9.

THE TRAP OF SHARE BUYBACKS

Share buybacks have become a kind of corporate cocaine that induces a temporary feeling of invincibility but masks weakness and vacuity.

—THE ECONOMIST1

In 1787, Empress Catherine II of Russia made an unprecedented six-month trip to Crimea, the “New Russia,” with her court and some foreign ambassadors. The area had been devastated by war. Amid fears of new hostilities, the purpose of the trip was to impress on Russia’s allies how prosperous the region had become after rebuilding the region and bringing in Russian settlers.

The Empress was accompanied on the trip by the official who had been responsible for rebuilding the region and bringing in Russian settlers. The official, Grigory Potemkin, happily combined this official role with his unofficial function of bedroom companion and lover of the sex-hungry Empress.

Potemkin’s problem on the visit was that the reconstruction of the area was not as far along as desired. Not wanting to disappoint the wishes of his imperial mistress, and being an energetic fellow, he hit upon an ingenious scheme. Why go to the bother of generating actual prosperity when prosperity could be simulated?

Potemkin had a team of workers develop some portable villages. Prior to the arrival of the Empress’s barge, Potemkin’s men, dressed up as peasants, would show up at the site and assemble a village. At night, in the midst of the barren territory, the fake settlements with their glowing fires would comfort the Empress and her foreign entourage. Once the Empress’s barge had departed, the village would be disassembled and rebuilt downstream for the imperial visit the next evening.

The stratagem was a personal success for Potemkin. The Empress was sufficiently pleased with his multiple services that he solidified his hold on power. For Russia, however, the outcome was less happy. The visiting ambassadors detected the difference between the real and the fake villages and Potemkin’s deception was condemned by his political opponents. Shortly after the imperial visit, the region was plunged into a war between Russia and the Ottoman Empire.

![]()

Fast-forward a couple of hundred years and we can see how Potemkin’s tactics have been adapted to the modern world of corporate finance through the use of share buybacks.

The man who brought the debacle to public notice is Bill Lazonick, a strong-minded economics professor who has been working for several decades on the role of innovative business enterprises in generating productivity. His work has focused on the growing financialization of the U.S. economy, taking into account broader historical and global perspectives such as the British Industrial Revolution, Japan, and China. He set out to construct a rigorous theory of economic growth, grounded in the microeconomics of the innovative enterprise. Lazonick has systematically challenged the faith of mainstream economists in the magic of the marketplace. Over time, he became a leading critic of mainstream economic thinking and current business practices.

In 1993, after the publication of three books in the three previous years, Lazonick made the unusual academic move of leaving a tenured position at an elite private university for one at a regional public institution, University of Massachusetts Lowell, so that he could have more freedom to pursue innovative thinking.

For several decades, Lazonick’s work was known mainly among academic economists. But in 2014, a breakthrough came. Lazonick’s work was featured in an article in Harvard Business Review. It presented the business world with astonishing news: Many major public corporations are engaged in buying back their own shares to an extent that constitutes stock-price manipulation on a macroeconomic scale.2

It was hard to argue with Lazonick’s conclusions, which were based on decades of detailed data collection and economic analysis. Other mainstream journals picked up the theme. The Economist called share buybacks “an addiction to corporate cocaine.” Reuters called it “self-cannibalization.” The Financial Times called it “an overwhelming conflict of interest.” In March 2015, Lazonick’s article won the HBR McKinsey Award for the best Harvard Business Review article of the year.3

How had so many of the biggest and most respected companies in the world gotten involved in stock-price manipulation on such a massive scale? Why is it still tolerated by regulators?

It’s simple, Lazonick explains. Once firms began in the 1980s to focus on maximizing shareholder value as reflected in the current share price, the actual capacity of these firms to generate real value for the organization and its shareholders began to decline as cost-cutting, dispirited staff, and limited capacity to innovate took their toll. Thus, the C-suite faced a dilemma. They had promised increasing shareholder value, and yet their actions were systematically destroying the capacity to create that value. What to do?

They hit upon a wondrous shortcut: Why bother to create new value for shareholders? Why not simply extract value that the organization had already accumulated and transfer it directly to the shareholders (including themselves) by way of buying back their own shares? By reducing the number of shares, firms could, through simple mathematics, boost their earnings per share. The result was usually a bump in the stock price—and short-term shareholder value.

Of course, by diverting important resources to boost the stock price, the tactic ran the risk of further hindering the firm’s capacity to innovate and generate fresh value for customers in future. But why worry about that? With luck, by the time it became apparent that the firm had undermined its long-term capacity to add real value to customers, the executives responsible for the decisions would be safely retired, with bonuses already paid. The loss of capacity to create value would be someone else’s problem.

There was just one snag. Jacking up the share price with large-scale share buybacks would constitute stock-price manipulation and hence would be illegal. But no problem! In 1982, the Reagan administration was happy to remove the impediment and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) instituted Rule 10b-18 of the Securities Exchange Act.

Naturally, the SEC didn’t announce that stock-price manipulation was being legalized. That would have created a political outcry. Instead, they passed a very complicated rule that made it seem that stock-price manipulation was still illegal, but provided protection to firms so that it would be hard to detect and almost invulnerable to legal challenge.

The complex rule that the SEC came up with is the following. Bear with me if you find the rule hard to understand. That of course is the whole point of the language: to make it hard to understand.

Under the rule, a corporation’s board of directors can authorize senior executives to repurchase up to a certain dollar amount of stock. After that, management can buy more company’s shares provided that, among other things, the amount did not exceed a “safe harbor” of 25 percent of the previous four weeks’ average daily trading volume. Since companies are not required to report daily repurchases, the SEC has no way of determining whether a company has breached the 25 percent limit without a special investigation. The rule preserves the illusion that stock price manipulation is still illegal. But in practice companies can repurchase their shares on the open market with virtually no regulatory limits. Even better: Since the share purchases are happening in the background, the public can’t see what is going on.

And so the floodgates opened. The resulting scale of share buybacks is mind-boggling. Over the years 2006–2015, Lazonick’s research shows that the 459 companies in the S&P 500 Index that were publicly listed over the ten-year period expended $3.9 trillion on share buybacks, representing 54 percent of net income, in addition to another 37 percent of net income on dividends. Much of the remaining 10 percent of profits are held abroad, sheltered from U.S. taxes. The total of share buybacks for all U.S., Canadian, and European firms for the decade 2004–2013 was $6.9 trillion. The total share buybacks for all public companies in just the United States for that decade was around $5 trillion.4

Theoretically, the SEC could launch investigations and intervene to prevent what is obviously share-price manipulation. But the SEC has been inactive. “The SEC,” says Lazonick, “has only rarely launched proceedings against a company for using them to manipulate its stock price.”

In fact, the SEC recently declared itself powerless to do anything about the problem. Thus, in July 2015, when Tammy Baldwin, the Democratic Senator from Wisconsin, asked the SEC head appointed by the Obama administration, Mary Jo White, to look into the issue of stock-price manipulation resulting from share buybacks, White replied that the SEC could not consider the issue because of the protection offered by Rule 10b-18. The prospects of changing that ruling in the current investor-friendly administration seem even more remote.5

True, not all share buybacks are bad. They can make sense “when the share price is—truly—below the intrinsic value of the productive capabilities of the company and the company is profitable enough to repurchase the shares without impeding its real investment plans.”6

But these “constitute only a small portion of modern buybacks,” says Lazonick. “Surgical interventions with private tenders are the exception.” Most of the trillions of dollars in share buybacks have been made on the open market, often when the share price is high. Open-market share buybacks generally “come at the expense of investment in productive capabilities.”7

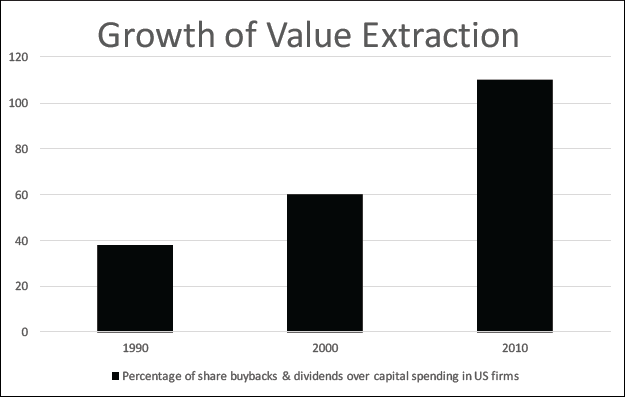

Share buybacks not only continue on a massive scale. They are increasing. The Financial Times reported that in 2015, U.S. companies unleashed “a share buyback binge. . . . Now the market stands on the cusp of seeing a record of more than $1 trillion returned to shareholders in the form of dividends and stock repurchases this year.” This is happening at a time when share prices are at record highs.8 (See Figure 9-1.)

The practice of share buybacks has been further enabled by the actions of the central bank since 2008 in providing cheap money in almost unlimited quantities to large corporations via the banking system. Big corporations could thus borrow vast amounts of money at practically no cost and use the loans to fund stock buybacks for the benefit of the shareholders and their executives.

The ostensible goal of the central bank’s action was to stimulate the economy out of the Great Recession. But now, nine years later, low-cost money is still available and the economy continues to sputter along in a state of secular economic stagnation.

Although the poet Wallace Stevens, in a moment of fancy, compared money to poetry, money is more often like information. When money can be obtained in large quantities at zero interest rates over long periods, it fosters the illusion that money is limitless, which leads both governments and businesses astray. The principal beneficiaries of the central bank action have been, not the population as a whole, but rather those who own shares. The stock market soars, and traders and the owners of assets exult. The result, however, is Potemkin prosperity, not the real thing.

![]()

Principal beneficiaries of share buybacks include activist shareholders. For instance, in recent years, activist hedge funds, who played absolutely no role in the success of firms over the decades, have purchased large amounts of their stock and then pressured the companies to implement huge buyback programs. The transactions transferred vast amounts of resources to the activists with no gain to the real economy.

Rather than investing resources in creating new value for customers with market-creating innovations, share buybacks are siphoning off resources to hand back to shareholders. The suggestion that the siphoned-off resources are being used elsewhere in the economy to create jobs stretches credibility. It ignores the reality that the resources are mostly deployed to finance other value-extraction schemes.

Share buybacks, Lazonick points out, ignore the legitimate claims of “other participants in the economy who bear risk by investing without a guaranteed return. . . . As risk bearers, taxpayers, whose dollars support business enterprises, and workers, whose efforts generate productivity improvements, have claims on profits that are at least as strong as the shareholders.”9

In effect, many public companies have become giant “reverse Ponzi schemes.” Thus, a Ponzi scheme attracts investments into a firm on the false premise that it is a valuable company. By contrast, a reverse Ponzi scheme takes a valuable firm and systematically extracts value from it. The firm appears to be making profits even as it systematically destroys its own earning capacity by handing over resources to shareholders.

The Challenge for Public Policymakers

The systematic extraction of value from corporations on a macroeconomic scale isn’t an issue of a few misguided individual CEOs or occasional aberrations from the norm. It’s one of fundamental institutional failure. CEOs are extracting value from their firms and helping other CEOs do the same thing. Boards are giving the C-suite incentives to do it. Business schools are teaching them how to do it. Institutional shareholders have been complicit in what the CEOs are doing. Regulators search for individual wrongdoers, usually those below the C-suite, while remaining blind to systemic failure. Central bankers indirectly fund the operation and close their eyes to the economic consequences. See Figure 9-2.

It is time for society’s leaders to fix a flawed system. A systemic solution goes well beyond the obvious step of repealing the “safe harbor” provided by Rule 10b-18 of the Securities Exchange Act, which effectively enables big corporations to pursue stock price manipulation on a massive scale. Resolving the problem involves many institutions: Corporations, corporate boards, investors particularly institutional investors, legislators, regulators, business schools, and central banks all need to think and act differently.

The change must start with Wall Street itself. As of mid-2017, there were some signs that this was already happening. Investors now are punishing companies that have focused on share buybacks. “Infatuation with buybacks has ended for both companies and investors,” David Kostin, Goldman’s chief U.S. equity strategist, said in a note to clients. “Experience shows that firms repurchasing shares at extremely high valuations regret those actions when the stock price inevitably de-rates.”10 (We will come back to these issues in Chapter 12 and Box 12-2.)

The Challenge for Agile Leaders in Dealing with the Stock Market

The more pressing challenge for Agile leaders is how to deal with continuing pressures to shift resources from investment into share buybacks. The answer lies in recognizing that going along with these pressures is a choice, not a necessity. Thus, some firms have made it explicit from the outset that they will not be playing the value-extraction game. Amazon is the most prominent example. It never focused on short-term shareholder value. At Amazon, shareholder value is the result, not the operational goal. Amazon’s operational goal is market leadership. Although its short-term profits have been variable, the stock market has handsomely rewarded Amazon’s long-term strategy.

“We first measure ourselves,” says Amazon’s CEO, Jeff Bezos, “in terms of the metrics most indicative of our market leadership: customer and revenue growth, the degree to which our customers continue to purchase from us on a repeat basis, and the strength of our brand. We have invested and will continue to invest aggressively to expand and leverage our customer base, brand, and infrastructure as we move to establish an enduring franchise.”11

Amazon obsesses over customers, not shareholders. “From the beginning, our focus has been on offering our customers compelling value.” Long-term shareholder value, says Bezos, “will be a direct result of our ability to extend and solidify our current market leadership position. The stronger our market leadership, the more powerful our economic model. Market leadership can translate directly to higher revenue, higher profitability, greater capital velocity, and correspondingly stronger returns on invested capital.”12

And it is not impossible to commit to customer value in midstream. For instance, on his first day as CEO of Unilever, Paul Polman warned his shareholders that he was not going to maximize shareholder value as reflected in the stock price. “Immediately, the Dutch-born Polman put his shareholders on notice,” writes Forbes contributor Andy Boynton. “He declared that they should no longer expect to see quarterly annual reports from the company, along with earnings guidance for the stock market. Unilever, he explained, was now taking a longer view. CEO Polman went a step further, urging shareholders to put their money somewhere else if they don’t ‘buy into this long-term value-creation model, which is equitable, which is shared, which is sustainable. I figured I couldn’t be fired on my first day,’ Polman later said. Unilever’s share price initially sank, but eight years later, Polman is still the CEO. Its stock price has soared and Unilever is prospering by delivering real value to real customers in a sustainable way.”13

A key step is to educate investors that a focus on short-term returns and the wholesale use of share buybacks actually destroys shareholder value. Amazon, Unilever, and Berkshire Hathaway have made clear to investors that they won’t be playing the shareholder value game. Instead of being punished for ignoring the short term, these firms have been rewarded with strong investor support.14 See Figure 9-3.

Much of the pressure to manage for the short term is thus self-inflicted. To a large extent, business leaders get the investors that their behavior attracts. The first step in emancipating their shareholders from indulging in “corporate cocaine” is to emancipate themselves from it.15

The Challenge for Agile Managers Within the Corporation

The pressures within public corporations to devote resources to share buybacks can pose serious headwinds on Agile management. While one part of the corporation may be doing its utmost to add value for customers through Agile management, another part—the C-suite—may be extracting resources to buy back shares in response to pressures from the stock market.

When leaders succumb to these pressures, corporations become schizophrenic. As more resources are shifted into share buybacks, there are insufficient resources to support investment in innovation. And because there is insufficient innovation, there is a need for more share buybacks. In a world in which boosting the current stock price is the overriding concern, investments in market-creating innovations for customers are often what gets cut.

For the Agile manager in a public corporation, the challenge is to see what can be done to insulate the firm’s Agile journey from these pressures. The first step is for managers to educate themselves on the nature and extent of the problem. Many Agile managers are oblivious to what is going on in the organization beyond their immediate sphere of influence. Then they are surprised when an edict comes down from the C-suite shifting resources away from needed innovation in an effort to boost the current stock price.

As a practical matter, Agile managers must face the reality that unless they can wean the C-suite from the “corporate cocaine” of share buybacks and disabuse them of the merits of shareholder value thinking, the life of an Agile transformation within the firm is unlikely to be happy or long. The stakes are high: Either Agile management will take over the whole organization, or shareholder value thinking will crush Agile management.

Agile managers need to make the case that if the firm takes care of customers, shareholders will also do much better. The opposite simply isn’t true: If a firm focuses on taking care of shareholders in the short term, customers don’t benefit and, ironically, the gains for shareholders are usually ephemeral. It’s the real market of providing goods and services to real customers that creates a sustainable future in a way that exploiting short-term financial opportunities can never achieve. Agile management thus produces meaning and motivation for organizations along with a real future. Agile managers must educate the C-suite that “corporate cocaine” may feel good in the short term but it has horrendous consequences for the firm’s health.

If Agile managers are to win these battles within the organization, they must also understand and deal with the cost-oriented economics through which shareholder value thinking has become embedded in day-to-day decision making. What’s involved in doing that is the issue to which we now turn in Chapter 10.

Figure 9-1. Growth of share buybacks.

Figure 9-2. The vicious cycle of value extraction.

Figure 9-3. The virtuous circle of long-term value creation.

DEFENDING SHARE BUYBACKS

Executives give five main justifications for open-market share buybacks: “We’re helping shareholders who own the company.” Or, “We’re preventing shareholder dilution.” Or, “We’re buying when prices are low to strengthen the company.” Or, “We have run out of good investment opportunities.” Or, “The shareholders will use the money to create jobs.” None of these justifications are plausible.

![]() “Creating value for shareholders”? Wrong! Most open-market share buybacks provide temporary wins but systematically kill long-term value for shareholders. They are extracting value, not creating it.

“Creating value for shareholders”? Wrong! Most open-market share buybacks provide temporary wins but systematically kill long-term value for shareholders. They are extracting value, not creating it.

![]() “Signaling confidence in the company’s future”? How can this be so, when, as Lazonick points it, “over the past two decades major U.S. companies have tended to do buybacks in bull markets and cut back on them, often sharply, in bear markets”? What sort of a game is it when executives “buy high and, if they sell at all, sell low”? The answer is clear: share-price manipulation.

“Signaling confidence in the company’s future”? How can this be so, when, as Lazonick points it, “over the past two decades major U.S. companies have tended to do buybacks in bull markets and cut back on them, often sharply, in bear markets”? What sort of a game is it when executives “buy high and, if they sell at all, sell low”? The answer is clear: share-price manipulation.

![]() “Offsetting the dilution of earnings from employee stock options”? Bad idea! This defeats the purpose of using stock options in the first place—namely, to encourage long-term performance.

“Offsetting the dilution of earnings from employee stock options”? Bad idea! This defeats the purpose of using stock options in the first place—namely, to encourage long-term performance.

![]() “Nowhere to invest”? A smokescreen! This pretext signals that chief executives are not performing their principal function of discovering new investment opportunities. In effect, executives are setting aside the hard work of creating sustained innovation and simply making money for themselves and their colleagues with the stroke of a pen. Top management, in effect, is not doing its job.

“Nowhere to invest”? A smokescreen! This pretext signals that chief executives are not performing their principal function of discovering new investment opportunities. In effect, executives are setting aside the hard work of creating sustained innovation and simply making money for themselves and their colleagues with the stroke of a pen. Top management, in effect, is not doing its job.

![]() “Shareholders will use the money to create jobs elsewhere in the economy”? Disingenuous! In an economy driven by money chasing money, there are simply not enough public corporations creating jobs through investing in innovation to absorb these trillions of dollars. For the most part, the money adds to the stock of money chasing money, thus paving the way for the next financial crash.

“Shareholders will use the money to create jobs elsewhere in the economy”? Disingenuous! In an economy driven by money chasing money, there are simply not enough public corporations creating jobs through investing in innovation to absorb these trillions of dollars. For the most part, the money adds to the stock of money chasing money, thus paving the way for the next financial crash.

Practices like share buybacks generate inauthenticity in executives, filling their world with encouragements to suspend moral judgment. They receive incentive compensation to which the rational response is to game the system. And since they spend most of their time trading value rather than building it, they lose perspective on how to contribute to society through their work. Customers become marks to be exploited and employees become disposable resources.

Enlightened self-interest dictates that firms break out of the vicious cycle of value extraction (Figure 9-2) and embrace a virtuous circle of value creation (Figure 9-3).