3

Your Ultimate Test

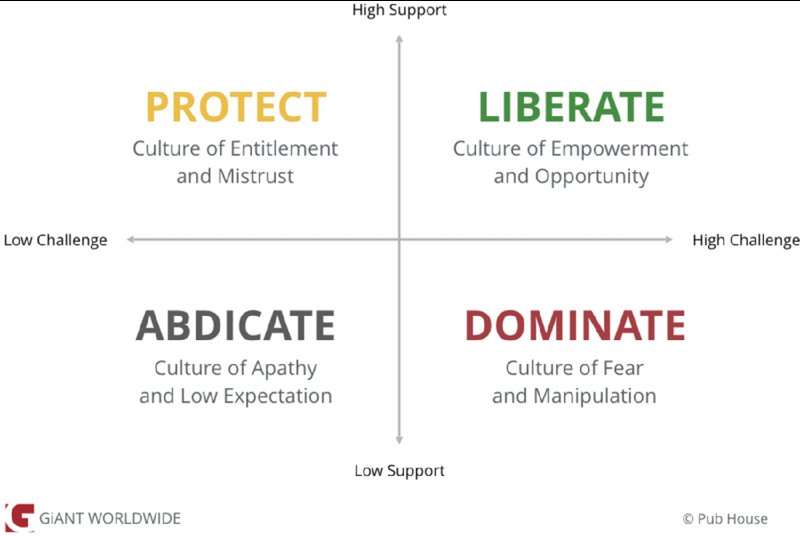

“I couldn’t believe what I was seeing,” said Eddie Backler. “One night on top of the mountain we were sitting in a circle trying to keep warm by a small fire. Just then our Sherpa, Jangbhu, scooped up hot coals in his hands to bring them closer to each of us to keep us warm.” Eddie Backler, CEO of the Charles White Company, a property development company in Edinburgh, Scotland, was on a climb of the Mera Peak in 2009. At 19,000 feet, in the shadow of Mount Everest, Eddie and three other climbers put their faith in the hands of Jangbhu Sherpa who had summited Everest nine times before. Jangbhu quickly captured their respect as they were testing their limits like never before. “We knew he had the wherewithal to get us up the mountain, because the Sherpa was the key to our success,” said Eddie. He goes on to share his experience: “Jangbhu knew what we needed before we did. He knew how to be ahead of us and when to be behind us. It is a real skill. He could read our team and get us to work together without us knowing it. He was assessing us constantly because he had to get us ready for the next levels. And while he could be quite stern, we totally knew he was for us.” Eddie went on to share how Jangbhu Sherpa was so intentional with resourcing the team with the proper food and gear and had a clear plan of attack to climb the mountain. Jangbhu created the trust that all four of them could summit and would do so. Eddie went on to share, “Jangbhu wasn’t a servant we had hired, but rather a fighter for our best. He brought challenge with support. He showed us how to climb the ice cliffs and he pushed us to do things we didn’t think we could do on our own. He would say, ‘you do your bit and I will do mine.’ He would carry our bags when we needed it and would push us to do it ourselves when we needed it. Our Sherpa understood when to push us and when to help us, which was key. And because of that balance and his consistency we trusted him and respected him for who he was.” The Sherpa help people do what they don’t believe they can do. Their secret to helping climbers lies in their ability to provide challenge commensurate to their support. The Sherpa help people do what they don’t believe they can do. Their secret to helping climbers lies in their ability to provide challenge commensurate to their support. Leading people well, consistently, over time, is one of the most difficult things to do in life. Leading people well in difficult circumstances is significantly more difficult. Especially when you know they need to get to a higher level but they cannot yet see it themselves. Leading ourselves well, consistently, over time, can be just as difficult as leading others, especially with the numerous obligations that come with life and work. Family obligations, demanding roles, friendships, busy schedules, and on and on. To become a person worth following is a balancing act, part science, part art. It is the calibration of managing support and challenge consistently with those you lead as well as with yourself. Most leaders default to their natural tendency of oversupport or too much challenge because they tend to live accidentally or out of habit. The Sherpa understands the objective and helps guide people using both support and challenge based on the needs of the moment to get their people to the next level. Leadership is the calibration of support and challenge in order to help those you lead achieve their objectives or tasks that help the team or organization to win. Leadership is the calibration of support and challenge in order to help those you lead achieve their objectives or tasks that help the team or organization to win. Ronald Heifetz, a professor at Harvard University, discusses the realities of overly challenging leadership in his work on adaptive leadership: “It’s often thought that leaders are dominant within an organization and want to use their strong personalities to impose their will. This hierarchical top-down leadership style hasn’t worked for a long time. It hinders the flow of information in companies, undermining cooperation and unity between teams and departments.”1 A Sherpa understands that to maximize influence, you must practice both support and challenge and then learn how to calibrate these with each different person on your team. The same is true with any person or leader. Learning to manage your own personality tendencies and adapt to other people’s patterns is a key to leadership success. Support means to provide the appropriate help others need to do their jobs well: to equip people, serve them, and provide the resources needed for those you lead. Support looks different for different people, but at its purest form it means to equip and resource them for the journey ahead. Challenge, on the other hand, means to motivate people by holding them accountable to what they could do if they had the resources. Challenge is the push needed to get people to move to be the best they can be, either as a team or as an individual. For instance, challenge can be direct with words or indirect with action, but the overall purpose of challenge is to help get people to levels that they never imagined they could get to. How about you? Which do you find more natural, support or challenge, and which one have you had to learn? Which one would those you lead (whether at work or at home) say that you tend to do more? The 100X-leader journey starts at base camp, where you must understand what your tendencies of support and challenge are by being honest with yourself. This is the first step to getting to 100% health in the way you lead. If you tend to provide high challenge but little support, then own it. Or if you naturally give high support with low challenge, then own that. This is the stage of conscious incompetence (realizing exactly where you are coming up short) and the key to becoming someone people want to follow, rather than have to follow. To become a person worth following it is vital that you first establish support with those you lead before you challenge them. Starting with support allows for trust to be established relationally so that challenge can be more easily accepted. John was a vocal leader who expected a lot from his people, and everyone knew it. As general manager, he shared his challenge openly and often. “You know what needs to happen,” he would say. “We are down 4% and the big boss won’t put up with it. Let’s get going!” He would continue to cajole people to execute and “make it happen,” on a daily basis. He was actually quite good at motivating people, and most of the employees did what he asked so they wouldn’t get on his “bad side.” However, over time John’s expectations became unrealistic while the fear of disappointing him or the “big boss” lessened. Although John could overly challenge, his support was earned simply through driving results. In time, the people began to wonder if John truly cared for them or their success. This is where the grumbling and complaining began—to anyone but John. His team would ask for help on some equipment innovations of this manufacturing company to no avail. “You guys always want something, don’t you?” John would say. “No more excuses, let’s go. Make it happen.” Although they asked for a specific type of machinery to do what he needed them to do, John didn’t listen. Over time his team would avoid going to John directly to ask him for anything, because they were always told, “that is what we pay you for—figure it out!” The harsh challenges to his team became even less effective, and his people did just enough to keep their jobs, but little more. The “big boss” grew more and more frustrated, but because John’s team didn’t receive the resources they needed, they struggled to hit their quotas. John became more and more agitated. He eventually went “nuclear” with the ultimate threat of layoffs. His challenge became more and more blatant and threatening as he started to say things like, “Maybe I should just clean house, the whole lot—just start over.” He made some layoffs: “That will scare ‘em,” thought John. However, it only made things worse. The employees and his team, desperate to save their jobs, started to protect each other against John and the “big boss.” Eventually, the employees had enough and began to leave for lateral jobs where they had a better boss. This exodus of employees, coupled with the continued layoffs, turned the culture of the company toxic as the employees told all those looking for employment there to stay away. The “big boss” started to consider moving the manufacturing plant because, according to John, the workers in this city were “scarce, lazy, and spoiled.” Eventually, the company was sold to another private equity group who had more specialism in handling companies that need to be turned around in this sector. In came the new management team with a similar message: “We know how to turn companies like this around. If you want to keep your jobs then you need to keep your head down, work hard, and do what your leaders say.” One midmanager from the manufacturing floor was sent in to ask management for the new equipment to enable them to work smarter. He was quickly told to return to the floor, with the usual response, “That is why we pay you; figure it out.” Unfortunately, there was not a happy ending to this story. The long-term overchallenge and lack of support created a culture rift that affected their market share and their reputation. If you want to create success with your people or your organization then you must calibrate support before challenge. If you want to create success with your people or your organization then you must calibrate support before challenge. The art of leadership, then, is the appropriate calibration of support and challenge at a specific moment, in a specific context for a specific person. When you are trying to establish healthy communication and relational trust it always requires the investment of time. From this perspective support is not soft, it’s a strategic decision a leader makes because they understand the long-term return on their investment. Years ago, we started to unpack the 100X concepts of support and challenge that was written about in my (Jeremie’s) first book, Making Your Leadership Come Alive (Leadership is Dead). We were playing with the liberating/dominating constructs of the book when Steve added two other components, protecting and abdicating, around the four-box matrix he had seen from some work from his friends at DDA Consulting. We then devised a more helpful version of the Support-Challenge Matrix to create a scalable visual tool. The matrix is simple, but powerful (see Figure 3.1). There are two axes. The y (vertical) axis is support, with high support at the top and low support at the bottom. The x (horizontal) axis is the challenge axis, with low challenge on the left and high challenge on the right. We then created a standard of leadership behavior and the culture that leadership behavior creates in each quadrant. Figure 3.1 The Support-Challenge Matrix Source: © Support-Challenge Matrix, Pub House/GiANT Worldwide. The best leaders in the world operate in the top right quadrant—they liberate. These leaders have learned how to function by liberating more often each day in every part of their lives and thus have earned the distinction of becoming people worth following. It is important for you to understand that most of us will visit each quadrant on most days. None of us are perfect. However, the more time we spend in the top right quadrant, the more effective we become. But it doesn’t come naturally! Here is how Nick Green, a British executive of a major corporation, reacted: I have been somewhat aware of the fact that I dominate in some situations and abdicate in others, but I’ve not had the tools to understand what’s going on. I was a protector, abdicator, dominator and sometimes liberator—but always subconsciously and never intentionally. For me the Support-Challenge Matrix was like having cataracts in my eyes fixed. Finally, I could see what was going on and I understood what I was doing and the impact I was having on other people. Initially I applied this new found learning to myself at work, which helped enormously; I realized I could challenge people without it being confrontational! Then once I’d cracked that and started to do more things intentionally each day, I turned my thoughts to all the other versions of me: the husband, dad, mate in the pub and bloke on the committee. Seeing my life through the lens of the Support-Challenge Matrix has helped me—and those around me—hugely. I still have to think about what I’m doing—but at least I’m thinking now! That is our hope for you—we hope you begin to intentionally think about who you are and how you are leading others and in doing so that you might experiencing the fulfillment of being the leader that you have always wanted to be. Let’s look at each of the four quadrants. Very few people choose to dominate other people. It is usually not a conscious decision, and yet most of us have times when we do. Dominating others means that our tendency is to bring challenge, but little support. It is the act of requiring much, but resourcing little, which is not fair to those we lead or love. This often occurs out of habit from stress rather than a deliberate decision. The dominating quadrant is red, as those who dominate tend to coerce and brow beat people with fear and manipulation when they feel like they aren’t winning or if control is slipping out of their grasp. They usually assume that others like them but may be out of touch with the hard reality of what it is like on the other side of themselves as leaders. Those who have a tendency to dominate are not evil people, of course, but simply focused on getting results by using methods of challenge that bring fear, not empowerment. They don’t tend to realize that they are significantly limiting their influence to those they lead because of these actions. We often hear, “But don’t you think that there are times when you need to dominate inside the organization?” Our quick reply is, “You mean, do we think there are times when you need to cause fear and manipulation? No, not at all!” There are times when we need to bring more challenge, for sure, but not to abuse power with overcontrol and cause fear or anxiety. High challenge is only effective if it is calibrated with high support. It must be intentional and thought through. If you react in the moment out of frustration you will normally get it wrong. Oftentimes, domination comes as a habit, learned from an overbearing parent or coach or boss who yelled in order to get their way. This is simply repeating what you have seen others do around you. Our goal is to get you to the place where you can see what it is like to be on the other side of you and begin to adjust. Do those who dominate get things done? Absolutely, but so do those who liberate, and the experience of people on the other side of each is dramatically different. Dominating leads to compliance, whereas liberating produces engagement. That difference is what makes leaders great. It is simply not possible to thrive in your work when you are placed in a red culture of fear and manipulation. People eventually burn out and have to be replaced. This is no way to build effective leaders. Dominating leads to compliance, whereas liberating produces engagement. Listen to Mike Oechsner, VP of TEAMTRI describe his journey to liberation: I realize now that, especially in times of stress, I was a very dominating leader to my team, which, in times of high pressure, already had more than enough challenge facing them. Me bringing more challenge—really, bringing anything other than unqualified support at those times—just magnified the stress, and the challenge I was bringing was unnecessary and unhelpful. I wasn’t taking time to reflect on my lack of influence because I was so busy doing the work and expected everyone else to do what needed to happen when it needed to happen without thinking about getting them engaged instead of having them comply. I look back through texts and e-mails and can see my challenge in my tone and my lack of tact. I am changing and I can see it, but it takes a conscious effort to say the least. The connection I have with my team gets better, measurably, every day, and in every interaction I’m able to use the Support-Challenge Matrix as a lens. I find myself having fewer conversations about what I could have done better and having more conversations in the moment asking how I can bring support for great results in communicating, leading, running our events, etc. When I would dominate, I definitely could get results, but they were at a cost in relationship, influence and rapport. People just didn’t want to follow me as much as they had to follow me. That is changing on this journey to liberation and while I am still getting results, the cost is much lower and the rewards are almost immeasurable. Those who protect give more support and rarely take time to share challenge or even reasonable expectations. Although this can feel comfortable and easy, ultimately overprotection creates a culture of entitlement and mistrust, as those who protect can flip from Dr. Jekyll to Mr. Hyde in their inconsistent leadership style. At their core, a person who protects sees even healthy challenge as conflict, and does anything to avoid it, wanting everything to just run smoothly. When there is a need for correction or challenge (or even just setting reasonable expectations), those who protect will tend to hint over and over until they get what they want. “Hey Amy, how are you? Are we all set with the big event next week?” (hint, hint). When they are not satisfied with the results or answer, they come back days later with another hint—“So, Amy, after talking with Brenda I wanted to check back in with you on the event. Are we all set? Is there anything we are missing?” Hinting can be confusing for everyone. One week later and still not happy, the protecting leader can suddenly become quite stern and switch to challenge-only micromanagement. “Amy, this is the third time we have talked about this. I am going to ask Brenda to jump in and help you since she kind of knows what we are working on and you guys will get along great.” All Amy heard was two niceties about the event and then after the third conversation she is now being subverted and replaced by Brenda. Without having a clue why this happened, Amy begins to ask around if anyone else saw this happening. Protecting leaders create sideways energy because they are not clear enough in the beginning with their expectations. The color of protecting is yellow because these people create caution in their cultures due to the inconsistencies that tend to occur in their leadership style. Here is an example of a CEO in Atlanta, Georgia, reaching the reality that she was protecting her employees and the effect it had: Before I’d been introduced to GiANT, I thought I was a personality profile/HR expert and I had nothing to learn. Well, boy, was I wrong! I own a recruiting firm where my employees are part-time moms. With my personality, my natural tendency is to dominate. But I realized during my time with GiANT that I actually protect my staff. I have been overcompensating because I am sympathetic to the life of a stay at home mom/employee. I know that it is hard to do both—so instead of holding to high challenge as would be natural for my personality type—I actually went the other way and gave high support (which I have learned from my 30 years of HR training) and no challenge. In fact, I would say, “Oh I understand that you didn’t hit your numbers,” “Oh, no problem you can’t be at our team meeting,” etc. But ultimately, the reason I was unhappy with the company was because I felt like I was the only one doing anything. This January I did a restart of our culture and let all of my staff know that it was a new day, that although I understood their time pressures, we are a business and I’m not responsible for their personal issues. I reminded them that they have a job description and will be held accountable to that. So, I am working toward Liberating where my high support is also met with some high challenge, and I am finding that people are responding very favorably. —Cindi Filer, CEO Innovative Outsourcing Whether you lead a business, a nonprofit, or a family, it is important to realize that the best leaders in the world share expectations well, while continuing to give the support that others need. To abdicate means to give up, avoid, relinquish, forgo, abandon, turn one’s back on. Abdication usually occurs when people don’t fully perform their duties or the responsibilities needed of their role. When a leader abdicates, it can be for many reasons. The leader may be worn out by the overwhelming tasks of the job or have switched off due to office politics or through sheer boredom with lack of challenge. Sometimes, abdication can occur from self-preservation or the fear of being rejected. Whatever the reasons, abdication is a sad place to live or lead. The color for abdication is gray because it creates lifeless cultures with low expectations for all those they lead. Some people abdicate because they don’t believe they have the positional power to shape the culture. This professor shares her reality here: You don’t need to be the boss to bring meaningful leadership to an organization. I am currently an Associate Professor without a formal leadership position at a public University. Spending 10+ years in academia led me to believe that culture is ingrained and resistant to change, and that it would take more than an inspiring boss to shift ways of thinking. After working with my GiANT Sherpa, I now realize that I was primarily abdicating. Since I was not in a formal leadership position, I thought that it was inappropriate to bring challenge to others. As a team member, I accepted that things happened that were not in my control, and as a result, that passive acceptance made me a likeable and good employee. I did not realize that bringing challenge does not have to be adversarial and can be liberating. I took the initiative to create an informal support group for junior faculty called “Connected Colleagues.” We meet monthly via videoconference and by utilizing the 100X tools, I have informally coached and mentored my colleagues through difficult discussions, tenure/promotion struggles and helped them recruit new faculty members. My peers now think of me as an influential leader of the faculty and will often seek my opinion before having “tough conversations” with administration or students. This role has given me a tremendous amount of job satisfaction—my colleagues see that my own efficacy has improved as I’ve learned to lead myself, and they too can benefit from what I’ve discovered. —Mary Onysko, Clinical Associate Professor of Pharmacy Practice, University of Wyoming To liberate is to empower those you lead. We believe that 100X leaders are the best leaders in the world because they have learned how to liberate those they lead in every circle of influence [self, family, team, organization, and community]. The problem is that there are just too few of them in the world. Hopefully, you have experienced someone who has liberated you in your life—maybe a sports coach who was so encouraging that they pushed you to your personal best, or a teacher who gave much of his or her time to get the most out of you. It could have been a parent, a grandparent, or your boss. One of our friends, Kevin Weaver, wrote a book called Re-Orient that shaped our view of the liberating leader concept when he shared this definition—“Love means to fight for the highest possible good in the lives of those you lead . . . until it is a current reality.” We have taken that definition as the action of those who liberate; to liberate means to fight for the highest possible good of those you lead. To liberate means to fight for the highest possible good of those you lead. Liberating leaders turn things green; they build healthy teams and cultures, and they produce a level of relational trust that takes performance to higher levels. Here is a good example of liberation in action: I realize now that I had a tendency to dominate inside my organization. Now I have learned how to liberate and I have seen tangible breakthroughs that I would love to share. I realized that I am responsible for my own leadership journey. As a 100X leader, I am now committed to making sure that I am one of the healthiest people in the room, and constantly look for opportunities to offer support to others in the organization. I also understand the importance of asking for support when needed. I have also become more receptive to external challenge and have learned to approach this with a “nothing is impossible” mindset. The benefits of liberating are numerous. I have developed better relationships with colleagues, there is a greater commitment to accomplishing college initiatives, communication is more transparent, and trust is more evident between us because of the calibration of support and challenge and the consistency that is happening. As someone who now liberates, I appreciate the contributions of others and I know that I am empowered to create opportunities that will positively impact the organization’s pursuit towards excellence. Simply stated, I am a much better leader! —Damita Kaloostian, Dean, South Mountain Community College, Phoenix, Arizona Several years ago, we were helping a manager of a company work through their team culture and specifically his style of leadership. As the Support-Challenge Matrix was drawn on a white board in front of his team, we asked this leader if it was okay to take the support challenge test by getting the team to plot his reality on the matrix. He agreed, but I could tell that his team was nervous about plotting their leader in front of him. I asked the leader to step out of the room and then, one by one, his people came to plot him on the board. The results were not as the leader expected—the average plot put him square in the dominating category. As he returned, he tried to make a joke of it, saying, “Come on guys, really? You threw me under the bus in front of him?” When I asked this leader where he would plot himself, he said, “right in the middle” of the liberate quadrant. The journey from dominating to liberating would be his 100X journey. During the break he confided that he didn’t understand it but he wanted to improve, which is the best response when people realize they are consciously incompetent. All leaders with a default tendency toward dominating want to win and want to become more competent. They may just need to be helped to see this reality. His question was, “How do I bring more support when I thought I already was bringing support?” The answer was, “Ask your team.” We then took the next 30 minutes to ask his team what support would look like for them. Here are their surprising answers: These are not massive issues, or even difficult things to do, but they all add up to big things long term. Most leaders arrive before their people and have already begun thinking about their days. Oftentimes the leader will begin peppering people about situations or barking orders before their teammates are warmed up. Just remember, little things add up to become big things in the long term, and ultimately your reputation is based on how you make people feel. A few years later we had another session with this leader and his team. When we did the same exercise, they let us know that he had made it across the liberate line, which quickly led to a smile and a “high-five.” This leader decided to go on the extremely difficult journey of becoming a liberating leader. He has been climbing the mountain, learning tools along the way to become a leader worth following, not just someone that people have to work for. He has been transitioning from a dominating tendency to liberating, both at work and at home. People are smart. They can smell the leader’s intent from a mile away. They tend to know if the leader is for them, for themselves, or against their teams or people. Are you for people or for yourself? Most people are not necessarily bad people, they are just living accidental lives and not realizing that they are living incongruently with who they truly want to be. It can be different! Change can happen if you want to become someone worth following. The questions you need to ask yourself are: A Sherpa liberates others only after they have liberated themselves. They then focus on helping others get to the higher levels that they have experienced. When they do, their influence and reputation grows with them.

More Support or More Challenge?

Start with Support

The Support-Challenge Matrix

Dominating

Protecting

Abdicating

Liberating

Support Challenge Test

Your Intent

Note