Is there an agile personality type? Is agile evolution destined to succeed or fail based on the personalities of the executive team and the culture of the organization? Are Industrial Age companies, like Ford or Proctor & Gamble, with their history of hierarchical management styles, doomed to fail at agile? Agile consultants must consider these and many other questions before they embark on the mutual effort to enhance agility and responsiveness.

Explore the Environment

Before we tackle these questions, let’s discuss why they matter. If there is a recognizable type of personality that is more or less likely to engage successfully in agile evolution, as agile advisors we should be prepared to identify those types, and adapt our training and consulting to the personalities we’re confronted with. If an executive asks us in to discuss agile adoption, it would be helpful to be able to put his, and his team’s, personalities on some type of spectrum that might give us guidance for the voyage ahead. If some particular types of cultures are inherently prone to fail at agility , should we steer clear of them, or take on the challenge to help them adapt? I raise these points because many agile advisors , acting at the “accidental” level of engagement that Michael Sahota describes, walk into every engagement with the same tools, methods, and practices, as if there’s a single roadmap to agility and these cultural and personality issues are immaterial.

The question of agile personality types has actually been widely studied. From the academic studies1 done at Goethe University in Germany, to the anecdotal analysis performed by Mario Moreira2 for The Agile Journal, the idea that there are specific personality types that are suited for agile has been analyzed both formally and informally. Even Mike Cohn has gotten into the conversation, with a post3 on different types of resistors that agile change agents might find in organizations.

As illustrated in Figure 4-1, Cohn’s analysis isn’t specifically about distinct personalities but more about the attitudes that some resistant individuals might bring to the agile evolution process. He divides the resistance camp into four quadrants:

Skeptics

Followers

Saboteurs

Diehards

Figure 4-1. Mike Cohn’s resistor spectrum

He contends that team members adopt these positions based on two criteria, their desire to either sustain the status quo or oppose agile methods and their passivity or activeness. Skeptics both dislike agile and are passive participants , while Diehards are invested in current processes and are actively resisting change. Here’s Cohn’s diagram, from the cited post, illustrating his theory:

Cohn’s experience-based analysis is important, but it only addresses resistors. Moreira digs a bit deeper. Though not a rigorous study, it raises some interesting ideas about the sorts of team members we might encounter. He categorizes these personalities as follows:

Innovator

Champion

Workhorse

Bandwagon

Cowboy

Deceiver

Denier

From the Denier , who actively disputes agile theories but typically has little experience with agile concepts, to the Innovator , who provides agile leadership from within and has deep experience in agile culture, this continuum is quite useful for understanding and handling the objections, resistance, and impediments that an agile change agent will encounter, especially as agile spreads beyond information technology (IT) . The Denier plays an important role in agile evolution , enabling agile consultants to confront head-on the myths and misconceptions that many first-time agile participants may be carrying. The Cowboy confirms the worst mythology about agile, using it as an excuse to jettison all discipline and make it up as he goes along. The titles Moreira has assigned are self-evident to any experienced change agent, agile or not.

On the academic side. the research4 performed by the team at Goethe University in Frankfurt takes a more formal approach to the question, using familiar personality models like Meyers-Briggs 5 and the Five Factor Model (FFM) 6 to understand how different personality factors might influence the acceptance and competence of individuals in an agile team. Through a series of interviews with agile team members, they evaluated individuals against the FFM personality traits and analyzed these traits against their attitudes and effectiveness in agile settings. The five traits in the FFM model are:

Extraversion

Agreeableness

Conscientiousness

Neuroticism

Openness

They found that Agreeableness is a key factor for developer success with agile, while Conscientiousness is a key trait for scrummasters. The research goes into considerable depth about the individual traits that apply under these five broad categories, which I won’t reproduce here.

The point is that the personality traits of individuals, from the executive sponsor to the individual developer, have a significant influence on the ability to adopt agile techniques. While I scoff at the study’s recommendation that every agile team should undergo testing to uncover these attributes, I believe that the agile consultant who understands these personality elements, and is on the lookout for them when she engages, is less likely to apply a one-size-fits-all approach , and will instead design and implement a strategy that fits the team.

The clues are all around us when we start to engage. Is the sponsor genial and welcoming or austere and formal? Does the sponsor take his time to describe the scenario, or is he rushed and harried, answering the phone continuously while we chat? Is she enthusiastic, or does she seem to be responding to an edict from above or pressure from below? Is the client in immediate crisis and clutching at straws, or applying a reasoned, strategic approach to enterprise agility? Experienced consultants will spend as much energy evaluating the personalities as they do understanding the client’s scenario. When I engage with a new client, I‘m observing the demeanor, the physical setting, and the client’s attitude as methodically as I am the potential engagement.

Remember also that clients, especially at the sponsor level, are considering agile for strategic reasons, and that it’s our job as advisors to consider the strategic as well as the tactical objectives. As I’ve noted before, I still encounter many coaches who can recite the Manifesto and principles verbatim but never have a strategic, value chain, or process conversation with their sponsor (except as it exclusively relates to software development). At the enterprise level, this can’t succeed. If we don’t understand how clients make money, how they compete, how they deal with customer feedback, or what processes they follow to achieve their outcomes, how can we know if we’re addressing the right improvement opportunities?

When it comes to assessing the personality traits of a potential client, I believe that consultants must evaluate the potential for success, and make engagement decisions based not on their need to pay the bills but on the probability that the engagement can succeed. If the potential client enterprise doesn’t understand what it is asking, can’t articulate a strategy or a set of success criteria, or simply is someone you don’t think you can advise successfully, it’s your professional responsibility to decline the engagement. Just as an ethical judge will recuse himself from a case he can’t judge impartially, ethical consultants will consider the likelihood of a successful outcome and recuse themselves from doomed engagements.

Mapping the Value Chain

During this exploration process , it’s not just the client personalities we need to discover; we also need to dig into processes and value chains. When I engage in a change project, agile or otherwise, I often engage an experienced process mapping partner to help walk through both the value chain and the individual processes that produce the outcomes desired. My particular partner of choice is ProcessTriage ,7 a local (Kansas City) firm that specializes in both value chain and process mapping and improvement. The specific firm you choose is not the point: evaluating the value chain, and the processes that go into creating value, is a fundamental element of guiding the client to agility. We’ll explore the concept of value chain here, but it’s not my intention to give a full tutorial; there are many other sources for that, from Michael Porter’s book,8 where the idea originated, to multiple web pages9 that provide insight into the usage of value chain, or value stream, analysis.

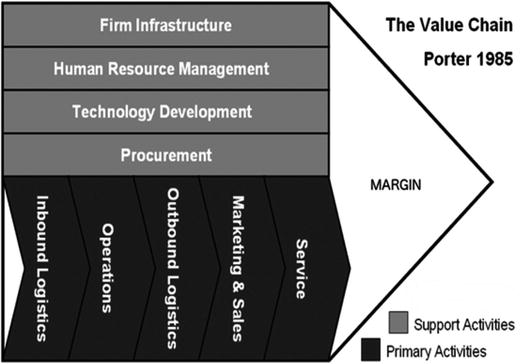

Let’s first look back to Porter’s original idea, from his 1985 book. We’ll start with a couple of definitions, and a graphic (Figure 4-2) depicting Porter’s conception of a value chain, and then we’ll dig into the details :

Value chainrepresents the internal activities a firm engages in when transforming inputs into outputs.

Value chain analysis (VCA)is a process where a firm identifies its primary and support activities that add value to its final product, and then analyzes these activities to reduce costs or increase differentiation.

Figure 4-2. The value chain

The idea is a simple one, although performing the analysis is not. Enterprises have inputs and outputs, and they create competitive advantage and profits based on the value they can add to their inputs. According to Porter, firms can create competitive advantage two ways: through lower cost or through differentiating features. As illustrated in Figure 4-2 in the “Primary Activities” section, the firm receives inputs (e.g., raw materials in an automotive business, or intellectual property on a content-based web site), transforms these inputs by performing some operation on them, creates a mechanism for distributing the end product, identifies customers and their needs to create demand for the product, and provides services to customers as they use the product to gain value .

Enterprises also have a set of “Support Activities” as shown in the figure, such as IT, HR, procurement, and infrastructure, which includes elements like the physical plant or office, the organizational structure, and the firm’s culture. The tip of the arrow, in Figure 4-2, represents the margin that firms can achieve when their sales are greater than their costs. When a firm can perform these activities efficiently and effectively it can achieve superior margins and competitive advantage.

For businesses that primarily rely on cost advantage, like Wal-Mart , their analysis of the value chain will focus on removing costs from any, or all, of the value chain activities. They seek to identify economies of scale, high utilization, and efficient linkages within the chain. Those that focus primarily on differentiating features, like Google , concentrate on innovation, uniqueness, and continual responsiveness. This is not to say that firms concentrate solely on one or the other. Manufacturing firms like Ford Motor Company attempt to excel in both categories, and web-based businesses like LinkedIn , while focusing on a unique niche and innovative features, must also maintain low costs to achieve margin.

I don’t mean to imply that, in the exploration phase, I’m going to drag a process expert into the initial sales meeting and start drawing diagrams; that piece comes later. I’m emphasizing here the agile consultant’s responsibility to start thinking strategically about the client’s value chain from the outset. This is, again, where the consultant’s powers of observation are critical. As we begin to understand the client’s business, culture, and structure, we should start creating a mental model of the business, with Porter’s value chain ideas as a foundation, so we can start to identify improvement opportunities. When we think about an enterprise holistically, it becomes obvious that, while improvement in the software development process , for example, may optimize a tiny element of the entire value chain, the progressive optimization of surrounding elements, and their support structures, is where the real impact lies. Agile advisors must make the distinction between “suboptimization ,” or the optimization of one local element, and holistic optimization , in which we’re looking at the linkages, interactions, and effects of change across the entire chain, and targeting our efforts at the right improvement opportunities for this unique client. As I noted, this is a brief fly-by of VCA , and there are many great references to help you dig deeper.

Explore the Incentives

In many firms, the climate is competitive, hostile, and judgmental. Team members are evaluated quarterly and, in many companies, are “stack-racked” against their peers, creating a combative, rather than a cooperative and collaborative, atmosphere. Some firms even have a forced “up or out” mentality, in which the bottom 10% of ranked employees is put on a performance plan, and “managed out” if they don’t improve their rankings. While some more enlightened firms will incorporate a “360 measurement” approach , in which teammates and other managers also get a chance to weigh in on the employee’s skills and accomplishments, those firms are in the minority.

Since these rankings determine pay, promotion, and prestige, they are important in terms of their effect on careers, attitudes, and atmosphere. The theory, based on Peter Drucker’s Management by Objectives (MBO) philosophy outlined in his 1954 book,10 claimed that MBO was the cure for military-style command-and-control management, by setting agreed objectives for each manager, team, and individual, thereby freeing managers to focus on strategic issues rather than task management. Drucker's original idea was that the MBO process would be a constructive dialog between managers and their team members, in which they would collaboratively determine realistic goals for the next period, whether quarterly, semiannually, or annually, and together build a sense of ownership, commitment, and improvement areas.

It hasn’t quite worked out that way. MBO works under the theory that objectives stay constant over the evaluation period, when in reality, especially in the agile, responsive enterprise, work is dynamic and objectives change frequently. There’s little space for creative activities that don’t fit into static objectives. Managers are typically the judges and juries in these organizations, and the externals, such as weak peer skills, broken processes, poor organizational communication, lack of vision, and lack of leadership are disregarded, as employees are instructed that it’s their responsibility to live with the culture that exists. The overall problem with MBO-based management is that it stifles creativity, creates a hostile and competitive environment, saddles team members with tactical goals that don’t have meaning to them, applies a reward-and-punishment system that is known to demotivate knowledge workers, and creates a “not in my objectives” atmosphere that values compliance over creativity. Although MBO was designed as an interactive exercise in which team members develop their own objectives and then iterate through them with their manager’s guidance, in most firms it has devolved into a mechanistic system in which those conversations never happen, team members are encouraged to take on objectives that they don’t believe and have no interest in, and managers are put in the uncomfortable position of force-fitting some team members into low ranks in order meet an arbitrary quota.

What gets measured gets managed is a common quote in executive ranks. That may be true, but, in agile terms, what doesn’t get measured and rewarded, like intrinsic motivation, creativity, team collaboration, and a focus on customer value, creates disincentives for the behaviors that the agile enterprise needs the most. We’ll discuss in later chapters the techniques that agile consultants can use to guide the changes organizations must make, from these type of measurements to metrics that encourage agility, responsiveness, and creativity. I give this overview here to again emphasize the observational powers of agile consultants. Guiding the enterprise to evolve its thinking, from these traditional, individual-focused, static measurements to the dynamic, team-based metrics that encourage collaboration and creative thinking, is an example of the heavy lifting that enterprise-level consultants must take on. Observing and thoughtfully considering them is the first step of the eventual education and persuasion that we’ll need later in the evolution process.

Engaging with Trust

Nothing happens without trust. From the auto mechanic to the doctor or accountant, if the expert can’t develop a sense of trust and confidence with the client, then relationship issues are likely to be a drag on current and future engagements, even if the service is exemplary. For the consultant coming in to help evolve the agile maturity of an enterprise, trust is even more critical. The client organization is taking a risk by inviting us into its house, introducing us to its colleagues, and exposing the organization’s challenges and flaws. If the consultant turns out to be incompetent or untrustworthy, all the agile knowledge in the world won’t save the engagement. Immature consultants, I’ve observed, sometimes make the assumption that being selected for an engagement means the client trusts them already. Big mistake. Trust is never granted, it’s always earned.

The development of trust is an uphill climb. With consultants, as with auto mechanics, the “trust curve” follows a typical path from transactional interactions to favored vendor status and then toward trusted advisor standing. I laugh when I see LinkedIn profiles in which the individual describes herself as a “trusted advisor.” Trusted by whom, and based on what? Like Abe Lincoln’s fifth leg,11 calling yourself a trusted advisor doesn’t make you one. The progression to trust requires consultants to display honesty, forthrightness, and clarity from the beginning. Our consultative skills and our personal demeanor are under constant evaluation with every team member we meet. Those are the qualities clients gauge long before they have an opportunity to assess our agile domain knowledge. From the initial meeting to the conclusion of the engagement, there’s only one way to earn trust, and that is to deserve it. Clients don’t hire consultants to tell them what they want to hear; they’re surrounded by that type of advisor all day, each typically pushing a personal agenda. They hire us to tell them those things that only an objective outsider can utter. Of course, they expect domain expertise, but it’s our ability to stand outside the culture, and to observe and report on the unproductive behaviors we see without the ego, emotion, and agenda of insiders, that clients value most.

When I think about consulting behaviors that work against trust , I think of the “eternal engagement” business model , in which consulting firms try to make themselves indispensable and embed themselves for life. I’m talking about the “inside spy” model I’ve mentioned previously, in which, in the name of scope expansion, consultants turn into eavesdroppers, searching for opportunities to expand their footprint. I’m talking about the notorious bait and switch model of the Big 5 firms, bringing in veterans for the sales process and then loading the engagement with green rookies. I’m talking about consultants who inflate their own knowledge and experience to get the gig, with the idea that they can learn as they go, on the client’s dime. I’m also talking about those consultants who still propose a big, upfront plan model, perpetuating the illusion that they can know, in advance, how a project will proceed and what obstacles they’ll encounter on the way. All of these behaviors doom the relationship to an adversarial, unproductive encounter, with unfulfilled expectations all around.

The customer-value focus that we preach within the agile principles also applies to the agile consultant. If we’re more concerned about our longevity in the engagement than on the client’s interests, we are behaving unprofessionally, and sabotaging or own credibility and trustworthiness. The instant our credibility, competence, or trustworthiness is questioned by the client or the client’s team, the engagement is on thin ice. Through my long experience as a consultant, I’ve learned one simple motto: tell the truth. If you don’t have a specific skill that the client expects, admit it. If you have concerns about the potential for success, state them. If the engagement is a stretch that you think you can conquer, say so. If you fear, from your exploration, that there are significant challenges that the enterprise will need to overcome, explain them, and describe your ideas for conquering them. Prospective clients appreciate honesty and self-knowledge above braggadocio and wishful thinking.

One error I often see consultants make is to assume that the client knows how to engage with an outside advisor. Even for large, established firms that frequently use outside advisors, I make it a point to clearly state the process I foresee, and both the client’s and the advisor’s role. How will we kick off the engagement? What homework might you have to do, and what background information do you expect the client to provide? At what cadence do you expect to engage? Who will be the Product Owner of this engagement from the client side, and what will the client’s role and commitment look like? What are you committing to do, and to what is the client committing? What are the expected deliverables? What is the expected outcome? What does success look like? To avoid misunderstandings and recriminations later, clarity of expectation and commitment is vital. In an ambiguous and incremental project like agile evolution , in which we can’t possible know the client’s desire, capacity, or commitment to change until we experience it, missed expectations are a constant danger, so answering these questions becomes imperative.

It’s imperative also that we are upfront about the risks and challenges of an agile transformation. Clients who have never undertaken a disruptive change program like agile evolution may believe that it’s merely a matter of training and coaching a couple of scrum teams. If that’s the ultimate goal, that’s fine, but if the client believes that doing so equals enterprise agility, you’re setting the engagement up for disappointment. On the other hand, clients that have already experienced an attempted agile migration that’s fallen on its face or “snapped back” to the prevailing culture will bring skepticism and doubt into the engagement. A candid conversation about obstacles we’ve experienced before, or failed adoptions that we’ve participated in turning around, can go a long way to counteract any negative perceptions. In short, a large part of building trust is based on building confidence in your abilities, and in your sincere belief in the ultimate success of the engagement.

When I interview any project manager, scrummaster, or consultant for a potential engagement, I ask him to describe his skill set, and then to prioritize those skills. The magic phrase I’m seeking is managing expectations. When the candidate can only articulate a set of technical skills or domain expertise and never mentions consulting skills or the ability to manage client expectations, my finger starts reaching for the eject button. The clarity of expectations, and the ability to help the client visualize a successful engagement and understand the boundaries of that engagement, separates the Subject Matter Experts from the consultants. Clients frequently have built fantasy castles, both in their own minds and across the enterprise, about the cost, schedule, and difficulty of achieving their agile goals. Consultants, especially in the agile realm, who have difficulty correcting false assumptions or reporting on adverse circumstances that might affect the project have a tough road ahead of them. Obstacles will inevitably arise, and bad news will inevitably need to be conveyed. Agile evolution , like agility itself, is reality-based, and reality is messy, unpredictable, and not subject to brute force or wishful thinking.

Framing the Engagement

When we have evaluated the personalities of the players and the potential for a successful engagement, thought about the enterprise value chain, taken a peek at the current performance-measurement and incentive practices, begun to build trust and confidence with the client, and articulated roles, commitments, and expectations, it’s time to start developing an agreement that documents those findings. As I’ve noted, the traditional big predictive plan approach is obsolete in project management, and is therefore inappropriate in agile engagements. In fact, agility emerges from the recognition that we can’t accurately predict and plan. Acknowledging this, let’s also acknowledge that the predictive, all-in plan is exactly what many sponsors are expecting. Educating the sponsor and guiding her away from that expectation falls to the consultant. For many clients, the acceptance that traditional project management techniques have failed is a component of their decision to embrace agility. Others are experimenting with agility, but still clinging to the traditional management techniques that reassure them with the illusion of control.

The first step to reaching agreement is to test your understanding of the client’s current state of agility, the client’s perceptions and expectations. So what I think you’re saying is . . . and help me understand how . . . are two of the most potent phrases in the consultant’s toolkit. Our goal is to come to agreement on what we’re there to do, what constitutes both a reasonable approach and a successful outcome for the sponsor, and who is committing to do what to further that goal.

Just as I scorn the big, upfront plan, I also reject the big, upfront consulting contract. “Customer collaboration over contract negotiation” is an important precept of agile theory , and I have much respect for the values that produced that principle. Equally important to me is the iterative nature of agile evolution. Unlike a data center project or the building of a bridge, we can’t know, or even approximate, the end at the beginning. When we enter an engagement with a new client, we have no visibility into the teams’ competence, will, or desire to adopt agile practices, and little insight into the culture and obstacles we’ll discover along the route. Our engagement documents must reflect that reality.

The agreement I visualize with the client looks much more like a letter of engagement than it does a formal contract. I’m agreeing that I’ll apply my agile domain knowledge, and my consultative skills, to help the client discover its own agile destiny, and my agreements reflect that fact. I’ll state explicitly: I’m engaging to assist and guide the client enterprise to their agile objectives, based on my experience and domain knowledge. I’ll acknowledge the client’s goals, but I’m not promising anything except to apply my best efforts to help the client reach its maximum agility within its boundaries. If the client responds that this is too “squishy” and ambiguous, I’ll remind him that that’s exactly what agile evolution entails. Just as in an agile development effort, I’m prepared to agree to a predefined time box and “cashbox,” and to commit to guiding the client to its organic limit of agility within those constraints, but there’s no circumstance in which I’ll commit to a fixed scope with a promised level of agility guaranteed at the end.

That’s often the rub. Clients that are experienced with “big bang” consulting contracts are often stuck in the perception that only a fixed-scope, fixed-fee, fixed-budget contract protects them from unfulfilled expectations. Traditional consultants are equally convinced that only a fixed-scope project protects them from dreaded scope creep. We’ll talk in depth in later chapters about the business model of an agile consultant, but my key point here is that many clients, especially those that have not internalized the agile mind-set, will struggle with the iterative approach to agile evolution. Nimble consultants will invest significant energy in building trust at the start, educating sponsors about the known successes of the iterative, incremental approach, and partner with the client to develop an engagement agreement that reassures the client without putting the consultant in an untenable position.

If we’re committing to a time box and cashbox, it’s urgent that the client enterprise is prepared to document its own obligations, and I’m not talking about fees. Participation, commitment, interaction, and a robust feedback loop are central elements of any agile project, and they are equally critical in an advisory relationship. Every experienced consultant , agile or not, has dealt with the client that makes all kinds of grandiose commitments to participate during the contract negotiations, only to disappear in a puff of smoke when it comes time to actually collaborate. There’s nothing we can do to drive agility without the client’s participation, enthusiasm, and desire. Even the simplest letter of agreement must spell out the consultant’s expectations for customer access, clear project ownership on the client side, and the roles and commitments of all key client players. Clients are frequently accustomed to the “throw it over the wall” style of consulting engagement , in which their involvement occurs at the beginning, to toss the specs across the desk, and at the end, to evaluate the consultant’s results. The burden is on the consultant to ensure that client participants understand and commit to their roles, and honor these commitments.

Summary

“A bad beginning makes a bad ending,” said Euripides back in 400 B.C., and that wisdom has not changed. The Explore and Engage phase of an agile engagement sets the stage for success or failure. Agile consultants who dive in to an agile evolution project, especially at the enterprise level, without respecting Euripides’s logic, defeat their own purpose. The consultant who disregards the unique circumstances of every enterprise, and brings out the same tools no matter the on-the-ground conditions, may have some success at the scrum-team level, but evolving out across the enterprise requires mature observation and consultative skills, and the ability to inspect the situation and adapt to the culture, competencies, style, and boundaries that reality imposes. If you’re operating, as an agile consultant, at the accidental level of skill, don’t be surprised when you crash.

On the positive side, agile consultants who engage thoughtfully, observantly, and intentionally, and meet the enterprise where it is, in order to guide it to where it wants to be, have an excellent chance of starting off on the front foot and achieving breakthrough results for the enterprise and teams they have the privilege to advise.

Footnotes

1 aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1015&context=ecis2015_cr.

2 cmforagile.blogspot.com/2011/04/knowing-your-agile-personalities.html.

4 Ruth Baumgart, Markus Hummel, and Roland Holten, “Personality Traits of Scrum Roles in Agile Software Development Teams—A Qualitative Analysis,” ECIS 2015 Completed Research Papers, Paper 16 (2015).

8 Michael Porter, Competitive Advantage (New York: Free Press, 1998).

9 www.netmba.com/strategy/value-chain/ is one example; there are many others.

10 Peter F. Drucker, The Practice of Management (New York: Harper Collins, 1954) (reissued April 20, 2010).

11 Abraham Lincoln is purported to have posed the riddle, “If you call a tail a leg, how many legs does a dog have?,” to which the answer was usually “five.” Lincoln’s response? “No, four . . . calling a tail a leg doesn’t make it one.”