8.

THE TRAP OF SHAREHOLDER VALUE

On the face of it, shareholder value is the dumbest idea in the world.

—JACK WELCH1

“Imagine an NFL coach,” writes management guru Roger Martin in Fixing the Game, “holding a press conference on Wednesday to announce that he predicts a win by 9 points on Sunday, and that bettors should recognize that the current spread of 6 points is too low. Or picture the team’s quarterback standing up in the postgame press conference and apologizing for having only won by 3 points when the final betting spread was 9 points in his team’s favor. While it’s laughable to imagine coaches or quarterbacks doing so, CEOs are expected to do both of these things.”2

Imagine also, extrapolating the analogy, that the coach and his top assistants are compensated not according to whether they win games, but by whether they cover the point spread. If they beat the point spread, they receive massive bonuses. But if they miss covering the point spread a couple of times, the salary cap of the team could be cut, the coach fired, and key players released, regardless of whether the team won or lost its games.

Suppose also that, in order to manage the expectations implicit in the point spread, the coach had to spend most of his time talking with analysts and sportswriters about the prospects of coming games and managing expectations about the point spread, instead of actually coaching the team. It would hardly be a surprise that the most esteemed coach would be a coach who, over multiple years, met or beat the point spread in 46 of 48 games—a 96 percent hit rate. Looking at these 48 games, one would be tempted to conclude: “Surely those scores are being fixed?”

Moreover, think what it would be like if the whole league was rife with scandals of coaches deliberately losing games (“tanking”), players sacrificing points in order not to exceed the point spread (“point shaving”), paying the referees to improve the score (“fixing the game”), or outright wagering on the results of games (“gambling”).

If this were the situation in the NFL, everyone would realize that the “real game” of football had become utterly corrupted into some form of gambling and manipulation. Everyone would be calling on the NFL Commissioner to intervene and ban the coaches and players from being involved in gambling or fixing the games, and get back to playing the game of football.

Which is precisely what the NFL Commissioner did in 1962 when some players were found to be betting small sums of money on the outcome of games. In that season, Paul Hornung, the Green Bay Packers halfback and the league’s most valuable player, and Alex Karras, a star defensive tackle for the Detroit Lions, were found betting on NFL games, including games in which they played. Pete Rozelle, just a few years into his thirty-year tenure as league commissioner, took immediate action. Hornung and Karras were suspended for a season. As a result, the real game of football in the NFL has remained largely separate from gambling or fixing the score. The coaches and players spend their time and effort trying to win games, not gaming the games.3

![]()

In today’s paradoxical world of business, where many public corporations focus on maximizing shareholder value as reflected in the share price, the situation is the reverse. CEOs and their top managers have massive incentives to focus their attention on fixing the share price in the stock market, even at the cost of hurting the firm. Thus, a survey of chief financial officers has shown that “78 percent would ‘give up economic value’ and 55 percent would cancel a project with a positive net present value—that is, willingly harm their companies—to meet Wall Street’s targets and fulfill its desire for ‘smooth’ earnings.”4

The real world of business is the world in which factories are built, software is developed, and real products and services are designed, produced, and sold that make a real difference in customers’ lives. Real dollars of earned profit show up on the bottom line. In a healthy economy, firms focus on creating real value for customers. The economy steadily grows.

The real world of business differs from the stock market, where shares in companies are traded between different kinds of investors. In the stock market, investors assess the resources and activities of a company today. Based on that assessment, investors form expectations as to how the company is likely to perform in future, as well as how much value the firm will return to its shareholders. The consensus view of many elements—the views of actual and potential investors, assessments of the current worth of the company, and the firm’s plans for returning value to shareholders—combine to determine the stock price of the company. Some investors are in it for the long haul; others are traders out to make short-term profits from the volatility of the market.

In the current stock market, the best managers are seen as those who meet expectations. “During the heart of the Jack Welch era,” writes Martin, “GE met or beat analysts’ forecasts in [46 of 48] quarters between December 1989 and September 2001—a 96 percent hit rate. Even more impressively, in 41 of those 46 quarters, GE hit the analyst forecast to the exact penny—89 percent perfection. And in the remaining seven imperfect quarters, the tolerance was startlingly narrow: four times, GE beat the projection by 2 cents, once it beat it by 1 cent, once it missed by 1 cent, and once by 2 cents. Looking at these twelve years of unnatural precision . . . What is the chance that could happen if earnings were not being managed?” Martin replies: “Infinitesimal.”5

In such a world, it takes a dedicated chief executive to do the hard, long-term work of undertaking innovation in an increasingly competitive marketplace populated with unpredictable customers. It’s much simpler, easier, personally safer, and more lucrative to boost the stock price by cutting costs to enhance the apparent short-term performance in the firm’s quarterly earnings, or to use financial engineering to extract value for shareholders.

In fact, a CEO of a public company has little choice but to pay careful attention to the stock market, because if the firm’s share price falls markedly, accounting rules require that it be classified as a goodwill impairment.6 Auditors may then require the company to record a loss of capital. Even more worrying, in such settings, activist hedge funds may launch campaigns to oust the management and put in place executives who are more “shareholder friendly.” Thus, most executives perceive themselves to be under continuous pressure to maintain a high stock price.

By March 2016, The Economist could proudly declare that shareholder value thinking is now “the biggest idea in business.”7 That may be so, but it is also “the error at the heart of corporate leadership,” according to two distinguished Harvard Business School professors—Joseph L. Bower and Lynn S. Paine. Maximizing shareholder value, they write, is “flawed in its assumptions, confused as a matter of law, and damaging in practice.”8

Even Jack Welch, who was the heroic exemplar of shareholder value during his twenty-year tenure as CEO of GE, has become its harshest critic. “On the face of it,” he told the Financial Times in 2009, “shareholder value is the dumbest idea in the world. Shareholder value is a result, not a strategy . . . your main constituencies are your employees, your customers, and your products. Managers and investors should not set share price increases as their overarching goal. . . . Short-term profits should be allied with an increase in the long-term value of a company.”9

It often comes as a surprise to Agile practitioners that an obsession with the short-term share price should be so widespread in public corporations today. Where did this notion come from? It is often presented by its proponents as an immutable truth of the universe. Yet its origins are surprisingly recent.

![]()

In the middle of the twentieth century, the conventional wisdom on running a corporation was something called “managerial capitalism.” As expounded in the 1932 management classic The Modern Corporation and Private Property by Adolf A. Berle and Gardiner C. Means, the idea was that public firms should have professional managers who would balance the claims of different stakeholders, taking into account public policy.

This led to problems. Organizations became confused. Balancing claims by professional managers sounded good in theory. In practice, it often led to inconsistent and ill-defined priorities. Sometimes even the firms’ managers couldn’t understand their own processes. Decision making became unpredictable and capricious. Closure was reached only when shifting combinations of problems, solutions, and decision makers happened to coincide. Poorly understood problems wandered in and out of the system. Some theorists called it “garbage can management.”10

That way of managing a corporation was unable to cope with the forces of globalization, deregulation, and new technology that were emerging. The careful weighing of competing stakeholder claims by professional managers was a poor fit with the faster pace of change, increased competition, and the growing power of the customer—a veritable apocalypse of change.11

Greater clarity in terms of purpose was needed. As discussed in earlier chapters, some firms followed Peter Drucker’s lead and embraced the primacy of the customer. They recognized that in the emerging marketplace, firms would have to deliver more value to customers. Firms would have to become radically more innovative and nimble, just to survive. In due course, this led to the advent of management practices such as lean, design thinking, quality, and eventually Agile management.

But other public corporations headed in the opposite direction and gave primary attention to shareholders. Their initial champion was the Chicago economist Milton Friedman. Already, in his 1962 book, Capitalism and Freedom, Friedman, who was to win the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1976, had rejected Peter Drucker’s view that the only valid purpose of a firm was to create a customer. Instead, he declared that “there is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.”12

On September 13, 1970, Friedman set out to popularize his thinking. He published an article in The New York Times castigating any business managers who were not totally focused on making profits. In his view, such managers were “spending someone else’s money for a general social interest.”13

Friedman recognized that executives were not responding effectively to the apocalypse of change under way in the marketplace. His 1970 article sliced through these problems like a knife. Managers should focus on one thing and one thing only: making money for shareholders. Everything else was irrelevant. The shareholders owned the company. Executives worked for the shareholders. The corporation was “a legal fiction.” (See Box 8-1.)

The tone of Friedman’s article was ferocious. Any business executives who pursued a goal other than making money for the company were “unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of a free society these past decades.” They were guilty of “analytical looseness and lack of rigor.” They had even turned themselves into “unelected government officials,” who were illegally “imposing taxes” on employees, customers, and the corporation.14

For executives who were struggling to find their way through the ongoing apocalypse of change, Friedman’s proposal offered irresistible clarity: Managers need only focus on making profits and the rest would take care of itself.

The success of Friedman’s article was not because the arguments were intellectually compelling—they weren’t. It’s rather that executives wanted to believe. They were desperate to find a profitable path forward. Friedman’s article was a godsend. They no longer had to worry about balancing the claims of employees, customers, the firm, and society. They could concentrate on making money for the shareholders. Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” would make everything else come out right. (See Box 8-3.)

![]()

In 1976, two new champions emerged. In one of the most-cited but least-read business articles of all time, finance professors William Meckling and Michael Jensen offered a quantitative economic rationale for maximizing shareholder value, along with generous stock-based compensation to executives who followed the theory. The article explained how the personal interests of executives could be aligned with those of the corporation and its shareholders. Compensation in stock would turn the executives into part-owners of the firm and so protect the other part-owners—the shareholders—against the managers wasting cash on corporate jets, lavish new headquarters, and other monuments to executive extravagance. Now managers would act like owners. They would focus on doing “the right thing”—making money for the owners—and be well compensated for doing so.15

The message was seductive. It created a mandate for finance—namely, those who saw the enterprise largely through the lens of the numbers: sales figures, costs, budgets, and profits—to take charge of the corporate boardroom. Now only one thing mattered: Did it make money for the firm’s owners? Since the executives themselves now were also part-owners, the approach had a happy side effect: They could become rich in the process.

In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher gave the idea political cover: Business should get back to basics. Government was the problem, not the solution. The business of business was the business of making money, pure and simple. Corporate raiders like Carl Icahn were happy to become the enforcers.

An important accelerator was a 1990 article in Harvard Business Review by finance professors Michael C. Jensen and Kevin J. Murphy. The article, “CEO Incentives—It’s Not How Much You Pay, But How,” suggested that many CEOs were still being paid like bureaucrats and that this caused them to act like bureaucrats. Instead, they should be paid with significant amounts of stock so that their interests would be aligned with stockholders. “Is it any wonder,” Jensen and Murphy wrote, “that so many CEOs act like bureaucrats rather than the value-maximizing entrepreneurs companies need to enhance their standing in world markets?”16

And indeed, CEOs became very entrepreneurial—but often in their own cause, not necessarily the organization’s cause. The article was very well received on Wall Street. The use of the phrase “maximize shareholder value” exploded. Compensation practices changed. Stock-based compensation became the norm for the C-suite. Shareholder value became the gospel of American capitalism.

Over time, corporate raiders cleverly rechristened themselves with the gentler term “activist hedge funds,” as if to imply that they were performing a noble civic duty, not merely grabbing cash for themselves. But the name change didn’t change the game plan.

Activist hedge funds set out to extract value even more systematically, by purchasing equity stakes in corporations and enlisting other shareholders—even public-sector pension funds—in carefully orchestrated campaigns to put pressure on the management to “unlock value” and so get their hands on the firms’ assets.

The theory of maximizing shareholder value can be summarized thus:

A firm should focus on and dedicate its management and all employees to making as much money as it can for its shareholders. Such a focus, which utilizes executive stock-based compensation, will not only result in the greatest benefit to shareholders. It will also, through Adam Smith’s “invisible hand,” result in the optimal allocation of societal resources. The measure at any point in time of how well the firm is prosecuting the goal is the current stock price, which is the truest reflection of the value of the firm. The current stock price thus offers a metric by which the daily activities of a firm can be evaluated and the long-term value of the corporation promoted.

![]()

Like most bad ideas that achieve wide acceptance, shareholder value theory contains several grains of truth. One is that generating long-term value for shareholders is a good thing. If firms serve customers well and organize employees in ways that allow them to express their talents in service of customers, the company and shareholders will prosper and society will be better off.

A second is that a clear focus on outcomes is important to protect shareholders against managers wasting cash on various forms of executive extravagance—the so-called agency problem. Another partial truth is that having a single clear goal against which progress can be easily measured could be a distinct advantage in disentangling the conflicting priorities of the “garbage can management” that was prevalent in the mid-twentieth century.

Yet there was a risk. The pursuit of a single clear goal, if it was the wrong goal, could become a practical, financial, economic, social, and moral disaster.

Thus, while the idea of having business focus on solely making money for shareholders had a kind of street-corner logic to it, a sole focus on shareholders also had risks that its academic champions failed to anticipate. (See Box 8-4.) Over the ensuing decades, shareholder value theory not only failed on its own narrow terms of making money for shareholders, but it began destroying the productive capacity and dynamism of the entire economy.

Today, symptoms of the ensuing economic malfunction are everywhere apparent. A large pharmaceutical company systematically keeps buying other companies, cancels their drug research, and uses the resources to buy still more pharmaceutical companies—until the pyramid scheme abruptly collapses.17 A major news organization turns a blind eye to sexual harassment to protect short-term profits.18 A global auto manufacturer uses a software device to enable its diesel-driven cars to circumvent environmental regulations.19 Firms rip off pension funds, even stuffing them with cheese, Scotch whiskey, and golf courses.20

Financial resources are being diverted from needed investments in innovation.21 A brilliant study by economists from the Stern School of Business and Harvard Business School, entitled “Corporate Investment and Stock Market Listing: A Puzzle?,” compares the investment patterns of public companies and privately held firms. They found that, keeping company size and industry constant, private U.S. companies invest nearly twice as much as those listed on the stock market: 7% of total assets versus just 4%. Contrary to what the academic economists had predicted in putting forward the theory of shareholder value, compensating executives with stock had made them less entrepreneurial for the firm, not more. As a result, the economic recovery from the Great Recession of 2008 was undermined and the ability of firms to innovate was restricted.22

The impact on the workforce was also significant. Manufacturing jobs were steadily sent to other countries with cheaper labor costs. In the process, public corporations, while presenting themselves as job creators, became net job destroyers. “In fact, between 1988 and 2011,” write Jason Wiens and Chris Jackson of the Kauffman Foundation, “companies more than five years old destroyed more jobs than they created in all but eight of those years.”23 (See Figure 8-1.)

Shareholder value thinking has even put in question America’s ability to compete in the international marketplace. “The basic narrative,” says a comprehensive report from Harvard Business School, “begins in the late 1970s and the 1980s . . . firms invested less in shared resources such as pools of skilled labor, supplier networks, an educated populace, and the physical and technical infrastructure on which U.S. competitiveness ultimately depends.”24 The overall result: “Virtually all the net new jobs created over the last decade were in local businesses—government, health care, retailing—not exposed to international competition. That was a sign that the U.S. businesses were losing the ability to compete internationally.” (See Chapter 10 and especially Box 10-2.)

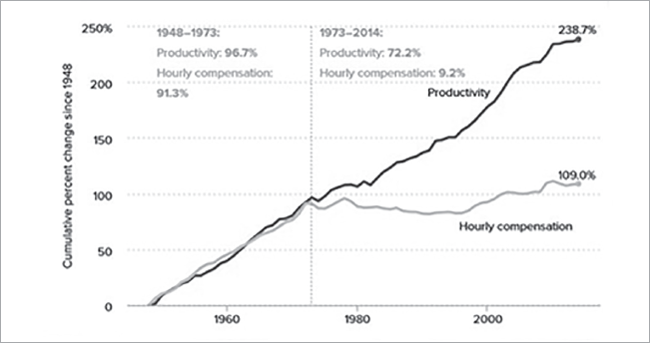

The pursuit of short-term shareholder value has also led to firms allocating almost all the gains that flowed from workers’ improvements in productivity to shareholders, including executives. This was a major shift from what had happened in prior decades when the economy had enjoyed steady broad-based growth. Thus, in the decades prior to 1980, compensation to workers and productivity had moved in lockstep. In the decades after 1980, shareholders were allocated almost all the gains (see Figure 8-2).25 Such a radical reallocation of resources was not dictated by any economic force in the marketplace. It was a conscious decision by executives to reallocate almost all gains to one class of stakeholder—shareholders, including themselves—at the expense of all others. As the Financial Times has pointed out, these collective decisions represent “an overwhelming conflict of interest.”26

Shareholder value thinking also led to other aberrant worker policies. Some 30 million workers in the United States are now bound by noncompete agreements that forbid them to leave their job to work for a competitor or to start their own competing business. Astonishingly, these agreements are “routinely applied to low-wage workers like warehouse employees, fast-food workers, and even dog sitters.” And the number of employees covered by such agreements is increasing rapidly.27 It is hard to see any possible justification for the proliferation of such agreements, except the predatory self-interest of the firms requiring them.

The overall result is a discouraged workforce. Only one in five workers is fully engaged in his or her work, and even fewer truly passionate about it.28 Worse, one in seven workers is actively undermining the firm’s goals.29 In a marketplace where success depends on rapid innovation, a disengaged workforce is a significant handicap.

![]()

The impact of shareholder value thinking has been particularly visible in the financial sector, which has faced the challenge of making profits in a context of low interest rates and tepid economic growth. Initially, the practices adopted were not illegal, even if they were not in the best interests of customers or society. Financial firms got involved in price gouging, seeking unusual ways to levy hidden charges on customers, particularly customers who were vulnerable. Some started gaming the system, by betting against securities that they themselves created. Firms instituted practices that resemble toll collecting, such as high-speed trading, using their position to extract charges, simply because of their position in the system. Some got involved in zero-sum proprietary trading in derivatives, with dubious social benefit and significant risk to society. These activities were encouraged by recruitment and compensation practices that made such activities a permanent part of the Wall Street corporate culture.30

From here, it was a small step for these practices to slide into illegality. Many major banks were involved in a wide range of illegal activities, including abuses in foreclosure, money laundering for drug dealers and terrorists, assisting tax evasion, and misleading clients with worthless securities. The net fines and legal expenses of these wrongdoings since 2008 are more than $300 billion.31

And the consequences of shareholder value thinking roll on. In 2015, Citibank and JPMorgan Chase were among five banks who admitted committing felonies. Barclays, Royal Bank of Scotland, and UBS also pleaded guilty to criminal misconduct in a major international scam affecting the way interest rates are set around the world. The banks were fined almost $6 billion, but no senior executives were punished, let alone sent to prison. Only lower-level banking officials were dismissed. Despite committing felonies, the banks continue with business as usual.32

In 2015, JPMorgan Chase again admitted wrongdoing and agreed to pay $307 million in fines. JPMorgan had steered its clients into its own high-price mutual funds and hedge funds, even where lower-cost comparable funds were available, and failed to disclose this to its clients, as required by the rules of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). According to the settlement, “undisclosed conflicts were pervasive.”33

In 2016, Wells Fargo admitted creating millions of fake accounts to boost apparent sales—practices that had been going on for more than a decade, despite multiple efforts by lower-level managers to protest the wrongdoing.34

Against this background, it’s hard to remember that, for several centuries, banks had generally been the bastions of morality. Today, insiders say that Wall Street’s culture focuses on short-term gains for itself, paying scant attention to the impact of its actions on other people or society. Financial managers no longer act as stewards of the financial system. The long tradition of finance as a principled, life-affirming, and morally worthy occupation is today less apparent than a scramble for cash.35

![]()

When activist shareholders talk of “unlocking value” from “underper-forming companies,” it’s easy to be seduced into thinking that some worthwhile social purpose is being served and to miss the consequences for real people and the lives of communities. For instance, let’s visit a company in Canton, Ohio, which has been manufacturing steel and bearings for almost a hundred years—the Timken Company. It’s the kind of firm where making things still matters. Over the years, unlike other companies in the region, Timken had not moved production to other countries where labor is cheaper. Instead, Timken had made huge capital investments in Canton.

Timken, for example, “spent $225 million to expand its steel mill, allowing Timken to innovate, dominate the market for customized steel products that enjoy high margins and stay ahead of rivals in South Korea, Japan and Germany. . . . While the steel industry may not seem high-tech, research and innovation are critical—about a third of the products TimkenSteel sells now were developed only in the last five years.”36 Timken was a family-run company that also put a sizable amount of its profits into Canton in the form of good wages and donations to schools and arts. By any measure, Timken was not only a good corporate citizen. It was also well managed and highly profitable. In the ten years prior to June 2014, Timken’s shares had been a good investment: It had outperformed the S&P 500—200 percent to 75 percent.

But that wasn’t enough for the financial sector, which was represented in this story by two actors. One actor, Relational Investors, was a Californian hedge fund that professed to create long-term growth in publicly traded, underperforming companies that it believed were undervalued in the marketplace.37 In fact, the modus operandi of such firms involves acquiring stakes in companies, pressuring them to make changes to “unlock value,” insisting that firms load themselves up with debt, buy back their own shares, return assets to shareholders, and drive their share prices higher. Then the hedge fund cashes in its profits and moves on to the next victim, with no thought for the financially fragile state in which it leaves the firm it has attacked.

Relational’s raid on Timken was a carefully orchestrated campaign, as it had carried out many times before, with accompanying infrastructure and finely tuned expertise to make the public case that Timken should be handing resources back to its shareholders. By contrast, Timken’s unsuspecting management had no experience with what was about to happen and was ill-prepared to deal with the media and legal onslaught.

Relational’s attack was successful. To enhance shareholder value, Timken was broken up into two companies: Timken and TimkenSteel. “All told, Relational acquired its stake at about $40 a share and sold at $70, reaping a 75 percent gain—$188 million.”38

In the process, Relational created no jobs and made no products or services for any real people. It simply extracted money that had been created over the years by the hard work of Timken’s managers and workers. Nor did Relational have to worry about what happens next to Timken, or to jobs in Canton. Within a year, Relational had sold all its shares in both Timken and TimkenSteel.39

Since then, the two Timken companies have not fared well in the stock market. The boost in the stock price engineered by Relational’s restructuring of Timken proved ephemeral. As of early 2017, Timken had lost more than a third of its value, while TimkenSteel had lost more than two-thirds of its value, during a period when the S&P 500 was rising.40

The second—and more surprising—actor in this story is the California State Teachers’ Retirement System, known as CalSTRS, representing teachers and their families in California—almost a million people. It is the eleventh largest public pension fund in the world. “CalSTRS owned only $16 million worth of Timken stock at the start of the fight, compared with $250 million for Relational, but it also has more than a billion dollars under management with Relational.”41 CalSTRS was the perfect front for Relational’s raid. “Timken was a risky target for Relational’s executives: They could be painted as Gordon Gekko types trying to make a fast buck by attacking a well-regarded, family-run company that had outperformed the stock market.”42 But having a pension fund like CalSTRS as a very public partner enabled Relational to convey the false narrative that in breaking up Timken, it was performing a virtuous public service: It was enabling the embattled schoolteachers of California to overcome the wicked plutocrats of Canton, Ohio.

It’s a troubling story. But none of the actors in it are to be blamed for what happened. The Californian teachers and their pension fund were doing their best to stay solvent in a difficult low-interest-rate environment; most of the teachers probably never heard of the impact of Relational’s campaign on the citizens of Canton, Ohio. Timken’s managers did their best to prevent their organization from being disemboweled, but a family-run company was no match for sophisticated raiders like Relational. And Relational itself can no more be blamed for its actions than a cat can be blamed for attacking a mouse. It’s in the very nature of a hedge fund to go after vulnerable companies with unsuspecting managers and then pump money out of them: That’s what a hedge fund does. What is iniquitous is a system that leads a whole society to pursue short-term monetary gains at the expense of long-term investment that delivers real products and services to real customers and grows the economy.

And Timken is not an odd exception. It’s just one of hundreds of such activist campaigns, which have been steadily increasing—from over 200 campaigns in 2013, to around 300 in 2015.43 Even the largest companies aren’t immune: A significant percentage of Fortune 100 and Fortune 500 companies have been targeted in the past few years.44 The total number of activist campaigns remains high, as activists now also target small and midsize companies.45

![]()

A principal goal of shareholder value thinking was to solve the supposed problem of “agency,” which is the risk that managers of corporations would act in their own interest, rather than the interests of the organization they were supposed to be managing. Ironically, shareholder value thinking has aggravated the problem of agency and turned it into a macroeconomic problem.

Even as nationwide corporate performance has been declining, execu tive compensation has been soaring. In the period 1978 to 2013, CEO compensation increased by an astonishing 937 percent, while the typical worker’s compensation grew by a meager 10 percent.46 The CEO-to-median-worker pay ratio of the 500 highest paid executives is now almost 1000:1 or $33 million, with 82 percent from stock-based pay.47

These egregious disparities are not simply the result of individual CEOs acting on their own. The problem is compounded by cronyism. Thus, in a study published in The Accounting Review, an astounding 62 percent of directors, who had a disclosed friendship with the CEO, said they would cut the budget for research and development in order to ensure the bonus for their friend, the CEO.48

The underlying rationale for shareholder value put forward by its initial academic champions was that giving stock to the CEOs would cause them to act as owners, patiently planning and working for the long-term good of the firm. What these professors failed to recognize was that, as the tenure of a CEO became increasingly short, executives would, unlike the permanent owner of a private firm, be tempted to grab what compensation they could while the going was good. Studies from the real world show that when executives are compensated with stock, they act very differently from private owners: They go straight for short-term gains for themselves—exactly what shareholder value thinking was meant to prevent.49

As Robin Harding in the Financial Times concludes, it is “time to stop thinking about corporate governance and executive pay as matters of equity and to regard them instead as a macroeconomic problem of the first rank.”50

![]()

For many years, it wasn’t obvious what the cost was to the real economy of all these aberrant behaviors, as the cost was hidden by the effects of financial engineering. Fortunately, a magisterial study of all U.S. companies has been carried out by Deloitte’s Center for the Edge. The conclusion? Over the period from 1965 to 2015, public corporations have been becoming steadily less productive. In the best measure of corporate performance—the rate of return on assets—U.S. firms are now performing only one-quarter as well as they were fifty years ago (see Figure 8-3).51

There’s a deeper problem, though. Financial engineering has led to excessive growth of the financial sector, which is now roughly three times larger than it was a few decades ago.52 Although this growth benefits those who work on Wall Street, from the point of view of the economy, it also results in a misallocation of financial and human resources.53 People and money that could have been deployed in activities benefiting real people are instead deployed in socially unproductive activities that are no more useful than gambling in Las Vegas.

The negative impact on the economy is startlingly large. A study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) quantifies the direct cost to U.S. economic growth of an oversize financial sector at around 2 percent of GDP per year.54 (See Figure 8-4.) In other words, if the financial sector were the proper size, the U.S. economy would be enjoying a normal economic recovery of 3 percent to 4 percent per year instead of the dismal 1 percent to 2 percent average of recent years. That’s a massive drag on the economy–over $300 billion in lost economic growth per year. In effect, the excessive financialization of the U.S. economy has become a major macroeconomic problem.

![]()

To return to our opening analogy, if these kinds of missteps were happening in the NFL, then everyone would realize that the “real game” of football had become utterly corrupted into gambling and manipulation. Everyone would be calling on the NFL Commissioner to intervene so that teams got back to playing the game of football.

Yet in business, when the “real game” of business has been utterly corrupted into various kinds of gambling and manipulation, business goes on as if nothing untoward is happening. Most regulators and legislators see nothing amiss.

Admittedly, some voices of alarm are now being heard: Business school professors Joseph L. Bower and Lynn S. Paine have denounced shareholder value thinking as “the error at the heart of corporate leadership.”55 Yet in the financial press, each incident of corporate missteps tends to be presented as an exception to the norm. “Bad things happen,” The Economist admits, but don’t blame shareholder value! “Outbreaks of madness in markets tend to happen because people are breaking the rules of shareholder value, not enacting them. This is true of the internet bubble of 1999–2000, the leveraged buy-out boom of 2004–08 and the banking crash. That such fiascos occur is a failure of governance and human nature, not of an idea.”56

It’s hard to look objectively at the evidence and exempt shareholder value thinking from blame by pointing to “failure of governance and human nature.” It is the very essence of shareholder value thinking itself that activates the failure of governance and the defects of human nature, by institutionalizing executives’ financial self-interest and legitimizing financial predators.57 (See Box 8-2, What Is True Shareholder Value?)

As the “exceptions to the norm” give no sign of ending, society has to recognize that the exceptions have become the norm and that something must be done, particularly when the recurring patterns of behavior have disastrous financial, social, and macroeconomic consequences.

![]()

While the broader issues of policy and societal change will be discussed in Chapter 12, the more pressing question for Agile leaders at all levels of the organization is to figure out how to protect Agile management from the noxious consequences of shareholder value thinking.

One obvious option? Just say no! Some CEOs have already spoken out. In addition to Jack Welch’s denunciation of “the world’s dumbest idea”:

![]() Vinci Group Chairman and CEO Xavier Huillard has called shareholder value thinking “totally idiotic.”58

Vinci Group Chairman and CEO Xavier Huillard has called shareholder value thinking “totally idiotic.”58

![]() Alibaba CEO Jack Ma has declared that “customers are number one; employees are number two, and shareholders are number three.”59

Alibaba CEO Jack Ma has declared that “customers are number one; employees are number two, and shareholders are number three.”59

![]() Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever, has denounced “the cult of shareholder value.”60

Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever, has denounced “the cult of shareholder value.”60

![]() John Mackey, CEO of Whole Foods, has condemned businesses that “view their purpose as profit maximization and treat all participants in the system as means to that end.”61

John Mackey, CEO of Whole Foods, has condemned businesses that “view their purpose as profit maximization and treat all participants in the system as means to that end.”61

![]() Marc Benioff, chairman and CEO of Salesforce, has declared that this still-pervasive business theory is “wrong. The business of business isn’t just about creating profits for shareholders—it’s also about improving the state of the world and driving stakeholder value.”62

Marc Benioff, chairman and CEO of Salesforce, has declared that this still-pervasive business theory is “wrong. The business of business isn’t just about creating profits for shareholders—it’s also about improving the state of the world and driving stakeholder value.”62

Larry Fink, the CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest institutional investor, has written to all the CEOs of the S&P 500 and called on them to present long-term strategies. Companies are “under-investing in innovation, skilled work-forces or essential capital expenditures,” he wrote.63

Sadly, though, most public corporations have yet to respond to the call. One reason is that they have succumbed to the siren call of the most appalling mechanism of finance engineering of them all: share buybacks.64 It is to this issue that we turn in Chapter 9.

Figure 8-1. Big Firms Are Job Destroyers.

Source: J. Wiens and C. Chris Jackson, “The Importance of Young Firms for Economic Growth” The Kauffman Foundation, September 13, 2015, http://www.kauffman.org/what-we-do/resources/entrepreneurship-policy-digest/the-importance-of-young-firms-for-economic-growth.

Figure 8-2. Disconnect Between Productivity and a Typical Worker’s Compensation.

Source: J. Bivens and L. Mishel, “Understanding the historic divergence between productivity and worker’s pay,” Economic Policy Institute, September 2, 2015, http://www.epi.org/publication/understanding-the-historic-divergence-between-productivity-and-a-typical-workers-pay-why-it-matters-and-why-its-real/.

Figure 8-3. Shift Index: Return on Assets of U.S. firms 1965–2015 (ROA).

Source: J. Hagel, J.S. Brown, M. Wooll, and A. de Maar, “The paradox of flows: Can hope flow from fear?” Deloitte University Press, December 13, 2016, https://dupress.deloitte.com/dup-us-en/topics/strategy/shift-index.html.

Figure 8-4: Financial Development Effect on Growth.

Source: J. Arcand, E. Berkes, and U. Panizza, “Too Much Finance,” IMF Working Paper WP/12/161, June 2012, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12161.pdf.

THE UNSOUND LEGAL CASE FOR

SHAREHOLDER VALUE

The notion that a corporation is a fiction is an illusion peculiar to macroeconomists, seemingly induced by the conclusion they are trying to prove. Not surprisingly, the notion has never been tested in a court of law.

Advocates of shareholder value thinking also argue that maximizing shareholder value is required by law. Yet law professor Lynn Stout has weighed in with her book The Shareholder Value Myth.1 It shows that shareholder value theory is not only counterproductive: It’s legally unsound. Shareholders don’t own the corporation:

What the law actually says is that shareholders are more like contractors, similar to debt-holders, employees and suppliers. Directors are not obligated to give them any and all profits, but may allocate the money in the best way they see fit. They may want to pay employees more or invest in research. Courts allow boards of directors leeway to use their own judgments. The law gives shareholders special consideration only during takeovers and in bankruptcy. In bankruptcy, shareholders become the “residual claimants” who get what’s left over.2

NOTES

1. L.A. Stout, The Shareholder Value Myth: How Putting Shareholders First Harms Investors, Corporations, and the Public (San Francisco: Berrett-Kohler, 2012).

2. J. Einhorn, “How Shareholders Are Hurting America,” Pro-Publica, June 27, 2012, http://www.propublica.org/thetrade/item/how-shareholders-are-hurting-america.

WHAT IS TRUE SHAREHOLDER VALUE?

“Today shareholder value rules business,” The Economist proclaimed in 2016, even though, as the article admits, shareholder value thinking has “fueled a sense that Western economies are not delivering rising prosperity to most people” and is seen as “a license for bad conduct, including skimping on investment, exorbitant pay, high leverage, silly takeovers, accounting shenanigans, and a craze for share buybacks, which are running at $600 billion a year in America.”1

“These things happen,” The Economist admits, “but none has much to do with shareholder value.” True shareholder value theory, according to the article, is something different, something pure, noble, and socially beneficent. True shareholder value is about investing in activities where “the capital employed by it made a decent return, judged by its cash-flow relative to a hurdle rate (the risk-adjusted return its providers of capital expected).”

Come again? If you didn’t quite understand the last sentence, you are not alone. As the book under review in The Economist article (Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies by McKinsey & Company) makes clear, most CEOs don’t have the financial smarts to master and implement that last sentence either.

Instead, what happens, as a recent study by Credit Suisse makes clear, is that most key investment decisions are based on the reputation of the executive making the investment proposal and the CEO’s “gut feel” about what should be done. Since the C-suite is hugely compensated for increases in the current stock price, guess what the “gut feel” tells the CEO? Decisions based on “shareholder value” are decisions that boost the current stock price.2

What rules business today is thus a degraded version of shareholder value theory—the idea that the purpose of a firm is to maximize shareholder value as reflected in the current stock price. The suggestion that most firms are basing decisions on “the capital employed by it” making “a decent return, judged by its cash-flow relative to a hurdle rate (the risk-adjusted return its providers of capital expected)” is a fantasy.

It is the short-term stock-price-oriented version of shareholder value that is presumed in daily financial news reporting, accepted as a go-to for any executive of a large public company, adopted as the modus operandi of activist hedge funds, endorsed by regulators, institutional investors, analysts, and politicians and often presented as simple common sense. It is this version of shareholder value that leads to the harmful consequences that The Economist article itself describes.

The concept of shareholder value, based on a careful calculation of “long-term shareholder value in comparison to a hurdle rate (the risk-adjusted return its providers of capital expected)” may be taught in business schools and promulgated in business textbooks like Valuation. But in the real world of business, it is the short-term stock-price-oriented version of shareholder value theory that is dominant.

How could it be otherwise? The very attraction of shareholder theory as articulated by Meckling and Jensen in their famous foundational article back in 1976 (“Theory of the Firm”) was that it offered a clear and simple measure of performance for everyday decision making in the organization. Managers could ask themselves: “Does this action boost quarterly profits and thus enhance the stock price? If yes, do it. If not, don’t.” It is this kind of clarity that has led to the embrace of shareholder value theory.3

Sadly, it is also this kind of clarity that has led to pervasive short-term thinking, cost-cutting, crippled innovation, and all the other noxious consequences of a preoccupation with shareholder value.

NOTES

1. “Analyse This: The Enduring Power of the Biggest Idea in Business,” The Economist, March 31, 2016, http://www.economist.com/news/business/21695940-enduring-power-biggest-idea-business-analyse.

2. Credit Suisse, “Capital Allocation—Updated,” June 2, 2015, https://plus.credit-suisse.com/researchplus/ravDocView.

3. M. C. Jensen, and W.H. Meckling, “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure,” Journal of Financial Economics 3, no. 4 (October 1976): 305–360, http://www.sfu.ca/~wainwrig/Econ400/jensen-meckling.pdf.

ADAM SMITH AND THE PHILOSOPHICAL ORIGINS

OF SHAREHOLDER VALUE THINKING

Although shareholder value theory in its current form took shape in the 1970s, its intellectual roots go back to Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations (1776), which spoke of “an invisible hand” that could miraculously turn selfishness from a vice into a virtue. A businessman might be intending his own gain, but in doing so, he was “led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. . . . By pursuing his own interest, he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.”

It is implausible that Adam Smith himself believed in the undiluted pursuit of self-interest, since he had written an entire book suggesting the opposite: The Theory of Moral Sentiments.1 Nevertheless, several centuries of economists have adopted the metaphor of “an invisible hand” and celebrated self-interest as the psychological foundation of modern economics. Elegant mathematical models—with a tenuous relationship to reality—have been developed to show that self-interest in business leads to the best of all possible worlds.

Friedman, Meckling, and Jensen thus took the preexisting metaphor of “an invisible hand” and proposed a license for enterprises to pursue unbridled self-interest across an entire society. Who can blame them for pushing the guiding metaphor of their profession to its logical conclusion? If self-interest in making money is a virtue, not a vice, why not go for it, flat out, hell for leather? Let businessmen single-mindedly pursue self-interest, and everyone will be better off!

Sadly, the theorists missed a key aspect of the fabric of reality: the Principle of Obliquity.2 In complex social situations, objectives are often best accomplished obliquely, not directly. Central planning is not the most effective way to run an economy. Frontal assault is rarely the best military strategy. The best way to become prime minister or president isn’t necessarily to declare that intent. The direct pursuit of happiness is not the best way to achieve happiness. And in business, the single-minded direct pursuit of profit isn’t necessarily the best way to make a profit.

The history of business over recent decades has come to resemble a concerted effort to ignore complexity and use linear thinking to discover direct shortcuts to success. Friedman, Meckling, and Jensen embraced the embryonic psychology of mainstream economics and missed counterintuitive peculiarities of the human mind and heart. They assumed that the best way to get to a complex goal is to head for it directly. It is not. Complex settings are messy and operate in a nonlinear fashion. The actions and intentions of others, and their reactions to our actions and intentions, are key components that we have to take into account in what we plan and do. The articulation or communication of a direct goal can lead to behaviors that prevent the achievement of that goal.

Where explicit articulation of a goal will result in a complex environment pushing back in the opposite direction, an oblique goal will generally be more effective. Making money is the result, not the goal, of a successful business. It was always thus, although the shift in power in the marketplace from seller to buyer has given fresh relevance to this truth.

The purpose of a firm, and the best way to make money—indeed the only sustainable way—is to create a customer. Shortcuts to prosperity by making money out of money are dangerous illusions. Prosperity comes from generating real goods and services for real human beings, not from gambling casinos set up to generate arbitrage from volatility.

NOTES

1. The Theory of Moral Sentiments begins with the following assertion: “How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortunes of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it, except the pleasure of seeing it.” By contrast, economists have taken the phrase in The Wealth of Nations about “an invisible hand” as the first step in the cumulative effort to build a model that proves that a competitive economy based on self-interest provides the largest possible economic pie.

2. J. Kay, Obliquity: Why Our Goals Are Best Achieved Indirectly (New York: Penguin, 2011).

THE UNANTICIPATED RISKS OF

SHAREHOLDER VALUE

The 1976 article by finance professors Meckling and Jensen is one of the most-cited but least-read business articles of all time. Replete with elaborate mathematics, it is often taken to provide a quantitative economic rationale for maximizing shareholder value, along with generous stock-based compensation to executives who followed the theory. The article, however, failed to deal with certain unanticipated risks to its central thesis.

The Meckling/Jensen article focused only on single decisions and the short-term impact of compensating executives with stock. The long-term impacts of pursuing shareholder value as reflected in the stock price were described as “important issues which are left for future analysis”—an analysis that the authors never got around to doing.

The article did envisage a risk that an executive might make “decisions which benefit him at the (short–run) expense of the current bondholders and stockholders.” The article was satisfied that this risk wouldn’t materialize: “If [the executive] develops a reputation for such dealings, he can expect this to unfavorably influence the terms at which he can obtain future capital from outside sources. This will tend to increase the benefits associated with ‘sainthood’ and will tend to reduce the size of the agency costs.”

However, the article didn’t foresee the risk that the “sainthood” involved in looking after the interests of shareholders might turn into ungodly combines of executives and shareholders against the interests of the corporation. Executives might conspire with shareholders and corporate raiders to extract value from the corporation at the expense of customers, employees, and the organization itself. Nor did the article perceive that this risk might materialize on a gargantuan scale.1

The theorists did not foresee the risk that if firms started to act on the basis that executives needed to be motivated to work on behalf of the shareholders for monetary gain, this might turn into a nightmarish self-fulfilling prophecy.2 Executives might, far from aspiring to the “sainthood” of looking after the long-term interests of shareholders, turn into grotesque caricatures of self-interest and greed, grabbing extraordinary compensation and pension benefits for themselves.3

The theorists didn’t worry about the risk to the organization itself, because to them an organization was a mere “legal fiction” (see Box 8-1). In the theoretical world inhabited by these academic economists, if one organization failed, it could be replaced by another. They didn’t perceive the risk that there might be very heavy economic and social costs in dismantling corporations and even whole sectors, along with the social capital embodied in them. Nor did they perceive the risk that shifting production to other parts of the world in search of lower labor costs in order to boost shareholder returns might cause irreparable damage to the national productive capacity, or that once lost, this productive capacity might not be easily retrieved.4

The theorists were even less worried about risks to employees, who were regarded as assets that were fungible, and even disposable, to serve the interests of capital: If employees lost their jobs, they could always seek employment elsewhere. “The employee is protected from coercion by the employer,” Milton Friedman complacently imagined, “because of other employers for whom he can work.”5 The theorists never imagined that there would come a time when tens of millions of U.S. employees—even low-level employees—would be bound by noncompete agreements that forbade employees to leave their job to work for a competitor or to start their own competing business.6

Nor did the theorists foresee the risk that the extraction of value from corporations might become so great that there would be few “other employers” offering quality employment. Nor did they envisage that if this process was continued over decades by most publicly owned corporations, the impacts would become macroeconomic in scale, and that there would eventually be a shortage of customers for real goods and services and limited opportunities to invest in. In the language of the macroeconomists, there would be a “lack of demand,” according to Friedman. The economy could thus be facing secular economic stagnation.7

Nor did the theorists worry about the possibility that there would be an unholy alliance between shareholder value theory and top-down command-and-control management. Once a firm embraced maximizing shareholder value and the current stock price as its goal, and lavishly compensated top management to that end, the C-suite would have little choice but to deploy command-and-control management, because making money for shareholders and the C-suite is inherently uninspiring to employees. The C-suite would have to compel employees to obey, even if this meant that employees would become dispirited. The authors didn’t worry that dispirited employees might become a critical constraint in an economy that would depend on innovation from engaged knowledge workers. How firms were managed was not a matter of much interest to academic economists.

Nor did these economic theorists recognize the risk that if corporations didn’t invest in training and retraining their employees and merely shifted work to wherever labor costs were currently lowest in order to boost immediate returns to shareholders, there might come a day when there was an inadequate pool of trained workers from which they would draw on for the creation of future businesses.8

Nor did the theorists worry too much about customers. If customers didn’t like what corporations were offering they could, as Milton Friedman had written, take their business elsewhere: “The consumer is protected from coercion by the seller because of the presence of other sellers with whom he can deal.”9

The theorists didn’t perceive the risk that if most corporations in a country favored shifting resources to shareholders instead of investing in innovation for customers, customers might become dissatisfied and take their business “elsewhere” to corporations who did care about them, so that eventually the dynamism of entire industries or even a whole national economy might be compromised.10

Nor did they perceive the risk of damage to communities by closing plants in order to benefit from the lower cost of labor elsewhere in the world and thereby boost returns to shareholders. They assumed that “the magic of the marketplace” and the process of “creative destruction” would heal any damage that a short-term extraction of value might cause. They didn’t envisage the risk that the extraction of value might reach such a scale that there would be insufficient resources available to the economy as a whole to heal the damage to communities caused by the short-term extraction of value.11

Nor did they foresee the risk that diverting resources to shareholders and executives from investments in the future might reach such a scale that the capacity of the economy to grow and compete in the international marketplace or provide quality livelihood for all its citizens might be compromised.12 They did not anticipate the possibility that the economy would ever be in a situation where it would only be able to sustain an appearance of prosperity through vast infusions of cheap money from the central bank.

Nor did they foresee the risk that by creating strong financial incentives to do the easy thing of low value to the real economy (i.e., increasing the stock price) while creating structural disincentives to do the difficult thing of high value to the organization and the real economy (i.e., grow the business by investing in market-creating opportunities), most executives would spend their efforts in self-interested activities of low value to the organization and the real economy.

Yet these were the very risks that materialized over the next four decades.

Friedman was famous for pointing to the fallacy of good intentions. “Concentrated power,” he wrote in Capitalism and Freedom, “is not rendered harmless by the good intentions of those who create it.” Friedman was referring, of course, to government, but his dictum has also turned out to be a prophetic critique of his own legacy in the private sector.

In his celebrated career, Friedman himself had great influence on economic policy and management practice. But with great influence comes great responsibility. Friedman’s doctrines have had consequences that are the opposite of what he intended. Friedman was an honorable man. His intentions were good, but the consequences of what he wrote are not rendered harmless by his good intentions. His admirers claim that he “rescued the U.S. economy” and provided “a cure for capitalism.”13 Unfortunately, we can see with the wisdom of hindsight that the cure has turned out to be worse than the disease.

NOTES

1. S. Denning, “How CEOs Became Takers, Not Makers,” Forbes.com, August 18, 2014, http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2014/08/18/hbr-how-ceos-became-takers-not-makers/; S. Denning, “From CEO Takers to CEO Makers: The Great Transformation,” Forbes.com, August 20, 2014, http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2014/08/20/from-ceo-takers-to-ceo-makers-the-great-transformation/.

2. M. C. Jensen, and W. H. Meckling, “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs, and Ownership Structure,” Journal of Financial Economics 3, no. 4 (October 1976): 305–360. They put forward the absurd view that the executive’s motivation is solely pecuniary: In due course, this assumption became a horrifying self-fulfilling prophesy.

3. S. Denning has written extensively on this subject; see “Retirement Heist: How Firms Plunder Workers’ Nest Eggs,” Forbes.com, October 19, 2011, http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2011/10/19/retirement-heist-how-firms-plunder-workers-nest-eggs/; “GE Discusses Retirement Heist,” Forbes.com, October 21, 2011, http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2011/10/21/ge-discusses-retirement-heist/Heist Part 3, Forbes.com, October 22, 2011, http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2011/10/22/retirement-heist-part-3-ellen-schultz-replies-to-ge/; and “How Your Pension Got Turned into Scotch or Cheese,” Forbes.com, April 22, 2013, http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2013/04/22/sorry-about-your-pension-scotch-cheese-or-golf/.

4. See the discussion in Chapter 7 and in S. Denning, “The Surprising Reasons Why America Lost Its Ability to Compete,” Forbes.com, March 10, 2013, http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2013/03/10/the-surprising-reasons-why-america-lost-its-ability-to-compete/.

5. M. Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), 14.

6. O. Lobel, “Companies Compete but Won’t Let Their Workers Do the Same,” New York Times, May 4, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/04/opinion/noncompete-agreements-workers.html.

7. L. Summers, “U.S. Economic Prospects: Secular Stagnation, Hysteresis, and the Zero Lower Bound,” Business Economics 49, no. 2 (2014), http://larrysummers.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/NABE-speech-Lawrence-H.-Summers1.pdf. At first, Summers argued that the problem was one of demand. In a later article, he suggested that “supply-side chokes” were also part of the problem. See Tomas Hirst, “Larry Summers Admits He May Have Been Wrong on Secular Stagnation,” Business Insider, September 9, 2014, http://www.businessinsider.com.au/larry-summers-admits-he-may-have-been-wrong-on-secular-stagnation-2014-9.

8. Denning, “The Surprising Reasons Why America Lost Its Ability to Compete.” Models based on the “invisible hand of the marketplace” and “perfect competition” are turning out to be obsolete mantras, rather than useful guides to action. There are currently 4 million unfilled jobs in the United States.

9. Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom, 14.

10. See Chapter 7 and Denning, “The Surprising Reasons.”

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. S. Denning, “Milton Friedman and the Fallacy of Good Intentions,” Forbes.com, August 1, 2013, https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2013/08/01/milton-friedman-and-the-fallacy-of-good-intentions/.