc. (OVTI) was the only stock that gapped down on November 30, 2011. The drop followed the release of its latest quarterly financials, which the market found disappointing. The same thing had happened the previous quarter when the stock gapped down on August 26, resulting in a price drop of 30% in one day. You can see in Figure 8.6 that OVTI’s high was slightly more than 35 on July 1. On November 30, the low for the day was 10.15, quite a drop in just five months. The 5-day return after November 30 was 18.4%. There was a good opportunity to make money by betting on a short-term reversal and going long OVTI at the open on Thursday, December 1, but the opportunity probably would have been difficult to foresee.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 8.6. Daily stock chart for OTVI, July 1–December 23, 2011

The three stocks that gapped down on September 7, 2011 (Darden Restaurant [DRI], Frontier Communication [FTR], and Novagold Resources [NG]) all continued moving down the following day. The 10-day return on all three was negative, but DRI and FTR did come back up some before continuing down. The best of the three to short would have been NG. Looking at Figure 8.7, the day of the gap was not a huge attention getter by itself. However, consider the context in which this gap occurred. The two previous trading days, September 2 and September 6, NG had two relatively tall white candles. Remember that those two trading days were number 3 and number 13, respectively, on a list of days with the largest number of down gaps. Thus, NG’s rise on September 2 and 6 occurred against an extremely bearish market background. Then, on September 7, the market moved higher with 1,037 gap ups, the second largest number in the study. As one of only three stocks that gapped down that day, NG was definitely swimming against the tide.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 8.7. Daily stock chart for NG, June 6–November 1, 2011

A trader shorting NG at the open on September 8 would have enjoyed a nice profit as the stock continued down, punching through support at about 8.60. The 10-day return would have been 28.77%. On Day 11, another gap down occurred, and a short position would have continued to be profitable as the stock dropped steadily, finally bottoming just below 6 on October 4.

Unlike NG, FTR fell on September 2 and September 6 along with the broader market. Instead of rebounding on September 7 as much of the rest of the market did, however, FTR gapped down. An investor who, thinking this downtrend would continue, went short at the open on September 8, would have had a profit by Day 10. As shown in Figure 8.8, FTR continued in a downtrend through the end of 2011.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 8.8. Daily stock chart for FTR, September 24–December 31, 2011

The third stock to gap down on September 7, DRI (see Figure 8.9), had also fallen the two previous days along with the broader market. DRI was one of the 1,025 stocks that gapped down on September 2. Unlike the broader market, DRI did not recover on September 7; instead it gapped down again. Investors who shorted DRI at the open on September 8 would have positive 1-, 3-, 5-, and 10-day returns, although the stock was in a trading range for the rest of 2011.

Created with TradeStation

Figure 8.9. Daily stock chart for DRI, July 13–November 18, 2011

September 2, 2011 was an interesting day. Seven stocks gapped up that day whereas 1,025 went the other direction. The seven were Endeavour Silver Corporation (EXK), Finisar Corporation (FNSR), MineFinders Corporation (MFN), Newmont Mining Corporation (NEM), Sprott Physical Silver Trust (PSLV), Royal Gold Inc. (RGLD), and Silver Wheaton Corporation (SLW). Six of the seven stocks are related to gold or silver in some manner. The short term price behavior of this group was not consistent; however the average 30-day return was –16.89%. Because the market went up some over that same period, the adjusted return of –21.99% was even better (for those in a short position). These results suggest that precious metal stocks may warrant special attention on days with a high number of gaps.

There were only two stocks that gapped up on November 1, 2011, whereas almost a thousand gapped down. The case of ITT Corporation (ITT) on that day was unusual. Reverse splits are not too common, but ITT underwent a 1:2 reverse split on that day. In addition to the split, ITT shareholders of record as of October 17 also received one share of Exelis Inc. (XLS) and one share of Xylem Inc. (XLY) on October 31. The ex-distribution date for the distribution and the reverse split was November 1. The two other stocks that gapped up on the November 1 were Leap Wireless International Inc. (LEAP) and (VRUS).

We have discussed the specific stocks that for the seven days with the highest number of gaps were gapping counter to the crowd, going through things day by day. What are some of the common factors that caused stocks to go in the opposite direction from the rest of the crowd?

One common cause for gaps is reaction to earnings reports. On October 27, 2011, only 9 stocks gapped down whereas 882 gapped up. Of the 9 stocks gapping down, 8 of the gaps were negative reactions to earnings reports. Similarly, on April 20, 2011, only 3 stocks gapped down, all on disappointing earnings reports.

Many gaps are related to merger and acquisition activity, as previously discussed in Chapter 3. A good example of how a stock’s price may exhibit some wild gyrations around a hostile takeover bid occurred during June–September, 2011, with Temple-Inland (TIN). On September 6, 2011, while 562 stocks gapped down that day, Temple-Inland (TIN) was the lone stock to gap up. News that International Paper had finally reached an agreement with Temple-Inland after increasing its previous bid to $32 per share sent the shares up by about 25% to a close of 30.85. However, the fireworks had started earlier. TIN had previously gapped up by approximately 40% to near $30 on June 7. The news that drove that upward price jump was unusual. TIN had adopted a poison pill defense in an attempt to fend off a hostile takeover by International Paper. On August 18, TIN gapped down along with 1,286 other stocks, losing approximately 7% of its value. That move took the price back down below $26. But another big down gap was still just slightly up ahead. On August 23, TIN dropped another 14%, closing at 21.33. The price even went as low as 19.03 at one point during that day. This drop in price came from another direction. TIN was sued over the 2009 failure of a Texas bank that it had spun off in 2007. So in the space of just 3 months, TIN had experienced two up gaps, each more than 25%, and two down gaps, each more than 7%.

There is plenty of evidence that the market usually reacts negatively whenever a company issues more stock. On September 27, 2011, Coffee Holding Company (JVA) gapped down and closed down by 15.6% whereas 807 other stocks gapped up. JVA had moved down in response to an announcement that the company had entered into an agreement with some institutional investors to sell 890,000 units that consisted of one share of common stock per unit and three-tenths of a warrant for one share of common stock. Similarly, on April 9, 2009, the market reacted negatively to Equity One’s (EQY) announcement that it was selling additional stock to raise cash. The market also did not like Omnicare’s (OCR) announcement on December 1, 2010, that it was raising money by issuing some Convertible Senior Secured Notes. This caused the stock to gap down, closing down by 3.6% (issuing notes is less distasteful to investors), whereas 617 other stocks gapped up.

Most of the events that caused some stocks to move opposite to the pack on the 25 days with the largest number of gaps have been discussed. As you saw, there is usually some significant piece of news that is the cause. Now return to the question: Do stocks that go against the rest of the herd offer tradable opportunities? In general, probably not. Although there are certain common causes (earnings announcements, takeovers, issuance of securities, and so on) each case is unique. Price moves subsequent to the gaps can be large. The overall averages in Tables 8.3 and 8.4 look intriguing, but approach with caution. These types of gaps probably warrant investigation on a case by case basis.

Market Movements and Gap Trading

Next turn to a different question: Should market movements influence your individual stock gap-based trading decisions? For example, assume that the market has been in a strong uptrend and you are considering whether to go long or short with stocks that have gapped up. Do you go long, staying with the stock’s upward movement and the market’s upward movement, or do you perhaps look for a reversal?

Using the same SPDR S&P 500 (SPY) price data we used to calculate market-adjusted returns, we calculate 1-, 3-, 5-, 10-, 30-, and 90-day returns for each trading day from January 1, 1995, to December 31, 2011. To calculate the 3-day return, we first subtracted the closing price from Day –3 price for Day 0 and then divided that result by the closing price from Day –3. Similar calculations were done for the other time intervals. Also, we used data from the last 90 days in 1994 to calculate the 90-day (and other intervals) returns as of January 1, 1995. So for each day in our sample period, we had market returns for six different time periods ending on the day in question.

We then transformed the percentage returns into discrete categories somewhat along the lines of what we did with volume using two different approaches, which was discussed in Chapter 6, “Gaps and Volume.” In the first approach, we categorized the market direction as either “up” or “down.” For example, if the 5-day market return was positive (or zero, which occurs with very low frequency) the market was up for that period. If the return was negative, the market was down. So this variable associated with the 5-day return had only two possible values: up or down. Now consider the results from this approach before moving to the second approach.

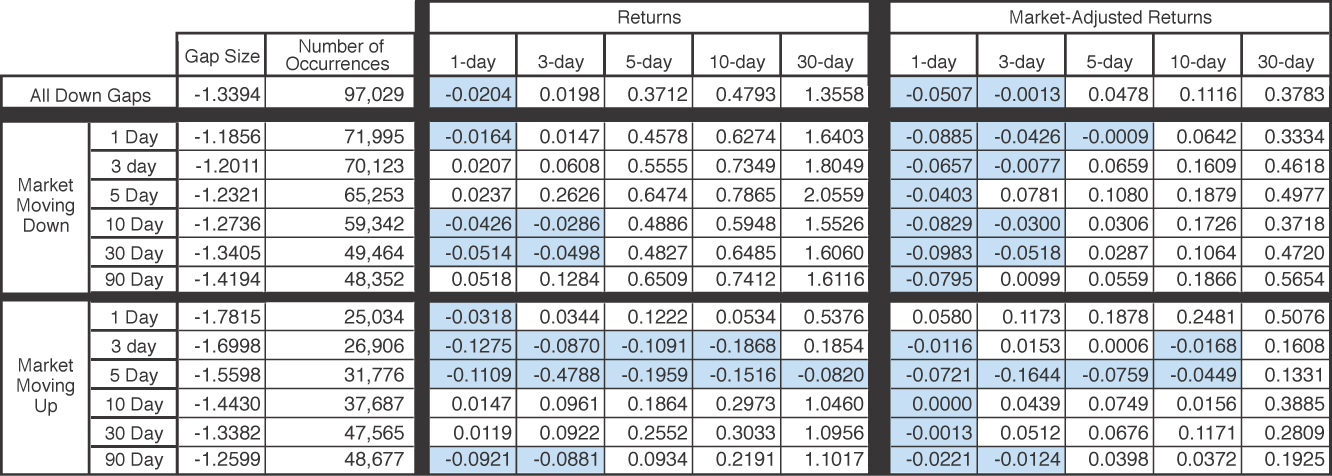

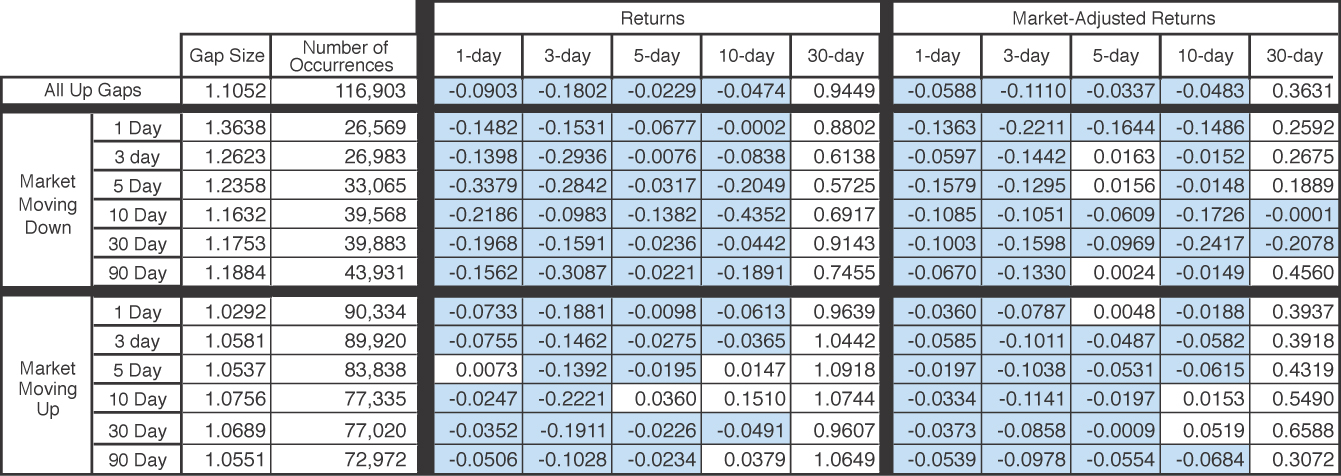

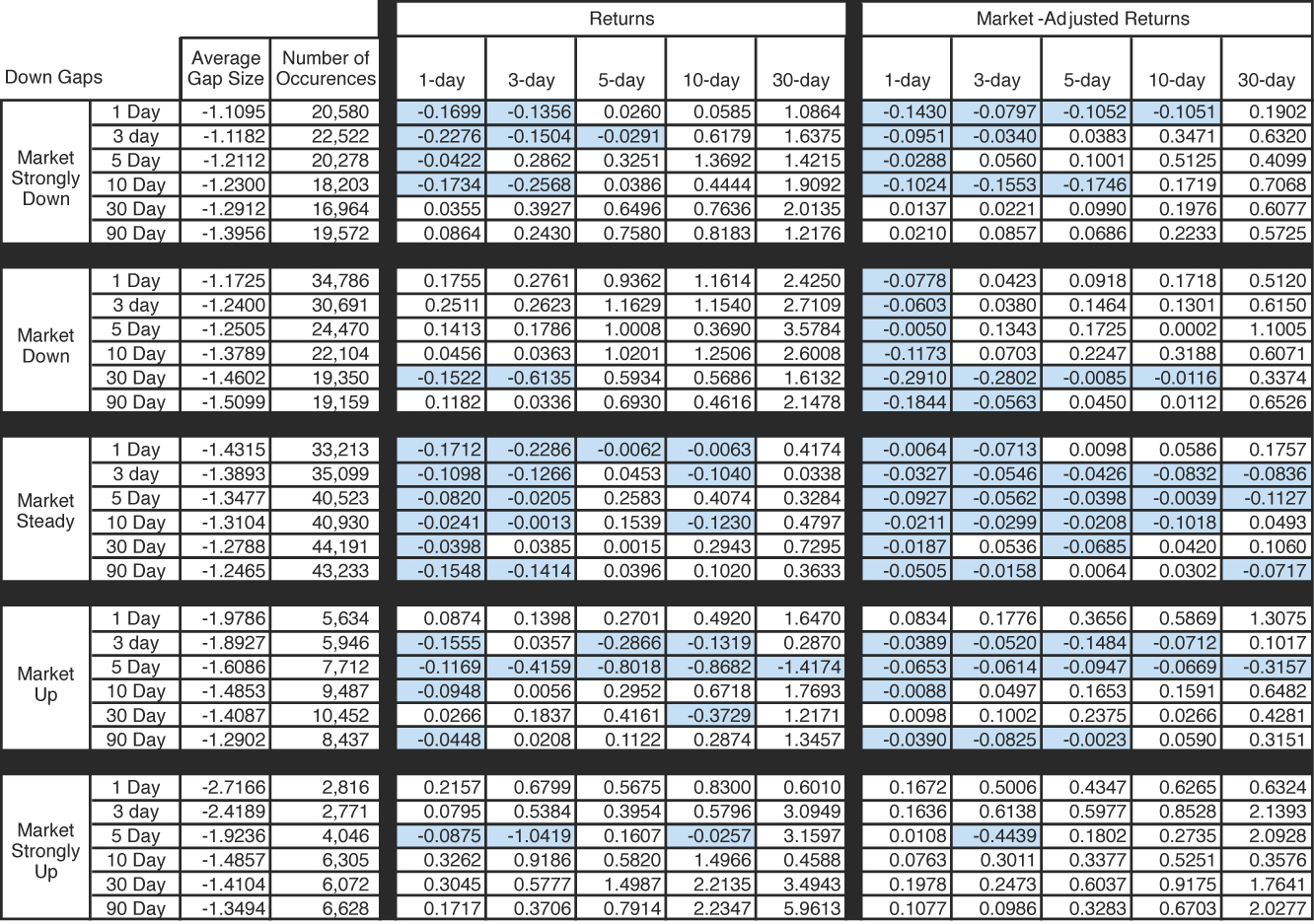

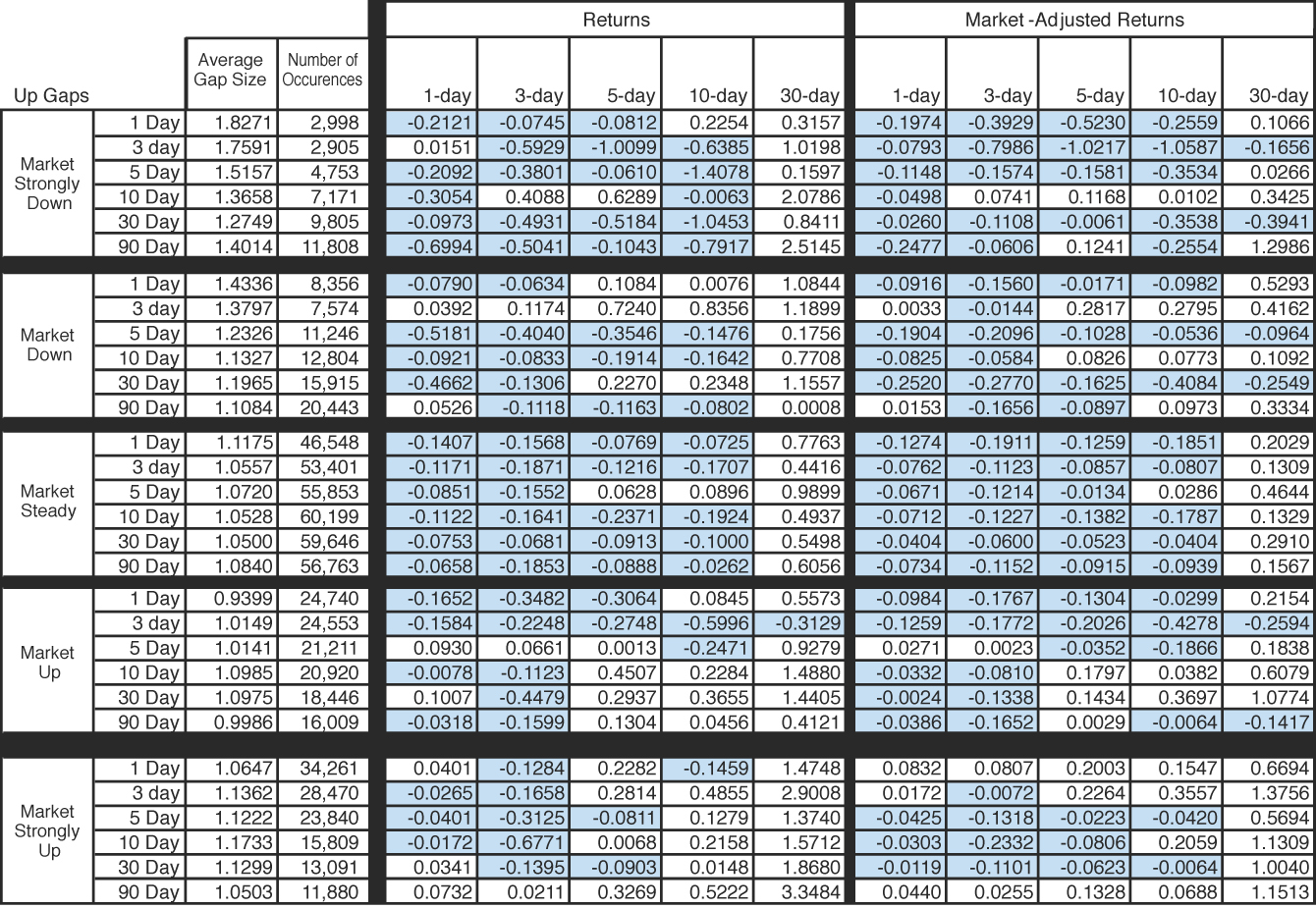

Table 8.5 recaps the results for down gaps, whereas Table 8.6 recaps the results for the up gaps. The upper half of the table deals with the market moving down, whereas the lower half is for when the market moves up. The negative returns are shaded. At the simplest level of analysis, you can ask the same question for both tables: Does the pattern of shading look similar between the upper half of the table and the lower half? If prior market movement has an important impact on returns, you should see different patterns.

Table 8.5. Returns for Down Gaps When the Market Direction Is Down and Up

Table 8.6. Returns for Up Gaps When the Market Direction Is Down and Up

The shading patterns in the upper half of the table look similar to the shading patterns in the lower half for both tables. The shading pattern between the two tables is different; one table is for down gaps and the other is for up gaps. Therefore, gap direction does seem to make a difference. But, within each table separately, the top half appears to be similar to the bottom half. That would point toward the conclusion that prior market movement is irrelevant.

But there is a little more to the story, at least concerning down gaps. Look at the differences in the values between the upper half and lower half of each table. For the up gaps (Table 8.6) you don’t see any particular pattern to the differences. But for the down gaps, the unadjusted returns are higher in 20 out of 25 cells for the market moving down (the upper half) section. Furthermore, the difference is quite substantial in many cases. For example, compare the 30-day returns for the market moving down over the last 3 days’ row to the market moving up over the last 3 days’ row; the numbers are 1.8049 and 0.1854, respectively. That is a difference of 1.6195%. Patterns are nice to have when investing. It would be nice if the market-adjusted returns showed a similar pattern, however they do not.

So what can you conclude from these two tables? For up gaps, prior market movements don’t seem to impact returns (both unadjusted and market-adjusted) in any identifiable manner. The same is true for down gaps, but there is one interesting difference to consider. The returns for long positions are generally higher if the prior market movement is also down. However, there isn’t much difference when the returns are market adjusted.

The market up/market down approach is simple but does not distinguish between low and high values; a return of +0.2% is counted as up, but so is a return of +20%. With the second approach, we put the return into one of five categories: market strongly up, market up, market steady, market down, or market strongly down. The groupings are akin to the volume groupings used in Chapter 6, but the procedure for determining the groupings was quite different. The same procedure was used for the 1-, 3-, 5-, 10-, 30-, and 60-day market returns, but we used the 1-day returns to describe the process. We took all the 1-day market returns for all 17 years in the study and sorted them from lowest to highest. Then we identified the bottom 10%, bottom 25%, top 25%, and top 10% of the returns. If the return was in the bottom 10%, we labeled it as “market strongly down.” If it was in the bottom 25%, we labeled it as “market down.” We designated the top returns similarly. All returns that fell in the middle were labeled as “market steady.”

This approach does have some problems with it. Data is used in later periods to determine a value for something that occurred in an earlier period. An investor in 1995 would have had no way to know whether, for example, the 5-day market return that was just observed would have been a case that could be considered “market strongly down” relative to market returns over the 1995–2011 time period. Therefore, the analysis using this approach merits some caution.

Tables 8.7 and 8.8 show the results from this second approach. Again, focus on whether market movements should have a bearing on how you analyze gaps. Consider the extreme cases first. Focus on the “market strongly down” versus the “market strongly up” sections in Table 8.7. Do you see much of a difference? Yes and no. There are 60 data cells in the unadjusted and market-adjusted entries in the “market strongly up” section of the table. All but 4 of the 60 have positive values. If you look at the “market strongly down” section, there are 42 cells with positive values, about two-thirds of the values. So overall the results are somewhat similar. However, most of the negative values in the “market strongly down” section are in the upper-left corner of the two subsections (“Returns” and “Market-Adjusted Returns”). What does this tell you concerning an investment strategy?

Table 8.7. Returns for Down Gaps in Various Market Conditions

Table 8.8. Returns for Up Gaps in Various Market Conditions

You generally want to go long on a down gap expecting a reversal regardless of the prior market direction. But if the market has been strongly down over just the last 1, 3, 5, or 10 days, then the downward move of the stock may continue for the next 1 to 5 days.

Another difference between the two strong movement scenarios is that the returns are larger in 54 out of the 60 cells for the market strongly up section compared to the market strongly down section. So any reversal that may occur is probably going to be stronger if the market is up strongly.

Comparing the market down to the market up sections, the picture is not as clear. The most striking thing to observe in comparing those sections is that the returns (but not the market-adjusted returns) are lower for the market down section in all but 2 of the 30 cells.

For up gaps the prior market conditions don’t seem to matter too much. Doing the same types of comparisons in Table 8.7 that you did in Table 8.6, you can see there isn’t a marked difference between returns when the prior market movement was up versus down. This was the same conclusion reached when analyzing Table 8.5.

So, concluding this section of the chapter, should market movements influence your individual stock gap-based trading decisions? For up gaps the answer is “no” based on the analysis of Tables 8.5 and 8.6. Down gaps are a bit more complicated. In general, returns are higher for long positions when the prior market movement has been down. Generally, you want to go long on a down gap expecting a reversal regardless of the prior market direction. But if the market has been strongly down over just the last 1, 3, 5, or 10 days, then the downward move of the stock may continue for the next 1 to 5 days.

Summary

This is the longest chapter and there has been much to digest. You began by looking at the 25 days with the highest number (553 or more) of gaps. All 25 have occurred since 2007 and 14 were in 2011. This is another way in which market volatility has been manifested. The underlying causes behind these high gap days was discussed; many were heavily influenced by events outside the United States.

From an investing perspective, you looked at high gap days to see if they gave you any clue about future market direction. For example, if a high number of stocks gapped up on a particular day, is that a signal that the market is headed up or headed down? It did not appear that high gap days dominated by gaps in a particular direction give reliable market timing signals.

You considered two other ideas to make use of the high gap day list. One idea is to look to the dominant group for guidance. For example, if many stocks gapped and 99% of them gapped up, do those stocks that gapped up represent some type of trading opportunity? For days with a high number of down gaps, the best idea seems to be to go short on the down-gapping stocks on the day after the gap, looking for a downward continuation. But, after Day 1 it appears that it would be better to be long, hoping for a reversal. After Day 1 it appeared that being long is a solid idea. The magnitude of the returns is quite high, which is certainly intriguing. The data suggest a similar approach to trading gap up stocks on a day with many up gaps. For Day 1 prices are likely to continue moving up; a continuation approach looks best. After Day 1 a reversal strategy looks better, but the evidence here was not as strong as it was for the down gaps.

A second way to use the high gap day list would be to focus on the small number of stocks moving opposite to the herd. The returns here seem to offer some nice potential. But given the small sample size you dug into the details to see what was causing this group to move in an opposite direction from the majority. What you saw is that some dramatic company-specific event was the cause. Although there appears to be some potential in focusing on this group of stocks, each case needs to be considered separately.

You also examined whether prior market movements should influence gap-based trades. For example, assume that the market has been in a strong uptrend and you are considering whether to go long or short with stocks that have gapped up. Do you go long, staying with the stock’s upward movement and the market’s upward movement, or do you perhaps look for a reversal? For up gaps, you found that prior market movements had little impact. For down gaps it does have some impact. Generally go long on a down gap expecting a reversal regardless of the prior market direction. But, if the market has been strongly down over just the last 1, 3, 5, or 10 days, the downward move of the stock may continue for the next 1 to 5 days.