For the past ten years, VersionOne software , a provider of agile project tools, has performed a “State of Agile”1 survey. In 2009, the survey listed “management opposed to change,” “loss of management control,” “team opposed to change,” and “lack of discipline” as top challenges to agile adoption. In the ninth survey, five years later, top barriers to adoption are “lack of management support,” “company philosophy at odds with agile,” “external pressure to follow traditional waterfall processes,” and “a broader organizational or communication issue.” After five years of widespread adoption, it’s still culture and management that obstruct agile evolution.

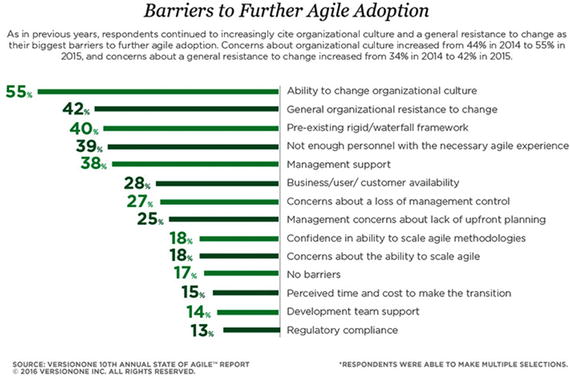

As illustrated by this graphic from the ninth State of Agile survey2 (Figure 2-1), every issue cited here, with the possible exception of inexperience with agile, is a management or cultural issue. It’s management that sets the tone of culture and drives organizational communication, that sponsors agile transition (or doesn’t), that applies pressure to follow waterfall or systems development cycle (SDLC) processes , and that budgets for training (or doesn’t).

Figure 2-1. Barriers to further agile adoption

Why Culture Matters

My favorite definition of culture is the simplest: “the way we do things here in order to succeed.”3 Other concise definitions are “the personality of the organization” or “the operating system of the enterprise.”

Less concise, but more nuanced, is Edgar Schein’s4 definition:

A pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group learned as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, that has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way you perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems.

Schein’s definition, though academic, highlights a few important points for agile consultants. Cultures grow and adapt, based on external conditions. They may not adapt at the speed we, as change agents, would hope, but the General Motors (GM) of today is certainly different than the GM of 1960, or even 1990. That culture only must have “worked well enough (my emphasis) to be considered valid” shows that organizations often make compromises and accept inefficiencies because they’re “good enough.” Finally, these cultural norms are swiftly taught to new members to influence the “correct” way they “perceive, think and feel.” Schein’s definition reminds us that while culture is tenacious, intentional, and influential, it’s also adaptable and open to improvement.

I often hear other agile consultants complain that the culture is broken at a certain client’s organization. Efforts to adopt agile will often falter or fail, and many consultants indict “dysfunctional” firms that are too bureaucratic, too political, or too change-resistant to successfully evolve. I’m not a proponent of the “broken culture” philosophy. My observation is that cultures evolve because the participants want things that way. They value the outcomes of the current culture, which are often measured personally: my title, my authority, my workload, my commitment level, my security and stability. An enterprise judged as dysfunctional at adopting agile is often highly accomplished at protecting rank, sheltering employees from disruption, offering a stable and secure environment, minimizing personal accountability or consequence, and blocking change. They may be dysfunctional from an agile perspective, but their evolution to their current cultural norms wasn’t an accident; it was the result of conscious decisions by the entire community of what is valued, what is acceptable, and what is not. As consultants, our work is observational and diagnostic, not judgmental.

Another widely held belief is that “people naturally resist change.” There’s clearly truth to this, as all consultants have experienced, but it’s ascribing resistance to the wrong motivation. People don’t resist change when they get a raise, or win a prize, or find a great new job. They resist not change itself but the potential risk and loss it brings. From the executive suite to the newest rookie on staff, when rumblings of change begin to circulate, most people are immediately assessing the potential damage to their standing, reputation, power, workload, compensation, and accountability. The friction exists, in my view, not merely due to some irrational resistance to any change. People rationally calculate the risks of upheaval and loss created by change, compared with the stability and personal rewards of the status quo.

The Cultural Change Imperative

Whether starting at the top with an executive conversation about agile transformation in the enterprise, or beginning at the team level with a single scrum or agile team, the State of Agile studies make it clear that our greatest challenges as agile consultants are managerial and cultural. When we engage at the software team level, for example, we learn about the disconnections, miscommunications, stretched resources, and strained relationships that developers experience. At the executive level we learn about the challenges of misaligned priorities, legacy technologies and skills, failed projects, and unmet expectations. When 43% of survey respondents claim that cultural incompatibility with agile is the key barrier to adoption, and 38% cite lack of management support, it becomes obvious that, if the organization is seeking increased agility, a strategic, consultative approach is called for. Team-based coaching will always be essential to organizations starting their agile journey, but it is not sufficient if the aim is agility across the enterprise.

Executives understand that they are in jeopardy and must change. In the oft-quoted 2010 IBM study “Capitalizing on Complexity ,”5 a survey of over 1,500 chief executive officers (CEOs) in the United States, over 80% said they expected their organization to experience more volatility, more uncertainty, and more complexity in the next few years. Some 60% are experiencing high complexity now, and 79% expect to see more. Most alarming, in my view, is that while 79% expect higher complexity, only 48% feel prepared to deal with it.

Yet some organizations are thriving in these tumultuous times. IBM calls these the “Standouts.” This small percentage of CEOs are thinking about their business differently. According to IBM’s survey results, the Standouts have three key attributes that account for their leadership in turbulent conditions.

Creative leadership

Reinventing customer relationships

Building operating dexterity

The connection of these traits to agile philosophy is clear. Creativity, not decisiveness or strong leadership, is now recognized by executives as the driver of competitive advantage. Drastically revamping the organization, enabling innovation, inviting customers and teams into the conversation—these all correlate directly to agile’s emphasis on people-focused, collaborative, customer-centric practices.

Later in this chapter, we’ll discuss in depth the reinvention of customer relationships, driven by Internet-enabled forms of customer intimacy. The customer may be an e-mail address, but the enterprise’s knowledge of customer habits and preferences creates a new kind of familiarity. The feedback and data generated by a transaction are as valuable as the transaction itself, as the firm builds millions of interactive relationships with complete strangers. Netflix knows what I want from my transaction history and that of my demographic cohort, as does Amazon. Google knows what I want explicitly, as I tell them so when I search. The CEOs whom IBM selected as Standouts focused on using analytics, driven by these streams of data, to increase their customer obsession.

The data, unfortunately, has little value if the enterprise can’t respond. Organizational dexterity is another way of saying enterprise agility. Dexterity, the ability to change in reaction to events and circumstances, is a strategic goal that far transcends the software development practice. For information technology (IT), it requires re-imagining data centers, cloud, hybrid infrastructures, and mobility, as well as new development methods. As agility spreads from software to IT infrastructure and then across the enterprise, thoughtful executives will be reimagining their entire value chain to incorporate agility everywhere. The agile consultant, by embodying the agile principles and helping translate them from product development to strategic thinking, has the opportunity to reshape enterprise culture and help teams and organizations prepare for tomorrow's tempestuous business climate.

Adapting Agility to Different Cultures

Focusing on IT for a moment, many agile consultants have experienced the complexity of reconciling the iterative, experimental nature of agile software development with the stability , security, and support concerns of IT infrastructure teams. We’ll talk about DevOps and other approaches for IT to increase agility, but in the early days of an agile transition, IT development and operations teams have conflicting responsibilities. Agile software teams want flexibility; production IT requires stability. Agile teams want responsiveness and creativity; infrastructure teams seek efficiency and repeatability. Agile teams are cross-functional; infrastructure teams are typically specialized into functional server, data, and support silos. Each is prioritizing their own values and objectives responsibly, yet a clash is inevitable.

Consider these naturally opposing agendas and then amplify them across the entire organization to get a picture of the complexity of agile transformation. My emphasis on these political, cultural, and human complexities, rather than the techniques of scrum or XP, is based on one thing: experience. In every agile engagement I’ve undertaken, the basic methodology could be easily taught and practiced. The difficulty was in the discovery of the hidden web of personalities, alliances, duels, histories, and biases of the groups and individuals. Developing a strategy to evolve a resistant, fearful, change-worn firm into an agile enterprise requires deep understanding of both the overarching processes and practices that are out in the open, and the unspoken social structures that really influence behavior. It also requires empathy. Team members aren’t resisting agile to be ornery, or to test you (most of the time). They are driven by the norms, fears, and insecurities of organizational life.

We’ve all heard of the “people, processes , systems” approach to thinking about organizations. While this is a useful high-level frame for thinking about the enterprise, it has a few flaws. Each of these areas can expand into a universe of subtopics. The “people” element, for example, encompasses most of the cultural, political, and personality issues we’ve discussed. Firms spend months on process mapping, often discovering that they don’t really know how work flows, don’t understand or follow their own guidelines, and the existing processes don’t work. As IT becomes a strategic differentiator, the systems element of this model soars in complexity and importance. This is a functional view of the enterprise, but it doesn’t reveal many of the things an agile consultant needs to know.

“People, processes, systems” has exploded into dozens of theories of organizational structure. Rummler and Brache, in their classic Improving Performance 6 refined this into “Organization, Process, and Job/ Performer,” and applied a systems-thinking approach to the study of the organization. They offered a consultative, sober approach to reengineering, contrary to many of the radical, rip-it-out Business Process Reengineering (BPR) philosophies of that moment. Improving Performance was the mature refinement of an anarchic BPR movement that fed on its own radical ideas to become extreme and counterproductive.

In response to the criticisms of BPR , Schneider7 proposed an organizational view much esteemed in the agile community. In his segregation of organizations into four key cultural types

Control

Collaboration

Competence

Cooperation

Schneider moved away from the systems view and toward a humanistic view. Cultures arise because the participants seek certain ideals and outcomes, and cultures evolve based on human traits, values, and decisions.

He compares the Controlculture to a military organization. In a Control culture, “the individual motivation . . . lies in people’s need for power. The leadership of a control organization values dominance most. Control cultures are prone towards territoriality. Control cultures manage performance by imparting rewards and sanctions. They also quickly suppress discontent or any signs of disruption. People are reluctant to give bosses bad news . . . leaders get told only what they want to hear. Subordinates feel compelled to comply and stick to business.”8

In the Collaboration culture , values are aligned around people-driven, organic, informal participation, like a family or team, in which “little happens that is solitary or solely independent. Harmony and cooperation are essential elements . . . the process is inherently win-win. This culture puts more trust in people than any of the others…the collaboration culture must be more adaptive, ready and able to make adjustments than the other three cultures. The organization moves ahead through the collective experience of people from inside and outside the organization.”9

The Competence culture is based, in Schneider’s view, on the academic model, in which the things that are valued are “imagined alternatives, creative options, and theoretical concepts. Its decision making process is analytical, scientific and prescriptive. Life in a competence culture is intense and high-strung. The work is rigorous and carries a sense of urgency. The norms are excellence, superiority and challenge.” This culture “has competition at its center . . . this is a win-lose culture in which discord is present and less competent people fail. An organization whose goal is to create one-of-a-kind products . . . instinctively fills the organization with one-of-a-kind people.”10

The Cultivation culture , modeled after a religious or social enterprise, “pays attention to potential, ideals and beliefs, aspirations and creative options.” With a “focus on cultivating growth and development among their people. They strive to help people fulfill their potential . . . the culture is value-centered. Values and the value of people hold sway. Self-expression is highly encouraged.”11

It’s important to recognize that there’s no judgment in the Schneider model. No culture is deemed better than the others. Each has different values and intentions, but all are useful, depending on the product, the team, and the customer. In fact, most organizations have some elements of each culture. A pharmaceutical firm, for example, could have a Competence culture in the research and development (R&D) laboratories, while exhibiting a Collaborative culture in the marketing team. Schneider is talking about the dominant culture, the culture that fits the criteria of “the personality of the organization.”

The agile community has reacted to the rediscovery of Schneider’s ideas with a robust debate over how agile consultants should apply this information. In a survey12 performed by Michael Spayd of Collective Edge Coaching, agilists expressed a strong cultural preference for the Collaborative culture (47%) as an ideal for the agile team, with a Cultivation culture a strong second at 41%. With Competence at 9% and Control a tiny 3%, it’s pretty clear that agilists value the interaction, team ownership, and self-organization that are epitomized by the Collaborative, Cultivating cultures, and appreciate the cultivation of skills and human potential these cultures champion. It’s also obvious that the hierarchical, authoritarian model of Control, or the hypercompetitive, win-lose ethic of the Competition culture, holds little attraction for agilists.

This, however, is an exploration of the ideal, a situation consultants rarely encounter. In the real world, as noted, agile consultants will encounter Control cultures that nonetheless want to benefit from some agile practices, and Competence cultures that believe agility can enhance their competitiveness and drive to results. As noted, in most instances consultants will encounter mixed cultural environments where different teams or “silos” have adopted different values. Can agile consultants simply write off any of these cultures as incompatible?

For the agile consultant, there is no judgment, only observation and diagnosis. Armed with this information about the types of cultures we are likely to encounter, our job is to determine the best route to the level of agility that each unique enterprise can achieve. The practices of scrum are a great fit when you walk into an existing Collaboration or Cultivation culture but will challenge the most experienced consultant in a Control environment.

In Control organizations, many agilists recommend beginning their agile journey with Kanban. Kanban, the systematic work-flow approach that enables teams to explicitly limit their work in progress to ensure low inventory and a just-in-time value chain, might be a better cultural jumping-off point. While embodying agile principles, Kanban’s focus is not on the collaborative, iterative, team mentality, or self-directed teams—it’s about the process-driven flow of work through a production process. It doesn’t require organizations to rethink their Control-Based philosophies (at least at the beginning), or to grapple with foreign ideas like self-organization. As such, it seems a good fit for an opening foray into agile ideas for a Control culture .

The software craftsmanship movement, complete with its own manifesto,13 is a reaction to the concern by coders that all the attention on agility and speed-to-value risks putting them in the position of writing bad code. Scrum, the dominant agile method, provides a process that promotes iterative, collaborative development, but it doesn’t guide coders in the application of their craft. While quality and standards are explicit agile principles, their definition is up to the team and the product owner. The Software Craftsmanship Manifesto goes beyond the delivery of “working software” to the mandate for “well-crafted software” that “steadily adds value.” This movement has strong affinity with a Competence culture, complete with the competitiveness that we often see in academic or scientific communities. Because agile values are more humanistic than a typical cutthroat competitive culture, I expect the software craftsmanship movement to be more collaborative than a strict Competence culture. When encountering a Competence culture, agile consultants can use the software craftsmanship model to promote a commitment to excellence that suits the prevailing values.

Whatever culture you encounter, there are simple techniques for easing the agile transition. In my career I’ve adapted to “the way things are done around here” by applying an inside-outside perspective. Inside the agile team structure, we’re applying all the methods and practices, and measuring our progress, based on the agile approach we’re following. Outside, to the existing structure, we’re supplying some of the artifacts they expect to see, like project plans and status reports. Clearly a compromise with agile standards, these “adapters” enable us to begin the conversation about the difference between what they’re used to seeing and what agile provides. The migration from a Gantt chart to a burn-down chart is not momentous, but a transition period with some coaching on the benefits of agile can make it smoother. Reminding the Project Management Office (PMO) of the stack of unread status reports that inevitably pile up on their desk, versus the daily interaction of the stand-up, can be an opportunity to embody the “individuals and interactions” value of the Manifesto.

Strategic Goals of Agility

PWC, the consulting entity of IBM, recently published “Agility Is Within Reach,”14 in which it defines two goals that all enterprises seeking agility should focus on, strategic responsivenessand organizational flexibility. This focus on two key elements of agility summarizes nicely the goal we should be aiming for as agile consultants. The purpose of our engagement is not to immediately change their culture, or teach them agile concepts, or create a more humanistic environment. Those may be outcomes of the agile transformation, but the strategic goal of agility is competitive advantage and enhanced business results. Agile consultants, as opposed to scrummasters or team coaches, should focus on the strategic, measurable business results that agile offers the whole enterprise. The holistic, enterprise view of agile is ambitious, and may be too much for many firms, but the strategic outlook is what differentiates superior agile advisors.

The art of the consultant is to observe, diagnose, and then plan for the best outcome under prevailing circumstances. The likelihood of us changing a Control culture to a Collaborative one, at least in the short term, is slim. What we can do is diagnose the cultural proclivities of the enterprise and thoughtfully strategize on the best mix of agile philosophy, culture, and methods that will enable this particular enterprise, within this unique culture, to begin its individual agile journey. Not every enterprise has the will, or the desire, to evolve completely to enterprise agility. Most will make changes at the team level, and measure the impact of those changes, long before they commit to changing their core beliefs and practices across the organization. Part of the agile consultant’s art is to help customers figure out where on the spectrum of agility, from scrum practice at the team level to enterprise-wide evolution, they’ll get the most strategic advantage with the least pain and disruption. As agile proponents and believers, we may want every organization to transform completely to these ideals we treasure. When we take our personal objectives and emotions out of the equation, our responsibility is to take a sober inventory of the customer organization’s current state, strategically, culturally, and operationally, and help the customer develop an agile roadmap that fits its will and desire to transform.

Is 20th-Century Corporate Culture Obsolete?

Alfred P. Sloan, president, chairman, and CEO of General Motors Corporation from the 1920s through the 1950s, is often regarded as the author of the hierarchical, departmentalized, top-down management style that typified American business during those years. This style was immensely successful at building the giant American corporations we all know. After World War II, despite an abrupt decline in government spending, the U.S. economy boomed. One of the greatest periods of economic expansion and consumer spending in history resulted, in part, from the efficiencies designed into Sloan’s management style, where orders flowed from the top and compliance flowed from below, with no such thing as a “stakeholder,” just a shareholder. The success of America’s industrial war effort validated the autocratic, assembly-line, interchangeable worker mentality that characterized American manufacturing.

In the intervening years, however, Sloan’s command-and-control business philosophy has been severely criticized. James O’Toole,15 in analyzing Sloan’s management philosophy, noted that

. . . not once does Sloan make reference to any other values. Freedom, equality, humanism, stability, community, tradition, religion, patriotism, family, love, virtue, nature—all are ignored. His language is as calculating as that of the engineer-of-old working with calipers and slide rules: economizing, utility, facts, objectivity, systems, rationality, maximizing—that is the stuff of his vocabulary. 16

Yet even Sloan, the champion of hierarchical management, knew that technology, markets, and consumer tastes would inevitably change. In his classic “My Years With General Motors,”17 Sloan remarked that

The circumstances of the ever-changing market and ever-changing product are capable of breaking any business organization if that organization is unprepared for change—indeed, in my opinion, if it has not provided procedures for anticipating change. p. 508

Decades later, Sloan has been proven right on that count. The disruption, by new Internet entrants, of everything from the corner book store to the taxicab industry, and from the garage sale to the real estate market, illustrates his point. The success of those companies like Google and Facebook that have abandoned the traditional, hierarchical model of management and embraced a collaborative, experimental culture confirms the obsolescence of the hierarchical Sloan model, at least for “new economy” firms.

The surprising thing is that these command-and-control managerial theories are still in wide application. They seem so obviously unsuited to the modern business climate that their survival is clearly cultural and historical rather than pragmatic. When I started at Citicorp, it was described to me by a colleague as “the world’s largest paramilitary organization.” Warren Buffet believes that we only know who’s swimming naked when the tide goes out, and, during the financial crisis of the last decade, it was pretty clear that Citicorp and many other global financial institutions were skinny-dipping. Even in the staid financial industry, the top-down autocratic model I experienced at Citicorp couldn’t manage the experimental, opportunistic tactics of floor traders.

Agile Disrupts Everything

We know what makes agile popular among developers. Working as a team, they focus together on an achievable and valuable goal, improving their skills and the customer’s satisfaction with every iteration. Well-running agile teams work in an atmosphere of self-motivation, mutual respect, openness, and accomplishment. What’s not to like for them? But what is it that’s driving executives and managers to take agile seriously as a potential revolution in enterprise management?

In the executive suite, agility, like Total Quality Management (TQM) and BPR before it, is reaching its maximum hype cycle. From Harvard Business Review to The Huffington Post, the idea of scaling agile within IT, and then across the entire enterprise, is widely discussed and debated. Now that agile has proven itself in software, everyone else, from product development to marketing and operations, wants in. Executives want to see if they can get away from their fantasy18 strategic plans,’ with dozens, sometimes hundreds, of projects that will never get funded or executed, and replace them with iterative, incremental planning techniques that actually arrive at consensus and deliver value.

Let’s examine the economic forces that are driving business thinkers to consider agile as their next candidate for modernizing a faltering business model. There are, in my view, four strategic themes that are setting off light bulbs for academics and executives worldwide.

The biggest fear, of course, is digital disruption. In the early days of the Internet we used to say that nobody wanted to get “Amazoned”; now that services are also being disrupted, nobody wants to get “Uber-ed.” In either case, every business owner knows that there’s a young entrepreneur lurking somewhere, dissecting their business model and trying to figure out how to automate it, put it in the cloud, and take their market. The software market has evolved from omnibus, all-in-one business products to an atomized world of apps, where every niche or microprocess has the attention of startups and investors. In this granular market, every existing business and process is a target.

The concern about digital disruption is so widespread that respected management authors like Clay Christenson19 and Larry Downes20 have proposed making the evaluation and assessment of potential disruptors a strategic focus of every business. As Downes says in his Harvard Business Review article “Big-Bang Disruption ”:

You can’t see big-bang disruption coming. You can’t stop it. And it will be keeping executives in every industry in a cold sweat for a long time to come . . .

According to Christensen, even the business of consulting is vulnerable.

The same forces that disrupted so many businesses, from steel to publishing, are starting to reshape the world of consulting…undermining the position of longtime leaders and often causing the “flip” to a new basis of competition. The implications for firms and their clients are significant. 21

I was engaged by a smartphone manufacturing company to deliver training on Agile Project Management, and, as I got to know the students, one told a definitive story of disruption. Her team was building prototypes of new phones, and, in the middle of their project, Apple’s first iPhone was released. Prototypes just a few weeks from production were scrapped, and the design team did the proverbial “back to the drawing board” exercise. The innovative technologies built into the iPhone were far beyond anything they’d been prototyping, and they realized that day that their market had changed irrevocably. Which explains why they suddenly were anxious to begin a conversation about agile.

This is an example of digital disruption, but it also speaks to the exponential growth in the rate of change in technology. Product cycles compress tighter and tighter, queues form for the next version of a gadget immediately after its last release, and feature wars accelerate. Ray Kurzweil, well-known author and winner of the 1999 National Medal of Technology and Innovation, says of accelerating technical change:

An analysis of the history of technology shows that technological change is exponential, contrary to the common-sense “intuitive linear” view. So we won’t experience 100 years of progress in the 21st century—it will be more like 20,000 years of progress (at today's rate). Within a few decades, machine intelligence will surpass human intelligence, leading to technological change so rapid and profound it represents a rupture in the fabric of human history. The implications include the merger of biological and nonbiological intelligence, immortal software-based humans, and ultra-high levels of intelligence that expand outward in the universe at the speed of light. 22

While most businesses aren’t yet concerned about “software-based humans,” they do understand that technological change threatens their business models, their current products, and even their R&D function. How can you research and plan a product when, like the smartphone I described above, your prototypes may already be obsolete?

Another key factor that explains the hype surrounding agile is price and product transparency, or the death of unequal information. Before the Internet, the auto dealer had much more information about the price, lease structure, profit margin, and options than the customer. The insurance salesman knew much more about the likelihood of your accidental death. The for-profit school had private information about its success rate, as did the hospital. That unequal information gave the seller a decisive advantage. Those days of information inequality are gone, thanks to the Internet.

As in the stock markets, price discovery and product information are now transparent to the customer. Every car buyer goes to TrueCar or its competitors to learn about the car he is considering, read reviews, and check invoice and local pricing. The graduation and job-entry rates of for-profit schools are now widely available, as is the hospital’s mortality rate. I can go to eBay and, in an instant, learn the going price for a guitar, a table, or a pair of vintage earrings. Amazon reviewers will tell me which books to stay away from. So much data is being generated that many “big data” firms are springing up just to help businesses sort, categorize, and capitalize on these momentous data flows.

This transparency, of course , is the perfect catalyst for agility. Companies that can use this flow of data to understand the needs and desires of their marketplace, and make small, incremental changes to products in order to be responsive, have a deep competitive advantage. In fact, responsiveness to customer needs has overtaken sheer efficiency as a market differentiator. The Samsungs and Apples of the world, whose entire value chain can be redirected for every new product, use their agility to keep other players off balance. Amazon can, and does, incrementally change both the business model and the customer experience. These aren’t the low-cost producers, a sign of efficiency. They are the responsive producers, using data flow analytics and customer intimacy to quickly give the market what it wants. While Steve Jobs may have been right in his particular niche when he said that “people don’t know what they want until you show it to them,” for those businesspeople who are not Steve Jobs, data-driven responsiveness, not intuition, makes the competitive difference.

As Michael Treacy and Fred Wiersema, authors of a mid-1990s best-selling book,23 explained, there are three key strategies for any business: operational excellence, product leadership, and customer intimacy. Operational excellence, of course, refers to the efficiency that Alfred Sloan valued, while product leadership refers to the Apples, Teslas, and Gilead Sciences of the world, who can command premium prices for their innovative and superior offerings. These strategies have remained pretty much the same, though achieved through technological capabilities that were unavailable until now.

Customer intimacy, however, has changed completely. When Treacy and Wiersema published, they described customer intimacy as “the extraordinary level of service, guidance, expertise, and hand-holding” that companies provided. Their idea of customer intimacy was based on building multiple individual relationships with customers through great customer service, outstanding support, and the human touch that cements relationships.

In the time of big data, however, customer intimacy is based on the streams of data that both individuals and groups throw off, transaction by transaction. Amazon has no personal relationship with me, but it has intimate knowledge about my reading and shopping habits, my demographics, and my likelihood to respond to a product or promotion. Facebook doesn’t know me, but it sure knows about me; who my friends are, what posts I favor, my politics, religion, and marital status. From Facebook and Amazon to Google and Twitter, personal information is currency, driving ad revenue and product sales. So is the collective information, captured from millions of transactions and analyzed by sophisticated algorithms, which enables Netflix to make recommendations to individual subscribers.

When Land’s End, for instance, was a catalog company, its ability to collect data was limited to individual transactions from anonymous customers. All Land’s End usually saw was an order form and a check. Now, on the Web, It can trace every click, every purchase, and all the demographics of every customer, even those who are just browsing. The web world of customer intimacy may be intrusive and invasive in some people’s eyes, but, in most cases, customers are volunteering this data gladly to gain the benefits of the technology .

In the 1950s, during GM’s heyday, the industrial mantras of efficiencies of scale, interchangeable parts and workers, and long production runs on standardized models created the industrial giants. Many of these corporate behemoths, including GM itself, have faltered in the new economy. The threats of digital disruption, exponential technology advances, price and product transparency, and collective customer intimacy have changed the game completely. For many executives and management theorists, agile across the enterprise seems like it might be the solution to these threats.

Summary

Agility is about much more than methodology; in fact, a methodological approach to agile adoption is a key indicator of failure. Agile disrupts business models, culture, hierarchies, and operations. Studies have shown convincingly that, in order to evolve to agility, organizations need to address change from the team level up to the executive suite. Legacy cultural and managerial ideas and styles are cited as the key barriers to agility, and consultants need to assess the culture, history, business model, and managerial style in order to adapt their approach to the reality at hand.

The standard top-down, hierarchical corporate culture is showing its age, as modern workers reject the command style of management and expect input and creative freedom. We’ve surveyed many cultural styles, and discussed how an agile advisor can apply the right style to the existing culture.

Change is not an option. We’ve illustrated that the basics of every business model, from customer intimacy to product cycle time, have been changed by new customer expectations and disruptive technologies. Businesses that fail to keep up with these changes are in mortal danger. From price transparency to exponential increases in technical innovation, the forces of disruption require enterprises to rethink the traditional way of doing business and adopt new, more responsive and agile models. William E. Schneider, The Reengineering Alternative: A Plan for Making Your Current Culture Work by William E. Schneider (Richard D. Irwin, 1994)

Footnotes

2 Ibid.

3 William E. Schneider, The Reengineering Alternative: A Plan for Making Your Current Culture Work by William E. Schneider (Richard D. Irwin, 1994).

4 Edgar Schien, Organizational Culture and Leadership, Fourth Edition (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010), www.tnellen.com/ted/tc/schein.html .

5 www-01.ibm.com/common/ssi/cgi-bin/ssialias?subtype=XB&infotype=PM&appname=GBSE_GB_TI_USEN&htmlfid=GBE03297USEN&attachment=GBE03297USEN.PDF.

6 Geary A. Rummler & Alan P. Brache, Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space in the Organization Chart (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995).

7 William E. Schneider, The Reengineering Alternative: A Plan for Making Your Current Culture Work (Richard D. Irwin, 1994).

8 Ibid. at 28–29.

9 Ibid. at 44–59.

10 Ibid. at 63–77.

11 Ibid. at 81–98.

15 James O’Toole, Leading Change: Overcoming the Ideology of Comfort and the Tyranny of Custom (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995).

16 Ibid. at 174.

17 Alfred P. Sloan, My Years With General Motors (New York: Doubleday, 1963), p. 504, https://hbr.org/2014/03/my-years-with-general-motors-fifty-years-on .

18 https://hbr.org/webinar/2015/05/bring-agile-planning-to-the-whole-organization ; www.huffingtonpost.com/great-work-cultures/scaling-agile-to-create-a_b_7537818.html.

23 Michael Treacy and Fred Wiersema, The Discipline of Market Leaders: Choose Your Customers, Narrow Your Focus, Dominate Your Market (Perseus Books, 1995).